During the month of February, we’ve been exploring fashion’s impact on water and looking at how we can practice water stewardship through our wardrobes. So far, we’ve discussed the consequences of industrial dyes, misconceptions around water consumption, and better laundry habits to conserve water. Now, we’re taking a look at how our wardrobes affect our oceans when they release microfibres.

What are microfibres?

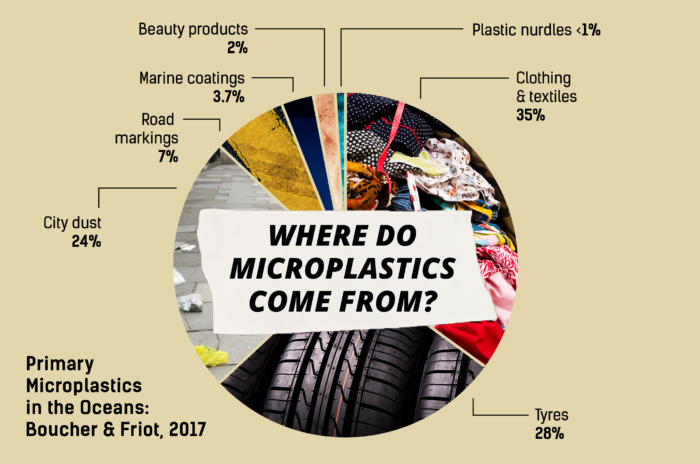

Microplastics are tiny plastic pieces that are less than <5 mm in length. Textiles are the largest source of primary microplastics (specifically manufactured to be smaller than 5mm), accounting for 34.8% of global microplastic pollution [1]. Microfibres are a type of microplastic released when we wash synthetic clothing – clothing made from plastic such as polyester and acrylic. These fibres detach from our clothes during washing and go into the wastewater. The wastewater then goes to sewage treatment facilities. As the fibres are so small, many pass through filtration processes and make their way into our rivers and seas.

Around 50% of our clothing is made from plastic [2] and up to 700,000 fibres can come off our synthetic clothes in a typical wash [3]. As a result, if the fashion industry continues as it is, between the years 2015 and 2050, 22 million tonnes of microfibres will enter our oceans [4].

What impact do microfibres have on the environment and on human health?

Due to the tiny size of microplastics, they can be ingested by marine animals which can have catastrophic effects on the species and the entire marine ecosystem.

Microfibres can absorb chemicals present in the water or sewage sludge, such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and carcinogenic Persistent Organic Pollutants (PoPs). They can also contain chemical additives, from the manufacturing phase of the materials, such as plasticisers (a substance added to improve plasticity and flexibility of a material), flame retardants and antimicrobial agents (a chemical that kills or stops the growth of microorganisms like bacteria). These chemicals can leach from the plastic into the oceans or even go straight into the bloodstream of animals that ingest the microfibres. Once ingested, microfibres can cause gut blockage, physical injury, changes to oxygen levels in cells in the body, altered feeding behaviour and reduced energy levels, which impacts growth and reproduction [5][6]. Due to this, the balance of whole ecosystems can be affected, with the impacts travelling up the food chain and sometimes making their way into the food we eat! It has been suggested that people that eat European bivalves (such as mussels, clams and oysters) can ingest over 11,000 microplastic particles per year [7].

What can fashion brands do?

The fashion industry needs to take responsibility for minimising future microfibre releases. Brands can have the most impact if they take microfibre release into consideration at the design and manufacturing stages. Designers should consider several criteria in order to minimise the environmental impact of a synthetic garment [3]:

- Use textiles which have been tested to ensure minimal release of synthetic microfibres into the environment.

- Ensure the product is durable so it remains out of landfill as long as possible

- Consider how the garment and textile waste could be recycled, to achieve a circular system.

During manufacture, there are several methods that can be applied to reduce microfibre shedding such as brushing the material, using laser and ultrasound cutting [4], coatings and pre-washing garments [1]. The length of the yarn, type of weave, and method for finishing seams may all be factors affecting shedding rates. However, much more research from brands needs to occur in order to determine best practices in reducing microfibres and create industry-wide solutions.

Waste-water treatment…

Waste-water treatment plants (where all our used water gets filtered and treated) are currently between 65-90% efficient at filtering microfibres [6]. Research and innovations into improving the efficiency of capturing microfibres in wastewater treatment plants is essential to prevent them escaping into our environment.

Washing machine filters…

Improving and developing commercial washing machine filters that can capture microfibres may allow for an additional level of filtration, whilst also educating consumers and businesses [8]. However, current filters which need to be fitted by the user, such as that developed by Wexco, are currently expensive and reportedly difficult to install. They also place a financial burden upon the consumers, rather than pressurising brands to commit to change. To tackle this, we need more industry research and legislation to ensure all new washing machines are fitted with effective filters to capture the maximum amount of microfibres possible. However, we then have the issue of what to do with the microfibres once we have caught them – an area which requires more research and industry collaboration.

Collaboration is key

Collaboration across multiple industries is required if we are to tackle microfibre pollution. In addition to material research, waste management and washing machine research and development, there is a role for other sectors such as detergent manufacturers and the recycling industry to come together to help reduce microfibre pollution. Cross-industrial agreements could help promote collaboration between industry bodies and promote sharing of resources and knowledge.

A major issue has been a lack of a standardised measure of measuring microfibre release. However, a cross-industry group, The Microfibre Consortium recently announced the first microfibre test method. The launch will enable its members (including brands, detergent manufacturers and research bodies) to accelerate research that leads to product development change and a reduction in microfibre shedding in the fashion, sport, outdoor and home textiles industries. The Microfibre Consortium also works to develop practical solutions for the textile industry to minimise microfibre release to the environment from textile manufacturing and product life cycles.

The need for microfibre legislation

Comprehensive legislative action is needed to send a strong message and force the brands to address microfibre releases from their textiles. This is a complicated issue that will require policymakers to tackle this issue on many different levels and sectors. Currently, there are no EU regulations that address microfibre release by textiles, nor are they included in the Water Framework Directive.

However, there have been several developments in microfibre legislation in the past few years:

- As of February 2020, Brune Poirson, French Secretary of State for the Ecological and Inclusive Transition, is the first politician in the world to pass microfibre legislation. As of January 2025, all new washing machines in France will have to include a filter to stop synthetic clothes from polluting our waterways. This makes France the first country in the world to take legislative steps in the fight against plastic microfibre pollution. The measure is included in the anti-waste law for a circular economy.

- In 2018, US states of California and Connecticut proposed legislation which would see polyester garments legally required to bear warning labels regarding their potential to shed microfibres during domestic washing cycles. However, this legislation is yet to be passed.

- In 2019, the EAC urged the UK government to accelerate research into the relative environmental performance of different materials, particularly with respect to measures to reduce microfibre pollution, as part of an Extended Producer Responsibility scheme. However, the UK government rejected the proposal stating that current voluntary measures are sufficient.

What can you do?

Write to your policymaker

It is vital that policy is put into place to tackle microfibres, such as the new French washing machine filter legislation. If you are concerned about microfibres, we encourage you to write to your policy representative and urge your government to take action on microfibre pollution. Now that France has enacted the microfibre legislation, it raises the bar for other governments to also take action, but they will only do so with enough pressure from the people they represent – you!

Changing your washing practices

The easiest thing you can do to minimise microfibres releasing from your clothing is to simply wash your clothes less. Given that up to 700,000 microfibres can detach in a single wash [3] ask yourself if that item really needs to be washed or can it be worn once or twice more before you do?

While some research suggested using a liquid detergent, lower washing machine temperatures, gentler washing machine settings [3] and using a front-loading washing machine [9] can reduce microfibre shedding. Researcher Imogen Napper stated they found that there was no clear evidence suggesting that changing the washing conditions gave any meaningful effect in reducing microfibre release.

You can also use a Cora Ball, a guppy bag or a self-installed washing machine filter to capture microfibres from your clothing. The CoraBall and Lint LUV-R (an install yourself washing machine filter) have been shown to reduce the number of microfibres in wastewater by an average of 26% and 87%, respectively [10]. Although these can’t solve the problem, we still want to divert as many microplastics as we can from entering our waterways.

Should we all switch from synthetic fibres?

While many people’s first instinct is to switch from synthetic materials to natural materials to minimise microfibre release, this is not always a simple choice as there are other sustainability aspects involved. The UK’s Environmental Audit Committee in their report states ‘A kneejerk switch from synthetic to natural fibres in response to the problem of ocean microfibre pollution would result in greater pressures on land and water use – given current consumption rates’ [11].

Demand brands to do more to take action on microfibres

“Ultimate responsibility for stopping this pollution, however, must lie with the companies making the products that are shedding the fibres.” states the Environmental Audit Committee [11], but there are still too many major fashion brands not taking responsibility for what happens in their supply chains and in the life cycle of their products. As well as demanding action from your policymaker, we should also ask brands what they are doing to minimize the microfibre release from their products. It is clear that there is still a lot of work to do, and as their customers, we have a lot of power in influencing the impacts of the brands we buy.

The impacts of microfibres on the environment can be mitigated, but only with systematic and meaningful change supported by policymakers, brands, industry, NGOs and citizens all working together.

References

[1] Boucher, J. and Friot, D. (2017). Primary Microplastics in the Oceans: A Global Evaluation of Sources. IUCN. Available at: https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/2017-002-En.pdf

[2] Textile Exchange (2019). Preferred Fiber and Material Market Report. Available at: https://store.textileexchange.org/wp-content/uploads/woocommerce_uploads/2019/11/Textile-Exchange_Preferred-Fiber-Material-Market-Report_2019.pdf

[3] Napper, I. and Thompson, R. (2016). Release of synthetic microplastic plastic fibres from domestic washing machines: Effects of fabric type and washing conditions. Marine Pollution Bulletin. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0025326X16307639?via%3Dihub

[4] Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2017). A new textiles economy: Redesigning fashion’s future. Available at: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/assets/downloads/publications/A-New-Textiles-Economy_Full-Report_Updated_1-12-17.pdf

[5] Koelmans, A., Bakir, A., Burton, G. and Janssen, C. (2016). Microplastic as a Vector for Chemicals in the Aquatic Environment: Critical Review and Model-Supported Reinterpretation of Empirical Studies. Environmental Science & Technology. Available at: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acs.est.5b06069

[6] Henry, B., Laitala, K. and Grimstad Klepp, I. (2018). Microplastic pollution from textiles: A literature review. Consumption Research Norway SIFO. Available at: https://www.hioa.no/eng/About-HiOA/Centre-for-Welfare-and-Labour-Research/SIFO/Publications-from-SIFO/Microplastic-pollution-from-textiles-A-literature-review

[7] Van Cauwenberghe, L. and Janssen, C. (2014). Microplastics in bivalves cultured for human consumption. Environmental Pollution. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0269749114002425

[8] Browne, M., Crump, P., Niven, S., Teuten, E., Tonkin, A., Galloway, T. and Thompson, R. (2011). Accumulation of Microplastic on Shorelines Worldwide: Sources and Sinks. Environmental Science & Technology. Available at: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/es201811s

[9] Hartline, N., Bruce, N., Karba, S., Ruff, E., Sonar, S. and Holden, P. (2016). Microfiber Masses Recovered from Conventional Machine Washing of New or Aged Garments. Environmental Science & Technology. Available at: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acs.est.6b03045

[10] McIlwraith, H., Lin, J., Erdle, L., Mallos, N., Diamond, M. and Rochman, C. (2019). Capturing microfibers – marketed technologies reduce microfiber emissions from washing machines. Marine Pollution Bulletin. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.12.012

[11] Environmental Audit Committee (2019). Fixing Fashion: clothing consumption and sustainability. House of Commons. Available at: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmenvaud/1952/1952.pdf

Research and writing by Sienna Somers, Policy and Research Co-ordinator at Fashion Revolution

At the G7 Summit, which wrapped up in Biarritz earlier this week, climate change was a central focus. On the 24th of August, just ahead of the summit, President Macron, along with 32 major fashion brands revealed the Fashion Pact, an industry wide movement aimed at aligning the fashion industry with the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

If you haven’t read the Pact, which we recommend doing, here’s what you need to know:

- The Pact is a series of commitments based on Science-Based Targets (SBTs).

- The Pact is aiming to be adopted by 20% of the global fashion industry

- The 32 signatories include:

- Adidas

- Burberry

- Chanel

- H&M

- Gap

- Inditex (Zara, Pull & Bear, Bershka, etc)

- Nike

- Nordstrom

- Prada

- Kering (Gucci, Yves St Laurent, Balenciaga, etc)

- Puma

- PVH (Calvin Klein, Tommy Hilfiger, etc)

- Stella McCartney

- The focus is on 3 pillars: Climate, Biodiversity, and Oceans

- Commitments include already existing initiatives like the UNFCCC’s Fashion Charter (of which Fashion Revolution is a signatory), alongside numerical targets like brands reaching 100% renewable energy in their own operations by 2030

Below, we hear from 3 experts across our global coordination team to find out what this Pact means for the industry, and what’s missing…

Science-Based Targets

Orsola de Castro, Co-founder: Holding fashion brands to Science-Based Targets is incredibly important for industry change. It removes the wiggle room potential of many broad and ambiguous commitments we’ve seen up until now.

Sienna Somers, Policy & Research Coordinator: SBTs for greenhouse gases are based on a given brand’s size and turnover, they must set targets to reduce their footprint in line with the 1.5-degree pathway demanded by the International Panel on Climate Change. These are pretty commonplace within the industry now and are comparable from one brand to another. However, most of the SBTs in the fashion industry are focused on the companies own operations and are not looking at the emission at the raw material level, which is where we know the majority of brands’ impact comes from. We need to see brands set targets and incentives from their raw material suppliers and through the rest of the supply chain. I am very pleased to see the addition of developing SBTs for biodiversity, this is something that is sorely needed, especially at the raw material level.

Ilishio Lovejoy, Policy & Research Manager: The Fashion Transparency Index has worked for years to push for more credible, comprehensive and comparable public disclosure of businesses’ commitments, practises and, importantly, impacts. Whilst companies setting and reporting on SBTs are necessary to ensure they are monitoring their impact and taking tangible actions to reduce their carbon emissions, if only 20% of the fashion industry is committing to net-zero, we will far exceed the 1.5 or 2-degree scenario. In contrast, the UNFCCC’s Fashion Industry Charter aims for at least 50% of the fashion industry to join, and targets not only fashion brands but media outlets, industry associations, governments and NGOs.

Collaboration over Competition

With “20% industry adoption of the Pact”, the question remains: what about everyone else?

Ilishio Lovejoy: We need to see significantly more than 20% of the global fashion industry (measured by volume of products) working together to achieve the systemic change that is necessary.

Sienna Somers: We have just eleven years left to halt irreversible climate change. However, the pact states that they (20% of the fashion industry) aim to achieve net-zero by 2050. This will be too little too late. In addition, SBTs assume everyone is essentially doing their ‘fair share’. Yet if the remaining 80% of the industry is not making progress towards tackling climate change, these actions will not be enough.

Orsola de Castro: If this 20% was made up of brands that had never made strides towards sustainability, then this would be something worth celebrating. But the fact that many of the brands, like Kering and Stella McCartney have been vocal about their environmental goals for years means that this is nothing new. Kering has been telling us they are the most sustainable luxury brand possible for the past five years, yet only now they’re signing onto these targets – what have they been doing this whole time?

Most notably missing from the list of signatories is LVMH group (Which owns Louis Vuitton, Dior, Kenzo, and dozens more luxury houses). As Kering’s biggest competitor, LVMH’s absence is a classic example of the anti-collaboration mentality that hinders sustainable innovation in the fashion industry. In a climate emergency we need collaboration over competition.

Change, NOW

While the Pact is focused on tomorrow, via its non-obligatory targets, we need action today.

Ilishio Lovejoy: The pact calls for, “Eliminating the use of single use plastics (in both B2B and B2C packaging) by 2030”. We need to see action being taken now, not by 2030. There is no longer an excuse to use virgin plastics when there are so many recycled alternatives available.

Orsola de Castro: 2030 is ridiculous – we could all be dead by then! We need a ban on single-use plastics NOW.

The Pact states, “Each member company may choose appropriate courses of action from the possibilities listed as examples below each commitment, to achieve the objectives defined in the Pact”.

Sienna Somers: Essentially, this is saying that the contents of the Pact are non-binding or non-obligatory, merely suggestions. We, as citizens, need to hold brands accountable to their commitments, otherwise, these statements, pacts and charters are simply greenwashing. We also need to demand legislation to hold these brands (and the brands doing nothing at all) to account, as this kind of non-binding protocol lets the industry-self regulate. It’s a reminder of the UK’s Environmental Audit Committee report on fashion, which pointed out that, “the fashion industry has marked its own homework for too long. Voluntary corporate social responsibility initiatives have failed significantly to improve pay and working conditions or reduce waste.”

The Elephant in the Room

Hint: It’s overproduction.

Orsola de Castro: This Pact is Copenhagen [Fashion Summit] all over again – the same people saying the same things.

Ilishio Lovejoy: We need to see more focus on the issue of overproduction as a key driver of the global climate emergency.

Orsola de Castro: Brands don’t want to talk about overproduction, but this is no longer acceptable. If we are to address climate change, fashion needs to slow down. We must divest in growth to invest in supply chain prosperity.

Sienna Somers: The bottom line is that these brands are only going to do what in their interest and what doesn’t impact profit. We need to make these issues a priority for brands and show them that if they don’t start taking action, then we will no longer support them. Once it impacts their profit, that’s when they’ll listen.

*banner image is from QUARTZY*

I was working with the Fashion Revolution team yesterday at London College of Fashion. I needed a swimsuit for my upcoming Zoology research trip to the Bahamas and heard that AURIA swimsuits were for sale at the EMG Progressive Fashion Concept Store in Beak Street, Soho, just a few blocks away. I found the perfect swimsuit! As it’s Fashion Revolution Week, I of course had to ask the question #whomademyclothes?

AURIA’s swimsuits are made from Econyl.

According to their website ‘the innovative ECONYL® Regeneration System is based on sustainable chemistry. With this process, the nylon contained in waste, such as carpets, clothing and fishing nets, is transformed back into raw material without any loss of quality.

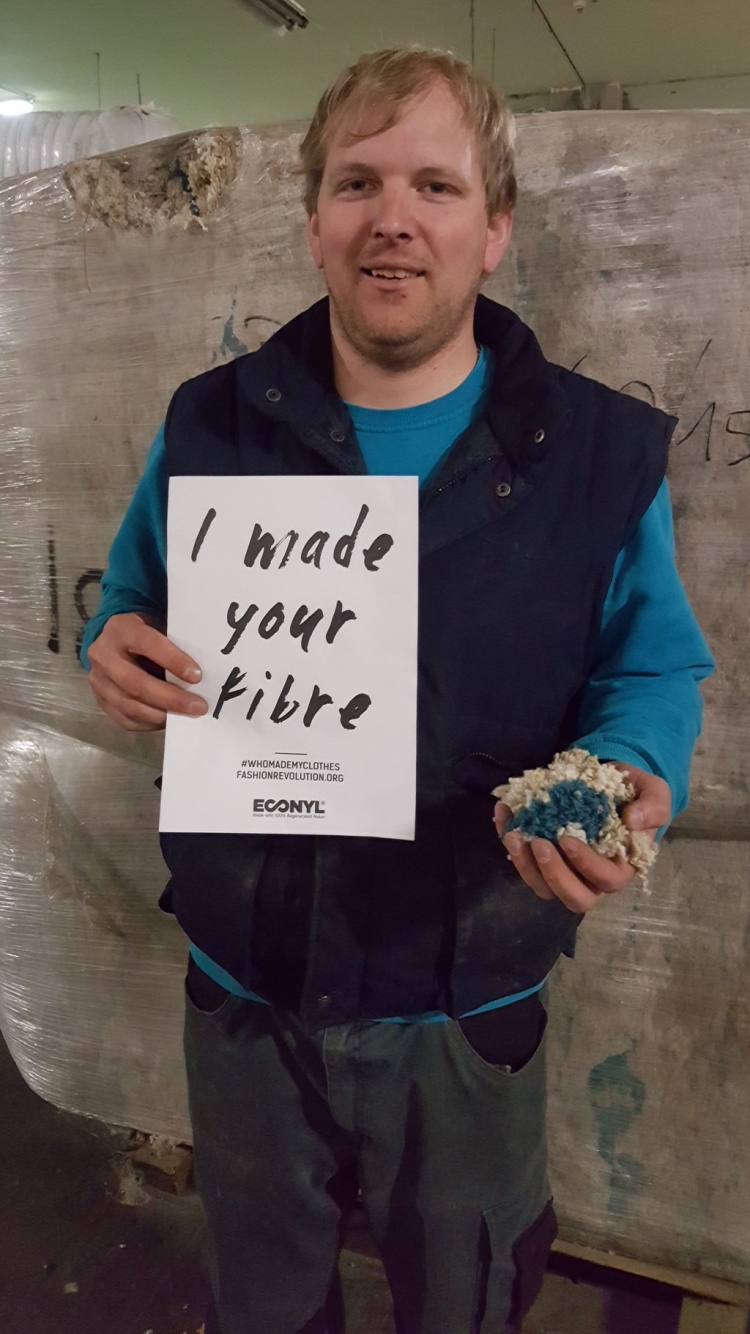

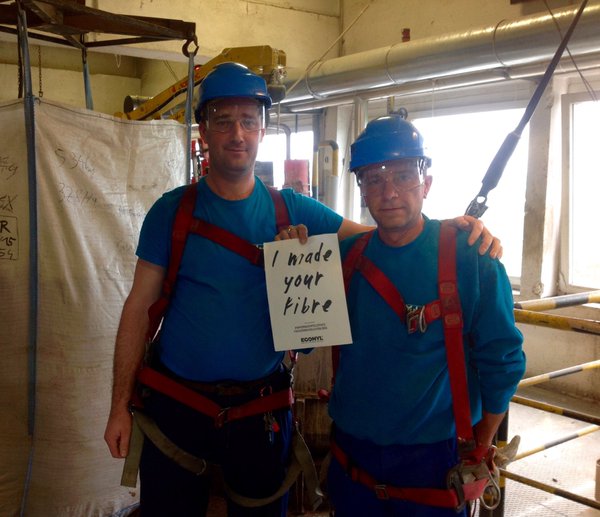

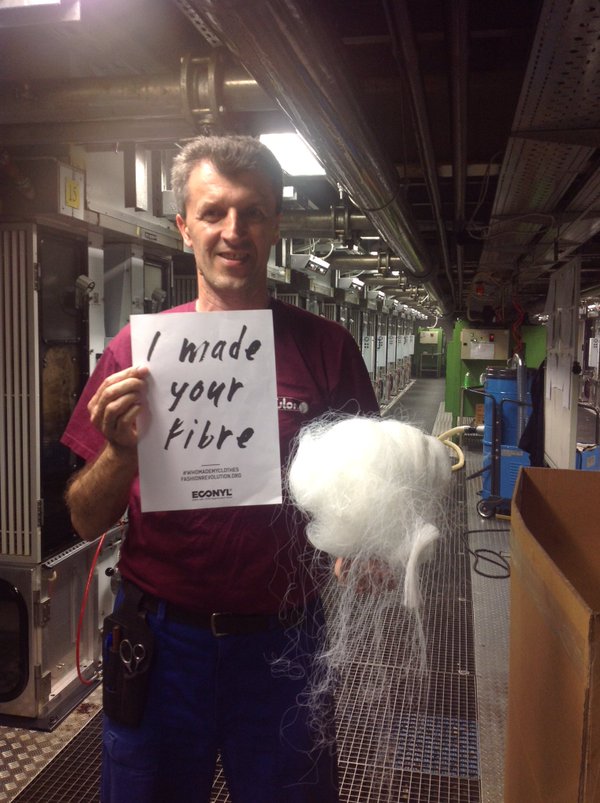

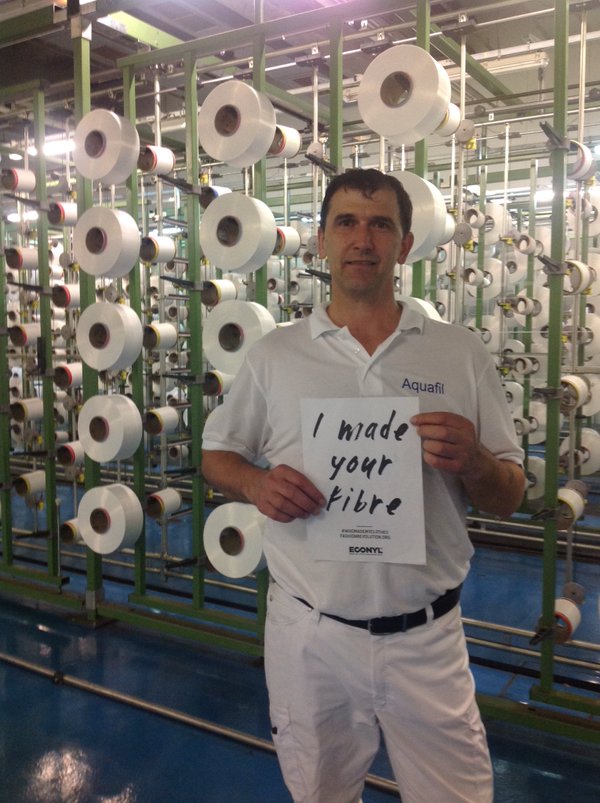

And here are the people who made my swimsuit …

This is Paolo in the ECONYL plant He prepares nets for regeneration

This is Ivo with some nets to be turned into ECONYL yarn

Jan with some carpet fluff, the upper part of old carpets that is regenerated into ECONYL yarn

Denis & Mladen they are at the very beginning of the ECONYL regeneration process

Jozica works in the chemical lab. She checks the waste material that will become ECONYL yarn

Mirko keeps an eye on the spinning to get the best quality ECONYL regenerated yarn in Slovenia

You can always find Boro around the bobbins of ECONYL regenerated yarn to check quality

Bobbins of ECONYL regenerated yarn wouldn’t get to clients if it wasn’t for Muamer

And all of this recycled fibre then gets made into gorgeous AURIA swimsuits

I’m really happy to see that ECONYL is able to answer the question #whomademyclothes and show me the faces of everyone who has helped to make the fibre for my new swimsuit #imadeyourclothes.

I’m Sienna Somers and I write a blog called The Savvy Student. This week I made a video about How to Join the Fashion Revolution.

To demonstrate how to take a selfie showing your label, I wore my favourite T-Shirt sith the slogan WE ARE THE SEA.

And then I started wondering:

Who made the T-Shirt I was wearing in the video? Where was the cotton grown? Where was it printed?

So, I decided to contact the brand, We are Islanders, and ask them #WhoMadeMyClothes? This is the fantastic reply which I have just received from Erin at We Are Islanders:

“Hi Sienna, thanks for asking! Your We Are The Sea t-shirt is from Continental Clothing’s Earth Positive Apparel collection, meaning it is 100% organic with 90% reduced CO2. The production of this t-shirt has been audited by the Fair Wear Foundation before being hand-printed by the We Are Islanders team in a Dublin print collective.”

We Are Islanders also sent me some photos of them screenprinting T-Shirts like the one I wore, so now I really do know Who Made My T-shirt!

Don’t miss my Fashion Revolution vintage #haulternative video and blog post on my website as well!