Plastic is designed to last forever, but we are using it to design products, including clothing and its related packaging, that are only used once. Around two thirds of our clothes are made from synthetic fibres, such as polyester, acrylic and nylon, which are all plastics. The process of turning fossil fuels into textiles for our clothes releases significant amounts of Greenhouse Gases.

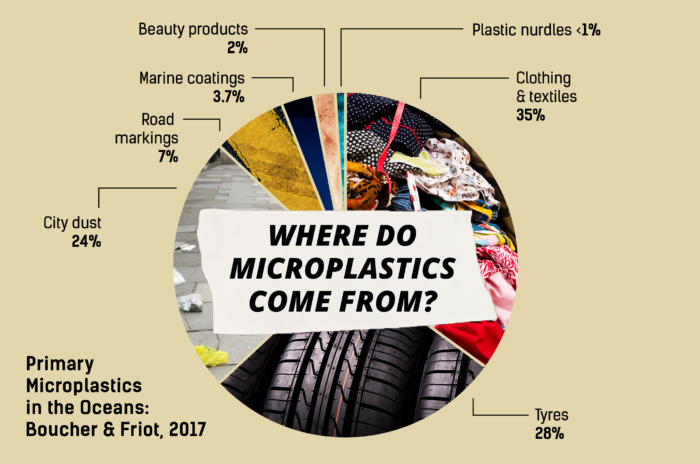

Fashion’s impact on the environment doesn’t stop once our clothes are made. Textiles are the largest source of both primary and secondary microplastics, accounting for 34.8% of global microplastic pollution1, with around 700,000 microfibres being released in every wash cycle2. These microfibres enter our sewage system and many are too small to be collected by the wastewater treatment plants. Even those microfibres which are captured can end up in our oceans as treatment plant sludge is frequently used as a fertiliser on fields, from which it enters waterways and, in the end, the sea.

It has been estimated that 1.4 million trillion microfibres are currently in the oceans3 and if the fashion industry continues in a business-as-usual scenario, between 2015 and 2050, 22 million tonnes of microfibres will enter our oceans4. Recent research shows that plastics emit powerful greenhouse gases as they degrade and, over time, give off more and more gas, so the plastics accumulating in our oceans represent a vast, uncontrollable source of future emissions, as well as posing a danger to our marine ecosystems and to human health.

The fourth edition of Fashion Revolution’s Fashion Transparency Index, launched in April 2019, ranks 200 of the world’s largest fashion brands and retailers according to their level of transparency. It measures how much information brands disclose about their suppliers, supply chain policies and practices, and social and environmental impacts. In April 2020, the fifth edition will be published, covering 250 brands and retailers. Five key areas are assessed: Policy & Commitments, Governance, Traceability, Know, Show & Fix which looks at how brands assess their suppliers and how they work to fix any problems and Spotlight Issues, which in 2019 focused on the the SDGs, the Sustainable Development Goals.

In terms of SDG12 Responsible Production and Consumption, whilst 43% of brands are publishing a sustainable materials strategy or roadmap, only 29% are disclosing the percentage of their products that are made from sustainable materials and just 15% publish measurable, timebound targets for the reduction of virgin plastics. Only 26% of brands explain how they are investing in circular solutions to reduce textile waste. In our 2020 Index, one of our Spotlight Issues will be Composition, looking at how brands and retailers are reducing salient environmental risks through material selection, the elimination of hazardous chemicals and moving towards circularity. As part of this section, we will be looking for disclosure on what the brands are doing to minimise the impact of microfibres.

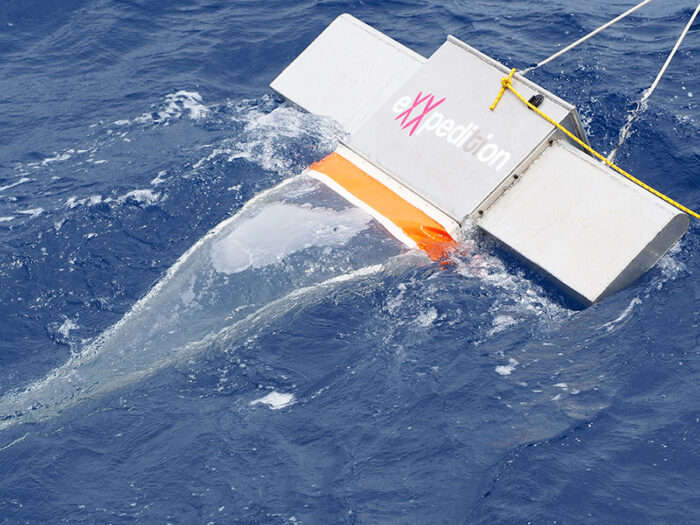

As we sail from Galápagos to Easter Island with eXXpedition, the analysis of polymer types from the plastics we collect will be invaluable for those brands who are committed to acting to reduce microfibre shedding and microplastics in our environment as they will be able to better understand the density and distribution in the oceans of the different plastic fibres found in our clothing so they can prioritise actions to reduce the areas of greatest impact.

However, there are no simple solutions when it comes to materials. A polyester shirt can have more than double the carbon footprint of a cotton shirt, but synthetic fibres generally have less impact on water and land than cotton5. Synthetic fibres made from recycled materials such as crushed plastic bottles or reclaimed fishing nets have around 50% lower emissions than using virgin fossil fuels6 but the microfibre release is likely to be the same.

Building a more sustainable fashion industry and curbing its destructive impact on our oceans will entail governments, brands, retailers and citizens all taking action together to help bring about the systemic change needed to end the exploitation of our planet.

Governments must act urgently to deal with fashion’s escalating environmental problem and as these solutions will, in turn, help tackle climate change, this should be a win-win. We are currently allowing companies to evade responsibility for their environmental impacts, so we also need to see mandatory due diligence and reporting for all major brands and retailers. Legislation should also be passed requiring all new washing machines to be fitted with effective filters to ensure maximum capture of microfibres.

Brands and retailers must change their business models and create products with longevity and quality. They must understand the true value of materials, which should be mindfully designed, redesigned and recuperated as a valuable resource. Brands must set Science-Based Targets and report annually on their progress. And they must use sustainability to drive all aspects of their business.

It can be hard to know how best to care for our clothes as research on reducing microfibre shedding is limited and, at times, contradictory. Recent advice suggests short cycles, using liquid detergent and fabric softener and washing at a low temperature. What is certain is that the best way to reduce microfibre shedding is to wash our clothes less frequently. We can also rethink the fibres in our wardrobe and choose wisely when buying new clothes.

Finally, we can all use our voice and our power to demand that brands and legislators work to reduce the trillions of microfibres flooding into our waterways. That’s why Fashion Revolution has just launched a new hashtag #WhatsInMyClothes.

Fashion Revolution’s Manifesto states, “Fashion conserves and restores the environment. It does not deplete precious resources, degrade our soil, pollute our air and water, or harm our health. Fashion protects the welfare of all living things and safeguards our diverse ecosystems”. If we all work together, we can, and must, create a global fashion industry that conserves and restores the environment and values the wellbeing of everyone and everything living on this earth and in our oceans over growth and profit.

[1] Boucher and Friot, 2017

[2] Napper and Thompson, 2016

[3] Leonard, 2016

[4] Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017

[5] Olivetti et al., 2015

[6] Textile Exchange, 2017

During the month of February, we’ve been exploring fashion’s impact on water and looking at how we can practice water stewardship through our wardrobes. So far, we’ve discussed the consequences of industrial dyes, misconceptions around water consumption, and better laundry habits to conserve water. Now, we’re taking a look at how our wardrobes affect our oceans when they release microfibres.

What are microfibres?

Microplastics are tiny plastic pieces that are less than <5 mm in length. Textiles are the largest source of primary microplastics (specifically manufactured to be smaller than 5mm), accounting for 34.8% of global microplastic pollution [1]. Microfibres are a type of microplastic released when we wash synthetic clothing – clothing made from plastic such as polyester and acrylic. These fibres detach from our clothes during washing and go into the wastewater. The wastewater then goes to sewage treatment facilities. As the fibres are so small, many pass through filtration processes and make their way into our rivers and seas.

Around 50% of our clothing is made from plastic [2] and up to 700,000 fibres can come off our synthetic clothes in a typical wash [3]. As a result, if the fashion industry continues as it is, between the years 2015 and 2050, 22 million tonnes of microfibres will enter our oceans [4].

What impact do microfibres have on the environment and on human health?

Due to the tiny size of microplastics, they can be ingested by marine animals which can have catastrophic effects on the species and the entire marine ecosystem.

Microfibres can absorb chemicals present in the water or sewage sludge, such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and carcinogenic Persistent Organic Pollutants (PoPs). They can also contain chemical additives, from the manufacturing phase of the materials, such as plasticisers (a substance added to improve plasticity and flexibility of a material), flame retardants and antimicrobial agents (a chemical that kills or stops the growth of microorganisms like bacteria). These chemicals can leach from the plastic into the oceans or even go straight into the bloodstream of animals that ingest the microfibres. Once ingested, microfibres can cause gut blockage, physical injury, changes to oxygen levels in cells in the body, altered feeding behaviour and reduced energy levels, which impacts growth and reproduction [5][6]. Due to this, the balance of whole ecosystems can be affected, with the impacts travelling up the food chain and sometimes making their way into the food we eat! It has been suggested that people that eat European bivalves (such as mussels, clams and oysters) can ingest over 11,000 microplastic particles per year [7].

What can fashion brands do?

The fashion industry needs to take responsibility for minimising future microfibre releases. Brands can have the most impact if they take microfibre release into consideration at the design and manufacturing stages. Designers should consider several criteria in order to minimise the environmental impact of a synthetic garment [3]:

- Use textiles which have been tested to ensure minimal release of synthetic microfibres into the environment.

- Ensure the product is durable so it remains out of landfill as long as possible

- Consider how the garment and textile waste could be recycled, to achieve a circular system.

During manufacture, there are several methods that can be applied to reduce microfibre shedding such as brushing the material, using laser and ultrasound cutting [4], coatings and pre-washing garments [1]. The length of the yarn, type of weave, and method for finishing seams may all be factors affecting shedding rates. However, much more research from brands needs to occur in order to determine best practices in reducing microfibres and create industry-wide solutions.

Waste-water treatment…

Waste-water treatment plants (where all our used water gets filtered and treated) are currently between 65-90% efficient at filtering microfibres [6]. Research and innovations into improving the efficiency of capturing microfibres in wastewater treatment plants is essential to prevent them escaping into our environment.

Washing machine filters…

Improving and developing commercial washing machine filters that can capture microfibres may allow for an additional level of filtration, whilst also educating consumers and businesses [8]. However, current filters which need to be fitted by the user, such as that developed by Wexco, are currently expensive and reportedly difficult to install. They also place a financial burden upon the consumers, rather than pressurising brands to commit to change. To tackle this, we need more industry research and legislation to ensure all new washing machines are fitted with effective filters to capture the maximum amount of microfibres possible. However, we then have the issue of what to do with the microfibres once we have caught them – an area which requires more research and industry collaboration.

Collaboration is key

Collaboration across multiple industries is required if we are to tackle microfibre pollution. In addition to material research, waste management and washing machine research and development, there is a role for other sectors such as detergent manufacturers and the recycling industry to come together to help reduce microfibre pollution. Cross-industrial agreements could help promote collaboration between industry bodies and promote sharing of resources and knowledge.

A major issue has been a lack of a standardised measure of measuring microfibre release. However, a cross-industry group, The Microfibre Consortium recently announced the first microfibre test method. The launch will enable its members (including brands, detergent manufacturers and research bodies) to accelerate research that leads to product development change and a reduction in microfibre shedding in the fashion, sport, outdoor and home textiles industries. The Microfibre Consortium also works to develop practical solutions for the textile industry to minimise microfibre release to the environment from textile manufacturing and product life cycles.

The need for microfibre legislation

Comprehensive legislative action is needed to send a strong message and force the brands to address microfibre releases from their textiles. This is a complicated issue that will require policymakers to tackle this issue on many different levels and sectors. Currently, there are no EU regulations that address microfibre release by textiles, nor are they included in the Water Framework Directive.

However, there have been several developments in microfibre legislation in the past few years:

- As of February 2020, Brune Poirson, French Secretary of State for the Ecological and Inclusive Transition, is the first politician in the world to pass microfibre legislation. As of January 2025, all new washing machines in France will have to include a filter to stop synthetic clothes from polluting our waterways. This makes France the first country in the world to take legislative steps in the fight against plastic microfibre pollution. The measure is included in the anti-waste law for a circular economy.

- In 2018, US states of California and Connecticut proposed legislation which would see polyester garments legally required to bear warning labels regarding their potential to shed microfibres during domestic washing cycles. However, this legislation is yet to be passed.

- In 2019, the EAC urged the UK government to accelerate research into the relative environmental performance of different materials, particularly with respect to measures to reduce microfibre pollution, as part of an Extended Producer Responsibility scheme. However, the UK government rejected the proposal stating that current voluntary measures are sufficient.

What can you do?

Write to your policymaker

It is vital that policy is put into place to tackle microfibres, such as the new French washing machine filter legislation. If you are concerned about microfibres, we encourage you to write to your policy representative and urge your government to take action on microfibre pollution. Now that France has enacted the microfibre legislation, it raises the bar for other governments to also take action, but they will only do so with enough pressure from the people they represent – you!

Changing your washing practices

The easiest thing you can do to minimise microfibres releasing from your clothing is to simply wash your clothes less. Given that up to 700,000 microfibres can detach in a single wash [3] ask yourself if that item really needs to be washed or can it be worn once or twice more before you do?

While some research suggested using a liquid detergent, lower washing machine temperatures, gentler washing machine settings [3] and using a front-loading washing machine [9] can reduce microfibre shedding. Researcher Imogen Napper stated they found that there was no clear evidence suggesting that changing the washing conditions gave any meaningful effect in reducing microfibre release.

You can also use a Cora Ball, a guppy bag or a self-installed washing machine filter to capture microfibres from your clothing. The CoraBall and Lint LUV-R (an install yourself washing machine filter) have been shown to reduce the number of microfibres in wastewater by an average of 26% and 87%, respectively [10]. Although these can’t solve the problem, we still want to divert as many microplastics as we can from entering our waterways.

Should we all switch from synthetic fibres?

While many people’s first instinct is to switch from synthetic materials to natural materials to minimise microfibre release, this is not always a simple choice as there are other sustainability aspects involved. The UK’s Environmental Audit Committee in their report states ‘A kneejerk switch from synthetic to natural fibres in response to the problem of ocean microfibre pollution would result in greater pressures on land and water use – given current consumption rates’ [11].

Demand brands to do more to take action on microfibres

“Ultimate responsibility for stopping this pollution, however, must lie with the companies making the products that are shedding the fibres.” states the Environmental Audit Committee [11], but there are still too many major fashion brands not taking responsibility for what happens in their supply chains and in the life cycle of their products. As well as demanding action from your policymaker, we should also ask brands what they are doing to minimize the microfibre release from their products. It is clear that there is still a lot of work to do, and as their customers, we have a lot of power in influencing the impacts of the brands we buy.

The impacts of microfibres on the environment can be mitigated, but only with systematic and meaningful change supported by policymakers, brands, industry, NGOs and citizens all working together.

References

[1] Boucher, J. and Friot, D. (2017). Primary Microplastics in the Oceans: A Global Evaluation of Sources. IUCN. Available at: https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/2017-002-En.pdf

[2] Textile Exchange (2019). Preferred Fiber and Material Market Report. Available at: https://store.textileexchange.org/wp-content/uploads/woocommerce_uploads/2019/11/Textile-Exchange_Preferred-Fiber-Material-Market-Report_2019.pdf

[3] Napper, I. and Thompson, R. (2016). Release of synthetic microplastic plastic fibres from domestic washing machines: Effects of fabric type and washing conditions. Marine Pollution Bulletin. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0025326X16307639?via%3Dihub

[4] Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2017). A new textiles economy: Redesigning fashion’s future. Available at: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/assets/downloads/publications/A-New-Textiles-Economy_Full-Report_Updated_1-12-17.pdf

[5] Koelmans, A., Bakir, A., Burton, G. and Janssen, C. (2016). Microplastic as a Vector for Chemicals in the Aquatic Environment: Critical Review and Model-Supported Reinterpretation of Empirical Studies. Environmental Science & Technology. Available at: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acs.est.5b06069

[6] Henry, B., Laitala, K. and Grimstad Klepp, I. (2018). Microplastic pollution from textiles: A literature review. Consumption Research Norway SIFO. Available at: https://www.hioa.no/eng/About-HiOA/Centre-for-Welfare-and-Labour-Research/SIFO/Publications-from-SIFO/Microplastic-pollution-from-textiles-A-literature-review

[7] Van Cauwenberghe, L. and Janssen, C. (2014). Microplastics in bivalves cultured for human consumption. Environmental Pollution. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0269749114002425

[8] Browne, M., Crump, P., Niven, S., Teuten, E., Tonkin, A., Galloway, T. and Thompson, R. (2011). Accumulation of Microplastic on Shorelines Worldwide: Sources and Sinks. Environmental Science & Technology. Available at: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/es201811s

[9] Hartline, N., Bruce, N., Karba, S., Ruff, E., Sonar, S. and Holden, P. (2016). Microfiber Masses Recovered from Conventional Machine Washing of New or Aged Garments. Environmental Science & Technology. Available at: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acs.est.6b03045

[10] McIlwraith, H., Lin, J., Erdle, L., Mallos, N., Diamond, M. and Rochman, C. (2019). Capturing microfibers – marketed technologies reduce microfiber emissions from washing machines. Marine Pollution Bulletin. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.12.012

[11] Environmental Audit Committee (2019). Fixing Fashion: clothing consumption and sustainability. House of Commons. Available at: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmenvaud/1952/1952.pdf

Research and writing by Sienna Somers, Policy and Research Co-ordinator at Fashion Revolution

The world is facing a number of unprecedented and urgent environmental crises. In January 2019 the World Economic Forum released its 14th edition of the annual Global Risks Report warning that we only have 12 years to stay under 1.5°C [1]. Rising temperatures will have a profound impact on the world’s water sources, including rising sea levels, higher risk of flooding and droughts, accelerating water scarcity, pollution, disruption of freshwater systems and more.

Water crises remain within the top ten risks to society [1]. 90% of the world’s natural disasters are water-related [2]. 2 billion people live in countries exposed to high water stress – population growth, increased water demand, and climate change are likely to exacerbate this [3].

When we talk about water crises, we consider three key dimensions:

Water scarcity – the abundance, or lack thereof, of freshwater resources

Water stress – the ability, or lack thereof, to meet human and ecological demand for fresh water; compared to scarcity, “water stress” is a more inclusive and broader concept

Water risk – the possibility of an entity (community, country, company) experiencing a water-related challenge (e.g. water scarcity, water stress, flooding, infrastructure decay, drought)

Image source: CEO Water Mandate

Water is a contextual issue, being both localised and impacting fashion businesses in different ways — through company’s direct operations, supply chains and sometimes both. This makes water a highly complex and globalised problem and one that can have significant positive impacts if solved.

Water-related risks in the global apparel sector

The apparel sector is particularly vulnerable to water-related risks because water is used throughout the production of raw materials like cotton and manufacturing processes such as dyeing, tanning, printing and laundering.

Cotton is currently estimated to be the most widely used material in the apparel industry [5], making up 33% of global textile production [6]. It is a very thirsty crop, with just one pair of jeans and one t-shirt comprising one kilogram of cotton and requiring an estimated 10,000 litres of water to produce [7].

China supplies 30% of the global cotton market and manufactures a vast amount of the world’s clothing. As a result, Chinese legislation has a huge impact on both the global economy and the planet’s ecosystems. Whilst China has adopted some of the strictest regulations on heavily polluting sectors including textiles and apparel, including its 13th Five-Year Plan for Ecological & Environmental Protection (2016-2020) and the Water Pollution Prevention and Control Law [8], it remains an important country in terms of water-related risks.

India and the United States are also large cotton producing nations, where droughts are increasingly prevalent. This can impact the global market in significant ways. For example, the last major spike in the price of cotton was in 2011, where the price per pound exceeded $1.90, up 150% from early 2010 [9]. The shortage of supply was in part linked to widespread drought conditions in China and the US. These rising costs put major fashion brands and retailers in a financially tricky position. They had to make a tough choice — they could either pass on the increased cost of cotton to price-sensitive consumers or absorb the costs in their already tight profit margins, i.e. the price of the raw material went up and so everyone along the chain potentially had to shoulder that cost.

Investors want to understand how companies are addressing water-related risks

Since then, the cotton price hasn’t reached such extremes but the impact to raw material costs remains a significant risk to apparel companies. That is why investors look to understand how well companies are preparing themselves for future price shocks triggered by water-related risks, amongst other factors. Effective water management in a company’s direct operations and across its supply chain is critical, particularly as global water resources become increasingly stressed. Good water management must include board level oversight of water-related risks and thorough water risk mapping processes.

River basins are important water sources for textile and apparel suppliers and their surrounding communities. If one company happens to be polluting the water basin upstream, the downstream residents may end up drinking and bathing in polluted and unsafe water and other downstream suppliers who rely on that river basin may be negatively affected.

Fashion companies need to understand who else is using the same water supply, what forms of agriculture rely on that water supply, whether the water supply is located in a densely populated area and what communities rely on that water source for their everyday needs. This is why fashion brands and retailers must effectively assess these risks and develop holistic water management strategies and systems, covering both direct operations and supply chains – though the supply chain is even more important, given that is where the majority of the risk lies for clothing brands.

Good water management practices are key

Companies should be setting targets for improvements in water management practices, monitoring progress and disclosing the results of their efforts in consistent and comparable ways [10]. This is the only way that fashion brands and retailers will do their part towards achieving targets 6.3 [11] and 6.4 [12] of the SDGs, which aim to improve water quality, increase water-use efficiency and protect water-related ecosystems.

This article was kindly contributed for our online course, Fashion’s Future and the Sustainable Development Goals by Emma Lupton from BMO Global Asset Management. To find out more about Emma’s work, please visit the BMO website

References

- WEF. Global Risks Report 2019. 14th Edition. 2019. Available at: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Global_Risks_Report_2019.pdf

- UNISDR. The Human Cost of Weather-Related Disasters 1995-2015. 2015. Available at: https://www.unisdr.org/2015/docs/climatechange/COP21_WeatherDisastersReport_2015_FINAL.pdf

- UN Water. SDG6 Synthesis Report 2018 on Water and Sanitation. Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters. 2018. Available at: https://www.unwater.org/publications/highlights-sdg-6-synthesis-report-2018-on-water-and-sanitation-2/

- CEO. Water Mandate, Understanding Key Water Stewardship Terms. 2019. Available at: https://ceowatermandate.org/terminology/

- FAO. Profile of 15 of the world’s major plant and animal fibres. 2009. Available at: http://www.fao.org/natural-fibres-2009/about/15-natural-fibres/en/

- FAO. World Apparel Fibre Consumption Survey 2005-2008. 2011. Available at: http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/est/COMM_MARKETS_MONITORING/Cotton/Documents/World_Apparel_Fiber_Consumption_Survey_2011_-_Summary_English.pdf

- Mekonnen MM, Hoekstra AY. The green, blue and grey water footprint of crops and derived crop products. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci. 2011;15(5):1577–600.

- China Water Risk. Today’s fight for the future of fashion: Is there room for fast fashion in a Beautiful China? 2016. Available at: http://www.chinawaterrisk.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/China-Water-Risk-Brief-Todays-Fight-for-the-Future-for-the-Future-17082016-FINAL.pdf

- Financial Times. Cotton prices surge to record high amid global shortages. 2011 Feb 11. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/3d876e64-35c9-11e0-b67c-00144feabdc0

- CEO Water Mandate. Exploring the case for corporate context-based water targets. 2017. Available at: https://www.ceowatermandate.org/files/context-based-targets.pdf

- Sustainable Development Goal 6 Clean Water and Sanitation, Target 6.3; By 2030, improve water quality by reducing pollution, eliminating dumping and minimizing release of hazardous chemicals and materials, halving the proportion of untreated wastewater and substantially increasing recycling and safe reuse globally.

- Sustainable Development Goal 6 Clean Water and Sanitation, Target 6.4; By 2030, substantially increase water-use efficiency across all sectors and ensure sustainable withdrawals and supply of freshwater to address water scarcity and substantially reduce the number of people suffering from water scarcity.