Hungarian:

A tudatos fogyasztók új hullámával a fenntartható divat iránti kereslet virágzik és ha már erre az oldalra tévedtél, akkor biztos van bennünk valami közös. Lehet te is szenvedélyesen szereted a divat világát, vagy lelkesen próbálsz megragadni minden olyan alkalmat, amivel a saját mikrokörnyezetedben is olyan változást tudsz elérni, amivel egy picit könnyíthetsz a bolygó terhén.

A Fashion Revolution mozgalom tagjaként hiszünk a közösség erejében, egyéni szinten is lehet változást eredményezni!

Egy tanulmány szerint az Egyesült Államokban a vásárlók 59%-a szeretné, ha a divatipar fenntarthatóbbá és környezetbarátabbá válna. Bármely divatháznak, amely az élvonalban szeretne maradni, annak kapcsolódnia kell ehhez az irányvonalhoz, és meg kell felelnie avásárlók igényeinek. Ma már nem lehet szemet hunyni a textilipar által okozott környezetkárosodás felett. Mind a fogyasztók, mind az iparág egészében bekövetkezett változás miatt a fenntartható divatpiac értéke 2021 és 2025 között várhatóan több mint 3 milliárd dollárra nő.

A jó hír az, hogy rengeteg olyan lépés van, amivel a fenntartható divat ösvényén olyan játszi könnyedséggel lépdelhetsz, mint Carrie Bradshaw az Upper East Side utcáin. Ez a lista útravalónak szolgálhat, miközben tudatosabb vásárlási szokásokat alakíthatsz ki.

Secondhand

Turkálóba, vintage üzletekbe vagy gardróbvásárra járni, olyan, mint egy kincskeresés, sosem tudhatod mi akad majd a kezedbe. Az adott darab történetet mondd el szavak nélkül. A használt ruha piac egyre nagyobb teret hódít, de nem is csoda, hiszen ezek a darabok karaktert és egyediséget adnak a gardróbunkhoz, miközben új életet adunk a mások által már megunt ruhadaraboknak.

Upcycling

Az upcycling, más néven értéknövelő újrahasznosítás, az ökotudatos fogyasztók kreatív oldalát hozza elő. Izgalmas alkotói folyamat, amikor az eldobott rongyokból valami teljesen új születik, farmerből táska vagy régi nyakkendőkből szoknya. Rengeteg lehetőség rejlik ebben a technikában, így érdemes szabadjára engedni a fantáziánkat.

Körforgásos divat

2025-ben is az egyik legdominánsabb trendek közé tartozik a körforgásos divat. Ez egy olyan üzleti modell, amely a hulladék csökkentésére, valamint az erőforrások újrafelhasználására és újrahasznosítására összpontosít. A cél az, hogy már a tervezés folyamat során gondoljunk arra, hogy mi lesz a ruhák sorsa életciklusuk végén, miként lehet őket majd újrahasznosítani. Izgalmas innováció zajlik a textiliparban a biológiailag lebomló vagy komposztálható szálak előállítása terén. Az egyik ilyen újítás a CELYS komposztálható szál, amely 179 nap alatt természetes módon szén-dioxiddá, vízzé és biomasszává bomlik le. Már a boltok polcain is találkozhatsz olyan termékekkel, amelyek 100% újrahasznosított anyagból készülnek, vásárlás előtt minden esetben érdemes elolvasni a ruhák címkéjét.

Etikusság és átláthatóság

Az etikus beszerzés azt jelenti, hogy az anyagok beszerzése során nem okoztak kárt sem az embereknek, sem a bolygónak, valamint a gazdálkodás, a termelés és a forgalmazás során érvényesítették a tisztességes kereskedelmi gyakorlatokat. 2025-ben a márkáknak átláthatóbbnak kell lenniük gyakorlatukkal kapcsolatban, és fenntartható állításaikat tanúsítványok vagy harmadik fél által végzett ellenőrzések formájában kell alátámasztaniuk.

Minimalista divat

A fenntartható divatmárkák egyre inkább a minimalista esztétikát alkalmazzák, hogy felszámolják a gyakori szezonális vásárlások szükségességét. Ez az irányzat legkönyebben az egyik kedvenc mondásunkkal írható le; „a kevesebb több”. A trend fő jellemzői a letisztult vonalak, semleges színek és időtlen dizájnok. A hangsúly a minőségen van, nem pedig a mennyiségen. Sok esetben bele sem gondolunk, hogy egy-egy darabot többféleképpen is fel tudunk venni, csak a megfelelő párosításra van szükség. Az eszközeink tárháza végtelen, csak a képzelet szabhat határt.

Remélem sikerült ráébreszteni arra, hogy a fenntartató divat, nem is olyan idegen és unalmas terep, mint ahogy azt elsőre gondolná az ember. Válaszd ki számodra a legjárhatóbb utat és alkalmazz Te is zöldebb gyakorlatokat!

Írta: Arnóth Nikolett, Fashion Revolution Hungary

Forrás: https://www.celys.com.au/blog/sustainable-fashion-trends-for-2025-what-to-expect

Képek forrása: https://www.pexels.com/hu-hu/

English:

With a new wave of conscious consumers, the demand for sustainable fashion is booming, and if you’ve landed on this page, then we have something in common. You may be passionate about fashion, or you may be eager to seize every opportunity to make a difference in your own micro-environment and help the planet.

As a member of the Fashion Revolution movement, we believe in the power of community, and we can make a difference on an individual level!

According to a study, 59% of consumers in the United States want the fashion industry to become more sustainable and environmentally friendly. Any fashion house that wants to stay ahead of the curve must connect with this trend and meet the needs of its shoppers. Today, we can no longer turn a blind eye to the environmental damage caused by the textile industry. Due to the shift in both consumers and the industry as a whole, the sustainable fashion market is expected to grow to over $3 billion between 2021 and 2025.

The good news is that there are plenty of steps you can take to make your sustainable fashion journey as effortless as Carrie Bradshaw on the streets of the Upper East Side. This list can serve as a guide while you develop more conscious shopping habits.

Secondhand

Going to thrift stores, vintage stores, or closet sales is like a treasure hunt, you never know what you’ll find. Tell the story of a piece without words. The secondhand clothing market is gaining ground, and it’s no wonder, as these pieces add character and uniqueness to our wardrobes while giving new life to clothes that others have already gotten tired of.

Upcycling

Upcycling, also known as value-added recycling, brings out the creative side of eco-conscious consumers. It is an exciting creative process when something completely new is created from discarded rags, from jeans to bags or from old ties to skirts. There are many possibilities in this technique, so it is worth letting your imagination run wild.

Circular fashion

One of the most dominant trends in 2025 is circular fashion. It is a business model that focuses on reducing waste and reusing and recycling resources. The goal is to think about what will happen to clothes at the end of their life cycle and how they can be recycled during the design process. Exciting innovation is taking place in the textile industry in the field of producing biodegradable or compostable fibers. One such innovation is the CELYS compostable fiber, which naturally breaks down into carbon dioxide, water and biomass in 179 days. You can already find products on store shelves that are made from 100% recycled materials, so it’s always a good idea to read the label before buying.

Ethics and transparency

Ethical sourcing means that materials have been sourced without harming people or the planet, and fair trade practices have been applied in farming, production and distribution. In 2025, brands will need to be more transparent about their practices and support their sustainability claims with certifications or third-party audits.

Minimalist fashion

Sustainable fashion brands are increasingly adopting a minimalist aesthetic to eliminate the need for frequent seasonal purchases. This trend is best described by one of our favorite sayings; “less is more”. The main characteristics of the trend are clean lines, neutral colors and timeless designs. The emphasis is on quality, not quantity. In many cases, we don’t even think that we can wear a piece in multiple ways, all we need is the right pairing. Our arsenal of tools is endless, only our imagination can set the limit.

I hope I managed to make you realize that sustainable fashion is not as foreign and boring as you might think at first. Choose the most viable path for you and adopt greener practices!

Written by: Arnóth Nikolett, Fashion Revolution Hungary

Recently, Nextgen Packaging published a white paper on plastic pollution and its impact on the retail industry. Specifically, the paper examines the environmental benefits of transitioning from plastic to paper hangers. It addresses various aspects of business, retail, supply chain requirements, and sustainability. To mark Plastic Free July, Sophie Lundmark explores the findings of the white paper and what it means for the fashion industry.

The Problem at Hand

The retail industry must reduce its plastic consumption, with hangers being a significant contributor. Should retailers and brands adopt sustainable hangers? And why is it crucial to switch from plastic to paper?

Consumer Appeal

Consumers increasingly support sustainable and environmentally friendly companies. Transitioning from plastic to paper products demonstrates a retailer’s commitment to addressing the broader sustainability problem the world faces. As hangers are numerous and very visible in store platforms, the materials used to make hangers should be a serious consideration.

Stakeholder Interest

Recent studies have shown that investors want to put more money into sustainable companies. Companies that are willing to put effort into their ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) strategies are more appealing to consumers and more likely to increase their investor engagement. Retailer commitment has helped push this forward, as many are addressing how to combat and reduce plastic.

Government Legislation

Government regulations on single-use plastic are on the rise globally. Many countries are instituting bans and restrictions on plastic production and sales, including hangers. While the US has fewer restrictive plastic laws, some states, such as California, Hawaii, Maine, New York, and Delaware, are starting to regulate single-use plastics. This trend is important to monitor, as it can affect where and how products are manufactured and used.

Single-Use Plastic

Single-use plastics, intended for one-time use, contribute significantly to environmental pollution. They include items like bags, straws, packaging, bottles, and hangers. The production of plastic involves drilling, extracting, and processing toxic non-renewable resources, emitting greenhouse gases, and causing environmental degradation. After use, plastic hangers can take up to 500 years to degrade in landfills, leaking harmful substances throughout their lifecycle, such as benzene and bisphenyl-a. This can be mitigated by transitioning to paper hangers.

Recycled Plastic

Recycled plastic can be seen as a step up from single-use, virgin plastic hangers. By using recycled materials, manufacturers and retailers can reduce the demand for virgin plastic, lessening the environmental impact. Companies can facilitate this by placing plastic waste collection bins in strategic locations and raising consumer awareness about recycling.

However, recycled plastics still have negative impacts. They are difficult to recycle again due to complex compounds and may contain harmful catalysts and chemicals. These factors should be considered when deciding between plastic and paper.

Alternatives Materials

1. Paper

Paper fiberboard hangers, made from certified wood and/or post-consumer waste, eliminate much of the pollution associated with plastic production. They are lighter and thinner than plastic hangers, allowing more apparel to fit in a single shipment, and reducing greenhouse gas emissions from transportation. Paper hangers can be recycled, biodegraded, or composted, creating a closed-loop system. A natural recyclable paper hanger reduces pollution and effects associated with plastic. They can also be used for branding or advertising with eco-friendly vegetable ink, a benefit no other material has.

2. Wood

Wooden hangers are typically made from renewable trees like oak, maple, walnut, cedar, or bamboo. They undergo an extensive chemical process involving preservatives, stains, sealants, and finishes, and can have metal accessories making the disposal difficult, if not impossible. Although better than plastic, wooden hangers are not as ideal as paper hangers.

3. Metal

Metal hangers, often made from low-grade pot metal, have significant environmental impacts such as habitat destruction and biodiversity loss due to the metal extraction. They, too, undergo processing with toxic paints and varnishes. Recycling centers frequently reject metal hangers because they can tangle and break sorting machines, leading them to landfills where they take 150 years to biodegrade. While metal hangers have a longer lifespan than plastic, they still involve harmful extraction and disposal processes. Paper hangers eliminate these issues.

Findings

Sustainability takes thought, engineering, and time. Today, paper hangers are the best solution for both functionality and sustainability.

The Future

Nexgen Packaging has invested in rigorous research, experimentation, and innovation tactics to come up with the most sustainable and environmentally friendly solutions. Nexgen recently designed their new paper fiberboard hanger that is now available for retailers.

Visit Nexgen’s website to explore their paper hanger story and stay updated with their latest news.

Nexgen Packaging

For inquiries:

Hardy Welch

hardy.welch@nexgenpkg.com

Research done by:

Sophie Lundmark

Isabela State University in Ilagan City is at the forefront of a textile revolution! The Philippine Textile Research Institute (PTRI) has set up a facility there to create yarn and thread from bamboo – a sustainable and versatile material.

This isn’t just about replacing cotton with bamboo. PTRI is blending bamboo with cotton to create unique yarns perfect for clothing. Imagine – government uniforms made with Philippine-developed, eco-friendly bamboo fabric!

Ilagan City’s commitment to sustainability aligns perfectly with PTRI’s vision. The yarn production process is automated, minimizing waste. Plus, they cleverly recycle scraps into new threads! This innovative facility produces 50kgs of yarn every 8 hours, paving the way for a greener textile industry.

The future of textiles is being woven right here in Ilagan City, and it’s made from bamboo!

En Mar del Plata, Argentina – El 30 de diciembre de 2021, el Gobierno Nacional de Argentina aprobó la instalación de petroleras en la costa atlántica bonaerense, cercanas a Mar del Plata y Necochea, generando una gran preocupación en las comunidades costeras y ambientalistas. La aprobación de este proyecto ha llevado a un estado de alerta permanente y a la convocatoria de manifestaciones en todo el país bajo la consigna #Atlanticazo por un #MarLibreDePetroleras.

La industria petrolera se prepara para llevar a cabo la exploración sísmica en busca de hidrocarburos, un paso previo a la explotación y extracción de petróleo en aguas profundas del mar argentino. Sin embargo, este proceso se ha destacado por su alto riesgo para la vida marina y su impacto irreversible en el ecosistema marino.

La Exploración Sísmica: Un Riesgo para la Fauna Marina

La exploración sísmica involucra explosiones de radiofrecuencias muy fuertes que generan daños irreversibles y hasta la muerte de cientos de habitantes marinos. Este proceso invasivo es altamente perjudicial para la biodiversidad marina y plantea graves preocupaciones sobre el bienestar de las especies que habitan en estas aguas.

Las Plataformas Offshore y la Probabilidad de Derrames

Las plataformas offshore, utilizadas para la extracción de petróleo en alta mar, requieren de bombardeos acústicos para detectar la presencia de petróleo. Estos bombardeos, equivalentes a la explosión del despegue de un cohete, causan daños temporales o permanentes a la fauna marina y aumentan el riesgo de extinción de muchas especies. Además, estas plataformas tienen una probabilidad del 100% de derrames, lo que podría tener un impacto devastador en el ecosistema marino y en las actividades económicas de la zona, como el turismo y la pesca.

La Responsabilidad de las Empresas y el Estado Argentino

Empresas como Equinor, en acuerdo con el Ministerio de Economía, el Ministerio de Ambiente, la Secretaría de Energía y los gobiernos nacional y provincial, son responsables de este proyecto petrolero que amenaza al medio ambiente y a las comunidades costeras. Mientras que la ciencia señala la necesidad de transitar hacia un mundo sin combustibles fósiles, este proyecto va en contra de esa tendencia, convirtiendo a Argentina en una zona de sacrificio.

Contexto: Deuda externa Argentina

La deuda externa que Argentina tomó en 2017 bajo el gobierno de Mauricio Macri se ha convertido en un obstáculo crítico para la sostenibilidad financiera del país en 2023. Esta deuda, principalmente en dólares, ha llevado a la necesidad apremiante de adquirir más dólares para cumplir con los pagos, exacerbando los desafíos económicos ya existentes.

En un contexto en el que la economía argentina enfrenta fluctuaciones monetarias y una alta inflación, obtener dólares se ha vuelto cada vez más difícil y costoso. Para hacer frente a esta situación, el país se ve obligado a buscar financiamiento adicional, lo que tiene un impacto negativo en la economía y en la calidad de vida de la población.

La Resistencia: #Atlanticazo

Ante esta amenaza, la Red de Comunidades Costeras ha convocado a la resistencia bajo la iniciativa #Atlanticazo. Se denuncia al Estado Argentino, a las empresas petroleras y a los medios de comunicación hegemónicos que promueven este proyecto ecocida. La resistencia busca evitar la destrucción del ecosistema marino y proteger los bienes comunes de la costa atlántica.

El 4 de octubre de 2023, se llevarán a cabo manifestaciones en diversas ciudades de Argentina y del mundo bajo el lema “Petroleras en el mar NO PASARÁN”. Las comunidades costeras y los defensores del medio ambiente continúan luchando para preservar el mar argentino y garantizar su sostenibilidad.

La lucha por un #MarLibreDePetroleras es un llamado urgente a la acción, no solo para proteger el ecosistema marino, sino también para promover un futuro más sostenible y respetuoso con el planeta. La transición hacia energías limpias y la preservación de nuestros océanos son desafíos clave para construir un mundo más justo y equitativo.

El llamado es claro: el mar argentino está en peligro, y es responsabilidad de todos tomar medidas para protegerlo y garantizar su supervivencia para las generaciones futuras. La lucha continúa, y la resistencia se fortalece en defensa de nuestro mar y nuestro planeta.

Cronograma del #ATLANTICAZO en ARGENTINA – Miércoles 4 de Octubre:

- SAN ANTONIO OESTE: Los Tamariscos en defensa del mar junto a Vuela el Pez Infancias + naturaleza + arte 8:30 hs.

- POSADAS: Plaza 9 de Julio 9 hs.

- NECOCHEA: Puente Colgante 11 hs.

- MENDOZA: Portones del Parque 12 hs.

- LA PLATA: Plaza Moreno a Plaza San Martín 16 hs.

- RIO GRANDE: Plaza Almirante Brown 16:30 hs.

- MAR DEL PLATA: La Rambla 17 hs.

- CABA: De Congreso a Casa de la Provincia de Bs.As. 17 hs.

- PARANÁ: Plaza Alvear 17 hs.

- USHUAIA: Cartel de Ushuaia 17hs. Movilización al puerto a las 17:30hs.

- BAHÍA BLANCA: U.N del Sur, 12 de Octubre y San Juan 17:30 hs.

- PUERTO MADRYN: Fuente de la Rambla 18 hs.

#Atlanticazo en el mundo:

Noruega, España, Holanda, Indonesia, Venezuela, Colombia, México, Ecuador, Brasil, Bolivia, Uruguay, Paraguay y Sudáfrica.

Para más información dirígete AQUÍ

Información en tiempo real en @marlibredepetroleras

La dependencia de la moda a los combustibles fósiles

La moda y los combustibles fósiles están más conectados de lo que podríamos imaginar. La industria de la moda, que abarca desde la producción de textiles hasta la confección de prendas y su comercialización, depende en gran medida de los combustibles fósiles en cada etapa de su ciclo de vida.

- Producción de textiles: La fabricación de fibras sintéticas como el poliéster, el nylon y el acrílico, ampliamente utilizadas en la moda, se basa en la petroquímica, que utiliza petróleo crudo como materia prima. Estas fibras representan una parte significativa de la producción de textiles.

- Procesamiento y teñido: El procesamiento y el teñido de textiles también son intensivos en energía y dependen en gran medida de los combustibles fósiles para alimentar las máquinas y generar calor en los procesos.

- Transporte y logística: La moda es una industria global, lo que significa que la ropa a menudo viaja miles de kilómetros antes de llegar a los estantes de las tiendas. El transporte de materias primas, productos semielaborados y prendas terminadas consume grandes cantidades de energía fósil.

- Comercialización: Las campañas de marketing y publicidad, así como el funcionamiento de las tiendas físicas y en línea, también dependen de la energía derivada de los combustibles fósiles.

Lo que trae como consecuencia:

- Impacto ambiental: La producción de ropa es una de las principales fuentes de contaminación del agua y emisiones de carbono en todo el mundo. La extracción de petróleo para materiales sintéticos y el transporte de prendas a larga distancia contribuyen significativamente a la huella de carbono de la moda.

- Microplásticos: La mayoría de la ropa fabricada con materiales sintéticos libera microplásticos en los océanos cada vez que se lava. Estos microplásticos provienen de fibras de plástico que son derivadas del petróleo.

Este vínculo entre la moda y los combustibles fósiles tiene importantes implicaciones ambientales. La extracción y producción de petróleo crudo y gas natural generan emisiones de gases de efecto invernadero, contribuyendo al cambio climático. Además, la moda rápida, caracterizada por la producción y el descarte rápidos de prendas, agudiza el problema al aumentar la demanda de textiles sintéticos y promover un ciclo de consumo insostenible.

Para abordar esta problemática, la industria de la moda está empezando a explorar alternativas sostenibles, como la producción de textiles a partir de materiales reciclados o renovables y la adopción de prácticas más ecoamigables en la cadena de suministro. La conciencia sobre la necesidad de reducir la dependencia de los combustibles fósiles en la moda está creciendo, y los ciudadanos también están desempeñando un papel crucial al optar por marcas y prendas libres de petróleo.

La relación entre la industria de la moda y los combustibles fósiles en cifras

- Consumo energético: La industria de la moda es responsable del 8% del consumo energético global, siendo una de las mayores consumidoras de energía entre los sectores industriales. Gran parte de esta energía proviene de fuentes de combustibles fósiles.

- Emisiones de carbono: La moda contribuye al 10% de las emisiones globales de carbono, lo que la convierte en una de las industrias más contaminantes, incluso superando a la industria aérea y marítima combinadas.

- Producción de fibras sintéticas: La producción de fibras sintéticas, como el poliéster y el nylon, que provienen del petróleo, representa aproximadamente el 65% de todos los materiales utilizados en la industria de la moda.

- Transporte: El transporte de productos de moda a nivel internacional requiere una cantidad significativa de combustibles fósiles. En 2019, se estimó que la industria de la moda emitió alrededor de 1.400 millones de toneladas de dióxido de carbono debido al transporte.

- Desperdicio: Cada año, se producen alrededor de 92 millones de toneladas de desperdicios textiles, y gran parte de estos desperdicios son incinerados o enviados a vertederos, liberando dióxido de carbono a la atmósfera.

- Microplásticos: Se estima que el lavado de prendas de materiales sintéticos libera hasta 500.000 toneladas de microplásticos en los océanos cada año, además la ropa y los textiles son la fuente número 1 de microplásticos en los océanos, siendo el 34,8% del total global, lo que agrava aún más el problema de la contaminación por plásticos.

Estas cifras muestran la magnitud del impacto ambiental de la industria de la moda en términos de consumo de energía, emisiones de carbono y contaminación por microplásticos, todos los cuales están relacionados con la dependencia de los combustibles fósiles. Es esencial abordar estos problemas para lograr una moda limpia y reducir su huella ecológica.

Por estas razones te invito a revisar las etiquetas de composición de tus prendas y pregunta a las marcas #QUEHAYENMIROPA

Fuentes:

Red de Comunidades Costeras a través de la Coordinadora @bastadefalsassoluciones

¨Historia de la deuda externa Argentina¨ Wikipedia en Español

In today’s day and age, beauty is no longer pain. Convenience and comfort are everything, especially in fashion; clothing is optimised to fit the latest trends and be readily accessible. When first impressions are often initially based on appearance–especially when it comes to youth–shoes, shirts, pants, and skirts become that much more critical. We shop in a world where everything is fast-paced and disposable–but at what cost? Well, all we have to do is take a look at the numbers: with Gen Z’s $360 billion purchasing power, we make up nearly 40% of all textile consumers, which contributes to almost 1.48 billion metric tons of global CO2 emissions yearly [1]. Coupled with the mounting concerns for the human rights of garment workers, particularly those in Eastern and Southern Asia, it becomes clear that fashion is anything but convenient, sustainable, or ethical, especially when it comes to the planet and those working in the industry on-ground. However, with Gen Z becoming increasingly alarmed by the climate crisis and looking for more sustainable clothing items, technology has emerged as a saving grace. Let’s take a look at four new fabrics that are transforming textiles for the better of the planet and its people.

Mushroom-y Fabrics

At the heart of the fungi kingdom lies a hidden hero: mycelium, the root-like structure of mushrooms that spreads its spidery threads beneath the earth’s surface. This complex network is more than just a fungal footprint; it’s a bustling hub of biological activity, breaking down organic matter and turning it into nutrient-rich soil. But here’s the game-changer: scientists and fashion gurus are now harnessing this natural decomposer, turning it into a sustainable source for textiles.

The process, while intricate, is surprisingly straightforward. Mycelium is grown on a diet of organic waste, taking shape in vast cultivation trays. For weeks, it expands, weaving a dense network of fibres that can be harvested, treated, and finally, transformed into a material remarkably similar to leather. The result? A versatile, durable, and most importantly, sustainable fabric that could revolutionise the fashion industry.

And the numbers are equally promising. A 2018 study found that mycelium-based materials have a CO2 equivalent footprint up to 40 times lower than cattle leather and nearly half that of synthetic leather [2]. With the fashion industry responsible for 10% of annual global carbon emissions [3], the potential impact of mycelium-based textiles could be significant.

Indeed, the promise of mycelium has not gone unnoticed by the fashion industry. Pioneering companies like MycoWorks and Bolt Threads are redefining the boundaries of sustainable fashion with their mycelium-based textiles.

California-based MycoWorks, for example, uses a patented process to grow mycelium into a material they call Fine Mycelium™. This material can be customised to different thicknesses, textures, and levels of durability, which can be adapted to various fashion needs. The company’s groundbreaking technology caught the eye of the luxury sector when they collaborated with a luxury brand to create the world’s first bag made entirely from mycelium-based leather [4].

On the other hand, Bolt Threads, another pioneer in the field, has developed Mylo™, a mycelium-based material that closely mimics the properties of animal leather. They’ve already made significant strides, partnering with major brands to create prototype products, marking an important step towards mainstreaming this sustainable material [5].

Colourful Bacteria

In the realm of sustainable fashion, it’s not just about the fabric – the dyes matter too. Traditional dyeing processes often involve toxic chemicals and vast amounts of water, making them a significant environmental concern. Enter Streptomyces coelicolor, a soil-dwelling bacterium with the potential to revolutionise the textile dyeing process. This remarkable microbe produces a rainbow of pigments as part of its normal life cycle, from vibrant blues and reds to subtle yellows [6].

Scientists have found a way to harness these natural pigments, fostering the bacteria in a nutrient-rich medium. As the bacteria multiply, they secrete pigments that can be collected and used to dye textiles, completely bypassing the need for harmful synthetic dyes. This innovative process promises a significant reduction in the environmental footprint of textile dyeing.

One company leading the charge in microbial dye technology is Colorifix. Using a similar process to that of Streptomyces coelicolor, they’ve genetically modified microbes to convert sugar into pigments, which are then fixed onto fabrics without the need for heavy metals or complex chemical mordants. This process requires up to 10 times less water than traditional dyeing methods and produces minimal wastewater [7].

Meanwhile, design agency Faber Futures is using Streptomyces coelicolor to not just dye fabrics but to create them. Their project, “Colour Coded,” explores the potential of using bacterial pigments to pattern textiles, weaving sustainability and design into a single, seamless process [8].

This innovative use of bacterial pigments is making the fashion industry not just more colourful, but significantly greener. With these developments, we step into a future where the vibrancy of our clothes is matched only by the sustainability of their production.

Sugar Sweet Rubber

When we think of sugar cane, sweet treats probably come to mind before sustainable fashion. Yet this humble plant is making big waves in the industry, specifically in the form of sugar cane rubber. This bio-based alternative to conventional rubber is derived from the juice of the sugar cane plant, which is fermented and distilled to produce ethanol. This ethanol is then converted into ethylene, a key ingredient in the production of rubber [9].

The benefits of sugar cane rubber are multi-faceted. From an environmental perspective, sugar cane is a renewable resource that absorbs CO2 as it grows, which can help offset the carbon emissions from rubber production. Additionally, the process of making sugar cane rubber requires less energy compared to traditional methods, resulting in lower greenhouse gas emissions [10].

From a worker’s rights perspective, sugar cane cultivation can be a more sustainable option. Many countries that produce sugar cane have established labour laws and regulations to protect workers, in contrast to the often hazardous conditions faced by workers in the traditional rubber industry.

The move towards sugar cane rubber is an exciting step towards more sustainable fashion. It’s a testament to how creativity and innovation can transform something as simple as a sugar cane stalk into a tool for environmental change.

(Un)Conventional Crops

When it comes to sustainable fashion, there’s a lot to be said for going back to basics, and organic cotton is a prime example. This natural fibre is grown without harmful chemicals, using methods and materials that have a low environmental impact. It’s a shift away from conventional cotton farming, which heavily relies on water and toxic chemicals, contributing to water contamination and soil degradation [11].

Organic cotton farming takes a more holistic approach, focusing on replenishing and maintaining soil fertility while using less water, largely due to healthier soil having better water retention. This method also promotes biodiversity and builds biologically diverse agriculture, a stark contrast to the monoculture of conventional cotton farming [12].

The benefits of organic cotton extend to the people involved in its production as well. Farming without harmful chemicals means healthier soils, water, and workers. Moreover, many organic cotton farmers are part of cooperatives, where profits are shared, and farming practices are collectively decided, often leading to fairer wages and safer working conditions [13].

Organic cotton is a testament to the value of revisiting traditional farming methods in the pursuit of sustainability. It’s a reminder that sometimes, the most effective solutions are not about reinventing the wheel but respecting and working with the natural systems already in place.

Shaping the Future

Whew! We haven’t even covered everything here, like textiles made from oranges (yes, the fruit!) and soy-based fabrics. However, as we close our exploration of these five transformative fabrics, it’s clear that fashion’s future is evolving. It’s a future where the beauty of our clothing doesn’t come at the cost of our planet. It’s a future where fashion’s convenience and comfort extend beyond the wearer to include the hands that craft our clothes and the earth that yields the materials. In this new age, fast-paced and disposable are giving way to slow, mindful, and sustainable.

As consumers, particularly the youth with our substantial purchasing power, we hold the key to shaping this future. Our choices can fuel the demand for these innovative and sustainable materials, and also shine a light on those who have the moral burden of making up for the damage that’s been done: the brands themselves, who need to listen to their customers and change their business models. Consider opportunities like Fashion Revolution’s #WhatsInMyClothes campaign, which empowers citizens to ask brands what their clothes are made of and how they impact the environment.

The intersection of technology and sustainability has indeed proven to be fashion’s saving grace. Let’s continue to support, advocate, and if able, invest in these fabrics of the future, transforming not just our wardrobes, but our world, one thread at a time.

Take Action

Download a poster to ask #WhatsInMyClothes on social media

View this post on Instagram

References:

- Gen Z Has $360 Billion to Spend, Trick Is Getting Them to Buy

- Life Cycle Assessment of Mycelium-Based Leather

- UN Environment – Fashion Industry’s Carbon Impact

- Hermès Launches Bag Made of Lab-grown Mycelium Leather

- Adidas Partners with Bolt Threads

- Pigmented Antibiotics Produced by Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2)

- Colorifix Official Website

- Faber Futures – Colour Coded

- Sugar Cane Rubber – An Overview

- The Environmental Impact of Sugar Cane Rubber

- The Impact of Cotton on Fresh Water Resources and Ecosystems – WWF

- Why Organic Cotton – Textile Exchange

- Fair Trade Certified – Organic Cotton

Header image by Bryony Elena on Unsplash

This article was written by Fashion Revolution Brasil. You can read the Portuguese version here.

Deforestation of more than 10,000 km² and humanitarian crisis in the Amazon

In 2022, more than 10,000 km² were deforested in the Amazon region: the equivalent of cutting down nearly 3,000 soccer fields per day of forest. This destruction threatens the region’s biodiversity, rainfall, health and food security for millions of people and further intensifies the effects of the global climate crisis.

Even in the midst of this worrying scenario, none of the 60 brands analysed in the Fashion Transparency Index Brazil 2022 disclose commitments to zero deforestation and only 8% of the brands disclose public lists of their raw material suppliers. Companies have the responsibility to look over their supply chains, identify potential risks and impacts to human rights and the environment, and address them. The lack of visibility on these topics opens up gaps for environmental and social damage to occur.

Based on the idea that development is intrinsically linked to economic growth, increased production capacity and profit, the natural, social and cultural wealth of the Amazon region remains under threat. Indigenous peoples, who act as protectors of forests and shields against deforestation, are having their rights dismantled and their population seriously impacted by the advance of livestock, agriculture and mining.

Next, we bring more information on what is happening in the Amazon and how this devastating scenario relates to fashion.

View this post on Instagram

#WhatsInMyJewelry and the Yanomami tragedy

Data from Map Biomas shows that, between 1985 and 2020, the mined area in Brazil grew six times. This expansion of mining coincides with its advance on indigenous territories and conservation units. From 2010 to 2020, the area occupied by mining inside indigenous lands grew by 495%.

The impacts of deforestation, the destruction of water streams and the illegal extraction of gold is evident in the Yanomami territory. The Yanomami are an indigenous group that lives in the north of the Amazon region and have become the target of a serious humanitarian crisis. In addition to various environmental impacts, the Yanomami face hunger, malnutrition, an increase in cases of malaria and other infectious diseases, mercury contamination and a growth in violence against indigenous people surrounded by illegal mining.

Traceability and transparency in the gold and precious metals supply chain is precarious. The ore extracted clandestinely from Brazilian indigenous lands can end up in jewelry or electronic filaments used around the world. After having its real origin covered up, the metal is mixed with legalized gold in refineries, enters the international market and can be acquired by large global companies without them being able to trace its real origin.

The opaque traceability only reinforces the importance of companies carrying out robust due diligence processes for human and environmental rights in their supply chains. Transparency is needed across the entire fashion value chain. Questioning the origin of what we wear goes beyond just our clothes and should also include our accessories. We should ask the brands #WhatsInMyJewelry

New infrastructure project could worsen local situation

Another example of how the relentless pursuit of profit and increased production efficiency can negatively impact the environment and local communities is a project that is expected to be voted on by the Brazilian Federal Supreme Court at the end of May: the Ferrogrão. The approval of the project could further accentuate the critical situation of devastation in the Amazon.

Ferrogrão is a project for the construction of a railroad of almost a thousand km to transport grain from Mato Grosso to Pará. One of the objectives of the infrastructure project is to increase economic efficiency in the distribution and storage of grains, given the expansion of the Brazilian agricultural frontier.

The project is sold as a green tunnel, but privileges the interests of the agribusiness market to the detriment of the preservation of the environment and the guarantee of ethnic and territorial rights. If it is constructed as planned, Ferrogrão will cross the Jamanxim National Park, a Conservation Unit of Full Protection. The railroad could also intensify land conflicts and potentiate socio-environmental impacts already suffered in the region. At least three ethnic groups would be impacted by the construction of the railroad (Munduruku, Kayapó, Panará) and there is a risk of deforestation of more than 230 thousand hectares.

These and other impacts with the potential to accelerate the expansion of the agricultural frontier and the intensification of the production of commodities based on monoculture and land concentration have already been denounced by indigenous peoples.

Transparency, consciousness and dialogue

Amidst this worrying scenario of devastation, in which biodiversity and local communities remain threatened, we need fashion brands to take a stand and be transparent about the origin and traceability of their products.

We need transparency about where what we consume comes from. We need to rethink the logic of profit. We need a development model that considers the nature and culture of people as a value and an element capable of generating socioeconomic well-being in the long term. We need to include affected peoples in the dialogue for improvements, consulting with them before projects can be approved. We need government oversight and public policies that favor Nature and people.

We invite you to ask the brands #WhatsInMyJewelry, #WhatsInMyJewelry and accessories, demanding transparency about the production processes. You can also make donations to help the Yanomami people and sign this petition against the construction of Ferrogrão.

Further reading

How transparent are the world’s 250 largest fashion brands?

The 2022 Global Fashion Transparency Index

The 2022 Brasil Fashion Transparency Index

This is a guest post by Denica Riadini-Flesch, the founder and CEO of SukkhaCitta, an award-winning social enterprise that changes lives in rural Indonesia: Working directly with craftswomen and smallholder farmers, through natural dyes and regenerative farming, she is changing the way clothes are grown, made, and worn – empowering the makers while respecting planetary boundaries, and providing direct access to education and living wages to the most marginalised women in villages, not factories.

We’ve lost touch. With where things come from. With the journey our clothes take before we wear them. And the true cost our choices have on the planet.

As a development economist, my work took me through rural Indonesia. There, for the first time I saw how our clothes are made: by women working from home. Mothers who are continuing the heritage traditions of their ancestors. Hands who are slowly disappearing as it is estimated that 98% of women who make our clothes don’t earn a living wage.

But perhaps what was shocking to me was how dirty the industry is. Every day, tons of toxic chemicals are used to dye our clothes. Entering our water sources without any treatment, into the same rivers the communities use to irrigate our food and sustain life. A reality that is hidden to us, even as it creates 20% of the world’s water pollution.

This was the moment I realised I needed to build a bridge. Between you and the women who make your clothes. Providing access to education and fair work, so they can lift themselves out of poverty while protecting our environment through plant dyes.

What if our clothes can heal the planet?

Two years ago, our world changed. In the midst of all the crisis, one thing became painstakingly clear: Sustainability is no longer enough. There was no point in sustaining a broken system. Now more than ever, we need to find ways to go beyond protecting, investing in regeneration to heal our relationship with nature.

That was when we learnt that 99% of cotton in Indonesia is imported. Which is an irony considering our history as a cotton producer. And it’s grown in ways that work against Nature. In massive, chemical-laden monocultures that deplete our soil and cause climate change. Not to mention the rampant stories of exploitation woven into our clothes.

But when we met some of Indonesia’s last cotton farmers, we learned that there is a better way. Together, we rediscovered principles like Tumpang Sari: Our ancestral agricultural regenerative farming wisdom. Using herbal pesticides made of cloth and salt and natural fertilizer. A reciprocal relationship designed to give back to the soil.

Tumpang Sari: Working With Nature

Nature is full of cycles. Regenerative farming is an indigenous system of agriculture that restores the soil’s health and resilience. Building a reciprocity that allows the ecosystem to draw down more carbon from the atmosphere to reduce global warming.

It is a way of growing things that is all about soil health. Because healthy soil is not only key to happy smallholder farmers. It’s essential to life as we know it (think: food on the table). This process restores the balance between soil and the atmosphere. What’s wrong with that balance, you may wonder? One word: Carbon.

Because of the way we humans do things right now, carbon levels in the soil have depleted and increased dramatically in the atmosphere – creating all kinds of problems. The soil actually needs more of it (because carbon helps soil store water and actually grow the food we eat), while the atmosphere has roughly 109 billion tons too much, causing global warming, rising sea levels, extreme weather events, flooding and more.

Through regenerative agriculture we take that excess carbon out of the atmosphere and put it back into the soil – regenerating it and allowing it to sustain life again! It’s a process called carbon sequestration, is 100% natural and has been nature’s way for managing carbon for eons.

Farm-to-Closet: Investing in Regeneration

Since 2020, we’ve been working to help women farmers transition from conventional farming to Tumpang Sari. When we started, the land was dry and chemically-damaged. But now, a new hope is growing throughout the whole community.

Our cotton is grown together with 23 different plants to create a diverse agroforest ecosystem. From Marigold flowers as pollinator crop, cassava and corn as cover crops, to cloves and chillies as trap crops to protect the cotton from pests.

To nourish the soil, our Ibus create an organic compost from organic waste from the farm. While treating infected crops using her grandmother’s potent recipe of clove, salt and water. A holistic system where each plant, insect, and microorganism have their unique role in this journey of regeneration.

Ibu Kasmini’s story: Smallholder farmers against climate change

“Kene ngerawat Bumi, podo karo ngerawat awe’e dewe”

When we take care of Mother Earth, we take care of ourselves.

– Ibu Kasmini

For smallholder farmers like Ibu Kasmini, returning to the way of her ancestors has been a blessing. She no longer has to buy expensive chemicals – and her cotton yield has increased six times. Sustaining indigenous wisdom while creating long lasting benefits for our planet.

Why this matters

Traceability is where change starts. The long journey it took us to change how your clothes are grown showed us how knowing exactly where something came from – and especially in what conditions – is the first step towards creating real change.

It’s shown us the potential that fashion can have. That when done right, it can be a solution to some of the world’s most pressing issues. That together, we can weave economic empowerment to those who need it most while respecting our planetary boundaries.

And it all starts with a choice. What will yours be today?

Further Reading:

Challenges facing the farmers who grow our cotton

Lessons from the Cotton Diaries

Mary Pierson, a Madewell brand farmertervezésért felelős alelnöke szerint a skinny jeans csillaga leáldozóban van, és egyre népszerűbbek a bő-, vagy egyenes szárú fazonok, valamint a nehezebb, kevésbé rugalmas és nem nyúló farmerek. Bár a fogyasztók fizikai és érzelmi megnyugvást éreztek abban, hogy kényelmes ruhákba bújtak a világjárvány korai hónapjaiban, a COVID-19 nem az egyetlen tényező a bővebb, lazább darabok felé való elmozdulásban. „A skinny trend olyan sokáig volt domináns, hogy a váltás már elkerülhetetlen” – mondta Pierson.

Bő, bővebb, legbővebb

A bővebb fazonok trendjének első jelei évekkel korábban jelentek meg a kifutón, amikor az olyan streetwear orientált tervezők, mint például Virgil Abloh és Heron Preston megvették a lábukat a luxuspiacon, drága designer címkével felvértezve a műfaj jellegzetes esztétikáját.

Ha hozzáadjuk a nemek nélküli design általános érvényesítésére való igényt (amely nagymértékben támaszkodik a „dobozszerű”, munkaruha-ihlette sziluettekre), és a milleniálok ’90-es évek iránti nosztalgiáját, valamint a „csúnya” cipők térnyerését – a szélesebb, lazább, bővebb stílusok divatjának megérkezése és hatalomra kerülése nem is annyira meglepő.

A cselekmény csavarja azonban a gyorsaságban és a mindent uraló egyediségmániában rejlik: míg korábban az emberek csak jóval lassabban vettek át és szoktak meg trendeket, ma már a közösségi médiának, és a járványt követő „végre ki lehet öltözni”-felszabadulásnak köszönhetően minden felgyorsult és egyedileg determinált lett. Az így létrejövő trendciklus szerint ma már BÁRMIT viselhetünk, amit jónak látunk.

„Ebben a pillanatban nem merítünk ihletet senkitől, csak magunktól” – mondta Zihaad Wells, a True Religion kreatív igazgatója. A Ricky egyenes farmer továbbra is a True Religion első számú darabja, mert nemcsak a márka eredeti stílusára, hanem a divat aktuális alakulására is rímel. „Nyilvánvaló, hogy a farmer 2022-es új trendciklusában a múlt üdvözlése történik” – mondta Wells, hozzátéve, hogy a True Religion olyan archív stílusokkal elégíti ki a nosztalgia iránti igényt, mint a rövid szabású nadrágok a női fazonoknál vagy a férfiaknál a bő sziluettek.

A Favorite Daughter design igazgatója, Carla Calvelo egyfajta előrejelzésként kifejtette, hogy a ’90-es és 2000-es évek nagy hatást gyakoroltak erre az évre: a laza, túlméretezett, bootcut és egyenes szárú stílusok mindent visznek idén. A márka folytatja a magas derekú és hosszúkás sziluettek gyártását. Hozzátette, a testreszabott illeszkedések irányába való elmozdulás továbbra is izgatja a fantáziáját.

Ugyanez a korszak szűrődik át a 2022-es Joe’s Jeans kollekciókon is – és ez komfortzóna Alice Jackman, a márka design igazgatója számára. „Több mint 20 éve dolgozom a farmeriparban, így a ’90-es évek végén és a 2000-es évek elején tapasztalt tervezési folyamatok nagy része az első pillanattól kezdve ismerős számomra” – mondta. A Joe következő kollekciói lazább és szélesebb illeszkedést kínálnak a trendciklusnak megfelelően. A márka egy új „Heirloom” nevű szövettel is dolgozik, amely Jackman szerint kiemelkedő farmer twill vonallal rendelkezik, rendkívül puha érzettel és rugalmassággal.

„Remek erőforrásaim vannak itt Los Angelesben a vintage kapcsán, ezért mindig fedezek fel csodás koptatott darabokat, amelyekből lehet inspirálódni a modern farmerek gyártásakor” – tette hozzá.

Eközben Steffan Attardo, a márka férfi design igazgatója szerint a régi iskola divatja vezérli a Hudson Jeans új irányát. A festék fröccsenése, a roncsolás és a bevonatos szövetek a brand közelgő kollekcióinak részei lesznek, de az igazi hangsúly a bő illeszkedések kialakításán van.

„A szélesebb szárú szabás az új mainstream” – hangsúlyozta Attardo.

Közösségi háló

A múlt ihletet ad, de a Z generáció az, amely másolja és relevánssá teszi az Instagramon és a TikTokon lévő közösségi megafonjain keresztül az „új-régi” trendeket.

Noha a közösségi média már a 2000-es években is közvetítette a divatot a Tumblr-rel az élen, a jelenlegi platformok nagyobb jelentőséget kaptak a fogyasztók és a márkák számára – ezek által nemcsak közvetítik, hanem megteremtik, majd remixelik is a trendeket.

„A közösségi média valóban a folyamatosan megjelenő új trendek katalizátora lett” – mondta Sarah Ahmed, a DL1961 társalapítója és kreatív igazgatója. „Olyan gyorsan és egyszerűen oszthatók meg az új információk és innovációk, hogy nem csoda, hogy a farmertrendek ilyen ütemben változnak.”

A farmertrendek gyors átalakulása a DL1961 javára szól. Februárban a New York-i székhelyű márka bemutatta első farmercsaládját, amely hulladék pamutszálakból készült. Stílusuk középpontjában a széles szár, a bootcut, a kiszélesedő és az egyenes szabás áll. „Mivel a gyártás nálunk egy fedél alatt, a családi tulajdonban lévő pakisztáni gyárunkban zajlik, könnyen módosíthatunk, és szükség esetén gyorsan alkalmazkodhatunk az új stílusokhoz és trendekhez” – mondta Ahmed. Kiemelte még, hogy minden az információ terjedésének sebességéről és a farmergyártás technológiai fejlődéséről szól, amely lehetővé teszi számukra, hogy lépést tartsanak a változásokkal.

A buborék kipukkanása

Minden győzelmi sorozatnak vége szakad, és a tervezők arra számítanak, hogy a farmerbuborék hamarosan kipukkanhat, mint ahogyan azt már az iparágban megjelent, majd gyorsan eltűnt trendek esetében nem egyszer tapasztalhattuk.

Pierson hozzátette, korábban elvárás volt, hogy egy farmerszabás vagy -trend legalább öt évig, esetleg tovább tartson, de ma már ez nincs így, hiszen a vásárlók és az egyéb ruhaneműk trendjei is gyorsan átalakulnak. Noha nem biztos, hogy a fogyasztók gyorsan elfelejtik az aktuális farmerirányzatot – Pierson szerint a következő egy-két évben az egyenes, széles és kiszélesedő szárú farmerek lesznek a középpontban.

Így vagy úgy, de tény, hogy a farmer sosem megy ki a divatból. Ugyanakkor, mint tudjuk, a farmer negatív hatással van a környezetre, mivel szennyezi a vizeket a gyártásához használt festékek miatt, ezenkívül az anyag előállításához használt gyapottermés sok vizet, valamint vegyi növényvédő szert igényel.

Tekintettel arra, hogy a szűz farmer az egyik legkevésbé fenntartható szövet a piacon, az újrahasznosított farmer lehet a környezetbarát alternatíva. A posztindusztriális farmerszövet használata kiküszöbölheti a környezetszennyező előállítási folyamatokat.

A cikk eredeti verziója a Rivet 2022-es tavaszi számában jelent meg.

Fordítás, szerkesztés: Zahorján Ivett

This is a guest post from Kate Turnbull, natural dyer and Head of Fashion and Textiles Design at Headington, Oxford, who developed the natural dyes for the Textile Garden for Fashion Revolution.

Textiles, dyeing and printing are in my blood. My great grandfather John Tomkinson was the co-founder of The Premiere Dye Works in Leek, Staffordshire. He trained with the world-famous Sir Thomas Wardle, known for his innovations in silk dyeing and printing on silk and his collaboration with William Morris, who visited the Premiere to learn how to use natural dyes. During WW2, The Premiere were responsible for dyeing the uniforms for the British army and eventually sold to Dupont in 1970s.

Growing up, I was always fascinated with this story, a fascination that grew when I found a copy of one of John Tomkinson’s prized dye books as an art student at which point I resolved to follow in his footsteps. I went on to train at Central St Martins where I first learnt about sustainable textiles and based my entire thesis on the damaging effects of textiles on the fashion industry and championing traditional silk screen printing methods for slow fashion. Sadly, John Tomkinson died aged 52 from lung cancer, most probably related to the chemicals used in the factory. (I turn 52 in July!) My mission is to pick up where he left off, but using natural dyestuffs and in my own small way both as a practitioner and an educator, to make a difference to the impact that textiles have on our planet.

Sustainable textile education

As an educator, my aim is to give the students the best grounding possible in sustainability and design. For many years there has been a growing realisation that the chemicals used in the classroom were both unnecessary and harmful, and as the awareness of the toxicity of the textile industry has grown, we felt it was time to shake things up in the Headington curriculum. It began with simple changes, such as embargoing aerosols, acrylic paints and synthetic materials and then through lockdown we were able to focus on how to re-engineer the course and maximise the potential for a comprehensive Eco-Textiles education. We began extracting and dyeing with colour from plants and making inks from berries and foraged botanicals. We now make all of our own colours to dye with, our own ink, glue and print pastes and we up-cycle old sheets to dye and construct garments with.

Recently – I am absolutely thrilled to report – all our hard work has been recognised, as I have been shortlisted in the TES School Awards as Subject Lead of The Year, which of course is recognition for the whole department as well as the students, who have embraced the course so wholeheartedly. Our brand new Eco Textiles cohort is thoroughly invested in both sustainable and ethical textiles, so much so that my dream of inspiring other schools to include this in their A-Level curriculum is beginning to feel tangible. Using this exciting spotlight on Headington, I hope I can reach out to other teachers interested in educating our young minds about the damaging effects of the Fashion and Textiles industry. Plus, one of the benefits of running the course like this, is that it costs so little in relative terms, making it accessible for everyone. We even have a gardening club where students from year 7 onwards sow and grow our very own dye plants.

The most exciting project of all is the opportunity the students have had to work with garden designer Lottie Delamain and Fashion Revolution, who have created A Textile Garden for Fashion Revolution, Chelsea Flower Show’s first-ever dye garden showcasing plant fibres that can be used to make clothing.

Why we need natural dyes

The production of polyester is an energy-intensive process producing high levels of greenhouse gas emissions, while wastewater emitted from polyester processes contain volatile substances that can pose a threat to human health. Despite this, Fashion Revolution’s Fashion Transparency Index 2021 found that only a quarter of major brands publish time-bound, measurable targets on reducing the use of textiles deriving from virgin fossil fuels. In my opinion, that is really not good enough and I hope that the symbolism and message of Lottie’s garden cuts through to the stakeholders and change-makers in the industry.

Lottie’s philosophy for the garden matches mine – it is about seeing the potential in the resources we have on our doorstep and exploring how we can utilise them in more creative ways as alternatives to synthetic, petroleum-based fabrics and chemical dyes. Many of the plants are native wildflowers, easily propagated and grown in the UK and undemanding in terms of water.

Bringing the garden to life

For the garden, my students and I have foraged and dyed linen panels, to be suspended above the dye plants in the garden. We have used different parts of the plant to demonstrate how versatile botanicals can be in terms of extracting colour. For the yellow panels, daffodil and dandelion heads were used. For the rust colour, rhubarb roots, for the pink cherry bark and madder roots (grown for three years in my garden for optimal pink) and for the green we gently simmered nettle leaves with a copper modifier. For the backdrop, we made a large 8m x 4m panel, hand-stitched together with reclaimed vintage Irish linen sheets. Lottie & I were keen to keep this in a simple grid-like formation, to reflect the Annie Albers influence of the garden. These were specifically un-dyed, to allow the panels to really sing out and to mirror the flax growing in her garden, which of course is spun and woven to make linen; a circular process.

Once the backdrop had been completed, I realised I had just enough linen left to make some garments, so I decided to hand dye it into three colours, one each for Lottie, Carry and me. I wanted the colour to be personal to each of us and, while I was pondering this, we received an exciting invitation to take part in the fantastic Wardrobe Crisis podcast, hosted by Clare Press. In the episode, our first question was to tell a ‘plant love story’. Lottie described how she had fallen in love with Cutch trees when she lived in Vietnam and Carry’s plant of choice was Weld, which she loves for connections to her Irish ancestry, for which she is writing a book about. I talked about ‘Sakura’ Cherry Blossom and the Hanami Festival I visited in Japan, inspired by the Threads of Gold Exhibition at The Ashmolean several years ago. I had my answer! Lottie’s linen was dyed in Cutch, Carry’s in Weld and mine in Cherry Blossom bark. I am lucky enough to be friends with slow Fashion designer Anna Mason. I contacted her to see if she would make up the fabrics into garments for us from her collection. She agreed! I can’t wait to surprise Lottie and Carry with the clothes they can wear to the Chelsea Flower Show, to demonstrate everything can be locally sourced, grown dyed and made for sustainable and ethical fashion.

After Chelsea Flower Show, the garden will be relocated to Headington, where it will become a permanent feature in the school and also have a working dye garden where students can forage for dye material for the Eco Textiles course as well as learn about gardening.

Further Reading

A Textile Garden for Fashion Revolution

Behind the scenes: Creating our textile garden at Chelsea Flower Show

The true cost of colour: The impact of textile dyes on water systems

Nature in Freefall: How Fashion Contributes to Biodiversity Loss

This article was originally published on The Conversation by Dr Tom Stanton, researcher for the Restorying Riverscapes project

We have all become more aware of the environmental impact of our clothing choices. The fashion industry has seen a rise in “green”, “eco” and “sustainable” clothing. This includes an increase in the use of natural fibres, such as wool, hemp, and cotton, as synthetic fabrics, like polyester, acrylic and nylon, have been vilified by some.

However, the push to go “natural” obscures a more complex picture.

Natural fibres in fashion garments are products of multiple transformation processes, most of which are reliant on intensive manufacturing as well as advanced chemical manipulation.

While they are presumed to biodegrade, the extent to which they do has been contested by a handful of studies. Natural fibres can be preserved over centuries and even millennia in certain environments. Where fibres are found to degrade they may release chemicals, for example from dyes, into the environment.

When they have been found in environmental samples, natural textile fibres are often present in comparable concentrations than their plastic alternatives. Yet, very little is known of their environmental impact.

Therefore, until they do biodegrade, natural fibres will present the same physical threat as plastic fibres. And, unlike plastic fibres, the interactions between natural fibres and common chemical pollutants and pathogens are not fully understood.

Fashion’s environmental footprint

It is within this scientific context that fashion’s marketing of alternative fibre use is problematic. However well-intentioned, moves to find alternatives to plastic fibres pose real risks of exacerbating the unknown environmental impacts of non-plastic particles.

To assert that all these problems can be resolved by buying “natural” simplifies the environmental crisis we face. To promote different fibre use without fully understanding its environmental ramifications suggests a disingenuous engagement with environmental action. It incites “superficial green” purchasing that exploits a culture of plastic anxiety. Their message is clear: buy differently, buy “better”, but don’t stop buying.

Yet the “better” and “alternative” fashion products are not without complex social and environmental injustices. Cotton, for example, is widely grown in countries with little legislation protecting the environment and human health.

The drying up of the Aral Sea in central Asia, formally the fourth largest lake in the world, is associated with the irrigation of cotton fields that dry up the rivers that feed it. This has decimated biodiversity and devastated the region’s fishing industry. The processing of natural fibres into garments is also a major source of chemical pollution, where factory wastewaters are discharged into freshwater systems, often with little or no treatment.

Organic cotton and Woolmark wool are perhaps the most well known natural fabrics being used. Their certified fibres represent a welcomed material change, introducing to the marketplace new fibres that have codified, improved production standards. However, they still contribute fibrous particles into the environment over their lifetime.

More generally, fashion’s systemic low pay, deadly working conditions, and extreme environmental degradation demonstrate that too often our affordable fashion purchases come at a higher price to somebody and somewhere.

Slow down fast fashion

It is clear then that a radical change to our purchasing habits is required to address fashion’s environmental crisis. A crisis that is not defined by plastic pollution alone.

We must reassess and change our attitudes towards our clothing and reform the whole lifecycle of our garments. This means making differently, buying less and buying second hand. It also means owning for longer, repurposing, remaking and mending.

Fashion’s role in the plastic pollution problem has contributed to emotive headlines, in which purchasing plastic-fibred clothing has become highly moralised. In buying plastic-fibred garments, consumers are framed complicit in poisoning the oceans and food supply. These limited discourses shift accountability onto the consumer to “buy natural”. However, they do little to equally challenge the environmental and social ills of these natural fibres and the retailers’ responsibilities to them.

The increased availability of these “natural” fashion products therefore fails to fundamentally challenge the industry’s most polluting logic – fast, continual consumption and speedy routine discard. This only entrenches a purchasable, commodified form of environmental action – “buying natural”. It stops the more fundamental reassessment of fast fashion’s “business as usual”, that we must slow.

Let me explain how this is greenwashing: “Regular cotton is full of toxic chemical [sic] like chlorine, carcinogens, and other chemicals. We use certified GOTS cotton, which has none of those harsh chemicals. Our garments are 100% toxic-free.” This is wrong. Here’s why:

— Alden Wicker (@AldenWicker) May 3, 2022

Further Reading

Greenwashing & The Fashion Industry’s Impact on the Environment

Challenges facing the farmers who grow our cotton

Our clothes shed microfibres – here’s what we can do…

This is a guest blog post by Ismay Mummery, founder of Boy Wonder.

You may have come across the word ‘regenerative’ combined with agriculture, but what is regenerative fashion? Why is it the latest buzzword and which fashion brands are doing it?

How Does Regenerative Agriculture Relate To Fashion?

The fashion and textile industry is heavily reliant on our agricultural systems, from land producing cotton crops to sheep producing wool. Cotton, for example, is the most used fibre in the world and uses 2.5% of the worlds agricultural land while also consuming huge amounts of pesticides and herbicides. This puts enormous stress on water in dry areas, uses up valuable land that could be producing food and is extremely harmful to the environment.

Regenerative agriculture or agroecology is about working in harmony with nature using Indigenous ecological knowledge. It utilises various techniques such as crop rotation, low to no tilling, cover crops and intercropping and natural compost. These all help to draw down carbon, enhance biodiversity, enrich the soil and improve water systems. It is an ancient, nature-based solution to climate change and helps land that has become degraded to regenerate and flourish.

“Regenerative agriculture represents more than a shift of practices. It is also a shift in paradigm and in our basic relationship to nature.” Charles Eisenstein

This restorative system is being invested in by fashion brands as they work to address their environmental impacts and become climate positive rather than just carbon neutral. Some brands also use regenerative fashion to provide greater traceability with a ‘farm-to-closet’ concept in the same way the food industry has done. The idea being that customers can trace their garments back to the farm that grew the material.

View this post on Instagram

How do I Know If It’s Regenerative?

Many brands are investing heavily in land for regenerative agriculture to grow their materials, or working with companies such as Fibreshed to access materials that have been regeneratively grown. These include big names like Gucci, North Face, Eileen Fisher, Vans, Patagonia, Timberland, Stella McCartney and Reformation, in addition to small businesses like Laura’s Loom, Bristol Cloth, The Trace Collective, Rawganique, Story MFG and Solai.

“Regenerative practices are at the top of mind for many brands right now as they can offer a pathway towards addressing GHG emissions. Additionally, in some cases these practices go beyond reductions and provide a pathway for carbon sequestration” Claire Bergkamp, COO Textile Exchange

Most brands only have selective stock that has come from regenerative sources, but targets indicate this will increase over time. One certification to look out for is Regenerative Organic Certified (ROC). Regenerative fashion may also be marked as ‘Climate BeneficialTM’ which is certified by Fibreshed or it may simply just be labelled as regenerative. However, we know that fashion brands love to greenwash so always check out that their claims are substantiated and ask #WhatsInMyClothes.

Further Reading

Brands are adopting regenerative agriculture. Is that a good thing?

Regenerative Fashion: What it is + 9 brands paving the way forward

Regenerative fashion to help the planet

We are excited to announce that in May 2022, Fashion Revolution will be showcasing our very own garden at the world-famous RHS Chelsea Flower Show. Inspired by the fundamental role of plants in fashion – as dyes, fibres, floral motifs and botanical folklore – garden designer Lottie Delamain will create a textile-inspired garden solely featuring plants that can be used to make or dye our clothes.

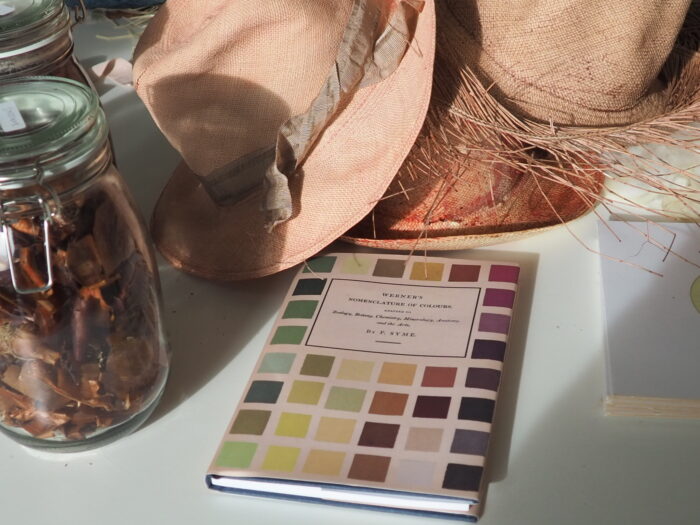

A selection of natural dye samples

The fashion industry is currently dominated by synthetic fibres and chemical dyes. Polyester manufacturing is an energy-intensive process, requiring large amounts of water and producing high levels of greenhouse gas emissions, while wastewater emitted from its processing contain volatile substances that can pose a threat to human health. Despite this, the Fashion Transparency Index 2021 found that only a quarter of major brands publish time-bound, measurable targets on reducing the use of textiles deriving from virgin fossil fuels. More than 15,000 chemicals can be used during the textile manufacturing process, from the raw materials through to dyeing and finishing, yet only 30% of brands disclose their commitment to eliminating the use of hazardous chemicals from our clothes.

Fashion Revolution co-founder Carry Somers saw the impact our clothing has on the environment first-hand two years ago, when she sailed 2000 miles into the South Pacific Gyre on an all-woman scientific research voyage to investigate microplastic pollution. Although textiles are the largest source of both primary and secondary microplastics, with around 700,000 microfibres being released in every wash cycle, just 21% of brands explain what they are doing to minimise the shedding of microfibres.

Flax seeds germinating; ingredients for making plant dyes

We believe we need a radical shift in our relationship with the clothes we wear, as well as with the natural world, for our own prosperity and wellbeing, as well as for the health of our earth and our oceans. Exhibiting these ideas within a garden provides a unique opportunity to tell the story of #WhatsInMyClothes and explore how textiles can be made in a more natural, sustainable and regenerative way. The garden allows us to reimagine the values at the essence of a new fashion system and explore how we can all start to create new relationships with our clothing.

The garden design itself is intended to imitate a textile, with planting in distinctive blocks of colour to create the impression of a woven fabric. Plants will be supplied by UK nurseries and growers and will be chosen for their use as fibres or textile dyes in commercial or craft use and the garden will feature a textile installation made entirely from plants. Shallow reflective pools represent dye baths, with fabric or fibres soaking in natural dyes, and a series of paved seams will lead through the planting.

The philosophy behind the garden is about seeing the potential in the resources we have right on our doorstep and exploring how we can utilise them in more creative ways. Many of the plants are native wildflowers, easily propagated and grown in the UK and undemanding in terms of water. This will help to re-establish the connection between plants and textiles, reveal the beauty to be found in plant-based dyes and fibres, and sow a seed of curiosity about what we wear.

The garden will be exhibited at RHS Chelsea Flower Show, taking place from 24-28 May 2022. Afterwards, the garden will be relocated to Headington School in Oxford where Kate Turnbull, Head of Fashion and Textiles Design, has developed a new syllabus which includes the study of plants used for textiles dyes and fibres, along with their propagation and use. The garden will be reimagined in two parts – as a working dye garden for the Textile Design students, and as a Colour Wheel garden, designed to inspire students across the school about the myriad roles plants play in our lives.

Stay tuned on our blog and social media for more behind-the-scenes insights as we build this inspiring new space.

Header illustration by Ben Holmes, design by Lottie Delamain