Fashion Revolution cada día, y en particular durante el mes de abril, nos invita a preguntamos #QuienHizoMiRopa? La respuesta parece obvia, pero no siempre está a la vista de todas y todos.

Detrás de cada prenda hay una persona, y cada persona detrás de una máquina de coser tiene una historia. Como equipo Fashion Revolution Chile creemos que es crucial reconocer la realidad de quienes diseñan, confeccionan, reutilizan y arreglan una prenda. Esas personas son la base del sistema que nos viste, y parte importante de la solución hacia un consumo más ético y responsable de la moda.

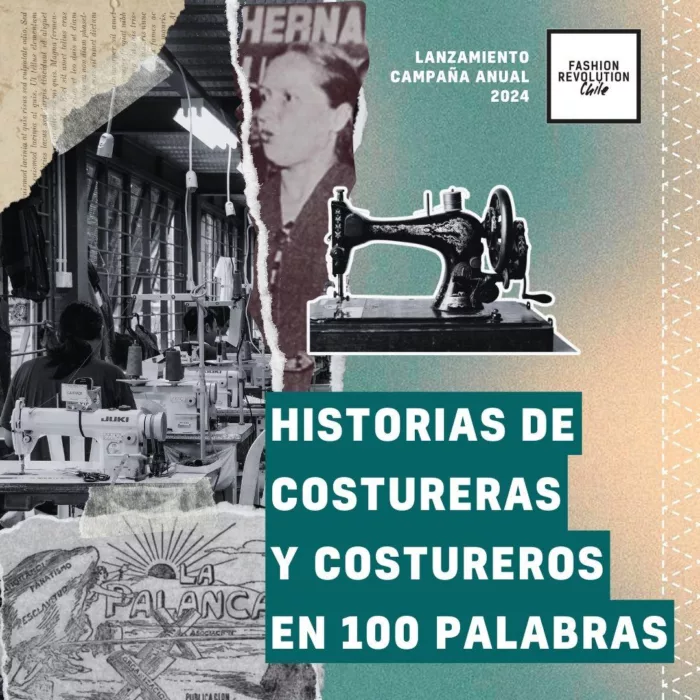

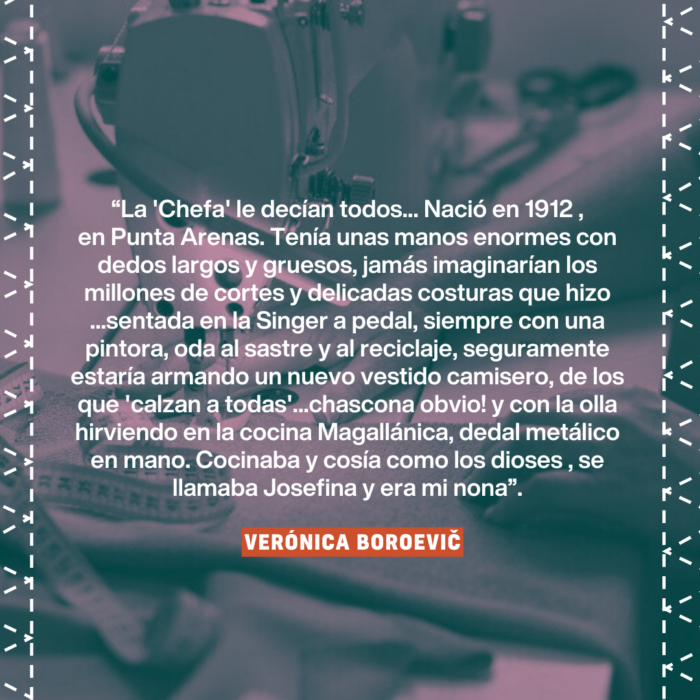

Nuestra campaña territorial 2024 “Historias de costureras y costureros en 100 palabras” nace con la intención de recoger esos testimonios, y así visibilizar la realidad a menudo olvidada de las costureras y costureros que trabajan incansablemente en la industria textil y de la moda en Chile.

Para eso, formulamos la difusión de la campaña y abrimos una convocatoria de libre participación desde el 28 de marzo hasta el 18 de abril. La que fue difundida principalmente a través de nuestras redes sociales y recibió un total de 46 historias.

Sólo en 100 palabras…

Puede ser difícil resumir la experiencia de la costura en tan poco texto, pero fueron suficientes para que algunas personas contaran cuentos, experiencias y relatos totalmente emocionantes. Algunos de ellos, entramados a una larga historia familiar, la herencia histórica del oficio y el esfuerzo que esconde el trabajo detrás de #QuienHizoTuRopa

Al finalizar la campaña, realizamos una selección de historias para exhibir en nuestro evento presencial de la Fashion Revolution Week, el día 20 de abril. Oportunidad donde nos reunimos para dialogar sobre la importancia de trabajar por una industria de la moda más sostenible, territorial y responsable, y donde también los asistentes pudieron disfrutar de seis diversos talleres, tres conversatorios, una exposición de diseño y una jornada de networking.

¡Muchas gracias a todos quienes participaron y contaron su historia!

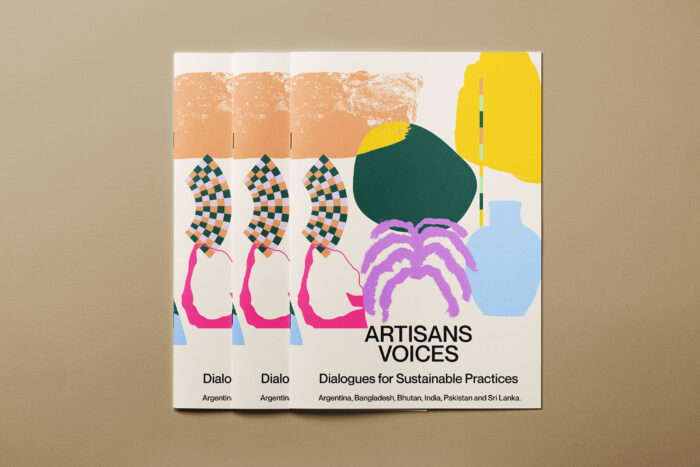

El 15 de octubre “Voces de la Artesanía: Diálogos para prácticas sustentables” se presentó en el festival de diseño TRImarchi ante un auditorio de más de 6.000 personas. Este libro es parte de Crafting Futures – el programa global del British Council – y fue desarrollado por REDIT – Red Federal Interuniversitaria de Diseño de Indumentaria y Textil (Argentina), Craft Revival Trust (India) y el British Council.

El conversatorio reunió a las protagonistas de “Voces de la artesanía” con Fashion Revolution (UK) para reflexionar en torno a las buenas prácticas necesarias en el ecosistema del trabajo colaborativo entre artesanato y diseño. Participaron: Carry Somers, co fundadora de Fashion Revolution, las artesanas argentinas Celeste Valero (Tejedores Andinos) y Anabel del Valle Luna (Thañí/Viene del monte), Sol Marinucci (Crafting Futures Argentina), el realizador audiovisual Hernán Kacew y la diseñadora Sofía Noceti.

Fashion Revolution, que comparte la cruzada por la transparencia en el universo de la moda, el diseño y la artesanía, sumó sus plataformas de comunicación como apoyo estratégico a esta iniciativa. En el marco de la última Fashion Revolution Week, en abril de 2022, se realizó un encuentro virtual organizado por Crafting Futures, British Council, REDIT y Craft Revival Trust que puede verse aquí.

Las participantes fueron Carry Somers, co fundadora de Fashion Revolution, las artesanas argentinas Celeste Valero (Tejedores Andinos) y Claudia Aybar (Randeras de El Cercado), Sol Marinucci (Crafting Futures Argentina), Ritu Sethi (Craft Revival Trust) y Alejandra Mizrahi (REDIT).

PASAJES DEL CONVERSATORIO en TRImarchi

Sol Marinucci

Diseñadora, productora cultural y coordinadora externa del programa Crafting Futures en Argentina.

“Reconociendo a las maestras artesanas como fuentes de sabiduría viva queremos sembrar conciencia sobre lo importante que es generar espacios donde explorar posibles futuros sustentables. Esta publicación busca amplificar las voces de artesanos y artesanas, por eso decidimos que los conceptos abordados fueran enunciados por quienes llevan adelante la praxis, más allá del significado etimológico o las definiciones de la academia. Quiero compartir una frase de una de las artesanas participantes, Margarita Ramírez, de la cooperativa Tinku Kamayu (Santa María, Catamarca). Sus palabras sintetizan muy bien el puente que intentó ser este libro:

‘Sentí que no estamos solas y que la gente de los saberes – como la llamo yo – de escuelas y universidades nos tomaron en cuenta. Sentí que se hacía justicia porque también nosotras, que no estudiamos, somos parte de ese mundo ya que tenemos los saberes en nuestras almas. Siento que se movió una gran piedra y que ya empezó a rodar.’

Es muy común que los saberes estén asociados a conocimientos teóricos, pero hay otro conocimiento que proviene de la práctica del hacer y de la experiencia; eso quisimos destacar. De la publicación participaron seis países ( Argentina, Bangladesh, Bután,India, Pakistán y Sri Lanka) y, en todos ellos, se repite el pedido de los artesanos por un trato justo. Nos encantaría que esto se transforme en un movimiento lleno de compromiso y acciones concretas que nos lleven a relaciones éticas, sustentables y beneficiosas.”

Celeste Valero

Artesana textil y miembro del colectivo Tejedores Andinos perteneciente al pueblo Kolla de Jujuy, Argentina. Su misión es preservar, compartir y perfeccionar técnicas textiles mediante encuentros que promueven el intercambio de saberes.

“Soy del pueblo Kolla y vivo en la quebrada de Humahuaca. Estoy aquí en representación de mi pueblo y de los más de 570 artesanos que fueron parte de este proyecto que es un sueño palpable. Para nosotros, la palabra reconocer significa mirar más allá de lo que los ojos ven. Junto a mi familia y a otros miembros de mi comunidad fundamos Tejedores Andinos bajo el lema: el alma de los textiles son sus tejedores. Realizamos técnicas textiles en diferentes telares en fibras naturales de llama y de oveja. Así ha sido por generaciones. Una de las técnicas que está a punto de desaparecer es el telar de cintura, una práctica precolombina que aún prevalece en mi familia y que habla de nuestra identidad, de nuestra cultura. Está relacionada incluso con la medicina y con la tierra. Me he puesto al servicio de mi comunidad para preservarla como heredera de este conocimiento, por eso cuento sobre ella y también la practico.

Este libro es un paso más en el camino de la preservación, la tradición y el reconocimiento. Tal vez, a partir de él las personas ajenas a la comunidad se interesen y quieran saber cómo nosotros vemos el mundo. Quizás, los inspire nuestra forma de relacionarnos como humanos y con la naturaleza. Estoy muy agradecida de estar aquí.”

Anabel del Valle Luna

Miembro de Thañí/Viene del monte, un colectivo de mujeres indígenas del pueblo Wichí reunidas para comercializar sus textiles artesanales confeccionados en fibra de chaguar. La comunidad vive en Salta, en la cuenca del río Pilcomayo, donde se unen Argentina, Paraguay y Bolivia.

“Estoy muy contenta de ser parte de esta aventura. Yo vengo del monte y para mí todo esto es muy nuevo. Nos alegra mostrar lo que hacemos, lo que somos. Quiero compartir con ustedes un texto que escribimos las mujeres del pueblo Wichí de Thañí/Viene del monte:

Creemos que para entendernos con las personas de las ciudades y quienes no son del pueblo Wichí necesitamos más comunicación. Nosotras tenemos que aprender cómo decir, cómo vender, cómo es la vida en otros lugares. Ustedes tienen que aprender de nosotras, de nuestra forma de vivir y de nuestra historia. Somos gente que vive con el monte, entendemos mensajes que traen los vientos y los pájaros, pero hay palabras en español que nos cuesta entender. Nosotras pensamos y soñamos en idioma wichí. Cuando sentimos que somos escuchadas nos volvemos de los encuentros llenas de alegría y con mucha fuerza para seguir defendiendo nuestro trabajo que es nuestra identidad, una identidad que va cambiando porque está viva.”

Carry Somers

Diseñadora, emprendedora social, activista y cofundadora de Fashion Revolution.

“Cuando el edificio Rana Plaza se derrumbó en Bangladesh, supe de inmediato que la causa fue la falta de transparencia en la industria y eso me inspiró a fundar este movimiento. Nueve años después de aquel colapso, la dignidad humana y los salarios dignos en la moda siguen cuestionados y el medio ambiente sigue sufriendo como resultado de la forma en que se fabrica y se consume la moda. La industria es vista como una campeona de la creatividad. Sin embargo, lleva más de treinta años obsesionada con la velocidad y el volumen, mientras que las artesanías lentas y antiguas, con sus rasgos individuales, son cada vez más infravaloradas.

En 2017 creamos el Manifiesto de Fashion Revolution. Uno de sus puntos habla sobre la relación entre la artesanía y la moda. Al igual que Voces de la Artesanía, es nuestra declaración de los principios sobre los que la industria debe operar. Uno de los puntos establece que la moda respeta la cultura y el patrimonio. Fomenta, celebra y recompensa habilidades y destrezas. Reconoce la creatividad como su bien más valioso. La moda nunca se apropia sin dar el debido crédito. La moda honra a sus artesanos.

La transparencia es un primer paso esencial si queremos apoyar a los artesanos y garantizar que las tradiciones textiles sigan siendo una forma de transmitir conocimientos y habilidades de madres a hijas. Tradición es una palabra viva para prácticas vivas. Una nueva tradición puede comenzar hoy. Como dijo una vez el compositor clásico Gustav Mahler, “la tradición no es el culto a las cenizas, sino la preservación del fuego”. Y al final, ese es el objetivo de este libro. La preservación del fuego que da vida y sentido a comunidades enteras.”

Acerca de “Voces de la Artesanía: Diálogos para prácticas sustentables”

El trabajo en colaboración entre comunidades artesanas y otras disciplinas suele ser un escenario desafiante. Con el fin de explorar posibles futuros sostenibles en estos cruces, el libro reúne a profesionales de la artesanía, el diseño y organizaciones de Argentina, Bangladesh, Bután, India, Pakistán y Sri Lanka. El diálogo resultante subraya los valores universales inherentes a los procesos interculturales beneficiosos para todas las partes. Los y las artesanas mantienen vivo el conocimiento y aseguran su salvaguarda al transmitirlo de una generación a otra. Escuchar y responder a sus voces se traduce en riqueza cultural y el desarrollo de vínculos más saludables.

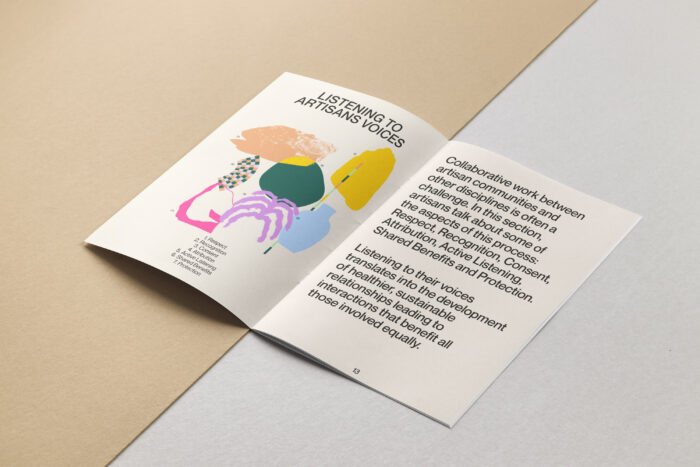

“Voces de la Artesanía: Diálogos para prácticas sustentables” está organizado en dos secciones. La primera se refiere a las prácticas éticas indispensables para la relación entre el artesanato y el mundo en general: Respeto, Reconocimiento, Consentimiento, Atribución, Beneficios Compartidos, Protección y Escucha Activa. La segunda sección destaca algunos aspectos del ecosistema artesanal que repercuten en sus prácticas: Instituciones Culturales, Transmisión y Educación, Turismo, Tecnología y Cocreación.

El libro partió de una investigación que en la Argentina se llevó adelante entre los años 2019 y 2021. La encuesta, que recogió las experiencias y los puntos de vista de quienes conforman la trama de los procesos conjuntos de creación e intercambio de conocimiento, alcanzó a más de 570 personas. Este estudio fue ideado en asociación con Rachel Kelly

(Manchester School of Art) y REDIT, con el asesoramiento del Craft Revival Trust de la India. La información recopilada y la metodología de trabajo pueden consultarse en el reporte titulado “Crafting Futures : Exploración del ecosistema artesanal en Argentina”. En el transcurso del año 2021, la investigación se amplió al sur de Asia gracias al alcance mundial del programa Crafting Futures del British Council.

Acerca de Crafting Futures

Programa global del British Council que celebra el valor de la artesanía en nuestra historia, la cultura y el mundo actual. Se basa en el intercambio y la experimentación, respetando y preservando el patrimonio tradicional.

El British Council es la organización internacional del Reino Unido para las relaciones culturales y las oportunidades educativas. Favorecemos el conocimiento y el entendimiento entre los habitantes del Reino Unido y de otros países. Esto redunda en beneficio de todos, ya que transformamos las vidas de los ciudadanos creando oportunidades, estableciendo vínculos y generando confianza mutua.

—

Lee el libro en ingles

Lee el libro en español

Last month, Artisan Voices: Dialogues for sustainable practices was presented at the TRImarchi design festival for an audience of more than 6,000 people. This book is part of Crafting Futures – the British Council global programme – and was developed by REDIT – Red Federal Interuniversitaria de Diseño de Indumentaria y Textil (Argentina), Craft Revival Trust (India) and the British Council.

The conversation brought together the protagonists of “Artisan Voices” along with Fashion Revolution to reflect on the good practices necessary in the ecosystem of collaborative work between craft and design. Participants included Carry Somers, co-founder of Fashion Revolution, Argentine artisans Celeste Valero (Andean Weavers) and Anabel del Valle Luna (Thañí/Viene del monte), Sol Marinucci (Crafting Futures Argentina), audiovisual producer Hernán Kacew and designer Sofía Noceti.

Fashion Revolution, which shares the quest for transparency in the world of fashion, design and craft, added its communication platforms as strategic support to this initiative. Within the framework of Fashion Revolution Week 2022, a virtual meeting was held, organized by Crafting Futures, the British Council, REDIT and the Craft Revival Trust, which can be seen here. The participants were Carry Somers, co-founder of Fashion Revolution, Argentine artisans Celeste Valero (Andean Weavers) and Claudia Aybar (Randeras de El Cercado), Sol Marinucci (Crafting Futures Argentina), Ritu Sethi (Craft Revival Trust) and Alejandra Mizrahi ( REDIT).

Snippets from the conversation at TRImarchi

Sol Marinucci, coordinator of Crafting Futures en Argentina.

“Recognizing the master craftswomen as sources of living wisdom, we want to raise awareness about how important it is to create spaces to explore possible sustainable futures. This publication seeks to amplify the voices of craftsmen and craftswomen, which is why we decided that the concepts addressed should be enunciated by those who carry out the praxis, beyond the etymological meaning or the definitions of the academy. I want to share a phrase from one of the participating artisans, Margarita Ramírez, from the Tinku Kamayu cooperative (Santa María, Catamarca). Her words sum up very well the bridge that this book sought to be: ‘I felt that we are not alone and that the knowledgeable people – as I call them – from schools and universities took us into account. I felt that justice was done because we, who do not study, are also part of that world since we have the knowledge in our souls. I feel like a big stone was set in motion and that it has already started to roll.’

It is very common for knowledge to be associated with theoretical knowledge, but there is other knowledge that comes from the practice of doing and experience; That’s what we wanted to highlight. Six countries participated in the publication (Argentina, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka) and, in all of them, the artisans’ request for fair treatment is repeated. We would love for this to become a movement full of commitment and concrete actions that lead us to ethical, sustainable and beneficial relationships.”

Anabel del Valle Luna

Member of Thañí/Viene del monte, a group of indigenous women from the Wichí people gathered to sell their handcrafted textiles made from chaguar fiber. The community lives in Salta, in the Pilcomayo river basin, where Argentina, Paraguay and Bolivia meet.

“I am very happy to be part of this adventure. I come from the mountains and for me all this is very new. We are happy to show what we do, what we are. I want to share with you a text that we women of the Wichí people of Thañí/Comes from the mountain wrote:

We believe that in order to understand each other with people from the cities and those who are not from the Wichí people, we need more communication. We have to learn how to say, how to sell, what life is like in other places. You have to learn from us, of our way of life and of our history. We are people who live with the mountains, we understand messages that the winds and birds bring, but there are words in Spanish that are difficult for us to understand. We think and dream in the Wichí language. When we feel that we are heard, we return from the meetings full of joy and with great strength to continue defending our work, which is our identity, an identity that is changing because it is alive.”

Celeste Valero

Textile artisan and member of the collective Tejedores Andinos belonging to the Kolla people of Jujuy, Argentina. Its mission is to preserve, share and perfect textile techniques through meetings that promote the exchange of knowledge.

“I am from the Kolla people and I live in the Quebrada de Humahuaca. I am here on behalf of my people and the more than 570 artisans who were part of this project, which is a palpable dream. For us, the word recognize means to look beyond what the eyes see. Together with my family and other members of my community, we founded Tejedores Andinos under the motto: the soul of textiles is its weavers. We carry out textile techniques in different looms in natural llama and sheep fibers. It has been this way for generations. One of the techniques that is about to disappear is the backstrap loom, a pre-Columbian practice that still prevails in my family and that speaks of our identity, of our culture. It is even related to medicine and the earth. I have put myself at the service of my community to preserve it as heir to this knowledge, that is why I communicate it and I also practice it.

This book is one more step on the path of preservation, tradition and recognition. Perhaps, based on it, people outside the community will be interested and want to know how we see the world. Perhaps they are inspired by our way of relating as humans and with nature. I am very grateful to be here.”

Carry Somers, co-founder of Fashion Revolution.

“When the Rana Plaza building collapsed in Bangladesh, I immediately knew that the cause was a lack of transparency in the industry and that inspired me to found this movement. Nine years after that collapse, human dignity and living wages in fashion remain in question and the environment continues to suffer as a result of the way fashion is made and consumed. The industry is seen as a champion of creativity. However, it has been obsessed with speed and volume for more than thirty years, while slow and ancient crafts, with their individual traits, are increasingly undervalued.

In 2017 we created the Fashion Revolution Manifesto. One of its points talks about the relationship between crafts and fashion. Like Artisan Voices, it is our declaration of the principles on which the industry must operate. One of the points states that fashion respects culture and heritage, encourages, celebrates and rewards abilities and skills, and recognizes creativity as your most valuable asset. Fashion is never appropriated without giving due credit. Fashion honors its artisans.

Transparency is an essential first step if we want to support artisans and ensure that textile traditions remain a way of passing on knowledge and skills from mother to daughter. Tradition is a living word for living practices. A new tradition can start today. As the classical composer Gustav Mahler once said, “tradition is not the worship of ashes, but the preservation of fire.” And in the end, that is the goal of this book. The preservation of the fire that gives life and meaning to entire communities.”

About the Artisan Voices project

Collaborative work between artisan communities and other disciplines is often a challenging terrain. In order to explore possible sustainable futures at these crossroads, the book brings together craft and design professionals and organizations from Argentina, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. The resulting dialogue underlines the universal values inherent in intercultural processes beneficial to all parties. The artisans keep knowledge alive and ensure its safeguard by transmitting it from one generation to another. Listening and responding to their voices translates into cultural richness and the development of healthier bonds. “Artisan Voices: Dialogues for Sustainable Practices” is organized into two sections. The first refers to the ethical practices essential for the relationship between the craftsmanship and the world in general: Respect, Recognition, Consent, Attribution, Shared Benefits, Protection and Active Listening. The second section highlights some aspects of the craft ecosystem that have an impact on its practices: Cultural Institutions, Transmission and Education, Tourism, Technology and Co-creation.

The book was based on an investigation that was carried out in Argentina between 2019 and 2021. The survey, which collected the experiences and points of view of those who make up the plot of the joint processes of creation and exchange of knowledge, reached more than 570 people. This study was conceived in association with Rachel Kelly (Manchester School of Art) and REDIT, with the advice of the Craft Revival Trust of India. The information collected and the work methodology can be consulted in the report entitled “Crafting Futures: Exploration of the craft ecosystem in Argentina”. Over the course of 2021, the research expanded to South Asia thanks to the global reach of the British Council’s Crafting Futures programme, a project which celebrates the value of crafts in our history, culture and today’s world. It is based on exchange and experimentation, respecting and preserving traditional heritage.

Read the book in English

Read the book in Spanish

Artículo redactado por Nora Sesmero Andrés, voluntaria de Fashion Revolution.

Humana Fundación Pueblo para Pueblo es una organización sin ánimo de lucro que se encarga del reciclaje del textil en España. Los ciudadanos españoles nos desprendemos al año de 1’2 millones de toneladas de ropa, y eso tiene un gran impacto en el medioambiente.

Si por algo destaca Humana es por ser una organización transparente. En su web podemos encontrar toda la información trazada para que el ciudadano de a pie conozca cómo trabajan.

Esta fundación se dedica a reinsertar en el ciclo de vida las prendas de las que los consumidores nos desprendemos, aunque no dan abasto. De las 1’2 millones de toneladas de prendas que los ciudadanos españoles desechan al año, actualmente solo se recicla un 10%. Otros proyectos en España como Moda re- se dedican también a esta labor.

Humana tiene 5200 contenedores de donación de ropa repartidos por España, promoviendo que los consumidores donemos nuestra ropa cuando creamos que realmente ya no la podemos vestir, aprovechando todo su potencial. En sus plantas de reciclaje de Madrid y Barcelona, donde se puede acudir para conocer cómo trabajan, se observan pilas y pilas de sacas de ropa prensada. Algunas de esas sacas pesan alrededor de unos 400kg.

Cuando los ciudadanos dejan sus bolsas de ropa en los contenedores de Humana, estas se transportan a sus plantas de reciclaje y mediante un proceso rápido y efectivo se clasifican según su estado para dotarlas de un nuevo uso. Un 90% de estas son destinadas a la venta de segunda mano tanto en España como en los países donde realizan sus programas sociales.

De esta manera, tratan de fomentar la moda de segunda mano, a partir de la venta de ropa en sus tiendas, donde según muchos de sus clientes, podemos encontrar prendas completamente nuevas. Esto demuestra la mala educación que tiene el consumidor de moda a día de hoy. Por ello, creen que es importante educar a este en la sensibilización, que seamos conscientes del impacto que tienen nuestras compras. “Dado que las calidades de la moda rápida son pésimas, las prendas que se reciclan también son cada vez de peor calidad”, afirma el responsable de comunicación de Humana, Rubén González. La solución pasaría por dejar de consumir este tipo de moda y comenzar a invertir en prendas de calidad.

Parte de los beneficios que esta fundación produce se destinan a realizar proyectos sociales en países del sur, relacionados con la educación, la salud, la agricultura, el cambio climático, el desarrollo comunitario, etc. En países como China, Ecuador, Laos, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Senegal, Zambia y España. En 2020, sus proyectos de cooperación involucraron a cerca de 125.000 personas.

Algunos de los proyectos de educación se encargan de formar a profesores de primaria en el entorno rural, ya que defienden que los profesores bien formados, motivados y comprometidos son la mejor palanca para hacer avanzar la educación. Impulsan la agricultura urbana, ecológica y sostenible, además del desarrollo rural. En el ámbito de la salud, tratan de educar a las personas para prevenir el VIH. En 2021 se ha profundizado en el fortalecimiento de los programas relacionados con cambio climático y del trabajo junto a socios especializados. Esta labor contra las consecuencias del calentamiento global tuvo su prolongación en la COP26 de Glasgow, en la que Humana participó para compartir la experiencia acumulada mediante los programas Farmers Club, establecer lazos con otras entidades y detectar oportunidades para seguir promoviendo acciones en favor de la adaptación y la mitigación de las consecuencias del cambio climático.

Humana ha convertido un oficio antiguo, el de los traperos, en una manera de hacer que la moda sea circular y financiar con ello distintos proyectos sociales.

A partir de 2025, el reciclaje de ropa será obligatorio en la Unión Europea. Esto produce una sensación de esperanza, ya que será menos probable que encontremos imágenes como la del mercado de Kantamanto, en Ghana. Es importante poner el foco en lo que aún queda por mejorar, y la reducción de la producción y el consumo son claves para hacer que la industria de la moda de un salto hacia la sostenibilidad.

Otra de las tareas pendientes consiste en que las prendas que se produzcan sean de un solo material. Debido a que reciclar ropa de diferentes composiciones es un trabajo complejo y caro.

La organización trabaja en el fortalecimiento de iniciativas de I+D+i para prolongar el ciclo de vida del textil y el calzado y, al mismo tiempo, multiplicar sus posibilidades de reaprovechamiento, en el marco de la economía circular y la jerarquía de residuos. Por ello, más allá de la preparación para la reutilización, la Fundación colabora en España con diferentes asociados en el impulso de proyectos de diversa naturaleza, desarrollando de modo conjunto soluciones concretas en aras de impulsar una mayor circularidad en la gestión del textil usado. Como su participación como miembros impulsores del Pacte per a la Moda Circular de Cataluña o su reciente adhesión al Consejo Asesor del proyecto Life Kanna Green, nacido para proponer y definir un nuevo modelo de consumo y economía circular para el calzado, basado en los principios del ‘Cradle to cradle’, donde nada es un residuo.

Otros de los objetivos de Humana son: conseguir abarcar más cantidad de ropa para poder reciclarla, optimizar sus procesos de reciclaje, ampliar el número de tiendas, generar empleo, avanzar con sus proyectos sociales, trabajar con otras empresas del sector de la reutilización, ayuntamientos, etc. Su mensaje es positivo, creen que vamos hacia una moda sostenible, mucho más regulada e inteligente.

Si quieres leer el anterior artículo de la autora, pulsa aquí.

Egy magyar sportruházati márka, amely odafigyel a környezetbarát anyaghasználatra és etikus körülmények között gyártat, itthon – a FANNA Polewear alapítójával, Nagy Fannyval beszélgettünk többek között a rúdtáncról, a fenntarthatóságról és a társadalmi szerepvállalásról.

A rúdtánc mint sport egyre nagyobb népszerűségnek örvend hazánkban is. Milyen indíttatásból döntöttél egy sportruházati márka alapítása mellett?

Korábban tervezőként tevékenykedtem, kicsit más területen. Bőrkiegészítőket és -ruhákat terveztem, és már akkor szempont volt a környezettudatos tervezés és gyártás, így újrahasznosított bőrökkel dolgoztam. Időközben elkezdtem a rúdsportot űzni, és azonnal beleszerettem. Onnantól egyértelmű volt, hogy a korábbi irányt fogom kiegészíteni egy vegán és környezettudatos sportruházati vonallal. Az alapinspiráció abszolút a rúdtánc volt, viszont nyitottak vagyunk szinte minden más sportra, illetve utcai vagy otthoni darabokat is készítünk.

Miben nyilvánul meg a fenntarthatóság a márka életében?

Amiben csak lehet! Kezdve az anyagválasztástól, annak a felhasználási módjától, a csomagoláson át a szállításig. Hitelesített anyagokkal dolgozunk, gyűjtjük a használt ruhákat, melyekből ajándéktáskát készítünk a vásárlóinknak. Emellett az újrahasznosított csomagolás nagyszerű módja a már használt anyagok élettartamának a meghosszabbításának!

Kérlek, mesélj részletesebben az általatok használt környezetbarát anyagokról!

Hosszútávú célunk, hogy szélesebb körben is hozzájárulhassunk a fenntarthatósághoz, aminek alappillérjét a megfelelő anyagválasztás képezi. Kétfajta anyaggal dolgozunk jelenleg: az ECONYL® és az OEKO-TEX® minősítésű biopamuttal. A tanúsítvány megszerzéséhez többek között etikus dolgozói körülmények szükségesek, amit a márkánk 100%-ban támogat. Ezt az anyagot továbbá kevesebb vízfelhasználással és vegyszermentesen állítják elő, ami az egészségünk számára is kiemelten fontos.

Az ECONYL® anyagot szintetikus hulladékokból, az óceánból származó halászhálókból állítják elő, majd az újrahasznosítást követően pontosan ugyanolyan minőségű nylonfonalat kaphatunk, mint amilyen a szűz nejlon. Az egyik legjobb tulajdonsága, hogy számtalanszor újrahasznosítható. Az ECONYL® fonalból készült újrahasznosított poliamid tökéletes fürdőruhához és edzőfelszereléshez, míg a biopamutból póló, body, valamint szabadidő ruházat készül.

Mire kell ügyelni a rúdtánc öltözékek tervezésénél?

Arra kell csak figyelni, hogy a hajlatok lehetőleg szabadon maradjanak, ezért található a kollekciókban olyan hosszú ujjú felső vagy nadrág is, amin az érintett részek szabadon vannak. Ettől függetlenül vannak olyan elemek ebben a sportban, amiket leggings-ben is meg lehet csinálni.

Egy erős közösség alakult ki az évek során a brand körül, milyennek látod a Fanna-nőket?

Nagyon jóleső érzés, hogy ilyet visszahallhatok. Imádom a Fanna nőket, mindenki csodálatos, igazi tudatos vásárlók, tele szeretettel! Nekem ők adják a legnagyobb motivációt. A Fanna-nők számomra igazi szuperhősnők.

Örömmel láttam, hogy a FANNA Polewear kiáll a fontos, társadalmi ügyek mellett és ez anyagi támogatásban is megnyilvánul. Milyen szervezeteket választottatok eddig és miért éppen azokat?

Szeretnénk minél több szektort támogatni, mert annyi fontos és fejlesztendő terület van a világban. Eddig támogattuk a Jövő Öko-Nemzedéke Alapítványt, akik Magyarországon tevékenykednek a környezetvédelem ügyében, többek között az illegális szemetelés ellen. Továbbá, a Szívemben Született Afrika egyesületet, ők Afrikában edukálnak és segítik többek között az ott élő nőket, a menstruációs szegénységben szenvedőket. Ezt szerettük volna mi is támogatni – személyes ügyemnek tekintem a nők támogatását.

A Szivárványcsaládokért Alapítványt is támogattuk, mert hiszünk az elfogadásban, a szeretetben és az egyenlőségben. Fontosnak éreztem, hogy kiálljunk egy ilyen ügy mellett is, és mondjuk el a véleményünket egy közösségként, mert összefogással és egymás támogatásával érhetünk el változásokat. Hisszük, hogy a szerelem mindenkié.

Jelenleg a 10 millió Fa Alapítvánnyal dolgozunk együtt. Ebben már aktívabban is szeretnénk részt venni, ezért létrejött a FANNA 10 millió fa közösség, ahol már mi is szervezhetünk faültetést, ezúton is minden segítő kezet szeretettel várunk eseményeinken!

Idén ti is csatlakoztatok a Who made your clothes?-kampányhoz, miért tartottátok ezt fontosnak?

Sajnos még mindig sokan nem néznek a márkák mögé, hogy az adott termék valójában hogyan, milyen körülmények között készült és mégis hogyan lehet ennyire olcsó? Illetve nagyon nehéz lekövetni, és átlátni egy nagy céget, hogy hogyan dolgoztat, milyen kondíciókat biztosít. Nekünk nagyon fontos, hogy megmutassuk és kommunikáljunk arról, hogy mi hogyan dolgozunk.

Kiemelt jelentőségű és égetően sürgős, hogy a rabszolgamunka felszámolódjon. Talán kicsit felfoghatatlan számunkra, hogy ez létezik. Itthon is több olyan varroda van, ahol konkrétan addig dolgoznak a varrónők a varrodában, ameddig élnek, mert soha nem voltak bejelentve, ezáltal nincs nyugdíjuk, illetve 300-500 forintot kapnak egy ruhadarabért, amiből – mikor én odakerültem – kettőt tudtam megvarrni egy egész nap alatt.

Persze, a tapasztalt varrónők többet is el tudnak készíteni. A fizetésük úgy sem volt az egekben, de legalább egészséges körülmények között dolgoztak. Én tanulni és tapasztalatot gyűjteni mentem oda elsősorban, viszont érthető, hogy nem is tudják megtartani a fiatal munkaerőt ezekkel a feltételekkel. Szóval nekem ez is egy személyes ügy. Egyrészt, mert tapasztaltam is a helyzetet, másrészt, mert ez is főleg a nőket érinti. Számomra nagyon fontos, hogy ne csak a vásárlóinknak adjuk meg a tőlünk telhető legtöbbet, hanem a legnagyobb szupererőnknek, a munkatársainknak és a gyártóinknak is biztosítsuk azt, amitől nekik is megéri ezt a munkát szeretettel és lelkesen végezni.

Mit üzennél az olvasóknak, hogyan váljanak tudatos vásárlóvá?

Először is ne vásároljunk, csak akkor, ha valamire tényleg szükségünk van. Ha eldöntöttük, hogy valamire szükségünk van, akkor informálódjunk az adott márkáról. Ez azért nehéz 2021-ben, mert a legtöbb márka bevette a „programjába” valamilyen szinten a fenntartható szemléletet, a kérdés csak az, hogy kik azok, akik nem a greenwashing stratégiát űzik. Kövessetek tudatos influencereket, akik már alaposan utánanéztek azoknak a márkáknak, akiket ajánlanak. Példul Mengyán Esztert, akinek van egy szuper oldala is, ahol gyűjti a hasonló szellemű tudatos márkákat, és kifejezetten a divat területre koncentrál. Minden egyéb tippekért pedig Vászonzsákoslány néven futó Antal Évinek és Zsebibogyó Zsófinak vannak remek tartalmai a témában.

Szerző: Pölz Klaudia, fotók: Fotók: Matovic Mana

Will cultural appropriation in the fashion industry ever end? How can artisans protect their traditional cultural expressions? Is it possible for designers to work in an ethical way with Indigenous communities? These are the questions that a groundbreaking new digital database aims to challenge by protecting the culturally significant designs of ethnic groups from misappropriation and misuse.

Back in 2019, MaxMara was found selling clothing decorated with patterns that looked identical to the traditional embroidery and appliqué designs of the Oma people. The Oma are an ethnic minority group of about 2,800 people living in the remote mountains of northern Laos, recognised in the region for their hand-spun, indigo-dyed clothing decorated with vibrant red embroidery and appliqué.

Unlike the authentic Oma designs, the MaxMara replica patterns were printed on the fabric, not hand-embroidered or hand sewn. In addition, there was no garment label acknowledging the textile designs as belonging to the Oma, generating a risk of cultural dilution of Oma intangible cultural heritage.

When informed of the situation, the Oma people of Nanam Village confirmed that they had no knowledge of the use of their designs and motifs by the fashion company and that they were not requested permission for digitising the designs for production and sale. They were surprised to see their traditional textile designs reproduced with machines by people outside of the Oma community, and commercialised without their consent and without any compensation.

In response to the social media campaign and international press, MaxMara responded with demands to remove the posts they qualified as defamatory and damaging to the reputation of the company, and threatened to take legal action in the event of non-compliance. They also asserted that the allegedly copied design was elaborated in an original way, and inspiration was taken from the pattern of a vintage fabric which the company considered as being in the public domain.

As a result, Cultural Intellectual Property Rights Initiative® (CIPRI), Traditional Arts and Ethnology Centre (TAEC) and the Oma of Nanam Village in Laos have developed a new digital database that documents a multitude of traditional garments, motifs and techniques that are culturally significant to the Oma in various ways. The ‘Documenting Traditional Cultural Expressions: Building a Model for Legal Protection Against Misappropriation and Misuse with the Oma Ethnic Group of Laos‘ report details the purpose and process of creating this database, its legal framework, and the impact on the community.

The Oma Traditional Textile Design Database© now serves as a tool for asserting cultural intellectual property rights for the Oma people of Nanam Village in Laos, and as a legally defensive tool to protect against the unconsented use of the Oma’s Traditional Cultural Expressions (TCEs). Additionally, the Database is a means to document TCEs for the community at large to ensure cultural continuity, and provide a rich source of research to facilitate collaboration between Oma artisans and fashion and textile companies.

Most importantly, the model of the Database can be licensed, royalty-free, by any other Indigenous group, ethnic group or local community that wants to develop cultural intellectual property protection. This opens new doors to respectful collaboration between brands and Indigenous communities, providing hope for a fashion future without commercialised cultural appropriation.

Here, we talk to CIPRI founder Monica Boța-Moisin to find out more about the journey of developing this unique project, its implications for the legal governance of fashion design, and why cultural sustainability matters.

How does this project put the theory of protecting cultural expressions into practice in a tangible way?

The database has multiple functions – on one hand, it is proof of this custodianship relationship, in the absence of a globally applicable legal framework to protect Traditional Cultural Expressions. It’s a public forum through which the community can prove they are custodians of this knowledge. Another important feature of the database is that you can learn about the Oma and the frameworks that they would ideally collaborate in. However, part of the database is private and you cannot get access to the content unless you initiate this discussion and you get the prior consent of the Oma.

With this database, we are also challenging the myth that the public domain is something that we can all take from and do whatever we want with. We haven’t yet changed international law with this database. It’s not like from now on Traditional Cultural Expressions are no longer in the public domain, but it is a step in the right direction. This is a debate that has to begin, and then laws will follow and misconceptions will change.

We have to look back at where the system came from. And at the time when we started speaking about intellectual property rights, nobody could have probably ever imagined that we would get to this paradox where corporations that are protected through IP tools, like trademarks, like industrial design, like patents, then put this trademark on someone else’s identity. Because it’s not just a matter of intellectual property. It’s a matter of commercialising someone’s identity.

In developing the database, what were the biggest challenges you came across and how did you overcome them?

Well, it’s been a complex process that requires funding and takes a lot of time and cross-disciplinary expertise. Going through the process with a community was pioneering in itself. There are certain collections of knowledge in parts of the world, but to go and create a traditional textile design database is something that we took the first steps in.

We had to be very careful every step of the way because every action has a consequence. The process of Free Prior Informed Consent, explaining what are the consequences of digitising this kind of knowledge, we thought of all possibilities and the measures that we have to take to prevent the negative consequences from happening. The work of TAEC was essential for the success of this endeavour. There is a need for on-the-ground experience and understanding of the local handicraft ecosystem, anthropological and ethnographic studies in the area. And then the legal theory on top. So it’s a very complex, time-consuming, resourceful process. And it needs much more support for the model to be replicated by communities across the globe.

Could you explain why The 3Cs’ Rule of Consent. Credit. Compensation© matters for the fashion industry to collaborate respectfully with artisans and Indigenous communities?

It is my life’s mission to work to build bridges between the fashion industry and Indigenous communities, ethnic groups and local communities. So it’s sometimes difficult to even pinpoint why I find this important because I feel any kind of exploitative behaviour should not be part of how we live. The most amazing things happen when we learn to value and appreciate knowledge. And this also means the knowledge of parts of the population that we are not used to seeing as business partners. It is a change to reimagine collaborative models and there’s a lot of opportunity there for both to grow.

I believe in knowledge exchange and knowledge partnership, and I think we cannot speak about fairness, equity and good working conditions when we exploit anyone’s time and knowledge. We know so well that different forms of exploitation are still part of how the fashion industry works. For example, how many people haven’t been equitably compensated for their internships in the industry? So it’s important to be clear, transparent to ask for Free Prior Informed Consent, and to communicate what you want to do with this knowledge. What do you want to do with this collection? What implications can it have on the community? If it booms, could you continue to produce at scale or can you licence the designs? Or would the community be okay with seeing digital prints of these designs?

Obviously, there are many elements of financial sustainability that need to be taken into consideration in a collaboration like this too. But that doesn’t mean that the fashion company is always the one that can dictate the rules. So this communication and this partnership are vital. People who are engaging in these conversations often want to solve someone else’s problems, instead of giving them the tools to do it themselves or recognising their value. Because I think a lot of these problems that we try to solve from top-down could be solved at ground level. If communities would be remunerated or part of an ecosystem that values what they know to do best, they would have more time and resources to have access to education. They wouldn’t live in poverty if they would be paid for the time and knowledge of their handcrafted work.

A lot of people in the world still refer to handcrafted production as a cottage industry, it’s basically working from home. So we’re all a cottage based economy now in the pandemic. If we change this behaviour, the concept of exploitation of humans by humans, if we can eradicate that, we will solve so many of the endemic problems like poverty, discrimination and lack of access to education.

Why is it important to encourage and enable collaboration in this way, rather than simply to condemn cultural appropriation altogether?

I’ve always been an advocate for finding a way to work together. Ideally, there would be by now a focus in companies to have a department that tackles these issues. At the Cultural Intellectual Property Rights Initiative®, we have the expertise to educate fashion brands on how to create internal policies to avoid cultural appropriation and focus on cultural sustainability.

But it’s also important to keep having these cultural exchanges and creating. So it’s not about not getting inspiration from traditional textiles, it’s about building together. And to do that there needs to be alignment between words and actions. You cannot have a fashion company that has culturally appropriated and then look at their CSR policies and see that one of their aims is to alleviate poverty. It just doesn’t make sense. It doesn’t align. So once we formulate the good intentions we have to think about where to direct them.

The database has legal protection behind it and is the beginning of a much bigger, potentially worldwide replicable model. Ultimately it also symbolises that we are ready and open to work together with fashion brands and find constructive solutions.

For a designer or brand who wants to collaborate with producers of traditional textiles such as the Oma people, how would they go about this?

Reach out! We are now looking for the first fashion collaborators for the Oma. If brands want to work together, they would have to enter the database, write to an email address there that links to the Traditional Arts and Ethnology Centre, then we will have joint discussions and shape this collaboration together. Myself and TAEC have been empowered by the Oma of Nanam Village to represent them legally, so there’s this kind of multi-party representation at the moment.

At the Cultural Intellectual Property Rights Initiative®, we are assisting both fashion companies and local communities and we can intermediate this process. For this, the experience of doing fieldwork in India has been extremely valuable. And I think all the lawyers that work in this space need to have some direct interaction with communities to be able to immerse in that cultural context and understand the complex dynamics in these communities as well. We have these kinds of tough conversations with everyone who approaches us, irrespective of their role. And I think the landscape of how these collaborations are forming is a very interesting space, where we feel our work is valuable.

You use the hashtag #NotPublicDomain to discuss this work, but why is that Traditional Cultural Expressions should not be in the public domain?

The idea of something being in the public domain means, on the one hand, that it’s not protected by copyright or IP tools in general, and that it can therefore be used and exploited without the need to ask for consent. There is inequality by default that these expressions are not protectable under the conventional IP system, despite certain specific customary laws applying to them. This automatically leaves them in the public domain, which makes them automatically vulnerable to use without consent.

The conventional and existing IP system doesn’t protect this type of work, but it doesn’t mean that you should be exploiting it however you want because the community has certain rules, and this is where the customary laws come into play. These communities never signed an agreement saying we abide by the International IP rules. The IP system, like anything in this world, is an invention – we all decided, when you create something, we’ll call you the author. And because you’re the author, we will give you some money for it. And you have the right to be named the author, and you also have the right to decide how your work is being exploited commercially, whether your work can be translated into a different language, etc. That’s something that you can decide. These mechanisms do not exist yet in the space of Traditional Knowledge and Traditional Cultural Expressions.

I always say the limits of the public domain are being challenged because these communities finally have a chance to explain their position, they want to be involved in the process of decision making of what happens to their intangible patrimony and their heritage. And they should have the right to do that. So we can now invent a system that also takes their interest and their particular works into account.

What are the implications of this project for other Indigenous communities, ethnic groups and artisans beyond the Oma in Laos?

The great outcome of this project is that a template of the database is available for free for anyone who wants to work on a similar endeavour. TAEC and CIPRI are committed to supporting any community that reaches out to us and says they want to go through the same process.

How does this project align with the UN Sustainable Development Goals and why was this important to include?

Because there’s so much talk from corporations and industry stakeholders on working towards achieving the goals by 2030. But I think people fail to see how much cultural sustainability has to play in the sustainability narrative, and how cultural sustainability is actually embedded in the Sustainable Development Goals. In my workshops, I work specifically with 8 of the 17 goals that expressly refer to cultural sustainability, but nobody communicates that as a pillar in itself, so how are we gonna achieve the goals by 2030?

So with this project having such a strong cultural sustainability component, it was important that we show how the project aligns with the Sustainable Development Goals. And obviously, these communities have so much knowledge of how to maintain biodiversity and natural rhythms in the region where they are, so that contributes to environmental sustainability. Everything is so connected.

Finally, what does cultural sustainability mean to you?

We can look at the culturally embedded values and practices that have been maintained in a society from generation to generation, because of their positive outcomes. To exemplify, we can look at the principle of design to minimise waste, this has always been embedded in how all ethnic groups, local communities and Indigenous people have created their traditional garments.

Like in Romania with hemp fibre, it took so much time to spin that yarn and weave that cloth, so you don’t want to waste it. It just wasn’t part of the design thinking because they weren’t creating for consumption, they were creating for wellbeing. So cultural sustainability is about ecosystemic thinking. And that’s why it should be the basis of all sustainability actions.

Further reading and watching

Securing Cultural Intellectual Property Rights For The Oma People Of Nanam Village In Laos

Traditional Arts and Ethnology Centre: Intellectual Property Rights for Traditional Artisans in Laos

This is a guest blog by the team behind the Garment Worker Diaries, an initiative from Microfinance Opportunities and SANEM that collects regular, credible data on the work hours, income, expenses, and financial tool use of workers in the global apparel and textile supply chain. The objective of the ongoing project is to help inform government policy decisions, collective bargaining, and factory and brand initiatives related to improving the lives of garment workers.

In this blog post, we meet Shila, a garment worker in Bangladesh, to discover how socioeconomic inequality is leaving women and children at disproportionate risk from the impacts of climate change.

View this post on Instagram

Shila was forced to leave her home when sea level rise contributed to its destruction. Her parents were unable to afford to continue paying for her education, so she became the caretaker of another family’s baby. Eventually, Shila found her way to Dhaka. She believes she was born sometime in the autumn of 1986, and she’s been a garment worker since 2000.

Shila is one of the 1,300 workers participating in the Garment Worker Diaries study, which has been conducting interviews with workers continually for the past 34 months, once per week, 52 weeks per year. Some respondents drop out of the study, others remain with us for a long time –Shila has been part of the study since June 2018. In late December 2020, she sat down with our film crew to discuss her life story, her daily routine, her work, and her aspirations for both herself and her son.

Shila’s story is at times tragic, mundane and uplifting. It’s unique, and we encourage you to watch the entire interview. But, there are other garment workers in much the same position as Shila. More specifically, there are many other female garment workers who have had and will have experiences similar to Shila’s—at the intersection of climate change, gender inequality, and the gruelling economics of global supply chains.

Like Shila, nearly 90% of the garment workers in Bangladesh migrate from somewhere else. Female garment workers are slightly more likely to migrate than male garment workers. While the majority of both women and men migrate for reasons related to economic hardship, men are slightly more likely than women to report that they migrated for reasons related to economic opportunity or because they prefer city-style living (as opposed to life in the villages). Women, on the other hand, are slightly more likely than men to say they were forced to migrate, and they are much more likely than men to report that they migrated to get married or to follow their spouse or another family member. We know this because in August 2020 we interviewed the workers participating in the GWD study about their migration experience.

View this post on Instagram

Also like Shila, workers are aware of the impact of climate change and the local effects of air pollution. A majority, 62%, answered “Yes” to the question “Are you concerned about climate change?” Here are a few of the reasons why, in their own words:

“People are being affected with various diseases and there are more storms and tidal surges due to climate change.” – Female worker, age 23, working in the garment industry for 3.5 years.

“People are being harmed economically. Crops are being damaged as there is no rain at the time when it is supposed to rain.” – Male security guard, age 50, working in the garment industry for 4 months.

“Black smoke emitted from cars, factories, and brick kilns is polluting the environment and people are getting sick from it. Medical treatment is very expensive. I fear that if this continues, it will be difficult for people to live a healthy life.” – Female machine operator, age 30, working in the garment industry for 12 years.”

The workers’ answers are consistent with what other data tell us: Bangladesh is consistently ranked as one of the most at-risk countries for weather-related events. Numerous advocacy groups, non-governmental organizations, academic journals and media outlets have been and will continue to call attention to the particular risk that Bangladesh faces.

But the workers are not well-equipped to deal with the consequences of climate change, and women workers, like Shila, are especially vulnerable. They have already migrated to improve their standard of living, but their earnings do not give them the financial cushion they may need to cope with the disruptions brought by climate change. For example, during the 12-month period from April 2020 to March 2021, the typical salary earned by female garment workers in Bangladesh was about Tk. 8,300, while the typical salary earned by male garment workers was about Tk. 10,100 (about USD $117/EUR €96/GBP £83).

If we look at the typical monthly work hours for female and male garment workers for that same time period, we see that women typically worked about 198 hours per month while men typically worked about 214 hours per month. This means on the whole that women earn about Tk. 42/hour to men’s Tk. 47/hour. Another way to put it is men earn about 12% more than women.

Shila, and workers like her, work long hours to make ends meet for wages that provide little buffer against the potential economic disruption of climate change. It is clear that human rights and the environment are deeply connected; the women who make our clothes and the children they raise could be disproportionately affected by the negative impacts of climate change. Watch the video below to learn more:

Further reading

International Women’s Day: Women’s rights and the environment in fashion

Fashion Revolution Podcast: Garment Worker Diaries

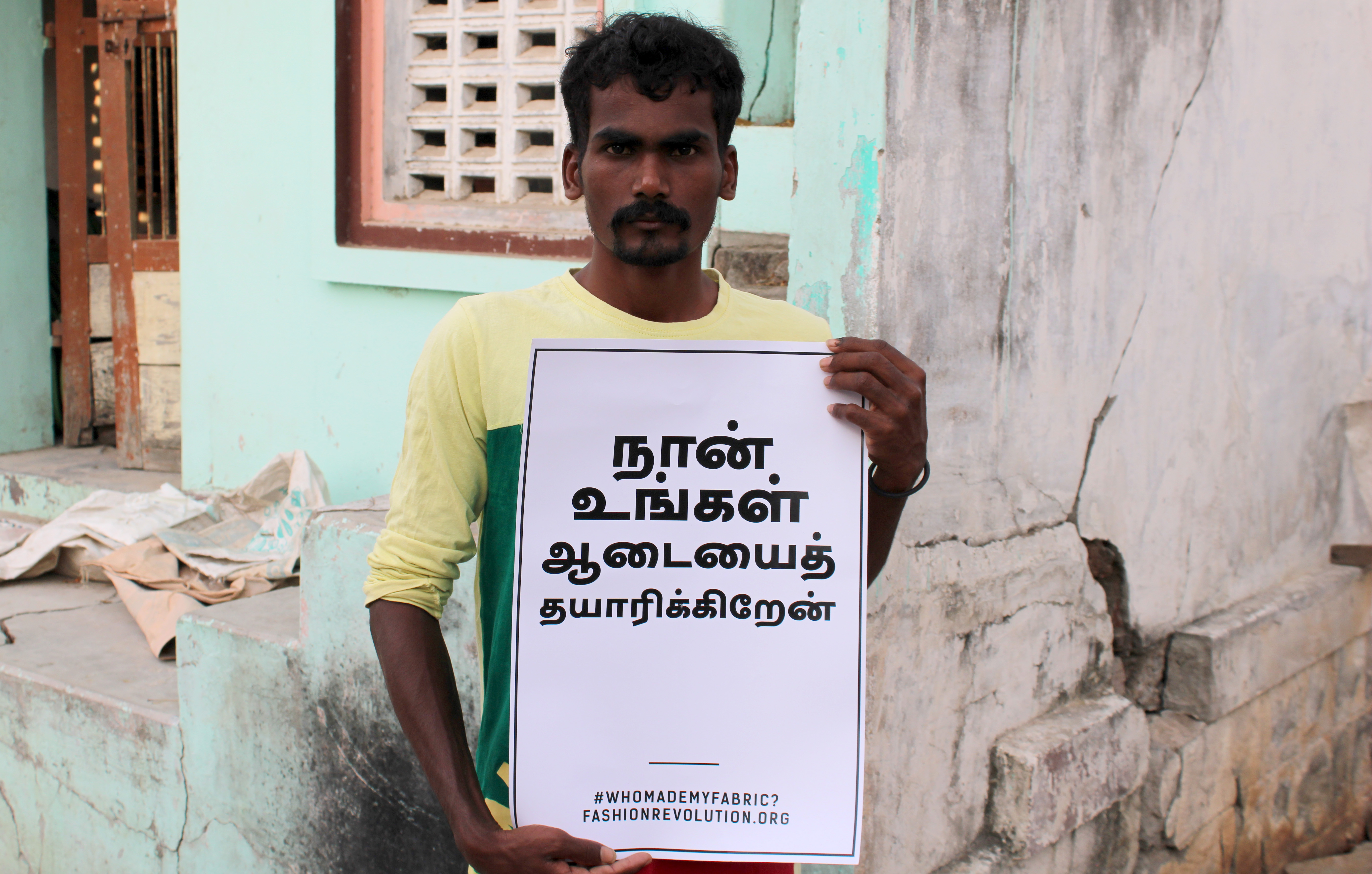

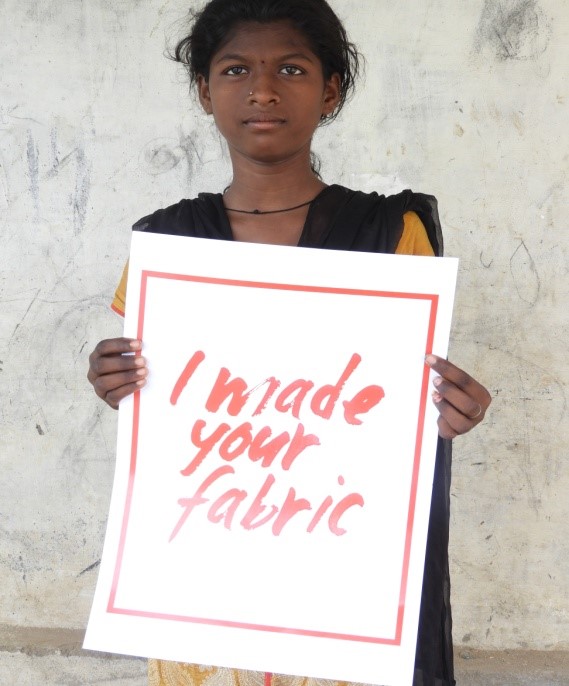

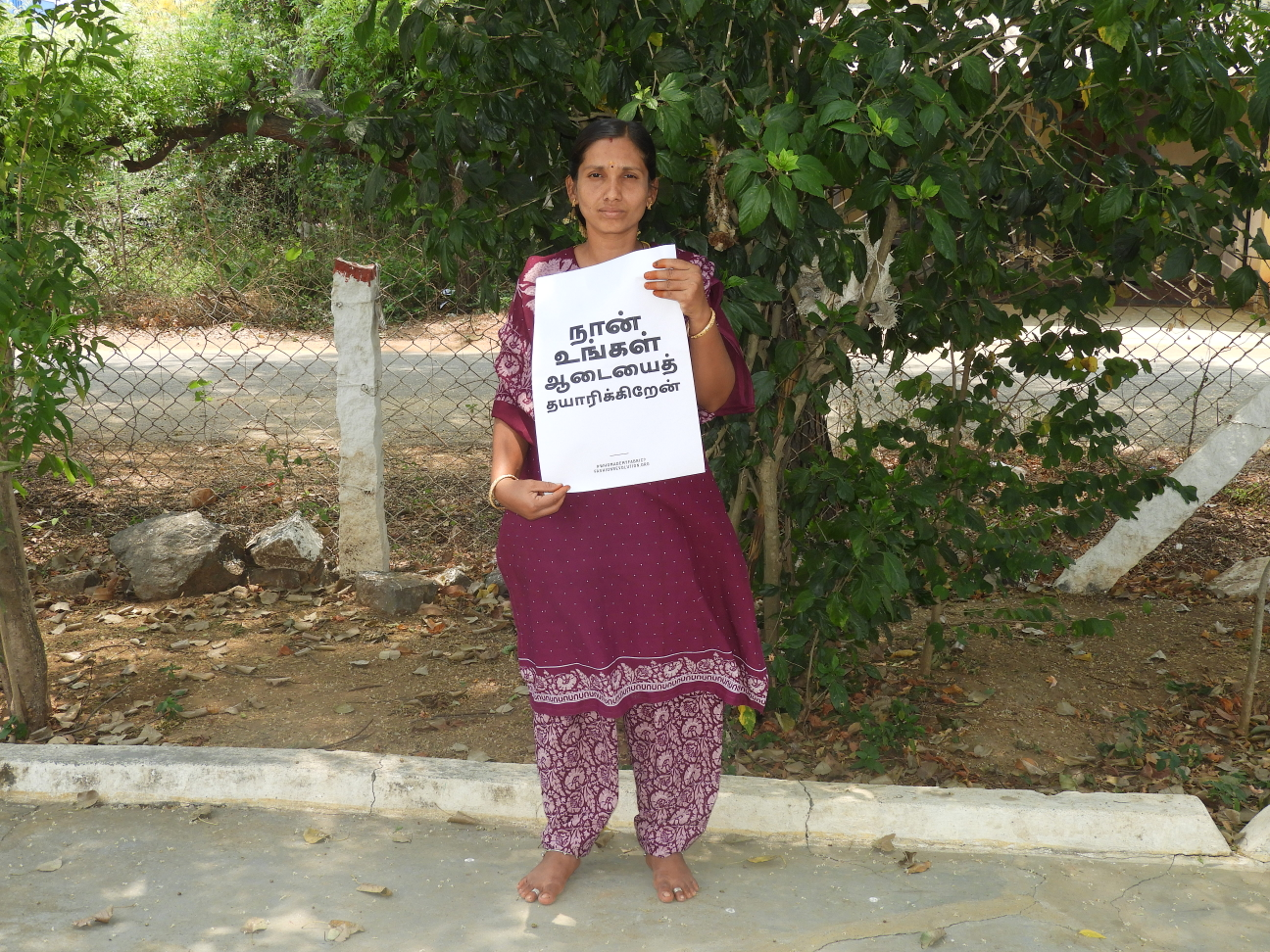

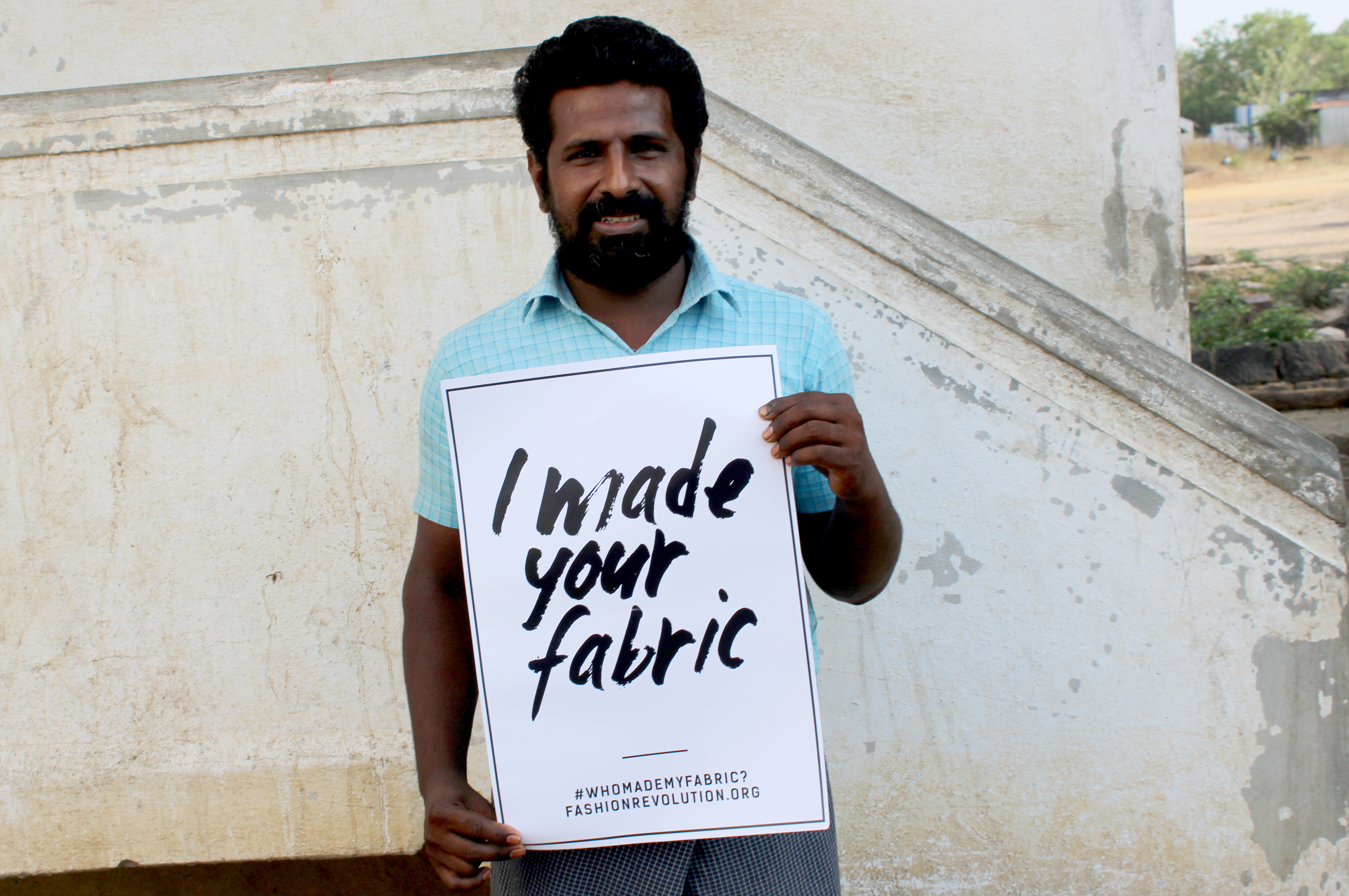

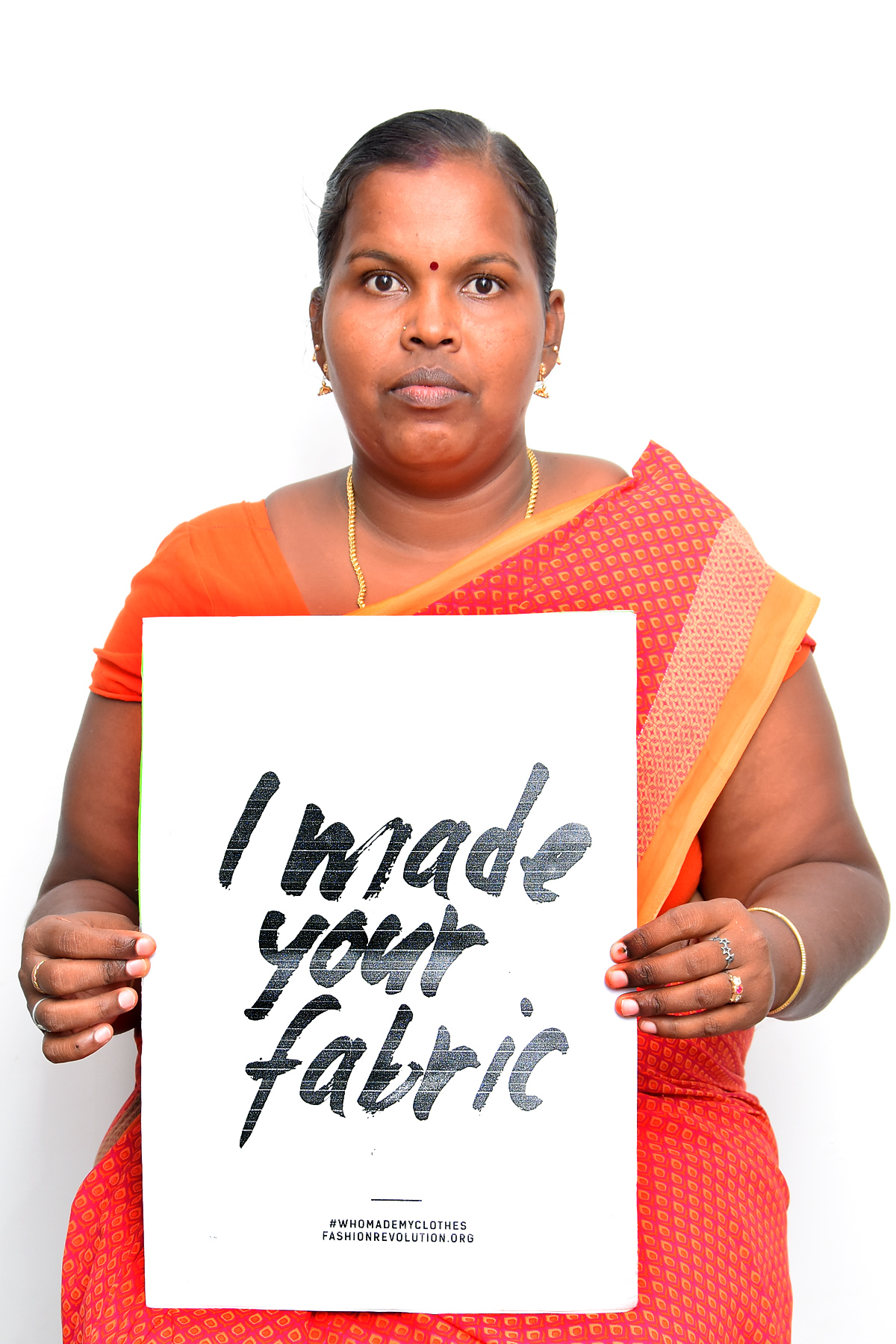

Tamil Nadu is the largest producer of cotton yarn in India with over 2,000 mills employing 280,000 workers that supply international fashion brands. The mostly young, female workforce face problems such as pay below the minimum wage, sexual harassment, dangerous working conditions and excessive overtime.

With the help of grassroots organisations in Tamil Nadu, we reached out to workers making clothes and fabrics for the fashion industry to ask them what they think about their work and what changes they would like fashion brands to help them make.

Some of the key themes that emerged from these interviews were that many workers said they like their jobs and are proud of the work they do. These are skilled workers that are demanding fairer working conditions for the work they are committed to excelling at. The areas that workers wanted to see change included low wages, long hours, excessive and unpaid overtime, lack of PPE and lack of sufficient rest breaks and leave.

We also heard about the lack of social security benefits such as ESI (Employee State Insurance) and EPF (Employee Provident Fund) that many informal, temporary or contract-based workers were particularly facing, in addition to issues such debt bondage and being driven to work far from home. There were also various gender-related issues arising, such as risks of verbal abuse and gender-based violence as well as lack of toilet facilities and period products.

Here, explore a small selection of the dozens of #IMadeYourFabric images we received in both English and Tamil language alongside biographies that each worker provided. We hope to share many more in the coming weeks.

Workers’ voices are central to our movement, so we aim to remove barriers between producers and consumers by sharing their stories in their own words. It is important to note that clear informed consent was provided from everyone involved in this campaign and various safeguarding measures were taken to ensure safety and confidence. We expect this same level of due diligence from any brands, suppliers or organisations sharing #IMadeYourFabric and #IMadeYourClothes content.

Mallika, 35

“I am Mallika, 35 years old. I am working in a textile mill in Namakkal District, Tamilnadu. I am working on yarn driving in the reeling section for the past 25 years. I like this job very much. I am working overtime but I don’t get a salary for it.”

Shenbagam, 33

“I am working in a private spinning mill that produces yarn for your shirts located at Virudhunagar District of Tamilnadu. I am working under the management for more than 10 years and I am not very healthy nowadays. Most of my earnings are spent on medicines and medical treatments. Because our working environment is not clean and PPEs are not provided properly. We wish to have a healthy working environment for me and for my colleagues.”

Amsaveni

“I am Amsaveni, living in Coimbatore District of Tamil Nadu, India. I worked in a power loom unit as a helper. The main problem faced by me in the workplace is the enormous heat problem in the machine. I got ill due to this workplace issue. The fashion industry supports us to bring change in our working conditions.”

Perumal, 33

“My name is Perumal and I am 33 years old. I have been a labourer in a private spinning mill located in Virudhunagar District of Tamilnadu, India. I have been working in the spinning mill for the past fifteen years without any basic facilities like restrooms, hygienic space for having food and without regular increment. I would like to have basic facilities and to receive proper papers for the deduction of my provident fund. So, I request the brands take steps to improve our working conditions.”

Devarini

“I am working in a spinning mill located at Virudhunagar District, Tamil Nadu. I am a spinning department worker. I like my job which is supporting to produce yarn. I need clean and sufficient toilets at my workplace. I request the brands to help to improve our working conditions.”

Ambika, 35

I am Ambika, 35 years old. I am working in a Textile mill located at Namakkal District, Tamilnadu. I am working on yarn driving in the reeling section for the past 10 years. I like this job very much. The spinning mill has all kinds of basic amenities. However, I don’t get a salary that suited my experience. The salary is not increased yet. I requesting the brands who are using our production to help us to raise our living standards by ensuring benefits of labourers.”

Eswari

“My name is Eswari from West Brooke in Kotagiri, The Nilgiris district, Tamil Nadu, India. I was worked in a textile mill in the Coimbatore district as a line supervisor. I felt safe in the workplace and hostel. But I could not get leave even in general holidays. The leave procedure was so tricky in my company. We also received very low wage and could not access the PF, ESI benefits. The fashion brands should address the issues like wages, leave and social welfare benefits of women workers.”

Bhuvaneswari

“I am Bhuvaneswari from Coimbatore district of Tamil Nadu, India. I am working in the yarn division of a cotton mill to make yarn and fabric from cotton. Supervisors should stop using abusive language against women in the workplace. The fashion industry should support to change this working environment.”

Rengaraj, 27

“I am Rengaraj aged 27 working in a private spinning mill located at Virudhunagar District of Tamilnadu, India. We have been paid very low, have no leisure and have not toilet facilities in my workspace. We would be grateful to if the above mentioned problems have been rectified.”

Karpagavalli

“I am working in a spinning mill located at Virudhunagar district of Tamilnadu. I am in helping the production of yarn in the spinning department. Napkins should be provided for women workers during our menstrual periods. Women are suffering a lot when they got periods during working days. I request the brands to improve our working condition.”

Jeyalakshmi, 45

“I am working in a spinning mill located at Tirunelveli District of Tamilnadu. I like my job but I am working on a contract basis so no permanency for my job. I want to change this condition. I request the fashion brands to support us to improve our working conditions.”

Tamilselvi, 32

“My name is Tamilselvi aged about 32 years. I am working in a garment factory located at Tirunelveli district of Tamilnadu. I like my job but I have to work for long hours without any break and I am getting a very low wage. I want to change my working conditions. I request the brands who are sourcing from my factory support us to improve our working conditions.”

Malathi, 38

“I am working in a spinning mill located at Tiruneveli district. I like my job but I need to stand long hours without break. My working environment is also not in clean and hygienic condition. I request the fashion brands to support us to improve our working conditions.”

Gokila

I” am P. Gokila working in a garment factory located at Pudukkottai District, Tamil Nadu, India. The government should implement Minimum Wage Policy for the welfare of the workers in the textile garment industry. Wage for overtime working hours to be provided to all women workers. The fashion brands must take responsibility on the issues of workers at workplaces.”

Shanthi, Dhivya, Susila

“We are working in a spinning mill located at Erode District. Though we are working twelve hours per day we only receive two hundred and thirty rupees as our salary. We expect minimum wage for our salary. We request the fashion brands to support to improve our working conditions.”

Ganesh, 49

“My name is Ganesh Babu aged about 49 years. I am working in a garment factory located at Tirunelveli district, Tamilnadu. I am working in the process of making fabric from yarn. I have to continuously stand a long time without any break. My workplace is not in clean and hygienic condition. My daily wage is also very low and I am working as a temporary worker. I want to change these working conditions. I request the brands who source from our region support us to improve our working conditions.”

Kavitha

“My name is C. Kavitha. I am from Dindigul District in Tamilnadu, India. I am working in a garment unit in our district. I stitch various types of dresses and other textile materials. I like my job of sewing clothes but I feel like I am not getting paid enough for the work I am doing. I kindly request the fashion industry that are using the threads that I am making to be responsible and support for the change of the working conditions in the spinning mills.”

Monika, Jayanthi and Sarathnizha

“We are working in a spinning mill located at Erode District. We like our job but due to lack of maintenance of machines and workload, our workers met accidents often. We also didn’t receive any accident damage from our management. We want to change this working condition. We request the fashion brands to improve our working conditions.”

Find out more about the #WhoMadeMyFabric campaign, including a tool for emailing brands that source fabrics in Tamil Nadu, and read the Out of Sight: A Call for Transparency From Field to Fabric report for more details.

Some English translations were edited for clarity.

This is a guest blog by Erinch Sahan, Chief Executive of World Fair Trade Organization, one of our partners for Fashion Revolution Week 2021.

Fashion is broken. Ridden with the exploitation of people and planet, we are all beginning to see big changes are needed. Workers and farmers remain trapped in poverty and our treadmill of fast fashion is also exhausting our planet’s resources while generating waste and pollution. All to produce clothes and accessories that are disposed of after making a few appearances.

In response, a new approach is taking root. It is based on putting artisans, workers and producer communities at the heart of the fashion industry. It fosters and empowers social enterprises who are embedded in their communities, who exist to benefit artisans and workers while protecting the planet.

To illustrate, take Manos del Uruguay, a fashion producer and brand owned by 12 women’s producer cooperatives across Uruguay. Founded in 1968, it is an enterprise that exists to serve these artisans. All profits are reinvested to benefit these artisans while on a journey to grow its brand. Of the 12 producer cooperatives that own and control Manos, two specialise in dyeing the yarn, and the ten others knit or weave the products. The board of Manos is made up of artisan representatives. This is a stark contrast to the profit-maximising models of mainstream fashion who have no accountability to the workers and artisans behind their products. The business model underpinning Manos is key. It allows for a mission-led enterprise that’s committed to its communities.

There are 400+ such Fair Trade Enterprises from 79 countries. Take for instance Mahaguthi from Nepal, a social enterprise that reinvests 100 per cent of their profit into supporting their producers and communities. Their business model means they can support artisans from 15 districts in Nepal, and invest in production from local natural fibres, such as nettle. The examples go on, from Earth Heir and Biji Biji in Malaysia to Ellilta and Sabahar in Ethiopia. From AHA and Artsol in Bolivia to Freeset and Creative Handicrafts in India. What they have in common is a mission-led model, built first and foremost to benefit the artisans and their communities and unlocking profound ecological innovation and artisanal quality.

This model of production is evolving in diverse ways. The approach varies greatly, based on the local context and is built to work for the specific community. At its heart is an enterprise producing fashion items, which is truly mission-led, able to navigate the trade-offs in favour of workers and artisans, while remaining deeply embedded in its community. The reinvestment of profits and full adoption of the 10 Principles of Fair Trade are important features that lock in this social mission. This enables the social enterprise to shape production around local concerns.

Ecologically, this unlocks a range of important practices. For instance, indigenous techniques such as local hand-weaving or metal-work techniques can become the centre-piece of the production model, as is the case of Yabal of Guatemala. These are low and sometimes zero-carbon models of production that wouldn’t be embraced by mainstream fashion businesses that are looking only at short-term cost-cutting. Yet they prioritise the use of locally available natural fibres and dyes, recycling and upcycling of available materials, and ensuring local resources like waterways are protected. And it turns out the majority of their CEO and board members are women, again in stark contrast to the male-dominant board rooms and C-suites of mainstream business.

Artisan production can also change the relationship between consumers and their fashion items. A handwoven garment or a handmade piece of jewellery is more likely to be treasured, as we connect across borders with the makers of our products. The authentic stories can connect hearts and minds, leading to fewer but more loved products in our closets. The product lifecycle can be significantly extended through artisanal production.

What does all this mean for the future of fashion? Consumers and citizens are demanding change. And this change needs to work for people and the planet. Artisans the world over have created models of production that are in harmony with their local ecosystem and their societies. To embrace these models, we need enterprises that are tailored for them, not ones that exploit them. Fast fashion and profit-maximising business models are not the right fit. What’s working is the combination of social enterprise plus Fair Trade plus artisan-led production. The enterprises of the WFTO community are doing just this – the proof of concept can be found at wfto.com/fashion.

The narrative of fashion needs to be turned upside down. But there is a danger that we embrace the rhetoric while remaining trapped in the business and production models that are no longer fit-for-purpose. Do we have the courage to explore a new alternative? Artisans and their Fair Trade Enterprises may be offering us that chance.

Nasreen Sheikh, child labour and forced marriage survivor, social entrepreneur and gender equality advocate, shares her journey from exploitation to empowerment with Fashion Revolution.

My work as a young female social entrepreneur was first documented publicly by Forbes in 2012, but I’ve been actively organising women to work and protect each other since I escaped child slave labour in the garment industry in Kathmandu when I was about 12 years old. Due to my birth being undocumented, like most births where I was born, I’m not sure how old I am. My guess is 27 to 29 years old. From the moment of birth, the society of the rural village I come from teaches female children that their existence is insignificant. If one’s own birth does not matter, then the conditions in which she lives, works, strives, suffers, and dies also do not matter. At an early age I came to believe that girls are simply commodities that are bought and traded as such. We are not human beings.

Growing up, I witnessed unconscionable atrocities against children and women, including some of my own female family members being murdered for speaking up for themselves. By age 9 or 10, my life seemed destined for the same oppressive path. So, I escaped my village for the capital city of Kathmandu, where I worked 12-15 hours per day in a textile sweatshop as a child labourer, receiving less than $2 per gruelling shift — only if I completed the hundreds of garments demanded of me. I ate, slept, and toiled in a sweatshop workstation the size of a prison cell, often picking sewing threads out of my food and being too afraid to look out the window. I was surrounded by pieces of clothing day and night. I HATED those clothes. They were woven with the energy of my suffering. At the end of each day, I would collapse onto the large bundles of clothes and daydream about where they would end up and who would wear them. Some of you may be wearing those clothes right now.

As a young village girl, I would look at the stars and think about the connection of all things throughout the universe. Had I not become a lifetime advocate for ending slavery, I would’ve loved to become an astronomer. I’m fascinated by stars. I’ve come to love a quote of Carl Sagan’s: “The cosmos is within us. We are made of starstuff. We are a way for the universe to know itself.” I believe everyone on this planet and all life is in a reciprocal relationship, where each individual action affects the whole. This understanding has been deeply integral to the holistic approach I’ve created to incorporate all 17 sustainable development goals into my work.

I’m currently accomplishing these goals by building women’s empowerment training centres through my non-profit organisation, Empowerment Collective, and my social fashion business, Local Women’s Handicrafts. I organised hunger relief efforts during the 2015 Nepal earthquake, helping thousands of women feed their families, and more recently, we served over 360,000 meals to rural villages affected by COVID 19. In an effort to support women’s hygiene, we’ve distributed over 7,500 menstruation hygiene kits since 2014. Additionally, we brought the first water sanitization system to a rural village in Nepal, where 71% of its water sources were toxically polluted.

Our online store is bringing ethical and fair-trade goods to the world and we’re sharing the stories of the women who produce our sustainable fashion products. Our empowerment centres use affordable, clean, and sustainable energy by utilising both solar power and bio-gas units. We’ve shown innovation in the fashion industry by using recycled materials and non-electric looms to create our products, while preserving generations-old handicraft traditions. We’ve reduced income inequality by training women in a country where currently only 0.01% of business owners are women. In an effort to promote a more sustainable city, we’ve distributed thousands of reusable shopping bags in Kathmandu, one the most polluted cities in Asia. We’ve also been advocating for responsible consumption through our million-mask initiative that’s been teaching people to use sustainable, reusable masks during the COVID-19 epidemic. Our use of natural dyes in our production process takes into account the effect we have on life below water, and the textile developments we’ve created in collaboration with local hemp farmers support life on land as well as local animal habitat preservation.

Since 2008, we’ve offered quality education through 1,950 skills training program workshops, educating over 5,000 women with real-world working skills. After becoming the first girl in my village to ever escape forced marriage, I’ve been an outspoken proponent of gender equality. We also provide women with decent work and economic growth by following the 10 principles of fair trade. We honour the concept of peace, justice, and strong institutions by creating safe space centres for women to work in areas where they are most at risk. In order to reach our goals, we’ve partnered with many different organisations, including Fashion Revolution, LA Summit, Activists and several universities.

Follow @_NasreenSheikh and @Empowerment_Collective to keep up with Nasreen’s work.

The fashion industry has seen enormous upheaval over the last couple of months. As we edge into the post lockdown period, we at The Seam wanted to pause and take some time to reflect on how people’s personal relationships with their wardrobes have changed during COVID-19.

The Seam is an online marketplace that matches people who can sew with local demand, allowing consumers to find immediate help with clothes repairs and customisations. In April 2020, we launched an online survey* and discovered that people are now gravitating towards more mindful relationships both with their clothes and the communities around them.

Make do and mend culture

Some 64% of the people we surveyed now prefer to repair damaged clothes rather than throw them out. Whilst 6 out of 10 of us are actively trying to improve the way we care for our clothes and accessories. Both of these changes are down to the fact that many of us suddenly had a chance to stop and think about our behaviours as lockdown set in. With no one to see and nowhere to go, and the possibility of reduced income, suddenly our piles of unworn clothing took on new significance.

People have been using this time to think more broadly about their impact on the world. Google trends found in April that over the previous 90 days, search interest in “How to live a sustainable lifestyle” increased by more than 4,550%. And almost half (45%) of the people we surveyed said they had learned they need less stuff in order to be happy.

Love thy neighbour

In tune with what we’ve been reading in the news about increased community spirit, we also found that 42% of people would like to increase their purchases of locally bought clothes. However, when we asked the same people to name fashion businesses local to them, the average number of brands they could come up with was between 0-1, signalling a significant need for increased awareness and support in promoting small businesses.