Behind the scenes: Creating our textile garden at Chelsea Flower Show

In May 2022, Fashion Revolution will be showcasing our very own garden at the world-famous RHS Chelsea Flower Show. Inspired by the fundamental role of plants in fashion – as dyes, fibres, floral motifs and botanical folklore – garden designer Lottie Delamain will create a textile-inspired garden solely featuring plants that can be used to make or dye our clothes.

Sowing the seed

The seed for the garden was actually sown years ago, while trekking in Northern Vietnam. I was living in Vietnam working as a textile designer and we used to escape Saigon at the weekends to see the rest of the country. One weekend we were on a trek near Sapa, which is up in the north near the Chinese border, an area of the country that was historically home to the H’Mong people, an ethnic group that are still living in the region. Our guide was a local H’Mong woman and we spent the nights staying with her friends and relatives along the way. Outside their homes, alongside their vegetables, they were growing indigo and hemp to make clothes, beautiful intricate textiles batiked and embroidered by generations of women.

I was so struck by the proximity they had to their clothes, the intimate understanding they had of where their clothes came from and how they were produced – a far cry from our current relationship with fashion in the modern west. (It should be noticed that this is not the only way modern H’Mong clothe themselves, but it remains an important part of their cultural heritage, rich with symbols, rituals and stories).

It was a reminder of the sophisticated ways that culture and history are communicated, and of the economic and creative resourcefulness that modern society has all but lost.

We can have any fabric, material, ink, or dye shipped directly to our door at the click of a button. We have a bottomless choice of materials from which to design and create. And we are wholly divorced from the practices, skills and methods required to grow and produce these materials.

This became the founding principle behind the garden – I wanted to challenge myself to create something using the resources we have readily available, using a restricted palette that would force a new creative approach, that explored the lost connection between plants and textiles.

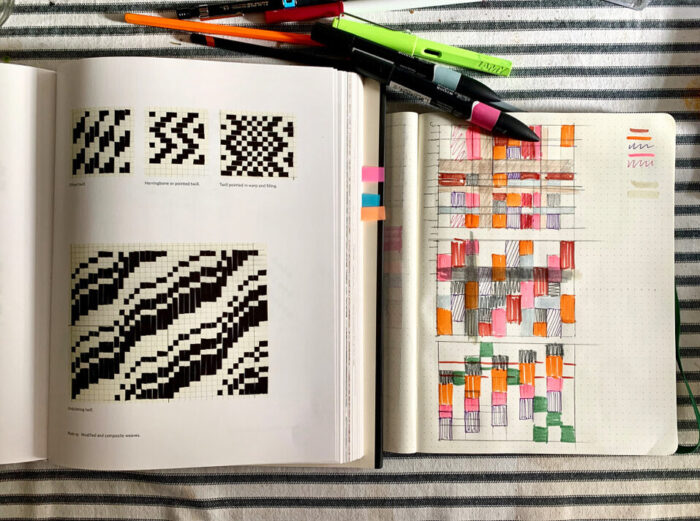

Anni Albers became my guru; her modernist principles and obsession with materials chimed perfectly with the idea. And her aesthetic (in my mind) lent itself perfectly to a garden design. I started by creating a simple weave using paper, like you did at school, following a pattern from one of Anni Albers’ books. This became the start of the geometry for my garden. I digitised it and scaled it up and used the design to mark out mass and void, putting in ribbons of paving woven through the space, large inky pools to represent dye baths and swathes of repeated colour to create the impression of a textile. I added a large-scale textile installation made from plants – linen woven from UK-grown flax, dyed using plant-based dyes, designed to make real the connection between plants and textiles.

Finding a home at Chelsea

With the garden beginning to take shape, I had to find a home for it. I began applying for show gardens, and discovered a new category at Chelsea called All About Plants. Applicants were being asked to submit ideas for gardens that put plants centre stage, along with a charity they would like to support. I immediately thought of Fashion Revolution, having worked in fashion and textiles in my previous career. Carry leapt at the idea and I knew we had hit upon a really exciting way of telling the story. Months of rigorous applications and interviews later, our garden was accepted to Chelsea and we could begin the fun of making it come to life.

Next came the plants. They had to be plants that could be used as dye or fibre, and so began an intense research process, learning about fugitive and colour-fast dyes, combing archive documents to find historic dyes, and speaking to natural dye enthusiasts up and down the country. I was determined to remain faithful to the intellectual integrity of the garden and use only plants that could be used as dye or fibre, but I needed enough of them to make the garden work and tell the story. This was all happening during the selection process for Chelsea, which meant my search was further narrowed by the timing of Chelsea and the short lead up we had to the show – sourcing unusual dye plants just wasn’t feasible in the time frame we had.

I was extremely fortunate for Kelways, the nursery that are growing all the plants for the garden. They were keen to give it a go, even though they had not grown a lot of the plants before, let alone for Chelsea, but had decades of knowledge and expertise. They are growing about 1500 plants for the garden, (alongside plants for 9 other Chelsea gardens) and have been an invaluable support throughout the process.

I am visiting them almost weekly to see the changes in growth, make small edits and begin to get a feel for what plants will be ready and looking their best for May 23rd. Lots of the plants are wild plants, not known for their ornamental value – nettle, for example, is a great fibre plant, but hard to place in a garden. Likewise, weld, which produces a beautiful strong yellow dye, is a weedy plant that is often seen in hedgerows around the UK. They are not used to being grown in pots and can be tricky to cultivate.

Bringing the garden to life

Another key part of the design was the textile installation, which is suspended above the garden on a series of lateral wires, designed to make real the connection between plants and textiles and also evoke the sense of being within a loom, with the warp and the weft. For this we have been working with Kate Turnbull, head of textiles at Headington School. Kate is a hugely knowledgeable natural dye practitioner and educator and is working with the students to bring this part of the garden to life. This has involved sampling various natural dyes to get the right combination of hues for the garden and sourcing beautiful British grown natural flax linen. After the Chelsea the garden is being relocated to the school, where I have redesigned it as a colour wheel garden and working dye garden for the students to enjoy and use.

There are so many people that have been involved in this project, it has been such a privilege to work with such talented individuals from so many different disciplines. The next few weeks will be extremely nerve-wracking as we wait to see all the different elements come together at Chelsea. At the very least, I hope it will prompt a conversation with visitors about the amazing role plants play in what we wear, and inspire them to be a bit more curious about what’s in their clothes.

Further Reading:

A Textile Garden for Fashion Revolution

#WhatsInMyClothes: The Truth Behind The Label

Nature in Freefall: How Fashion Contributes to Biodiversity Loss