Who Tanned The Leather For Your Designer Bag?

In transit from Bangladesh to Manchester, I walked past the luxury stores in Dubai airport, all of which have leather bags displayed in their windows. The spotlights in the store windows shine down on an array of beautiful bags, but I want to shine a spotlight on a darker story which needs to be revealed. The previous day I had visited the tanneries in Dhaka, Bangladesh, where the leather used for many of the world’s designer bags and shoes originates.

Until recently, the district of Hazaribagh housed the majority of Bangladesh’s tanneries. Not only did severe labour abuse, including child labour, take place but decades of untreated chemical waste has poured into the local Buriganga river, affecting local communities and habitat. In particular, chromium from the tanneries has affected fish populations on which the red-listed endangered Ganges river dolphins prey. Concentrations of chromium are up to 100 times the level prescribed by the World Health Organisation for drinking water.

In an attempt to improve conditions for workers and prevent further environmental pollution in the growing leather sector, the government of Bangladesh decided to relocate the tanneries from Hazaribagh to Savar. The move has been beset by delays: initially scheduled for 2005 completion, an article in Bangladesh’s Daily Star newspaper on 8 November reported that the project has been delayed yet again and they are now aiming for completion in June 2019.

Meanwhile, 92 of the 155 tanneries have already been relocated to Savar, most of which have double the land and therefore at least double the production capacity of their previous facilities. However, the infrastructure and utilities for the tanneries are from adequate, whilst facilities for relocated tannery workers do not even meet their basic necessities of housing, health, education and transportation.

I was visiting unannounced, hoping to talk to workers and managers about the environmental and social problems created by the move. I followed a truck piled high with hides into the Savar Tannery Estate. The smell was a good indication we were approaching the tanneries – a powerful odour which intensified on approach.

The roads were not only potholed, but were covered in surface effluent. The Central Effluent Treatment Plant for the new Savar Tannery Estate is not yet fully functional, drainage systems are not in place and tannery effluent is flowing into local drainage ditches and into the Dhaleswari river. According to the Rapid Assessment of Hazaribagh Tanneries report recently published by SANEM, analysis of data and samples collected at discharge points from the treatment plant, as well as from the Dhaleshwari river, have produced alarming results. Everywhere I looked, drainage ditches were visibly flowing with chemical effluent, with one drain running behind a row of food stalls serving meals to the tannery workers. The government shifted the tanneries due to pollution of the river but ultimately the same thing is happening in Savar.

As I walked from the car towards the first factory I spotted something else on the road – animal tails lying discarded on the ground. Solid waste is being dumped in the streets because a protected dumping yard has not yet been set up.

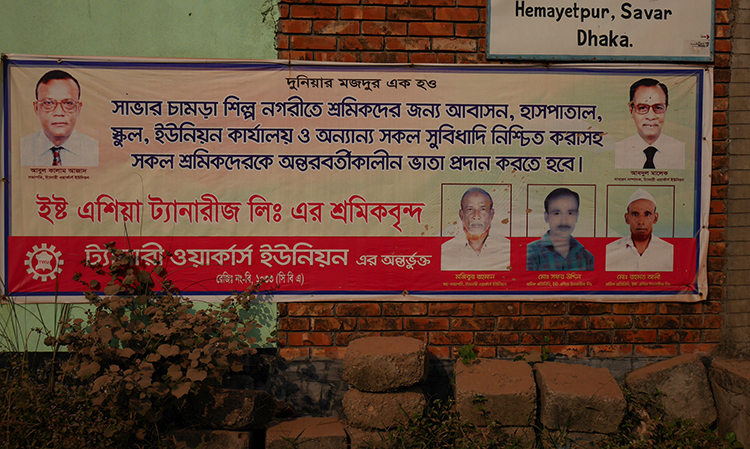

Environmental issues are not the only problems caused by relocating the tanneries before the infrastructure is complete. A sign outside a factory, put up by the Tannery Workers Union, says: “We demand hospital, residence, school, development centre and other benefits should be assured and all past dues should be settled for the workers.”

In the first factory I visited, the foreman was candid about what the urgent improvements needed within the locality. “If there is a serious injury we can’t get the worker to hospital on time. There are no primary healthcare services here. A lot of our workers need ongoing medical support due to skin rashes but we don’t have such facilities here. There is almost no accommodation in the area. There is some but it is expensive so the workers have to commute for 120 taka each way every day (£1.10) and it takes 1.5 to 2 hours. 95% of our country is Muslim yet we don’t have a mosque here.”

I also observed many young workers in the factories, all working without any protective equipment. The sector has an 11% child labour rate, but there is also a problem with young labourers on apprenticeships who should be aged 16 to 17, but often start at 15. Apprentices are allowed to work 30 hours over a six-day week, plus 6 hours maximum overtime across the week, but they are working far more in the tanneries.

Returning to Dhaka, I visited the offices of Awaj Foundation where I talked to Nahidoc Hasan Nayan, Director of Operations, about the tanneries and what steps needed to be taken in order to resolve the myriad problems I had seen that morning. Accommodation costs in Savar are very high compared to Hazaribagh and housing is insufficient, but if workers don’t move the high cost of the commute means their real wages have decreased and they are working below the poverty line. The workers also need schools for their children and medical facilities, which are currently 10-15km from the tanneries. If a factory has 150 workers they should by law have first aid inside the factory but this is not happening. It could easily take over an hour to get to medical facilities due to the traffic jams. Workers are not using personal protective equipment so the risks are high. There is one union for tannery workers, but according to Mr Nayan it is working for the factory owners not the workers.

“Workers are worse off,” stated Mr Nayan,“I found 12 year old boys there last week who have no idea they are working in such a dangerous place.

Part of the problem is that brands don’t come to the tanneries; buyers only engage with the factories,” he continued.

Although the foremen in the tanneries did not know for which brands the leather was destined, I was told in one of the tanneries that the leather would be sent to China and Italy. In Fashion Revolution’s 2017 Fashion Transparency Index which reviews and ranks 100 of the biggest global fashion and apparel brands and retailers according to how much information they disclose about their suppliers, supply chain policies and practices, and social and environmental impact, we found that only 14% of brands were publishing their second tier factories, which sometimes includes tanneries. No one is publishing a list of raw material suppliers, so there is no way for consumers to know where the leather comes from or what animal welfare standards are in place.

The leather and footwear industry is the second largest revenue generator in Bangladesh. Although far behind the Ready-Made-Garment sector at $2 billion USD compared to $28 billion USD, footwear production is expected to become the next area of growth in Bangladesh, putting more pressure on the tanneries as they meet increased demand. The footwear industry comprises 35-50% women but they are not getting maternity leave, nor are workers receiving medical leave or holidays, only festival leave. Not all are getting minimum wage in both the tanneries and the footwear factories, particularly in smaller factories. According to Mr Nayan, only 5-10% of the factories have adequate working conditions.

The move to Savar was planned as a means of improving social and environmental standards but quite the opposite has occurred. So what needs to happen now? Workers urgently need compensation for the wages they lost during the 3 to 4 month transition period from Hazaribagh to Savar when they were unable to work. Transportation must also be organised for workers until affordable, local accommodation is in place. The Central Effluent Treatment Plant urgently needs completion as the current situation is just moving environmental pollution from one site to another. Ultimately, all stakeholders need to take measures to improve working conditions, benefits and health and safety standards so this move has a positive long-term effect on the environment, workers and their families.

As consumers, we can also play a part by asking the question #whomademyclothes, telling brands we need more transparency in fashion supply chains right back to the tanneries and the raw materials.

Many of the social and environmental problems we are seeing in the tanneries are the same ones that beset the garment factories from their inception in the early 1980s until post- Rana Plaza scrutiny started to bring about change. As the leather sector expands in Bangladesh, let’s not make the same tragic mistakes we made with the garment industry.

Carry Somers visited Bangladesh as a guest of the Bangladesh Denim Expo which this year had a focus on Transparency.

For further information on the Rapid Assessment of Hazaribagh Tanneries report, see SANEM

Textile Exchange has set up the Responsible Leather initiative to create responsibility in the leather supply chain.