Overproduction, overconsumption and waste continues to be a growing challenge. It’s one caused by the global fashion industry’s linear ‘take, make, dispose’ model where mostly non-recyclable materials are extracted, made into products, and ultimately down-cycled, sent to landfill, exported through the global secondhand clothing trade or incinerated when no longer used. A crucial way to tackle textile and clothing waste is by investing in efforts to slow down consumption and increase clothing longevity, which would have a significant positive impact on the environment.

A growing number of major brands explain how they’re developing circular solutions that enable textile-to-textile recycling – 38% of brands in 2023, up from 28% in 2022, indicating a big jump from the previous year. Yet, less brands (29%) disclose their annual fibre mix and only 4% of brands publish the percentage of their products designed to enable circularity – which allows for the raw materials in disused clothes to be transformed into raw materials for new clothes.

Given that historically, major brands have released so-called ‘sustainable’ lines representing just a fraction of overall production, the absence of disclosed data on the quantity of a brand’s products that are truly circular does not inspire confidence. In order for these circular solutions to meaningfully contribute to addressing fashion waste, they need to become the norm rather than the exception in the industry. As a first step, greater transparency on brands’ fibre mix is crucial to understanding how to unravel the challenge of circularity.

To better understand the challenges facing the fashion industry, we invited a range of industry stakeholders and activists to provide in-depth analysis of the issues surrounding circular solutions and how governments and brands can adapt their strategies to create meaningful change. Here, you can explore some viewpoints featured in the Fashion Transparency Index 2023.

BUSINESS AS USUAL IS NOT VIABLE

JOSEPHINE PHILIPS, Founder and CEO, SOJO

It’s great to see more of the major fashion brands offering repair services, 26% this year compared with 20% in 2022 – as it not only shows a growing desire from consumers to partake in these practices, but also that brands are taking more accountability for their items post the point of purchase, promoting more circular behaviours.

While this moves the industry in the right direction, it’s important to note that shifting towards circularity needs to happen at every stage of the lifecycle of a product – not just at the point of disposal. For example, when garments are designed with longevity and end-of-life in mind, it entails a different approach towards material sourcing, ways of manufacturing, and end-of-life recycling. Another critical aspect is changing the narrative of how and what we buy. Ultimately, by continuing to pump out the same product volumes, we are not addressing the root-causes of textile waste – overproduction and overconsumption.

Using technology to streamline the tailoring and repair process allows SOJO to provide these services in an easy and accessible way, with online orders and door-to-door delivery of newly fitted or fixed items. The hope is that in the long term this will trickle down to changing consumer behaviour – decreasing consumption volume by helping people love their items for longer.

The British Fashion Council reports an estimated annual cost to brands of £7 billion caused by returns processes with approximately 30% of items bought online returned. With sizing or fit attributed as a leading factor in a customer’s decision to return (93%) and responding to the limited, generic sizing offered by most brands, our services help customers tailor their clothing uniquely to their bodies. In this way, care and customisation of garments happens not only at end-of-life, but also holistically throughout the lifecycle of the garments, supporting the reduction of waste through minimising returns and reverse logistic implications.

These two areas of focus for SOJO show that growing a business is not incompatible with championing a circular fashion industry. In other words, being better for the planet and people does not mean bad business. It’s a very exciting time to be part of the industry, however, scale is critical for creating systemic change. This calls for brands and investors to place bets and take risks to help champion these solutions. Ultimately it’s in their incentive to be part of this change, since it’s clear that the current business-as-usual mentality is not viable – for people, planet, nor profit.

YOUR WASTE, OUR PROBLEM: GLOBAL LANDFILLS WITH LOCAL CONSEQUENCES

MARÍA BEATRIZ O’BRIEN, COUNTRY COORDINATOR, FASHION REVOLUTION CHILE

This viewpoint was featured in the 2022 edition of the Fashion Transparency Index, and so the data has been updated to reflect this year’s findings.

The Atacama Region offers a landscape of unique beauty in earthy and soft colours. The Altiplano Plateau near the Andes Mountains is home to an ancestral and rich textile culture of camelid wool and local iconography.

A world away, the global textile industry based on a fast fashion system continues to accelerate overproduction and overconsumption. Clothing is also massively under-utilised and socially devalued in a race for cheap garments and ever changing trends.

The 1980s marked a new economic model for Chile. Once a strong and proud manufacturing country, the eruption of free market policies made it impossible for the national textile industry to compete with low-cost imports. It encouraged the sale and import of second-hand clothing. Free trade agreements in the 1990s deepened and cemented the model.

The Atacama Desert is the second largest textile landfill in the world. Iquique is the capital of the region and a tax-free port, a point of entry for Chile and neighbouring countries, especially Bolivia. Most bales come in unsorted and the regional government has banned throwing textiles in the local trash. Every year, thousands of tonnes of imported clothes must end up somewhere.

Out of sight is out of mind. Rich countries can export their waste to low-income countries; wealthy neighbourhoods can do the same inside their own territories. Alto Hospicio is a poor community of land seizures and self-built houses. Around 50 landfills are dispersed throughout the area, with little chance of clothing recovery. Picture a scenery of silence; a place where time seems to stand still. Open land where people and nature fade away–a perfect spot to dump and forget.

According to the Fashion Transparency Index 2023, only 12% (30/250 brands) of brands surveyed disclose the quantity of products produced during the annual reporting period, a disappointing drop from last year; In 2022, the data corresponds to 15% (38/250 brands). Without knowing how much is produced, it’s hard to control and hold brands accountable for the items dumped in landfills worldwide.

In Alto Hospicio, clothes leak chemicals into the ground and synthetic microfibres scatter through the air and into the ocean. Water and air are highly polluted, especially because incineration is a common practice. The Index shows very small efforts being made in publishing annual progress on the reduction of synthetic materials deriving from fossil fuels. In 2023, 27% (67.5/250 brands) disclosed this information, up from 24% (59/250 brands) last year.

The Atacama Desert landfill shows the scale of the global waste problem of the fashion industry. For the region, this is an environmental and social disaster. Current national import legislation is lax and has made it impossible for the local industry to resuscitate, suffocated by thousands of tonnes of unwanted clothing from the rest of the world. The region has the right to determine its own textile sovereignty and develop a local economy based on ancestral knowledge and creative design practices, such as the local strong up-cycling movement and sustainable independent designers trying to shape a new national industry.

*Some information included in this viewpoint was provided by Desierto Vestido, a civil society organisation in Iquique raising awareness on the impact on the Atacama Landfill.

WE CANNOT RECYCLE OUR WAY OUT OF OVERPRODUCTION

EMILY MACINTOSH, Senior Policy Officer for Textiles, European Environmental Bureau

The European Parliament recently adopted the EU ‘Textile Strategy’ – a policy plan to bring down the environmental and social impact of Europe’s textile consumption, with a focus on fashion and clothing. And while the approach contains good intentions, it remains to be seen whether its flagship actions on waste prevention will stop the most polluting business practices.

More and more used garments are set to be collected by local authorities when new EU rules requiring separate collection of textiles come into force in 2025. To finance this collection, the EU is working on plans for brands to pay fees that cover the costs of managing their products once they become waste, through so-called Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) schemes.

But what happens to collected textiles? While we might imagine donated clothing is all reused in Europe, in fact 1.4 million tonnes of used textiles with no EU market value were exported to third countries like Ghana and Kenya in 2020 alone, causing devastating environmental, economic, and human rights’ impacts.

And collecting more garments from 2025 in Europe will mean more and more items entering the global used clothing trade. That’s why money raised through EPR fees must go beyond paying for collection and sorting activities in Europe and support fair remuneration for communities in the Global South who receive exports of clothing castoffs from the EU.

The fees must also be set so they make a meaningful impact on reducing the volume of clothing produced every year because it is overproduction that is the root cause of the climate, environmental and social impacts of clothing consumption. We cannot allow brands to pay to pollute for a minimal fee. In other words, policymakers can ‘eco-modulate’ the fees by rewarding business practices rooted in sufficiency, quality, fairness, and transparency with a lower fee, and penalise those built around throwaway fashion, exploitation, and opaque supply chains with a higher one.

And with only 12% of brands currently revealing how much they produce, there is an opportunity to incorporate this obligation into EPR rules to make disclosure of data around how many products companies put on the market annually – and where they are produced – mandatory.

Because we cannot recycle our way out of overproduction. Overblown green claims on recycling hide the reality that the infrastructure and technology to turn ever-increasing volumes of clothing back into clothing is virtually non-existent, and the recycled fibres that do appear in ‘eco’ ranges make minimal environmental gains.

It’s only by remunerating workers properly at all ends of the supply chain as part of strategies to reduce volumes that we can ease the strain fashion is putting on our planet.

You can read more about overconsumption, waste and circularity in the 2023 edition of the Fashion Transparency Index.

Header image: Tim Mitchell & Lucy Norris from our Loved Clothes Last zine

Traditionally, fashion brand compliance efforts consisted of offloading the direct responsibility for human and environmental rights onto their suppliers, who absorbed this burden as a cost of securing the brand’s business. While the argument that brands aren’t responsible for the welfare of the workers in their supply chain has become indefensible, today many major fashion brands engage in purchasing practices with suppliers which are volatile and abusive. These practices, also referred to as unfair trading practices, include: cancelling and delaying orders; refusing to pay for orders; demanding retrospective discounts; issuing sudden changes in order volumes; and paying for orders very late. Sometimes, customers are wearing clothes before big brands have even paid the factories that made them.

To delve deeper into this topic, we invited a range of industry experts and stakeholders to provide on-the-ground insights and perspectives on how both brands and governments can remedy these issues. Here, you can explore some viewpoints featured in the Fashion Transparency Index 2023.

DEBT AND THE GARMENT INDUSTRY: DEBT AS A VEHICLE FOR GARMENT WORKER EXPLOITATION IN THE GLOBAL SOUTH

FAROOQ TARIQ, Pakistan Kissan Rabita Committee

TESS WOOLFENDEN, Debt Justice, UK

Throughout the Global South, many countries and workers depend on the garment industry for their income. Yet, conditions are often deeply exploitative and dangerous for workers, while profits are typically enjoyed by big multinational companies. Many of these inequalities link directly to debt.

For centuries debt has been weaponised against Global South countries and communities to the benefit of Global North elites.Not only do Global North governments, institutions and corporations use debt to extract vast wealth through interest payments ($2.5 trillion since 1970) shrinking the resources that countries have to meet citizens’ needs, they also use debt to tell countries what to do, forcing them to implement harsh austerity-based reforms as conditions of their loans. Global North governments and dominated institutions (like the World Bank and IMF) argue that these reforms – including cutting public spending, deregulating labour markets and liberalising economies – will achieve economic growth and allow countries to repay their debt and fund their development. But after decades, these outcomes have not materialised. Instead, Global South economies have stagnated and poverty and inequality rates soared while foreign investors have enjoyed new access to Global South markets on favourable terms.

For garment workers throughout the Global South, these reforms have created the perfect conditions for wage theft, poor and unsafe working conditions and restricted opportunities to unionise while multinational corporations make mass profits. Making up a majority of the workforce, women have been especially impacted whilst also bearing the brunt of public spending cuts which have forced vital services like healthcare into the home. These impacts are well documented, yet only 14% of major fashion brands involve gender experts in their human rights due diligence processes.

While there has been debt cancellation in the past, debt burdens and thus the ability of Global North powers to enforce economic reforms, remain high as the root causes – irresponsible lending and the Global South’s colonially rooted dependence on borrowing – remain unaddressed.

There are currently 54 countries in debt crisis. Many of these countries also rely on their garment industries, like Pakistan and Sri Lanka. In Pakistan for example, soaring inflation as a result of the debt crisis is causing the cost of essentials like food to skyrocket, which alongside poor and unpredictable wages in the textile sector means many workers can’t afford to eat full meals or pay for necessities. The high debt burden in Pakistan also means that governments do not have the resources to meet citizens’ needs, like funding healthcare or addressing the climate crisis.

In 2022, Pakistan was hit by devastating floods caused by the climate crisis. Recovery and reconstruction is estimated to cost at least $40bn but the country is expected to pay over $18bn in debt repayments this year.1 The floods have hit the textile industry hard. Yet because of a lack of national resources due to the debt, the industry has not been able to fully recover, putting many jobs and livelihoods at risk.

But all across the world, impacted communities are resisting the impacts of unjust debt and forced austerity. In Pakistan, the Kissan Rabita Committee and APMDD Pakistan are demanding an end to the unjust debt plaguing the country, calling on the government to stop repaying its loans, for Global North lenders to cancel the debt, and for living wages for all workers. Global South countries urgently need debt cancellation, free from economic conditions, so they have the resources and policy space to uphold the rights and wellbeing of all workers and citizens.

Addressing a lack of transparency is also key. How can we adequately hold corporations, governments and institutions accountable if we don’t know the true scale of what is happening? In the fashion industry this means big brands publicly disclosing information on their operations. For debt, it means creditors and borrowing governments sharing accessible information on their loans so citizens can hold their governments and lenders accountable.

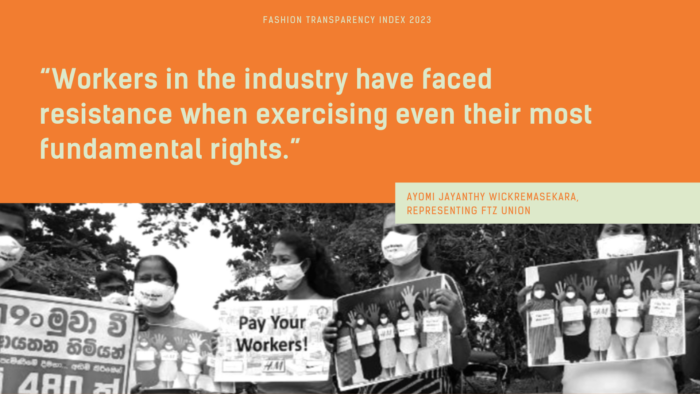

LOOKING AT UNIONISATION IN THE SRI LANKAN GARMENT SECTOR

AYOMI JAYANTHY WICKREMASEKARA, FTZ Union

Free Trade Zones & General Services Employees Union (FTZ&GSEU) was founded in 1982, which aims to protect the labour rights of workers within the Free Trade Zones and throughout Sri Lanka, especially women within the garment industry.

FTZ&GSEU leverages its vast network of garment workers, among both formal and informal union members, as well as their expertise in Sri Lankan labour rights and incorporates their lessons learnt when operating with garment factories’ management and owners.

The apparel industry in Sri Lanka plays a key role in developing the economy. For decades the industry has provided rural communities, particularly women, with access to economic opportunities. Subsequently, over 85% of employees within the industry are women, the majority of whom come from lower economic backgrounds and whose labour is undervalued. Despite the economic strength of this industry, many female workers are subject to widespread violations of the labour law and are highly vulnerable to gender-based violence (GBV) from their employers, supervisors, boarding house owners and other men living and working around the garment factories. This includes, but is not limited to, sexual, physical, and verbal harassment, exchange of sexual bribes for promotions and restrictions on utilising washroom facilities during work hours. Located far from their hometowns and separated from their families, workers are often reluctant to voice their concerns in fear of retribution from their employers.

Increasingly, violations of labour laws have also been observed with factories appearing to target and dismiss unionised workers. Even before the pandemic, trade union membership was low with a unionisation rate of only 15% across all sectors, and just 5% in the apparel sector. Sadly, even at a critical time, workers in the industry have faced resistance when exercising even their most fundamental rights.

FTZ&GSEU, alongside other trade unions, suggested to the EU GSP Monitoring mission the below findings:

The ILO has found the Sri Lanka Board of Investment (BOI) at high risk of violating international legal standards on freedom of association. The workers’ situation is the most arduous in the EPZs where freedom of association remains an illusion and employer-labour relations are usually managed by employee councils. These often undermine freedom of association and collective bargaining. Workers in Sri Lanka do not have access to remedy in case of anti-union retaliation as only the Department of Labour can bring cases concerning anti-union discrimination before the courts.

- Adapt the BOI Labour Standards and Employment Relations Manual to bring into an agreement with the international legal standards on freedom of association.

- The 40% union membership threshold should not be compulsory for recognition as a bargaining agent. This provision has no justifiable basis as stated by the ILO Committee of Experts on the Application of Conventions and Recommendations (CEACR).

- Change the Labour Law to bring into an agreement with ILO Convention 98, in particular regarding the limitation that only the Department of Labour can bring cases concerning anti-union discrimination to the courts.

- The CEARC also found entry into EPZs for trade union representatives are restricted. This is not justifiable and the right to access should be granted.

- Adapt policies on EPZs in particular discontinue the promotion of Employee Councils, and allow trade unions to take their place.

In Sri Lanka there are approximately 400 Garment factories. While some are being close down, there is only one Collective Bargaining Agreement at present (NEXT Manufacturing and FTZ & GSEU) and One Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) signed by FTZ and two other Unions (NUSS and SLNSS) with Joint Apparel Association Forum (JAAF).

“Brands need to go beyond policy commitments when it comes to freedom of association and lay out exactly how they plan to actively engage with trade unions and worker representatives along their supply chain to ensure genuine worker engagement. Importantly, this should include how they will work with suppliers to ensure a conducive environment for freedom of association and the development of representative trade unions at factory level. This is all the more important with the roll-back of trade union rights in multiple garment supplying countries and the continued rise of alternative ‘worker voice’ mechanisms; from the more traditional worker committee structures that often undermine trade union rights to collective bargaining, to the increasing use by brands of ‘worker voice’ tools that can simply never do the job of genuine dialogue and negotiation. As the sector continues to be impacted by economic turbulence, it is more important than ever that workers are able to collectively bargain for safer workplaces and decent livelihoods to ensure that it is not the lowest paid in the supply chain paying the cost for ongoing instability. And as more apparel brands become subject to due diligence legislation, now is the time for buyers to undertake stakeholder mapping along their supply chains to ensure that they are supporting workers, and importantly rights-holder groups such as women and migrant workers, to join and form trade unions to engage in participatory due diligence processes.”

Natalie Swan

Labour Rights Programme Manager, Business and Human Rights Resource Centre

FASHION HAS A PURCHASING PRACTICE PROBLEM: INDUSTRY WATCHDOG NEEDED

HILARY MARSH, Transform Trade

Fashion has a purchasing practice problem. Whilst the data from this year’s report demonstrates an upward shift by brands in their transparency of human rights due diligence processes (68% in 2023 compared to 34% in 2020), there has been no movement on publicly committing to paying suppliers within even 60-day time frames. Late payments are a part of a bundle of purchasing practices which directly impact on a supplier’s operations, potentially creating the very issues due diligence tries to mitigate. Voluntary initiatives to improve purchasing practices have proven ineffective; regulation is desperately needed to embed stability and consistency in fashion supply chains and level the playing field.

It is concerning that the simple act of disclosing policies to pay suppliers within a maximum of 60 days is proving a struggle for major fashion brands, with only 11% publishing a policy to pay suppliers within 60 days, stagnant since last year. Much of the disclosure made by brands and retailers, for instance in HRDD reporting, is based on information provided by suppliers, about the workers employed by suppliers or environmental impacts incurred within supply chains. The lack of information provided about the actions of the retailers themselves is a vital missing piece of information. Particularly given the role that brands’ purchasing practices can play in enabling or undermining improved labour rights. For example, the ILO’s 2017 report pointed to a correlation between companies committing to pay at least the cost of production and a 20% uplift in wages. When brands pay their suppliers months late, then it is suppliers, and ultimately garment workers (experiencing poor labour rights including incorrect overtime payments, delayed and inaccurate wages), who are effectively subsidising fashion brands’ operations, and as it stands only 4% of fashion brands share the number of orders that have retrospective changes to their previously agreed payment terms.

But it isn’t just late payments which impacts suppliers’ operations. In a survey from the University of Aberdeen released this year of 1000 Bangladeshi manufacturers producing clothing for global brands and retailers, more than 50% reported at least one of the following four unfair practices by brands and retailers: cancellation of orders, price reduction, refusal to pay for goods dispatched or in production, and delaying payment of invoices of more than three months. These methods used when fashion brands buy clothing dump inappropriate, unexpected, and excessive risks and costs onto their supplier factories and undermine the market for brands treating manufacturers fairly. Practices like this were once widespread in the food retail sector but were banned with the establishment of a Supermarket Watchdog enforcing a Code of Practice. Its introduction has seen a huge reduction in these practices with 79% of suppliers surveyed reporting experiences of code breaches in 2014, falling to 29% by 2021.

We urgently need legislation for the fashion sector. Luckily, there is growing support to follow suit. The proposed ‘Fashion Watchdog’ (or Fashion Supply Chain Code Adjudicator, as set out in a UK Private Member’s bill) would oversee fashion brands’ buying practices and be able to reverse unfair decisions in line with a code of practice for the industry.

If you are in the UK and in support of fair purchasing practices by fashion retailers and brands selling in the UK market, head to our Fashion Watchdog MP Pledge page, and contact your MP today to ask them to support this vital proposal.

STATE-IMPOSED FORCED LABOUR IN TURKMENISTAN’S COTTON HARVEST: THE NEED FOR SUPPLY CHAIN TRANSPARENCY

RUSLAN MYATIEV, Turkmen.News

ROCIO DOMINGO RAMOS, Anti-Slavery International

Turkmenistan’s cotton industry is underpinned by a state-sponsored forced labour system.

Every year, the government forces hundreds of thousands of public sector workers, like teachers and doctors, to pick cotton, pay a bribe, hire a replacement worker, or face threats of lost wages and termination of employment. In many cases, children pick cotton alongside their parents. Farmers are forced to meet official production quotas under threat of penalties. Private businesses are also forced to contribute workers or services, for example, vehicles to transport forced labourers. The Turkmen government is resisting reforms to the industry and has taken harsh actions against those who report on abuses in the sector.

Given the government’s total control of cotton production, for any company sourcing cotton or cotton products directly from Turkmenistan, it is a fact that their product is tainted with forced labour. But there is also risk for those who source from countries that produce textiles using Turkmen cotton, yarn and fabric. For companies in the United States, due to a Customs and Border Protection Withhold Release Order on Turkmen cotton, they are illegally importing such products. To assess and mitigate that risk, full mapping of supply chains and transparency is integral.

Turkmenistan is the 10th-largest cotton producer in the world and has a vertically integrated cotton industry. Turkmen cotton from any stage of production can find its way into supply chains. According to UN Comtrade data, in 2022 Turkmenistan exported cotton and cotton products valued at almost US$300 million to several countries across the world. Research by Cotton Campaign members on commercial trade and value chain databases shows that Turkmen cotton enters the global markets through two main streams:

- As finished goods produced in Turkmenistan and exported through direct trade routes or transhipped to, for example, Kazakhstan, Russia, Belarus, Italy, the U.S., and Canada;

- Through suppliers in countries that produce textiles using Turkmen cotton, yarn and fabric, in particular Turkey, but also China, Pakistan, and Portugal, among others. For example, Turkmenistan is the largest source of fabric imports to Turkey, and the second largest source of yarn, after Uzbekistan.

The repressive system of state imposed forced labour in Turkmenistan makes it impossible for brands and retailers to conduct any credible due diligence on the ground to prevent or remedy forced labour. For this reason, companies must map out their entire textile supply chains, down to the raw material level, and eliminate all cotton, yarn and fabric originating in Turkmenistan, with a focus on identifying the intermediary routes by which it reaches supply chains. It is disappointing that transparency is low across fashion’s supply chains, especially at raw material level where just 12% of major fashion brands publish their raw material suppliers, like cotton farms.

Transparency helps a company’s own knowledge and due diligence and supports civil society working to bring all companies to the same level. Yet, as we see with this year’s Fashion Transparency Index, this level of transparency is minimal.

WE CAN’T LET ANOTHER GENERATION OF GARMENT MAKERS DEPEND ON POVERTY WAGES.

ANNE BIENIAS, Clean Clothes Campaign

The Fashion Transparency Index and the Transparency Pledge have been at the forefront of pushing for the enormous increase in the amount of brands publishing their suppliers list over the past few years, with more or less detail, which has been immensely important for the work of the Clean Clothes Campaign network and other labour rights groups.

It’s impossible to hold brands accountable for violations in their supply chain if there is no oversight of which brands are producing where. However, transparency at this level is not enough. A list of factories on a brands’ website or on the Open Supply Hub does not tell a consumer under what conditions their item of clothing was made or how much the maker was paid to make it.

This is tricky, as more and more brands make bold claims or promising commitments about paying living wages to workers in their supply chain, roughly 28% of the brands covered in this research. We can clearly see that this is the first step towards a living wage and with the lowest threshold. The more specific it gets (so moving from a commitment to an action plan and then to implementing that action plan) the fewer brands are able to provide any evidence or details.

Only three brands in this research can provide evidence of paying some of their workers a living wage, despite decades of corporate social responsibility and voluntary multi-stakeholder initiatives. This unfortunately means that most workers in these brands’ supply chains are still paid poverty wages; a minimum wage – where there is a statutory minimum wage – or per piece. Statutory minimum wages are far below living wages in garment production countries.

The minimum wage in Bangladesh has not been revised for five years, which essentially means that workers’ purchasing power has decreased over the past five years because of inflation and rising cost of living. The situation in other countries is similar: workers’ wages don’t rise as quickly as inflation. The gap between wages earned and what constitutes a living wage is growing, despite all good intentions by some fashion brands. It’s clear that workers can’t wait for brands to figure it out by themselves, but that immediate action in the form of legislation or other binding mechanisms to stop this crisis is required.

That is why Clean Clothes Campaign is a key partner in the Good Clothes Fair Pay campaign, calling on the European Union to adopt specific legislation that requires companies to conduct living wage due diligence in their supply chains. We can’t let another generation of garment makers depend on poverty wages.

You can read more about decent work and purchasing practices in the 2023 edition of the Fashion Transparency Index.

Header photo by Marcel Strauß on Unsplash

In July, we launched our eighth edition of the Fashion Transparency Index, a tool we use to incentivise the world’s largest fashion brands and retailers to disclose more information about their social and environmental policies, practices and impacts, in their operations and supply chain.

The climate crisis is growing in intensity and urgency, yet we are still not seeing sufficient action from the fashion industry to address its role in exacerbating this crisis. This is why, this year we introduced a new indicator to understand major brands’ reliance on coal. Few brands (6%) disclose the proportion of their supply chain that is powered by coal and which geographic regions are still reliant on fossil fuels, painting an unclear picture of the scale of the problem we are facing. How can brands uphold their decarbonisation commitments if they can’t, or won’t, disclose how much coal they are using to begin with?

Another new indicator we introduced this year looks at brands’ investment in decarbonisation, to help us understand what actions brands are taking to actively support their suppliers in their green transition. The green transition refers to the changes that will achieve sustainable production so that the fashion industry no longer endangers the planet, changes such as switching to renewable energy and reducing the reliance on fabrics derived from fossil fuels. Disappointingly, only 9% of major fashion brands disclose their investment in decarbonisation, which raises the question; if brands aren’t investing in their sustainability commitments, who is?

To understand this issue further, we invited a range of industry experts and stakeholders to discuss the green transition, to give insight on how brands can prepare for this shift and how they can support their suppliers throughout the process. Here, you can explore some viewpoints featured in the Fashion Transparency Index 2023.

DECARBONISATION REQUIRES HONESTY, ACCOUNTABILITY AND ACTION

RUTH MACGILP

Fashion Campaign Manager, Action Speaks Louder

According to the Apparel Impact Institute, the majority of greenhouse gas emissions that fashion brands are responsible for are produced in their supply chain, concentrated at the material production and processing stage. This means that, while it’s promising to see some brands in this years’ Index committing to renewable energy in their own operations through RE100, without action to build or procure local and additional wind and solar power at the manufacturing level, the fashion industry will fail to meet its climate targets. At Action Speaks Louder, we close this do-say gap by mobilising communities who are harmed by corporate greenwashing. More often than not, we find that brands’ sustainability teams are blind to the reality of what it will take to reach their own climate targets: a total overhaul of the energy system that powers their supply chains. To shift the dial, we need to see bold, public facing commitments to build and procure clean, renewable energy.

“Despite increasing media attention on multi stakeholder initiatives, summits, pacts and charters, fashion’s carbon footprint continues to grow. Meanwhile, not one brand in the Index is disclosing an absolute reduction in energy consumption. So do commitments even matter anymore? Of course, targets alone are not enough. We need transparency on the actions taken to reach targets and robust accountability mechanisms for false sustainability claims.”

Staggeringly few brands disclose the energy mix in their supply chain, details on renewable energy procurement or even what constitutes their scope 3 emissions, making it impossible to scrutinise the feasibility of their climate commitments and sustainability claims. This dangerous lack of transparency leaves room for loopholes and false solutions such as biomass combustion, carbon offsetting and renewable energy credits that allow emissions-as-usual to continue. Like many issues explored in the Index, the challenge of decarbonisation is underpinned by a deeply flawed power imbalance between buyers and suppliers. Climate targets are not just something to splash on an impact report while farms, factories and mills are left to pick up the pieces. Instead, implementation of a successful decarbonisation strategy requires providing the financing, technical assistance and policy tools that allow suppliers to invest in the most effective solutions. Asia Garment Hub calls this approach ‘supplier led, brand supported’.

“Climate targets are not just something to splash on an impact report while farms, factories and mills are left to pick up the pieces.”

Brands tell us that the road to 100% renewable energy isn’t 100% clear. But this isn’t true. The clean technologies are all commercially available if big fashion puts the spending power behind them and commits to transparency about their progress. Those brands which don’t, but continue to claim they have climate credentials, will lose the trust of their customers and broader civil society.

WE STAND HERE WILLING AND READY TO MAKE THE TRANSITION BUT WHAT ARE THE INVESTMENTS NEEDED FOR A SUSTAINABLE ECONOMIC AND ENVIRONMENTAL FUTURE?

ALIA LODHI

Director, Inter Market Knit (pvt), Ltd. Lahore, Pakistan

In our journey we have relied on our brand partners to lead the way forward and guide us. Traditionally, our responsibility has been to follow brands’ supplier codes of conduct and the United Nations United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights diligently, strongly believing that they serve the best interest of all stakeholders. These guidelines were developed by various organisations with a global perspective encompassing everything from production system development to sustainable wage disbursement, health and safety and social responsibility. We have been engaged in calculations on how each of these systems impact the bottom line of our business. It really did work for us, but this new definition of responsibility – making the green transition demands a paradigm shift – perhaps even a new definition of a business entity!

The SDGs have set the stage for challenging current world views and opening the door for new legislations which could have near term effects on green transition. We have seen that an increasing number of brands, especially in Europe, are willing to understand the on-the-ground realities of the Global South. Could the first success story be of how a small manufacturer in the Global South catalysed change? How can those with more resources create conditions that make the green transition viable and attractive? How can the world’s largest fashion brands and retailers enable manufacturers in the textile industry to play an active and a more effective role in green transition? We stand here willing and ready to make the transition but what are the investments needed for a sustainable economic and environmental future? This year’s Global Fashion Transparency Index asks brands, for the first time, if they disclose their level annual investment in decarbonisation, which includes financing the costs of green transition. Fashion Revolution’s research finds that 91% of brands reviewed do not disclose this information, which signals that financing the transition is not a priority for them, though it is an expectation on us to be more sustainable.

With an increased radius of responsibility reaching far beyond the realms of compliance, we want to foster stronger and long term partnerships, and promote absolute transparency. We crave for a deep understanding from our partners of the challenges that small manufacturers like us are challenged with regarding green transition in the face of market driven prices. In my business, we strive to create awareness that leaving a better world for the future generations requires a clear understanding of the impact of our actions with and without these transformative steps. While we believe that investment and taking responsibility for implementing changes successfully, is a shared burden between the brands and their suppliers, small manufacturers like ourselves can benefit by showcasing our efforts to help win future investments from brands. This kind of showcasing can be mutually beneficial and can redefine the future of the textile industry.

BEYOND REPORTING AND TARGETS, WE ALSO NEED AN ACCELERATION IN ACTION

PAULINE OP DE BEECK

Environmental Portfolio Lead, Apparel Impact Institute

As we approach the halfway mark to 2030, the increase in detailed scope 3 disclosure, setting of near & long-term targets, and published progress against them is welcome. However, brands reporting on these indicators still represent less than half of the sector well below what is needed for 1.5C alignment by 2030. We need foot-printing and targets set to be at 100% by 2025.

One of the most encouraging improvement indicators is the increase in environmental risk and impact reporting linked to financial statements: 22%, up from 13% in 2022. This demonstrates that more brands are seeing the relationship between their business’ viability and the need to align to net zero. This understanding catalyses deep decarbonisation efforts

While we celebrate these advancements, it is important to acknowledge areas that still require attention. A small fraction of brands (6%) disclose the proportion of their production powered by coal, and only 9% report supply chain renewable energy. To fully harness the potential of coal phase-out and renewable energy, brands must expand their efforts beyond pilot projects and embrace large-scale implementation. This entails mapping suppliers’ energy sources, setting specific targets, and formulating comprehensive plans to achieve them. Additionally, we must come together as an industry to address shared challenges.

A key step lies in establishing a common understanding of the most viable alternative sources for thermal energy and electricity, taking into account country- and facility specific contexts. Not all alternatives will be equally feasible from a financial or technological standpoint. By fostering collaboration and knowledge exchange, we can identify the optimal energy solutions that strike a balance between environmental impact and practicality. Another critical factor is the evolution of policy frameworks in garment producing countries. We have seen promising examples, such as in Bangladesh, where brands have actively engaged with policymakers to develop regulations that facilitate renewable energy deployment. By replicating these efforts in other countries, we can accelerate facility-level installations and explore alternative avenues such as corporate Power Purchasing Agreements.

The commitment of brands to their targets can be truly measured by the level of transparency regarding their green investments. While the current disclosure rate stands at less than 9%, we believe this indicator will increase dramatically by 2025. Targets must be accompanied by robust net-zero transition plans that outline the associated costs. With just 6.5 years left to halve emissions, we have to mobilise action and secure the required capital.

You can read more about climate change, biodiversity and the green transition in the 2023 edition of the Fashion Transparency Index.

Header image by Nuno Marques on Unsplash

Fashion Revolution Week is our annual campaign bringing together the world’s largest fashion activism movement for seven days of action. It centres around the anniversary of the Rana Plaza factory collapse, which killed around 1,138 people and injured many more on 24 April 2013.

This year, as we marked the tenth anniversary of the Rana Plaza factory collapse, we remembered the victims, survivors and families affected by this preventable tragedy and continue to demand that no one dies for our fashion. To define the next decade of change, we translated our 10-point Manifesto into action for a safe, just and transparent global fashion industry. Our campaign platformed the work of our diverse Global Network who provided local interpretations of their chosen Manifesto point(s). We believe that while fashion has a colossal negative impact, it also has the power and the potential to be a force for change. Together, we expanded the horizons of what fashion could – and should – be.

Here, catch up on some of the week’s highlights and find out how to stay involved with our work, all year round.

Remembering Rana Plaza

Fashion Revolution Week happens every year in the week coinciding with April 24th, the anniversary of the Rana Plaza disaster. On April 24th 2013, the Rana Plaza factory building in Bangladesh collapsed in a preventable tragedy. More than 1,100 people died and another 2,500 were injured, making it the fourth largest industrial disaster in history. On April 24th, we paused all other campaigning to pay our respects to the victims, survivors and families affected by this tragedy, and came together as a global community to remember Rana Plaza.

As we reflect a decade on, we are inspired by and celebrate the progress made in the Bangladesh Ready-made Garment (RMG) sector by the Accord. The International Accord on Fire and Building Safety was the first legally-binding brand agreement on worker health and safety in the fashion industry and is the most important agreement to keep garment workers safe to date. This year, we pay tribute to the joint efforts of all Accord stakeholders who have significantly contributed to safer workplaces for over 2 million garment factory workers in Bangladesh, including the Bangladeshi trade unions representing garment workers, alongside Global Union Federations and labour rights groups. We welcome the introduction of the Pakistan Accord and would like to see the adoption and success of the International Accord replicated in all garment producing countries.

Manifesto for a Fashion Revolution

Our theme for Fashion Revolution Week 2023 was Manifesto for a Fashion Revolution. Back in 2018, we created a 10-point Manifesto that solidifies our vision to a global fashion industry that conserves and restores the environment and values people over growth and profit. This year we called on citizens, brands and makers alike to sign their name in support of turning these demands into a reality, boosting our signature count to 15,500 Fashion Revolutionaries and counting. We are immensely grateful to everyone who has and continues to sign; our power is in our number and each signature strengthens our collective call to revolutionise the fashion industry.

To campaign for systemic change in the fashion industry, we themed the week around complementary Manifesto points, providing ways to be curious, find out and do something daily around each of them. From supply chain transparency to living wages, textile waste to cultural appropriation, freedom of association to biodiversity, we shared global perspectives and solutions to fashion’s most pressing social and environmental problems.

Over the past ten years, the noise around sustainable fashion has only got louder. But meanwhile, real progress is too slow in the context of the climate crisis and rising social injustice. That’s why Fashion Revolution Week 2023 was an action-packed and future-focused campaign that amplified the actions and perspectives of Fashion Revolutionaries around the world.

View this post on Instagram

Global Conversations

To capture these global perspectives, we launched the Fashion Revolution Map on Earth Day, which coincided with the start of Fashion Revolution Week. Developed by Talk Climate Change, the Map served as a global forum to reflect on the week’s themes and events, using our Manifesto as a talking point. Fashion Revolutionaries continued the discussion offline by inviting their family, friends, colleagues and classmates to imagine what a clean, safe, fair, transparent and accountable fashion industry would look like with us. These conversations were then recorded on the Map as a source of inspiration and knowledge exchange.

Anyone can be a Fashion Revolutionary; it starts with a simple dialogue about the changes you want to see in the fashion industry. Make your voice heard by contributing to our map today and help change the fashion industry through the power of conversation!

View this post on Instagram

Good Clothes, Fair Pay Highlights

Ten years on from Rana Plaza, poverty wages remain endemic to the global garment industry. Most of the people who make our clothes still earn poverty wages while fashion brands continue to turn huge profits. At Fashion Revolution, we believe there is no sustainable fashion without fair pay which is why we launched Good Clothes, Fair Pay as part of a wider coalition last July. The Good Clothes Fair Pay campaign demands living wage legislation at EU level for garment workers worldwide, building on Manifesto points 1 and 2.

During Fashion Revolution Week, our EU teams coordinated awareness events, campaigns and marches to mobilise signatures for this campaign. On April 25th, we headed to the European Parliament with Fashion Revolution Belgium to demand better legislation in the fashion industry. The day of action consisted of a panel discussion between Members of the European Parliament and impacted fashion stakeholders, and ended with a stunt outside the Parliament. Fashionably Late highlighted that the EU is running out of time to act on poverty wages in fashion. This stunt was replicated by our teams in Germany, France and the Netherlands throughout Fashion Revolution Week to demonstrate EU-wide solidarity with the people who make our clothes.

We have less than three months left to collect 1 million signatures from EU citizens to push for legislation that requires companies to conduct living wage due diligence in their supply chains, irrespective of where their clothes are made. If you are an EU citizen, sign your name here. If you’re unable to sign, please support the campaign by sharing it far and wide online.

View this post on Instagram

Fashion Revolution Open Studios Highlights

Fashion Revolution Open Studios is Fashion Revolution’s showcasing and mentoring initiative since 2017. Through exhibitions, presentations, talks, and workshops with emerging designers, established trailblazers and major players, we celebrate the people, products and processes behind our clothes.

This Fashion Revolution Week, Fashion Revolution Open Studios joined forces with Small but Perfect to spotlight the work of 28 European SMEs taking part in their circularity accelerator project. Forming part of this European events programme, Fashion Revolution Open Studios held a two-day event in partnership with The Sustainable Angle and xyz.exchange at The Lab E20. The event showcased seven innovative designers from the Small But Perfect cohort of sustainable SMEs and displayed how they are embedding circular solutions into their work, from crafting grape leather handbags to developing community approaches to making and working together. Alongside the exhibition, there were livestreamed webinars, workshops and panel discussions to explore the projects and hear about some of the the challenges facing small businesses and the industry at large in switching to circular business models.

Global Network Highlights

With 75+ teams from all around the world, Fashion Revolution Week 2023 championed the perspectives and contributions of our Global Network. Here are just a small selection of highlights from our country teams:

Fashion Revolution New Zealand unpacked each Manifesto point with industry trailblazers in an Instagram Live series.

Fashion Revolution teams in Bangladesh and Sweden co-organised a virtual panel discussion on shifting consumer behaviour.

Fashion Revolution Singapore celebrated the launch of their digital zine MANIFESTO.

Fashion Revolution teams in Iran and Germany collaborated on Women, Life, Freedom, a joint exhibition.

Fashion Revolution Nigeria shared the stories and journeys of local slow fashion brands.

Fashion Revolution Argentina invited us to join their Wikipedia edit-a-thon.

Fashion Revolution teams in Vietnam, South Africa and Scotland hosted local community clothing swaps.

Fashion Revolution India won the Elle Sustainability Award for Eco-Innovation in Fashion.

Fashion Revolution Uganda brought together the country’s top designers and brands at Kwetu Kwanza.

Fashion Revolution teams in UAE and Canada both held local design competitions for students.

Fashion Revolution Hungary championed the revival of traditional folklore practices in clothing and fashion.

Fashion Revolution USA discussed the fashion industry’s impact on people and planet in a 2-part Zoom series.

Fashion Revolution Uruguay hosted Fashion Celebrates Life, a community picnic themed around Manifesto point 10.

Fashion Revolution teams in Chile and Portugal shared their Fashion Revolution Week highlights with us on Instagram Live.

You are Fashion Revolution

We are so grateful to everyone in our community for getting involved in Fashion Revolution Week on social media and beyond. Every single voice makes a difference in our fight for a fashion industry that conserves and restores the environment and values people over growth and profit.

While Fashion Revolution Week 2023 may be over, our community, our campaigning and our movement continues, 365 days a year. Please join us in fighting for systemic change by:

Following us on social media: Stay up-to-date by following us on Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, LinkedIn and YouTube, and signing up to our weekly newsletter.

Finding your country team: Connect with the teams in your region by following them online, attending their events and volunteering with them. Find your country team here.

Using our online resources: Our website is a treasure trove of information, from how to guides and online courses to annual reporting on transparency on the fashion industry. Get started here.

From all of us in the Fashion Revolution team, we appreciate your support and we look forward to seeing you next year!

This article was written by Fashion Revolution Brasil. You can read the Portuguese version here.

Deforestation of more than 10,000 km² and humanitarian crisis in the Amazon

In 2022, more than 10,000 km² were deforested in the Amazon region: the equivalent of cutting down nearly 3,000 soccer fields per day of forest. This destruction threatens the region’s biodiversity, rainfall, health and food security for millions of people and further intensifies the effects of the global climate crisis.

Even in the midst of this worrying scenario, none of the 60 brands analysed in the Fashion Transparency Index Brazil 2022 disclose commitments to zero deforestation and only 8% of the brands disclose public lists of their raw material suppliers. Companies have the responsibility to look over their supply chains, identify potential risks and impacts to human rights and the environment, and address them. The lack of visibility on these topics opens up gaps for environmental and social damage to occur.

Based on the idea that development is intrinsically linked to economic growth, increased production capacity and profit, the natural, social and cultural wealth of the Amazon region remains under threat. Indigenous peoples, who act as protectors of forests and shields against deforestation, are having their rights dismantled and their population seriously impacted by the advance of livestock, agriculture and mining.

Next, we bring more information on what is happening in the Amazon and how this devastating scenario relates to fashion.

View this post on Instagram

#WhatsInMyJewelry and the Yanomami tragedy

Data from Map Biomas shows that, between 1985 and 2020, the mined area in Brazil grew six times. This expansion of mining coincides with its advance on indigenous territories and conservation units. From 2010 to 2020, the area occupied by mining inside indigenous lands grew by 495%.

The impacts of deforestation, the destruction of water streams and the illegal extraction of gold is evident in the Yanomami territory. The Yanomami are an indigenous group that lives in the north of the Amazon region and have become the target of a serious humanitarian crisis. In addition to various environmental impacts, the Yanomami face hunger, malnutrition, an increase in cases of malaria and other infectious diseases, mercury contamination and a growth in violence against indigenous people surrounded by illegal mining.

Traceability and transparency in the gold and precious metals supply chain is precarious. The ore extracted clandestinely from Brazilian indigenous lands can end up in jewelry or electronic filaments used around the world. After having its real origin covered up, the metal is mixed with legalized gold in refineries, enters the international market and can be acquired by large global companies without them being able to trace its real origin.

The opaque traceability only reinforces the importance of companies carrying out robust due diligence processes for human and environmental rights in their supply chains. Transparency is needed across the entire fashion value chain. Questioning the origin of what we wear goes beyond just our clothes and should also include our accessories. We should ask the brands #WhatsInMyJewelry

New infrastructure project could worsen local situation

Another example of how the relentless pursuit of profit and increased production efficiency can negatively impact the environment and local communities is a project that is expected to be voted on by the Brazilian Federal Supreme Court at the end of May: the Ferrogrão. The approval of the project could further accentuate the critical situation of devastation in the Amazon.

Ferrogrão is a project for the construction of a railroad of almost a thousand km to transport grain from Mato Grosso to Pará. One of the objectives of the infrastructure project is to increase economic efficiency in the distribution and storage of grains, given the expansion of the Brazilian agricultural frontier.

The project is sold as a green tunnel, but privileges the interests of the agribusiness market to the detriment of the preservation of the environment and the guarantee of ethnic and territorial rights. If it is constructed as planned, Ferrogrão will cross the Jamanxim National Park, a Conservation Unit of Full Protection. The railroad could also intensify land conflicts and potentiate socio-environmental impacts already suffered in the region. At least three ethnic groups would be impacted by the construction of the railroad (Munduruku, Kayapó, Panará) and there is a risk of deforestation of more than 230 thousand hectares.

These and other impacts with the potential to accelerate the expansion of the agricultural frontier and the intensification of the production of commodities based on monoculture and land concentration have already been denounced by indigenous peoples.

Transparency, consciousness and dialogue

Amidst this worrying scenario of devastation, in which biodiversity and local communities remain threatened, we need fashion brands to take a stand and be transparent about the origin and traceability of their products.

We need transparency about where what we consume comes from. We need to rethink the logic of profit. We need a development model that considers the nature and culture of people as a value and an element capable of generating socioeconomic well-being in the long term. We need to include affected peoples in the dialogue for improvements, consulting with them before projects can be approved. We need government oversight and public policies that favor Nature and people.

We invite you to ask the brands #WhatsInMyJewelry, #WhatsInMyJewelry and accessories, demanding transparency about the production processes. You can also make donations to help the Yanomami people and sign this petition against the construction of Ferrogrão.

Further reading

How transparent are the world’s 250 largest fashion brands?

The 2022 Global Fashion Transparency Index

The 2022 Brasil Fashion Transparency Index

24th April 2023 marks 10 years since Rana Plaza. During Fashion Revolution Week, we are #RememberingRanaPlaza and demanding that no one dies for fashion. As we reflect, we are both inspired by the progress made in the Bangladesh Ready-made Garment (RMG) sector and reminded of the scope of human and environmental issues yet to be addressed in the global fashion industry.

What happened at Rana Plaza?

On 24 April 2013, the Rana Plaza factory building in Bangladesh collapsed in a preventable tragedy. More than 1,100 people died and another 2,500 were injured, making it the fourth largest industrial disaster in history. Rana Plaza was not the first or last garment factory disaster and was a symptom of the common problems faced by producer countries worldwide. Rana Plaza further exposed the widespread lack of transparency across global fashion supply chains, and how a lack of visibility can ultimately cost lives. Without transparency, issues remain hidden and unresolved at their root.

It is not by coincidence, but by design, that within the global fashion industry, garment worker wages are artificially low and that brands continue to source from regions where it is impossible, difficult and/or unsafe for workers to form trade unions and bargain for greater rights. The global fashion industry has continually relied on voluntary commitments which have allowed brands to continue with business as usual. A lack of living wages, freedom of association, collective bargaining, health and safety and traceability continue due to poor progress on transparency in these areas. A critical first step toward accountability, therefore, is greater transparency.

View this post on Instagram

What is the International Accord?

The Bangladesh Accord on Health and Safety (now known as the International Accord on Fire and Building Safety) was signed just weeks after Rana Plaza and is a landmark agreement that brought together brands, retailers, trade unions and supplier factories to address building and fire safety in garment factories in Bangladesh. It was the first time that global fashion brands acknowledged their direct responsibility for factory conditions in their supply chains – and 192 fashion brands are currently signed up.

The International Accord is the first legally-binding brand agreement on worker health and safety in the fashion industry. It was formed with the understanding that voluntary measures alone are not enough to address issues of health and safety because they lack transparency, enforceability and assurance of meaningful representation of workers and trade unions. The Accord is unique in being supported by all key labour rights stakeholders in Bangladesh and internationally, and being legally binding. It is the most important agreement to date to keep garment workers safe.

The Accord has three main goals:

- Promoting a culture of workplace safety by training Safety Committees and encouraging workers to identify, address and monitor safety hazards at factories.

- Preventing fire, electrical, structural, and boiler safety accidents through inspections and remediation programs led by specialist, independent engineers.

- Providing a trusted avenue for workers to raise safety concerns through an independent complaints mechanism.

This year, we pay tribute to the joint efforts of all Accord stakeholders who have significantly contributed to safer workplaces for over 2 million garment factory workers in Bangladesh, especially the global trade unions representing garment workers who were at the forefront of this ground-breaking agreement. You can find a list of organisations to support at the end of this blog.

You can read more about the International Accord via Clean Clothes Campaign and watch the below video which celebrates the measurable achievements of the Accord:

What is the Pakistan Accord?

In Pakistan, unions have taken the example of the Bangladesh Accord and are working to adapt it to their own national circumstances. Starting in 2018, labour organisations in Pakistan have been campaigning for a Pakistan Accord on Fire and Building Safety.

The Pakistan Accord is a legally binding agreement between global unions, IndustriALL and UNI Global Union, and garment brands and retailers for an initial term of three years starting in 2023. The factory listing of these brands would cover approximately 300-400 facilities in Pakistan. The program in Pakistan will include key features from the 2021 International Accord.

35 global brands and retailers have now signed the Pakistan Accord. Fashion Revolution stands in solidarity with all organisations who are calling on major brands and retailers to sign the Pakistan Accord and demands the industry protects progress so that a disaster like Rana Plaza never happens again.

Rana Plaza could have happened anywhere, as it was a devastating outcome within an industry rife with human rights abuses and environmental degradation. This disaster exposed that a lack of transparency costs lives. Whilst 48% of major brands and retailers included in the Fashion Transparency Index are disclosing their first tier supplier lists, supply chains remain complex, fragmented, deregulated and opaque with half of brands scoring 0-2% overall in the Traceability section of the report.

How transparent is the fashion industry?

Since Rana Plaza, there has been greater scrutiny on the global fashion industry and pressure for brands and retailers to be more transparent. The Global Fashion Transparency Index is one tool that Fashion Revolution has developed to help bring about systemic change in the industry.

The Index was created in 2017, recognising that a lack of transparency costs lives and allows human rights and environmental issues to thrive, unaddressed.Transparency alone wouldn’t have prevented Rana Plaza but without it, it is impossible for companies to make sure human rights are respected, working conditions are safe and the environment is protected without knowing where their products are being made. The aim is for this information to be used by individuals, activists, experts, worker representatives, environmental groups, policymakers, investors and even brands themselves to examine what big fashion brands are doing, hold them to account and work to make change a reality.

Our findings highlight an increased level of transparency over the last 5 years. In 2017, just 32% of 100 brands reviewed disclosed their first tier manufacturing lists. In 2022, 48% of 250 brands included in the Index now disclose their first tier manufacturing lists. Furthermore, in 2017, 0% of brands reviewed disclosed their tier 3 supplier lists. In 2022, 12% out of 250 brands included in the Index now do. While this progress is encouraging, it begs the question, what is still being hidden?

Ten years after Rana Plaza, there is still much to be done in the global fashion industry. Find out how you can take action and support organisations working on the ground in Bangladesh below…

How can I take action?

If you are a citizen:

- Call on major fashion brands and retailers to sign the Pakistan Accord. You can show your support by signing this petition and can directly lobby brands to sign by demanding action on social media or via email. Here is a list of brands who have and haven’t signed.

- Sign the Good Clothes, Fair Pay campaign if you are an EU citizen and, whether you can sign or not, help spread the word by sharing our posts on Instagram (@goodclothesfairpay) and Twitter (@goodclotheseu).

- Ask #WhoMademyClothes? and #WhoMadeMyFabric?

- Sign and share the Manifesto for a Fashion Revolution ahead of Fashion Revolution Week 2023.

If you are a policymaker:

- Support better regulations, laws and government policies that require transparency and corporate accountability on environmental and human rights issues in the global fashion industry.

- Be more proactive at responding to ‘red flags’ and risk factors associated with labour exploitation and environmental damage in the global fashion industry.

- Read and listen to the viewpoints of workers, communities and experts in the Global Fashion Transparency Index to inform your policymaking activities. Note that the views presented here are not exhaustive and we recommend seeking out and speaking with other affected stakeholders.

If you are a major brand and retailer:

- Sign onto the International Accord.

- Sign onto the Pakistan Accord.

- Publish your supply chain right down to the raw material level as soon as possible, doing so in alignment with the open data standard, and uploading the list to the Open Supply Hub.

List of global organisations to support

The following organisations have been central to the development and adoption of the International Accord:

Trade Union Signatories of the Accord

Witness Signatories of the Accord

- Worker Rights Consortium

- Clean Clothes Campaign

- Maquila Solidarity Network

- International Labor Rights Forum

International Accord Steering Committee Chair

Other organisations supporting garment workers in Bangladesh

- Bangladesh Worker Solidarity Centre

- National Garment Workers Federation

- Labour Behind the Label

- Awaj Foundation

- Remake

Header image: J Williams on Unsplash

Artículo redactado por Nora Sesmero Andrés, voluntaria de Fashion Revolution.

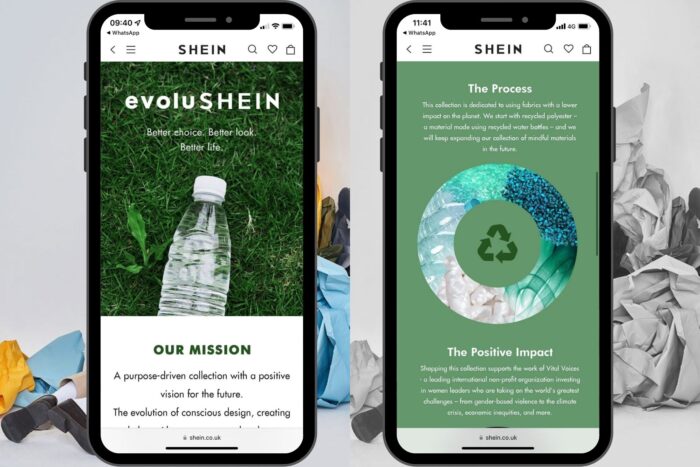

El greenwashing es una práctica de márketing destinada a crear una imagen ilusoria de responsabilidad ecológica y de sostenibilidad medioambiental por parte de una empresa. Según Vogue México, estas empresas usan términos como “consciente”, “orgánico”, “eco” o “sustentable” para definir sus productos aunque sus maneras sigan siendo abusivas y contaminantes. Un ejemplo de estas actuaciones son las marcas que pertenecen al fast fashion o moda rápida, las cuales llevan a cabo este greenwashing manteniendo una producción masiva que no resulta sostenible.

El ISEM Fashion Business School comunica que hay una parte invisible en la industria de la moda para el consumidor, esta corresponde con la cadena de valor de un producto. Aunque parece que actualmente los datos de este sector están dejando de ser invisibles. Algunas empresas han sido denunciadas por emplear greenwashing en sus campañas de marketing, como Inditex, H&M, Primark, Nike, Adidas, New Balance, Gucci, Dolce & Gabbana, Lacoste, Decathlon, Asos, Boohoo, etc., tal y como muestra el informe “Los numerosos lavados de reputación de la industria de la moda” de Carro de Combate, el Netherlands Authority for Consumers and Markets (ACM) o la Autoridad de Competencia y Mercados de Reino Unido (CMA).

El portal de moda sostenible, Vesti la Natura afirma que las fibras sintéticas se incluyen en más de dos tercios de los materiales usados en la industria textil. El material más utilizado es el poliéster, fibra que proviene del petróleo y que no es bueno que esté en contacto con la piel. A principios de año, Bloomberg publicó un informe donde se especifica que el 92,5% de la ropa estudiada de Shein contiene plásticos. La empresa lanzó la colección evoluSHEIN, que incluía tallas inclusivas y materiales sostenibles, esto se puede considerar como una acción de greenwashing.

De esta manera, algunas marcas realizan publicidad engañosa y tratan de confundir al consumidor. Entonces, ¿cómo puede detectar el consumidor el greenwashing? “La sostenibilidad está de moda y las grandes cadenas lo aprovechan para vender más. Cuando una empresa es sostenible de verdad tiene información amplia, contrastada y visible en sus webs. Creo que el mejor consejo es ser críticos y cuestionarnos, trataría de ser responsable con mi consumo. La insostenibilidad de la moda comienza en el volumen que se produce, mi consejo es tratar de analizar qué es lo que hay detrás de las empresas a las que solemos comprar, buscaría información sobre sus impactos medioambientales y sociales”, comenta la fundadora de Slow Fashion Next, Gema Gómez.

El consumidor tiene la posibilidad de informarse antes de hacer una compra, leyendo la etiqueta de las prendas y tratando de profundizar en la información que muestra una empresa. Cuanto más grande sea una marca, más difícil le será cambiar su estructura a una más sostenible. En el blog de Slow Fashion Next comparten que los usuarios podrían consultar si una organización hace donaciones en defensa del medio ambiente, preguntar qué procesos, requisitos o regulaciones ambientales están llevando a cabo o comprobar si forman parte de un Directorio que garantice que cumplen con un mínimo de requisitos.

La directora del máster en Comunicación, Gestión de Marca y Sostenibilidad en la Industria de la Moda de la Universidad Internacional de Cataluña, Elisa Regadera, explica que las redes sociales serán de gran ayuda en esta época, ya que harán posible que se le pidan explicaciones a las empresas ante las acciones que realizan. Además, tendrán un papel fundamental para tomar decisiones en favor del consumo circular: “Las RRSS son el lugar donde ‘vive’ la generación actual y ‘vivirá’ la futura”, afirma esta experta.

En los últimos años ha crecido la preocupación por el modo en que las empresas afectan a la sociedad a nivel social y medioambiental, y con ella, la necesidad de una comunicación transparente sobre la sostenibilidad. Pero, ¿cómo pueden contribuir las empresas a una comunicación auténtica sobre su compromiso con la sostenibilidad? Según la periodista y especialista en consumo y sostenibilidad Brenda Chávez, la clave para evitar el lavado verde es que los gobiernos regulen, las empresas dejen de utilizar estas tácticas y los consumidores sean conscientes de ellas para poder denunciarlas.

La industria y su impacto en el medio ambiente son temas que están en constante debate. Ante esta situación, Regadera plantea: “Considero que las condiciones de salud, seguridad y los salarios de las personas deberían ser el primer objetivo de la industria. Respecto a sus impactos en el planeta (cambio climático, recursos hídricos, ecosistemas, etc.), cualquier intervención para reducir el impacto en los procesos —desde el diseño y desarrollo de producto, la selección de materiales, así como todo lo relacionado con la fabricación, envasado, transporte, almacenamiento y distribución, consumo y devoluciones— produciría avances para combatir el cambio climático. Lo importante es trazar y conocer bien la propia cadena de suministro, decidir por dónde empezar y en qué se va a ser más responsable, aportando los datos con transparencia”.

Carro de Combate aconseja a las empresas evitar la exageración u ocultar información para hacer lavados verdes, creen que las compañías deberían defender cambios y demostrar soluciones a las personas, así como destacar y celebrar nuevos modelos a seguir. Vesti la Natura añade que estas deberían implicarse en la investigación de materiales de origen biológico y en una moda más circular, defienden que se tendría que abordar el problema de la producción de baja calidad y la moda rápida, que las marcas incluyeran además la obligación de adoptar la debida diligencia, tanto en términos de “derechos humanos” como de “violaciones ambientales”. Por último, plantean una pregunta a las grandes empresas: ¿Hasta cuándo seguirán haciendo afirmaciones falsas hacia sus clientes?

Gracias a la Ley 7/2022, de residuos y suelos contaminados que incumbe a la industria textil española, se están regulando nuevas medidas para que las empresas textiles se encarguen de sus desperdicios. “Las marcas deberán pensar en la donación, alquiler, reparación, venta de ropa de segunda mano, customización, etc. En el caso de no decantarse por estos nuevos modelos de negocio, deberán pensar dónde y cómo van a deshacerse, empaquetar y/o gestionar esos residuos, sin enviarlos a vertederos, otros países, etc. También deberían pensar en el ecodiseño, para no desperdiciar los restos de prototipos y demás. La tecnología también ayudará a poder introducir de nuevo en la cadena de producción aquellos tejidos que no estén mezclados y puedan dar lugar a nuevas prendas: reciclaje textil. Y por supuesto en cómo gestionar con sus proveedores las aguas residuales de fábricas, etc. Pero como la legislación obliga en el ámbito español y no siempre en los países de producción, esto seguirá estando pendiente”, comparte Elisa Regadera. En el marco de la COP25, Gabriela Figueiredo, presidenta del regulador portugués, señaló “la existencia de una guía a nivel europeo sería lo mejor porque los inversores tienen miedo del greenwashing. Este marco regulatorio tendría como ventaja el desarrollo de una información ‘entendible’ y ‘creíble’”.

Elisa Regadera introduce el pasaporte digital que “contribuirá a que las marcas sean transparentes en la trazabilidad de su cadena de valor a través del blockchain. Esto permitirá a las marcas hacer un seguimiento de sus procesos y detectar cualquier tipo de alteración, pudiendo corregir y/o hacer más eficiente su cadena. En los casos de marcas de lujo o artesanales, permitirá combatir también las falsificaciones. Y la misma información podrá ser conocida por el consumidor: a través de un código de barras, QR o algo similar adherido a las etiquetas o a las mismas prendas, tendrán acceso a toda la información. También podrá añadir otros contenidos relacionados con la marca, los cuidados de la prenda, eventos, etc. que se podrán consultar mediante este medio. Pero todavía queda un poco para que esta práctica se extienda, ya que pocas marcas tienen todavía acceso a la tecnología blockchain”. Figueiredo cree fundamental encontrar una solución “pragmática” para que este contexto no suponga una “avalancha” de información.

Parece que el greenwashing no desaparecerá próximamente, pero tanto consumidores como empresas podrán poner de su parte para hacer que esto suceda pronto. En los últimos años está creciendo el interés por parte del consumidor hacia la sostenibilidad y si su demanda crece, se regulará la situación.

Si te interesa seguir leyendo y concienciándote acerca de la actualidad de la industria textil, pulsa aquí.