Tomorrowland: how innovation and sustainability will change the fashion panorama.

On Wednesday, 24th April 2019, Fashion Revolution hosted our fifth annual Fashion Question Time, a powerful platform to debate the future of the fashion industry during Fashion Revolution Week. This year Fashion Question Time was hosted for the first time at the V&A museum and opening the event up to the public for the first time. The theme this year was Tomorrowland: how innovation and sustainability will change the fashion panorama.

Chaired by Baroness Lola Young of Hornsey, this year’s panel brought together leading figures across government and the fashion industry to discuss the future of the fashion industry.

Attendees included high-level fashion industry representatives from across the sector, global brands, retailers, press, MPs, influencers, and NGOs. Panelists included Mary Creagh, MP and Chair of the Environmental Audit Committee; Laura Balmond, Project Manager, Ellen MacArthur Foundation; Mark Sumner, Lecturer in Sustainability, Fashion & Retail, University of Leeds, and Hendrik Alpen, Sustainability Engagement Manager, H&M Group.

After a welcoming speech from Tim Peeve, an opening speech was made by Sarah Ditty, Policy Director for Fashion Revolution:

“There is an ocean of truth lying undiscovered before us when it comes to the fashion industry of tomorrow. We urgently need to focus on innovation and we need sustainability to be scaled up.”

Below we have selected some questions and answers that were discussed over the 1 hour ½ debate during Fashion Question Time 2019 at the V&A:

Olivia Shaw, Campaign Support Officer for #LoveNotLand

fill and London Waste & Recycling Board asked:

“In a world with finite resources, why does the fashion industry waste around three quarters of what it creates and how are we going change this model to create a fair system for all?”

Laura Balmond, Project Manager, Ellen MacArthur Foundation: It’s not possible to continue as we go on… The amount of clothes produced is rapidly increasing – and we are using clothes 40% less. Less than 1% of materials are going back into fashion we make… We need a huge systemic rethink .. I believe that the circular economy will be business-led. We need businesses to get behind this common vision… The current system doesn’t work. The leaders will continue to push ahead – will the others exist in 5 years time?

Mark Sumner, Lecturer in Sustainability, Fashion & Retail, University of Leeds: Technically there are lots of solutions but there’s no motivation… We have the opportunity to change this and legislation plays an important role. The fashion industry has been around for thousands of years. It plays an important role in self-esteem and identity, plays an important part in our lives. But we can’t stick with the model we have at the moment, we need to change. The Modern Slavery Bill is a good starting point but we need more legislation. More innovative structures in place to penalise businesses – the responsibility needs to be across the whole system.

Mary Creagh, MP and Chair of the Environmental Audit Committee: The current fashion industry model promotes over consumption and under utilisation. My concern is that the policy space in this country, which has historically been a leader on these issues, has been crowded out by the Brexit psychodrama and the space for creative and necessary responses to this is being handed to us. We’re in a unique situation where the public is dragging the Government. We debated the environment twice in Parliament twice yesterday so things are changing but we all need to think about our overconsumption… We also need to strengthen regulation to require greater executive level accountability for tackling modern slavery and reducing greenhouse gas emissions in business and supply chains.

Hendrik Alpen, Sustainability Engagement Manager, H&M Group: Moving to a circular model makes business sense. Right now, H&M operates one of the biggest global take-back schemes.

Sarah Ditty, Fashion Revolution, Policy Director on behalf of Labour behind the Label asked:

The one safety initiative that came out of the Rana Plaza collapse, the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh, is at risk of being expelled from the country at the moment, putting all the progress made in the last six years at risk. At the moment over 50% of the factories still lack adequate fire alarm and detection systems and 40% are still completing structural renovations, these life-saving remediations need to be overseen by the Accord. With the Accord under threat, how can innovations in transparency create a better future for garment workers?

Laura Balmond, Project Manager, Ellen MacArthur Foundation: With innovations around transparency, relies purely on the information that is inputted at the very beginning. So, this then raises the question of how do we verify that and how do we ensure the information you are receiving is correct? Therefore, what are the financial incentives to improve the system? We must incentivise accurate data inputting.

Hendrik Alpen, Sustainability Engagement Manager, H&M Group: The Accord is a very well working mechanism. So, we as a brand, and other brands hope it will continue. Last year 98% of our suppliers were compliant with the Accord’s requirements, and this year, it will be 100% compliance. You talk about incentives, so that’s a sort of incentive we can create to get something back for the work we are investing, besides, you know, it’s the right thing to do. This can also create a level playing field between brands and this is very crucial to make informed choices.

Mary Creagh, MP and Chair of the Environmental Audit Committee:

The real costs of what goes into those clothes are not truly priced. We will only have change if we price clothing based on the material, the labour, and carbon emissions. Those costs are currently passed onto the countries of production… Currently, it’s down to little NGOs to police big brands. Footlocker doesn’t provide an anti-slavery statement on their website, for example… We must make accountants and CEOs accountable for slavery and emissions. Anyone with a pension fund can buy shares in a business, and as a shareholder, you can go to AGMs and to put pressure on these brands.

Sara Arnold of Extinction Rebellion asked:

To have a chance of avoiding the worst effects of the climate and ecological collapse, we must get to net zero carbon by 2025 and halt the loss of biodiversity. The mobilisation we need is unprecedented and as an industry, we should be declaring climate and ecological emergency and acting as so. If this was treated as the emergency that it is, would there be any place for fast fashion? Would there be a place for fashion at all?

Hendrik Alpen, Sustainability Engagement Manager, H&M Group: Obviously, it is hard to say we shouldn’t exist! But I can relate to the thoughts. So, our job is to reduce the impact of what we do. So that’s why we set the goal to be climate positive by 2040, that may be too late, but we are discussing timelines. We have made changes across our stores, and office to be powered by renewable electricity. So, the challenge we have is how do we bring that into the supply chain? And our first goal is to have a climate neutral supply chain by 2030. That’s a huge challenge, we don’t know how to do that, but that’s the challenge we are taking on and we have to take on. Then the question is how can we continue to operate with such a business model which still brings fashion to the people but how do we do that in a better way? Our business model is based on selling products and it still will be for a while and on the other hand, that means jobs for people, joy for people but we need to find a different way.

Laura Balmond, Project Manager, Ellen MacArthur Foundation:

Think of the global population, what do people want, what do people need. Firstly, we need clothes, but then we have a prospect of fashion. Fashion is creative and meets a variety of needs of the people. So you’ve got on the one hand, Instagram bloggers who wear many different outfits and that’s how they’ve learnt to operate. And that’s okay, we don’t want to stifle creativity or fun. At the opposite end of the spectrum, you’ve got the guy that’s had his pair of Levi’s and loves them and doesn’t want them to ever wear out and he’s set for life. So how can the fashion industry rise to the challenge of meeting both these needs and still continue to exist? This can lead to interesting things coming out of this, for instance, an organisation that curates a digital wardrobe, so why do they necessarily need to own clothes at all…This is the end where rental models, swapping will be the way to keep clothes in use for as long as possible, just not with the same person. Then, on the other hand, we need to create well made, durable and repairable clothing. And that’s the challenge for the fashion industry: how can it rise to better meet the needs of the consumers?

Mark Sumner, Lecturer in Sustainability, Fashion & Retail, University of Leeds:

We’ve got 11 years to solve climate change, and I suspect it’s going to be less than that. So I agree, that it’s not fast enough. But I think you need to understand that its systemic part of culture and the part that the fashion industry plays in it. Fashion plays a really important role in our lives, for self-esteem, identity, it’s about projecting our position in society. It a really important part of our lives… I think it’s really interesting when people talk about fast and slow fashion, I go around fabric mills and garment factories, you can see excellent best practice happening in fast fashion supply chain and at the same time, around the corner you see absolutely diabolical conditions in factories supplying to luxury brands, sometimes run by the mafia. So, to think that luxury, fast fashion and slow fashion are different concepts is false. I think what we need to be looking at is brands and retailers that are doing good things, H&M, for example, are trying lots of different models, they haven’t got the answers yet but at least they are trying. Some brands out there don’t even know they have to ask the question about climate change, it’s not on their agenda at all. Those organisations are the ones we really need to metaphorically give them a kick. Different business models need to be developed but that does require significant change, so it’s also about changing the way we behave.

Mary Creagh, MP and Chair of the Environmental Audit Committee:

Thank you [to Extinction Rebellion] for creating the operating space for MP’s like me, who have always been a bit of a lonely voice, to become normalised.

But also, while there is a climate emergency, there’s also a social emergency on hand. And we need to tackle both of these things together. And switching to a low-carbon economy, we have to make it adjust transitionally, we have to make sure we don’t create winners and losers, so that fashion shouldn’t just become something for rich people to enjoy. So, when we look at how we are going to transition, we have got problems with our transport, in agriculture and the way we fuel our homes. So those are the three policy challenges for government. Had we moved from our over-consuming society very quickly, we aren’t going to get to net zero by 2025. The science will tell us what to do to get to net zero by 2050, and then in five years’ time to 2040 and then we’ll aim to get there for 2035. We have wasted the last 10 years, we’ve had no new policy in this country to change behaviour and we’ve done some policy mistakes along the way. I think fashion needs to set out it’s roadmap to net zero. It needs to say how we get to net zero and the target needs to be legally enforceable and not just voluntary.

Dr Mark Sumner, Lecturer in Sustainability, Fashion & Retail, University of Leeds:

This isn’t just about fashion, it’s a culture of consumption. There are brands doing good stuff who are being lambasted by the press and the ones that aren’t doing anything are slipping into the shadows.

Closing Fashion Question Time 2019, Orsola de Castro, co-founder of Fashion Revolution, made a powerful closing speech:

“There is absolutely no excuse anymore. We all have to do what is required of us as people, people working in companies, in governments, in education, in the media, and at home. We have to fight the system and we have to fight our lifestyle. We can’t do this without information and we can’t access verifiable, comparable and understandable information without transparency and public disclosure… We have to move from a culture of exploitation to one of appreciation and place respect for resources and for each other before every deed and every process.”

The other questions asked were:

Antonio Roade, Senior CSR Manager, New Look asked:

Technology will be vital to transition towards a circular economy; and we keep on seeing big companies investing millions collaborating with different research institutions; in different areas and often with no clear outputs. How do we coordinate different initiatives and who should be taking the lead on this (research institutions, governments or brands)?

Elle L, Artist, Expert Advisor in Fashion and Media to United Nations Environment Programme asked:

As we know, fast fashion uses a lot of synthetics which we in the room and the government now know to be highly toxic and damaging to the environment — do you think that a tax can and should be implemented to minimise or how do we phase out the amount of synthetics produced?

Julie Hill, Chair of WRAP asked:

What are the best tools to drive resource efficiency and transparency in the fashion supply chain?

Jennifer Eweh, Designer and Entrepreneur, Eden Diodati asked:

What are the opportunities and challenges involved with automation, blockchain, and artificial intelligence being used within the fashion supply chain?

Siobhan Wilson, Owner, The Fair Shop asked:

Small business and organisations have been driving change in communities across the country and beyond in making, repairing, reinventing and reusing. How can these businesses be nurtured and supported more here in the UK, so they can flourish at a greater scale and gain further exposure to a mainstream fashion audience?

Jasmine Hemsley, Cook, Author and wellness expert, asked:

What will our future look like without sustainable fashion being commonplace?

A very special thank you to the Edwina Ehrman for opening the V&A to Fashion Revolution’s Fashion Question Time and to the rest of the V&A team for your efforts in making this event a success. And a thank you to Sienna Somers and the rest of the Fashion Revolution team for organising this event.

All images Copyright Rachel Manns / www.rachelmanns.com / @rachel_manns / Rachel Manns is an internationally commissioned freelance photographer based in London, UK. She has spent the last decade shooting for a range of clients all over the world. She has a strong passion for sustainability and human rights. With fierce ethical values and a beautiful visual style, Rachel’s work perfectly intertwines the two. Her aim is to use her camera to aid positive change globally, whether that’s politically or commercially, whilst never compromising on aesthetic. Get in contact for rates.

In Autumn 2018 the Environmental Audit Committee wrote to sixteen leading UK fashion retailers, among them M&S, ASOS and Boohoo, asking what they are doing to reduce the environmental and social impact of the clothes and shoes they sell. Today they released their Interim Report on the Sustainability of the Fashion Industry.

Fashion Revolution welcomes the UK Environmental Audit Committee’s findings of their inquiry into the sustainability of the fashion industry. We too want to see a thriving fashion industry in the UK that employs people, inspires creativity and contributes to sustainable livelihoods in the UK and around the world. We agree with the Environmental Audit Committee’s conclusion that the global fashion industry is exploitative and environmentally damaging and that brands and retailers have an obligation to address the fundamental business model.

This report states “We believe that there is scope for retailers to do much more to tackle labour market and environmental sustainability issues. We are disappointed that so few retailers are showing leadership through engagement with industry initiatives.”

Fashion Revolution believes that fashion brands and retailers should sign up to pledges and multi-stakeholder initiatives which are working towards improving workers’ rights, paying a living wage and striving towards a closed loop system. They should also use our Transparency Index as a tool to disclose more about their social and environmental policies, practices and impact both within their companies and throughout their supply chain.

The Committee believes that “The fashion industry’s current business model is clearly unsustainable, especially with a growing middle-class population and rising levels of consumption across the globe. We are disappointed that few high street and online fashion retailers are taking significant steps to improve their environmental sustainability”. Brands are criticised for inadequate sustainability actions and initiatives. The report concludes that recycling waste and complying with the Government’s Carbon Reduction Commitment is not sufficient to offset the environmental damage caused by the fashion industry.

We believe that the fashion industry in the United Kingdom and globally needs far reaching systemic change in order to tackle poverty, inequality and environmental degradation and greater transparency is the first crucial step towards solving its human rights and environmental crises. Our Fashion Transparency Index research has shown that some major brands and retailers are making significant efforts to tackle these issues in their companies and across their supply chains, whilst at the same time far too many large brands and retailers are turning a blind eye. Increased transparency means issues along the supply chain can be identified, addressed and remedied much faster. Greater transparency also means best practice examples, positive stories and effective innovations can be more easily highlighted, shared and potentially scaled or replicated elsewhere.

In an Ipsos MORI survey of 5,000 people across the five largest EU markets published by Fashion Revolution in November, consumers told us they want to know more about the social and environmental impacts of their garments when shopping for clothes and they expect fashion brands and governments to be doing more to address these issues. 77% strongly/somewhat agree that fashion brands should be required by law to respect the human rights of everybody involved in making their products, 75% strongly/somewhat agree that fashion brands should be required by law to protect the environment at every stage of making their products. The majority of people surveyed believed governments should be responsible for holding fashion brands to account for disclosing information about the way their products are made, what suppliers they are working with and how they’re applying socially and environmentally responsible practices in their supply chains.

It is clear that greater government intervention will be necessary if companies are to be held to account for the impacts of their practices on people’s lives and the environment. We want the U.K. Government to pass mandatory due diligence laws, building upon the recent regulatory examples in France and Switzerland. Ultimately, if the UK Government is serious about improving human rights, social impacts and environmental sustainability in the fashion industry, then it must rewrite the rules of the economy so that shareholder profit is no longer prioritised above the protection of our ecosystems and the health and wellbeing of our communities.

The Environmental Audit Committee is launching an inquiry into the sustainability of the fashion industry.

The Committee will investigate the social and environmental impact of disposable ‘fast fashion’ and the wider clothing industry. The inquiry will examine the carbon, resource use and water footprint of clothing throughout its lifecycle. It will look at how clothes can be recycled, and waste and pollution reduced.

Mary Creagh MP, Chair of the Environmental Audit Committee, said:

“Fashion shouldn’t cost the earth. But the way we design, make and discard clothes has a huge environmental impact. Producing clothes requires toxic chemicals and produces climate-changing emissions. Every time we put on a wash, thousands of plastic fibres wash down the drain and into the oceans. We don’t know where or how to recycle end of life clothing.

“Our inquiry will look at how the fashion industry can remodel itself to be both thriving and sustainable.”

The growth of the fashion industry

According to a 2015 report from the British Fashion Council, the UK fashion industry contributed £28.1 billion to national GDP, compared with £21 billion in 2009.[1] The globalised market for fashion manufacturing has facilitated a “fast fashion” phenomenon; cheap clothing, with quick turnover that encourages repurchasing.

Environmental impact of clothing production

Clothing production consumes resources and contributes to climate change. The raw materials used to manufacture clothes require land and water, or extraction of fossil fuels. Clothing production involves processes which require water and energy and use chemical dyes, finishes and coatings – some of which are toxic. Carbon dioxide is emitted throughout the clothing supply chain. In 2017 a report by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation on ‘redesigning fashion’s future’ found that if the global fashion industry continues on its current growth path, it could use more than a quarter of the world’s annual carbon budget by 2050.

Environmental impact of purchase, use and disposal

Synthetic fibres used in some clothing can result in ocean pollution. Research has found that plastic microfibres in clothing are released when they are washed, and enter rivers, the ocean and the food chain.

Sustainability issues also arise when clothing is no longer wanted. A report by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation found that the growth of clothes production is linked to a decline in the number of times a garment is worn. Clothes disposed of in household recycling and sent to landfill instead of charity shops have an environmental impact, such as contributing to methane emissions. Charities have complained that second hand clothes can be exported and dumped on overseas markets. The UK Government has a commitment to ‘Sustainable Production and Consumption’ under UN Sustainable Development Goal 12.

Manufacturing in the UK

In recent years there has been a renewed interest in clothing that has been made in Britain. However there are concerns that the need for quick turn-around in the supply chain to facilitate the demand for “fast fashion” has led to poor working conditions in UK garment factories.

The Committee will also examine the sustainability of garment production in relation to the UK’s social and environmental commitments under the UN Sustainable Development Goals. The UK Government has a commitment to ensuring ‘Decent work and economic growth’ by protecting labour rights and promoting safe and secure working environments for all workers under UN Sustainable Development Goal 8.

Terms of Reference

The Committee invites submissions on some or all of the following points by 5 pm on Monday, 3rd September 2018.

Environmental impact of the fashion industry

- Have UK clothing purchasing habits changed in recent years?

- What is the environmental impact of the fashion supply chain? How has this changed over time?

- What incentives have led to the rise of “fast fashion” in the UK and what incentives could be put in place to make fashion more sustainable?

- Is “fast fashion” unsustainable?

- What industry initiatives exist to minimise the environmental impact of the fashion industry?

- How could the carbon emissions and water demand from the fashion industry be reduced?

Waste from fashion

- What typically happens to unwanted and unwearable clothing in the UK? How can this clothing be managed in a more environmentally friendly way?

- How much unwanted clothing is landfilled or incinerated in the UK each year?

- Does labelling inform consumers about how to donate or recycle clothing to minimise environmental impact, including what to do with damaged clothing?

- What actions have been taken by the fashion industry, the Government and local authorities to increase reuse and recycling of clothing?

- How could consumers be encouraged to buy fewer clothes, reuse clothes and think about how best to dispose of clothes when they are no longer wanted?

Sustainable Garment Manufacturing in the UK

- How has the domestic clothing manufacturing industry changed over time? How is it set to develop in the future?

- How are Government and trade envoys ensuring they meet their commitments under SDG 8 to “protect workers’ rights” and “ensure safe working environments” within the garment manufacturing industry? What more could they do? Are there any industry standards or certifications in place to guarantee sustainable manufacturing of clothing to consumers?

Deadline for submissions

Written evidence should be submitted through the inquiry page by 5 pm on Monday, 3rd September 2018. The word limit is 3,000 words. Later submissions will be accepted, but may be too late to inform the first oral evidence hearing. Please send written submissions using the form on the inquiry page.

Diversity

The Committee values diversity and seek to ensure this where possible. We encourage members of underrepresented groups to submit written evidence. We aim to have diverse panels of Select Committee witnesses and ask organisations to bear this in mind if asked to appear.

Further information

- Guidance: written submissions (including information on data protection)

- About Parliament: Select committees

- Visiting Parliament: Watch committees

Membership of the Committee:

http://www.parliament.uk/business/

committees/committees-a-z/commons-select/environmental-audit-committee/membership/

Media Information: Sean Kinsey kinseys@parliament.uk/ 07917 488791

Specific Committee Information: eacom@parliament.uk/ 020 7219 6150

Committee news and reports, Bills, Library research material and much more can be found at www.parliament.uk. All proceedings can be viewed live and on-demand at www.parliamentlive.tv

Photo credits:

Houses of Parliament and Garment Factory in Bangladesh by Carry Somers

Ocean by Ross Miller

In transit from Bangladesh to Manchester, I walked past the luxury stores in Dubai airport, all of which have leather bags displayed in their windows. The spotlights in the store windows shine down on an array of beautiful bags, but I want to shine a spotlight on a darker story which needs to be revealed. The previous day I had visited the tanneries in Dhaka, Bangladesh, where the leather used for many of the world’s designer bags and shoes originates.

Until recently, the district of Hazaribagh housed the majority of Bangladesh’s tanneries. Not only did severe labour abuse, including child labour, take place but decades of untreated chemical waste has poured into the local Buriganga river, affecting local communities and habitat. In particular, chromium from the tanneries has affected fish populations on which the red-listed endangered Ganges river dolphins prey. Concentrations of chromium are up to 100 times the level prescribed by the World Health Organisation for drinking water.

In an attempt to improve conditions for workers and prevent further environmental pollution in the growing leather sector, the government of Bangladesh decided to relocate the tanneries from Hazaribagh to Savar. The move has been beset by delays: initially scheduled for 2005 completion, an article in Bangladesh’s Daily Star newspaper on 8 November reported that the project has been delayed yet again and they are now aiming for completion in June 2019.

Meanwhile, 92 of the 155 tanneries have already been relocated to Savar, most of which have double the land and therefore at least double the production capacity of their previous facilities. However, the infrastructure and utilities for the tanneries are from adequate, whilst facilities for relocated tannery workers do not even meet their basic necessities of housing, health, education and transportation.

I was visiting unannounced, hoping to talk to workers and managers about the environmental and social problems created by the move. I followed a truck piled high with hides into the Savar Tannery Estate. The smell was a good indication we were approaching the tanneries – a powerful odour which intensified on approach.

The roads were not only potholed, but were covered in surface effluent. The Central Effluent Treatment Plant for the new Savar Tannery Estate is not yet fully functional, drainage systems are not in place and tannery effluent is flowing into local drainage ditches and into the Dhaleswari river. According to the Rapid Assessment of Hazaribagh Tanneries report recently published by SANEM, analysis of data and samples collected at discharge points from the treatment plant, as well as from the Dhaleshwari river, have produced alarming results. Everywhere I looked, drainage ditches were visibly flowing with chemical effluent, with one drain running behind a row of food stalls serving meals to the tannery workers. The government shifted the tanneries due to pollution of the river but ultimately the same thing is happening in Savar.

As I walked from the car towards the first factory I spotted something else on the road – animal tails lying discarded on the ground. Solid waste is being dumped in the streets because a protected dumping yard has not yet been set up.

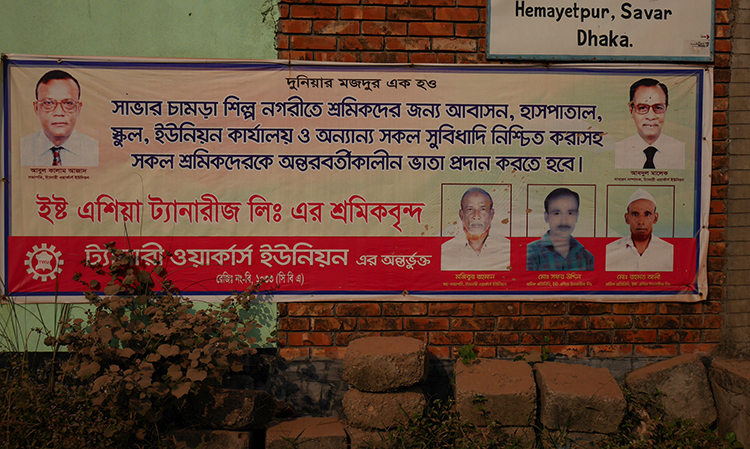

Environmental issues are not the only problems caused by relocating the tanneries before the infrastructure is complete. A sign outside a factory, put up by the Tannery Workers Union, says: “We demand hospital, residence, school, development centre and other benefits should be assured and all past dues should be settled for the workers.”

In the first factory I visited, the foreman was candid about what the urgent improvements needed within the locality. “If there is a serious injury we can’t get the worker to hospital on time. There are no primary healthcare services here. A lot of our workers need ongoing medical support due to skin rashes but we don’t have such facilities here. There is almost no accommodation in the area. There is some but it is expensive so the workers have to commute for 120 taka each way every day (£1.10) and it takes 1.5 to 2 hours. 95% of our country is Muslim yet we don’t have a mosque here.”

I also observed many young workers in the factories, all working without any protective equipment. The sector has an 11% child labour rate, but there is also a problem with young labourers on apprenticeships who should be aged 16 to 17, but often start at 15. Apprentices are allowed to work 30 hours over a six-day week, plus 6 hours maximum overtime across the week, but they are working far more in the tanneries.

Returning to Dhaka, I visited the offices of Awaj Foundation where I talked to Nahidoc Hasan Nayan, Director of Operations, about the tanneries and what steps needed to be taken in order to resolve the myriad problems I had seen that morning. Accommodation costs in Savar are very high compared to Hazaribagh and housing is insufficient, but if workers don’t move the high cost of the commute means their real wages have decreased and they are working below the poverty line. The workers also need schools for their children and medical facilities, which are currently 10-15km from the tanneries. If a factory has 150 workers they should by law have first aid inside the factory but this is not happening. It could easily take over an hour to get to medical facilities due to the traffic jams. Workers are not using personal protective equipment so the risks are high. There is one union for tannery workers, but according to Mr Nayan it is working for the factory owners not the workers.

“Workers are worse off,” stated Mr Nayan,“I found 12 year old boys there last week who have no idea they are working in such a dangerous place.

Part of the problem is that brands don’t come to the tanneries; buyers only engage with the factories,” he continued.

Although the foremen in the tanneries did not know for which brands the leather was destined, I was told in one of the tanneries that the leather would be sent to China and Italy. In Fashion Revolution’s 2017 Fashion Transparency Index which reviews and ranks 100 of the biggest global fashion and apparel brands and retailers according to how much information they disclose about their suppliers, supply chain policies and practices, and social and environmental impact, we found that only 14% of brands were publishing their second tier factories, which sometimes includes tanneries. No one is publishing a list of raw material suppliers, so there is no way for consumers to know where the leather comes from or what animal welfare standards are in place.

The leather and footwear industry is the second largest revenue generator in Bangladesh. Although far behind the Ready-Made-Garment sector at $2 billion USD compared to $28 billion USD, footwear production is expected to become the next area of growth in Bangladesh, putting more pressure on the tanneries as they meet increased demand. The footwear industry comprises 35-50% women but they are not getting maternity leave, nor are workers receiving medical leave or holidays, only festival leave. Not all are getting minimum wage in both the tanneries and the footwear factories, particularly in smaller factories. According to Mr Nayan, only 5-10% of the factories have adequate working conditions.

The move to Savar was planned as a means of improving social and environmental standards but quite the opposite has occurred. So what needs to happen now? Workers urgently need compensation for the wages they lost during the 3 to 4 month transition period from Hazaribagh to Savar when they were unable to work. Transportation must also be organised for workers until affordable, local accommodation is in place. The Central Effluent Treatment Plant urgently needs completion as the current situation is just moving environmental pollution from one site to another. Ultimately, all stakeholders need to take measures to improve working conditions, benefits and health and safety standards so this move has a positive long-term effect on the environment, workers and their families.

As consumers, we can also play a part by asking the question #whomademyclothes, telling brands we need more transparency in fashion supply chains right back to the tanneries and the raw materials.

Many of the social and environmental problems we are seeing in the tanneries are the same ones that beset the garment factories from their inception in the early 1980s until post- Rana Plaza scrutiny started to bring about change. As the leather sector expands in Bangladesh, let’s not make the same tragic mistakes we made with the garment industry.

Carry Somers visited Bangladesh as a guest of the Bangladesh Denim Expo which this year had a focus on Transparency.

For further information on the Rapid Assessment of Hazaribagh Tanneries report, see SANEM

Textile Exchange has set up the Responsible Leather initiative to create responsibility in the leather supply chain.

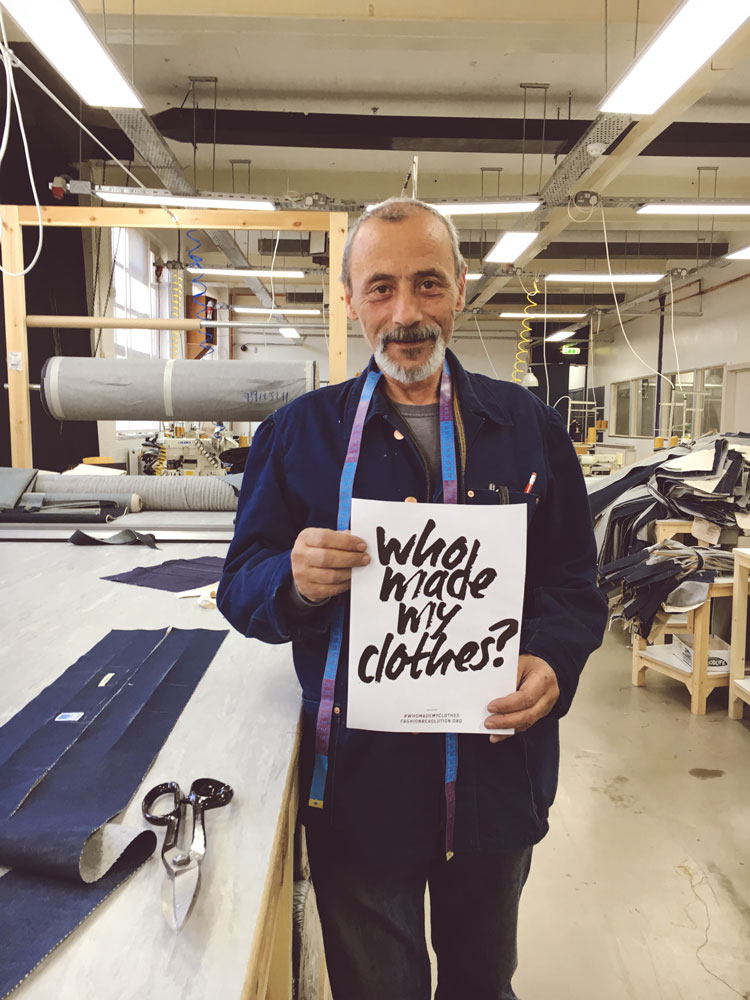

Fashion Revolution’s inaugural Open Studios project was designed to open up the conversation about how clothes are made: to show some of the many processes involved; to give the public who don’t normally have access to the often secretive behind the scenes business of the fashion industry; and to give a platform to some of the designers who are actively finding different ways of producing and selling their collections.

For the designers, this was an opportunity to talk about their clothes and the craftsmanship that goes into making them away from the traditional catwalk format which many new generation designers (and some more established ones) are no longer comfortable with.

A new way of talking about clothes

Fashion is going through a massive shift right now. It’s time to rethink the whole business, from how clothes are made to how they are shown and talked about. Everything is up for question. How many seasons should there be? Is the catwalk show a waste of money (and air miles)? How does a designer communicate most effectively to their community? How does a designer find his or her community?

What is becoming clear is that having an authentic story – whether that’s about the provenance of your materials, the way you make your clothes, your supply chain, or your manufacturing process – resonates with the public. If people trust you and your brand values, they are more likely to become loyal clients.

For young, independent designers, the marketplace is an increasingly crowded one. The gap between the big multi-conglomerate owned brands and independent designers is getting bigger. Even if you have something to say, it is difficult to make your voice heard. But at the same time, the industry is looking for answers and it is the smaller brands who are finding innovative new ways of doing things. Fashion Revolution Open Studios is the perfect place to start those conversations.

Open Studios is an international initiative which is set to expand for 2018. In California, Raquel Allegra hosted a tie-dye workshop in her downtown LA store, showing participants how to dye their own clothes. She also used the opportunity to introduce some of the team who work on the production of her clothes.

Meanwhile, in New York, Audrey Louise Reynolds held an open studio at her Brooklyn Red Hook space showing how she uses vegetable and natural dyes for her delicate pastel pink and turmeric yellow colour palette with advice on how to use her DIY natural dye sachets too. Reynolds has collaborated with Jigsaw as well as Helena Christensen and you can see why her work is in such demand. Read more on WGSN.

And in Jakarta in Indonesia, one of the country’s hottest young designers Wilsen Willim hosted a shirt making workshop at the Indoestri Makerspace. Willim’s signature is the shirt dress which he creates in seemingly endless inventive variations. Willim makes use of the innovative digital startup Kostoom.com which connects him with a network of seamstresses to do his production as piece work which means he, and other small designers, can produce small quantities and scale up or down whilst providing work to tailors working at home.

Studios as creative hubs

Christopher Raeburn embraced the format wholeheartedly. Since moving into his studio space in the old Burberry factory in east London’s Fashion Village, he has been welcoming the public in for studio tours including his archive of vintage military clothing as well as his own collections. He has also started a series of maker workshops where you can learn to cut and sew your own piece of Christopher Raeburn with a little help from his seamstresses and design team. He enjoys welcoming his local community in to see what he is doing.

“I am very proud of my studio,” he said, “and like to open it up as a creative and community hub whenever I can, with regular workshops to teach people how to sew as well as how to repair and customise their clothes and accessories.”

For Open Studios 2017, he hosted a series of open studio tours as well as a “Totes Remade” evening showing guests how to sew their own bag from scrap fabric, and with sponsor Avery Dennison RBIS, created a huge selection box of patches (made from recycled yarn) to decorate the bags. It was quite a party.

“I was very proud to open up the REMADE studio and be a part of Fashion Revolution Week and #whomademyclothes campaign,” said Raeburn. “The tote making workshops were very rewarding events that brought lot of creativity out of the local community.”

Make your own

A real trend that emerged from Open Studios 2017 was a move towards involving the consumer in the process of making their own clothes. Katie Jones held an intimate workshop at her Cockpit Arts space in partnership with Beyond Retro. She taught her participants how to crochet patches to customise or repair existing clothes. It was an opportunity to learn some new skills, meet the designer (and eat lots of Haribos) and learn about her business and craft, but also to make something useful. She’s extending this idea into her practice more and more – keep an eye on her website for in-depth workshops you can join where making your garment is part of the process of owning it. Katie believes that fashion is as much about your relationship with the garment as it is just owning it. It’s not enough to just buy it off the peg (though of course, I’m sure she would welcome that too!) Sign up to get news of her upcoming workshops here

A platform to exchange and share new ideas

As well as workshops as ways to learn a new skill and understand how our clothes are made, Fashion Revolution Open Studios is the ideal platform to discuss and exchange new ideas. We partnered with the Sarabande Foundation for a talk with John Alexander Skelton, one of the most exciting and original new talents to emerge from Central Saint Martins. Skelton looks at his supply chain with forensic detail and creates extraordinary menswear collections using traditional handloom weaving techniques as well as sourcing woven fabrics and knits from local British suppliers. He is forging a new way of producing and selling collections that have, at their heart, an intrinsically ethical and transparent supply chain. Guests were given the rare opportunity to meet John and see his studio, complete with a weaving demonstration. It was a memorable and thought provoking evening, well attended by students, press and industry insiders.

This is Fleur Britten, fashion editor of the Sunday Times’ take on the evening:

The only fashion week worth caring about

There was so much great support and enthusiasm for Fashion Revolution Open Studios 2017, not least from The Debrief who described it as “the only fashion week worth caring about” (we think so, too), as well as Refinery29, Vogue, 10 Magazine, Tank, Sleek, and many others websites and influencers. It was a phenomenal success.

Also taking part in the week’s events were The Autonomous Collections with Kim Stevenson and her ‘ethicool’ workshop where she invited participants to help make a garment; Jodie Ruffle, the extraordinary embroiderer whose recent collaborations have included a project for Adwoa Aboah’s brilliant Gurls Talk Embellished Talk project; Blackhorse Lane Ateliers which hosted a series of open studio events with tours of a unique workshop hand-crafting British made jeans; and the entire textile city of Prato in Italy which staged several workshops and events, coordinated by Italy’s Fashion Revolution country coordinator, the veteran designer Marina Spadafora.

We are in the process of planning Fashion Revolution Open Studios 2018. We have so much to build on, and can’t wait to announce the new line up, hopefully with an event you can take part in near you (or at least online). So stay tuned and thank you for all the amazing support and to all the designers for sharing their stories, their brilliance, and their creativity.

On 26th April 2017, Fashion Revolution’s Head of Policy, Sarah Ditty, spoke at a high-level meeting in the European Parliament “Remembering Rana Plaza – how can we create fair and sustainable supply chains in the garment sector?”

This event came the day before an important plenary vote by Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) on a report pushing rules to curb worker exploitation throughout fashion’s global supply chains.

Good news! The European Parliament passed the resolution 505 votes against 49 with 57 abstentions. The hope is that this will lead to laws, which will ensure better working conditions for the people who make our clothes. Read the speech that Sarah gave yesterday to the European policymakers in support of the report and #whomademyclothes

“Fashion Revolution was born out of the Rana Plaza factory collapse. It started with a group of a dozen designers, academics, writers, fashion professionals and concerned citizens who felt enough is enough. A big push for system-wide change was needed more than ever.

We have since grown to become the largest fashion activism movement in the world with teams in 100 countries, including most European countries. Fashion Revolution Week is a time when hundreds of thousands of people all around the world take to social media and the streets to ask one simple question: who made my clothes? We believe this simple question gets people thinking differently about what they wear. We believe this simple question has the power to push the industry to be more transparent. If brands and retailers are encouraged to answer this question, they must take a closer look at their supply chains.

Last April our campaign reached 159 million people globally through social media and our online media reach alone in April was over 22 billion across more than a thousand articles in the press and blogs.

During this week, we also encourage producers and workers to respond with the hashtag #imadeyourclothes allowing them to stand up, be seen and celebrated, and we ask brands and retailers to respond to #whomademyclothes in order to demonstrate transparency in their supply chain. We are seeing brands increasingly getting involved.

I am here today representing the hundreds of thousands of people who participate in Fashion Revolution’s call for a safer, cleaner, fairer and more transparent apparel industry — particularly young people — of which tens of thousands of us are residents and citizens of European countries, your constituents, to tell you how much we love fashion but that we don’t want our clothes to be made off the back of exploitation, poor working conditions, unjust trade and environmental destruction. That’s a price we truly do not want to pay or worse, to inflict on others. And we believe that the government’s role — at the European level — is crucial to ensure our clothes are never made in this way.

Through our movement we celebrate fashion as a positive influence while also questioning, at times scrutinising, the industry’s practices and raising awareness of its most pressing issues.

We aim to show that change is possible and encourage those who are on a journey to create a more ethical and sustainable future for fashion. But responsible purchasing decisions are not easy to make. As consumers, we just don’t know enough about the impacts of our clothing. This needs to change.

On Monday we launched the second edition of the Fashion Transparency Index. We have reviewed and ranked 100 of the biggest global fashion brands and retailers across a variety of market segments including high street to sportswear to luxury. Brands have been ranked according to how much information they disclose about their suppliers, supply chain policies and practices, and social and environmental impact.

Brands achieved on average 49 out of 250, which is less than 20% of the total possible points. And none of the brands on the list scored above 50% — proving that there is still a long way to go towards transparency.

Overall brands are publishing the most about their policies and commitments — with 98% of the brands publishing at least some relevant social and environmental policies. However, far more space is given to brands’ values and beliefs than to their actual actions and outcomes. Brands score far fewer points when you drive further into detail about the impact of their practices on the lives of workers in their supply chains and on the environment.

The good news is that 32 of the brands are publishing supplier lists, at least at the first tier — where they have direct sourcing relationships and where garments are typically cut, sewn and trimmed. This is an increase from last year when we surveyed 40 big fashion companies and only 5 were publishing supplier lists.

In the past year we have seen brands such as ASOS, Gap, Marks & Spencer, and several others publish factory lists. This is a welcome and necessary step forward. 14 out of the 100 brands are also publishing their processing facilities where clothes are dyed, printed, laundered and otherwise finished at an earlier stage of production.

However, no brand publishes its raw material suppliers so there is no way of knowing where our cotton, wool or other fibres come from, who produces them and under what conditions. Meanwhile only 34 of the 100 brands we reviewed have made public commitments to paying living wages to workers in their supply chains, and only four brands are reporting progress against this goal — progress that has been very slow.

Finally, I would like to stress just how difficult it is to find information about brands’ supply chain and sustainability efforts. Information is often found many clicks away from the homepage of brands’ websites; or you might have to trawl through a 300+ page annual report; or you might find information using all sorts of different industry jargon and presented with an array of different visuals. No wonder consumers find it all so confusing! How are we supposed to make informed decisions about what we buy when the information is either entirely absent or presented in such varied and complicated ways?

We hope the findings of the Fashion Transparency Index encourages more consumers to ask brands #whomademyclothes pushing for more disclosure about the products we buy and wear. We hope the Index influences brands and retailers to start disclosing more information about their suppliers, practices and impacts too. We believe it will.

We hope our research facilitates the good work already being done by NGOs and unions on the ground in producing countries, equipping them with clearer data. And finally and most importantly for today’s vote, we hope that our work demonstrates to you policymakers the pressing need not only for greater transparency from the industry but that this must be underpinned by mandatory due diligence and regulations that have real teeth so that there will be a “race to the top”— and so that the brands who are trying to do the right thing no longer face a market where brands are competing on the basis of the cheapest labour costs or the cheapest materials and processes but rather on the basis of quality, design and creativity.

We, Fashion Revolution, as a voice of thousands and thousands of everyday concerned European citizens and consumers, ask you to vote in favour of the report tomorrow. We hope this is the first step towards a fashion industry in Europe that values people, planet and profit equally.”

Authors: Conor Gallagher and Guy Stuart, Microfinance Opportunities

Four years ago today, a fire at the Tazreen Fashions factory outside Dhaka killed 112 garment workers and injured nearly twice as many. In its aftermath, there was an international outcry calling for greater regulation of health and safety conditions in garment factories across the country. Clothing brands and retailers came together and agreed to better monitor conditions inside the garment factories where their clothes are made; and then, after the Rana Plaza disaster, the Bangladeshi government adopted new legislation to strengthen its regulatory body in conducting safety inspections. As of March 2016, the Department of Inspection for Factories and Establishments had inspected 1,549 ready-made garment factories across the country.[1] Despite these steps, workers in garment factories continue to face poor health and safety conditions not only in Bangladesh but in other major garment exporting countries as well. These poor conditions do not necessarily result in major tragedies such as those at the Tazreen Fashions factory or Rana Plaza, but they nevertheless expose the workers in the factories to unsafe conditions and cause them undue pain and suffering.

Through the Garment Worker Diaries project, research teams in Bangladesh, Cambodia, and India have been collecting weekly data on what garment workers earn and buy each week, how they spend their time each day, and whether they experience any harassment, injuries, or other significant events while at the factories. Though we are still in the early stages of data collection, our project covers 540 workers from across these three countries, and we are hearing from them about the health and safety hazards they face.

Workers in our study have informed us about major events that have taken place in the factories. In Bangladesh, women from two different factories have reported fires. In the first case, a fire broke out during their lunch-break, and workers had to put it out themselves. In the second instance, a fire broke out during a midnight shift and took an hour to be extinguished. No casualties were reported in either case.

In Cambodia, one worker informed us that her factory’s owner had not paid their salary, so she ended up going to stand guard at the factory to try and force him to pay. She then filed a complaint in court against the owner in the following week, again asking him to pay. This was more than two months ago, and the situation has still not been resolved. We have seen similar incidents in Bangladesh. For example, six workers from a factory near Dhaka reported a factory-wide strike as the owner had not paid their salaries on time. This resulted in altercations with police officers, pressuring the owner to pay shortly after the fights broke out.

Not all issues that workers face are major events like fires or strikes; workers have been telling us about some more frequent and persistent challenges they deal with too. Workers in our study have reported on repeated harassment in the work place. These incidents range from being yelled at or insulted to sexual harassment. In Cambodia, workers have been willing to share with us the insults they receive. Some examples include women being called “idiots” or “crazy girls,” while one woman’s supervisor told her that she had “no bright future with [her] careless working style.”

Finally, the workers in our study tell us about the pain they endure because of their work. In India and Cambodia, for example, we have found that workers regularly report instances of chronic pain. Respondents in these countries have common ailments: for India, workers commonly experienced back pain. In Cambodia, workers most commonly have reported suffering from headaches. These types of pain are common among garment factory workers who face uncomfortable working conditions that require them to stand in hunched positions performing repetitive tasks for hours on end. Eventually, these conditions wreak havoc on the workers’ bodies, causing the types of chronic pain that our respondents regularly report. In three extreme cases, workers from India reported experiencing back pain every week, and they have reported that this pain can last anywhere from one hour to several days.

We are still in the early stages of collecting and analyzing the data from the 540 women participating in our study. As the Garment Worker Diaries progresses, we will continue to collect information on what is going on inside garment factories in Bangladesh, Cambodia, and India. We will use interviews and surveys to delve deeper into the specific working conditions that workers face.

We now ask you: what would you like to know about the women who make our clothes and the conditions they face at work?

Tell us by tagging us at @fash_rev #workerdiaries

The Garment Worker Diaries is a yearlong research project led by Microfinance Opportunities in collaboration with Fashion Revolution and with support from C&A Foundation. We are collecting data on the lives of garment workers in Bangladesh, Cambodia, and India. Fashion Revolution will use the findings from this project to advocate for changes in consumer and corporate behavior and for policy changes that improve the living and working conditions of garment workers everywhere.

[1] http://database.dife.gov.bd/

Header photo credit: IndustriALL Global Union

We are the first factory brand to be making authentic premium quality jeans in London for at least the last fifty years. Perhaps the first ever to be making selvedge denim garments in London.

As a community focused enterprise, all factory employees and machinists are shareholders in the company. A place to observe and learn how jeans are created and to visit our allotment growing Japanese indigo to dye the garments.

Name : Mr Husseyin

How long have you been in manufacturing? 40 years

How did you get into manufacturing ? Both my father and grandfather were tailors in Turkey for their whole lives and it influence me to do the same.

How does working here compare to other jobs in manufacturing? It is better than anywhere I have worked before.

What does working here mean to you? I have more opportunities and better life prospects.

Name : Ms Emine

How long have you been in manufacturing? 10 years

How did you get into manufacturing ? I learned to sew In Bulgaria and have been sewing for 10 years now. I’ve lived in London for 4 or 5 years and I am very happy to use the skills I have here.

How does working here compare to other jobs in manufacturing? It is better than any other factory I have worked in. The space is much cleaner and bigger and a much nicer place to work.

What does working here mean to you? It means I can carry on using my skills to earn a good living to make a better life for myself.

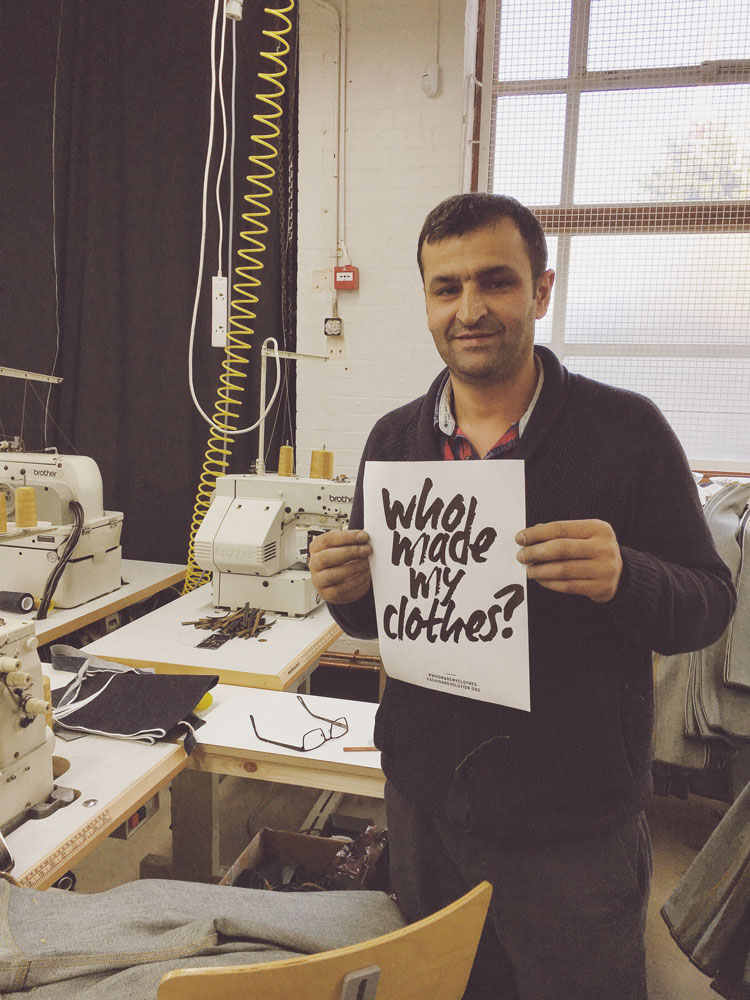

Name : Mr Kenan Habali

How long have you been in manufacturing? 40 years +

How did you get into manufacturing? It is the only thing I know and the thing I know best.

How does working here compare to other jobs in manufacturing? It is better than anywhere I have worked before.

What does working here mean to you? Bread Money

Name : Mr Iliev

How long have you been in manufacturing? 22 years

How did you get into manufacturing? I enjoy the job, I used to work in manufacturing in Bulgaria where I am from.

How does working here compare to other jobs in manufacturing? The conditions are much better and we are treated equally.

What does working here mean to you? It means I can come to work everyday and work hard to earn a good living

Name : Mr Dimitar Conev

How long have you been in manufacturing? 27 years

How did you get into manufacturing? I like the job, sewing and manufacturing is something I enjoy doing.

How does working here compare to other jobs in manufacturing? We are paid a lot better and the working space and conditions are a lot better.

What does working here mean to you? It means I can earn a living and afford a better standard of life.

Name : Ali

How long have you been in manufacturing? 30 years

How did you get into manufacturing ? It is my favourite job. I enjoy sewing and manufacturing more than any other job.

How does working here compare to other jobs in manufacturing ? This is the nicest factory I have worked in.

What does working here mean to you? It means I can earn a proper living.

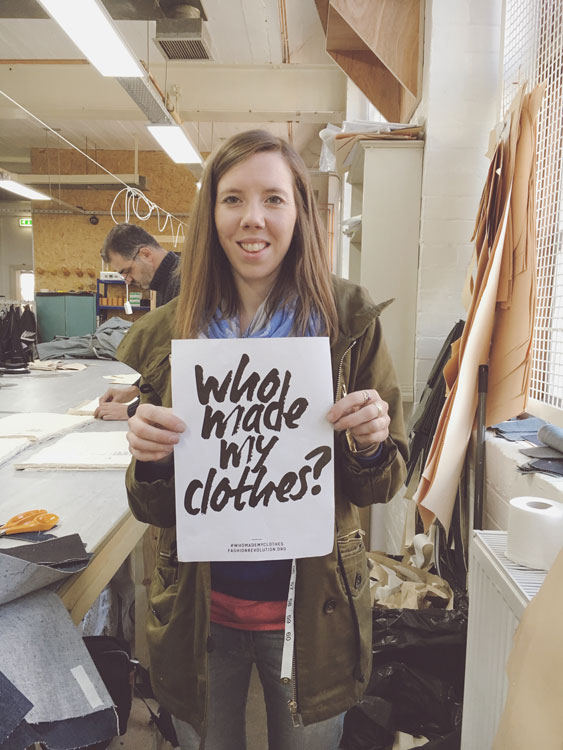

Name : Megan Fisher

How long have you been in manufacturing for ? I have been sewing for 15 years, since I was a little girl.

How did you get into manufacturing ? My mum was always really good at sewing which really inspired me, and I enjoyed textiles classes as school, the passion just grew from there.

How does working here compare to other jobs in manufacturing ? It’s really different because everyone is really honest and open. its a very transparent company, which means we have lots of visitors to see what we do.

What does working here mean to you ? It mean that i get to live an exciting life of living and working in London.

The antithesis of fast fashion, denim jeans are known universally as the quintessential egalitarian garment, with a slow heritage dating back 150 years. Launching in April 2016, the Blackhorse Lane Ateliers is an entirely unique factory brand and manufacturer of superior quality denim goods. Based within a tastefully renovated 1920s factory building in Walthamstow, the brand combines the production of artisan jeans with the establishment of a modern methodology for community living – Think Global, Act Local.

The key element of the Blackhorse Lane Ateliers manifesto has been to challenge the commonly held, modern day attitude of short-term gains, instant gratification and disposability, by implementing a more sustainable, ethical and transparent business model, to the advantage of the consumer. In order to keep the carbon footprint low, each pair of jeans will be produced within their London Atelier and crafted by local Londoners, using only the finest quality selvedge and organic denim, expertly sourced from Europe and Japan.

Ethical Fashion Initiative is a flagship programme of the International Trade Centre, a joint agency of the United Nations and the World Trade Organization. The Initiative links the world’s top fashion talents to marginalised artisans – the majority of them women – in East and West Africa, Haiti and the West Bank. Active since 2009, the Initiative enables artisans living in urban and rural poverty to connect with the global fashion chain. The Ethical Fashion Initiative also enables Africa’s rising generation of fashion talent to forge environmentally sound, sustainable and fulfilling creative collaborations with local artisans.Under its slogan, “NOT CHARITY, JUST WORK.” the Ethical Fashion Initiative advocates a fairer global fashion industry.

Over the past few seasons the Fondazione Pitti Discovery has been setting aside a special area for the rising stars on the world’s economic and creative stage with the Guest Nation project. This edition, in cooperation with the ITCEthical Fashion Initiative, focussed on fashion from Africa with a special event “Constellation Africa”, to promote young and talented designers from the continent.

“I believe that Pitti Uomo is the best platform to showcase these innovative designers from Africa, the continent which hosts the future of fashion and couture“, says Simone Cipriani, Head and Founder of the ITC Ethical Fashion Initiative. “The richness of materials and the beauty of their designs are truly unique. This is where our global society is going: interconnectedness. Global and local dimensions brought together through fashion“.

The four participating brands were:

ORANGE CULTURE // Adebayo Oke-Lawal from Nigeria

Orange Culture is a contemporary menswear brand created by Nigerian designer Adebayo OkeLawal in 2011. The brand combines classic and contemporary western silhouettes with an African edge. Orange Culture fuses Nigerian silhouettes, print fabrics and contemporary urban streetwear. Orange Culture is more than a clothing line, it is a “movement” for a creative class of men that are “self-aware, expressive, explorative and art-loving nomads”. Orange culture has been featured by top fashion magazines and was recently shortlisted by Vogue Talents for Africa and LVMH’s 2014 Young Fashion Designer Prize.

MaXhosa by Laduma // Laduma Ngxokolo from South Africa

MaXhosa by Laduma is a South African knitwear brand founded in 2010 by Laduma Ngxokolo. The South African Xhosa manhood initiation ritual practiced by amakrwala was behind the launch of the brand as Laduma sought to create Xhosa-inspired modern knitwear that would be suitable for this tradition. Since, the Xhosa aesthetic has come to be part of the DNA of the knitwear brand as Laduma has explored and reinterpreted traditional Xhosa beadwork, patterns, symbolism and colours to inspire his modern knitwear line. Through his work, Laduma is an agent of change, shifting and evolving with the changing times and further engaging in the dialogue that keeps pushing traditional culture toward the future.

PROJECTO MENTAL // Tekasala Ma’at Nzinga & Shunnoz Fiel from Angola

Projecto Mental is an Angolan fashion brand, founded in 2004 by creative duo Shunnoz Fiel & Tekasala Ma’at Nzinga, which fuses fashion and art. The brand was created in the aftermath of the civil war as a platform to help reshape Angola’s cultural identity, after the country was ravaged by decades of civil war. Suits with an experimental twist are the signature item of the Projecto Mental brand. Projecto Mental takes an avant-garde approach to tailoring as the designers re-imagine and re-invent the traditional suit for men and women. Strong block colours combined with prints & patterns bring boldness to each design.

DENT DE MAN // Alexis Temomanin from Ivory Coast & UK

Dent de Man is a menswear brand created in 2012 by British-Ivorian designer, Alexis Temomanin. Dent de Man’s approach to luxury style is defined by a mix of classic tailoring with colourful patterned fabric. The Dent de Man lifestyle is defined by freedom, quality and “esthétisme”, empowering individuals to dress for themselves. Self-expression is core to Dent de Man’s philosophy. The brand prides itself on the use of vintage fabrics and celebration of ancient printing techniques, Dent de Man adapts decadent and bold Java prints forming unique garments that allow individuals to own distinctive and irreplaceable pieces. All Dent de Man fabric is carefully sourced and possesses its own story and meaning.

Meet Kady Waylie this International Women’s Day.

Kady is one of West Africa’s 10 million cotton farmers. She and her family grow their own food, but their cash comes from growing cotton.

The farmers’ group in Kady’s village in Senegal began to see benefits of Fairtrade with training courses they were given, to produce better quality cotton, to get higher yields, to improve health and safety.

When it comes to harvest time, they are paid a guaranteed price for their produce, above the market price. And the farmers’ group is also paid the Fairtrade Premium – the extra money that the group decides how to spend, men and women together.

The Premium has been used in Senegal to help many of the women and girls in the community – to build and furnish schools, and to buy packs of stationery, books and schoolbags for students. Some has gone on projects for clean drinking water. Some has been spent helping build and equip clinics, and to train villagers in health care and midwifery.

The processes involved have made groups of cotton farmers stronger and more able to look after their own interests, to deal with government officials, to engage with other groups.

Whilst International Women’s Day represents an opportunity to celebrate the achievements of women around the world, sadly it’s not all good news.

Kady’s cooperative, and many others, are desperate to sell more of their cotton on Fairtrade terms because are not earning nearly enough from Fairtrade sales to lift them out of terrible poverty.

The price of cotton has slumped in the last 30 years, even though the cost of producing it has risen and that means farmers in places like Uganda, India, Kyrgyzstan and West Africa are struggling to survive.

Cotton farmers are at the end of a long and complex supply chain in which they are virtually invisible and wield little power or influence. With high levels of illiteracy and limited land holdings, many cotton farmers live below the poverty line and are dependent on the middle men or ginners who buy their cotton, often at prices below the cost of production.

Practically speaking, farmers selling cotton on Fairtrade terms receive a Fairtrade Minimum Price for their cotton, which acts as a vital safety net and gives the stability that is needed to plan for the future. But it doesn’t stop there. They also earn an extra sum – the Fairtrade Premium – which farmer groups can then decide democratically how to best use, to improve quality and productivity for their crops and social projects such as education and health services, to benefit their communities.

But farmers can only sell on Fairtrade terms if British shoppers continue to ask for Fairtrade cotton when we buy new outfits. Put simply, more brands using Fairtrade cotton means more money goes back to help women and girls in cotton growing communities.

There seems to be a trend in the UK now to demand to know how clothes were made, but not who grew the cotton that they are made from, and this lack of awareness is resulting in desperate hardship.

It would be good we all posed the question at the store till ‘Who made my clothes?’ That way, transparency in the garment supply chain can extend from the London catwalks all the way back to cotton farmers picking the cotton in Senegal.

Do fashion lovers realise that as many as 100m rural households – 90 percent of them in developing countries – are directly engaged in cotton production? An estimated 350m people work in the cotton sector when family labour, farm labour and workers in connected services such as transportation, ginning, baling and storage are taken into account.

To help increase sales for cotton farmers like Kady, fashion brands can now work with Fairtrade Cotton on two ways – either the finished product is certified as Fairtrade, or using the new Fairtrade Sourcing Program, they can commit to sourcing a certain amount of cotton on Fairtrade terms. Whichever route they choose, their commitment to Fairtrade Cotton means better lives for the farmers who grew your cotton.

Start asking questions when you shop for clothes this International Women’s Day and help women like Kady get a better deal so they can celebrate their achievements.

Watch this short film to learn more about cotton farmers in Senegal

Join Fashion Revolution Day on 24 April 2015. Turn an item of clothing inside-out and ask the brands the question: Who Made My Clothes? #whomademyclothes

Together we will use the power of fashion to inspire change

and reconnect the broken links in the supply chain.

My name is Delfina Minchala Guaman, age 79 and 4 months. I am very proud of being almost 80. I am one of the five founding members of the Cañari Panama hat weaving Cooperative.

I was born in Guapan, Cañar. I was born here and I will die here. My father and mother wove hats to support their four daughters. I am the youngest of the sisters; the others are all deceased. When I was one year and six months old my mother died and my father alone supported us with the income from his weaving. He taught me to weave when I was six and I was paid 10 sucres (USD $0.75 cents, about 50p) for each hat. At age twelve I asked a friend to teach me how to weave fine hats so that I could earn 20 sucres per hat.

I married my neighbor when I turned 18 and we had 10 children together. We were very much in love and he was handsome. I am now widowed. Five of my children have died and the five surviving children are all professionals living in La Troncal (a town in the same province). They are two doctors, a nurse, a police officer, and one works in the Ministry of Culture. I have 16 grandchildren ranging in age from 8 months to twenty-two years old. Apart from weaving, I earn money raising cuy (guinea pigs). I have more than 60 cuy. I also have five roosters, three chickens, one dog, and one cat.

Pachacuti work with Delfina’s weaving cooperative

Last year Pants to Poverty ran a national educational programme across 15 FE colleges around the UK called the ‘Pantrepreneur Challenge.’ This programme involved key entrepreneurial skills and the winning team won the opportunity of a life time, the chance to travel to Semla, Odissa, India to visit the Pants to Poverty supply chain. During their trip, the students visited a government funded school which is the beneficiary of the funds and support that the competition generated. They also worked in the cotton fields, lived in the farming community and visited the factory where the pants are made, working on the factory floor as unskilled labourers. They even lived in the homes of the garment workers to truly experience life in their shoes. All participants claimed that visiting these totally uncharted territories ‘completely changed their lives’.

This year, the Pantrepreneur Challenge goes even further, as it is being expanded to cover 18 colleges across the UK. It will also include participating in the Fairtrade fortnight mini march! The competition will then culminate in June at the finals, which will take over Spitalfields market for the day.

To see more photos from the trip, click here

Photography by Christ Storrar