Grow your own clothes: Developing natural dyes for our textile garden

This is a guest post from Kate Turnbull, natural dyer and Head of Fashion and Textiles Design at Headington, Oxford, who developed the natural dyes for the Textile Garden for Fashion Revolution.

Textiles, dyeing and printing are in my blood. My great grandfather John Tomkinson was the co-founder of The Premiere Dye Works in Leek, Staffordshire. He trained with the world-famous Sir Thomas Wardle, known for his innovations in silk dyeing and printing on silk and his collaboration with William Morris, who visited the Premiere to learn how to use natural dyes. During WW2, The Premiere were responsible for dyeing the uniforms for the British army and eventually sold to Dupont in 1970s.

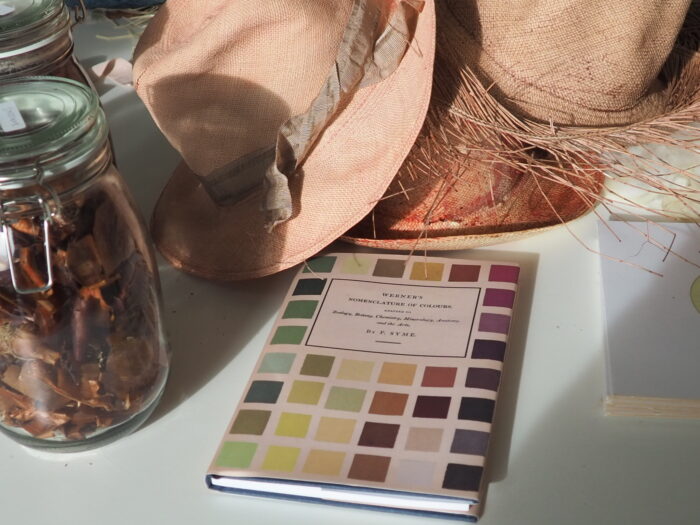

Growing up, I was always fascinated with this story, a fascination that grew when I found a copy of one of John Tomkinson’s prized dye books as an art student at which point I resolved to follow in his footsteps. I went on to train at Central St Martins where I first learnt about sustainable textiles and based my entire thesis on the damaging effects of textiles on the fashion industry and championing traditional silk screen printing methods for slow fashion. Sadly, John Tomkinson died aged 52 from lung cancer, most probably related to the chemicals used in the factory. (I turn 52 in July!) My mission is to pick up where he left off, but using natural dyestuffs and in my own small way both as a practitioner and an educator, to make a difference to the impact that textiles have on our planet.

Sustainable textile education

As an educator, my aim is to give the students the best grounding possible in sustainability and design. For many years there has been a growing realisation that the chemicals used in the classroom were both unnecessary and harmful, and as the awareness of the toxicity of the textile industry has grown, we felt it was time to shake things up in the Headington curriculum. It began with simple changes, such as embargoing aerosols, acrylic paints and synthetic materials and then through lockdown we were able to focus on how to re-engineer the course and maximise the potential for a comprehensive Eco-Textiles education. We began extracting and dyeing with colour from plants and making inks from berries and foraged botanicals. We now make all of our own colours to dye with, our own ink, glue and print pastes and we up-cycle old sheets to dye and construct garments with.

Recently – I am absolutely thrilled to report – all our hard work has been recognised, as I have been shortlisted in the TES School Awards as Subject Lead of The Year, which of course is recognition for the whole department as well as the students, who have embraced the course so wholeheartedly. Our brand new Eco Textiles cohort is thoroughly invested in both sustainable and ethical textiles, so much so that my dream of inspiring other schools to include this in their A-Level curriculum is beginning to feel tangible. Using this exciting spotlight on Headington, I hope I can reach out to other teachers interested in educating our young minds about the damaging effects of the Fashion and Textiles industry. Plus, one of the benefits of running the course like this, is that it costs so little in relative terms, making it accessible for everyone. We even have a gardening club where students from year 7 onwards sow and grow our very own dye plants.

The most exciting project of all is the opportunity the students have had to work with garden designer Lottie Delamain and Fashion Revolution, who have created A Textile Garden for Fashion Revolution, Chelsea Flower Show’s first-ever dye garden showcasing plant fibres that can be used to make clothing.

Why we need natural dyes

The production of polyester is an energy-intensive process producing high levels of greenhouse gas emissions, while wastewater emitted from polyester processes contain volatile substances that can pose a threat to human health. Despite this, Fashion Revolution’s Fashion Transparency Index 2021 found that only a quarter of major brands publish time-bound, measurable targets on reducing the use of textiles deriving from virgin fossil fuels. In my opinion, that is really not good enough and I hope that the symbolism and message of Lottie’s garden cuts through to the stakeholders and change-makers in the industry.

Lottie’s philosophy for the garden matches mine – it is about seeing the potential in the resources we have on our doorstep and exploring how we can utilise them in more creative ways as alternatives to synthetic, petroleum-based fabrics and chemical dyes. Many of the plants are native wildflowers, easily propagated and grown in the UK and undemanding in terms of water.

Bringing the garden to life

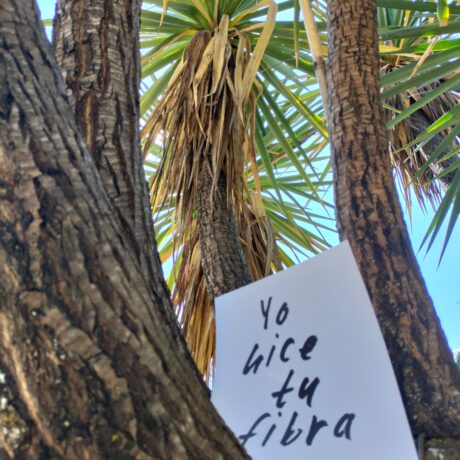

For the garden, my students and I have foraged and dyed linen panels, to be suspended above the dye plants in the garden. We have used different parts of the plant to demonstrate how versatile botanicals can be in terms of extracting colour. For the yellow panels, daffodil and dandelion heads were used. For the rust colour, rhubarb roots, for the pink cherry bark and madder roots (grown for three years in my garden for optimal pink) and for the green we gently simmered nettle leaves with a copper modifier. For the backdrop, we made a large 8m x 4m panel, hand-stitched together with reclaimed vintage Irish linen sheets. Lottie & I were keen to keep this in a simple grid-like formation, to reflect the Annie Albers influence of the garden. These were specifically un-dyed, to allow the panels to really sing out and to mirror the flax growing in her garden, which of course is spun and woven to make linen; a circular process.

Once the backdrop had been completed, I realised I had just enough linen left to make some garments, so I decided to hand dye it into three colours, one each for Lottie, Carry and me. I wanted the colour to be personal to each of us and, while I was pondering this, we received an exciting invitation to take part in the fantastic Wardrobe Crisis podcast, hosted by Clare Press. In the episode, our first question was to tell a ‘plant love story’. Lottie described how she had fallen in love with Cutch trees when she lived in Vietnam and Carry’s plant of choice was Weld, which she loves for connections to her Irish ancestry, for which she is writing a book about. I talked about ‘Sakura’ Cherry Blossom and the Hanami Festival I visited in Japan, inspired by the Threads of Gold Exhibition at The Ashmolean several years ago. I had my answer! Lottie’s linen was dyed in Cutch, Carry’s in Weld and mine in Cherry Blossom bark. I am lucky enough to be friends with slow Fashion designer Anna Mason. I contacted her to see if she would make up the fabrics into garments for us from her collection. She agreed! I can’t wait to surprise Lottie and Carry with the clothes they can wear to the Chelsea Flower Show, to demonstrate everything can be locally sourced, grown dyed and made for sustainable and ethical fashion.

After Chelsea Flower Show, the garden will be relocated to Headington, where it will become a permanent feature in the school and also have a working dye garden where students can forage for dye material for the Eco Textiles course as well as learn about gardening.

Further Reading

A Textile Garden for Fashion Revolution

Behind the scenes: Creating our textile garden at Chelsea Flower Show

The true cost of colour: The impact of textile dyes on water systems

Nature in Freefall: How Fashion Contributes to Biodiversity Loss