JOIN OUR BOARD OF TRUSTEES

Fashion Revolution CIC is seeking new members to join our Board of Directors during a pivotal period of transition and strategic renewal. We are looking for leaders who share our values and are committed to supporting the long-term vision and sustainability of the organisation.

Recruitment is open to candidates globally, but due to regulatory compliance, we also seek candidates based in the UK specifically.

Please note that these are voluntary roles

About Fashion Revolution

We are the world’s largest fashion activism movement, mobilising citizens, brands, and policymakers through research, education, and advocacy. Our vision is a global fashion industry that conserves and restores the environment and values people over growth and profit.

About the Role – Treasurer

The Treasurer will support the effective governance and financial oversight of Fashion Revolution CIC. As we emerge from a period of organisational transition, the Treasurer will be a key figure in setting a strong foundation for our go-forward strategy.

This role involves guiding financial strategy, supporting oversight of systems and controls, and ensuring compliance with all relevant regulatory and funder requirements.

Key Responsibilities

Strategic

- Provide financial insight to support the charity’s strategic direction

- Ensure that financial planning supports the organisation’s goals

Financial Oversight

- Ensure timely and accurate financial reporting to the Board, including annual accounts and management reporting

- Oversee budget processes, financial controls, and policy development

- Lead on the appointment and engagement of auditors

- Work closely with the finance team to ensure sound day-to-day financial practices

Assets and Reserves

- Review and support investment and reserves policies

- Monitor the appropriate use and maintenance of the organisation’s assets

Governance

- Chair the Finance and Governance Sub-Committee

- Ensure the Board’s financial duties are understood and exercised properly

- Contribute to Board development, including annual review processes

General Trustee Responsibilities

- Actively contribute to strategic decision-making

- Ensure resources are used effectively and responsibly

- Uphold the values, reputation, and integrity of Fashion Revolution

- Participate in Board and subcommittee meetings, read relevant papers, and provide guidance using your expertise

Who We’re Looking For

We welcome expressions of interest from candidates with:

- Senior-level financial experience, ideally with Board or trustee exposure

- Knowledge of financial management in a charity, CIC, or not-for-profit context

- Familiarity with UK accounting and reporting requirements

- Strategic insight and a collaborative approach to governance

- A genuine commitment to our mission and values

About the Role – Board Member

This is a general Board Member role with a focus on strategic support and good governance. As we finalise our transition from a Community Interest Company (CIC) to a Charitable Incorporated Organisation (CIO), the new Board Member will contribute to building a stable, inclusive, and future-ready organisation.

We are particularly keen to hear from candidates who bring experience in at least one of the following areas:

- Strategic fundraising or philanthropic engagement

- Sustainable fashion or ethical supply chains

- Not-for-profit or mission-driven leadership

- Governance, particularly CIC to CIO transitions or membership-based models

Key Responsibilities

Strategic

- Contribute to shaping and overseeing the organisation’s strategic direction

- Offer constructive insight and support to the executive team and fellow Board members

Governance Oversight

- Help ensure the organisation meets its legal and fiduciary responsibilities

- Promote transparency, accountability, and inclusive decision-making

Engagement

- Represent Fashion Revolution’s mission, values, and objectives externally where appropriate

- Support Board development and help strengthen the organisation’s overall effectiveness

General Trustee Responsibilities

- Actively contribute to strategic decision-making

- Ensure resources are used effectively and responsibly

- Uphold the values, reputation, and integrity of Fashion Revolution

- Participate in Board and subcommittee meetings, read relevant papers, and provide guidance using your expertise

Time Commitment

We are currently completing a governance transition and laying the groundwork for a sustainable, forward-looking strategy. As such, the estimated time commitment is:

- At least five hours per week over the next six months (during the transition period)

- Thereafter, approximately 6–8 Board and subcommittee meetings per year, with periodic engagement with the executive team

Who We’re Looking For

We welcome expressions of interest from individuals with:

- Experience in at least one of the following:

- Strategic fundraising or philanthropic engagement

- Sustainable fashion or ethical supply chains

- Not-for-profit or mission-driven leadership

- Governance or legal structures (ideally including CIC to CIO transitions)

- A collaborative and strategic mindset

- A strong alignment with our mission and values

- Prior Board or trustee experience is helpful but not essential

Time Commitment

We are currently completing a governance transition and laying the groundwork for a sustainable, forward-looking strategy. As such, the estimated time commitment is:

- At least five hours per week over the next six months (during the transition period)

- Thereafter, approximately 6–8 Board and subcommittee meetings per year, with periodic engagement with the executive team

Please note that these are voluntary roles

Honorarium: £1,000 per year

How to apply

Please send your CV and a short covering note outlining your interest and relevant experience with the subject line ‘’Trustee’’ to recruitment@fashionrevolution.org. Applications will be reviewed on a rolling basis. The closing date for applications is July 31st, 2025.

Fashion Revolution is an equal opportunity employer. We are particularly interested in hearing from candidates from under-represented groups, including women, disabled people, Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic (BAME) communities.

Artículo redactado por Nora Sesmero Andrés, voluntaria de Fashion Revolution.

No estamos tan bien. La diversidad en la representación en la industria de la moda deja mucho que desear. Existen 1.000 millones de personas en el mundo con algún tipo de diversidad funcional que les limita a diario. “La primera vez que asistí a New York Fashion Week fue en 2017. Cuando llegué a la “ciudad que nunca duerme”, se volvió evidente para mí por qué la gente la llamaba así: simplemente no hay tiempo de dormirse cuando debes sortear todas las barreras de accesibilidad para personas con discapacidad”, confiesa Madison Lawson para Vogue México.

Judy Haumann, una activista de larga trayectoria por los derechos de las personas con discapacidad enfatiza: “La gente no nos ve como iguales en sus comunidades, en las escuelas, mezquitas, iglesias, sinagogas, clubes sociales, o lo que sea… Ellos nos ven y piensan ‘¿cómo podría vivir mi vida si fuese así?’”. Es por esta razón que la representación auténtica es algo vital.

En los últimos años, las redes sociales se han convertido en una herramienta con la que personas con discapacidad han podido controlar la forma en que estaban siendo representadas. Mientras se debate y se hacen llamados para una mayor diversidad, el floreciente movimiento body positivity abrió un espacio para celebrar la belleza en diferentes formas.

La modelo Bri Scalesse quedó parapléjica a los seis años tras un accidente de coche que le ocasionó lesiones en la médula espinal. Ella siempre ha demandado una representación de personas como ella, hoy puede representar a través de su trabajo y de las RRSS a todas esas personas que también lo demandan.

https://www.tiktok.com/@briscalesse/video/7171941421375737134?is_copy_url=1&is_from_webapp=v1

El modelo Aaron Phillip en 2018 se convirtió en el primer modelo, transgénero, y con discapacidad en ser representado por una importante agencia, después de que uno de sus tweets se hiciera viral. En un lugar similar está el modelo transgénero, con hipoacusia, Chella Man quien atrajo las miradas del mundo con las fotos que compartió en Internet. Gucci también acaparó los titulares al reclutar a Ellie Goldstein, una joven modelo con Síndrome de Down, que figuró como el rostro principal de su línea de belleza.

“Ya hora de que nos movamos más allá de la tokenización. Necesitamos ver a más personas frente a la cámara, pero también necesitamos verlas detrás. Necesitamos ver gente que se vea como nosotros en posiciones de poder, en todos esos lugares en los que hemos sido históricamente olvidados. Después de todo, ¿qué bien nos hace el ver a alguien que se parezca a nosotros en una campaña, si la marca no puede satisfacer nuestras necesidades? Lo mismo ocurre si seleccionan a una modelo para una sesión de fotos o para un desfile, pero esta no puede acceder a la locación del evento, ni al backstage”, afirma Madison Lawson.

Jillian Mercado le confesó a HOLA: “Resulta difícil lograr trabajar con un grupo de personas o estar en un lugar donde las personas aceptan y son abiertas y también pueden educarse a sí mismas sobre cómo pueden ser mejores y hacerlo mejor para asegurarse de que las diversas personas en su comunidad también pueden sentirse seguros y también pueden sentirse incluidos en esa conversación. Es tan importante poder decir que he podido”.

Sinéad Burke se dirige a las empresas y les advierte de que van a tener que empezar a abrir su lente a la accesibilidad porque el mercado está cambiando. Las empresas que hoy apuestan por el cambio están siendo las pioneras de una era que comienza a acercarse. Es el caso de Chamiah Dewey Fashion, la primera marca de Reino Unido que defiende la sostenibilidad y diseña moda para personas de estatura pequeña.

En otro artículo de Fashion Revolution escrito por Heloisa Rocha, Samanta Bullock exponía: “Hay que eliminar las barreras reales, físicas, digitales y, sobre todo, de actitud”.

“El otro día estaba hablando con una chica que me dijo que solicitó en una tienda de ropa la fila para personas discapacitadas y la dijeron que no tenían. Estaba muy enfadada, evidentemente. Tenemos que tener estas cosas en cuenta. Hay personas que no pueden estar en una fila mucho tiempo esperando”, comenta Marina Vergés, fundadora de Free Form Style.

La ropa también debe representar a las personas y para ello se deben conocer los conceptos de “moda adaptada” y “moda inclusiva”. Hay pequeñas diferencias entre estos dos conceptos: Moda inclusiva es la moda para todo tipo de personas, donde todos los cuerpos están representados, además de la raza, talla, edad o diversidad de género.

Y la moda adaptada, además de inclusiva, hace referencia a la ropa especialmente diseñada para personas con distintas movilidades. La moda adaptada facilita que las personas con movilidad reducida se vistan de forma independiente: cerrar una sudadera con cremallera con un solo brazo, o ponerse un pantalón fácilmente cuando estas en una silla de ruedas (te vistas en la cama o en la silla). La moda adaptada también puede ofrecer aberturas adicionales para que la gente pueda acceder fácilmente a partes de su cuerpo donde normalmente sería difícil de llegar con piezas estándar. La moda adaptada también puede ser ropa que se adapte a la sobreestimulación sensorial. Que tenga en cuenta la carta de colores para personas con poca visibilidad o coordinar un look con una visión daltónica.

En Free Form Style siempre han tenido claros estos dos términos y han diseñado sus colecciones entorno a ellos. Ellos quieren que sus clientes consigan tener autonomía. “Es importante la especialización en la moda. Los emprendedores no piensan en cubrir una necesidad en las personas cuando crean una marca de moda, piensan en cómo podrán obtener más beneficios. Pero eso ya no es posible. La idea es que la moda se adapte al cuerpo, no que el cuerpo se adapte a la moda. Se ha de normalizar la moda adaptada e inclusiva. Basta de pensar en marcas, debemos pensar en la comodidad, no en lo que es tendencia. Debemos incluir a personas discapacitadas en los equipos de trabajo y en el marketing, que se normalice realmente esta necesidad”, confiesa Marina.

https://vm.tiktok.com/ZMFu95Q7R/

Timpers es una marca de calzado de calidad, fabricadas en Alicante, cuya plantilla está formada por personas con discapacidad. Sus valores son la creatividad, derribar los estereotipos, el trabajo en equipo, probar a hacer las cosas siempre, defienden que nuestras capacidades importan más que nuestras discapacidades. “Actualmente, tres de cada cuatro personas con discapacidad, en edad laboral, no trabajan y todavía siguen existiendo desigualdades en temas tan importantes como pueden ser la igualdad de oportunidades, salarial o curricular. Nos hemos propuesto cambiar la vida de estas personas y demostrar que una normalización plena es posible, y demostrar que la discapacidad en los equipos de trabajo no es un inconveniente, sino un enriquecimiento para los mismos y que a las personas hay que valorarlas por sus capacidades y no por sus discapacidades”, afirma el CCO de Timpers, Diego Soliveres.

“Es simple: una prenda inclusiva es cuando todo el mundo se la puede poner, no solo una persona, sin necesidad de adaptarla”, explica Rut Turró para El País. Admite que se las ha visto y deseado para hacer pedagogía con este concepto de diseño universal. En este momento nace Movingmood, una asesoría para empresas textiles que quieran incorporar esta noción a sus procesos productivos. Uno de sus métodos consiste en analizar la accesibilidad de las colecciones y plasmarlo en un panel visual, un cánon que los diseñadores pueden seguir de ahí en adelante. Otra solución, esta para empresas de estampados y color, es el uso de cartas de colores para personas con daltonismo o hipersensibilidad. De 2011 a 2014, Rut Turró visitó 85 entidades e hizo más de 200 entrevistas a usuarios con diferentes diversidades, profesionales, cuidadores, terapeutas y familiares. Identificó nueve funcionalidades básicas de la ropa inclusiva:

- Usabilidad: Fácil de poner y quitar, vestir y desvestir.

- Autonomía.

- Facilidad de cierre.

- Atractivo: la moda y la funcionalidad van de la mano.

- Buen fitting para todo tipo de cuerpos.

- Que sea cómoda y evite las fricciones y presiones.

- Sensibilidad: evite irritaciones en la piel y aporte confort térmico.

- Que permita la libertad de movimientos.

- Que dé seguridad a la persona, que la haga sentir bien, que le suba la autoestima.

Las decisiones que toman las personas que trabajan dentro de las empresas importan mucho. Y más si se contemplan dentro de la industria de la moda, porque esta representa a muchas personas, influye en las decisiones de estas y da de comer a muchas otras. Una industria de la moda más igualitaria es una industria de la moda mejor.

Si quieres continuar leyendo y concienciándote acerca de la actualidad de la industria textil, pulsa aquí.

Artículo redactado por Nora Sesmero Andrés, voluntaria de Fashion Revolution.

Humana Fundación Pueblo para Pueblo es una organización sin ánimo de lucro que se encarga del reciclaje del textil en España. Los ciudadanos españoles nos desprendemos al año de 1’2 millones de toneladas de ropa, y eso tiene un gran impacto en el medioambiente.

Si por algo destaca Humana es por ser una organización transparente. En su web podemos encontrar toda la información trazada para que el ciudadano de a pie conozca cómo trabajan.

Esta fundación se dedica a reinsertar en el ciclo de vida las prendas de las que los consumidores nos desprendemos, aunque no dan abasto. De las 1’2 millones de toneladas de prendas que los ciudadanos españoles desechan al año, actualmente solo se recicla un 10%. Otros proyectos en España como Moda re- se dedican también a esta labor.

Humana tiene 5200 contenedores de donación de ropa repartidos por España, promoviendo que los consumidores donemos nuestra ropa cuando creamos que realmente ya no la podemos vestir, aprovechando todo su potencial. En sus plantas de reciclaje de Madrid y Barcelona, donde se puede acudir para conocer cómo trabajan, se observan pilas y pilas de sacas de ropa prensada. Algunas de esas sacas pesan alrededor de unos 400kg.

Cuando los ciudadanos dejan sus bolsas de ropa en los contenedores de Humana, estas se transportan a sus plantas de reciclaje y mediante un proceso rápido y efectivo se clasifican según su estado para dotarlas de un nuevo uso. Un 90% de estas son destinadas a la venta de segunda mano tanto en España como en los países donde realizan sus programas sociales.

De esta manera, tratan de fomentar la moda de segunda mano, a partir de la venta de ropa en sus tiendas, donde según muchos de sus clientes, podemos encontrar prendas completamente nuevas. Esto demuestra la mala educación que tiene el consumidor de moda a día de hoy. Por ello, creen que es importante educar a este en la sensibilización, que seamos conscientes del impacto que tienen nuestras compras. “Dado que las calidades de la moda rápida son pésimas, las prendas que se reciclan también son cada vez de peor calidad”, afirma el responsable de comunicación de Humana, Rubén González. La solución pasaría por dejar de consumir este tipo de moda y comenzar a invertir en prendas de calidad.

Parte de los beneficios que esta fundación produce se destinan a realizar proyectos sociales en países del sur, relacionados con la educación, la salud, la agricultura, el cambio climático, el desarrollo comunitario, etc. En países como China, Ecuador, Laos, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Senegal, Zambia y España. En 2020, sus proyectos de cooperación involucraron a cerca de 125.000 personas.

Algunos de los proyectos de educación se encargan de formar a profesores de primaria en el entorno rural, ya que defienden que los profesores bien formados, motivados y comprometidos son la mejor palanca para hacer avanzar la educación. Impulsan la agricultura urbana, ecológica y sostenible, además del desarrollo rural. En el ámbito de la salud, tratan de educar a las personas para prevenir el VIH. En 2021 se ha profundizado en el fortalecimiento de los programas relacionados con cambio climático y del trabajo junto a socios especializados. Esta labor contra las consecuencias del calentamiento global tuvo su prolongación en la COP26 de Glasgow, en la que Humana participó para compartir la experiencia acumulada mediante los programas Farmers Club, establecer lazos con otras entidades y detectar oportunidades para seguir promoviendo acciones en favor de la adaptación y la mitigación de las consecuencias del cambio climático.

Humana ha convertido un oficio antiguo, el de los traperos, en una manera de hacer que la moda sea circular y financiar con ello distintos proyectos sociales.

A partir de 2025, el reciclaje de ropa será obligatorio en la Unión Europea. Esto produce una sensación de esperanza, ya que será menos probable que encontremos imágenes como la del mercado de Kantamanto, en Ghana. Es importante poner el foco en lo que aún queda por mejorar, y la reducción de la producción y el consumo son claves para hacer que la industria de la moda de un salto hacia la sostenibilidad.

Otra de las tareas pendientes consiste en que las prendas que se produzcan sean de un solo material. Debido a que reciclar ropa de diferentes composiciones es un trabajo complejo y caro.

La organización trabaja en el fortalecimiento de iniciativas de I+D+i para prolongar el ciclo de vida del textil y el calzado y, al mismo tiempo, multiplicar sus posibilidades de reaprovechamiento, en el marco de la economía circular y la jerarquía de residuos. Por ello, más allá de la preparación para la reutilización, la Fundación colabora en España con diferentes asociados en el impulso de proyectos de diversa naturaleza, desarrollando de modo conjunto soluciones concretas en aras de impulsar una mayor circularidad en la gestión del textil usado. Como su participación como miembros impulsores del Pacte per a la Moda Circular de Cataluña o su reciente adhesión al Consejo Asesor del proyecto Life Kanna Green, nacido para proponer y definir un nuevo modelo de consumo y economía circular para el calzado, basado en los principios del ‘Cradle to cradle’, donde nada es un residuo.

Otros de los objetivos de Humana son: conseguir abarcar más cantidad de ropa para poder reciclarla, optimizar sus procesos de reciclaje, ampliar el número de tiendas, generar empleo, avanzar con sus proyectos sociales, trabajar con otras empresas del sector de la reutilización, ayuntamientos, etc. Su mensaje es positivo, creen que vamos hacia una moda sostenible, mucho más regulada e inteligente.

Si quieres leer el anterior artículo de la autora, pulsa aquí.

In this guest blog post by Anvita Srivastava, revisit Rana Plaza to discover why the call for an extension to the Bangladesh Accord on Fire and Building Safety is so urgent.

No one should die for fashion, and that’s why this legally binding agreement between apparel brands and global trade unions help ensure that disasters like Rana Plaza never happen again. Unfortunately, this game-changing agreement expires on 31st May 2021. If the Accord is not renewed, the safety of over 2 million workers in 1,600 garment factories will be left in the hands of voluntary, non-enforceable Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) initiatives, which have been unable to prevent mass casualties.

Brands must stop dragging their feet and sign on to the renewed Bangladesh Accord now, and help extend the internationally binding agreement to other countries where garment workers still face unsafe working conditions. We shouldn’t have to wait for another Rana Plaza for change to happen.

Before the Accord: Rana Plaza

On 23rd April 2013, a TV channel recorded footage that showed noticeable deep cracks in the eight-storey Rana Plaza building. The top five floors of the building were occupied by five garment factories. The shops and banks on the lower floor were closed and people immediately evacuated. By the end of the day, the building was deemed safe by the building owners and workers were asked to return the next day.

At around 9 am on 24th April, with over 3,000 factory workers inside, the Rana Plaza building collapsed completely burying thousands of workers under it. The local people nearby described the collapse as a massive earthquake. Immediately the onlookers and neighbours rushed towards the site, to see body parts buried under a twisted mass of metals, concrete, and machinery and hear the cries for help.

As the enormity of the tragedy quickly became apparent, locals and rescuers tried to evacuate as many people as possible. Haunting photographs of family members desperately looking for their loved ones through the debris circulated online. Relatives were seen with handkerchiefs trying to block out the rancid smell as they tried to identify their family members through rows of dead bodies. In the days following the incident, rescuers were still trying to dig with drills, shovels and bare hands to retrieve the bodies buried under the wreckage. The final evacuation ended almost after a month in May, with the incident drawing global attention and public anger.

The factory workers had pleaded to not be sent inside that morning. The supervisors chose to ignore the warning signs and threatened them with a month’s salary cut if they did not comply. Later the world witnessed the aftermath of a completely avoidable disaster in disbelief.

Why did the workers still enter the factory?

In the days and weeks leading up to the collapse, workers were anxious about cracks in the building and had even previously been evacuated the day before due to safety concerns. The supervisors and managers cajoled them to work that day. But why?

The answer lies in the massive income disparity between the workers and the brands they produce for. To give you an idea at the time of the incident workers earned between 35 USD and 60 USD per month for a pair of jeans that cost less than 5 USD to produce and would sell for more than 80 USD globally. Their vulnerability and struggle for survival make them the disposable assets of the supply chain. In addition to that, the majority of the garment workers are young women, often victims of gender-based violence. Many of them financially support their families and fear of losing jobs is greater than the risk to their lives.

“Our tasks kept piling up. The bosses said they wouldn’t let us leave until we had finished the task, and said we wouldn’t get the day’s salary plus the two hours of overtime if we left without finishing the order. We get a pretty small salary. We can’t risk losing even a tiny part of it.” – Roksana

“Darkness engulfed the entire place with thick clouds of debris. I heard screams around me. My heart started pounding…I lay down near a pillar, thinking that perhaps I was going to die. We were being roasted inside.” – Mahmudul Hasan (source)

As distressing as these testimonies are, the incident itself was depressingly predictable. Bangladesh is the second-largest exporter of garments in the world and employs roughly 4.4 million people, mostly women, contributing more than 11% to the country’s GDP. Unsurprisingly, the Rana Plaza was far from the first or even the last incident of its kind in the notoriously unsafe Bangladesh garment industry. It is, however, considered the worst disaster in the garment industry as the factories were producing clothes for many major brands, who after several audits had failed to detect the safety violations that would ultimately lead to the tragedy.

The investigation revealed that the factory was built without proper permission on unstable land, over a filled-in pond. The owner had also built the last three stories illegally using sub-par construction materials thus compromising its structural integrity. The building was inefficiently inspected and poorly managed. The factory supervisors main concern was to meet the order deadlines and workers safety was not their priority. The brands insisted they had conducted the audits as per regulatory requirements. Then how is it possible that none of the audits could detect the violations? Some of the reasons provided were that the audit scope only covered the basic supplier criteria and did not include assessing the building’s structural integrity.

The aftermath of Rana Plaza

Public outcry over the collapse and regulatory issues forced the largely Western apparel companies to take action and ensure the safety of workers in their supply chain. Over 200 brands and retailers joined forces to collaboratively develop two historic parallel agreements called the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh and the Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety. The Accord is the first modern legally binding agreement between global brands and retailers and trade unions that represent garment workers. It is governed by a Steering Committee with equal representation of apparel companies and trade unions with a neutral chair provided by the International Labor Organistion (ILO).

It is a crucial breakthrough for workers’ rights as it holds the brands, retailers and factories accountable through arbitrations on failure to fulfil the obligations. It aims to ensure building safety by establishing a legitimate system to conduct factory inspections and take corrective actions. It has also enhanced supply chain transparency by listing all the signatories, supplier factories in the public domain and publishing inspection outcomes, measures and factory performance over time. Lastly, it has been instrumental in giving a voice to the workers by including worker unions in their governance structure and actively involving them in the decision-making process.

Impact of the Accord

Since its inception, the Bangladesh Accord has brought about a much-needed change in the Bangladesh garment industry and led to tremendous progress in factory working conditions. The numbers speak for themselves. More than 145,000 safety violations have been detected at covered factories under the Accord since 2013, of which 93% of safety issues identified during initial inspections are now remedied. Over 1,300 joint labour-management factory level Safety Committees have been set up to monitor safety measurements regularly. The Accord’s grievance mechanism has also proved effective in resolving over 700 safety complaints from factory workers and their representatives.

Unfortunately, the Accord expires in May 2021. Frequent and almost regular reports of fire and safety accidents in Bangladesh garments factories have made it more than evident that the Accord’s work cannot be handed over to the ill-equipped national agencies. The last reported incident in Bangladesh took place on 8th March 2021 at a textile chemical factory, taking the life of one and injuring 20 others.

With the Accord soon coming to an end, the workers will be left at the mercy of voluntary programmes without its legal enforcement. Its effectiveness can largely be attributed to the inclusion of unions as signatories who can keep the member brands and retailers accountable. Covid pandemic has exacerbated the workers’ financial woes and there is still an immense amount of work to be done. But the Accord’s expiration runs the risk of it turning into another industry-led voluntary tool.

According to Clean Clothes Campaign, the Bangladesh Accord has brought great progress to the safety situation for over 2 million garment workers in Bangladesh, but this progress must be protected:

“The Bangladesh Accord is so successful because it is a binding agreement that has real punishments for brands, retailers, and factories that do not take enough action. Unions take up half of the seats in the Accord’s governance structures and can hold brands accountable. An international binding agreement will have to be signed to keep the Accord’s most effective elements in place, and can also be used to ensure that eventually other countries will be covered by a similar programme.”

As consumers, we can do our part by sharing support for the Accord’s extension and calling upon brands to take action to #ProtectProgress.

We can do this by first informing ourselves of the challenges faced by garment workers and the mechanisms in place to ensure their safety. Greater awareness among consumers can make our voices loud enough to be heard by powerful brands and retailers. After all every time we wear a clothing item with the tag “Made in Bangladesh”, we owe its very existence to an unknown and unrecognised factory worker toiling for the rich brands. The least we can do is share our privilege and platform to demand a humane, safe and dignified workplace for those whose cries for justice have been deliberately silenced and unheard for too long.

For more information about the Bangladesh Accord, watch this video from Clean Clothes Campaign:

Sources:

https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424127887323789704578444280661545310

https://www.reutersevents.com/sustainability/supply-chains/rana-plaza-rebuilding-more-factory

https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/05/11/bangladesh-accord-new-phase-should-protect-unions

https://cleanclothes.org/campaigns/protect-progress

https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/opensecurity/reason-and-responsibility-rana-plaza-collapse/

https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/AAAJ-07-2015-2141/full/html

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3265826

https://www.workersrights.org/our-work/bangladesh-accord/

Exactly one year ago, a massive fire at Nandan Denim factory in Ahmedabad, India claimed the lives of seven factory workers, once again highlighting the miserable, and often inhumane, working conditions in many garment factories.

Ahmedabad is a fast-growing city in the western state of Gujarat, India. The city’s outskirts have been exponentially growing as a garment manufacturing hub for various multinational brands across the globe. The Day of 8 February 2020 started like any other day for the garment workers at the Nandan Denim factory. No one could have predicted the horror that would unfold later that evening. A massive fire started in the shirting department of the factory and blazed through the two-story factory in the evening. At the time, more than 60 workers were present on the floor with only a single entry and exit door. The lone door could only be reached by climbing a steep ladder, making the escape incredibly difficult. The fire quickly engulfed the factory as it was full of highly flammable denim, fabric and textile dust. As smoke billowed through the windows, the workers’ cries for help could be heard while they struggled to get out. It took almost 22 hours to douse the fire with the tragedy ultimately killing seven workers, ranging in age from 22 to 47.

Grieving families of the victims had to wait for a week to identify the evacuated bodies which were charred beyond recognition. A devastated man who lost his nephew in the blaze said “We can’t even mourn our dead because we don’t know which one is ours,” After the fire, police investigation revealed that the factory had violated multiple safety regulations. A simple visual inspection showed absence of ventilation and safety measures such as fire escapes or even basic emergency apparatus. The single entry and exit door, only accessible through a ladder, further sealed the fate of the workers.

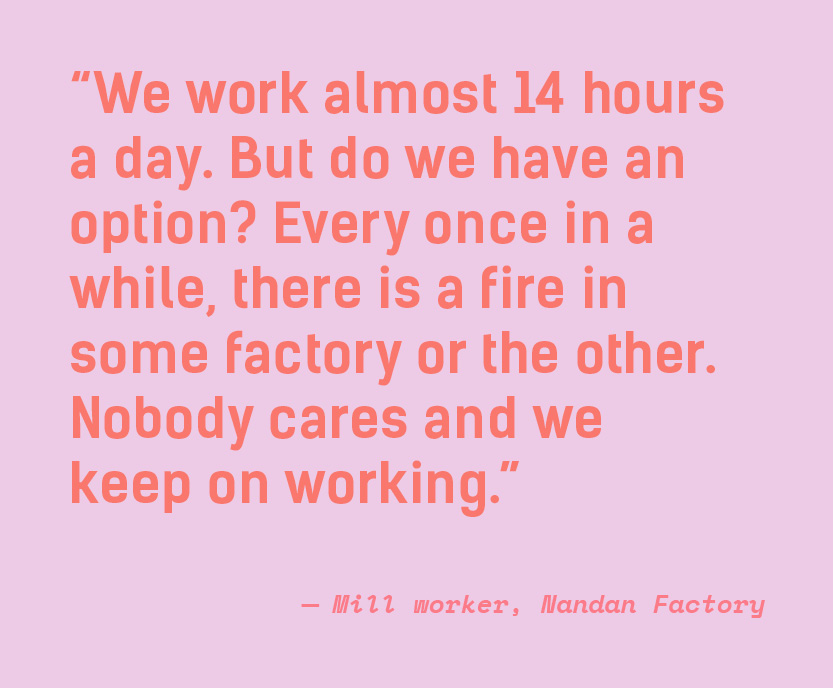

Nandan Denim claims to be India’s largest and world’s fourth-largest denim fabric maker, manufacturing denim fabric, shirting fabric and yarn for some of the biggest brands in the world. Its factory workers, mainly women, earn about 35 cents per hour, often working for 14-hours per day in unsafe conditions. Survivors told reporters that to meet the unrealistic client demand they are forced to stitch more than 400 garment pieces a day, often skipping meal and toilet breaks. One worker said “We work almost 14 hours a day. But do we have an option? Every once in a while, there is a fire in some factory or the other. Nobody cares and we keep on working.” In fact, workers continued to work even after the fire had started as there was no adequate alarm system to start the evacuation process. How the mandatory audits failed to detect such large scale violation of minimum safety requirements can be attributed to a corrupt system which exploits the most deprived and poverty-stricken faction of our society. The workers are often migrant labourers, sub-contracted to small contractors. They live and work in unimaginably miserable conditions because for most of them this is the only means of survival. They rarely have any voice or identity and are immediately dismissed upon expressing any grievance.

In light of these revelations, perhaps I should retract my previous statement. Given the clear human exploitation, gross negligence of regulations and complete disregard for human life, all fueled by the fashion industry’s insatiable demand for speed and cheapness, maybe such incidents should have been predicted and even expected.

The fact is this wasn’t the first or the last fatal fire incident in garment factories, let alone Nandan Denim factory. After the February fire, the factory was closed by local safety and health authorities and its licenses were suspended. Nandan Denim agreed to pay $14,000 to the next of kin of the victims and also provide a job to one of their family members. Merely six months later, another major fire was reported at a production unit in the premises of Nandan Denim. Fortunately, this time there were no fatalities. This is the continuation of the same toxic cycle – the media limelight eventually recede, the “situation” is handled, the activists mollified and virtually no credible action taken beyond the public relations exercise and paying off the legal fines – until something similar happens again.

Interestingly, although Nandan Denim claims to be the supplier to major international retailers on its website, most of the brands distanced themselves after the incident and declared to have no relationship with them – which brings us to the crux of the issue. The lack of accountability from the brands for whom these garments are ultimately being manufactured. This can be attributed to the multi-tiered and complicated nature of garment supply chains because of which it is a near impossible task to trace a specific item to one factory. Typically, the factory that sews the garments and ships them for distribution is the tier closest to clothing brands. Below these are fabric manufacturers such as Nandan Denim. As we move further down the supply chain, fabric suppliers, such as spinning mills, are some of the least transparent. This makes it easy and convenient for brands to shrug off the responsibility of these incidents.

To bring about long-lasting and meaningful change, brands must acknowledge and take ownership of their entire supply chain. They hold the most power and cannot abdicate responsibility for malpractice at any level of the value chain. After all, every single worker toiling at different tiers contributes to the creation of the garment they sell and profit off millions of dollars under their name.

Sadly, it is evident from past incidents that brands are highly unlikely to act of their own accord unless their reputations are at stake. For instance, it was only after the Rana Plaza tragedy in 2013, that apparel companies signed the legally binding agreement on health and building code inspection called the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh. The results were gradual but labour advocates say it has brought about a physical transformation in Bangladesh factories. However, the change has not been seen throughout the garment industry and the code of conduct focuses only on implementing measures which can be seen and audited.

Work rights advocates, JJ Rosenbaum, of the Global Labor Justice Project said “Sometimes the problem we face is a compassion fatigue: the notion that it can’t be that bad if it’s happening all the time,” The Nandan factory incident is just one of the many examples of egregious violations in safety standards leading to loss of human lives in garment factories. Fire accidents have become such a regular and repeated phenomenon in the garment supply chain that they are simply accepted as part and parcel of the business. Fires caused by faulty electronics, boiler explosions or illegal conversion of buildings ill-equipped for industrial use are a common occurrence in garment factories globally. These lone incidents can be forgotten but lives lost cannot be replaced.

Work rights advocates, JJ Rosenbaum, of the Global Labor Justice Project said “Sometimes the problem we face is a compassion fatigue: the notion that it can’t be that bad if it’s happening all the time,” The Nandan factory incident is just one of the many examples of egregious violations in safety standards leading to loss of human lives in garment factories. Fire accidents have become such a regular and repeated phenomenon in the garment supply chain that they are simply accepted as part and parcel of the business. Fires caused by faulty electronics, boiler explosions or illegal conversion of buildings ill-equipped for industrial use are a common occurrence in garment factories globally. These lone incidents can be forgotten but lives lost cannot be replaced.

As consumers, we can hold global brands accountable to create greater transparency of the regulatory mechanisms and adherence to international and local human rights and safety laws. In Fashion Revolution’s latest Consumer Survey, 74% of people agreed that fashion brands should publish which factories they use to manufacture their clothes and 73% said they should publish their fabric suppliers. Now we need demand that industry put this sentiment into action. First, we must call on these brands to disclose their suppliers at every level of the value chain, from sewing and garment making facilities to raw materials suppliers. Then, we must demand that brands create policies and purchasing practices which enable all of their suppliers to ensure every worker is safe from harm. The guidelines and codes of conduct, such as the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh, should not exclusively focus on physical infrastructure. They need to rectify issues that affect the long-term well-being of workers such as long working hours, physical and bodily exhaustion, intense work rhythms, harassment, and the lack of any meaningful representation. They have to coordinate and work with labour unions to actively monitor and resolve issues that go beyond refurbishing buildings and fulfilling the audit criteria and ensure basic human rights for workers.

Ultimately, we need a collective shift in mindset which recognises workers as human beings deserving of leading a life with dignity, safety and security – basic rights that most of us are privileged with and take for granted. No human should have to risk their health and safety to earn an honest living. Essentially the workers are paying the price with their health and all too often their lives, only to save brands a few cents on a pair of jeans. As we mark the anniversary of this tragedy, we must ask ourselves, after all the societal progress and development of the 20th century, have we degraded human life to be worthy of just a few cents?

December 10th marks the celebration of Human Rights Day around the globe – a moment to recognise the impact of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights on livelihoods and to affirm the importance of human rights everywhere. In the fashion industry, and during a moment when the global pandemic has upended business-as-usual, it’s more important than ever to fight for the rights of the people working in garment supply chains and demand an end to forced labour.

Severe labour exploitation takes place in fashion supply chains in many forms, from home-based workers lacking social protection to the prevalence of child labour on cotton farms. According to the 2018 Global Slavery Index, garments are the second highest at-risk product category for modern slavery imported into G20 countries1. Even where working conditions don’t meet the standard of forced and bonded labour, the vast majority of workers across the fashion supply chain live in poverty, earn far below a living wage, and lack any ability to unionise in order to negotiate their wages or for better working conditions.

Paul Roeland, Transparency Lead at Clean Clothes Campaign, explains: “The current pandemic has shown a terrible light on how unfair the fashion supply chain is. Garment workers need immediate relief – but it also shows that we cannot simply go back to the situation as before. There should be no going back to normal, as the “normal” was deeply flawed. We should use the coming recovery to build fundamentally different, fairer, and more sustainable models for fashion. Both people and planet simply cannot go back to where they were.”

How can legislation improve conditions for the people who make our clothes?

Clean Clothes Campaign and Fashion Revolution have worked alongside more that 65 organisations in publishing the Civil Society European Shadow Strategy for Sustainable Textiles, Garments, Leather and Footwear (TGLF). A shadow strategy is an unofficial policy strategy presented to government officials as recommendations for formal legislation. The shadow strategy calls upon the European Commission, Members of the European Parliament and EU Governments to build and promote a fashion industry that respects human rights, creates decent jobs and adheres to high social and environmental standards throughout the value chain.

When it comes to improving the human rights of garment supply chain workers, the shadow strategy proposes Human Rights Due Diligence Legislation as one of the key recommendations. Fashion Revolution’s Global Policy Director, Sarah Ditty, says: “We expect to see this legislation proposed by the European Commission in 2021, and in the meantime, we will be pushing to ensure that this legislation includes robust and effective access to justice and grievance mechanisms for people working in exploitative and dangerous conditions while making products for big brands.”

This shadow strategy isn’t the only government initiative pushing for human rights in globalised supply chains. Modern Slavery Acts in the UK and Australia and the California Transparency in Supply Chains Act came into force over the last decade in order to address working conditions in global supply chains. Yet, what is lacking is effective implementation and liability for companies that don’t comply. For example, when companies fail to comply with the UK Modern Slavery Act, they receive nothing more than a strongly worded letter. “Governments have let a system and culture of unfair trading practices go unchecked,” says Sarah Ditty. “This has played a huge role in forcing garment workers to remain stuck in poverty-level pay, exploitative, precarious and dangerous working conditions in countries like Bangladesh, Cambodia and even Eastern Europe. The civil society shadow European Strategy for Sustainable Textiles, Garments, Leather and Footwear calls upon the European Commission to put in place measures to end abusive purchasing practices, such as late payments for orders or short-notice order cancellations, which can directly result in human rights violations.”

How do trade regulations impact workers on the ground?

The clothes we buy in store (or online, more recently) are unlikely to have been made in the country where it was purchased. In fact, the average cotton t-shirt is likely to have passed through many countries and many pairs of hands on its journey from raw material into finished product. This globalised value chain means that international trade regulations have a profound impact on workers. The European Union’s system of trade preferences, known as GSP, are meant to ensure respect for civil liberties, freedom of association and other labour standards, set out by the International Labor Organisation, as a necessary condition for countries to import their goods to the EU.

But when goods are made inside of the EU, governments have even more control over working conditions. Paul Roeland says: “The EU should make sure that all Member States set minimum wages that, at minimum, take living costs into account, and should be on a roadmap towards a real living wage. Currently the minimum wages in many Member States are very far away from that. Beyond that, the EU should strengthen the Non-Financial Reporting standards, and provide open and easy access to these reports. This will in turn allow responsible investors to base their decisions on credible, data-based evidence of performance and progress.”

He adds: “Governments and public institutions are also major consumers of garments; think about uniforms for anybody from bus drivers to nurses, work clothing, etc. They should set an example by invoking strong social and environmental criteria as part of their public procurement.”

How can individual citizens support legislation that protects garment workers?

How can individual citizens support legislation that protects garment workers?

Contact your Member of European Parliament, (you can look yours up here), and let them know that you support and want to see them adopt the recommendations put forward in the civil society shadow European strategy for sustainable textiles, garments, leather and footwear. Tell your MEP (via email, phone call, tweet, or DM) that you want them to do more to improve the working conditions, wages and respect for human rights of the people across the world that make the clothes you wear, both inside and outside the EU.

2020 has been a year for the history books. Some of us have fared better than others, but it’s safe to say that everyone has been affected by the global pandemic in one way or another. Here at Ethical Made Easy, we’re incredibly privileged to be living in Australia, as is everyone living in our country of origin, New Zealand. COVID-19 is on the verge of being eradicated in both countries thanks to fast-acting governments, strict lockdown measures, and domestic border closures. But that hasn’t come without the emotional toll on individuals and the monetary toll on small businesses in particular.

Of course there are some businesses that have been able to pivot and succeed in this pandemic (we’re looking at you, alcohol delivery services). But for small businesses, this has been the exception, not the rule. Even in our ‘lucky countries’ the pandemic has wreaked havoc on the little guys. A report by Quickbooks and YouGov found that 63% of small businesses were negatively impacted by COVID-19, 37% said remaining viable was a major concern and 21% were concerned about ensuring their staff had work. Remember, these findings are from Australia where things have almost returned to ‘normal’.

As an ethical brand directory, Ethical Made Easy is home to a multitude of amazing small businesses who are actively working towards creating a better future for the fashion industry and beyond. Unfortunately the founders of these brands are no strangers to the negative effects of COVID-19, particularly the way it’s impacted their workers. Kopal is the founder of her eponymous brand that’s usually based in the coastal paradise of Byron Bay, Australia. She found herself in India for eight months where she witnessed firsthand hundreds of millions of migrant workers fleeing from larger capital cities to their rural homes, many of whom worked in the fashion and textile industry and ran out of work due to cancelled orders from large fashion brands in the western world. Kopal described it as a “humanitarian crisis of epic proportions.” But instead of refusing to #PAYUP like many large businesses have during COVID-19 (as we’ve seen through Remake Our World‘s campaign), Kopal continued to support her workers in any way she could—whether that was paying them full wages or recharging their mobile phone accounts. This commitment to doing better is the backbone of every small business we work with and it’s why they deserve our support more than ever right now.

Unfortunately other small labels that are part of the Ethical Made Easy community haven’t been able to continue, even though their founders have fought incredibly hard to stay afloat. Some have been forced to pause production or even shut up shop indefinitely after several months of uncertainty. With small businesses already competing against fast fashion giants, it’s no wonder the pressure has become too much and the desire to support their makers is negated by dwindling sales and tight budgets (or lack thereof).

The saddest part is, these small labels are the ones who’ve considered fair wages, an ethical supply chain and sustainable production from day one. When you support a small business you’re actively supporting the communities they employ and are keeping the dreams of these founders alive. Not to mention, by shopping small you’re diverting funds away from big brands and shareholders, and into the hands of those trying to make a change in the world. It’s these reasons (amongst many) that prove why we should be supporting small businesses committed to a better future rather than the big players that are only concerned about the bottom line.

If you don’t believe your dollars can truly make an impact, here’s an example of what supporting a small business can do. Australian brand Thankyou is a social enterprise that sells personal care goods and diverts all profits to a charitable trust focused on tackling poverty. It comes as no surprise that people wanted to buy personal care products—specifically hand sanitiser and hand wash—during a global pandemic. Aussies made the wonderful decision to support Thankyou during this time—whether that’s because hand sanitiser was a hot commodity or because they wanted to buy from a charitable business is anyone’s guess. Either way, it led to huge profits for Thankyou and the subsequent donation of those profits to deserving charities. The dollar figure on those profits? $10 million to be exact!

Co-founder of Thankyou, Daniel Flynn, touched on these profits in the brand’s recent campaign video, “While the world’s been in turmoil, some people got filthy rich…We know because we’re one of them.” This led to a realisation for Flynn and the Thankyou team—if they partnered with corporations larger than themselves, in the same way that Kanye West partners with Adidas for example, Thankyou could make monumental profits that could literally change the world. “That wouldn’t have been $10 million we made in a few months. It would have been literally hundreds of millions of our collective consumer dollars,” Flynn said. This is why Thankyou has put a callout to two of the world’s largest brands, Unilever and P&G, to continue Thankyou’s trajectory at a much larger scale. You can track the brand’s ‘moonshot’ plan here.

We’ve always known that small businesses have the power to make huge change in the world, but seeing it in practice at a time when it’s more necessary than ever before has motivated us to continuously do better and demand better.

This awe-inspiring example proves that everyday consumers, like you and I, are pivotal in making campaigns like Thankyou’s succeed. By buying from small businesses, we can actively make changes in communities all around the world. Imagine if we showed the support to a brand like Kopal (or any of the brands from our directory) in the same way that we’ve been able to support Thankyou. Kopal could potentially employ makers in India who’ve lost their jobs due to large brands refusing to #PAYUP. Not to mention, the products made by these small businesses are made far more sustainably and ethically for both the maker and the consumer. So the impact goes much further than helping those in need; it has the potential to benefit the health of our planet and its people well into the future.

When the time does come to make your next purchase, we encourage you to pause and consider who you’re buying it from. Ask yourself if the purchase is going to support a small business that literally exists to make the world a better place, or will your hard earned dollars be stuffing the very large pockets of billionaires who are only concerned about profit and nothing else? Will your purchase be supporting minority business owners, who experience less access to capital than those more privileged? The power is in your hands—isn’t that exciting?

We live by the adage, do the best you can, where you are, with the resources you have. If you have the means to shop ethically, amazing. But don’t stop there! Sign the Fashion Revolution Manifesto and the #PAYUP petition, listen to informative podcasts like Remember Who Made Them, watch films that encourage grassroots change like 2040, and continue your education by following Ethical Made Easy —we’re always open to new ideas, suggestions and life-affirming chats, so don’t be afraid to say hi.

Follow the work of Ethical Made Easy on Facebook and Instagram.

Nasreen Sheikh, child labour and forced marriage survivor, social entrepreneur and gender equality advocate, shares her journey from exploitation to empowerment with Fashion Revolution.

My work as a young female social entrepreneur was first documented publicly by Forbes in 2012, but I’ve been actively organising women to work and protect each other since I escaped child slave labour in the garment industry in Kathmandu when I was about 12 years old. Due to my birth being undocumented, like most births where I was born, I’m not sure how old I am. My guess is 27 to 29 years old. From the moment of birth, the society of the rural village I come from teaches female children that their existence is insignificant. If one’s own birth does not matter, then the conditions in which she lives, works, strives, suffers, and dies also do not matter. At an early age I came to believe that girls are simply commodities that are bought and traded as such. We are not human beings.

Growing up, I witnessed unconscionable atrocities against children and women, including some of my own female family members being murdered for speaking up for themselves. By age 9 or 10, my life seemed destined for the same oppressive path. So, I escaped my village for the capital city of Kathmandu, where I worked 12-15 hours per day in a textile sweatshop as a child labourer, receiving less than $2 per gruelling shift — only if I completed the hundreds of garments demanded of me. I ate, slept, and toiled in a sweatshop workstation the size of a prison cell, often picking sewing threads out of my food and being too afraid to look out the window. I was surrounded by pieces of clothing day and night. I HATED those clothes. They were woven with the energy of my suffering. At the end of each day, I would collapse onto the large bundles of clothes and daydream about where they would end up and who would wear them. Some of you may be wearing those clothes right now.

As a young village girl, I would look at the stars and think about the connection of all things throughout the universe. Had I not become a lifetime advocate for ending slavery, I would’ve loved to become an astronomer. I’m fascinated by stars. I’ve come to love a quote of Carl Sagan’s: “The cosmos is within us. We are made of starstuff. We are a way for the universe to know itself.” I believe everyone on this planet and all life is in a reciprocal relationship, where each individual action affects the whole. This understanding has been deeply integral to the holistic approach I’ve created to incorporate all 17 sustainable development goals into my work.

I’m currently accomplishing these goals by building women’s empowerment training centres through my non-profit organisation, Empowerment Collective, and my social fashion business, Local Women’s Handicrafts. I organised hunger relief efforts during the 2015 Nepal earthquake, helping thousands of women feed their families, and more recently, we served over 360,000 meals to rural villages affected by COVID 19. In an effort to support women’s hygiene, we’ve distributed over 7,500 menstruation hygiene kits since 2014. Additionally, we brought the first water sanitization system to a rural village in Nepal, where 71% of its water sources were toxically polluted.

Our online store is bringing ethical and fair-trade goods to the world and we’re sharing the stories of the women who produce our sustainable fashion products. Our empowerment centres use affordable, clean, and sustainable energy by utilising both solar power and bio-gas units. We’ve shown innovation in the fashion industry by using recycled materials and non-electric looms to create our products, while preserving generations-old handicraft traditions. We’ve reduced income inequality by training women in a country where currently only 0.01% of business owners are women. In an effort to promote a more sustainable city, we’ve distributed thousands of reusable shopping bags in Kathmandu, one the most polluted cities in Asia. We’ve also been advocating for responsible consumption through our million-mask initiative that’s been teaching people to use sustainable, reusable masks during the COVID-19 epidemic. Our use of natural dyes in our production process takes into account the effect we have on life below water, and the textile developments we’ve created in collaboration with local hemp farmers support life on land as well as local animal habitat preservation.

Since 2008, we’ve offered quality education through 1,950 skills training program workshops, educating over 5,000 women with real-world working skills. After becoming the first girl in my village to ever escape forced marriage, I’ve been an outspoken proponent of gender equality. We also provide women with decent work and economic growth by following the 10 principles of fair trade. We honour the concept of peace, justice, and strong institutions by creating safe space centres for women to work in areas where they are most at risk. In order to reach our goals, we’ve partnered with many different organisations, including Fashion Revolution, LA Summit, Activists and several universities.

Follow @_NasreenSheikh and @Empowerment_Collective to keep up with Nasreen’s work.

Today, Fashion Revolution is supporting the Tamil Nadu Alliance in the launch of the Tamil Nadu Declaration and Framework of Action, which calls upon major fashion brands and retailers to do more to tackle exploitative working conditions within textile spinning mills in the region and expand transparency to cover all textiles production sites in their supply chains.

The Tamil Nadu Alliance is a coalition of civil society networks, representing over 100 grassroots organisations, working to improve the conditions of workers in the textile supply chain in Tamil Nadu. The global fashion industry is a vital source of jobs across southern India, employing approximately 280,000 workers, particularly young women.

Excessive and involuntary overtime, extremely low wages, physical and sexual violence and restriction of freedom of movement – many of which are indicators of forced labour – have been documented by civil society groups for many years. This is why more urgent and collaborative action is needed to improve the situation for workers in the industry.

The declaration calls upon major fashion brands and retailers to help eradicate severe labour exploitation in textile spinning mills in southern India through reform on 5 key areas:

- Transparency: Expand supply chain transparency beyond tier 1 cut-and-sew operations by publicly disclosing the details of all textile, raw material manufacturing processes, and finished product facilities in the global supply chain.

- Policy development and engagement: In Tamil Nadu, proactively support policy implementation efforts on minimum wages for textile workers, internal complaints committees, hostel registration, statutory employer benefits, registration of migrant workers and labour inspection.

- Fair and equitable purchasing practices: Adopt responsible sourcing and purchasing practices on price and order placement, and take steps to consolidate the supply chain by creating stable, long-term relationships with tier 2 and 3 suppliers.

- Worker-centred monitoring mechanisms: Instead of relying on third-party social audits, develop collaborative worker-centred, transparent and accountable mechanisms to monitor compliance with labour rights standards.

- Grievance mechanisms: Support civil society efforts to develop a collaborative grievance mechanism that provides effective remedy for mill workers in Tamil Nadu.

In support of the Declaration, Fashion Revolution has authored a new report, ‘Out of Sight: A Call for Transparency from Field to Fabric’, which explores why greater transparency beyond the first tier of the supply chain is necessary and reviews the current supply chain transparency efforts of 62 major brands and retailers that have links to textile manufacturers in the region.

In support of the Declaration, Fashion Revolution has authored a new report, ‘Out of Sight: A Call for Transparency from Field to Fabric’, which explores why greater transparency beyond the first tier of the supply chain is necessary and reviews the current supply chain transparency efforts of 62 major brands and retailers that have links to textile manufacturers in the region.

As part of this collaboration, we will be periodically monitoring and publicly reporting on brands’ efforts towards the first goal of supply chain transparency beyond the first tier.

Click here to read the report and learn more.

With large proportions of the world taking part in a global lockdown, we are being made to adapt to a new normal. For many of us this means working from home, a life lived in lounge wear and only leaving the house when absolutely necessary.

The impact of this ‘new normal’ on the supply chain that provides our lounge wear is, however, something completely different. You may have seen some news coverage of this drastic shift, but it will likely have focused on the formal employment sector for textile workers, overlooking the vast numbers of workers who have little to no contract at all, the informal sector.

In this article, I will illustrate the impact of this virus, starting from the end of December when the outbreak was first announced until the end of April (the time of writing). My aim is not to insist on solutions, but to draw a clear picture of the people who stitch the clothes you wear, who are, by far, the most vulnerable part of the whole supply chain; with a view to following up with a more deep and meaningful conversation with sustainable fashion advocates.

To provide some context here, I am the CEO and Founder of Project Work Force, with over a decade of experience in the fashion industry. Our mission is to ensure safe workspaces for garment workers within the informal sector, based in Dhaka, Bangladesh. We supply clothes to retailers across Europe and America, emphasising the need for ethical structures in the garment industry.

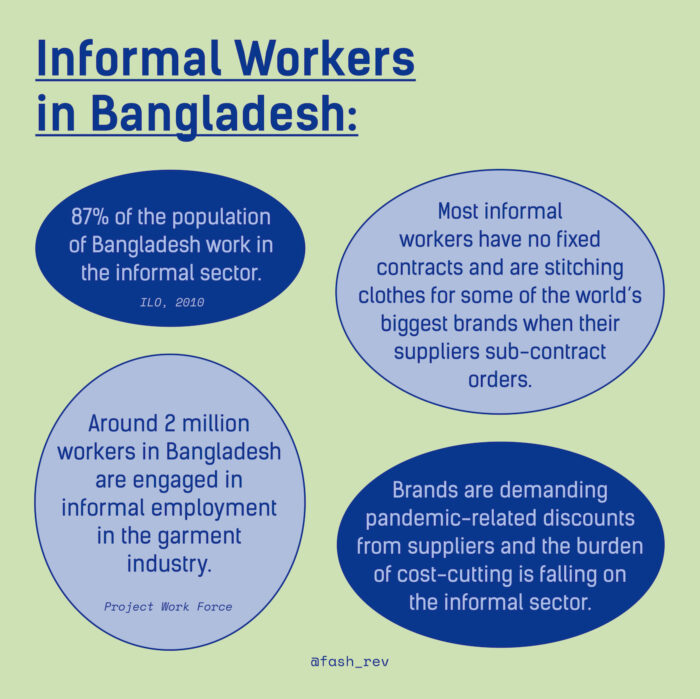

According to our research, there are over two million workers in the Bangladeshi garment industry working in the informal sector; the majority of them stitching workers with no fixed contracts, employed by factories that take sub-contracts from export manufacturers. These are the factories supplying to well-known brands with garments when their direct vendors are unable to fulfil their orders, typically because order volumes are bigger than their capacity, or smaller than their minimum order. In some cases, they are simply looking for cheaper alternatives.

When the first COVID-19 alarms sounded in late December, the impact on the fashion industry was quietly starting. Without clear indications of the consequences of COVID-19 spreading, we sent a team including our Head of Business, Head Designer and Head of Merchandising on a trip to China in January in order to seek out fabrics for Spring/Summer’21. When they returned what they had to say was frightening. China was surprisingly empty and there was restricted entry into Hong Kong. But we put some of that down to the start of Chinese New Year and carried on with our work.

At the end of January when we started booking in our initial orders for Winter ‘20, we received news that our Chinese suppliers were remaining closed for an additional two weeks after Chinese New Year. This prompted a very quick response, shifting fabric production from China to Turkey and India, since there were clear concerns about how reliable suppliers in China would be going forward.

In February, we had booked a record number of orders for immediate deliveries for Spring/ Summer 2020 and Autumn/ Winter 2020. The assumption was that this novel virus would impact China only and we remained in contact with our mills, there was still little indication of the wider impact to come. Orders kept coming in and we adapted.

Then the situation began to escalate. By mid-March we were told by our buyers in Italy, Canada and the US to put all shipments on hold. The same orders that needed to be rushed through one month previously, now completely stalled. This was communicated with generic emails stating that goods that were ready to ship would not be collected and winter 2020 orders would likely be cancelled. A few days later 80% of our Autumn/ Winter 2020 orders were cancelled, even though these were now in production in factories, with payments already made and production already in progress.

With it becoming clear that payment and collection of these finished goods was not going to be forthcoming, it was announced in Bangladesh that over 1 million garment workers, in the formal sector, would not receive their salary. The government quickly stepped in and announced a loan funding plan so that factories would keep their workers on salary.

On 25th March we called 64 factories in our network who employ over 15,000 workers to find out their contingency plans. The plan, we were told, was to layoff 100% of their workforce by the end of March. Most of the factory owners turned their phones off, they had no alternative.

What this has done to garment workers, who live hand to mouth, has been staggering. These workers cannot work from home. With no government funded income, the prospect of zero wages poses a greater risk than that of COVID-19. Thousands of skilled labourers are willing to work regardless of the risk, to ensure they’re able to pay for food and rent for their families. Independent organisations have attempted to combat this crisis with mass rice deliveries.

By the end of March, all governments in Europe and the United States had declared large scale stimulus packages and interest free loans for businesses to support their domestic industries. Some retailers and brands that we work with had pounced on this opportunity and reopened their discussion to restart production for winter goods.

However, these new orders were proposed with a condition – prices need to be 20-30% lower than previously agreed. According to the brands, as the global market has much greater supply than demand, prices needed to be cut. Not only that, they had requested that their delivery dates must be met, otherwise the suppliers face the risk of airfreight costs or cancellation.

We had rejected the lower prices and delivery dates and I was threatened with having all future contracts cancelled once the lockdowns are relaxed and business reopens. See, in the world of fashion, the retailer and brands wields all the power as supply far outstretches demand and the products can be easily replicated.

How can a supplier confirm these reduced prices and stringent delivery dates when you do not know how many working days you have between now and your delivery dates?

Well, you go to the informal sector and get them to do it.

At the time of writing this article, Bangladesh has officially extended the lockdown till 16th Mayand further extensions are highly likely. However, these rules don’t really apply to the informal sector.

Due to the extreme price pressures from buyers after the markets reopen, most export factories will not be able to accept such low prices because they have high fixed costs. However, wages in the informal sector are simply determined by demand and supply, market mechanisms with no regard for working conditions. Workers within the informal sector will take large pay-cuts because they are desperate and need to feed themselves, allowing suppliers to meet the lower prices set by the buyers.

If the situation continues and more factories in the formal sector go bankrupt, then more workers will be forced to move to the informal sector, being paid well below minimum wage to fulfil richer countries’ thirst for cheap clothes.

No one knows the exact timeframe on this. We predict this shut down might mean no income for these workers until October. There is no financial aid being offered from the government to the informal sector and no support from the buyers that have depended on these workers for decades. We are facing a very severe food shortage. But the term food shortage is inappropriate, there is no shortage of food, the reality is there is plenty of food to go around, however these individuals will have no purchasing power to access any food. It costs on average 30 pence (38 cents) a day to feed one person in Bangladesh, with £5 being enough to last one person 2 weeks. In these uncertain times, one thing that is certain is this is a problem that should be and could be prevented.

You can find out more about Project Work Force and how they are working to support garment producers through the current crisis here.

If ever there was a doubt, these past few weeks of the CoViD-19 outbreak have brought into focus the globalized and interconnected nature of our lives, societies and economies. It is not surprising therefore, that the main tool being used to counter the spread of this global pandemic has been to initiate the exact opposite of how our world works right now – which is to undertake an unprecedented scale of shutdowns and lockdowns. These measures are not only curtailing the flow of people but also (non-essential) goods and services. Disruption to the travel, hospitality, restaurant, events, sports and entertainment industry have been noticed by all of us. However, the deeper and somewhat unnoticed impact has been the sudden disruption across various global supply chains.

The reverberations of stores shuttering down in New York or Paris have of course been felt by the local economies and workforce but its impact on factories and workers in Tirrupur and Dhaka has been equally significant. Brands have been cancelling orders across their global supply chains, in many cases, orders which were in transit or ready to be shipped or in very advanced stages of production have also been cancelled. As brands cancel their current and future orders to protect their interests, once again the economic and social burden is being disproportionately felt by some of the most vulnerable in the supply chains — the workers in the textiles and garment factories, and amongst them, most acutely by those on the margin- the contract labour, daily wage workers and piece rate workers. Cancellation of orders resulting in immediate loss of current and future wages, particularly in a time of a major public healthcare crisis where the governments are mandating a lockdown for weeks, is a recipe for mass-starvation. To avoid this, local governments will need to step in, despite already stretched public funding and provide critical food security.

The outbreak of the pandemic has also brought to the fore tensions between the need to protect one’s health and ensuring public health safety and the need to earn a livelihood. This challenge is being felt across factory floors to the farm gates. While most of the cotton had been harvested and sold by farmers across India by January to early February, those fortunate to have access to irrigation are currently in the final stages of their Rabi crop cycle (winter crop cycle). I recently spoke with Mr. Sailesh Patel, a farmer and the CEO of a Fairtrade certified cotton farmer producer company RDFC (Rapar & Dhrangadhra Farmer Producer Company). During our conversation, I learnt that farmers in Kutch (a region of the state of Gujarat, India) grow a long duration variety of cotton known as Deviraj which is typically harvested across mid-March to end April. These farmers are now facing the unenviable choice between either leaving their cotton fields untended and facing crop loss or risking breaking the government notification on the public shutdown and their own health to harvest the cotton. Other cotton farmers in the state who had planted the early harvest varieties of cotton are currently in the middle of wheat and cumin cultivation in the Rabi crop cycle. They too are concerned about crop loss, particularly in the face of climate change and the unseasonal rain that the region is facing. An additional concern that Sailesh Bhai shared was that even if the farmers were to somehow successfully harvest their crops, they would be unable to sell their produce as local mandis (agricultural markets) and buyers would also be following the shutdown rules. With all local supply chains having been brought to a halt and the pandemic showing no signs of abating, will we be in an ironic position where farmers would not receive a fair price and lose income (whether due to wastage or lack of harvesting capacities) for products which are increasingly becoming scarce and expensive in the urban hubs of our countries?

A similarly dire situation is being faced by farmers who don’t have access to irrigation and are cultivating crops (including cotton) in the rain-fed regions of India. Most of the farmers from such regions typically migrate to urban areas to work as daily wage earners for part of the year (January to May) when their lands lie fallow. They return in June to plant their fields before the monsoon season hits their region. With the onset of the CoViD-19 in India and shutdowns being followed by most small and micro enterprises – in line with the government notifications – the migrant workforce has been left stranded. Not only are they losing income but many do not have means to take adequate shelter in this period of shutdown. I spoke with representatives of the Pratima Organic Grower Group of cotton farmers based in the Bolangir district of Orissa, India and was told that some of their members who had migrated to states like Gujarat and Maharashtra during the off season were stranded, unable to even obtain food. Such stories of despair are not isolated and really bring to the fore the devastation to communities and livelihoods that the CoVid-19 outbreak is wrecking. Last week, India saw the desperate reverse migration of the migrant workforce from urban hubs which had shut down overnight, leaving most of them without food and in some cases, shelter. Many of the migrant workers are attempting to walk hundreds of kilometers back home to the “safety” of their villages while tens of thousands of others in places like Delhi, vied with one another in a frenzied scramble to board buses to the nearest towns to their villages. One can only hope that the workers reach home safe and that the CoViD-19, which had thus far been concentrated in urban hubs, does not make the journey to rural India. Only time would tell. What still remains is the need to ensure that these migrant populations and their dependents get access to sufficient food during the remaining part of the shutdown.