The three-year anniversary of the November 24, 2012, fire that killed 112 Bangladesh garment workers at the Tazreen Fashions Ltd., factory offers a time to reflect on garment workers’ ongoing struggle for workplaces where they will not be killed or injured and for jobs that will support their families.

The Tazreen fire was preventable, as was the collapse of the multistory Rana Plaza factory five months later in which more than 1,130 garments workers died and thousands more were severely injured.

Workers at Tazreen and Rana Plaza did not have a union or other organization to represent them and help them fight for a safe workplace. Without a union, garment workers say they are harassed and even fired when they raise safety issues with their employer. They are not trained in basic fire safety measures and often their factories, like Tazreen, have locked emergency doors and stairwells packed with flammable material.

Despite the many obstacles to forming organizations and achieving a voice at work, garment workers are at the forefront of pushing for change at their factories. With our strong and long-term grassroots connections in Bangladesh, the Solidarity Center allies with garment workers to provide ongoing training for factory-level union leaders on topics such as gender equality, workers’ legal rights and fire safety.

This photo essay gives voice to the sorrow, but also the hope, of the 4 million workers who toil in Bangladesh garment factories.

1. Bangladesh’s 4 million garment workers, mostly women, toil in 5,000 factories across the country, making the $25 billion garment industry the world’s second largest, after China. Yet many risk their lives to make a living. In the three years since the fatal Tazreen Fashions Ltd. factory fire, some 31 workers have died and at least 935 people have been injured in garment factory fire incidents in Bangladesh. Credit: Law at the Margins

2. Some 112 garment workers were killed in a blaze that swept through the Tazreen factory on November 24, 2012. Hundreds more were injured and like Tahera (above), will never be able to work again. Survivors say they endure daily physical and emotional pain, and often cannot support their families because they cannot work and have received little or no compensation. Solidarity Center/Mushfique Wadud

3. Tens of thousands of Bangladesh garment workers held rallies on May Day this year to highlight the need for the freedom to form worker organizations to ensure safe and healthy workplaces. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

4. With few jobs available that pay a living wage, more than 600,000 Bangladeshi workers migrate each year. Yet, “after two years, after three years, they are not getting their salary,” says Sumaiya Islam, director of the Bangladesh Migrant Women’s Organization (BOMSA). “After spending $1,000 (to labor recruiters), they are not getting paid.” Credit: Shahjadi Zaman

5. Migrants from Bangladesh also risk their lives when going overseas for jobs. In June, Bangladesh families rallied to demand the government punish traffickers after many Bangladesh workers were among migrants stranded on abandoned boats by unscrupulous labor traffickers. “I did not get anything to eat for 22 days and just survived by eating tree leaves,” Abdur said, describing his journey to Malaysia. Credit: Solidarity Center/Mushfique Wadud

6. On April 24, 2013, the multistory Rana Plaza factory collapsed, a preventable tragedy that killed more than 1,100 garment workers and injured thousands more. On the two year anniversary in April, family members and friends gathered at the site of the building to commemorate their loss. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

7. Thousands of garment workers, like Mosammat Mukti Khatun (above, looking at the Rana Plaza rubble) who survived the Rana Plaza disaster, remain too injured or ill to work and support their families. Survivors and the families of those who lost loved ones in the collapse say they are struggling to make ends meet, unable to pay rent, send their children to school or provide for other basic needs. Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

8. Days before tens of thousands of Bangladesh garment workers rallied on the two-year anniversary of the Rana Plaza collapse, the ITUC released a report that found “a severe climate of anti-union violence and impunity prevails in Bangladesh’s garment industry. The violence is frequently directed by factory management. The government of Bangladesh has made no serious effort to bring anyone involved to account for these crimes.” Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

9. The Solidarity Center launched the Bangladesh Worker Rights Defense Fund in April 2014, following an increase in violence and harassment against workers who were seeking to form unions to protect their health and rights on the job. Donations of more than $15,500 helped to provide costly medical treatment for organizers beaten or attacked while speaking to workers about their rights, and temporary food and shelter for workers fired for trying to improve their workplace. Credit: Solidarity Center/Shawna Bader-Blau

10. Despite employer and government resistance to workers’ efforts to form organizations to improve job safety, in the Dhaka export processing zone alone, 40 of the 103 factories include workers’ welfare associations, which are similar to unions. Credit: Solidarity Center/Mushfique Wadud

11. Women garment workers primarily fuel Bangladesh’s $25 billion a year garment industry, yet women are “still viewed as basically cheap labor,” says Lily Gomes, Solidarity Center senior program officer for Bangladesh. “There is a strong need for functioning factory-level unions led by women,” says Gomes, who is leading efforts to help empower women workers to take on leadership roles at factories and in unions throughout Bangladesh. Credit: Solidarity Center/Kate Conradt

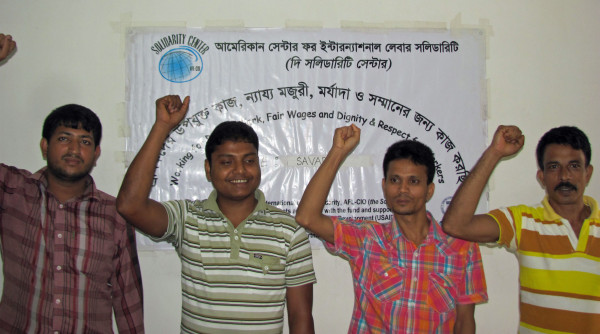

12. With strong and long-term grassroots connections in Bangladesh, the Solidarity Center provides ongoing training for garment worker union leaders on topics such as gender equality, workers’ legal rights and job safety. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

13. Garment worker union leaders sharpen their skills through regular Solidarity Center workshops, such as this one on financial management. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

14. Hundreds of garment worker union leaders have participated in this year in the Solidarity Center’s 10-week fire safety certification course. “People who worked at Tazreen and Rana Plaza had no training and had no union,” says Saiful, who took part in a recent fire training. “This training is about making sure those things never happen again.” Credit: Solidarity Center/Rakibul Hasan

Alf-Tobias Zahn interviews Anna Troupe, Head of Fashion Design and Technology at BGMEA, Bangladesh.

Alf: It is more than a pleasure having this time with you, Anna. You are new Head of the Fashion Design and Technology department at BGMEA University of Fashion and Technology. In this position you are trying to unite education with industry to advance design skills and sustainability know-how in Bangladesh. How are you connected with Fashion Revolution Day and the project Trace my Fashion?

Anna: I’m involved in Fashion Revolution Day and the Trace my Fashion project because Bangladesh’s activities for this event centered on the design students in my department and their engagement with industry sustainability leaders to learn about best practices. My role was to organize and guide them while interfacing with industry stakeholders on this initiative as a Communications Head and Strategic Partner.

“All the momentum for vital change in the garment sector is here”

Alf: How long have you been in Bangladesh – and why Bangladesh?

Anna: I’ve been here eight months and the short reason why is that all the momentum for vital change in the garment sector is here, because of Bangladesh’s significance as the second largest garments exporter and the site of the worst disaster in garment industry history.

The longer, more personal story of why I came to Bangladesh is that I entered and won a fabric design competition in 2011 that was created to support the weaving communities in the Sirajganj district of Bangladesh. Just a few months before I had very randomly discovered Muhammad Yunus’s book, Creating a World without Poverty, and decided he was my new hero and role model. After I won the fabric competition, I learned that Yunus was behind it, which was so cool because the fabric design had to symbolize “hope” and I had to include an essay explaining the symbolism. To realize that my new hero had now read my personal philosophy of hope, and liked it, really meant something to me – it felt like destiny I guess, so I took it seriously.

Then I discovered that I had just relocated to the vicinity of the top textiles program in the world, NCSU College of Textiles, so I applied to do my masters there. And within a month of starting my studies, some funding for sustainability research became available and they hired me to focus on this. But my advisor believed helping companies go green was the greater concern while I suspected that companies were jumping on the eco-friendly bandwagon to tap the “green market” while neglecting the human capital in their supply chains. Then Rana Plaza happened and settled the debate.

Meanwhile I had met Yunus at a conference he gave in North Carolina and struck up a friendship – he was very supportive and responsive to me. The day of the Rana Plaza trageday, I was in statistics class in North Carolina when I saw the news on my phone that day. The day after the collapse, I wrote Yunus, offering my condolences and asking to help and he invited me to come to Bangladesh for Social Business Day 2013. At that event I met philanthropists who appreciated what I was doing and encouraged me to return the following year. I almost didn’t do it because I’d graduated and felt the pressure to find a “real job” but luckily I came to my senses at the last minute, flew out, had delayed flights the whole way, took 4 days to arrive, missed the Social Business Day 2014 conference, but managed to connect with the philanthropists and secure funding to relocate to Dhaka and continue my research.

While visiting I learned about the need for design faculty at BUFT and was dubious because I’d never envisioned myself as a teacher. But I met with them anyway and they were so supportive and willing to let me work part-time that I decided it would be wise to get firsthand experience with the future employees of the industry I was hoping to improve. Later I lost my research funding because the donors were having to pour resources into a different project, so I made a proposal to BUFT for full-time work and they asked me to lead the department.

Alf: How many fashion students do you teach in the moment?

Anna: I currently teach 97 students myself, but there are 756 total in the department.

“We want to remove the stigma of “Made in Bangladesh”

Alf: As you said before, you have a personal relation to the Rana Plaza tragedy and a professional relation to the textile industry. You are also part of the team behind Fashion Revolution Bangladesh. Can you tell me more about the other team members and what do you want to achieve with your actions?

Anna: The country coordinator for Fashion Revolution Bangladesh this year is Bangladeshi fairtrade designer, Nawshin Khair. The larger Fashion Revolution group is a British NGO comprised of designers, academics, scientists, industry leaders, and other stakeholders. Fashion Revolution Bangladesh is currently a collaboration between BUFT, myself, Nawshin, as well as a Hong Kong-based non-profit called Lensational which provides photography training and job support to disadvantaged women such as garment workers. Fashion Revolution Bangladesh is a part of a larger consumer awareness campaign to promote better transparency and more ethical labor practices, with the specific mission to remove the stigma of “Made in Bangladesh” by highlighting the sustainability initiatives of progressive factories here.

However, Fashion Revolution Bangladesh is also a long term effort to achieve much more than that. Together we are investigating the relationship between the shortcomings in the local education system and those of the Ready-Made Garment sector, while developing training solutions to improve both, and spurring dialogue on these issues among the local and international communities that are involved. We hope to make the annual Fashion Revolution Bangladesh campaign activities a course in the BUFT fashion curriculum, as well as provide internships to students, and continue to engage industry leaders in teaching design students about sustainability, ethical practice, and compliance. We’ll also focus on gender equality in the sector by targeting female graduates specifically and informing all students about this issue.

Finally, we aim to raise the sustainability and leadership skills of Ready-Made Garment mid-level management through more advanced training programs which currently don’t exist in the country, which is why so many of these positions are held by foreigners.

Alf: Can you tell me a little bit more about the 4 case companies of your actions, especially: why have you chosen exactly these companies?

Anna: First, the companies we chose were willing to participate, which is significant because there are plenty of great progressive factories who are nevertheless skittish about shining a spotlight on what they are doing right now, especially in something that seems like an activist movement focused on the Rana Plaza disaster. Our work for next year’s event is to spend much more time in outreach, to help the industry progressives see the benefits of what we are trying to do.

Second, we chose two fairtrade and/or impact-focused firms with alternative business models as well as two mainstream factories who are producing for many big name, conventional brands, but who are regardless making great efforts to reduce environmental impact and improve the social impact.

Desh Garments was established in 1977 and was the first export-oriented Ready-Made Garment factory in Bangladesh. The import and introduction of garments technology itself is credited to Desh Garments, which in 1978 sent 130 workers and management trainees to be trained at Daewoo in South Korea. We thought introducing Desh and its journey to the students at BUFT and wider audience will help us understand how Bangladesh came to be one of the leading countries for Ready-Made Garment business.

Beximco is a vertically-integrated factory in Dhaka that supplies for major brands as well as its own local label, Yellow. In terms of work environment, it is SA8000-certified and boasts a stunning campus and facilities, including on-site medical care and childcare. So it is already setting a high standard, but we were also interested in its impressive waste management initiative: For nearly three years, it has been developing and producing upcycled clothing, or clothing that is made entirely from the scrap of other garments (pre-consumer waste), under the guidance of Aus Design, from Estonia. This is part of its dedicated sustainability department, which we wanted to highlight as an ideal for other factories to replicate.

Living Blue is a fair trade concern, where the artisans not only get a fair wage and democratically manage and run their own businesses, but also have total control over profits. The surplus generated by these various social enterprises contribute to the general well-being of local communities and help to create sustainable social, cultural and economic life.

Friendship’ Colours of the Char’ works in some of the hardest to reach areas of Bangladesh that are almost completely deprived of government or non-government amenities and facilities. These are mostly disaster prone areas comprised of inhabitants who are almost completely dependent on agricultural based livelihoods. In order to ensure constant sources of income, Friendship ‘Colours from the Chars’ provides Vocational Training Courses and alternative income generation options. It also empowers women through training and job placement at its 7 weaving centres. The fabric they make from the weaving centres uses azo-free dyes.

The above four organisations each have unique and wonderful characteristics which add to the heritage of Bangladesh. We want to communicate their stories so that there is a fuller concept behind “Made in Bangladesh.”

“Fashion would truly be a democratized and individualized art that includes and enriches all societies and our material culture”

Alf: Bangladesh is the biggest textile exporter besides China. The future of Fashion in terms of the production will be designed in Bangladesh. So, what do you think: How could the future of ethical and sustainable apparel industry look like?

Anna: This is a great question, without easy answers because the current state is so far gone, and because technological solutions, along with decreased consumption (a presumed fundamental requirement in the sustainability vision) could create massive unemployment for an uneducated labor pool if applied to the current mass-produced business model. So an entirely different approach is needed really.

My vision would be creative production clusters that are provided high-skilled and knowledgeable employees by holistic training programs and global networks in the university system (in terms of international R&D partnerships with hubs in production areas, more cultural exchange programs, and also garment-related social impact programs as a basic component of learning in university-level textiles and fashion programs). Further, these clusters would be nurtured through committed partnerships with buyers and direct relationships with individual customers who care to know the people behind their clothing.

The orgs and businesses within these clusters would value their empowered, multi-skilled workers and take responsibility for the stability and growth of their communities, through all the benefits we already know contribute to an ideal work/life balance and greater gender equality such as we see working so successfully in the Nordic countries.

The concept of mass production and multinational brands would be left behind for higher quality, custom clothing that actually represents an enduring value to the wearer because it is unique to them and required their participation in its design.

Fashion would truly be a democratized and individualized art that includes and enriches all societies and our material culture. Textiles and clothing was, for many cultures and for so much history, full of meaning and personal stories; we lost that when it became an industrialized activity, so bringing it back will help re-instate the value of the producer-artist again.

Alf: Last but not least, one more personal question: What is your favorite clothing and who made it?

Anna: My preferred clothing is vintage, second hand finds, but here in Dhaka that is no longer available to me. I try to buy from sustainable brands like Threads for Thought, Osborne Shoes, and Aus Design’s upcycled clothing, which is made right here in Dhaka at Beximco. I also want to support independent emerging designers whenever I can – Joe Mas with his label ANGEMAS out of Hong Kong is a current fav.

Alf: Thanks for your time, Anna. I wish you all the best for your work in Bangladesh and for the future of (y)our Fashion Industry!

Interview/Text: Alf-Tobias Zahn. This post first appeared in http://www.grossvrtig.de/alftobiaszahn/

Fotos: Fashion Revolution Bangladesh