#GiveCredit: the cultural appropriation of Otomi Embroidery

Over the weekend, Mexico’s Minister of Culture called out luxury American fashion label, Carolina Herrera, and its creative director Wes Gordon for appropriating indigenous embroidery and motifs in their 2020 resort collection.

In response, our co-founder and global operations director, Carry Somers, shared her view:

“Fashion has been a globalised industry for several centuries, both in terms of its supply chain and the diffusion of trends, and throughout that time the true cost of economic development has far too frequently been born by indigenous peoples whose natural resources, skills, knowledge and designs have been exploited to bring wealth to a few.

We now have the Nagoya Protocol relating to the fair and equitable sharing of benefits relating to traditional knowledge of biological resources, although this should be implemented far more extensively by fashion brands – currently used in just a few cases by luxury brands and mostly relating to perfume.

When will we see a similar protocol around the wider intellectual property of indigenous groups to help not just to separate inspiration from appropriation, but to give designers and brands a framework within which to operate with clear guidelines on benefit sharing where it is clear, as is the case with Wes Gordon’s new resort collection, that this goes beyond mere ‘inspiration’ in its use of Otomi embroidery designs from Tenango de Doria or floral embroidery from the Isthmus of Oaxaca. Intangible cultural heritage must be protected and fairly rewarded.”

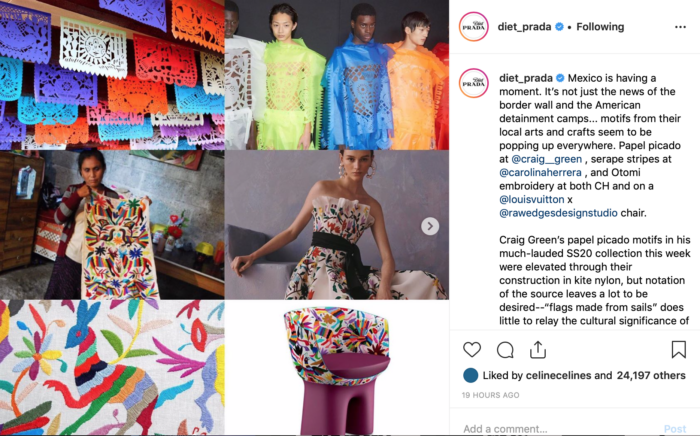

As this story develops, and we await a response to the Government of Mexico from the brand, we learned more from the Instagram account @givecredit_ which calls out cultural appropriation in the industry, and from the iconic copycat whistleblower, @diet_prada. Its latest post pointed out that Carolina Herrera is far from the first brand to ‘borrow’ ‘inspiration’ from Mexican culture in the design world, citing a Louis Vuitton collaboration with Raw Edges Design Studio, and designer Craig Green’s use of the Papel Picado Mexican folk art.

@diet_prada says, “Mexico is having a moment. It’s not just the news of the border wall and the American detainment camps… motifs from their local arts and crafts seem to be popping up everywhere… All these brands could take a page out of @hermes ‘ book. In 2011, the French luxury brand partnered with the Museo de Arte Popular in Mexico City to work with local artisans to reproduce the Otomi embroidery motifs as prints for their silk scarves. With a world of inspiration at the click of a button, designers and corporations need to exercise due diligence as their efforts can have a greater global impact than simply spurring fashion’s next trend.”

As a movement, we at Fashion Revolution do not typically single out brands, as we don’t see this as an effective method of generating system-wide change. Yet, it’s become increasingly apparent that this tendency towards cultural theft isn’t exclusive to a single designer or collection. As the revelations around copycat renditions of Otomi embroidery unfolded on Instagram, @GiveCredit_ even posted a beach towel from the United Colours of Benetton touting the description ‘designed in Italy’ below the product heading. This kind of name-dropping provenance, which paints a picture of high fashion mythology on factory-made goods is all too common on the high street, and it’s not exclusive to our clothes. The reason many of our phones are branded with the slogan, ‘designed in California’ follows the same logic, wiring us to view our mass-produced goods as exclusive, luxury products.

Yet this marketing strategy is exponentially more problematic when ‘designed in Italy’ isn’t just a marketing quip but an outright lie painted over the truth, ‘stolen from artisans in Mexico’s Altiplano region’. For Carolina Herrera, the brand follows in the same line with creative director Wes Gordon professing a credit-less but Instagrammable quote: “All the prints are designed in-house. It’s a labour of love”. We think not.

Whenever flags arise around the appropriateness of cultural borrowing in fashion, they are followed by debates around intellectual property rights and respect for artisanship. Yet, Carry Somers says that global artisans need legal protection similar to the Nagoya Protocol if we are to combat this aesthetic theft in a tangible way.

A few months ago, we published the 4th issue of our fanzine: FASHION CRAFT REVOLUTION, which chronicles the effects and underlying racism of cultural appropriation in fashion in pieces by Céline Semaan and Monica Bota-Moisin. The issue also looks at how respect for artisans and traditional craft can lift people up and develop strong ties to community, family, and history. If you haven’t already, you can purchase a copy of our zine here.

However you feel about cultural appropriation, and whichever side of the debate you fall under in this latest story of Carolina Herrera’s collection, we think it’s worth considering these golden words of Su’ad Abdul Khabeer, quoted by Céline Semaan in the zine, “You don’t need to be a voice for the voiceless, just pass the mic“.