En Mar del Plata, Argentina – El 30 de diciembre de 2021, el Gobierno Nacional de Argentina aprobó la instalación de petroleras en la costa atlántica bonaerense, cercanas a Mar del Plata y Necochea, generando una gran preocupación en las comunidades costeras y ambientalistas. La aprobación de este proyecto ha llevado a un estado de alerta permanente y a la convocatoria de manifestaciones en todo el país bajo la consigna #Atlanticazo por un #MarLibreDePetroleras.

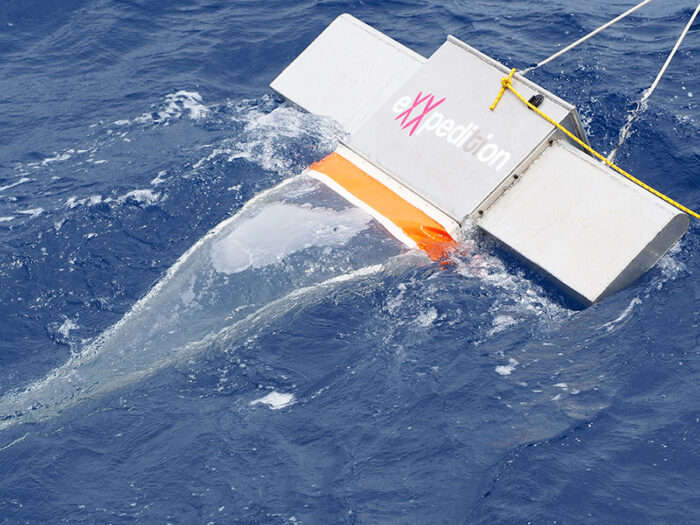

La industria petrolera se prepara para llevar a cabo la exploración sísmica en busca de hidrocarburos, un paso previo a la explotación y extracción de petróleo en aguas profundas del mar argentino. Sin embargo, este proceso se ha destacado por su alto riesgo para la vida marina y su impacto irreversible en el ecosistema marino.

La Exploración Sísmica: Un Riesgo para la Fauna Marina

La exploración sísmica involucra explosiones de radiofrecuencias muy fuertes que generan daños irreversibles y hasta la muerte de cientos de habitantes marinos. Este proceso invasivo es altamente perjudicial para la biodiversidad marina y plantea graves preocupaciones sobre el bienestar de las especies que habitan en estas aguas.

Las Plataformas Offshore y la Probabilidad de Derrames

Las plataformas offshore, utilizadas para la extracción de petróleo en alta mar, requieren de bombardeos acústicos para detectar la presencia de petróleo. Estos bombardeos, equivalentes a la explosión del despegue de un cohete, causan daños temporales o permanentes a la fauna marina y aumentan el riesgo de extinción de muchas especies. Además, estas plataformas tienen una probabilidad del 100% de derrames, lo que podría tener un impacto devastador en el ecosistema marino y en las actividades económicas de la zona, como el turismo y la pesca.

La Responsabilidad de las Empresas y el Estado Argentino

Empresas como Equinor, en acuerdo con el Ministerio de Economía, el Ministerio de Ambiente, la Secretaría de Energía y los gobiernos nacional y provincial, son responsables de este proyecto petrolero que amenaza al medio ambiente y a las comunidades costeras. Mientras que la ciencia señala la necesidad de transitar hacia un mundo sin combustibles fósiles, este proyecto va en contra de esa tendencia, convirtiendo a Argentina en una zona de sacrificio.

Contexto: Deuda externa Argentina

La deuda externa que Argentina tomó en 2017 bajo el gobierno de Mauricio Macri se ha convertido en un obstáculo crítico para la sostenibilidad financiera del país en 2023. Esta deuda, principalmente en dólares, ha llevado a la necesidad apremiante de adquirir más dólares para cumplir con los pagos, exacerbando los desafíos económicos ya existentes.

En un contexto en el que la economía argentina enfrenta fluctuaciones monetarias y una alta inflación, obtener dólares se ha vuelto cada vez más difícil y costoso. Para hacer frente a esta situación, el país se ve obligado a buscar financiamiento adicional, lo que tiene un impacto negativo en la economía y en la calidad de vida de la población.

La Resistencia: #Atlanticazo

Ante esta amenaza, la Red de Comunidades Costeras ha convocado a la resistencia bajo la iniciativa #Atlanticazo. Se denuncia al Estado Argentino, a las empresas petroleras y a los medios de comunicación hegemónicos que promueven este proyecto ecocida. La resistencia busca evitar la destrucción del ecosistema marino y proteger los bienes comunes de la costa atlántica.

El 4 de octubre de 2023, se llevarán a cabo manifestaciones en diversas ciudades de Argentina y del mundo bajo el lema “Petroleras en el mar NO PASARÁN”. Las comunidades costeras y los defensores del medio ambiente continúan luchando para preservar el mar argentino y garantizar su sostenibilidad.

La lucha por un #MarLibreDePetroleras es un llamado urgente a la acción, no solo para proteger el ecosistema marino, sino también para promover un futuro más sostenible y respetuoso con el planeta. La transición hacia energías limpias y la preservación de nuestros océanos son desafíos clave para construir un mundo más justo y equitativo.

El llamado es claro: el mar argentino está en peligro, y es responsabilidad de todos tomar medidas para protegerlo y garantizar su supervivencia para las generaciones futuras. La lucha continúa, y la resistencia se fortalece en defensa de nuestro mar y nuestro planeta.

Cronograma del #ATLANTICAZO en ARGENTINA – Miércoles 4 de Octubre:

- SAN ANTONIO OESTE: Los Tamariscos en defensa del mar junto a Vuela el Pez Infancias + naturaleza + arte 8:30 hs.

- POSADAS: Plaza 9 de Julio 9 hs.

- NECOCHEA: Puente Colgante 11 hs.

- MENDOZA: Portones del Parque 12 hs.

- LA PLATA: Plaza Moreno a Plaza San Martín 16 hs.

- RIO GRANDE: Plaza Almirante Brown 16:30 hs.

- MAR DEL PLATA: La Rambla 17 hs.

- CABA: De Congreso a Casa de la Provincia de Bs.As. 17 hs.

- PARANÁ: Plaza Alvear 17 hs.

- USHUAIA: Cartel de Ushuaia 17hs. Movilización al puerto a las 17:30hs.

- BAHÍA BLANCA: U.N del Sur, 12 de Octubre y San Juan 17:30 hs.

- PUERTO MADRYN: Fuente de la Rambla 18 hs.

#Atlanticazo en el mundo:

Noruega, España, Holanda, Indonesia, Venezuela, Colombia, México, Ecuador, Brasil, Bolivia, Uruguay, Paraguay y Sudáfrica.

Para más información dirígete AQUÍ

Información en tiempo real en @marlibredepetroleras

La dependencia de la moda a los combustibles fósiles

La moda y los combustibles fósiles están más conectados de lo que podríamos imaginar. La industria de la moda, que abarca desde la producción de textiles hasta la confección de prendas y su comercialización, depende en gran medida de los combustibles fósiles en cada etapa de su ciclo de vida.

- Producción de textiles: La fabricación de fibras sintéticas como el poliéster, el nylon y el acrílico, ampliamente utilizadas en la moda, se basa en la petroquímica, que utiliza petróleo crudo como materia prima. Estas fibras representan una parte significativa de la producción de textiles.

- Procesamiento y teñido: El procesamiento y el teñido de textiles también son intensivos en energía y dependen en gran medida de los combustibles fósiles para alimentar las máquinas y generar calor en los procesos.

- Transporte y logística: La moda es una industria global, lo que significa que la ropa a menudo viaja miles de kilómetros antes de llegar a los estantes de las tiendas. El transporte de materias primas, productos semielaborados y prendas terminadas consume grandes cantidades de energía fósil.

- Comercialización: Las campañas de marketing y publicidad, así como el funcionamiento de las tiendas físicas y en línea, también dependen de la energía derivada de los combustibles fósiles.

Lo que trae como consecuencia:

- Impacto ambiental: La producción de ropa es una de las principales fuentes de contaminación del agua y emisiones de carbono en todo el mundo. La extracción de petróleo para materiales sintéticos y el transporte de prendas a larga distancia contribuyen significativamente a la huella de carbono de la moda.

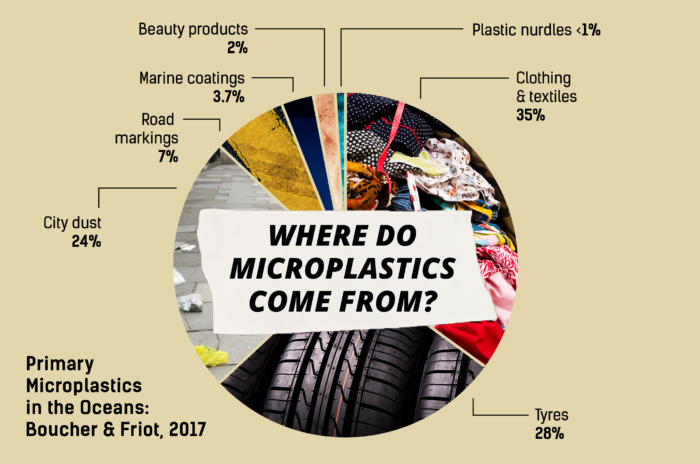

- Microplásticos: La mayoría de la ropa fabricada con materiales sintéticos libera microplásticos en los océanos cada vez que se lava. Estos microplásticos provienen de fibras de plástico que son derivadas del petróleo.

Este vínculo entre la moda y los combustibles fósiles tiene importantes implicaciones ambientales. La extracción y producción de petróleo crudo y gas natural generan emisiones de gases de efecto invernadero, contribuyendo al cambio climático. Además, la moda rápida, caracterizada por la producción y el descarte rápidos de prendas, agudiza el problema al aumentar la demanda de textiles sintéticos y promover un ciclo de consumo insostenible.

Para abordar esta problemática, la industria de la moda está empezando a explorar alternativas sostenibles, como la producción de textiles a partir de materiales reciclados o renovables y la adopción de prácticas más ecoamigables en la cadena de suministro. La conciencia sobre la necesidad de reducir la dependencia de los combustibles fósiles en la moda está creciendo, y los ciudadanos también están desempeñando un papel crucial al optar por marcas y prendas libres de petróleo.

La relación entre la industria de la moda y los combustibles fósiles en cifras

- Consumo energético: La industria de la moda es responsable del 8% del consumo energético global, siendo una de las mayores consumidoras de energía entre los sectores industriales. Gran parte de esta energía proviene de fuentes de combustibles fósiles.

- Emisiones de carbono: La moda contribuye al 10% de las emisiones globales de carbono, lo que la convierte en una de las industrias más contaminantes, incluso superando a la industria aérea y marítima combinadas.

- Producción de fibras sintéticas: La producción de fibras sintéticas, como el poliéster y el nylon, que provienen del petróleo, representa aproximadamente el 65% de todos los materiales utilizados en la industria de la moda.

- Transporte: El transporte de productos de moda a nivel internacional requiere una cantidad significativa de combustibles fósiles. En 2019, se estimó que la industria de la moda emitió alrededor de 1.400 millones de toneladas de dióxido de carbono debido al transporte.

- Desperdicio: Cada año, se producen alrededor de 92 millones de toneladas de desperdicios textiles, y gran parte de estos desperdicios son incinerados o enviados a vertederos, liberando dióxido de carbono a la atmósfera.

- Microplásticos: Se estima que el lavado de prendas de materiales sintéticos libera hasta 500.000 toneladas de microplásticos en los océanos cada año, además la ropa y los textiles son la fuente número 1 de microplásticos en los océanos, siendo el 34,8% del total global, lo que agrava aún más el problema de la contaminación por plásticos.

Estas cifras muestran la magnitud del impacto ambiental de la industria de la moda en términos de consumo de energía, emisiones de carbono y contaminación por microplásticos, todos los cuales están relacionados con la dependencia de los combustibles fósiles. Es esencial abordar estos problemas para lograr una moda limpia y reducir su huella ecológica.

Por estas razones te invito a revisar las etiquetas de composición de tus prendas y pregunta a las marcas #QUEHAYENMIROPA

Fuentes:

Red de Comunidades Costeras a través de la Coordinadora @bastadefalsassoluciones

¨Historia de la deuda externa Argentina¨ Wikipedia en Español

Fashion Revolution Week is our annual campaign bringing together the world’s largest fashion activism movement for seven days of action. It centres around the anniversary of the Rana Plaza factory collapse, which killed around 1,138 people and injured many more on 24 April 2013.

This year, as we marked the tenth anniversary of the Rana Plaza factory collapse, we remembered the victims, survivors and families affected by this preventable tragedy and continue to demand that no one dies for our fashion. To define the next decade of change, we translated our 10-point Manifesto into action for a safe, just and transparent global fashion industry. Our campaign platformed the work of our diverse Global Network who provided local interpretations of their chosen Manifesto point(s). We believe that while fashion has a colossal negative impact, it also has the power and the potential to be a force for change. Together, we expanded the horizons of what fashion could – and should – be.

Here, catch up on some of the week’s highlights and find out how to stay involved with our work, all year round.

Remembering Rana Plaza

Fashion Revolution Week happens every year in the week coinciding with April 24th, the anniversary of the Rana Plaza disaster. On April 24th 2013, the Rana Plaza factory building in Bangladesh collapsed in a preventable tragedy. More than 1,100 people died and another 2,500 were injured, making it the fourth largest industrial disaster in history. On April 24th, we paused all other campaigning to pay our respects to the victims, survivors and families affected by this tragedy, and came together as a global community to remember Rana Plaza.

As we reflect a decade on, we are inspired by and celebrate the progress made in the Bangladesh Ready-made Garment (RMG) sector by the Accord. The International Accord on Fire and Building Safety was the first legally-binding brand agreement on worker health and safety in the fashion industry and is the most important agreement to keep garment workers safe to date. This year, we pay tribute to the joint efforts of all Accord stakeholders who have significantly contributed to safer workplaces for over 2 million garment factory workers in Bangladesh, including the Bangladeshi trade unions representing garment workers, alongside Global Union Federations and labour rights groups. We welcome the introduction of the Pakistan Accord and would like to see the adoption and success of the International Accord replicated in all garment producing countries.

Manifesto for a Fashion Revolution

Our theme for Fashion Revolution Week 2023 was Manifesto for a Fashion Revolution. Back in 2018, we created a 10-point Manifesto that solidifies our vision to a global fashion industry that conserves and restores the environment and values people over growth and profit. This year we called on citizens, brands and makers alike to sign their name in support of turning these demands into a reality, boosting our signature count to 15,500 Fashion Revolutionaries and counting. We are immensely grateful to everyone who has and continues to sign; our power is in our number and each signature strengthens our collective call to revolutionise the fashion industry.

To campaign for systemic change in the fashion industry, we themed the week around complementary Manifesto points, providing ways to be curious, find out and do something daily around each of them. From supply chain transparency to living wages, textile waste to cultural appropriation, freedom of association to biodiversity, we shared global perspectives and solutions to fashion’s most pressing social and environmental problems.

Over the past ten years, the noise around sustainable fashion has only got louder. But meanwhile, real progress is too slow in the context of the climate crisis and rising social injustice. That’s why Fashion Revolution Week 2023 was an action-packed and future-focused campaign that amplified the actions and perspectives of Fashion Revolutionaries around the world.

View this post on Instagram

Global Conversations

To capture these global perspectives, we launched the Fashion Revolution Map on Earth Day, which coincided with the start of Fashion Revolution Week. Developed by Talk Climate Change, the Map served as a global forum to reflect on the week’s themes and events, using our Manifesto as a talking point. Fashion Revolutionaries continued the discussion offline by inviting their family, friends, colleagues and classmates to imagine what a clean, safe, fair, transparent and accountable fashion industry would look like with us. These conversations were then recorded on the Map as a source of inspiration and knowledge exchange.

Anyone can be a Fashion Revolutionary; it starts with a simple dialogue about the changes you want to see in the fashion industry. Make your voice heard by contributing to our map today and help change the fashion industry through the power of conversation!

View this post on Instagram

Good Clothes, Fair Pay Highlights

Ten years on from Rana Plaza, poverty wages remain endemic to the global garment industry. Most of the people who make our clothes still earn poverty wages while fashion brands continue to turn huge profits. At Fashion Revolution, we believe there is no sustainable fashion without fair pay which is why we launched Good Clothes, Fair Pay as part of a wider coalition last July. The Good Clothes Fair Pay campaign demands living wage legislation at EU level for garment workers worldwide, building on Manifesto points 1 and 2.

During Fashion Revolution Week, our EU teams coordinated awareness events, campaigns and marches to mobilise signatures for this campaign. On April 25th, we headed to the European Parliament with Fashion Revolution Belgium to demand better legislation in the fashion industry. The day of action consisted of a panel discussion between Members of the European Parliament and impacted fashion stakeholders, and ended with a stunt outside the Parliament. Fashionably Late highlighted that the EU is running out of time to act on poverty wages in fashion. This stunt was replicated by our teams in Germany, France and the Netherlands throughout Fashion Revolution Week to demonstrate EU-wide solidarity with the people who make our clothes.

We have less than three months left to collect 1 million signatures from EU citizens to push for legislation that requires companies to conduct living wage due diligence in their supply chains, irrespective of where their clothes are made. If you are an EU citizen, sign your name here. If you’re unable to sign, please support the campaign by sharing it far and wide online.

View this post on Instagram

Fashion Revolution Open Studios Highlights

Fashion Revolution Open Studios is Fashion Revolution’s showcasing and mentoring initiative since 2017. Through exhibitions, presentations, talks, and workshops with emerging designers, established trailblazers and major players, we celebrate the people, products and processes behind our clothes.

This Fashion Revolution Week, Fashion Revolution Open Studios joined forces with Small but Perfect to spotlight the work of 28 European SMEs taking part in their circularity accelerator project. Forming part of this European events programme, Fashion Revolution Open Studios held a two-day event in partnership with The Sustainable Angle and xyz.exchange at The Lab E20. The event showcased seven innovative designers from the Small But Perfect cohort of sustainable SMEs and displayed how they are embedding circular solutions into their work, from crafting grape leather handbags to developing community approaches to making and working together. Alongside the exhibition, there were livestreamed webinars, workshops and panel discussions to explore the projects and hear about some of the the challenges facing small businesses and the industry at large in switching to circular business models.

Global Network Highlights

With 75+ teams from all around the world, Fashion Revolution Week 2023 championed the perspectives and contributions of our Global Network. Here are just a small selection of highlights from our country teams:

Fashion Revolution New Zealand unpacked each Manifesto point with industry trailblazers in an Instagram Live series.

Fashion Revolution teams in Bangladesh and Sweden co-organised a virtual panel discussion on shifting consumer behaviour.

Fashion Revolution Singapore celebrated the launch of their digital zine MANIFESTO.

Fashion Revolution teams in Iran and Germany collaborated on Women, Life, Freedom, a joint exhibition.

Fashion Revolution Nigeria shared the stories and journeys of local slow fashion brands.

Fashion Revolution Argentina invited us to join their Wikipedia edit-a-thon.

Fashion Revolution teams in Vietnam, South Africa and Scotland hosted local community clothing swaps.

Fashion Revolution India won the Elle Sustainability Award for Eco-Innovation in Fashion.

Fashion Revolution Uganda brought together the country’s top designers and brands at Kwetu Kwanza.

Fashion Revolution teams in UAE and Canada both held local design competitions for students.

Fashion Revolution Hungary championed the revival of traditional folklore practices in clothing and fashion.

Fashion Revolution USA discussed the fashion industry’s impact on people and planet in a 2-part Zoom series.

Fashion Revolution Uruguay hosted Fashion Celebrates Life, a community picnic themed around Manifesto point 10.

Fashion Revolution teams in Chile and Portugal shared their Fashion Revolution Week highlights with us on Instagram Live.

You are Fashion Revolution

We are so grateful to everyone in our community for getting involved in Fashion Revolution Week on social media and beyond. Every single voice makes a difference in our fight for a fashion industry that conserves and restores the environment and values people over growth and profit.

While Fashion Revolution Week 2023 may be over, our community, our campaigning and our movement continues, 365 days a year. Please join us in fighting for systemic change by:

Following us on social media: Stay up-to-date by following us on Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, LinkedIn and YouTube, and signing up to our weekly newsletter.

Finding your country team: Connect with the teams in your region by following them online, attending their events and volunteering with them. Find your country team here.

Using our online resources: Our website is a treasure trove of information, from how to guides and online courses to annual reporting on transparency on the fashion industry. Get started here.

From all of us in the Fashion Revolution team, we appreciate your support and we look forward to seeing you next year!

In Addis Ababa, Amharic language filled its bustling crowded streets. The city’s smoggy air and high altitude of 2600m contributed to our difficult adjustment to limited oxygen. It was mid-May 2022, when we, a team of researchers from Drip by Drip, started our five week exploration of Ethiopia, “the rising star” in textile production.

Drip by Drip is a German-based nonprofit organisation that exists to tackle water pollution through the textile industry. Currently, we are working in Bangladesh on two different projects. For the future, we want to extend our impact into more countries that suffer from decreasing clean water resources, which led us to Ethiopia.

We set out to understand the current situation of Ethiopia’s textile and garment industry. In doing so, it was our goal to learn about the current political and economic situation and to understand whether Ethiopia will be the next Bangladesh. Additionally, through a three-week collaboration with Sequa gGmbH, an NGO funded by GIZ (German society for international cooperation) and UKAID, we had the opportunity to visit local factories, the Hawassa Industrial Park, and speak with a large international buying agency, which acts as a liaison between major brands and production facilities. We also conducted interviews with stakeholders, which included local and foreign factory managers, factory employees, NGOs, B2B customers, ministry staff, and entrepreneurs. To protect the identity of the interviewees we will not disclose their names.

The Rising Star

Our preliminary research depicted Ethiopia as a budding force in textiles, with the potential of competing against China’s and Bangladesh’s industry. However, we quickly discovered the lack of validity and substantiality in our online sources. The lack of data brought up questions about Ethiopia’s labor costs, work environment, industrial waste, access to water, infrastructure, investments, foreign connection, the security and health system.

In 2020, the Economic Intelligence Unit, predicted an economic growth in Ethiopia of 7% .(1) In comparison to other African countries, whose common growth rate ranged from 2%to 3%, Ethiopia appeared to be advancing faster. Additionally, the International Monetary Fund predicts an increase in their gross domestic product (GDP) from 3.84% in 2022 to 5.72% in 2023, 6.23% in 2024, and so on.(2) On top of this, Ethiopia has a population of roughly 110 million people, with an expected growth rate of 2.49%.(3) A country with an exponentially growing population offering a plethora of job opportunities with no legal framework of a legal minimum wage is an attractive option for investors. Because: A growing population ensures investors a growing workforce. Additionally, Ethiopia offers low labor costs. Where there is a low labor cost, you will commonly find textile and garment businesses. The average pay wage for garment workers range from $340 to $95 per month, while in Ethiopia, the pay wage is set at $26 per month.(4) This causes a slow and silent factory shift from China, Vietnam and Bangladesh to countries like Ethiopia. Last but not least, the war that began in the Tigray region in the north of the country about a year ago and has spread to more southern regions.(5), is having a destabilising effect on the entire country.

Ethiopia’s Export and Import Dilemma

To investigate further, we scheduled meetings for the first two weeks of our exploration with stakeholders in the field of environmental science, textile production, and business management. Stakeholders included locals, professors, consultants, activists, businesspeople, and fashion designers. Our preliminary research depicted Ethiopia on the cusps of a new era as they transitioned from a developing state to an industrial state, but it became evident that we drastically underestimated the situation. With every conversation, the illusion of the “rising star in the textile industry” vanished. Under former Prime Minister Zenawi Haile, the Ethiopian government pursued a Growth and Transformation Plan, which expired in 2020. This plan pursued various targets, one of which was the development of industry. Under these targets, 13 industrial parks were established for different manufacturing industries – the textile and garment industry were one of them.

Industrial parks (IPs) are portions of a city zoned for industrial use. Through the construction and promotion of IPs, Ethiopia approached investors and companies to establish themselves at industrial parks; unfortunately, with no long-term success. We learned from an Indian-owned garment company that their production capacity has shrunk by 50%. Adding to the dilemma, the US terminated the AGOA agreement, which forced the closure of many factories. The African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) is a US agreement that allows AGOA member countries to export duty – free and tax – free to the United States. Ethiopia has long been a member, but in November 2022, Biden terminated that alliance on the grounds that Ethiopia harbors “violations of international human rights.” Such termination caused major producers and fashion companies, such as the PVH Group, to halt production in Ethiopia. With AGOA, companies exported 60% – 80% of their goods. Since its termination, exports have shrunk to 20% – 30%, along with a decrease in the country’s number of textile companies. We visited the industrial park in Hawassa, the largest IP hosting 52 halls that are now mostly empty due to the AGOA termination. Hawassa’s IP stood as a foreshadow or a glimpse into the future for many foreign investors, especially from India, China, Bangladesh and the US.

During AGOA, a majority of Ethiopia’s goods were exported to the US. Now that AGOA has ended, factory owners want to focus on the EU market. The EU is a more complicated venture though, as it has more regulations and requirements than the US, such as certifications like CmiA, OEKO-TEX Standard 100 and SteP or the BSCI. For Ethiopian textile companies, this would mean a new type of commitment.

Exporting and Importing with an Ethiopian-Owned Factory

We often came across non-certified Chinese, Indian or Sri Lankan operated factories that usually import their cotton from China or India. Fortunately, we were able to visit an Ethiopian – owned textile production site located in Kombolcha, about an hour flight from Addis. Kombolcha Textile Share Company is a 100% Ethiopian operated factory that uses 100% Ethiopian cotton and has a water treatment plant. The factory is also OEKO TEX SteP and ISO 14001:2015 and ISO 9001:2015 certified – a real rarity in the Ethiopian market. The factory owner of Kombolcha Textile informed us about his problems with importing chemicals, dyes, or spare parts for machines. Since Kombolcha Textile is a certified company, he is obliged to use certified chemicals, but Ethiopia does not produce those. In the past, he purchased his dyes from a Swiss company that had stores in Ethiopia. Unfortunately, the Swiss company closed its stores, which means the factory owner must now import all those goods. To pay for and import goods from abroad, an Ethiopian company needs foreign exchange (forex). Foreign exchange is one of the biggest challenges of the industry. Unlike Euro (EUR) or US Dollar (USD), Ethiopian Birr (ETB) is not an official trading currency.

We learned about Ethiopia’s foreign exchange issue from a GIZ employee. To understand the following example, let’s define two terms:

● Export turnover is the sale proceeds or a company’s earnings from their exported goods.

● Foreign exchange (forex) is trading one currency for another.

So, if an Ethiopian company’s export turnover, or earning amount, is 100 EUR. 80% of their earnings will be converted to ETB and 20% will be converted to forex. This leaves them with 80 ETB and 20 EUR. Then, 80% of that 20 EUR must be given to the Ethiopian government for forex taxes. This means that the company has only 4 EUR remaining. Remember, ETB is not an official trading currency and they are not allowed to convert the 80 ETB to EUR or USD. Therefore, the company can only use the remaining 4 EUR to import goods. Needless to say that 4 EUR is not enough to import goods from abroad. Therefore, the instability of import and export costs makes it nearly impossible for smaller companies to survive, especially when they rely on a small amount of forex.

On top of this, the cost of homegrown cotton increased significantly in Ethiopia. In comparison, the Indian cotton price is 2.10 USD, which is about 109 ETB per kg, and the Ethiopian cotton price is 130 to 150 ETB and rising. As a result, many small local factories, like Kombolcha Textile, now use their own stock of cotton for production, which will only last for another 6 months. Overall, we discovered that the priorities of the industry are on one hand export growth and on the other hand employment growth. When it comes to water management, a very complex issue, there is a lack of focus on water supply and sanitation for both large industries and local manufacturers, which led us to the next challenge.

The Water Problem

We had the pleasure of speaking with professors from a highly renowned university in Ethiopia. They shared with us Ethiopia’s rich water history that gave the country its nickname – the “Water Tower” of Africa. A local friend informed us about Ethiopia’s government-supervised water meters for private households. These meters are read monthly and consumption must be paid accordingly. Unfortunately, this is not the case for industries. Through a conversation with a consultant from an Environmental Consultancy Service, that proposes for environmental reform to the Ministry of Industry as well as the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, we learned the following about industrial water consumption:

IPs are built by the government, and foreign investors rent out the space and use it for production. Foreign investors pay for rent and electricity, but water is free. They are allowed to drill their own water boreholes and are not required to prove consumption. Additionally, treatment of wastewater is recommended, but not required for production. Therefore the consultancy company advocates for more regulations surrounding wastewater decontamination and water extraction.

An employee from an Indian – owned textile company spoke with us about their wastewater system and treatment plant. They installed their wastewater treatment plant a year after the company opened. It is designed to treat chemicals and dyes so that the wastewater can be recycled back into the company’s water cycle. However, the plant did not have the capacity to treat the amount of wastewater produced. So, up until 2 years ago, production simply discharged their excess wastewater, especially in the rainy season, to the surrounding fields. Farmers from the surrounding areas rightfully complained about the issue, and the government gave the company a warning. Since then, wastewater has not been discharged, but no solutions about the contaminated fields, which still release an acrid smell, have been discussed. Then, another issue came up. It was further explained that when the water goes back into production to be reused, 10% is left as compressed sludge residue in the form of granules. The company produces 5 bags of granules per day. These bags were simply disposed of in surrounding areas. The government then required the company to store the bags, which are now kept in a warehouse onsite, but there is no solution for its final disposal.

Conclusion

Without the warmth and hospitality of the Ethiopian people, we would not have been able to learn anything about textile production. The biggest challenge for us was the access to data, because especially in the area of water there are almost no reliable surveys. So the personal conversations with the different stakeholders were essential for our assessment. Ethiopia clearly has the potential to become the next “rising star” in the textile industry. However, the political and economic challenges are still too great at the moment. Therefore, we leave the country with mixed feelings. Ecologically, it remains to be feared that the uncontrolled water extraction by the industries, as well as the growing interest in local cotton cultivation, will lead to a significant shortage of clean groundwater. For the economic situation of the unemployed population, on the other hand, the IPs could be a long-awaited blessing. Similar to Bangladesh, positive effects on the emancipation of women can also be expected. A dichotomy that can be resolved: An early enactment of laws regulating the use of water as a resource throughout the production cycle. Because without clean water, even the greatest economic boom cannot prevent another humanitarian crisis. We will continue to follow the developments with great interest.

A report by Charlotte Kühl & Michelle Dixon for Drip by Drip

Charlotte Kühl is a student for clothing technology and fabric processing. During her involvement with Drip by Drip as a working student, she went on a seven-week research trip to Ethiopia, to analyse the status quo of the textile and apparel industry. This article is a summary of her findings.

Michelle Dixon is a writer and visual artist with an interest in fashion and water pollution. She holds a Master of Arts in Nature – Culture – Sustainability Studies and her research encompasses fashion and agriculture, fashion and water security, and fashion and grace. She is a researcher and project assistant at Drip by Drip.

The copyright for the pictures belongs to Charlotte Kühl.

Further reading

Fashion’s opportunity to be a force for good

Fashion’s role in fighting human trafficking, reducing vulnerability, and uplifting humanity

Beyond Compliance in the Garment Industry

Ecocide.

Few words hold as much power as this one. Ecocide comes from the Greek oikos, which means home; and the Latin occidere, which means to kill. To kill our common home: that is the literal meaning of this mysterious word.

View this post on Instagram

Legally, ecocide is defined as the most serious crimes against the environment. To be more specific, an International panel of experts, initiated by Stop Ecocide International, defined ecocide as “unlawful or wanton acts, committed with knowledge that there is a substantial likelihood of severe and either widespread or long-term damage to the environment being caused by those acts”.

In concrete terms, what are we talking about? Recurring oil spills, the ongoing mass deforestation of the Earth’s primary forests, the emission by only 100 companies of 71% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions between 1988 and 2015…

These ecocides are the reason for the current ecological and climate crisis. They endanger our capacity to live on this Earth. Yet, to this day, they remain unpunished. Criminal law at the international level, or in most national law, simply does not recognise the crime of ecocide, and lets the people responsible for them free of any accountability.

This is what a 50 years old movement of activists, lawyers and elected representatives from all around the world is trying to change, and the mobilisation is growing! More and more countries, or their parliaments, are supporting the recognition of the crime of ecocide. Citizens are rising to ask political leaders to act to put an end to these crimes and protect the environment and our human rights.

Today, on March 20 2022, citizens all around Europe, in Brussels, Paris, Rome, Amsterdam and Madrid, and around the world are mobilising to ask for the recognition of ecocide in the European Union and at the international level.

What does it have to do with fashion? Well, everything, because recognising ecocide will make companies from all sectors change their behaviour to better take into account the environment.

We know that the fashion industry is a massive polluter. It is the third sector that consumes the most water in the world. It emits every year 1.2 billion tonnes of greenhouse gas, about 10% of the world’s emissions. 500 000 tonnes of microplastics are thrown in the ocean each year due to the production of clothes. And as usual, what endangers the environment also endangers humans: 60 million women textile workers worldwide are exposed to hazardous and toxic chemicals, including pesticides, on a daily basis.

In Bangladesh, rivers are turning black due to the sludge and sewage produced by textile dyeing and processing factories. In Chile, 39,000 tonnes of clothing waste are being stocked in the Atacama desert.

Recognising ecocide and all environmental crimes in law will enable us to prevent these crimes before they happen. It will force companies to change their behaviour, in order not to face criminal sanctions.

Recognising ecocide also means recognising that the destruction of the Earth is one of the most serious crimes, and cannot be ignored anymore. The symbolic power of such recognition should not be underestimated.

As the European Union is currently working on revising its environmental criminal law, I will work tirelessly to include the recognition of ecocide in the text. If you want to support this fight, sign the European petition and share your support on social media with the hashtag #StopEcocideEverywhere.

Together, let’s put an end to ecocide.

Related articles

Fashion brands’ leather sourcing practices are driving deforestation

Fashion unites on a call to action for COP26

Further reading on ecocide

- What is ecocide?

- Making ecocide a crime

- Ecocide: Should killing nature be a crime?

- How a global ecocide law could hold polluters to account

La contaminación por tintes es uno de los problemas de la industria textil que amenaza el planeta y nuestro bienestar. Utilizamos el agua como si fuera un recurso inagotable pero la verdad es que solo un 3,5% aproximadamente de toda el agua de la Tierra es dulce y está apto para el consumo. El uso intensivo de la tierra, la deforestación, el cambio climático y el mayor consumo de agua dulce por una población y una industria que no dejan de crecer amenazan nuestros ríos, lagos y los depósitos bajo tierra.

La triste história del río Yangtze

En china, más del 80% de toda el agua subterránea está tan contaminada que no puede destinarse ni para usos agrícolas. En el sudeste de dicho país el 70% del agua contaminada es responsabilidad de las industrias textiles de la zona.

El río Yangtze es conocido como el río más largo de China y recibe el 40% del desecho industrial y textil de todo el país. Cada año se lanzan allí más de 25 millones de toneladas de desechos, según la WWF. La industria textil posee vertidos con una alta carga tóxica, provocada por muchos metales como el arsénico o el cadmio, que pueden provocar una mortalidad del 100% a las especies marinas.

El problema de la salubridad ya no solo se encuentra en las ciudades más cercanas del río Yangtze, sino que las zonas más alejadas empiezan a tener problemas con la contaminación. La liberación descontrolada de químicos y tintes ha llegado a modificar el color del agua, donde son normales las mareas rojas, negras o incluso azules.

Río Azul

Para entender la complejidad del problema causado por la contaminación por tintes en las ciudades más importantes en fabricación de tejidos, podemos embarcar en un viaje con el documental River Blue y descubrir la realidad que se encuentra detrás de cada etiqueta. Una rápida pero impactante imagen que nos enseña la realidad de muchos procesos y como actualmente somos capaces de cambiar nuestro impacto en el agua.

Una alternativa: los tintes naturales

Comprendemos la importancia de los colores en nuestras prendas y sabemos que son parte intrínseca y fundamental del proceso de diseño. Por eso, es importante buscar alternativas que no dañen el medioambiente ni nuestra salud. Incluso, el pasado nos puede ayudar en esta búsqueda: hay evidencias arqueológicas de que se han utilizado colorantes textiles desde el periodo Neolítico.

Los tintes naturales son colorantes que se extraen de plantas, insectos y minerales y que tienen la calidad de teñir fibras naturales, tales como: algodón, yute, lana, cáñamo, seda, etc.

Algunas técnicas artesanales de tinte natural

#Ecoprint: una técnica de estampación natural con hojas frescas.

#BundleDye: una técnica contemporánea de estampación natural en que se utiliza el vapor para transferir materiales vegetales sobre la tela.

#Shibori: una técnica tradicional japonesa de teñido. El diseño se consigue moldeando un trozo de tela, creando zonas de reserva y teniéndolo.

Una ayuda de la tecnología

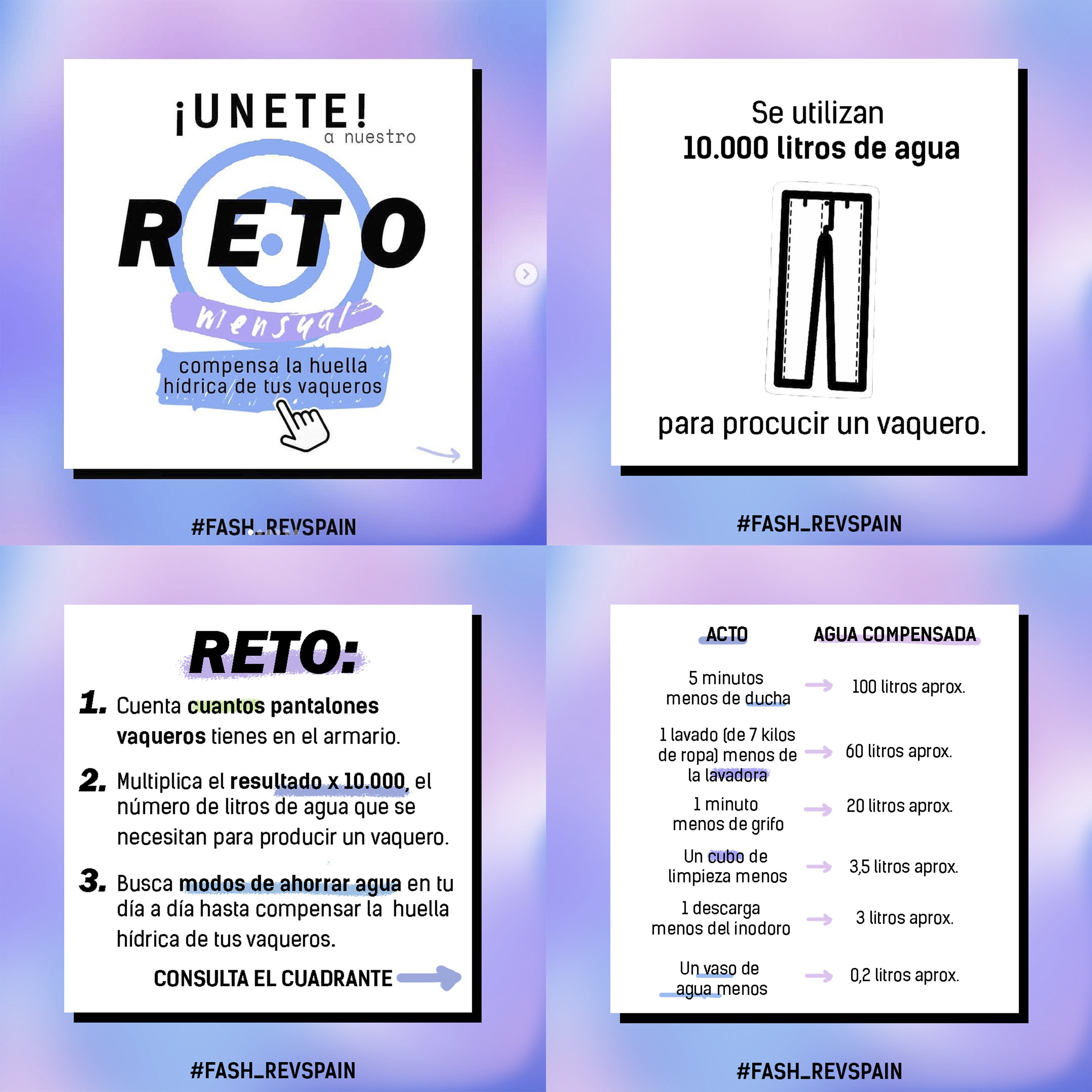

Además de los tintes naturales, la tecnología también nos puede ayudar a disminuir los impactos de la industria textil en la contaminación por tintes. Por ejemplo, ahora ya es posible producir unos tejanos utilizando un 71% menos del agua gracias a la investigación de empresas como Jeanologia. Acabados hechos con tecnología láser o Ozono pueden contribuir para la reducción de la huella hídrica de la industria textil.

Entonces, ¿qué puedo hacer?

La huella hídrica de un español promedio es de 6,700 L de agua al día, el equivalente a 42 barriles llenos de agua. Eso sucede en un mundo donde al día de hoy, más de 1,000 millones de personas no tienen acceso a agua potable, mientras que 2,600 millones carecen de saneamiento adecuado. Por eso, intentar reducir nuestro impacto es un reto importante y necesario. Durante el mes de marzo, animamos a nuestros seguidores en Instagram a compensar la huella hídrica de sus vaqueros. ¿Te animas?

Acuérdate de que reducir el consumo y comprar de forma más concienciada también son acciones importantes para reducir nuestros impactos en la contaminación del agua. Todo aquello que compramos tiene una huella hídrica que es la cantidad de agua necesaria para que un producto llegue a nuestras manos. Ser conscientes de eso es fundamental para tomar decisiones que hagan de nuestro planeta un lugar más sostenible.

#QuéHayEnMisColores

También puedes unirte a nuestra campaña en redes sociales compartiendo un selfie enseñando la etiqueta de tu prenda de ropa con el cartel ¿Qué hay en mi ropa?, compartirla en las redes sociales con los hashtags #QueHayEnMisColores, #quehayenmiropa y etiquetándonos: @fash_revspain.

Parar y revertir los impactos de la contaminación del agua por tintes es un compromiso con el futuro del planeta y el bienestar de la humanidad. Nuestra contribución individual es importante, pero no debemos olvidar que el cambio de la industria textil es esencial para que podamos empezar una ruta más justa y sostenible.

Fashion Revolution Week is the time when we come together as a global community to create a better fashion industry. It centers around the anniversary of the Rana Plaza factory collapse, which killed 1,138 people and injured many more on April 24, 2013.

This year, as we marked eight years since the tragedy, Fashion Revolution Week focused on the interconnectedness of human rights and the rights of nature. Our campaign in the USA amplified unheard voices across the fashion supply chain and harnessed the creativity of our community to explore innovative and interconnected solutions.

Below, get a glimpse at our over 20 events bringing together 67 makers, doers, and changemakers within the field, delving into topics of land, water and air; ownership; workers; nature; gender; education; and what we can all do to be moved toward action for a better fashion future. As well, our volunteer network of Regional Coordinators, City Leads, and Student Ambassadors brought the fashion revolution to life in new and unique ways in their communities, helping the movement grow throughout the United States.

Monday, April 19: Land, Air, and Water

Hashtag Revolt: Through our global coordinated effort to infiltrate the #hashtags of many #fastfashion brands, the #hashtagrevolt campaign attracted over 500 posts across social media channels. We’re grateful to our partner organizations and industry leaders that helped us to reach citizens outside of the sustainable fashion echo chamber, including @Greenpeace, @FairTradeCertified (our co-branded partner!), @chicksforclimate, @ecoage, @canopyplanet, @marinatestino, @amandahearst, @stand.earth, What the Hack (who launched a hack-a-thon to amplify these efforts) and many others! Fashion Revolution USA’s messaging successfully disrupted the fast fashion brands’ hashtag feeds on April 19th, sparking international curiosity among concerned citizens.

Environmental Racism and the Fashion Industry: Laura Diez from Ecochic Podcast helped us tackle the topic of #EnvironmentalRacism in the fashion industry and how it shows up in the USA. With race being the top predictor of a person living near contaminated soil, air, or water; she described some of the environmental injustices that occur in BIPOC communities, in practice and policy. She covered racism, redlining, Superfund sites, and what legal tools exist to combat these injustices. This conversation highlights how pollution and destruction of land, water, and air by the fashion industry negatively impact BIPOC communities here in America and brought awareness to how individuals can push for policy and industry changes.

Challenging Fashion’s Relationship with Land, Air, and Water: We kicked off Fashion Revolution Week with a deep discussion on fashion’s relationship with land, air, and water highlighting a cross sector of BIPOC thought leaders from around the globe. The conversation covered how our current western-centered worldview sees nature only as a resource, rather than an equal, and how fashion has been used as a means to erase cultures and traditions of people of color for centuries. Reparations are needed in the fashion industry to bring more womxn and BIPOC individuals to the table, bringing them into positions of leadership and slowing down the fashion industry as a whole to be in mutual relationship and respect with land, air, and water.

Tuesday, April 20: Ownership

Access & Ownership of Sustainable Fashion: Maya and Mica Caine, co-founders of Mive, discussed the roots of regenerative and sustainable practices in fashion and who has access to sustainable fashion. They highlighted how the “sustainable fashion” movement has been co-opted and rebranded, although the roots of regenerative and sustainable practices have been practiced by Indigenous peoples and communities of color for generations. Maya and Mica talked about pushing the fashion industry to consider ways to go beyond tokenism when practicing representation, bringing in more BIPOC individuals in leadership positions, highlighting designers, and making fashion more accessible for everyone. A notable quote from their IG Live conversation: ‘“Marketing is not an education.”

Who Owns Textile Waste?: Tara St. James, designer and consultant; Camille Tagle, co-founder and creative director of Fabscrap; Liz Ricketts, co-founder of The OR Foundation; and Chloe Assam, designer, researcher, community organizer and manager of Ghana Operations for The OR Foundation joined the Re:Sourced Fashion club on Clubhouse to talk about ownership of textile waste. Notably, Liz asked a poignant question related to retailer take-back programs and their realistic value: “Who has the right to profit from this waste?” Moderators also discussed the need for local and global policy change to tackle the issue of textile waste and also the regulation of the secondhand clothing trade, with Camille citing the opportunities that Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) policies present.

Cultural Appropriation and the Fashion Industry: In an industry inspired by nature, culture, and the world around us, fashion walks a fine line between cultural appreciation and appropriation. This visually focused session brought together diverse perspectives, including an academic, historian, activist, designer, and researcher, to take on the nuances of Cultural Appropriation in Fashion. Eugenia Paulicelli focused on the importance of fashion studies programs in including more cultural awareness and understanding of these intricacies, while Darnell Jamal Lisby showcased the balances designers have made between adoptive and permissive appropriation. Regardless of the inspiration or origins of a design, Brenda Equihua, a designer who balances her own creative process and bringing in cultural honor to her work, spoke to the intentionality of the process. “Intention means you take the time. The [fashion] industry currently isn’t set up for that.” Manpreet Kaur Kalra, an educator and activist, emphasized the need for understanding who holds the power and benefits most from the work, including who profits, what stories are told about the specific culture, and how we can honor the artisan and culture as the true original designer.

Wednesday, April 21: Workers

Ethical Narratives in the Fashion Industry: Manpreet Kaur Kalra, educator and podcaster at Art of Citizenry, and Joy McBrien, founder of Fair Trade brand Fair Anita, explored what it means to decolonize storytelling, practicing informed consent in crafting a narrative, and the power dynamics that we don’t consider in telling someone else’s story – even with good intentions. They discussed the power imbalances between the global north and the global south, how continually telling stories of others’ trauma perpetuates a single narrative and furthers the othering of our relationships with other cultures. Ultimately, your story is the only one that you own, and when you are telling someone else’s story, consider the power and privilege of having control over the narrative you’re sharing, ask how someone else wants their story shared, and center the maker as an individual, outside of their pain and trauma.

Mass Translation Posters: In partnership with Gabrielle Vazquez, Fashion Revolution USA’s NYC City Lead, with support from Alessandra Brescia and other creatives, our Instagram channel debuted a new mass translation project of our #IMadeYourClothes campaign into four languages: Kapampangan, Quechua, Catalan and Taíno. To learn more about the fashion revolution efforts in the countries where these languages are predominantly spoken, visit the webpages of our global teams in the Philippines, Colombia, Peru and Spain.

State of Play: Garment Worker Protections in the United States: To raise awareness around policy SB62 and the exploitation of garment workers in Los Angeles, Fashion Revolution USA hosted an informative panel featuring Sen. María Elena Durazo, Dr. Elizabeth Segran, Ayesha Barenblat, Marissa Nuncio, Sarah Ditty, and Santos Say Velasquez, a Los Angeles-based garment worker. Panelists discussed the importance of a holistic approach to regulating accountability in the fashion industry, particularly garment workers’ rights, and a solution that involves legislation, enforcement, advocacy, and community. Please sign the petition here, share our blog post, and join a virtual letter-writing event to get involved and support progress. In addition, brands/manufacturers/suppliers can support #SB62 by endorsing here.

Thursday, April 22: Nature

Rights of Nature Q&A: Kelly Camille Holmes of Native Max Magazine and Norma Baker-Flying Horse, native fashion designer, led a conversation on the relationship of Indengious people to the land, air, and water, highlighting traditions and stories of their peoples. They dove into the history of how the colonization of Indigenous peoples has negatively impacted their communities and erased their traditions, forcing them to assimilate away from traditional language, dress, and many elements of their cultures. As we begin to recognize the invaluable relationships with nature and the land that Indigenous peoples have always practiced, how can we center their voices as leaders in the movement and create an intersectional conversation that understands that much of the wisdom and knowledge we seek to create necessary change in the fashion industry and beyond has been othered and erased by colonizers for centuries?

Fashion Revolution Week Classroom: Regenerating Local Communities, Economies and, Environments: Fashion Revolution USA collaborated with Harvard Alumni for Fashion, Luxury, and Retail (FL&R) to create a unique classroom experience for Fashion Revolution Week. In this classroom, FL&R President Timothy Parent invited a diverse group of people, including Amy Hall, Gisselle Jimenez and Mitchell Harrison working on regenerative systems from a variety of perspectives who illustrated how we can simultaneously protect and create positive outputs for local people, economies and environments. By recognizing the intersectional solutions that exist with a regenerative framework, panelists empowered the audience to create positive outcomes for previously marginalized and exploited communities with a new vision for the fashion industry. This collaborative classroom was guided and supported with the help of Kelly Peaks (FRUSA) and Gabby Vasquez (FRUSA, The New School).

#BehindtheSeams: Four new brands joined Fashion Revolution USA for a continuation of our #BehindtheSeams series, this year debuted as Instagram Reels. Victoria Island-based Ecologyst, Detroit-based ISAIC, and Seattle-based Sassafras and Prairie Underground gave our digital audiences a behind-the-scenes look at their factories, opening up their doors by offering a transparent look at their production and process, and sharing #WhoMadeMyClothes. Many thanks to our Regional Coordinator and City Lead volunteers Alessandra Brescia, Camilla Sampson, Karen Hartman, and Olivia Gregg for bringing these features to life!

Friday, April 23: Gender

#DopeMenSew: Sewist, mens DIY designer and creator, Scorpio, of @sinsofmany joined Fashion Revolution USA for an IG Live to discuss gender roles in sewing, the #DopeMenSew community, lack of accessibility of pattern materials for men and many other subjects. “We’re programmed to think of fashion being one way,” said Scorpio, talking about the underrepresentation of men in the sewing community and lack of size inclusivity in the fashion industry. Scorpio also shed light on the powerful connections making your own clothing can foster, as well as recommended the Sew It! Academy and folks like Norris Dantá Ford, Mimi G, Michael Gardner, Prep Curry, and many others to learn from and follow. Get involved with Dope Men Sew on Instagram by using #DopeMenSew.

Fashion is a Feminist Issue: Tabitha St. Bernard-Jacobs, consultant at Tabii Just Strategies and deputy executive director of programming at Women’s March; Tameka Peoples, founder and director of operations at Seed2Shirt; Rosalinda Cruz, founder and chief experience officer of The Asor Collective; and moderator Whitney Bauck, freelance journalist, dove into the interconnected topics of gender issues, racial equity and agricultural systems within and across fashion’s supply chains. Panelists discussed the similarities of this work to revolutionize, or rebuild, the way brands and citizens consider these many topics to the work being done in the climate justice space. Equity, land access, representation and systemic change are at the heart of what’s needed to advance women’s agency from farmer to manufacturer to end consumer, especially that of Black, Brown, Indigenous and other women of color who have been historically and systematically disenfranchised in the fashion industry.

Saturday, April 24: Action

From Collective Action to Connected Action: Unleashing Tech for Good: This Clubhouse conversation, hosted by the Humankind Action Lounge, explored various stakeholders’ experiences of navigating the abrupt stop in fashion due to the pandemic and the importance of leveraging technology and community to achieve targets of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Moderated by Elizabeth Cabral, speakers included Jennifer Ewah, Jessica Turco, Mackenzie Mock, and Julia Perry. Together, they identified the importance of each other’s work and how collective and connected support and action are vital to driving change within the fashion industry.

Fashion Revolution Classroom: Financing Fashion: Amisha Parekh’s interactive class provided a foundational understanding of Sustainable Investment (SI) the types of SI including Exclusionary Screening, ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) Integration, and Thematic/Impact Investing, as well as defining Materiality Assessment, and how “values” (like human rights and environmental protection) are now being “valued” within investment portfolios. She explained that ESG investing has grown from $13T in 2012 to ~ $38T in 2020 and how the landscape is changing. Investors are now thinking more about long-term investments and how risk (such as an oil spill) affects a company’s value. New policies are being set in the EU to combat greenwashing and making it mandatory for public companies to disclose how they are contributing to environmental objectives. The outlook: progress is being made, especially in the EU.

Thrift Tips: Four thrifting experts–@the.thrifted.gay, @cakeplussize, @dinasdays and @thriftinginthecity_–joined Fashion Revolution USA to share a look at thrifting dos and don’ts, tuning in from Chicago, Minneapolis, Akron and Detroit respectively. Watch part one and part two of this takeover.

Sunday, April 25: Education

Around the World with Fashion Revolution: Shannon Welch, Fashion Revolution USA’s director of strategic initiatives and creative partnerships, joined Fashion Revolution for a round-robin look at the week’s events around the world. Co-presenters included Hadeel Osman, country coordinator of FR Sudan; Aigerim Akenova, country coordinator of FR Kazakhstan; Kamonnart Ongwandee, country coordinator of FR Thailand; Raina Rafie, country coordinator of FR Egypt; Salome Areais, country coordinator of FR Portugal; and Christian Stefanoni, communications lead for FR Mexico.

Made Incubator: The United State of Fashion II: The opening of The United State of Fashion II was a profound event with keynote speakers from different sectors of the fashion and beauty industry. Highlighting folks including a celebrity stylist to a lobbyist on Capitol Hill, panelists shared more about the fashion and business community’s role in addressing sustainable practices, responsible manufacturing, education gaps, economic and racial inequalities in the fashion and beauty industry, and barriers to opportunity for all. Hearing Ted Gibson and Jason Backe speak about the pain points of the beauty industry gave the audience a clear understanding of the environmental impact of the beauty and hair industry as a whole. We look forward to providing more digital knowledge and inclusion with industry stakeholders that make bold changes in this industry.

Student Ambassadors Takeover: Kelly Peaks, one of Fashion Revolution USA’s Student Ambassador Coordinators, spoke to five current ambassadors about their experiences in our student ambassador program. The conversations touched on their specific interests on issues within the fashion industry such as policy, circularity, shopping second hand, environmental issues, and more. Peaks also asked each student ambassador and the live, digital audience trivia question related to various issues surrounding the fashion industry, such as garment workers’ rights, clothing waste, and GHG emissions from clothing production. Many thanks to students Hannah Griffee, Joanne Onasi, Eva Bergloff, Ella Charnizon and Tess Stroh for participating!

Volunteer Events

This year, our Regional Coordinators, City Leads and Student Ambassadors brought the Fashion Revolution to life in new and unique ways across the United States. From clothing swaps to local sustainable clothing guides and much more, we’re thankful for the incredible work and efforts of our volunteer network to localize the brighter fashion future in their communities.

A hearty thank you to David W. Schropfer, CEO at The Safe, and DIY CyberGuy for helping facilitate a seamless virtual event experience with our sponsored Zoom account. We couldn’t have done it without you!

Today, WWF released the 2020 edition of their Living Planet Report which monitors the state of the planet – including biodiversity, ecosystems, and demand on natural resources – and what it means for humans and wildlife.

It is more urgent than ever that we tackle the global biodiversity and nature crisis. This report sounds the alarm for global biodiversity, showing globally an average 68% decline in the size of animal populations since 1970.¹ Nature is in jeopardy and we need to take urgent action!

What is biodiversity?

Simply put, biodiversity is the variety of life on Earth. Each individual of each species contributes to their local ecosystem, which in turn contributes to a wider ecosystem. Biodiversity is not just about the variety of species in an ecosystem, but also the genetic diversity which exists within each species. As species populations decline, this erodes genetic diversity, reducing the ability for a species to adapt to changes to its environment.

Why should we care?

Each ecosystem provides benefits to our planet, such as water purification, nutrient recycling, maintaining healthy soils, reducing pollution, absorbing carbon, regulation of floods and diseases, and much more. Biodiversity underpins the ecosystem, so when biodiversity is lost, we lose the ecosystems that humans rely upon to maintain our lives, such as the food we eat, the water we drink and the resources we use in our daily lives. Biodiversity is fundamental to human life on Earth and its loss will impact the health and wellbeing of people around the world, as well as deepening existing inequalities.

Humans are now overusing the Earth’s biocapacity, the ability of our planet’s ecosystems to regenerate, by at least 56%¹. This is like living off 1.56 Earths. We desperately need to rethink our global resource-intensive systems and find nature-based solutions that preserve our ecosystems, improve biodiversity and species populations and improve global health and wellbeing.

So, what are the key findings of the Living Planet Report?¹

- 68% decrease in population sizes of mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles and fish between 1970 and 2016.²

- 1 million species (500,000 animals and plants and 500,000 insects) are threatened with extinction.

- Humans are now overusing the Earth’s biocapacity by at least 56%.

- The worst decline is occurring in the tropical subregions of the Americas where we are seeing an average of 94% decline in population sizes.²

What is causing this catastrophic loss?

Whilst this varies in different regions of the world, The Living Planet Report states the biggest threats to biodiversity are:

- Changes in land and sea use (unsustainable agriculture, logging, transportation, urbanisation, energy production and mining) (43%-58%)³

- Species overexploitation (unsustainable hunting and poaching, fishing or harvesting) (18%-36%)³

- Invasive species and disease (11%-14%)³

- Pollution (oil spills, agricultural run-off, air pollution or water pollution) (2%-11%)³

- Climate Change (4%-13%)³

What’s the fashion industry’s role in this?

The fashion industry relies heavily on biodiversity, predominantly through the production and processing of all the different materials used to make our clothes, as well as the materials used for packaging. The fashion industry has a significant damaging impact on biodiversity, throughout the production process as well as during wear, care and disposal.

Changing land use

A large proportion of fashion’s biodiversity impact occurs due to habitat change resulting from agriculture for producing cotton, viscose, wool, rubber, leather hides or any other natural fibre. For example, fashion is a significant contributor to global deforestation with around 150 million trees logged every year to be turned into cellulosic fabrics, such as viscose. ⁵ In the Amazon, cattle ranching is the largest driver of deforestation. Between 2006 and 2010, beef accounted for around two-thirds of the export value of Brazilian cattle products, whilst leather was responsible for over one-quarter of the export value.⁶

The impacts of raw materials on nature will only increase as global demand for clothing increases. The fashion industry is projected to use 35% more land for fibre production by 2030 – an extra 115 million hectares that could be left to preserve biodiversity.⁴

Pollution

Whilst the full extent of fashion’s pollution impact is unknown, estimates have previously suggested that 20% of global freshwater pollution comes from the wet processing of the textile industry.⁷ Wet processing includes the scouring, bleaching, dyeing, printing and finishing of raw textiles which are water and chemical intensive processes.

Although many companies are cleaning up their acts and investing in cleaner dyeing innovations and better wastewater treatment, many of the world’s waterways are still being polluted. The Citarum River in Indonesia is home to around 2,000 textile factories where effluent from the dyeing and processing of fabrics has previously been dumped, with little or no regulation. This has caused extensive environmental and human health issues in the area.

Additionally, pesticides used for the production of our raw materials have been shown to reduce the populations of important species, whilst also eroding soil biodiversity. Although the cultivated area of cotton covers only 3% of the planet’s agricultural land, it uses 16% of all insecticides and 7% of all pesticides.⁸ Some have been banned and replaced, but many insecticides continue to kill or harm a broad spectrum of insects, including those that pollinate crops. ⁸

Climate Change

From raw material to disposal, the entire lifecycle of our clothing impacts our climate. It has been estimated that the fashion industry emitted around 2.1 billion tonnes of GHG emissions in 2018, equating to 4% of the global total. ⁹ Overall 52% of fashion’s GHG emissions come from raw material production and fabric and yarn preparation.⁹ This is driven by fashion’s obsession for synthetic oil-based materials such as polyester, which account for around 60% of the clothes we produce.¹⁰

We know that even just a small increase in global temperatures will have a devastating affect on nature. Fashion needs to wake up and take steps to decarbonise and move towards carbon neutrality.

What can the fashion industry do?

Globally, patterns of overproduction and consumption are indirect drivers of biodiversity loss as they underlie land-use change and habitat loss, the overexploitation of natural resources, pollution and climate change which are the drivers of biodiversity loss. We need to rethink current clothing consumption models and buy less, buy better, wear our clothes longer and figure out how to successfully recycle them in a circular manner.

In term’s of fashion’s impact on land, we need to be looking at regenerative agriculture which aims to rehabilitate and enhance the natural ecosystems. Currently , farmers producing fibres used by Patagonia, Eileen Fisher, Burberry and Kering Group (who owns Gucci, Saint Laurent and other major brands) are beginning to use regenerative farming methods in order to improve biodiversity and capture carbon, helping to lower CO2 levels. This method is now being used to produce raw materials used for fashion such as hemp, flax, bamboo and cotton and to raise cattle, goats and sheep.

Facing a climate emergency, fashion brands must also focus their recovery on breaking away from fossil fuels in their supply chain. A recent report by Stand.Earth outlines the steps fashion brands must take to reduce their emissions rapidly, including setting ambitious climate commitments with full transparency, focussing on renewable energy in supply chains, sourcing lower carbon and longer lasting materials, and reducing the climate impacts of shipping.¹¹

Whilst we all have a role to play to help nature recover locally and globally, businesses and policymakers need to take drastic action to ensure that nature is protected and restored. We still have a chance to put things right but we need change fast – we need it now.

Finally, the best way to motivate industry and governments to take action is by using your voice to demand action. This year we launched #WhatsInMyClothes? with the aim to encourage brands to tell us more about the materials, chemicals and environmental impacts of the clothes we wear. We deserve to know if our clothing is contributing to biodiversity loss or environmental degradation, so use your voice and ask your favourite brands #WhatsInMyClothes?

References

- WWF, Living Planet Report, 2020, https://livingplanet.panda.org/en-gb/

- This is the average decline in population sizes between 1970 and 2016, to calculate this, the Living Planet Index tracks the abundance of almost 21,000 populations of mammals, birds, fish, reptiles and amphibians around the world.

- The proportion of threats which vary regionally. For more information please see pages 18 – 21 in the Living Planet Report.

- Boger S. et al., Pulse of the Fashion Industry. Global Fashion Agenda, 2017, http://globalfashionagenda.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Pulse-of-the-Fashion-Industry_2017.pdf

- Canopy, CANOPY STYLE 5-YEAR ANNIVERSARY REPORT, 2018, https://canopyplanet.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/CanopyStyle-5th-Anniversary-Report.pdf

- Walker et al., From Amazon Pasture to the High Street: Deforestation and the Brazilian Cattle Product Supply Chain, Tropical Conservation Science, 2013 http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/194008291300600309

- Maxwell, McAndrew and Ryan, The state of the apparel sector: water, 2015, https://www.textilepact.net/pdf/publications/reports-and-award/glasa_2015_stateofapparelsector_specialreport_water.pdf

- Pesticide Action Network UK, Is cotton conquering its chemical addiction?, 2017, http://www.pan-uk.org/cottons-chemical-addiction/

- McKinsey and the Global Fashion Agenda, Fashion on Climate, 2020, https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Industries/Retail/Our%20Insights/Fashion%20on%20climate/Fashion-on-climate-Full-report.pdf

- Kirchain et al., Sustainable Apparel Materials, 2015 https://matteroftrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/SustainableApparelMaterials.pdf

- Stand.Earth, FASHION FORWARD: A Roadmap to Fossil Free Fashion, 2020, https://www.stand.earth/sites/stand/files/standearth-fashionforward-roadmaptofossilfreefashion.pdf

Written by Sienna Somers, Global Policy and Research Coordinator.

Before sitting comfortably on your sofa to read this article, you probably served yourself a glass of water or a cup of hot tea. Your day may have started early this morning, when, half asleep you gravitated towards the bathroom. Perhaps, you are part of the lucky ones planning to enjoy a warm bath on this cosy Sunday. Too often, we tend to forget what a privilege it is not having to think whether the water we drink is clean. More serious still, if the water will run when we turn on the tap.

Regrettably, nowadays more than 700 million people worldwide suffer from water scarcity1. While this number seems a small portion in comparison with the 7.8 billion people on earth, it is yet too many. And personally speaking, I find it frightful to hear that the UN anticipates a threatening water emergency in 2030. It’s just ten years away. I cannot help myself but think of this potential very near future where I, we, could be lacking water. We need to remember how important water is in our lives, in particular today.

Exactly two weeks ago, we were celebrating International Women’s Day. It is certainly not a coincidence that the day we honour women falls so close to the day we celebrate water. Because water is a women’s issue. My responsibilities within Drip by Drip – an NGO directed by women, whose mission is to tackle the water issues in the textile industry – have led me to better understand the impact of the current water crisis on women’s health, a topic that should have been brought to our attention a decade ago.

Women and Fashion – A long-term relationship

If you ask a woman whether she needs new clothes, her answer will likely be “Yes!”. It is therefore not surprising to read that 40% of German women buy new clothes they don’t need, nor that 50% to 80% of our wardrobe hasn’t been worn in the past 12 months. With the emancipation of women worldwide (nothing political here), their role in the economy has become more and more influent. Indeed, women drive 80% of all purchasing decisions!

While the growth of the fast fashion industry can partially be attributed to women consumers, it is sad to realise that the fashion industry itself has been built on the backs of women. Today, women compose the great majority of garment workers around the world. Most of them have no choice but to work in dreadful conditions, forced to accept low wages and excessive overtime. It is not sufficient to bear in mind the unsafe work conditions in many factories – which have notably caused the Rana Plaza factory collapse a few years ago. We must address the risk of sexual violence as much as the lack of regulation to guarantee a safe environment in the production countries.

Women and Water – What’s the connection?

In areas where running water is not provided in every house, the responsibility to fetch water from a traditional well or remote water pump lies with girls and women. Women who have to carry water over long distances while sometimes carrying their children too. Although limited researches have been conducted on the impact of water-fetching practices on women’s health, the World Health Organization (WHO)2 has already recognised serious implications such as spinal injury, neck pain, or spontaneous miscarriage from heavy workloads.

As running water is predominantly unavailable in the hottest and driest regions of the world – paradoxically the regions that would need it the most – women and girls have to leave home early to avoid unbearable heat. It’s also because water is existentially important for their family that they go off to fetch it in the early morning hours. Meanwhile, school is starting, and they’re missing it. The time women and girls spend walking to the water source, carrying it back home and boiling it so it would be drinkable; is as much time that is not available for other purposes such as learning.

Besides reducing school time, the lack of clean water becomes another important issue with the beginning of the period. Hundreds of millions of girls and women3 in the world lack of safe, clean, and private toilet in which to go to. With the absence of privacy during menstruation, women and girls have no choice but to stop school at a young age.

As if the privation of education isn’t enough, the lack of sanitary facilities exposes women and girls to an increased risk of attack. Women without water supplies and toilets within their homes become more vulnerable to sexual violence when travelling to and from public facilities, but also when they have to wait the nightfall to be able to ease themselves in the open.

Fashion, Women and Water – The urgency to take action

It is globally recognised that the fashion industry is jointly responsible for the pollution of our natural water resources. On the other hand, the women who are employed by the textile factories are more likely to live close to their workplace. They are consequently more predisposed to drink contaminated water from the groundwater, which exposes them to a higher risk of contracting water-related diseases. Concurrently, it does put their unborn child at risk too: during pregnancy, contaminated water significantly increases the risk of birth defects or illnesses for the child.

All of the above consequences on women’s health assume that they have sufficient water to drink, albeit polluted. In essence, women’s basic needs (i.e. hydration, sanitation, hygiene) are substantially different than men’s basic needs4. Did you know that women’s needs for water particularly rise during menstruation, pregnancy, the postnatal period and while caring for a sick family member? Probably not, like me. However, whenever their basic needs are not met, women simply cannot participate in any school, work or social activities. We shall not underestimate the directs effects of water scarcity on women’s life.