Fashion Revolution cada día, y en particular durante el mes de abril, nos invita a preguntamos #QuienHizoMiRopa? La respuesta parece obvia, pero no siempre está a la vista de todas y todos.

Detrás de cada prenda hay una persona, y cada persona detrás de una máquina de coser tiene una historia. Como equipo Fashion Revolution Chile creemos que es crucial reconocer la realidad de quienes diseñan, confeccionan, reutilizan y arreglan una prenda. Esas personas son la base del sistema que nos viste, y parte importante de la solución hacia un consumo más ético y responsable de la moda.

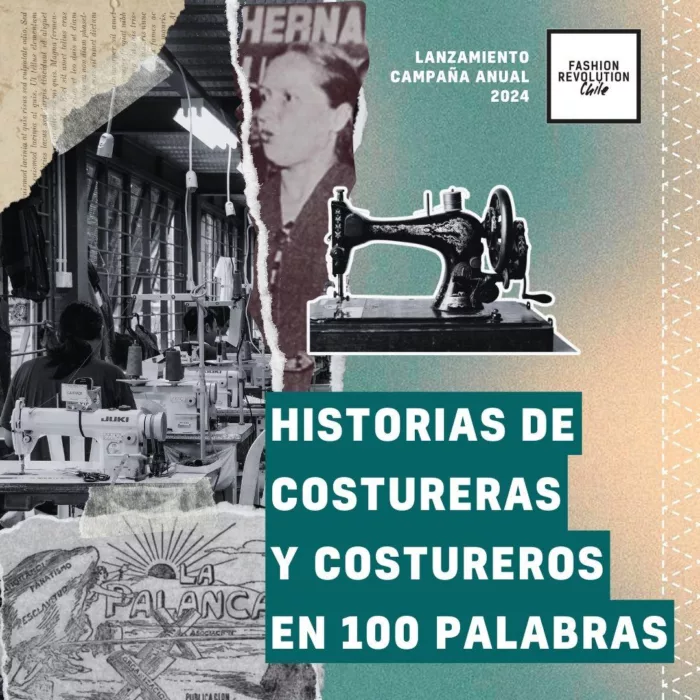

Nuestra campaña territorial 2024 “Historias de costureras y costureros en 100 palabras” nace con la intención de recoger esos testimonios, y así visibilizar la realidad a menudo olvidada de las costureras y costureros que trabajan incansablemente en la industria textil y de la moda en Chile.

Para eso, formulamos la difusión de la campaña y abrimos una convocatoria de libre participación desde el 28 de marzo hasta el 18 de abril. La que fue difundida principalmente a través de nuestras redes sociales y recibió un total de 46 historias.

Sólo en 100 palabras…

Puede ser difícil resumir la experiencia de la costura en tan poco texto, pero fueron suficientes para que algunas personas contaran cuentos, experiencias y relatos totalmente emocionantes. Algunos de ellos, entramados a una larga historia familiar, la herencia histórica del oficio y el esfuerzo que esconde el trabajo detrás de #QuienHizoTuRopa

Al finalizar la campaña, realizamos una selección de historias para exhibir en nuestro evento presencial de la Fashion Revolution Week, el día 20 de abril. Oportunidad donde nos reunimos para dialogar sobre la importancia de trabajar por una industria de la moda más sostenible, territorial y responsable, y donde también los asistentes pudieron disfrutar de seis diversos talleres, tres conversatorios, una exposición de diseño y una jornada de networking.

¡Muchas gracias a todos quienes participaron y contaron su historia!

This post is a translation of a recent Guardian article exploring textile waste, written by journalist Tamsin Blanchard.

A tavalyi évben hatalmas mértékben növekedett a hipergyors divat, amely jelentős szénlábnyommal és hulladéktermeléssel jár. Mérgező mennyiségű poliészter ruha került legyártásra, illetve a szemétbe és ne feledjük, hogy mennyire szoros kapcsolat van a fosszilis tüzelőanyagok és a ruháinkban lévő szintetikus anyagok között.

“A fosszilis divat a fast fashion számos súlyos problémájának a középpontjában áll: olcsó anyagok, túlzott függőség a szintetikus anyagoktól, hulladékválság és az egyre növekvő kibocsátás” – állította a Fossil Fuel Fashion, egy új szervezet, amely a New York-i Klímahéten indult szeptemberben, és olyan szervezetek koalícióját tömöríti, amelyeknek célja a fosszilis tüzelőanyagok fokozatos kivonása az iparágból. A fosszilis tüzelőanyag-alapú poliészter olcsó, és a hipergyors divat kedvelt anyaga, amely továbbra is leuralja a piacot, annak ellenére, hogy júniusban számos kritika érte. A Shein hat divatipari influencert fizetett, hogy látogassanak el kínai gyáraikba és az influencerek ezután elragadó véleményeket osztottak meg a kulisszák mögül. A 66 milliárd dolláros divatmárka továbbra is arra ösztönöz minket, hogy olyan ruhákat vásároljunk, amelyekről nem is tudtuk, hogy szükségünk van rájuk, és amikre valójában biztosan nincs is szükségünk. A versenyfutás azonban csak most kezdődött meg. A kínai Temu nevű vásárlási alkalmazást, -amely a Sheint is megszorongatja a 99%-os kedvezményes ajánlataival-, már több mint 7 milliószor töltötték le, mióta áprilisban elindult az Egyesült Királyságban.

Nem csak rossz hírrel tudok szolgálni. A mezőgazdaság és a divat közötti kapcsolatról még soha nem esett ennyiszer szó; a “regeneratív” a tavalyi év egyik legelterjedtebb divatszava volt. Ahogy Safia Minney, a Fashion Declares alapítója elmagyarázza, a divat nem csak arról szól, hogy a gazdáknak biztosítaniuk kell a szén-dioxidot a talajban, hanem az egész folyamatról – a pamut, a kender, a len, a gyapjú és a bőr termesztésétől kezdve egészen a ruhadarabok életciklusának végéig. A regeneratív divat egyik győzelmére októberben került sor, amikor Justine Aldersey-Williams bemutatta az Egyesült Királyság első saját termesztésű, házi fonású farmerját, amely a lancashire-i Blackburnben termesztett lenből és gyapjúból készült.

2023 volt az az év is, amikor a hulladékkolonializmus szörnyű környezetszennyezése újra a figyelem középpontjába került. Februárban a ghánai Accra Kantamanto piacán működő The Or Foundation, amely a divat szemétproblémájának igazságtalanságával foglalkozik, közzétette a Stop Waste Colonialism (Állítsuk meg a hulladékgyarmatosítást) című jelentését. Ebben kifejtette, hogy “a divatipar a globális használtruha-kereskedelmet de facto hulladékkezelési stratégiaként használja“. Májusban ruházati kereskedők egy csoportja Brüsszelbe utazott, hogy megvitassák a döntéshozókkal a kiterjesztett gyártói felelősségről (EPR) szóló európai jogszabályokat. Fontos, hogy a kantamantói piacot védő szervezeti tag is részt vett ebben a beszélgetésben, mivel a világ textilhulladéka az ő küszöbükön végzi.

Jeremy Hutchison művész egy lépéssel tovább vitte a küszöbön lévő szemét gondolatát, amikor a “fogyasztás utáni imperializmus szörnyetegévé” vált, egy fulladozó, 2,5 méter magas textilzombi, a Dead White Man formájában. Az alkotás a The Or Foundationnel való együttműködésben készült, és a ghánai obroni wawu kifejezésre utalt, ami annyit tesz: halott fehér ember ruhája. A kantamantói piac kereskedői, így emlegetik a globális északról származó selejtes árukészletet. A Dead White Man októberben fellépett a brit textilbiennálén Blackburnben, majd rögtönzött látogatásokat tett pár ruházati beszállítónál, köztük a Marks & Spencernél. Az M&S egyike azoknak a márkáknak, amelyek címkéi gyakran megjelennek Accra strandjain.

Szeptemberben Clare Press, a Wardrobe Crisis podcast alapítója – amely a fenntartható divat iránt érdeklődők számára elengedhetetlen műsora – kiadta legújabb könyvét, a Wear Next-et: Fashioning the Future (A jövő divatja) című könyvét, amelyben számos ilyen problémára kínál megoldásokat. “A túltermelés és a hipersebesség a divatipar két legnagyobb problémája” – mondja. A Fashion Revolution éves Fashion Transparency Indexében arról számolt be, hogy a nagy divatmárkák 88%-a még mindig nem hozza nyilvánosságra éves termelési volumenét. Az Index szerint globálisan annyi ruha van a rendszerben, hogy a következő hat emberöltőnyi generációt fel tudnánk öltöztetni (ha a bolygó nem megy tönkre előtte).

Továbbá, tavaly kezdte el az európai jogalkotás beleásni magát a fast fashion szabályozásába. Decemberben az Európai Parlament az új “ökodizájn” keretrendszer részeként elfogadta az eladatlan ruhák, kiegészítők és lábbelik megsemmisítésének tilalmát, a ruházati cikkek pedig digitális termékútlevelet kapnak. A várhatóan 2026-ban hatályba lépő QR-kód nagyobb átláthatóságot biztosít majd a vásárlók számára az anyagokról, a gyártásról, sőt, még akár javítási tippeket is adhat. Szabályozás nélkül a márkák még mindig nem vállalnak felelősséget termékeikért, az általuk felhasznált anyagokért és ellátási láncukért. A jogalkotás végre elkezdi őket arra késztetni, hogy kollektív lépéseket tegyenek.

Azonban a ruhaipari munkások folyamatos kizsákmányolása sajnos világszerte folytatódott. 2023-ban volt 10 éve, hogy a bangladesi Dhakában található Rana Plaza gyár katasztrófája során 1134 ember vesztette életét, és legalább 2000-en megsérültek, amikor a gyár összeomlott. Most decemberben pedig több mint 50 márka csatlakozott az újonnan kiterjesztett nemzetközi megállapodáshoz, amely hozzájárult a biztonságosabb munkakörülményekhez több mint 2 millió bangladesi ruhagyári munkás számára, 48 aláírta a bangladesi biztonsági megállapodást és 88 a legutóbbi pakisztáni megállapodást.

Az átláthatóság azonban továbbra is hiányzik. Novemberben egy derbyshire-i nő egy kínai rab személyi igazolványát találta meg a Regatta kabátja ujjbélésében. Az ellátási láncokban rejtőző modern rabszolgaság még mindig jelen van a divatiparban, a szegénységi bérezés pedig még mindig az iparági normák közé tartozik. Amint arról a Clean Clothes Campaign beszámolt, idén június 25-én a bangladesi Tongiban halálra verték Shahidul Islam szakszervezeti vezetőt, aki a munkajogok védelmében tevékenykedett. Az új bangladesi minimálbér elleni folyamatos tiltakozások következtében novemberben négy munkás meghalt, és legalább 115 munkás és szakszervezeti tag került börtönbe. Maeve Galvin, a Fashion Revolution globális politikai és kampányigazgatója szerint “olyan messze vagyunk attól, hogy a munkavállalók elérjék a társadalmi igazságosságot, hogy az szégyenletes“.

Ami viszont reménykeltőbb, hogy a fiatalok előszeretettel vásárolnak használtan, másodkézből online vagy vintage üzletekben. A fast fashion divatmárkák látják, hogy a Depop, a Vinted és az eBay a legnagyobb versenytársaik, és elkezdték értékes kiskereskedelmi területüket a használt ruháknak átadni. A Wear Next című tanulmány szerint, miközben a divatfogyasztás felgyorsul, ezzel párhuzamosan a lassú divat mozgalmának felemelkedését láthatjuk, a javítási forradalom (beleértve a javítási és átalakítási alkalmazásokat, mint például a Sojo és a The Seam) és a DIY divat további virágzását. Reméljük ezen az úton fogunk továbbhaladni!

Forrás: theguardian.com

Fordította: Pölz Klaudia

Artículo redactado por Nora Sesmero Andrés, voluntaria de Fashion Revolution.

No estamos tan bien. La diversidad en la representación en la industria de la moda deja mucho que desear. Existen 1.000 millones de personas en el mundo con algún tipo de diversidad funcional que les limita a diario. “La primera vez que asistí a New York Fashion Week fue en 2017. Cuando llegué a la “ciudad que nunca duerme”, se volvió evidente para mí por qué la gente la llamaba así: simplemente no hay tiempo de dormirse cuando debes sortear todas las barreras de accesibilidad para personas con discapacidad”, confiesa Madison Lawson para Vogue México.

Judy Haumann, una activista de larga trayectoria por los derechos de las personas con discapacidad enfatiza: “La gente no nos ve como iguales en sus comunidades, en las escuelas, mezquitas, iglesias, sinagogas, clubes sociales, o lo que sea… Ellos nos ven y piensan ‘¿cómo podría vivir mi vida si fuese así?’”. Es por esta razón que la representación auténtica es algo vital.

En los últimos años, las redes sociales se han convertido en una herramienta con la que personas con discapacidad han podido controlar la forma en que estaban siendo representadas. Mientras se debate y se hacen llamados para una mayor diversidad, el floreciente movimiento body positivity abrió un espacio para celebrar la belleza en diferentes formas.

La modelo Bri Scalesse quedó parapléjica a los seis años tras un accidente de coche que le ocasionó lesiones en la médula espinal. Ella siempre ha demandado una representación de personas como ella, hoy puede representar a través de su trabajo y de las RRSS a todas esas personas que también lo demandan.

https://www.tiktok.com/@briscalesse/video/7171941421375737134?is_copy_url=1&is_from_webapp=v1

El modelo Aaron Phillip en 2018 se convirtió en el primer modelo, transgénero, y con discapacidad en ser representado por una importante agencia, después de que uno de sus tweets se hiciera viral. En un lugar similar está el modelo transgénero, con hipoacusia, Chella Man quien atrajo las miradas del mundo con las fotos que compartió en Internet. Gucci también acaparó los titulares al reclutar a Ellie Goldstein, una joven modelo con Síndrome de Down, que figuró como el rostro principal de su línea de belleza.

“Ya hora de que nos movamos más allá de la tokenización. Necesitamos ver a más personas frente a la cámara, pero también necesitamos verlas detrás. Necesitamos ver gente que se vea como nosotros en posiciones de poder, en todos esos lugares en los que hemos sido históricamente olvidados. Después de todo, ¿qué bien nos hace el ver a alguien que se parezca a nosotros en una campaña, si la marca no puede satisfacer nuestras necesidades? Lo mismo ocurre si seleccionan a una modelo para una sesión de fotos o para un desfile, pero esta no puede acceder a la locación del evento, ni al backstage”, afirma Madison Lawson.

Jillian Mercado le confesó a HOLA: “Resulta difícil lograr trabajar con un grupo de personas o estar en un lugar donde las personas aceptan y son abiertas y también pueden educarse a sí mismas sobre cómo pueden ser mejores y hacerlo mejor para asegurarse de que las diversas personas en su comunidad también pueden sentirse seguros y también pueden sentirse incluidos en esa conversación. Es tan importante poder decir que he podido”.

Sinéad Burke se dirige a las empresas y les advierte de que van a tener que empezar a abrir su lente a la accesibilidad porque el mercado está cambiando. Las empresas que hoy apuestan por el cambio están siendo las pioneras de una era que comienza a acercarse. Es el caso de Chamiah Dewey Fashion, la primera marca de Reino Unido que defiende la sostenibilidad y diseña moda para personas de estatura pequeña.

En otro artículo de Fashion Revolution escrito por Heloisa Rocha, Samanta Bullock exponía: “Hay que eliminar las barreras reales, físicas, digitales y, sobre todo, de actitud”.

“El otro día estaba hablando con una chica que me dijo que solicitó en una tienda de ropa la fila para personas discapacitadas y la dijeron que no tenían. Estaba muy enfadada, evidentemente. Tenemos que tener estas cosas en cuenta. Hay personas que no pueden estar en una fila mucho tiempo esperando”, comenta Marina Vergés, fundadora de Free Form Style.

La ropa también debe representar a las personas y para ello se deben conocer los conceptos de “moda adaptada” y “moda inclusiva”. Hay pequeñas diferencias entre estos dos conceptos: Moda inclusiva es la moda para todo tipo de personas, donde todos los cuerpos están representados, además de la raza, talla, edad o diversidad de género.

Y la moda adaptada, además de inclusiva, hace referencia a la ropa especialmente diseñada para personas con distintas movilidades. La moda adaptada facilita que las personas con movilidad reducida se vistan de forma independiente: cerrar una sudadera con cremallera con un solo brazo, o ponerse un pantalón fácilmente cuando estas en una silla de ruedas (te vistas en la cama o en la silla). La moda adaptada también puede ofrecer aberturas adicionales para que la gente pueda acceder fácilmente a partes de su cuerpo donde normalmente sería difícil de llegar con piezas estándar. La moda adaptada también puede ser ropa que se adapte a la sobreestimulación sensorial. Que tenga en cuenta la carta de colores para personas con poca visibilidad o coordinar un look con una visión daltónica.

En Free Form Style siempre han tenido claros estos dos términos y han diseñado sus colecciones entorno a ellos. Ellos quieren que sus clientes consigan tener autonomía. “Es importante la especialización en la moda. Los emprendedores no piensan en cubrir una necesidad en las personas cuando crean una marca de moda, piensan en cómo podrán obtener más beneficios. Pero eso ya no es posible. La idea es que la moda se adapte al cuerpo, no que el cuerpo se adapte a la moda. Se ha de normalizar la moda adaptada e inclusiva. Basta de pensar en marcas, debemos pensar en la comodidad, no en lo que es tendencia. Debemos incluir a personas discapacitadas en los equipos de trabajo y en el marketing, que se normalice realmente esta necesidad”, confiesa Marina.

https://vm.tiktok.com/ZMFu95Q7R/

Timpers es una marca de calzado de calidad, fabricadas en Alicante, cuya plantilla está formada por personas con discapacidad. Sus valores son la creatividad, derribar los estereotipos, el trabajo en equipo, probar a hacer las cosas siempre, defienden que nuestras capacidades importan más que nuestras discapacidades. “Actualmente, tres de cada cuatro personas con discapacidad, en edad laboral, no trabajan y todavía siguen existiendo desigualdades en temas tan importantes como pueden ser la igualdad de oportunidades, salarial o curricular. Nos hemos propuesto cambiar la vida de estas personas y demostrar que una normalización plena es posible, y demostrar que la discapacidad en los equipos de trabajo no es un inconveniente, sino un enriquecimiento para los mismos y que a las personas hay que valorarlas por sus capacidades y no por sus discapacidades”, afirma el CCO de Timpers, Diego Soliveres.

“Es simple: una prenda inclusiva es cuando todo el mundo se la puede poner, no solo una persona, sin necesidad de adaptarla”, explica Rut Turró para El País. Admite que se las ha visto y deseado para hacer pedagogía con este concepto de diseño universal. En este momento nace Movingmood, una asesoría para empresas textiles que quieran incorporar esta noción a sus procesos productivos. Uno de sus métodos consiste en analizar la accesibilidad de las colecciones y plasmarlo en un panel visual, un cánon que los diseñadores pueden seguir de ahí en adelante. Otra solución, esta para empresas de estampados y color, es el uso de cartas de colores para personas con daltonismo o hipersensibilidad. De 2011 a 2014, Rut Turró visitó 85 entidades e hizo más de 200 entrevistas a usuarios con diferentes diversidades, profesionales, cuidadores, terapeutas y familiares. Identificó nueve funcionalidades básicas de la ropa inclusiva:

- Usabilidad: Fácil de poner y quitar, vestir y desvestir.

- Autonomía.

- Facilidad de cierre.

- Atractivo: la moda y la funcionalidad van de la mano.

- Buen fitting para todo tipo de cuerpos.

- Que sea cómoda y evite las fricciones y presiones.

- Sensibilidad: evite irritaciones en la piel y aporte confort térmico.

- Que permita la libertad de movimientos.

- Que dé seguridad a la persona, que la haga sentir bien, que le suba la autoestima.

Las decisiones que toman las personas que trabajan dentro de las empresas importan mucho. Y más si se contemplan dentro de la industria de la moda, porque esta representa a muchas personas, influye en las decisiones de estas y da de comer a muchas otras. Una industria de la moda más igualitaria es una industria de la moda mejor.

Si quieres continuar leyendo y concienciándote acerca de la actualidad de la industria textil, pulsa aquí.

La contaminación por tintes es uno de los problemas de la industria textil que amenaza el planeta y nuestro bienestar. Utilizamos el agua como si fuera un recurso inagotable pero la verdad es que solo un 3,5% aproximadamente de toda el agua de la Tierra es dulce y está apto para el consumo. El uso intensivo de la tierra, la deforestación, el cambio climático y el mayor consumo de agua dulce por una población y una industria que no dejan de crecer amenazan nuestros ríos, lagos y los depósitos bajo tierra.

La triste história del río Yangtze

En china, más del 80% de toda el agua subterránea está tan contaminada que no puede destinarse ni para usos agrícolas. En el sudeste de dicho país el 70% del agua contaminada es responsabilidad de las industrias textiles de la zona.

El río Yangtze es conocido como el río más largo de China y recibe el 40% del desecho industrial y textil de todo el país. Cada año se lanzan allí más de 25 millones de toneladas de desechos, según la WWF. La industria textil posee vertidos con una alta carga tóxica, provocada por muchos metales como el arsénico o el cadmio, que pueden provocar una mortalidad del 100% a las especies marinas.

El problema de la salubridad ya no solo se encuentra en las ciudades más cercanas del río Yangtze, sino que las zonas más alejadas empiezan a tener problemas con la contaminación. La liberación descontrolada de químicos y tintes ha llegado a modificar el color del agua, donde son normales las mareas rojas, negras o incluso azules.

Río Azul

Para entender la complejidad del problema causado por la contaminación por tintes en las ciudades más importantes en fabricación de tejidos, podemos embarcar en un viaje con el documental River Blue y descubrir la realidad que se encuentra detrás de cada etiqueta. Una rápida pero impactante imagen que nos enseña la realidad de muchos procesos y como actualmente somos capaces de cambiar nuestro impacto en el agua.

Una alternativa: los tintes naturales

Comprendemos la importancia de los colores en nuestras prendas y sabemos que son parte intrínseca y fundamental del proceso de diseño. Por eso, es importante buscar alternativas que no dañen el medioambiente ni nuestra salud. Incluso, el pasado nos puede ayudar en esta búsqueda: hay evidencias arqueológicas de que se han utilizado colorantes textiles desde el periodo Neolítico.

Los tintes naturales son colorantes que se extraen de plantas, insectos y minerales y que tienen la calidad de teñir fibras naturales, tales como: algodón, yute, lana, cáñamo, seda, etc.

Algunas técnicas artesanales de tinte natural

#Ecoprint: una técnica de estampación natural con hojas frescas.

#BundleDye: una técnica contemporánea de estampación natural en que se utiliza el vapor para transferir materiales vegetales sobre la tela.

#Shibori: una técnica tradicional japonesa de teñido. El diseño se consigue moldeando un trozo de tela, creando zonas de reserva y teniéndolo.

Una ayuda de la tecnología

Además de los tintes naturales, la tecnología también nos puede ayudar a disminuir los impactos de la industria textil en la contaminación por tintes. Por ejemplo, ahora ya es posible producir unos tejanos utilizando un 71% menos del agua gracias a la investigación de empresas como Jeanologia. Acabados hechos con tecnología láser o Ozono pueden contribuir para la reducción de la huella hídrica de la industria textil.

Entonces, ¿qué puedo hacer?

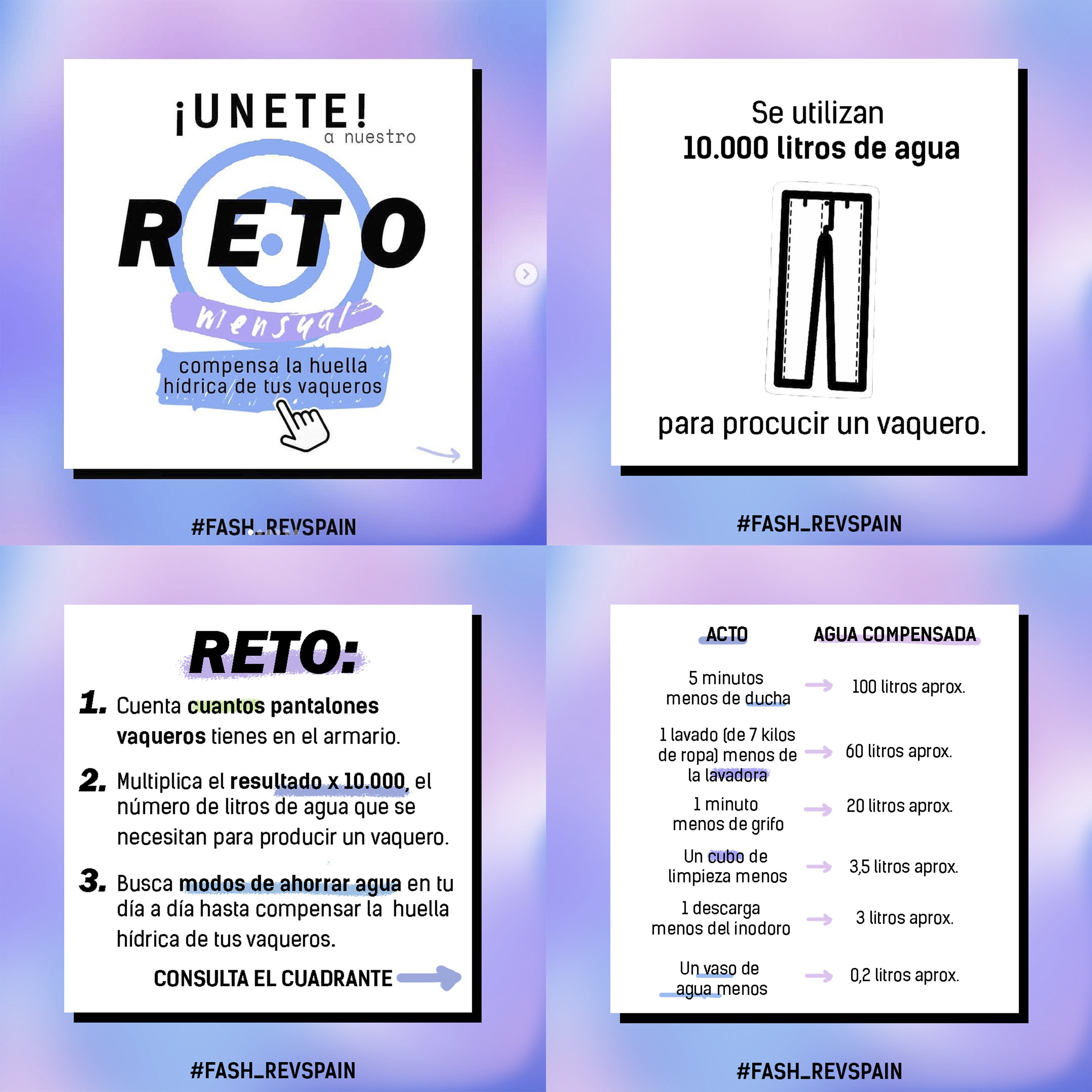

La huella hídrica de un español promedio es de 6,700 L de agua al día, el equivalente a 42 barriles llenos de agua. Eso sucede en un mundo donde al día de hoy, más de 1,000 millones de personas no tienen acceso a agua potable, mientras que 2,600 millones carecen de saneamiento adecuado. Por eso, intentar reducir nuestro impacto es un reto importante y necesario. Durante el mes de marzo, animamos a nuestros seguidores en Instagram a compensar la huella hídrica de sus vaqueros. ¿Te animas?

Acuérdate de que reducir el consumo y comprar de forma más concienciada también son acciones importantes para reducir nuestros impactos en la contaminación del agua. Todo aquello que compramos tiene una huella hídrica que es la cantidad de agua necesaria para que un producto llegue a nuestras manos. Ser conscientes de eso es fundamental para tomar decisiones que hagan de nuestro planeta un lugar más sostenible.

#QuéHayEnMisColores

También puedes unirte a nuestra campaña en redes sociales compartiendo un selfie enseñando la etiqueta de tu prenda de ropa con el cartel ¿Qué hay en mi ropa?, compartirla en las redes sociales con los hashtags #QueHayEnMisColores, #quehayenmiropa y etiquetándonos: @fash_revspain.

Parar y revertir los impactos de la contaminación del agua por tintes es un compromiso con el futuro del planeta y el bienestar de la humanidad. Nuestra contribución individual es importante, pero no debemos olvidar que el cambio de la industria textil es esencial para que podamos empezar una ruta más justa y sostenible.

1%: this equals the percentage of the 250 biggest clothing brands that publish data on the prevalence of gender-based violations in their supplier facilities. It shows the lack of support of women, especially female garment workers and women of colour, and their rights in the fashion industry. Today, on International Women’s Day, it’s time for the industry and policy makers to acknowledge this and to finally act upon it.

Gender inequalities in the fashion supply and production chains

There are approximately 40 to 60 million garment workers in the world today and millions more in other parts of the supply chain, in cotton fields and stores. The majority of those workers are women, thus representing the backbone of an industry worth almost $3 (€2.5) trillion per year today. In the majority of cases, garment workers are paid too low wages to have a decent living, they are subject to countless human rights violations and forced to work overtime in unsafe working conditions. The women behind our clothes face gender-based violence in order to survive and feed their families. Factories often deny their right to maternity leave or child care, and sexual abuse and harrassement in their workplace as well as on their way to work, is commonplace.

Gender wage gap and sticky floor

Despite women representing the majority of textile workers, gender-based wage discrimination happens on a wide scale. According to a 2019 report from the International Labour Organisation (ILO), who has investigated the garment sector in nine countries in Asia, the average raw gender pay gap is approximately 18%. Another 2019 study on garment factories in Bangladesh showed that men get more promoted than women and thus go up the ladder quicker, resulting in a gender wage gap among workers as women are stuck in entry-level positions.

Moreover, to keep prices low and be able to compete, factories often outsource their production to homeworkers, with as much as 60% of garment production done at home in Asia and Latin America. Homeworkers have even fewer rights and bargaining power than factory workers and earn very little for their work. Here again, the vast majority of homeworkers are women.

Unequal chances and glass runway

Throughout the fashion supply chain, men, despite representing a minority, tend to work in better-paid and higher-level positions such as general managers and supervisors. Men also find themselves doing higher-skilled jobs – more valued and paid for – like cutting, because they have more opportunities to learn these new skills than women.

This disparity and gender inequality do not disappear when going up the global fashion production chain, on the contrary. Despite accounting for the vast majority of fashion schools’ students, and making up more than 70% of the total workforce in the fashion industry, women hold less than 25% of leadership positions in top fashion companies. “Only 14% of major brands are run by a female executive”, according to a study by the Council of Fashion Designers of America, Glamour and McKinsey & Company, which highlights the existence of “The Glass Runway” at the top of the fashion industry pyramid.

Female leadership

Women themselves can be the basis of social change in the supply chain, whether they occupy positions at the top, in the middle or at the bottom. In leadership roles they provide better working conditions, a more positive working environment and they can be an example for future female entrepreneurs. In the middle or at the bottom of the supply chain they are indispensable to form unions, and as a result to effectively stand up for women’s and workers’ rights.

The power of collectivity for women

Trade unions are a powerful tool to ensure safer working conditions for workers, protect their rights and negotiate employee’s benefits. This collective bargaining is crucial to improve labour conditions in the garment supply chain. Despite all the challenges faced by women in the garment factories, many are organising themselves to ask for better conditions, in turn empowering other women who might be marginalised or discouraged to act for fear of retaliation in their jobs. Their collective power can help them become stronger and more independent and bring about emancipatory change. In Indonesia, for example, factory workers formed the Inter-Factory Workers’ Federation (FBLP – Federasi Buruh Lintas Pabrik) with a proportion of 90% of women in it. Within the FBLP, the Women Workers Committee fights against abuse and sexual harassment happening in garment factories in KBN Industrial Zone in Cakung. In 2017, after having collected data and spoken up to the police and the Ministry of Women Empowerment and Child Protection, the Women Workers Committee succeeded in setting up posts for complaints and advocacy for women within the factories, as well as warning signs. They are also relentlessly raising awareness and informing the workers about sexual violence and how to eliminate it, empowering the women to fight back.

The importance of entrepreneurship

Entrepreneurship is of great importance especially in the Global South, where women often live in precarious circumstances. It’s often upheld as a solution for numerous problems: it creates wealth and jobs, it offers welfare and can build confidence and status. Entrepreneurship is a mechanism for independence and female entrepreneurship is being seen as a great tool for economic empowerment which also leads to bigger social changes. In recent years, women entrepreneurship or access of women to the business world is the most rapidly growing economic phenomenon in developing nations such as Bangladesh. Investing in these women means investing in a more sustainable future, also in the fashion industry. Investments in local craftsmanship for example for fashion purposes can have a big impact on local communities, more especially for the women in those communities.

Woman at the top

Not only do women represent the people who make our clothes, they also make up the majority of the target audience of the fashion industry. This results in the fact that female leaders generally better understand workers’ and consumers’ needs and wishes than men, which could translate not only into better working conditions and flexibility, but also into more value for the customer and eventually increasing customer satisfaction.

Moreover, female leadership roles in global fashion companies lead to brands being more transparent and having better company culture and higher values. Through providing a safe, comfortable and positive working environment companies can break the stigma around sexual harassment, which is necessary because this is something women who have experienced or witnessed it are still reluctant to talk about and/or report. For the company itself, a positive working environment will of course result in more success in the long run.

Having women at the top of the fashion supply chain also communicates a strong message of independence and empowerment to the outside world. They become an example for those who dream of a job as a leader in a fashion company, which will eventually lead to the diversification of the whole sector. This in turn helps the achievement of the broader Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) set out by the United Nations, especially goal n°5: “Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls”.

So what are we waiting for?

Patriarchal societies unfortunately keep women away from their full potential. From research we know the consequences of this situation In the fashion industry: no equal pay, sexual harassment, and so on… . It gives a clear image of those things we want to get rid of so much. And it’s true, change happens slowly, but we need policy makers and brands to take their responsibility seriously. Brands need to acknowledge the power they have as a business and use it to foster positive change. They can, for example, work together with suppliers to tackle gender-related problems and they have to take responsibility for what’s happening in their supply chain. In addition, brands need to become more transparent. That way, NGO’s for example can localise problems faster. Being transparent as a brand isn’t the ultimate goal, but it’s a means to zoom in on these issues and deal with it. Finally we need support and action from policy makers. This week the European Parliament will discuss and vote (on Wednesday) on EU- corporate due diligence. This would make brands accountable for harm caused to people and planet. It could be a big (or even huge) step forward! But here too the condition remains – knowing that this will most likely be implemented by predominantly men – : also zoom in on gender equality and women’s rights.

References

Picture: Woman vector created by freepik – www.freepik.com

Brown, P., Haas, S., Marchessou, S., & Villepelet, C. (2018, October). Shattering the glass runway. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/shattering-the-glass-runway

Business of Fashion. (2015, May 3). How can fashion develop more women leaders? The Business of Fashion. https://www.businessoffashion.com/community/voices/discussions/how-can-fashion-develop-more-women-leaders

Clean Clothes Campaign. (n.d.). Gender Discrimination. https://cleanclothes.org/gender-discrimination

Debnath, G. C., Chowdhury, S., Khan, S., Farahdina, T., & Chowdhury, T. S. (Eds.). (2019). Role of women entrepreneurship on achieving sustainable development goals (SDGs) in Bangladesh (Vol. 10, Issue 5). https://cberuk.com/cdn/conference_proceedings/2020-01-05-09-32-39-AM.pdf

Emran, S. N., & Kyriacou, J. (2017). What She Makes: Power and Poverty in the Fashion Industry. https://whatshemakes.oxfam.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Living-Wage-Media-Report_WEB.pdf

Fashion Revolution. (2020, April). Fashion Transparency Index 2020. https://issuu.com/fashionrevolution/docs/fr_fashiontransparencyindex2020

Human Rights Watch. (2019, February 12). Combating Sexual Harassment in the Garment Industry. https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/02/12/combating-sexual-harassment-garment-industry

International Labour Organization. (2019). Promoting Decent Work in Garment Sector Global Supply Chains. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_protect/—protrav/—travail/documents/projectdocumentation/wcms_681644.pdfµ

Labour Behind the Label. (n.d.). Who we are. Retrieved 4 March 2021, from https://labourbehindthelabel.org/who-we-are/

Menzel, A., & Woodruff, C. (2019). Gender Wage Gaps and Worker Mobility: Evidence from the Garment Sector in Bangladesh. National Bureau of Economic Research, 1–57. https://doi.org/10.3386/w25982

Mondiaal FNV. (2017, December 18). The Day The Voices Raised [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FOMZMK-bijI

Ojediran, F., & Anderson, A. (2020). Women’s Entrepreneurship in the Global South: Empowering and Emancipating? Administrative Sciences, 10(4), 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci10040087

Parker, J. (2019, December 12). Patriarchal textile industry in Jakarta. ICL-CIT. https://www.icl-cit.org/patriarchal-textile-industry-in-jakarta/

Pathak, D. (2017, August 15). 5 Reasons why India needs more Women Entrepreneurs. YourStory.Com. https://yourstory.com/mystory/f8bbb906ca-5-reasons-why-india-ne

Pike, H. (2016, September 9). Female Fashion Designers Are Still in the Minority. The Business of Fashion. https://www.businessoffashion.com/articles/fashion-week/less-female-fashion-designers-more-male-designers

Schultze, E. (2015). Exploitation or emancipation? Women workers in the garment industry. Fashion Revolution. https://www.fashionrevolution.org/exploitation-or-emancipation-women-workers-in-the-garment-industry/

United Nations. (n.d.). Goal 5 | Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Retrieved 4 March 2021, from https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal5

WIEGO. (n.d.). Garment Workers. Retrieved 4 March 2021, from https://www.wiego.org/garment-workers

Hablemos de Fast Fashion y Salud. Si estás leyendo este artículo quizás ya estés familiarizado con los aspectos económico, medioambientales y sociales del mundo de la moda en general, y de la Fast Fashion en particular. Pero quizás no sepas que hay una faceta más, que merece la pena considerar cuando hablamos de nuestra manera de producir y consumir textiles. Me refiero al impacto directo que los textiles pueden tener sobre nuestra salud.

En Europa se utilizan alrededor de 15.000 formulaciones químicas diferentes para textiles. Para la producción de una sola prenda se pueden llegar a utilizar hasta 40 compuestos químicos diferentes (1). Estas sustancias confieren a la prenda características que la industria nos ha vendido como necesarias. Se trata de propiedades como el antiarrugas y antimanchas, que nos permiten – según la publicidad – ahorrar tiempo y dinero. Incluso, dicen, nos podrían salvar la vida, como es el caso de las telas tratadas con retardantes de llamas, que hacen que las prendas no ardan en caso de incendio.

PERO ¿CUÁL ES EL COSTE REAL QUE ESTAMOS PAGANDO?

En números: 9,3 millones de toneladas métricas de productos químicos se utilizan en la producción mundial de textiles cada año. El 25% de todas las sustancias químicas producidas a nivel mundial se emplea en la industria de la moda (1). Las implicaciones medioambientales son ingentes. Las consecuencias para los trabajadores del sector textil son incalculables tanto en término de morbilidad como de mortalidad.

¿Y CUALES SON LAS CONSECUENCIAS PARA EL CONSUMIDOR?

Cuando esa prenda, que no arde, es impermeable, de colores vivos que resisten al sol y a los lavados, acaba en nuestros armarios, se convierte en una amenaza directa para nuestra salud. Los investigadores de la Universidad de Granada en el 2019 publicaron un estudio analizando la presencia de bisfenol-A y parabenos en textiles y la correspondiente actividad hormonal derivada de la exposición dérmica a calcetines para bebés y niños de 0 a 48 meses. Los resultados fueron contundentes: “las concentraciones de bisfenol-A son alarmemente altas y la actividad hormonal es la esperada para tales concentraciones” (2).

Estas sustancias están clasificadas como disruptores endocrinos: tienen la capacidad de alterar el equilibrio hormonal de un organismo aumentando, reduciendo o bloqueando aquellos procesos fisiológicos controlados por las hormonas. Las consecuencias de una exposición prolongada a estas sustancias sintéticas incluyen: trastornos del comportamiento, pubertad precoz, obesidad, asma y cáncer de mamas entre otros.

El problema es que este aspecto no está regulado, no hay control, ni límites que respetar (3). En las etiquetas de las prendas hay muy poca información: nos indican el tipo de fibra utilizada y el lugar en que se ha producido; pero no sabemos nada de las sustancias químicas empleadas durante el proceso de producción. ¿Compraríamos una camiseta cuya etiqueta pusiera: 20% algodón, 80% poliéster + polibromados + metales pesados + ftalatos + alquifenoles?

Aunque la legislación no nos ampare todavía, tenemos que hacer un ejercicio de responsabilidad, no solo para nosotros, sino para todos aquellos que dependen de nuestras decisiones: nuestros hijos, familiares y todos aquellos trabajadores que viven rodeados de sustancias tóxicas todos los días, para que podamos ahorrarnos de planchar un pantalón.

Como declara con tajante ironía Lucy Siegle en su libro “To die for. Is fashion wearing out the world?”: para crear un armario perfecto tenemos que tener en mente que lo que no compramos es igual de importante a lo que compramos (4). Tenemos que estar dispuestos a renunciar a algo, a perder algo, para que todos podamos ganar.

ACTÚA

Si a ti te interesa el tema, te invitamos a mirar el trailer de Detox Fashion: Moda libre de tóxicos, de Greenpeace y también a sumarte a la campaña #QuéHayEnMiRopa a través de tus redes sociales.

Referencias:

- Andrew Hudson “Aiming to zero” sgs.com, 2017.

- Freire C et al. “Concentration of bisphenol A and parabens in socks for infants and young children in Spain and their hormone-like activities”. Environmental International, 2019.

- Nicolás Oles “Libérate de los tóxicos. Guía para evitar los disruptores endocrinos. RBA, 2019.

- Lucy Siegle “To die for. Is Fast Fashion wearing out the world?” Fourth Estate, 2011.

Mens verden er gået lockdown, og de fleste af os er gået i fælles isolation, fokuserer vi hos Fashion Revolution på, hvordan pandemisituationen påvirker de millioner af mennesker, som laver vores tøj. Mange butikker rundt om i verden er lukket ned og opfordrer i stedet for til at shoppe online. Denne her tid gør os usikre på den økonomiske fremtid, og derfor stimulerer det ikke ligefrem købelysten til at shoppe nyt tøj.

For os modeaktivister kan omstændigheder forhåbentlig medføre, at vores #Lovedclotheslast bevægelse, som vi har kæmpet for i flere år, kommer til at fylde mere – både nu og på den anden side af Corona-krisen. Produktionen af fast fashion har været voldsomt stigende de senere år og fortsætter kun derudaf. Der bliver produceret for 150 milliarder beklædning om året, hvilket tærer på vores klode og miljø, og tøjindustrien udleder mere CO2 end fly- og skibsindustrien tilsammen. Det kan ikke fortsætte, hvis vi skal holde os under de 2 plusgrader, som forskere verden over har bedt os om. Netop Fashion Revolution Week 2020 handler om at forlænge tøjets levetid og nedsætte hastigheden af vores modesystem. Som noget nyt spørger vi også #whatsinmyclothes? for at afdække de skadelige stoffer i vores tøj, og vi opfordrer til at gå på opdagelse i klædeskabet og finde ud af mere om de materialer, som vores tøj er lavet af. Vi fortsætter også med at spørge #whomademyclothes?, og fokuserer på lønningerne og forholdene for tekstilarbejderne. Vi opfordrer også køberne til at bruge deres økonomiske magt og stemme, til at stille brands og politikere til ansvar og forbedre arbejdsforhold og foreningsfrihed for alle mennesker, der arbejder på tværs af tøjbrands leverandørkæder. For det er netop de mennesker, der er udsat for de største konsekvenser af den uventede Covid-19 pandemikrise.

Det er almindeligt i den globale modeindustri, at tøjbrands betaler flere uger efter levering snarere end ved bestilling. Det betyder, at deres leverandører normalt betaler forud for materialerne eller fibrene, der bruges, for at brands køber af dem. Som svar på pandemien annullerer mange store brands og forhandlere ordrer og stopper betalinger for allerede bestilte varer, selv når arbejdet allerede er blevet udført. De tager intet ansvar for den eftervirkning, det har for de mennesker, der arbejder i deres forsyningskæder. Fabrikker har ikke andet valg end at ødelægge eller holde på de uønskede varer, der allerede er fremstillet, og afskedige deres arbejdere i hopetal.

På grund af coronavirus udbruddet, er der nu 1089 beklædningsfabrikker i Bangladesh, som er blevet påvirket af aflyste ordrer af en samlet en værdi af 1.5 milliarder dollars. Det fortæller en rapport fra Blomberg.

Pandemien gør, at en modeindustri, som allerede er i krise bliver ekstra udsat. Mere end 1 million beklædningsarbejdere i Bangladesh har allerede mistet deres job på grund af afbestillinger relateret til Covid-19, lyder det fra Center for Global Workers Rights.

Ifølge The AWAY Foundationer mange fabrikker i Bangladesh blevet lukket på ubestemt tid. Nogle arbejdere er blevet givet mindre end en månedsløn, som fratrædelsesgodtgørelse, og mange andre har slet ikke modtaget noget.

Nazma Aktor – Direktør for AWAY har forklaret: “at disse arbejdere ikke ved, hvordan de skal forsørge deres familie, hvordan de skal brødføde dem og betale for husleje samt andre nødvendigheder. De ved ikke engang, hvad de skal stille op, hvis de får brug for medicinsk behandling, hvis de får Coronavirus.”

Generaldirektøren for Den Internationale Arbejdsorganisation(ILO),Guy Ryder, beskriver den menneskelige dimension af pandemien som ødelæggende, og dens samlede sundhedsmæssige, sociale og økonomiske virkninger som den værste krise siden Anden Verdenskrig. Han tilføjer også, at krisen afslører den enorme mangel på anstændig arbejdskraft, som stadig hersker i 2020, og at den har vist, hvor sårbare millioner af arbejdende mennesker er, når sådan en krise rammer.

Mode bliver ikke kun skabt på fabrikker. Mode er også håndværk, kunsthåndværk og ting, der ofte bliver lavet i uformelle miljøer. I henhold til Artisan Alliance er håndværk den næststørste beskæftigelseskilde i udviklingslandene. WIEGOvurderer, at der er omkring to milliarder uformelle arbejdstagere overalt i verden, der mangler grundlæggende arbejds-, social- og sundhedsbeskyttelse. Som et resultat af COVID-19, der truer den globale handelsstrøm, står arbejderkooperativer, håndværksgrupper, lokale håndværksbaserede samfund, hjemmebaserede arbejdere, landbrugsarbejdere og landmænd over for fatale økonomiske forhold.

Fashion Revolution har altid forsøgt at være ærlige over for samfundet om de problemer, der skjuler sig i den globale modebranche. Efter at vi blev dannet som reaktion på den 3 største industrielle katastrofe i historien, nemligRana Plaza kollapset i 2013, hvor 1138 mennesker omkom og over 2000 blev hårdt såret, er vi ikke fremmede for udnyttelse og ulighed inden for branchen. Men vi har været og vil fortsat være fokuseret på løsninger og dedikeret til at finde måder at gøre en positiv forskel på. For os ligger et af svarene i vores manifest for en revolution af moden, og vi vil bruge de næste måneder (og år) på at mobilisere vores samfund til at gribe ind for at opbygge denne fremtidige mode.

Vores evne til empati styrkes af vores fælles globale erfaring, og selvom vi nu sidder indendørs, kan vi stadig bruge sociale medier til at gøre en forskel, især når vi taler sammen. Derfor beder vi vores globale samfund om at være mere aktive end nogensinde før. At spørge #WhoMadeMyClothes? og kræve, at modebrands beskytter arbejderne i deres forsyningskæde, ligesom de ville gøre med deres egne ansatte, især under denne hidtil usete globale sundheds- og økonomiske krise.

Hvis vi ikke gør noget nu, vil modebranchen vende tilbage til den sædvanlige forretningsmodel, når dette er over. Lad os i stedet antænde en revolution og opbygge et nyt system, der værdsætter menneskers og jordens velfærd frem for profit. Det betyder, at vi lige nu skal stå sammen for at beskytte og støtte de mennesker, der fremstiller vores tøj.

Det kan du gøre:

1. Send et brev til dine foretrukne modebrand og kræv, at de overholder de ordrer, de allerede har lagt hos deres leverandører, og sørg for at arbejderne, der fremstiller deres produkter, er beskyttet, understøttet og betalt korrekt under denne krise. Vi har oprettet en template på vores hjemmeside her, hvor du hurtigt og nemt kan sende en mail til de store tøjmærker som vi har listet. Mailen er skrevet du skal blot indtaste din mail og vælge det brand du vil spørge?

2. Giv penge direkte til almennyttige organisationer, der yder støtte til tøjproducenter, der har mistet deres job. Vi anbefaler at give penge til:

AWAJ Foundation– En non-profit organisation, der er grundlagt og ledet af beklædningsarbejdere i Bangladesh, der yder støtte til over 740.000 arbejdere. Dette inkluderer retshjælp, sundhedsydelser, organisation af fagforeninger, uddannelse af arbejdstagerrettigheder og industri og politik fortalervirksomhed. Donationer går direkte til arbejdstagere, der har mistet deres job. Dette vil hovedsageligt være i form af kontantudbetalinger for at sikre, at deres grundlæggende behov for mad og husly bliver opfyldt. Hvis du ønsker at yde et bidrag, så skriv til wagj@dhaka.net.

GoodWeave International– En non-profit organisation, der arbejder for at stoppe tvangsarbejde og børnearbejde i globale forsyningskæder. De har lanceret COVID-19 børne- og arbejdstagerbeskyttelsesfond for at levere øjeblikkelig humanitær hjælp og tjenester til sårbare befolkninger i Indien, Nepal og Afghanistan. de indsamler penge og betaler for levering af mad og ressourcer til arbejdstagere og deres børn. Doner her.

The World Fair Trade Organisation (WFTO)har lanceret #StayHomeLiveFair-kampagnen til støtte for sit globale netværk af arbejdere, landmænd, kunsthåndværkere og samfund under krisen. Du kan støtte ved at besøge deres webshop og støtte deres medlemmers crowdfunding-indsats. Støt her

CARE, den globale NGO for social retfærdighed, har arbejdet i beklædningsindustrien i over 20 år og fokuserer på at beskytte og støtte kvinders og pigers rettigheder og behov under pandemien. CARE’s Emergency Surge Fund matcher alle donationer og bruger midler til hurtigst muligt at give familier hygiejniske masker, håndvaskestationer og hygiejnesæt. Doner her.

3. BE CURIOUS FIND OUT DO SOMETHING

Forhold dig nysgerrigt og spørg #whomademyclothes #whatsinmyclothes

Gå på opdagelse i dit klædeskab, kig på dine labels og undersøg dine tøjbrands hjemmesider, for at se hvad de fortæller dig om, hvordan de har produceret dit tøj!

Vi opfordrer stadig til, at man forlænger levetiden af sit tøj. Ved at fordoble en t-shirts levetid har du sparet 44% CO2. Så vask på få grader, reparer dit tøj, når det går i stykker, og byt eller sælg det, når det endelig skal videre og køb genbrug. Stil krav til virksomhederne, så de gentænker deres strukturer, implementerer bæredygtige praksisser og kommer ned i hastighed. Vi opfordrer til, at man laver kærlighedshistorier på nettet om sit tøj eller en #haulternative, som betyder, at man viser frem på sine sociale medier, hvad man allerede har af tøj i sit klædeskab, og hvordan man kan style det på nye måder. Brug ekstra tid på din garderobe, kreer noget ud af tøjrester og reparer det du har, hvis det er gået i stykker.

Når du kigger efter nyt tøj så gå efter de små, bæredygtige brands. De har som regel mere kontrol med deres leverandørkæder end de store kæder, som har lange og komplicerede forsyningskæder, der er svære at gennemskue. Men hold øje med hvad brandet selv fortæller. Desuden er GOTS certifikatet et mærke, der både garanterer ordentlige miljø og sociale forhold i en produktion. Så det er også værd at kigge efter om tøjet har det mærke.

Følg vores organisation OG elsk jeres tøj meget mere.

There are three things I have been passionate about over the course of my life: sailing and the sea, the indigenous cultures of South and Central America, and creating a more sustainable fashion industry.

Working with Pachacuti, the hat brand I founded over two decades ago, and at Fashion Revolution over the past six years, has brought together the latter two areas in many ways, but now I am incredibly excited to be able to draw all three of these strands together. In February and March 2020, I will be setting sail with eXXpedition to investigate plastic pollution and toxics in our oceans. Almost 10,000 women from around the world applied to take part in the two year voyage and I feel incredibly fortunate to have been selected to crew on the leg from the Galapagos to Easter Island.

I learnt to sale on the magnificent J-Class yacht Velsheda in the late ’80s and spent a few summers as crew before jumping over to the square rigged brig TS Astrid on which I spent many happy months sailing the Channel and taking part in the Tall Ships Race. I then worked on various boats in the Caribbean for a year and sailed across the Atlantic on the tops’l schooner TS Unicorn. I remember night after night on the seemingly pristine sea watching the glowing, glittering phosphorescence resulting from the bioluminescence of organisms in the surface layers of the sea (we took two months crossing the Atlantic so there were plenty of sea sparkle nights to enjoy!) I never imagined that I would be sailing the oceans again three decades later to carry out research into the degradation of the marine environment.

My Masters in Native American Studies at the University of Essex was the culmination of an interest in the Andean region which stemmed from somewhere far back in my childhood – I remember asking for a picture book about the Incas as a Christmas present one year when I was still quite young. I immersed myself in learning about indigenous cultures past and present and would have continued with my PhD on the symbolism of colour and natural dyes in the Andes. However, having set up Pachacuti in the summer holidays and seen at first hand the real difference fair trade could make to textile-producing communities in Ecuador, I decided to turn my interest in the region to more practical use.

One of the key concepts of the Andean worldview is ayni, meaning reciprocity and balance. Balance does not mean just a static equibrium; the Inca strived for the creation of an animated cosmos through a system of continual exchange based on mutual respect, justice, and solidarity. They saw reciprocity as the foundation for peace, resilience and enduring relationships with our environment and our community both near and far. Ayni was a continuous accompaniment to life in the Andes and the foundation on which society was based. Indeed, life itself can be seen as ayni.

If the equilibrium between communities and the natural world was altered, it could result in floods, or lack of rains. Andean peoples understood that ayni has to be recreated every day in order for regeneration to take place and, as a result, knew that they needed to give things up, to make sacrifices to restore balance. Reciprocity moves people beyond self interest in order to do something for the common good.

Perhaps it is not surprising that in 2008, Ecuador became the first country to legally recognise the rights of nature and two years later Bolivia adopted the Law of the Rights of Mother Earth. This means in practice that people can now sue on behalf of the ecosystem. The Ecuadorian Constitution says this will help to “achieve the good way of living, the sumac kawsay.” Nature is part of the social fabric of life, not a resource to be exploited. The Andean concept of good living or living well doesn’t mean living better than others, nor does it imply the accumulation of material wealth. It means living well together, with nature, with mutual support, with ayni.

I was reminded of this whilst on holiday this summer, in a chalet by the sea on Branscombe beach in Devon. I was working there with my daughter, Sienna, and we were discussing stakeholders for Fashion Revolution’s policy dialogue toolkits. She told me that we must make sure we include stakeholders who don’t have a voice like the ocean and marine life. It seemed so obvious once she said it and I was astonished I had never previously thought of including them. This just emphasised to me how far we have become detached from seeing our world as a living being.

Reciprocity is inherent in the way the earth works, although there are limits that are difficult to reverse once they are crossed, as set out in the UN United in Science report issued on 22 September. Our activities, our pollution, our degradation of the marine environment are stressing the earth’s natural capacity for reciprocity. If we are to tackle toxics and plastic pollution in our oceans, as well as climate change, waste, and the myriad other environmental issues relating to the fashion industry, we know that every choice and every action matters. If we want to see regeneration of our waterways and oceans which are essential for living well on this planet together, we need to take co-operative responsibility. The resources of both land and sea are a gift, and this gift requires reciprocity in order to maintain healthy ecosystems.

When I join eXXpedition and sail some 2000 miles through the Pacific Ocean, I will be taking part in groundbreaking scientific research on board this floating laboratory to help build a comprehensive picture of the state of our seas. I will also be helping to unravel how we got into this mess and how we can help shift our mindsets towards a more sustainable, a more balanced, future which encourages progress to a more regenerative system. The worldview of the peoples who inhabit the countries past which I will be sailing may well help us to find some of these solutions.

***

The eXXpedition Round the World voyage, which sets sail from Plymouth, UK on October 8th 2019, will sail through some of the most important and diverse marine environments on the planet. This includes crossing four of the five oceanic gyres, where ocean plastic is known to accumulate, and the Arctic on board 73ft sailing vessel S.V. TravelEdge. Under the directorship of award winning ocean advocate Emily Penn, 300 women will join the research vessel as crew over 30 voyage legs to journey more than 38,000 nautical miles. Follow news and updates via #eXXpedition @exxpedition on Twitter / @exxpedition_ on Instagram /eXXpedition on Facebook

I am looking for sponsorship and donations towards my participation in this groundbreaking voyage. Please see more information here – I am very grateful for any support.

Header photo: Soraya Abdel Hadi/eXXpedition

The Environmental Audit Committee is launching an inquiry into the sustainability of the fashion industry.

The Committee will investigate the social and environmental impact of disposable ‘fast fashion’ and the wider clothing industry. The inquiry will examine the carbon, resource use and water footprint of clothing throughout its lifecycle. It will look at how clothes can be recycled, and waste and pollution reduced.

Mary Creagh MP, Chair of the Environmental Audit Committee, said:

“Fashion shouldn’t cost the earth. But the way we design, make and discard clothes has a huge environmental impact. Producing clothes requires toxic chemicals and produces climate-changing emissions. Every time we put on a wash, thousands of plastic fibres wash down the drain and into the oceans. We don’t know where or how to recycle end of life clothing.

“Our inquiry will look at how the fashion industry can remodel itself to be both thriving and sustainable.”

The growth of the fashion industry

According to a 2015 report from the British Fashion Council, the UK fashion industry contributed £28.1 billion to national GDP, compared with £21 billion in 2009.[1] The globalised market for fashion manufacturing has facilitated a “fast fashion” phenomenon; cheap clothing, with quick turnover that encourages repurchasing.

Environmental impact of clothing production

Clothing production consumes resources and contributes to climate change. The raw materials used to manufacture clothes require land and water, or extraction of fossil fuels. Clothing production involves processes which require water and energy and use chemical dyes, finishes and coatings – some of which are toxic. Carbon dioxide is emitted throughout the clothing supply chain. In 2017 a report by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation on ‘redesigning fashion’s future’ found that if the global fashion industry continues on its current growth path, it could use more than a quarter of the world’s annual carbon budget by 2050.

Environmental impact of purchase, use and disposal

Synthetic fibres used in some clothing can result in ocean pollution. Research has found that plastic microfibres in clothing are released when they are washed, and enter rivers, the ocean and the food chain.

Sustainability issues also arise when clothing is no longer wanted. A report by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation found that the growth of clothes production is linked to a decline in the number of times a garment is worn. Clothes disposed of in household recycling and sent to landfill instead of charity shops have an environmental impact, such as contributing to methane emissions. Charities have complained that second hand clothes can be exported and dumped on overseas markets. The UK Government has a commitment to ‘Sustainable Production and Consumption’ under UN Sustainable Development Goal 12.

Manufacturing in the UK

In recent years there has been a renewed interest in clothing that has been made in Britain. However there are concerns that the need for quick turn-around in the supply chain to facilitate the demand for “fast fashion” has led to poor working conditions in UK garment factories.

The Committee will also examine the sustainability of garment production in relation to the UK’s social and environmental commitments under the UN Sustainable Development Goals. The UK Government has a commitment to ensuring ‘Decent work and economic growth’ by protecting labour rights and promoting safe and secure working environments for all workers under UN Sustainable Development Goal 8.

Terms of Reference

The Committee invites submissions on some or all of the following points by 5 pm on Monday, 3rd September 2018.

Environmental impact of the fashion industry

- Have UK clothing purchasing habits changed in recent years?

- What is the environmental impact of the fashion supply chain? How has this changed over time?

- What incentives have led to the rise of “fast fashion” in the UK and what incentives could be put in place to make fashion more sustainable?

- Is “fast fashion” unsustainable?

- What industry initiatives exist to minimise the environmental impact of the fashion industry?

- How could the carbon emissions and water demand from the fashion industry be reduced?

Waste from fashion

- What typically happens to unwanted and unwearable clothing in the UK? How can this clothing be managed in a more environmentally friendly way?

- How much unwanted clothing is landfilled or incinerated in the UK each year?

- Does labelling inform consumers about how to donate or recycle clothing to minimise environmental impact, including what to do with damaged clothing?

- What actions have been taken by the fashion industry, the Government and local authorities to increase reuse and recycling of clothing?

- How could consumers be encouraged to buy fewer clothes, reuse clothes and think about how best to dispose of clothes when they are no longer wanted?

Sustainable Garment Manufacturing in the UK

- How has the domestic clothing manufacturing industry changed over time? How is it set to develop in the future?

- How are Government and trade envoys ensuring they meet their commitments under SDG 8 to “protect workers’ rights” and “ensure safe working environments” within the garment manufacturing industry? What more could they do? Are there any industry standards or certifications in place to guarantee sustainable manufacturing of clothing to consumers?

Deadline for submissions

Written evidence should be submitted through the inquiry page by 5 pm on Monday, 3rd September 2018. The word limit is 3,000 words. Later submissions will be accepted, but may be too late to inform the first oral evidence hearing. Please send written submissions using the form on the inquiry page.

Diversity

The Committee values diversity and seek to ensure this where possible. We encourage members of underrepresented groups to submit written evidence. We aim to have diverse panels of Select Committee witnesses and ask organisations to bear this in mind if asked to appear.

Further information

- Guidance: written submissions (including information on data protection)

- About Parliament: Select committees

- Visiting Parliament: Watch committees

Membership of the Committee:

http://www.parliament.uk/business/

committees/committees-a-z/commons-select/environmental-audit-committee/membership/

Media Information: Sean Kinsey kinseys@parliament.uk/ 07917 488791

Specific Committee Information: eacom@parliament.uk/ 020 7219 6150

Committee news and reports, Bills, Library research material and much more can be found at www.parliament.uk. All proceedings can be viewed live and on-demand at www.parliamentlive.tv

Photo credits:

Houses of Parliament and Garment Factory in Bangladesh by Carry Somers

Ocean by Ross Miller

by Carry Somers and Orsola de Castro

On 8 May 2013, the two of us wrote an email which began ‘like many, we have seen the terrible tragedy in Bangladesh as a call to arms and feel that we should build on the momentum which has been generated. An annual Fashion Revolution Day would be a way to ensure that these deaths are not in vain, show the world that change is possible, and celebrate those involved in creating a more sustainable future for fashion’.

The responses to our request for involvement fell into two quite clear camps. Many responded with no hesitation; one email we received back just said yes, yes, yes! Some expressed a degree of hesitancy. Do we really want to call for a revolution in the fashion industry? How about calling it Fashion Evolution? Although the two of us are very different in very many ways, we are remarkably similar in others: we are both entrepreneurs, both pioneers in our respective fashion spheres, both risk-takers and both have a fundamental belief in the power of people to effect change given the right motivation. We had no doubt that a revolution was needed – a radical and pervasive transformation of the way in which the fashion industry operates.

We were right to push for revolutionary change. People were ready to listen.

Looking back at the minutes from our very first meeting, we had real clarity around how we would communicate our message in order to accelerate change: we need one big aim; make it as visible as possible; keep it strong; make it positive without ignoring the negatives; make it inclusive; talk about how the relationship with the people who make our clothes has broken down and connections need to be reestablished. Finally, we needed to give people a question they can all ask: who made my clothes?

This clarity of vision, coupled with the right channels of communication, has made Fashion Revolution the biggest fashion activism movement in the world. We have teams in over 100 countries and there are well over 1000 events happening all around the world this week.

Fashion Revolution is first and foremost about people; it is about making visible the connections between everyone in the fashion supply chain as a first step towards change. We’ve made citizens realise that their own wardrobe is in the fashion supply chain, about three-quarters of the way between the cotton seed and recycling the fibres. Everything we do has an impact on that supply chain. We reshape the fashion industry, the lives of its workers and its resources, every time we buy or dispose of an item of clothing.

Fashion Revolution was set up for the love of people, in memory of those who died at Rana Plaza, those who have died in countless other fires and building collapses in garment factories around the world, and those who are still losing their lives every week so we can wear beautiful clothes. That love of people continues to shine through. We are not about celebrities. We are not about power and success. We are about humanity. Fashion is about instant gratification. We are about the long term gratification that comes from knowing entire workshops, factories and communities are slowly becoming visible. We see empowerment not as a celebrity wearing a feminist slogan T-shirt on instagram, but as the workers who made that T-shirt being given a voice through the garment worker diaries project. When we inaugurated a new hashtag #Imadeyourclothes in 2016, someone commented on social media that it represented ‘the most joy I’ve ever had from a hashtag!’

We’ve given everyone tools to take part – there are online packs for brands and retailers, producers, makers and factories and educators. For fashion-lovers, as well as a Get Involved pack, there is our How to be a Fashion Revolutionary booklet, our fanzines Money Fashion Power and Loved Clothes Last, our guides to the #Haulternative and Love Story challenges. There are endless ways in which everyone can take part from changing your attitude, to changing your wardrobe, to changing your world. We’ve encouraged millions of people to Be Curious, Find Out, and Do Something. We don’t have all the answers. We want to encourage everyone to ask questions of their favourite brands, to do their own research, to use their power as consumers to hold the industry to account for its actions and impacts.

We’ve given everyone tools to take part – there are online packs for brands and retailers, producers, makers and factories and educators. For fashion-lovers, as well as a Get Involved pack, there is our How to be a Fashion Revolutionary booklet, our fanzines Money Fashion Power and Loved Clothes Last, our guides to the #Haulternative and Love Story challenges. There are endless ways in which everyone can take part from changing your attitude, to changing your wardrobe, to changing your world. We’ve encouraged millions of people to Be Curious, Find Out, and Do Something. We don’t have all the answers. We want to encourage everyone to ask questions of their favourite brands, to do their own research, to use their power as consumers to hold the industry to account for its actions and impacts.

We called for a revolution at the right time as the infrastructure of the industry, and the industry itself, have shifted in the past five years. We were right to call for a revolution because both ideas and practices had to be refashioned, a new paradigm was needed, and we can see this starting to happen. A revolution means change and change represents freedom. There is excitement around this change; it no longer feels dull nor scary, but represents a creative space in which to operate. Everyone within this space at this time can be considered a pioneer, and pioneers don’t have references – they make their own.

Five years on, a Fashion Revolution is taking place. Not fast enough, not enough engagement throughout the industry, but make no mistake it is happening. It’s bubbling up through the cracks and crevices, it can no longer be submerged. In another five years it will be a raging torrent, reshaping everything in its path. If you aren’t part of this movement, you will be swept along by it (or perhaps even swept away by it) as the structure of the fashion industry is revealed and revolutionised.

We are Fashion Revolution. Join us.

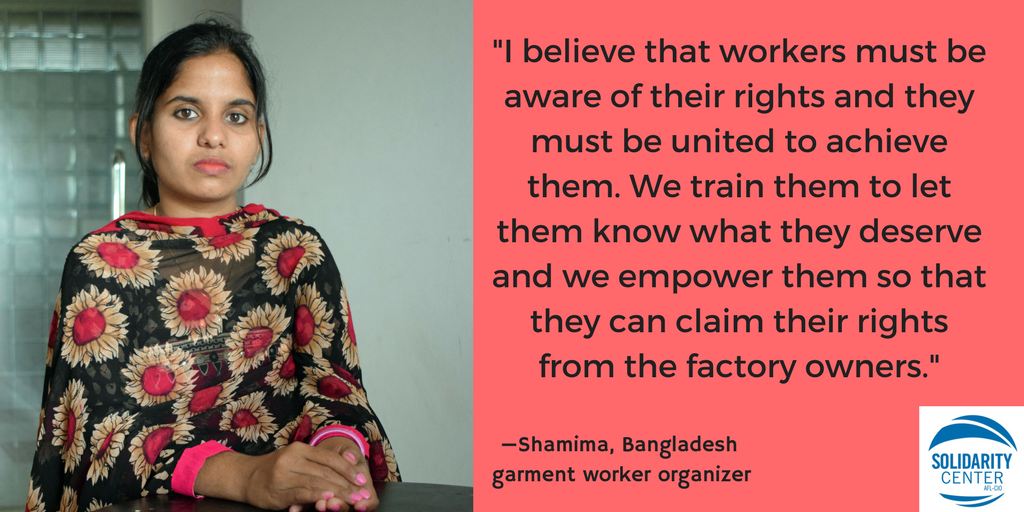

Five years after the deadly Rana Plaza building collapse in Bangladesh, workers and union activists say despite the massive demand from workers for union representation to achieve safe workplaces, worker-organizers must face down threats, harassment and violence to educate workers about their rights on the job.

Since the April 24, 2013, tragedy in which more than 1,130 garment workers died and thousands were injured, the government has approved a little more than half of the garment unions that have applied for official registration, according to Solidarity Center data. Confronted with employers and a government hostile to worker organizations, worker-organizers have sometimes risked their lives to help workers improve wages and working conditions.

Shamima Aktar, a garment factory worker and organizer with Bangladesh Garment and Industrial Workers’ Federation (BGIWF), is one of them. During a meeting with management at a newly unionized factory, managers refused to grant a demand made by the factory union that salaries be paid on a timely basis. Instead, Shamima and the other union representatives were locked in the building and beaten, she says.

“But what moved me was that hearing about our abuse, 17 trade unions around the community immediately came to our aid and barricaded the whole factory which we were in. The workers needed us on their side to be able to live in peace and I wish to [keep organizing] no matter how difficult it is for me,” she says.

Through persistence and courage in the face of daunting odds, worker-organizers have helped garment workers form unions despite the severe obstacles. In Bangladesh, more than 200,000 garment workers at 445 factories are represented by unions that protect their rights on the job.

“I have worked day and night, went to gates of factories to talk to the workers, walked with them to their homes to earn their trust and to make them aware of how they are being exploited and deprived of their rights,” says Monira Akter, an organizer with the Bangladesh Independent Garment Workers Union Federation (BIGUF). “So far, we have united 2,250 workers into trade unions, and they say that we give them courage and hope. For me, these words are enough to encourage me to work on for them.”

Abdul Hashem – father of worker killed at Rana Plaza

Poverty Wages, Safety Improvements

Wages in Bangladesh are the lowest among major garment-manufacturing nations, even though the cost of living in Dhaka is equivalent to that of Luxembourg and Montreal. The country’s labor law falls far short of international standards, and the Bangladesh government has failed to enact meaningful legal reforms, including addressing the arbitrary union registration process that is vulnerable to employer manipulation. Without a union, garment workers often are harassed or fired when they ask their employer to fix workplace safety and health conditions.

But due to international action after the Rana Plaza disaster, which occurred months after a deadly fire at Tazreen Fashions Ltd. factory killed 112 mostly female garment workers, a variety of efforts to prevent unnecessary deaths and injuries due to fire or structural failures—including the Bangladesh Accord on Building and Fire Safety—have remedied dangers at more than 1,600 factories.

Abul Hashem – father of worker killed at Rana Plaza

The Solidarity Center has trained more than 6,000 union leaders and workers in fire safety, helping to empower factory-floor–level workers to monitor for hazardous working conditions and demand safety violations be corrected.

Such international attention has opened up space for workers to collectively demand—and win—improvements on the job, says Monira.

“I am proud that we have been able to create leaders among the workers by organizing them into trade unions. In the past this would have been close to impossible.”

Iztiak, an intern in the Solidarity Center Bangladesh office, interviewed the worker-organizers in Dh

This week we are celebrating Fashion Revolution and the journeys of two women and acknowledge the barriers they have overcome. Nobody tells it better than the weavers themselves – they’re the true beating hearts of The Basket Room and the story behind each woven basket we sell. So we caught up with two members of the Kenyan weaving cooperative we work with: Peninah and Florence. Here’s what these talented craftswomen have to say about being working women in 2017, and the barriers they have overcome through basket weaving and working within a cooperative.

Peninah Munyao was born in 1978. She is married and has three sons aged 16, 11 and 4. As a housewife, she manages the household and also dabbles in farming and of course, basket weaving. Like so many of the weavers we work with, Peninah was taught to weave by her grandmother.

Florence Bernard is treasurer of the weaving cooperative Peninah works for, and was born in 1962. With five children aged between 38 and 23, Florence also runs a greengrocers’ as well as weaving baskets and travelling frequently to Nairobi to sell baskets. Florence has been weaving baskets since 2001 and was taught the craft as a child, by her mother.

What do you feel you have achieved as a working woman?

PENINAH: From basket weaving, I am able to meet the needs of my household: paying school fees, putting food on the table and buying clothes and other essentials, as well as having some money left over to save.

FLORENCE: I have been able to support my greengrocery and basket trading businesses from the money I make from basket weaving. I also use this income to support the needs of my family.

What challenges do you face as a working woman?

PENINAH: Sometimes it is difficult to source enough sisal fibre, since the plant is grown in a different region and it can take a while to arrive at our markets. Since I am also a mother and a housewife, my duties – primarily, taking care of my family – have to take precedence over weaving, which means that sometimes I cannot produce as many woven baskets as I would like to.

FLORENCE: Rain, although a massive blessing to farmers and food sellers, impedes basket weaving. When it does rain, weaving must stop so that the crops can be tended to. Likewise, drought also hinders basket production because again weaving must stop so that we can travel further afield than normal to find water.

Has work given you more independence?

PENINAH: Yes! Before I joined our weaving cooperative a few years ago, I used to rely on my husband for everything we needed at home. Back then, I felt I couldn’t even ask him for money for a new pair of shoes because there were just too many more important things for the home that we needed first. But when I started weaving with our cooperative, I had the means to not only help support the family, but also to surprise my husband with new things for him, like a new hat or a pair of trousers.

FLORENCE: I never travelled much before, but since we started selling the baskets in Nairobi, I’ve realised how much I enjoy travelling. I am now able to travel all over Kenya with my work, and sometimes I take my family with me. I also don’t have to rely solely on my husband’s income in running my household anymore.

Do you feel successful being part of a growing weaving cooperative?

PENINAH: Yes, I do! Not only because this is the best way to trade with buyers, but also because of the togetherness that comes from doing something you love with friends and people who can relate to and understand what you are going through.

FLORENCE: Yes. We usually contribute part of the sales of our baskets to our cooperative. These contributions have made it possible for us to purchase a piece of land where we intend to construct rental properties or a community centre. Group members can also take out loans from the savings we have.

Thank you to Peninah and Florence for sharing their stories with us. Peninah and Florence belong to the Kenyan weaving cooperatives that produce our popular Linear Fusion range of woven baskets and shoppers.