Tomorrow I will be joining eXXpedition to sail some 2000 nautical miles from the Galapagos to Easter Island as part of an all-female Round the World voyage to gather the first global dataset of microplastic and microfibre pollution. From Ecuador to Chile passing by Peru and Bolivia, we are sailing past the cultures and communities I studied for my MA in Native American Studies, and subsequently worked with for over 20 years with my brand Pachacuti.

The Andes mountains run down the spine of the Pacific coast of South America. Andean philosophy sees all individuals as being part of a community, an ayllu. Humans are not separated from the natural world; they are two parts of a whole, each dependent on the other and giving to the other through a reciprocal relationship which sustains the community. The ayllu does not have fixed physical borders but is formed from the complex interlinking of relationships and an understanding of the fundamental interconnectedness of my interests, your interests and the interests of plants and animals. The ayllu is a place of nurture and regeneration and is seen as the basic cell of life. People, plants, animals and the earth itself nurture and are nurtured in a symbiotic relationship.

In indigenous cultures around the world, and particularly within indigenous cultures in the Americas, it is common that nature speaks. Ecuador has drawn from its indigenous past and became the first country in the world to legally recognise the rights of nature in 2008. It has given nature back its voice.

Last week I talked to Zapotec textile artist and weaver Porfirio Gutierrez from Teotitlán del Valle, Oaxaca, who explained that in his culture’s traditional philosophies, the plants are just like us. His parents would take him up into the mountains to collect plants for dyes and his father would talk to him about how they needed to have respect for the plants and trees because they are alive, just like us, and no life is more important than the other. “These days when everything is fast, everything is chemical, everything is plastic, we are forgetting the principles of being a human being, the slow way of living, the growing of food, making a textile. To me it is really important to create a conversation around that and educate people, and re-educate people”.

As I worked on the research for this year’s Fashion Transparency Index, I saw company report after report, referring to the preservation of natural resources, but even in attaching the word resources to nature we are effectively commodifying the planet, protecting it to support ever-increasing productivity. When studying Quechua, I learnt that there is no word for possession in the language. You cannot say ‘I have’. Everything you have or possess – not just goods and resources but also power and authority – are instead either with you, or not with you, meaning you are the steward, not the owner. This way of thinking changes everything.

Our challenge this decade is to move beyond our currently destructive Western worldview which is tipping us into a climate crisis and a plastic pollution catastrophe, towards a fashion industry which integrates nature in a truly sustainable way. We need our legislators to learn from the law passed in Ecuador and restore a voice to the oceans, earth and all that live in and on them. We need brands and retailers to move from competitiveness to collaboration and from the commodification of natural resources to working alongside nature in all her diversity in a way that is respectful, renewable and regenerative. We need them to look at longer lasting value systems than profit, prioritising instead the protection of our ecosystems and the wellbeing of our communities. And as citizens who have lost touch with the reality of living in mutual nurture and interdependence with the natural world, we need to rebuild our connections with how our textiles and clothes are made, the slow way, in balance with plants, animals, earth and water.

I believe that transhistorical community value systems can present a powerful counterpoint to the logic of generating profit now and help us to once again rediscover the spirit of the ayllu.

Colour is a catalyst for sales success within the fashion industry; it is the first thing consumers notice about a garment. Before feeling the fabric, trying on for size, or considering the manufacturing processes, colour preference impacts the eye. According to Michael Braungart and William McDonough, on average, only 5% of the raw materials involved in the production and delivery processes is contained within a garment. It is therefore important that we also pay attention to the 95% of the material process that we do not see; a vast component of which is hidden water.

Thick, ink-like water flows through rivers surrounding garment factories; a toxic soup of chemicals discarded from the fashion industry’s synthetic dye processes, filtering into the water systems of the planet. Why is colour – this fundamental component of fashion production – allowed to pollute water systems throughout the world? As much as 200 tonnes of water are used per tonne of fabric in the textile industry. The majority of this water is returned to nature as toxic waste, containing residual dyes and hazardous chemicals. Wastewater disposal is seldom regulated, adhered to or policed, meaning big brands, and the factory owners themselves are left unaccountable. Examples of synthetic dyes are disperse, reactive, acid and azo dyes. Natural dyes, meaning colour obtained from naturally occurring sources – are another source of colour for textiles, but these are rarely employed on industrial scales.

Azo dyes are a commercially popular colourant for textiles. They are popular because they can be used at lower temperatures than Azo-free alternatives, and achieve more vivid depths of colour. But some are listed as carcinogens, and under certain conditions, the particles of these dyes can cleave (producing potentially dangerous substances known as aromatic amines). Upon contact with the skin, these can be harmful to humans and pollute water systems. Legislation exists in certain countries, including EU member states and China, that prohibits the sale of products containing dyes that can degrade under specific test conditions to form carcinogenic amines, but low traces of these amines have still been found in garments.

Natural dyes are a frequently suggested alternative, but like many brands guilty of ‘Greenwashing’ their processes, natural dyes on an industrial level give the impression of good behaviour, whilst introducing pollution problems of their own…

With production levels continuing to rise, and consumer demand for colour failing to diminish, alternatives to the current dyeing methods and regulations for water processing must be imposed.

HOW DOES THIS POLLUTION HAPPEN?

Much of the water used within production is utilised during the dyeing phase. Post-production water containing residual dye, mordants, chemicals, and micro-fibres is expelled into water streams untreated. This is frequently through pipes untraceable back to source, meaning factories can commit this offence anonymously. These hazardous chemicals do not break down as they enter rivers then oceans, making their way around the world.

In China, over 70% of the rivers are polluted (River Blue Documentary), meaning many of their 1.4 billion population cannot access uncontaminated water Ground water is contaminated, rendering wells unsafe for collecting water for domestic consumption. Billions of tonnes of wastewater are expelled from factories untreated, lowering dissolved oxygen within waterways to levels unable to sustain life. For the communities surrounding China’s Li River, and the factory workers handling these chemicals, exposure to toxic, potent and potentially deadly chemicals occurs on a daily basis.

WHO IS TO BLAME?

Western brands outsourcing the majority of their manufacturing are the main culprits, yet the impact of this devastating pollution is not experienced by the brands who perpetrate it. The rivers of high garment export countries are becoming unable to sustain life of any kind. Toxic to drink, an irritant when in contact with skin, and deadly to aquatic life, many of the rivers upon which communities rely are causing decreased life expectancies and increased health problems.

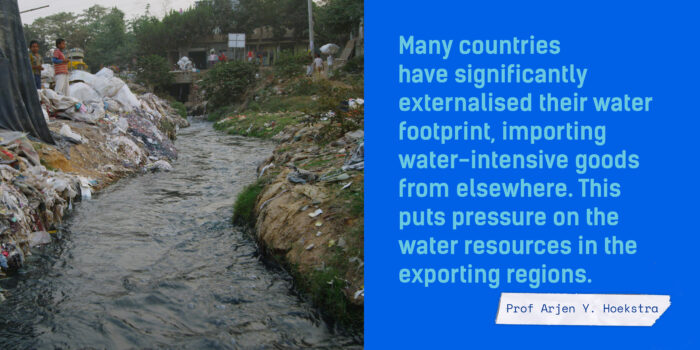

Professor Arjen Y. Hoekstra, creator of the water footprint concept explains the reality of the outsourcing of garment manufacturing to countries such as China and Bangladesh- two of the biggest exporters in the apparel industry:

“Many countries have significantly externalised their water footprint, importing water-intensive goods from elsewhere. This puts pressure on the water resources in the exporting regions”. In this way, the offenders continue to live with safe water and ever-expanding wardrobes, ignoring their far away trail of water devastation.

COULD NATURAL DYES BE A SOLLUTION ON AN INDUSTRIAL SCALE?

This debate is not a simple one.

Natural dyes are derived mostly from plants, seeds, fruits, barks, lichens and in some cases, insects. Though natural dyes have connotations of wholesome, toxin free textiles, this is not necessarily the case. Like synthetic dyes, they require a lot of water during production.

Though the dye materials themselves are not pollutants to water, the chemicals employed to fix the colour to the fibres are. These fixative chemicals are called mordants. Ground water and river pollution would occur if metallic compounds were used as mordants and not disposed of responsibly; the same problem synthetic dyes create.

SIDE NOTE ON CHEMICAL MORDANTS…

The term ‘mordant’, from the Latin term ‘mordere’, translates as ‘to bite’. This is a fitting name, as the objective of a mordant is to bond the dye with the fabric. Shades achieved with natural dyes are rarely as vivid as synthetic alternatives, and fade quicker from sunlight and wash cycles. Perspiration and PH levels of the skin can effect the colours achieved by natural dyes. The obvious remedy to this is the application of chemicals as mordants to fix the dyes and improve their longevity, vibrancy and resilience. But isn’t this defeating the object?

Whilst relatively harmless compounds can be used as mordants on domestic levels, such as sodium chloride (table salt), and diluted acetic acid (vinegar), when metallic salts are used things become more complicated.

Harmful and potentially lethal compound substances such as Potassium Dichromate (chrome), Stannous Chloride (tin), Copper Sulphate and Iron Sulphate are regularly used to achieve vivid shades with natural dyes.

Though the brilliance of these mordanted shades may be more commercial, these metallic substances effectively render the pollution free intention of natural dyes futile. It is possible to dispose of the chemically contaminated waste water safely, but this would require the same factory processing infrastructure that is currently lacking with synthetic dyes.

Without mordants, the colours achieved are more vulnerable to fading, potentially leading to shorter garment life. Indeed, these nuances in shade and the ever changing hues are arguably part of their beauty. The reality however is that whilst this is marketable where narrative engagement between consumer and textile lifecycles occurs, the fast fashion industry would unlikely engage with this.

Some natural dyes, known as Substantive Dyes, are high in tannins, which can adhere to fibres without the use of mordants. This is an area where small brands and start ups can utilise natural dyes, toxin free and enrich their designs with the narrative of sustainably produced colour. The history contained within natural dyes is an engaging consumer tool.

Many natural dyes are harvested from fragile environments, whilst agricultural land would also be necessary for production of industrial quantities of dye materials. Natural dye pigments only bond with natural fibres, meaning industries relying on petrochemical or regenerated yarns would not be able to use them. Best colour results are achieved on untreated protein fibres, with softer tones on cellulosic. Silk achieves vivid, sumptuous shades, but the silk industry is a point of animal welfare contention in itself. Therefore natural dyes create higher demands for raw materials, not just for the harvesting of dye sources, but for the processing of natural fibres. Treatments and finishes applied to natural yarns to improves fibre performance and extend garment life would also impact colour uptake.

Traceability in the supply chain of growing; harvesting and processing the raw materials present further issues. Indigo has a 5000 year history, from its beginnings as a dye stuff. Exploitation of the Indigo (blue) and Logwood (purple) trades was endemic in earlier centuries. Should natural dyes be employed again on industrial scales, the welfare of workers throughout the supply chain would have to be regulated in order to avoid the repetition of history. Sourcing from accredited suppliers and implementing strict regulations would be essential. As illustrated however, regulations across the fashion industry are inadequate and insufficient.

Important to consider too is the vast amount of land that would be required to grow enough natural dye stuffs to cater for the entire textile industry.

Natural dyes are therefore not a simple solution to the water pollution crisis but they do represent an important step. Different but equally important and challenging problems arise from their use.

WHAT DOES ALL THIS MEAN FOR THE FUTURE OF COLOURFUL FASHION?

The current textile dyeing systems are guilty of water pollution on a global scale. The waterways of our planet are ceasing to host life and endangering communities.

Factories claim costs of new infrastructure to process their water waste are too high, and with the fashion industry paying so little for their production to increase profit margins on their fast fashion, the factories are often unable to invest. Combined with this, a lack of education on the importance of the issue, and fundamentally a lack of care or compassion from the biggest brands contribute further to the crisis.

Putting pressure on brands for transparency in supply chains, and adjusting our expectations as consumers to purchase less and reject endorsement of fast fashion are ways we can individually make an impact. Green Peace’s Detox campaign has gone a long way in pressuring brands to reduce and remove chemicals from their water processes, but Greenwashing is still prevalent amongst many retailers; more must be done. Looking past colourful aesthetics to the morality behind the creation of our clothes will facilitate positive change.

***

Beth Ranson is a practice-based knitted textile designer and researcher in biodegradable fibres. Motivated by problem solving in circular, sustainable design contexts, Beth occupies the space between design and sustainability theory: and it’s an interesting space to be. As a specialist in the use of natural dyes, Beth researches the beauty held in their narrative, as well as their potential negative impacts on the environment.

Drip by Drip is the first NGO dedicated to solving fashion and textiles water impacts. Below, Drip by Drip’s Aurélie Rossini shares with us some of the key water issues driven by the garment industry in Bangladesh and how we can advocate for better water systems.

Water footprint, Water Scarcity, Water Crisis – Sound familiar?

If you haven’t heard these words before, now is the time.

If you think about it, 71 % of the Earth’s surface is covered by water. A number that has remained fairly constant over time, whilst the population has continued to grow. With that in mind, fighting climate change can’t happen without acknowledging that the world’s water resources are in crisis.

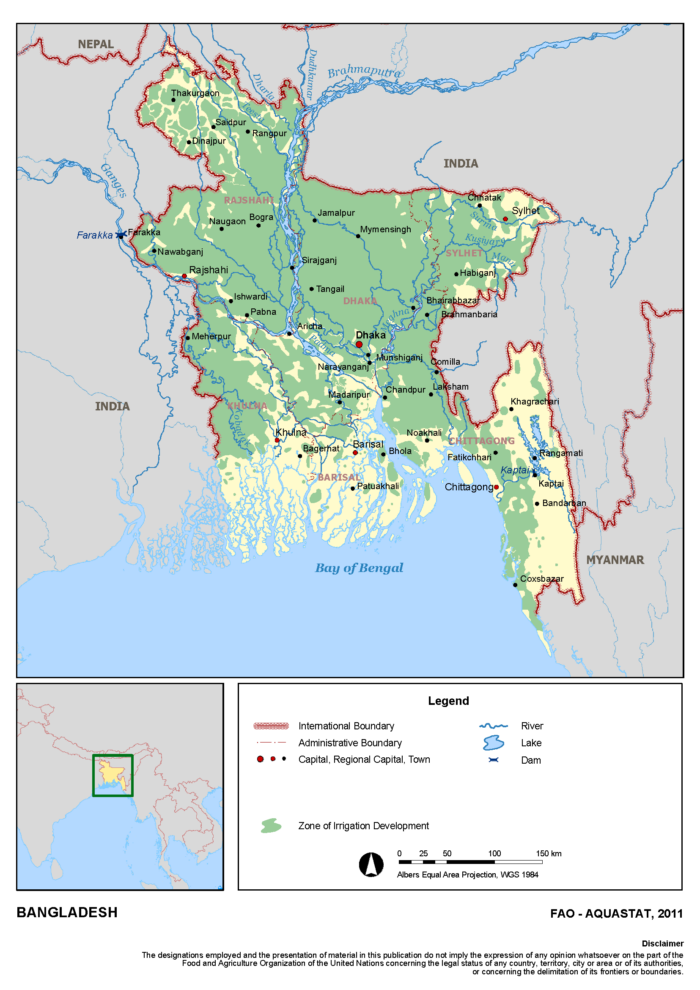

Water scarcity may be an abstract concept to you since water cannot be “lost”, but it is a harsh reality for others. In Bangladesh, the second-largest apparel producing and exporting country in the world, the rapid, unplanned and unregulated growth of the industrial sector is imposing increasing water stresses.

Bangladesh is one of the most vulnerable countries to Climate Change… but it’s also threatened by water scarcity.

At first sight, Bangladesh can appear as a country of water abundance. With more than 700 rivers flowing through its lands and an annual average rainfall of 2,000 mm, about 1,121.6 km of water crosses the borders of Bangladesh annually. Unfortunately, the country has to deal with great disparity as the availability of its water considerably fluctuates throughout the year. Moreover, the three main rivers (Brahmaputra, Meghna, and the Ganges) originate in other countries, thus the amount of water that eventually gets to Bangladesh is limited, leaving the Bengalis with little control over how much water they receive from these sources and in what quality.

The existing challenges imposed by the geographical conditions of the country place priority on water management. Unfortunately, declining groundwater levels, as well as deteriorating river water quality have increasingly been reported in the last decades.

Have you ever read on your T-shirt label that 2,700 L of water was used for its production? It is proven that the textile industry is heavily dependent on the water environment. Not only does it have an enormous water footprint in terms of agricultural consumption but also in terms of water pollution. In garment production, water is used for the cultivation of raw materials (cotton for example) but also in the manufacturing processes such as dyeing, tanning, printing, and washing. The nature of these processes involves high use of salts, dyes, bleaches, and chemicals, containing hazardous pollutants such as heavy metals. Effluents that are thereafter discharged without proper treatment into the rivers. It is estimated that over 625,000 tonnes of chemicals from the textile and leather industries enter the rivers every year. This number may be shocking for some, but it sadly is the true price of fashion.

Unregulated consumption and pollution – Two serious threats to natural water resources

Industrial wastewater in Bangladesh is significant: more than 4,000 MLD every single day, a number equivalent to 20,000 Olympic swimming pools!

Arsenic contamination of groundwater has been reported by many governments and donor agencies. Among them, the World Health Organization stated that “the levels of arsenic in Bangladesh have contributed to the largest mass-poisoning in history”, affecting an estimated 30-35 million people there.

Still, need more convincing facts?

It is important to note that 79% of industrial water – as well as most of the urban water supply – is sourced from groundwater with a substantial level of unrecorded industrial water abstraction. As a result, depletion of groundwater levels has been observed, with an average decline of about 3 meters per year. The heavy reliance on groundwater by the textile industry is consequently threatening domestic water use – and evidence shows a greater decline of groundwater levels in areas with textile clusters (e.g. the groundwater level in Dhaka has dropped by 10 meters per year during the years of 2000 to 2010).

As one of the most densely populated countries in the world, Bangladesh equally suffers from water scarcity. According to the 2030 Water Resources Group, if water demand for the textile sector does not decrease, it will result in additional water demand of over 6,750 megalitres per day by 2030. An amount that is impossible to source from the groundwater without risking the livelihood of the local population.

“Bangladesh needs foreign buyers and brands as much as they need Bangladesh”

In recent years, international brands have been under increasing pressure from their customers, shareholders and the public eye to improve the environmental and social compliance of their supply chains.

Water resources management in the textile industry is an important issue; an issue recognized by the Government of Bangladesh at the highest level. Textile trade associations have acknowledged the existing water issues, however, unless the risk of losing business increases, it is generally felt that there is little or no incentive to improve water management at factories.

So who shall we blame for the existing water pollution and scarcity in Bangladesh? Neither the economic system that values profit first nor the fashion brands alone. We’ve created Drip by Drip because we believe that players share a responsibility to guarantee the preservation of the national water resources. That is why we are on a mission to develop and implement innovative solutions to tackle the water issues in the fashion industry – from fibres over fabrics to production.

Our solutions for the industry

First and foremost, the responsibility lies with the textile industry to implement better water management structures such as central effluent treatment plants and closed-loop-systems. We are implementing tailor-made solutions, easily and cost-effectively integrated into factories to enable them to release the water back into the natural water cycle.

Together with our network of partners, we conduct research and perform training to help public organizations gain a deep understanding of the current situation. From our point of view, governments and public organizations have the potential to become game-changers here.

Our tool for consumers

You, me, us, as citizens, also play an important role. First, we can consider the water consumption in our wardrobe. Would you like to know your water footprint? Calculate it here with the first prototype of our Water Playbook!

Second, we have the opportunity to make informed purchase decisions: Choose clothes made from fibers that are less water demanding (for example, synthetic fibers like Modal or Tencel or rain-fed organic cotton) and look at where the fibers come from and prefer those that come from countries where water scarcity is not an issue.

You are now ready to make a sustainable change. We count on you!

Learn more on:

A new report by Changing Markets Foundation, ‘Dirty Fashion Disrupted’, reveals that while some fashion brands and leading viscose producers are making progress to clean up dirty viscose manufacturing, the majority of brands simply continue to talk about sustainability with no evidence of action.

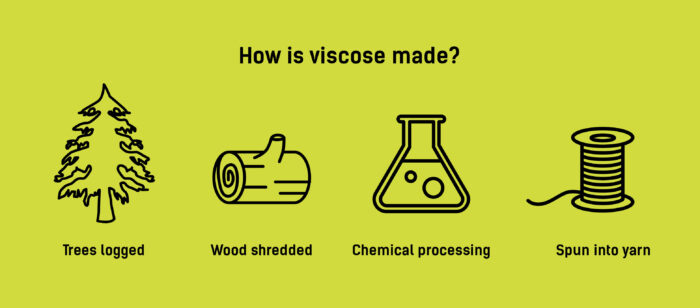

WHAT IS VISCOSE?

In simple terms, viscose is a cellulosic fibre which is made from wood pulp. This means that the material has a major impact on deforestation and requires a strenuous, and often heavily polluting, chemical process to turn the raw material (wood) into textiles for clothing. It’s this chemical production process that Changing Markets is trying to clean up.

Viscose is the third most commonly used fibre in the world and it has the potential to be a sustainable alternative to oil-based synthetics. Yet, previous Dirty Fashion investigations found clear evidence of viscose producers dumping untreated wastewater, contaminating waterways and ecosystems, and causing severe health impacts to local communities.

A toxic and endocrine-disrupting chemical, carbon disulphide (CS2), used in the viscose manufacturing process has been linked to serious health conditions, most notoriously as a cause of mental illness in factory workers but also a wide range of other conditions ranging from kidney disease to heart attacks and strokes.

DIRTY FASHION DISRUPTED

‘Dirty Fashion Disrupted’ assesses where global clothing companies and viscose producers stand in the transition towards responsible viscose. Through detailed scrutiny of 91 brands’ and retailers’ transparency and sourcing policies, and producers’ responsible production plans, the report examines the progress to date and gaps in existing commitments and pledges.

In August 2019, the Changing Markets Foundation – along with Fashion Revolution, Ethical Consumer, the Clean Clothes Campaign and WeMove.eu – reached out to over 90 global clothing brands and retailers, asking them for their most recent information on how much viscose they use, the details of any policies they have to address the environmental impacts of their viscose supply chain, the names and factories of their viscose suppliers, any plans to disclose these suppliers publicly in the future, and inviting them to commit to the Roadmap towards responsible viscose and modal fibre manufacturing.

SOME IMPROVEMENTS…

Many brands have shown a marked increase in transparency on their viscose supply chain. On their websites, four of the brands who have signed onto the campaign, Esprit, Tesco, M&S and ASOS, now publicly list the companies – down to the factory names – that provide them with viscose fibre. The remaining signatories (apart from Inditex), as well as several other brands, have disclosed the name of at least several of their viscose suppliers on their websites.

Orsola de Castro, Founder and Creative Director of Fashion Revolution commented:

“Transparency is visibility. We want to see the fashion industry, respect its producers and understand its processes. We want a clear, uninterrupted vision from origin to disposal to foster dignity, empowerment and justice for the people who make our clothes and to protect the environment we all share.”

STILL NOT ENOUGH ACTION…

The vast majority of brands are still lagging a long way behind the frontrunners on transparency. You can see which brands are taking steps towards more responsible viscose here: http://dirtyfashion.info/

Ten major high street brands and retailers have committed to take action on responsible viscose supply. However, luxury brands, including Prada, Dolce & Gabbana and Dior and low-cost retailers such as Walmart, Matalan and Boohoo, are failing to take action on polluting supply chains, devastating ecosystems and causing severe health impacts in local communities in India, China and Indonesia. It’s clear that the commonality among the laggards isn’t price point, but willingness to take fashion’s footprint seriously.

More than 25% of the brands investigated have no viscose policy in place, and many of these lack any environmental policy. Still, the Changing Markets has seen an increase in the number of brands responding to their questions and engaging with the campaign. For a full list of their findings, go here.

THE ROADMAP

In 2018, Changing Markets launched a Roadmap towards responsible viscose and modal fibre manufacturing to address the environmental and social problems in its manufacturing and provide a blueprint for responsible production for brands.

Ten major brands and retailers – Inditex, ASOS, H&M, Tesco, Marks & Spencer (M&S), Esprit, C&A, Next, New Look and Morrisons – have now made a public pledge to integrate its requirements into their sustainability policies. These brands are also expected to engage with their suppliers and use their leverage to drive towards more responsible viscose production.

Urska Trunk, Campaigns Adviser, Changing Markets Foundation commented:

“With increasing awareness of the environmental and social impacts of the fashion industry, people expect clothing companies to take responsibility for their supply chains. Brands and retailers can no longer turn a blind eye to this. They need to rise to the challenge and open their supply chains up to external scrutiny to put the industry on a more sustainable footing.”

WHAT CAN WE DO?

As citizens and consumers, we must use our voices to demand that fashion brands source materials in a transparent and responsible manner. It is unacceptable that over a quarter of the surveyed brands have turned a blind eye on viscose production that poisons people and contaminates waterways. Let’s ask #WhoMadeMyClothes? because we know that transparency is the first step in achieving a clean fashion industry that is safe for the wearers and the workers.

Tweet brands using the hashtag #dirtyfashion and ask them to be more transparent and move towards more responsible viscose here. Sign the petition to demand more responsible viscose here.

There are three things I have been passionate about over the course of my life: sailing and the sea, the indigenous cultures of South and Central America, and creating a more sustainable fashion industry.

Working with Pachacuti, the hat brand I founded over two decades ago, and at Fashion Revolution over the past six years, has brought together the latter two areas in many ways, but now I am incredibly excited to be able to draw all three of these strands together. In February and March 2020, I will be setting sail with eXXpedition to investigate plastic pollution and toxics in our oceans. Almost 10,000 women from around the world applied to take part in the two year voyage and I feel incredibly fortunate to have been selected to crew on the leg from the Galapagos to Easter Island.

I learnt to sale on the magnificent J-Class yacht Velsheda in the late ’80s and spent a few summers as crew before jumping over to the square rigged brig TS Astrid on which I spent many happy months sailing the Channel and taking part in the Tall Ships Race. I then worked on various boats in the Caribbean for a year and sailed across the Atlantic on the tops’l schooner TS Unicorn. I remember night after night on the seemingly pristine sea watching the glowing, glittering phosphorescence resulting from the bioluminescence of organisms in the surface layers of the sea (we took two months crossing the Atlantic so there were plenty of sea sparkle nights to enjoy!) I never imagined that I would be sailing the oceans again three decades later to carry out research into the degradation of the marine environment.

My Masters in Native American Studies at the University of Essex was the culmination of an interest in the Andean region which stemmed from somewhere far back in my childhood – I remember asking for a picture book about the Incas as a Christmas present one year when I was still quite young. I immersed myself in learning about indigenous cultures past and present and would have continued with my PhD on the symbolism of colour and natural dyes in the Andes. However, having set up Pachacuti in the summer holidays and seen at first hand the real difference fair trade could make to textile-producing communities in Ecuador, I decided to turn my interest in the region to more practical use.

One of the key concepts of the Andean worldview is ayni, meaning reciprocity and balance. Balance does not mean just a static equibrium; the Inca strived for the creation of an animated cosmos through a system of continual exchange based on mutual respect, justice, and solidarity. They saw reciprocity as the foundation for peace, resilience and enduring relationships with our environment and our community both near and far. Ayni was a continuous accompaniment to life in the Andes and the foundation on which society was based. Indeed, life itself can be seen as ayni.

If the equilibrium between communities and the natural world was altered, it could result in floods, or lack of rains. Andean peoples understood that ayni has to be recreated every day in order for regeneration to take place and, as a result, knew that they needed to give things up, to make sacrifices to restore balance. Reciprocity moves people beyond self interest in order to do something for the common good.

Perhaps it is not surprising that in 2008, Ecuador became the first country to legally recognise the rights of nature and two years later Bolivia adopted the Law of the Rights of Mother Earth. This means in practice that people can now sue on behalf of the ecosystem. The Ecuadorian Constitution says this will help to “achieve the good way of living, the sumac kawsay.” Nature is part of the social fabric of life, not a resource to be exploited. The Andean concept of good living or living well doesn’t mean living better than others, nor does it imply the accumulation of material wealth. It means living well together, with nature, with mutual support, with ayni.

I was reminded of this whilst on holiday this summer, in a chalet by the sea on Branscombe beach in Devon. I was working there with my daughter, Sienna, and we were discussing stakeholders for Fashion Revolution’s policy dialogue toolkits. She told me that we must make sure we include stakeholders who don’t have a voice like the ocean and marine life. It seemed so obvious once she said it and I was astonished I had never previously thought of including them. This just emphasised to me how far we have become detached from seeing our world as a living being.

Reciprocity is inherent in the way the earth works, although there are limits that are difficult to reverse once they are crossed, as set out in the UN United in Science report issued on 22 September. Our activities, our pollution, our degradation of the marine environment are stressing the earth’s natural capacity for reciprocity. If we are to tackle toxics and plastic pollution in our oceans, as well as climate change, waste, and the myriad other environmental issues relating to the fashion industry, we know that every choice and every action matters. If we want to see regeneration of our waterways and oceans which are essential for living well on this planet together, we need to take co-operative responsibility. The resources of both land and sea are a gift, and this gift requires reciprocity in order to maintain healthy ecosystems.

When I join eXXpedition and sail some 2000 miles through the Pacific Ocean, I will be taking part in groundbreaking scientific research on board this floating laboratory to help build a comprehensive picture of the state of our seas. I will also be helping to unravel how we got into this mess and how we can help shift our mindsets towards a more sustainable, a more balanced, future which encourages progress to a more regenerative system. The worldview of the peoples who inhabit the countries past which I will be sailing may well help us to find some of these solutions.

***

The eXXpedition Round the World voyage, which sets sail from Plymouth, UK on October 8th 2019, will sail through some of the most important and diverse marine environments on the planet. This includes crossing four of the five oceanic gyres, where ocean plastic is known to accumulate, and the Arctic on board 73ft sailing vessel S.V. TravelEdge. Under the directorship of award winning ocean advocate Emily Penn, 300 women will join the research vessel as crew over 30 voyage legs to journey more than 38,000 nautical miles. Follow news and updates via #eXXpedition @exxpedition on Twitter / @exxpedition_ on Instagram /eXXpedition on Facebook

I am looking for sponsorship and donations towards my participation in this groundbreaking voyage. Please see more information here – I am very grateful for any support.

Header photo: Soraya Abdel Hadi/eXXpedition

Neil Diamond’s ‘Forever in blue jeans’ nostalgia is an ideal which comes at a cost. Consistent colouration of recycled denim can be difficult to achieve and requires additional energy and water. Put bluntly, denim is decadent in its use of water.

According to Levi Strauss, 3,781 litres of water are used during the production and use phase of one pair of 501® jeans and 33.4 kg of CO2 is created throughout its lifetime. This includes growing cotton, processing the denim and washing at home. Minimizing these impacts requires producers to improve technology and consumers to think about how they care for their denim. To this end, MADE-BY created a wet processing benchmark that details the impacts from commonly used processing techniques and brings understanding and awareness to the impacts of this step in textile production.

Stemming from the insights of companies such as Jeanologia, MUD Jeans have developed an Ozone technology that can be used in place of water intensive stone washing, drastically reducing the water, energy, and chemical usage in the processing phase of jean production. The result is worn or faded looks without the negative environmental or health impacts. In Australia, researchers have created a way to make denim-dyed denim, with help from the H&M Foundation to scale and commercialise this technology to use recycled denim as a dye source.

In fact, MUD jeans was one of the first denim brands to build its business on sustainable principles and a pioneer in recycling cotton as well as re-using the water used in the dyeing process. Eva Engelen, responsible for CSR at MUD jeans, says:

“As a circular denim brand all MUD Jeans are made of at least 23% and up to 40% post-consumer recycled cotton, mixed with organic cotton. It is our goal to make jeans from 100% post-consumer recycled cotton and therefore step away from cotton cultivation. By using even more recycled cotton as a resource we will minimise our environmental and social impact further.

By using recycled cotton as a resource and making conscious product and production decisions MUD Jeans is able to obtain vast environmental savings. Each pair of MUD Jeans saves 5500 litres of water and emits 61% less CO2 compared with industry standards.”

Another denim brand to lead from the top is Wrangler.

“Innovation is at the heart of the Wrangler brand”, says Roian Atwood, Director of Sustainability for Wrangler. It started with the brand’s original innovations in 1947 and continues with their goals around water conservation and sustainable cotton.

Wrangler already leads the way in water saving and innovation , making it a central focus of their policy and research:

“Water use and wastewater are some of the biggest sustainability challenges in denim manufacturing, which is why we’re proud to have helped bring foam-dyed denim to our industry,” says Atwood. “We’re excited for other brands to follow in our footsteps, and virtually eliminate the water needed to dye blue jeans blue.”

Between 2007 and 2016, Wrangler saved over 3 billion litres of water in the finishing process alone and plans to save an additional 2.5 billion litres by 2020. After recognizing its potential to revolutionise the industry, the original rodeo workwear brand has developed a foam dye process which eliminates the use of water in the dyeing process. The innovation comes as Wrangler launch their Icons Indigood FW19 collection, this summer with a sustainable Indigo dye. Officially revealed to the press at their factory in Spain in early June, the team hail the collection as their “most sustainable jeans ever”. Eliminating their use of water in the dyeing process and using 60% less energy and making 60% less waste than conventional dyeing methods, the foam dyeing innovation will no doubt revolutionise this aspect of the denim manufacturing across the industry.

“This small collection is only the beginning”, the team states in the press release. “We’re working with denim mills in Asia and North America to bring this technology to a larger scale. Foam-dyed denim won’t just impact Wrangler’s supply chain, it will change our entire industry. We’re excited to be the the first brand to sell foam-dyed denim, but we’re even more excited that we won’t be the last”.

As regards the culture surrounding denim, Sean Gormley, creative director at Wrangler, whose Icon collection is also made from 20% recycled denim, says “we’re finding that buyers want to be able to give their customer a better, more sustainable product,” Gormley says. “Increasingly, you can’t call yourself a premium product unless your credentials are sustainable.”

Beyond cotton

If the DNA of premium denim brands is shaped by storytelling and heritage, then its lifeblood now depends on responsible innovation. Sustainability in fashion is no longer an ambitious idea, but a necessity, as shown by Levi’s innovation across its product lines, leading the charge with its Wellthread™ (sustainability-first) collection. Launched this year, the sustainably designed collection is modelled on four guiding principles: materials, people, environment, and process. For Spring/Summer 2019, those principles play out in a mixture of single fibres recyclability and value added through labour – cottonised hemp product.

The introduction of cottonised hemp is huge; not just for this collection but for the entire industry. Hemp crops require significantly less water to cultivate than cotton, with less than half the carbon footprint. However, the drawback with hemp to date has been that it’s a rough fibre, closer to linen than cotton. To solve this, Levi’s Wellthread™ collection has partnered with fibre technology specialists to develop a process to “cottonise” hemp, a method that softens the fibre—using very little energy or chemical processing—to make it look, and more importantly feel, almost indistinguishable from cotton.

“We know hemp is good for the environment, but it has always felt coarse,” says Paul Dillinger, VP of Product Innovation at Levi’s. “This is the first time we’ve been able to offer consumers a cottonised hemp product that feels just as good, if not better, than cotton.” The result is a casual and easy-going collection where every piece is fully recyclable —part of an ongoing collaboration with California surf brand Outerknown. Standouts include a Trucker Jacket and 511™ Slim jean made from cottonised Hemp blend (white colorway) and Refibra™ Tencel® denim blend (indigo colorway).

G-Star RAW has shown similar commitment to cleaning up cotton. Frouke Bruinsma , Corporate Responsibility Director G-Star RAW, says, “in 2006 we decided that sustainability needed to be integrated into the heart of our business and that’s when we officially started our Corporate Responsibility department. [… ] Because innovation is at the very core of our DNA, and sustainable innovations are naturally a part of that, we are actually always working on our next sustainable innovations and we see sustainability much more as an enabler to innovation rather than a hurdle”.

In recent years, G-Star RAW has launched capsules in numerous organic, recycled and nettle options as an alternative to regular cotton, recycling denim through post-consumer waste and launching a collection created out of plastic waste reclaimed from ocean shores. Speaking to me for this article, Bruinsma says “our biggest sustainable accomplishment to date is Our Most Sustainable Jeans Ever, which we launched last year, combining the cleanest indigo technology in the world, the most sustainable washing techniques, and using 100% organic cotton.”

She adds, “We were also the world’s first denim brand to collaborate with Archroma and create a collection of EarthColors® dyed jeans in 2017, a sustainable dye derived from recycled plant waste instead of petrol, traceable from earth to product. In July, we will introduce another range of EarthColors® styles including jeans, denim jackets, shirts, t-shirts and sweatshirts for both men and women.”

Raw denim – the benefits of mono fabrics

For the Slow Fashion movement, mono-fabric is always in style. While progressive, sustainable brands will no longer condone quick changing trends that create obsolete fashion on a monthly basis, champions of sustainable denim will be excited about a growing demand for mono-material jeans and raw denim. Heritage in style and spirit is making a comeback.

Raw denim is the godfather of all denim. It’s unwashed and characterized by its rigid structure and deep blue colour. In contrast, most of the jeans that we buy have been through a series of industrial washings to soften and add cosmetic effects to the trousers and add synthetics to improve stretch. Raw denim aficionados don’t wash their trousers for at least the first 6 months after purchase to develop a natural fade, custom-made by one’s own wearing. As you might have guessed, raw denim jeans need much less water in the production process, and the culture around raw denim lends itself perfectly to circularity. It’s all about retaining the value of the jeans for as long as possible through repair, re-wear and less washing.

Jade Wilting, Project Coordinator at the Circle Textiles Programme, says “we’re happy to see skinny jeans slowly making an exit from the wardrobes of the masses – if not for their unforgiving silhouette, then for their stretchiness, which is a major barrier when it comes to circularity”.

The movement toward non-stretch, rigid denim is a move in the right direction when it comes to circularity. It brings the history of denim right back full circle to its Western roots, of sturdy pants which could withstand hard work. Whilst paying homage to the labouring roots of our denim we take a look at those who work hard to bring us the jeans of today. Our final article looks at the democracy of denim.

The world is facing a number of unprecedented and urgent environmental crises. In January 2019 the World Economic Forum released its 14th edition of the annual Global Risks Report warning that we only have 12 years to stay under 1.5°C [1]. Rising temperatures will have a profound impact on the world’s water sources, including rising sea levels, higher risk of flooding and droughts, accelerating water scarcity, pollution, disruption of freshwater systems and more.

Water crises remain within the top ten risks to society [1]. 90% of the world’s natural disasters are water-related [2]. 2 billion people live in countries exposed to high water stress – population growth, increased water demand, and climate change are likely to exacerbate this [3].

When we talk about water crises, we consider three key dimensions:

Water scarcity – the abundance, or lack thereof, of freshwater resources

Water stress – the ability, or lack thereof, to meet human and ecological demand for fresh water; compared to scarcity, “water stress” is a more inclusive and broader concept

Water risk – the possibility of an entity (community, country, company) experiencing a water-related challenge (e.g. water scarcity, water stress, flooding, infrastructure decay, drought)

Image source: CEO Water Mandate

Water is a contextual issue, being both localised and impacting fashion businesses in different ways — through company’s direct operations, supply chains and sometimes both. This makes water a highly complex and globalised problem and one that can have significant positive impacts if solved.

Water-related risks in the global apparel sector

The apparel sector is particularly vulnerable to water-related risks because water is used throughout the production of raw materials like cotton and manufacturing processes such as dyeing, tanning, printing and laundering.

Cotton is currently estimated to be the most widely used material in the apparel industry [5], making up 33% of global textile production [6]. It is a very thirsty crop, with just one pair of jeans and one t-shirt comprising one kilogram of cotton and requiring an estimated 10,000 litres of water to produce [7].

China supplies 30% of the global cotton market and manufactures a vast amount of the world’s clothing. As a result, Chinese legislation has a huge impact on both the global economy and the planet’s ecosystems. Whilst China has adopted some of the strictest regulations on heavily polluting sectors including textiles and apparel, including its 13th Five-Year Plan for Ecological & Environmental Protection (2016-2020) and the Water Pollution Prevention and Control Law [8], it remains an important country in terms of water-related risks.

India and the United States are also large cotton producing nations, where droughts are increasingly prevalent. This can impact the global market in significant ways. For example, the last major spike in the price of cotton was in 2011, where the price per pound exceeded $1.90, up 150% from early 2010 [9]. The shortage of supply was in part linked to widespread drought conditions in China and the US. These rising costs put major fashion brands and retailers in a financially tricky position. They had to make a tough choice — they could either pass on the increased cost of cotton to price-sensitive consumers or absorb the costs in their already tight profit margins, i.e. the price of the raw material went up and so everyone along the chain potentially had to shoulder that cost.

Investors want to understand how companies are addressing water-related risks

Since then, the cotton price hasn’t reached such extremes but the impact to raw material costs remains a significant risk to apparel companies. That is why investors look to understand how well companies are preparing themselves for future price shocks triggered by water-related risks, amongst other factors. Effective water management in a company’s direct operations and across its supply chain is critical, particularly as global water resources become increasingly stressed. Good water management must include board level oversight of water-related risks and thorough water risk mapping processes.

River basins are important water sources for textile and apparel suppliers and their surrounding communities. If one company happens to be polluting the water basin upstream, the downstream residents may end up drinking and bathing in polluted and unsafe water and other downstream suppliers who rely on that river basin may be negatively affected.

Fashion companies need to understand who else is using the same water supply, what forms of agriculture rely on that water supply, whether the water supply is located in a densely populated area and what communities rely on that water source for their everyday needs. This is why fashion brands and retailers must effectively assess these risks and develop holistic water management strategies and systems, covering both direct operations and supply chains – though the supply chain is even more important, given that is where the majority of the risk lies for clothing brands.

Good water management practices are key

Companies should be setting targets for improvements in water management practices, monitoring progress and disclosing the results of their efforts in consistent and comparable ways [10]. This is the only way that fashion brands and retailers will do their part towards achieving targets 6.3 [11] and 6.4 [12] of the SDGs, which aim to improve water quality, increase water-use efficiency and protect water-related ecosystems.

This article was kindly contributed for our online course, Fashion’s Future and the Sustainable Development Goals by Emma Lupton from BMO Global Asset Management. To find out more about Emma’s work, please visit the BMO website

References

- WEF. Global Risks Report 2019. 14th Edition. 2019. Available at: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Global_Risks_Report_2019.pdf

- UNISDR. The Human Cost of Weather-Related Disasters 1995-2015. 2015. Available at: https://www.unisdr.org/2015/docs/climatechange/COP21_WeatherDisastersReport_2015_FINAL.pdf

- UN Water. SDG6 Synthesis Report 2018 on Water and Sanitation. Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters. 2018. Available at: https://www.unwater.org/publications/highlights-sdg-6-synthesis-report-2018-on-water-and-sanitation-2/

- CEO. Water Mandate, Understanding Key Water Stewardship Terms. 2019. Available at: https://ceowatermandate.org/terminology/

- FAO. Profile of 15 of the world’s major plant and animal fibres. 2009. Available at: http://www.fao.org/natural-fibres-2009/about/15-natural-fibres/en/

- FAO. World Apparel Fibre Consumption Survey 2005-2008. 2011. Available at: http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/est/COMM_MARKETS_MONITORING/Cotton/Documents/World_Apparel_Fiber_Consumption_Survey_2011_-_Summary_English.pdf

- Mekonnen MM, Hoekstra AY. The green, blue and grey water footprint of crops and derived crop products. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci. 2011;15(5):1577–600.

- China Water Risk. Today’s fight for the future of fashion: Is there room for fast fashion in a Beautiful China? 2016. Available at: http://www.chinawaterrisk.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/China-Water-Risk-Brief-Todays-Fight-for-the-Future-for-the-Future-17082016-FINAL.pdf

- Financial Times. Cotton prices surge to record high amid global shortages. 2011 Feb 11. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/3d876e64-35c9-11e0-b67c-00144feabdc0

- CEO Water Mandate. Exploring the case for corporate context-based water targets. 2017. Available at: https://www.ceowatermandate.org/files/context-based-targets.pdf

- Sustainable Development Goal 6 Clean Water and Sanitation, Target 6.3; By 2030, improve water quality by reducing pollution, eliminating dumping and minimizing release of hazardous chemicals and materials, halving the proportion of untreated wastewater and substantially increasing recycling and safe reuse globally.

- Sustainable Development Goal 6 Clean Water and Sanitation, Target 6.4; By 2030, substantially increase water-use efficiency across all sectors and ensure sustainable withdrawals and supply of freshwater to address water scarcity and substantially reduce the number of people suffering from water scarcity.

It used to be the case that ‘sex sells’. From the perfume industry, to cars, chocolate, footwear and especially jeans, appealing to our primal instinct used to be a sure-fire sales strategy. But in an age of conscious consumerism, a commitment to sustainability and an interest in the story behind a brand is starting to take precedence.

We love our denim, so much so that the average consumer buys four pairs of jeans a year. In China’s Xintang province, a hub for denim, 300 million pairs are made annually. Just as staggering is the brew of toxic chemicals and hundreds of gallons of water it takes to dye and finish one pair of jeans. The resulting environmental damage to rivers, ecosystems and communities in China, Bangladesh and India is the subject of a documentary called The RiverBlue: Can Fashion Save the Planet? The question as to #WhoMadeMyClothes has now entered mainstream conversation and few items of clothing are more mainstream than a good old pair of blue jeans, right?

Whether it’s mass produced cotton, water pollution, excessive consumption of water, denim sandblasting and dyeing or poor working conditions, the wholesome image of the denim jean has masked their negative impact on the environment. However, the industry is evolving with this shift in consumer sensitivities as it reflects a more mindful generation.

Denim has always said something about the times in which we live and if ever the fashion industry needed proof of the power of storytelling to sell clothes, then Levi’s is it.

From inventing the blue jean back in 1873 to staying true to its philanthropic values – in 1897 founder Levi Strauss provided the funds for 28 scholarships at the University of California, all of which are still in place today – Levi’s has built a brand based on innovation and social responsibility, remaining authentic by not only refusing to compromise on these values, but also by using them to grow the brand. Founded in 1853, the US denim giant was valued at $6.2bn (£5.3bn) when it floated on the New York Stock Exchange earlier this year.

A name synonymous with jeans themselves, the American brand has navigated over 160 years of retail by adapting a strategy of product diversification, expansion in direct-to-consumer business and a better connection with consumers worldwide. It’s listened to its customers and reflected the times in which we live, while never losing touch with its heritage. “As a brand, Levi’s has always been more about its future than its past” Nicola Kemp, trends editor at Campaign magazine.

So what is the future of Levi’s and indeed of the denim industry more broadly? Manufacturers, brands and small denim upcycling businesses are revolutionising the culture and production of jeans and making great strides to change the way in which cotton plays it part, closing the loop in the life of a pair of jeans.

The business of denim

In April, the Kingpins trade fair, held in Amsterdam, brought together industry professionals, showcasing the latest trends and innovations to hit the world of denim, an epicentre for the denim industry and its future.

This year the show increased its ethics and sustainability focus by introducing new requirements for all its denim supply chain members after noticing that few had made serious progress toward improving CSR standards.

The new programme, which will require all exhibiting denim mills to meet new standards in corporate social responsibility (CSR), environment and chemical usage, it will be expanded to its New York, Hong Kong and China shows. It’s a seismic shift from the top.

“In social compliance we have found that virtually none of our denim mills have an SA 8000 certification or a WRAP certification – which is disappointing,” founder of Kingpins, Andrew Olah, said in a statement.

Speaking at the event, Tricia Carey, director of global business development for denim at Lenzing, said “sustainability will no longer be a trend – it will be embedded in the supply chain.”

Indeed, love and sustain the lifespan of a pair of jeans is now the spirit driving all the innovators from small repair and upcycling workshops through to vertical chains such as H&M and pure denim brands themselves.

Rebecca Larsen, product development manager at House of Gold, the agency which homes denim mills Blue Diamond, In the Loop, and Jeanious Laundry, said that more focus will be put on creating a circular denim industry. “Sustainability is important but it’s not enough. What really needs to happen is we need to close the loop. Instead of constantly producing more and more, we need to learn to reuse what we already have.” The trend of the 4 Rs – repair, recycle, reuse and reduce – will likely continue to rise in the next ten years, according to Larsen.

When it comes to overseeing each stage of the product cycle, central control is crucial meaning that vertical integration has come to play a key role.

Premium brands buying supply chains and passing on skills is a trend that seems to be growing in popularity since vertical integration allows brands to attain a higher level of quality control over factors such as waste, water, chemical and recycling management.

High Street heroes

Inspired by their presentation at Fashion Revolution’s Question Time, held at the V&A in April, I spoke to H&M’s sustainability expert Mattias Bodin and asked him where denim sits in their much-heralded sustainability policy.

“H&M Group doesn’t have a specific sustainable denim policy. Instead, our policies cover all our products and production processes, as well as for denim”, he said.

Indeed, the Swedish group’s Sustainability Report has already set the bar high for other high street vertical players.

“One of our sustainability goals is that all the cotton in our range should be recycled or sustainably sourced by 2020 at the latest: organic cotton, recycled cotton or cotton sourced through the Better Cotton Initiative (BCI). And we are almost there — sustainably sourced cotton represents 95 % of the cotton we sourced in 2018. We also support screened chemistry and are members in ZDHC.”

H&M rank all denim according to Jeanologia’s tool EIM (Environmental Impact Measurement), “30.8% of our denim products have achieved a green level EIM which means they used a maximum of 35 litres of water per garment during the treatment processes.”

Last autumn, H&M group’s Monki brand reached its goal to source 100% of its cotton products sustainably. Monki’s sustainably sourced cotton includes organic cotton, recycled cotton and Better Cotton sourced through the Better Cotton Initiative. Likewise, their Weekday label has also reached their goal to use 100% sustainably sourced cotton (2018), in their case, meaning organic or recycled cotton, in their denim and basics range.

Reflecting the industry’s interest in moving away from cotton more generally, Bodin adds “we’re also looking into new ways to incorporate more recycled fibers as a substitute for cotton.”

It’s clear to see denim is a big part of all our wardrobes, and as such a specific niche of the fashion industry brands, designers and manufacturers have the opportunity to really focus and lead in it’s development. We see Levi’s are looking to close the loop, Kingpins are encouraging brands to improve standards and H&M are looking into improving the raw material and this is a great step in the sustainability of of planet. However the overall message seems to be buy once, care and repair, made better but prolong the life. Next week we will release The Future of Denim, Part #2: the 3 R’s – Re-use, Re-pair, Re-cycle to see who’s innovating in extending the life of our denim.

In its Statement on Copenhagen Fashion Summit 2019, published after the CFS publicised its programme on May 5, the Union of Concerned Researchers into Fashion questioned some of the language and continued assumptions made by much of the industry around sustainability. When industry leaders get together to talk about what they are doing to solve problems, there is a tendency to oversell ideas, to gloss over statistics, to make grand statements, and to pat themselves on the back for the slightest progress. While the Copenhagen Fashion Summit celebrated its 10th year of ‘rewriting fashion,’ there is no doubt that the industry is still working from the same notes it has always used.

As the UCRF wrote in its statement designed to bring a sense of perspective to the summit, “when we take the long view and examine fashion and sustainability progress over the last 30 years, we see that we have not come far at all. Certainly today there are more players and more organisations, more spectacles and celebrations, but not actual advances in ecological terms. So far, the mission has been an utter failure and all small and incremental changes have been drowned by an explosive economy of extraction, consumption, waste and continuous labour abuse.

“We would encourage people engaging with the agenda of the Copenhagen Fashion Summit to pay attention to terms such as “sustainable growth”, which in almost all cases is an oxymoron. While it is a term favoured by investors and asset managers, it is important to stress that the industry has spent 30 years trying to fix the old system, and it is getting worse, not better.”

Measurable progress has slowed down in the last 12 months

Sobering words. So as the Fashion Summit began with opening remarks by Denmark’s Crown Princess Mary, there was nothing to applaud, and little to celebrate. The Global Fashion Agenda’s report The Pulse, reported that the progress the industry is making in terms of its environmental impact has slowed by a third compared with the growth of the sector. Which means if it continues as it is, it will continue to be a net contributor to climate change.

With cheap labour continuing to prop up an industry that still clings to volume, speed and margins as the main drivers to success – despite the fact that consumers are demanding that brands increase their positive social and environmental impact.

There were, however, many positive and useful moments during the summit. The majority of the 1,300 strong audience that attend the CFS because are curious, they want answers, they want to make a change. They know that the campaign for a more sustainable fashion industry has been going on for over thirty years – it didn’t start with this summit. And they are active citizens who question everything. For every CEO on stage calling for ‘strong leadership’ and advocating circularity without addressing the elephant in the room which is consumption, there were hundreds of conversations going on around the fringes, exchanging ideas, making connections, hoovering up scraps of information to take back to their NGOs, their brands, their publications and companies to change the way they work and make sure it is not business as usual. It is the chance encounters with a community who have gathered because they are united in a desire to create a different sort of fashion industry which are the most lasting and important.

Made in Ethiopia

The most enlightening conversations were not necessarily those on the main stage. Taking a coffee break away from the panel discussions, I happened to sit next to Dorothée Baumann-Pauly from NYU Stern Center for Business and Human Rights. I wasn’t aware of the event she had hosted the night before the summit to publicise the report she has co-written Made in Ethiopia: Challenges in the Garment Industry’s New Frontier. The report investigates the nascent garment production hub which currently employs 25,000 workers at an industrial park 140 miles south of Addis Ababa. It’s an initiative started up by the Ethiopian government to attract the global fashion industry – including many brands whose CEOS and sustainability and supply chain officers were on stage, H&M, Tommy Hilfiger, Calvin Klein among them – to manufacture in the country. The chief attraction? No, it’s not state of the art factories, well-resourced creches, safe transportation, regulated working hours, or the guarantee of a living wage. The major incentive surely is the lowest wages of any garment-producing country. A basic wage of $26 per month – well below Myanmar, Bangladesh and Cambodia – mean that none of the above apply.

Dorothée pulled out a copy of the report and it makes for fascinating reading. It outlines how PVH, the conglomerate that owns Tommy Hilfiger and Calvin Klein with nearly $9.7 billion annual revenue, were looking to shift its manufacture away from Bangladesh after the Rana Plaza disaster. They were attracted by the country’s “green” power potential and the possibilities of a fresh start but two years after the opening of the Hawassa industrial park, things are not going as planned. The report makes recommendations to the Ethiopian government as well as to western brands manufacturing there. Now, this is a discussion I would have been keen to hear on the main stage at the summit.

PVH’s Chair and CEO Emanuel Chirico was on stage on day two. Sure, I was really interested to hear about their plans to make three of their best selling items – the dress shirt, underwear, and the T-shirt – recyclable as part of a circular system which can be returned in store and remade into new product. But I’d really love to hear how they are dealing with the issues at their new factory in Ethiopia. Challenges like this are the issues that need to be shared for everyone to learn from. The only time I heard Ethiopia mentioned was from Nazma Akter, the trade unionist and one of the few representatives at the summit of the garment workers. She said she was just back from a trip to see the conditions in Ethiopia and that she was shocked by what she had seen. And from her own perspective starting out as a garment worker in Bangladesh as a child, she has seen some shocking working conditions. A conversation between Ms Akter, Ms Baumann-Pauly and Mr Chirico might have even resulted in some actual change happening on the ground. So that seemed a lost opportunity. Instead, we sat and watched the screen and sighed.

We have eyes but can’t see

There were some other moments of real clarity, positive progress and stop-you-in-your-tracks brilliance. Paul Polman, Chair International Chamber of Commerce and The B Team, gave some home truths that really resonated about actions speaking louder than words. “The worst thing is having eyes and not be able to see: this is where we are at now,” he said. It was a sentiment echoed by Anindit Roy Chowdhury, Programme Manager for Labour Rights, C&A Foundation. “To say that we don’t know is not good enough. It’s unacceptable that none of us truly know if there is or isn’t child labour involved in the clothes we wear,” he said. “And we must invest in transparency.”

Experts and facts are needed more than ever to reiterate the stark truths about climate breakdown and the crisis we find ourselves in. Dr Martin Frick, senior director for policy and programmers coordination UN Climate Change told us: “the house is on fire, we are coming into a feedback loop where climate change is accelerating.” Time is running out.

Fashion, he said, contributes roughly 10 per cent of global CO2. He called for “radical co-operation between brands competing for a market share.” He also called on the industry for its ability to capture hearts and minds and influence behavioural change. “Fashion runs on the biggest source of renewable energy there is – human creativity.” The fact that the launch of the UN Fashion Industry Charter for Climate Action by Stella McCartney was one of the most publicised events at COP24 in Katowice in December demonstrates the power fashion has to get the message out. It is clear that we can harness the extraordinary influence we have to influence people’s consumption habits and choices in a way that all the experts and scientists in the world (David Attenborough not withstanding) can’t.

Another expert from outside of the fashion industry was Philip Lymbery, CEO of Compassion in World Farming, and author of Farmageddon: The True Cost of Cheap Meat who said, the only way forward for agriculture is to make it regenerative – and we must cut the number of cows being farmed by half if we are even to begin to redress the balance. “If we continue as we are, the UN warns we have only 60 harvests left,” he told us. “Then what? No food. No fibre. There’s a new game in town. Sustainability is over – sustainability is about doing tomorrow what you can do today.”

Technology and disruption

There was much talk about technology. Avery Dennison launched 10 solutions including a patent to use recycled materials in its labels. They are working with Plastic Bank to recover plastic before it reached the oceans and use it in their recycled and recyclable labels.

They also presented a project with 1019 ALYX 9SM using blockchain technology powered by EVRYTHNG to create a product that can tell its own story from the factory to its onward journey when it is eventually resold and the next buyer can see from the label’s scannable information that it is ‘authentic’ product, so addressing one of the industry’s other great issues of counterfeiting. Admittedly, the brand can control what information it chooses to release to the consumer (and what not to disclose) but it is a real step along the way of being able to ask – and answer Who Made My Clothes? It’s still at proof of concept stage but will be up and running later this year with the aim of allowing every garment to have its own digital i-D which will allow brands to track how much stock they have and – in theory – produce less as well as giving citizens the ability to track their garments at every step, including while they are in their care.

The world of digital traceability is a hot topic. Google announced its partnership with Stella McCartney to track the environmental impact of cotton and viscose. By pulling together data from a wide range of sources – NGOs, brands, manufacturers, and academics – they hope to stitch all the available data together to reveal the hidden environmental costs of the industry’s most widely used materials.

There were other companies working to make supply chains more visible – and standard practice – for consumers to access on the shop floor. The garment tag will become the key to a whole world of information designed to help concerned citizens make the best choices if they need to buy a new item of clothing. TrusTrace is an 18-month old start-up based in Stockholm where it benefits from the Swedish government’s innovation fund (other governments, please note!). One of the founders, Saravanan Parisutham told me how he had been inspired to start his business after the realisation that his father’s coconut farm in south India was being fed contaminated water. He said the water in the wells and rivers, used to irrigate the coconut farms, was being contaminated by local dyeing units. “The system accepts multiple levels of certification,” he explained. TrusTrace is already working with 1200 suppliers worldwide, in 20 countries. The 25 brands who pay to use the service include, Vaude and Filipa K.

Designers can’t do this on their own

One of the criticisms from the UCRF was that fashion designers do not necessarily have the power to make decisions about material sourcing and production processes and assuming they do lets business leadership off the hook. That message is getting through to some brands who are joining the dots. Noel Kinder, Nike’s Chief Sustainability Officer talked about using waste as a ‘feedstock for new products…you have to start from the very beginning,” he said. Designers, supply chain officers, finance officers and CEOs all need to be united in their efforts to change the supply chain, materials and entire production systems. However, Christopher Raeburn, who recently took over as creative director at Timberland as well as running his own brand Raeburn, emphasised the importance of creative directors having a strong vision: “It’s our obligation as creatives to think about the products we create,” he said. “This isn’t a trend. We need to fundamentally change what we do as an industry.” He added that access to more sustainable materials has really shifted and stated that “transparency on every level” is key.

The voice of the youth – and the desperate need for greater inclusivity and diversity

The most clarity however, came from the Youth Summit, brought together to imagine a fashion industry that is built around Sustainable Development Goals 3 and 5. They came up with eight demands which you can read here (just to give you an idea of the tone, no. 5 starts with “We are done with your bullshit”). Their demands are for an industry that is based around core values of empathy, transparency, collaboration and equality.

“Look around and see whose voices you are missing…After 10 years of Copenhagen Fashion Summit, we still don’t have equality in the fashion industry,” said student activist from Cornell University, Hansika Iyer. “We are the future and we want to act now!” she told the audience of industry leaders. The anger and the frustration was palpable.

If real, systemic change is to happen with the urgency it needs, the sooner the next generation take control and relentlessly tackle the crisis of waste, spiraling levels of consumption, over production, labour abuse and inequality, the better. Forget profits and bonuses. The incentives driving the entire industry forward should be the goal of zero carbon emissions and other greenhouse gases. As we see from the past 10 years this generation of leaders has spent talking a lot, but not actually achieving very much, there’s a colossal amount of work to be done.

As Katharine Hamnett, who has been talking about the environmental impact of the industry for three decades said, “we’ve got to get our shit together.” It was time to act 30 years ago. Unfortunately, not enough people were listening back then. Emanuel Chirico said that it was “another world” ten years ago. Well, it wasn’t. The house was on fire back then, but the industry wasn’t interested. Industry leaders need to take responsibility for their inaction and complacency. At least now, eyes and ears are fully open and with enough will and urgency, we can all do our bit to put out the flames.

In June 2018 the Environmental Audit Committee launched an inquiry into the Sustainability of the Fashion Industry.

They wrote to sixteen leading UK fashion retailers asking what they are doing to reduce the environmental and social impact of the clothes and shoes they sell. Today they release their Final Report: Fixing Fashion: Clothing Consumption and Sustainability. Within the report are key recommendations that the EAC hopes parliament will pass into law. As the report clearly states “the fashion industry has marked its own homework for too long”.

Fashion Revolution welcomes the UK Environmental Audit Committee’s findings of their inquiry into the sustainability of the fashion industry. We too want to see a thriving fashion industry in the UK that employs people, inspires creativity and contributes to sustainable livelihoods in the UK and around the world and we believe that brands and retailers have an obligation to address the fundamental business model. We believe that the fashion industry in the United Kingdom and globally needs far reaching systemic change in order to tackle poverty, inequality and environmental degradation and greater transparency is the first crucial step towards solving its human rights and environmental crises.

“Fashion Revolution was a key contributor to this report, giving evidence to the EAC to help guide their understandings of the scope of the fashion industry and suggest policy decisions that would bring about wide scale change. Through Fashion Revolution tools like the Fashion Transparency Index, our manifesto, and our resources on microfibres, modern slavery and garment repair, we are excited to see the EAC follow through with some of our most critical demands. We hope to see the policymakers and citizens across the UK work hard to make sure that these recommendations are adopted into policy” said Policy Director Sarah Ditty.

The committee makes a number of recommendations in its final report.

We recommend that the Government strengthen the Modern Slavery Act to require large companies to ensure forced labour is not in their supply chains. Retailers including Foot Locker and Versace are failing to comply with the Modern Slavery Act. Company law must be updated to require modern slavery disclosures by 2022. Companies must report, or face a fine.

Fashion Revolution agrees that the Modern Slavery Act 2015, and specifically section 54, is an important piece of legislation for progressing greater transparency in the fashion industry (amongst other sectors) but its scope and implementation is too limited. Our recommendation would be to begin by strengthening the U.K. Modern Slavery Act transparency requirements through a variety of actions, including but not limited to:

- Extending the legislation to cover public procurement;

- Establishing, maintaining and monitoring an easily searchable public database of companies that are required to comply, including a copy of their annual MSA statements;

- Establish and require common, robust and comparable standards for reporting transparency information;

- Establish and enforce penalties for companies that do not comply.

We also want the U.K. Government to pass mandatory due diligence laws, building upon the recent regulatory examples in France and Switzerland.