MEET THE MAKER : Maria Pithara- Natural dyes in Cyprus. By Alexandra Pambouka, the Arts and Cypriot Tradition Leader of Fashion Revolution Cyprus.

Let us take you back in time, when Cyprus used to be a great destination of commerce and it was full of talented craftsmen who used 100% natural techniques to create fashionable garments.

We will focus on the story of natural dyes on the island, and we’ll meet Maria Pithara, a young natural dyer who chose to live in a small village in the mountains of Cyprus.

Unfortunately, the tradition of natural dyes of the island has not survived, but Maria and other young people on the island are trying to revive it.

The history of natural dyes in Cyprus.

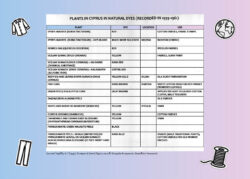

We got a lot of information in the publications by archaeologist Angeliki Pierides* (1918-1973). According to her book “Research on dyes and techniques, issued in 1959 and 1961”, local plants and seeds or animal derivatives (e.g. oxblood) were used for the manufacture of dyes.

Since the Middle Ages till the peak of the 18th century, Cyprus was well-known for the cultivation of the Rose madder (Rubia tinctorum), that gives the red colour, for local use and exportation.

In the 19th century the cheapest chemical Alizarine, replaced the rose madder.

Gradually all natural dyes were replaced by chemical ones and therefore the local know-how is not preserved

accurately.

Dyes were used for threads and fabrics.

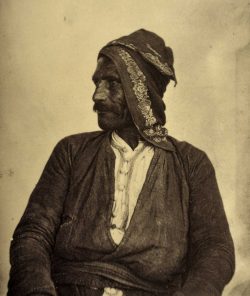

Pasmatzides, Mantilarades and Shalerenes…

There was a great variety of dyeing techniques.

In Nicosia, the “Pasmatzides” were male crafters dealing with the print of cotton fabrics (pasmades in greek) using wooden carved moulds-stamps, an art that can be found also in Greece, Istanbul and Minor Asia.

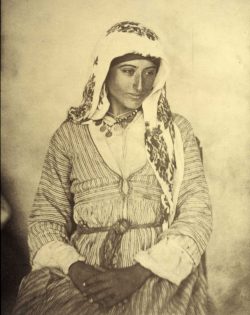

The “Mantilarades” were also male crafters, who used to print head scarves. They didn’t do the same technique as Pasmatzides, since craftsmen from the surrounding area came to Cyprus and influenced the local technique.

The complex process of making the dyes was undertaken by women.

The “Shalerenes”, in Kilani village, were female crafters, who used to dye silk scarves by tying thick knots on different spots. A craft similar to tye-dye.

At first, they dyed the scarf with Venetian sumach (Cotinus coggygria), which gives a yellowish colour. Afterwards, they tied the parts they did not want to be coloured and then deeped the cloth into the colour two or more times.

To finish them off, they undid the knots and various patterns were formed (Pierides, 1991 scarves, tying knots with silk slips (thick silk threads).

These scarves were called “eptaloitika” and the last artisan of them, passed away in 2005.

Maria Pithara, a young Cypriot natural dyer.

We met Maria Pithara during the festival Xarkis in Cyprus, where she facilitated a workshop about this technique.

Two years later, we visited Maria, in Treis Elies, a small village on the mountains of Troodos with very few inhabitants. She lives there and cultivates herbs and indigo with her family.

She told us about her relationship with natural dyes and sustainability.

Maria has always loved colour! She is a visual artist and started working on natural dyes, after a visit to the Metropolitan Museum in New York, at an exhibition on the global textile trade from the 16th till the 19th century. This is where she got her first manual about dyes and then started cultivating indigo. Since then, she never stopped learning and experimenting with natural dyes.

The natural dyes, which in the past had enormous commercial value, were gradually replaced by synthetic dyes.

According to Maria: “We know that many of the synthetic dyes used in the fashion industry are toxic, especially for the environment and people living around the factories, including the workers. Even we, who wear these clothes,

still don’t realize how harmful they are.

At the moment, it’ s not very easy to go back to natural dyeing on a large scale. It is very resource intensive (need for a large amount of land and water) and also the process of preparing and painting the fabrics is very time-consuming. Possibly, the solution is between nature and innovative technology, but research still needs to be done.”

As a mother, she worries about the environment that the younger generations are going to live in, and also about the indifference of many people (who insist on consuming recklessly, as she says) regarding the consequences of the environmental crisis.

Having that in mind, she supports a more sustainable living for her and her family in multiple ways. At first, she transmits the love for nature to families and children through workshops about the “magic” properties of natural colours. They explore the role of colors in the world of plants and animals and how to create dyes or paints naturally.

She believes that this is a way for the public to be more involved in the wonderful complexity of nature that surrounds us. She adds that:

“A child will not be able to understand the value of nature and therefore protect it, if it does not get in touch with it. She also believes that

“Art and creativity are the opposite of reckless consumption and should be encouraged from an early age”.

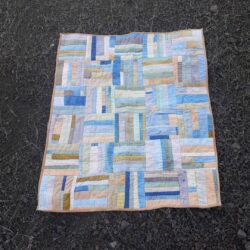

In her work, apart from the natural dyes, she reuses many fabrics, not only for sustainability reasons but because she has always been “attracted to the stories behind the old fabrics and clothes”.

What she would like to see is a change of our habits related to fashion: “I would like to see more people get dressed up and generally operate more consciously. To see them reject the easy, the fast and the cheap way of doing things. I don’t think you need to be rich to be sustainable. The simplest example when it comes to fashion is wearing second-hand clothes, which unfortunately many people avoid doing.”

What to be aware of when it comes to dyes.

According to Maria, what’s not entirely innocent about the natural dyes are the mordants (the agents which help the dyes attach to the fabric): “A few hundred years ago, when everything was dyed with plants/insects/minerals, dyeing was much more intensive, the dyers were using really high concentrations of mordants (much more that anyone today is using) and also the use of some of the more toxic mordants (such as tin or chrome) was much more prevalent than it is today.

The most common mordants used today are aluminum potassium sulfate and aluminum acetate,

which are metallic salts. Alum is generally not considered toxic, though one still has to be fairly careful when disposing it off, which means that it’s not entirely innocent. This is the mordant I use almost exclusively. It is a common practice to re-use your mordant bath (by continually adding mordant to the water) which reduces the frequency of disposals to a minimum.

Some of the younger natural dyers try to find ways to avoid mordants in general, either by using certain plants that don’ t require a mordant, such as indigo, or by using things like soymilk. The problem with the latter is that it’s a binder and not a mordant, so it doesn’t create a very good bond with the fabric and you don’t get very long lasting colours.

One very interesting story you might want to follow is that of symplocos, which is the only naturally occurring mordant available to dyers today. It’s a plant that grows in Indonesia and accumulates aluminum in its leaves from the soil.

There is a foundation which has tried in recent years to make the process of harvesting and trading more transparent and more sustainable, you can read about it here . I haven’t used it yet because it’s significantly more expensive than the chemical version of aluminum but I would definitely like to try it”.

You can find Maria at @rhusandparus and Alexandra Pambouka here.

Μπορείτε να διαβάσετε το άρθρο στα ελληνικά εδώ.

Book source: *Πιερίδη, Α. Γ (1991). Κυπριακή Λαϊκή Τέχνη. 2η εκδ. Εταιρεία Κυπριακών Σπουδών: Λευκωσία