The sea. It is a sea upon which wars have been fought, across which goods and slaves have been traded, across which we have journeyed for centuries to exploit ‘new’ lands, decimate indigenous populations with our diseases and return with their treasures, and across which we are sailing today to investigate ocean plastic pollution.

The sea. Writers and poets speak of the silver sea, the lonely sea, the audacious sea, the sublime sea…. The plastic sea doesn’t have quite the same ring to it, yet that is one of the predominant qualities of the sea in this area of the South Pacific, and the reason why we are making this voyage south from Galápagos to Rapa Nui, Easter Island. We will be sailing into the South Pacific Gyre where the world’s predilection for plastic is at its most visible.

As we sail with two thousand miles of blue before us, we will experience many faces of this mercurial sea.

On our first day at sea, an hour out of harbour, we passed the meeting of currents which had split as they passed around San Cristóbal and were rejoining on the other side of the island, tracing an almost glass-like, curvilinear track between deeply furrowed verges.

CURRENT, in navigation, courans, (currens, Lat.) a certain progressive movement of the water of the sea, by which all bodies floating therein are compelled to alter their course, or velocity, or both, and submit to the laws imposed on them by the current. An Universal Dictionary of the Marine 1769. And therein lies our challenge on this voyage. How to bring velocity to a cultural current to move behaviour and habits faster around plastic pollution?

On the first night, the sea slooshed companionably against the hull and its undulating voice lulled us into the gentlest of womb-like sleeps until we are woken four hours later for our next watch. The midnight watch is my favourite. I walked up the companionway steps into a dark starscape. (No-one on board knows why a ship’s corridor is called a companionway as, on SV TravelEdge at least, it is barely wide enough for two people to pass) The moon sat like a luminous saffron saucer on the table of the horizon.

On the second night, the sea whispered conspiratorially and lured us with the glittering phosphorescence of a billion plankton. A shoal of flying fish were visible as white flashes of leaping light to starboard and the brightest of shooting stars illuminated the night sky.

On the third day we tangoed across the waves and eddies, our white ruffled line tracing a course across the deep blue dancefloor. Sea sickness set in amongst many of the crew as the sea roiled and seethed with a short swell and science was postponed in the hopes of a return to a kinder ocean tomorrow.

WAVE, a volume of water elevated by the action of the wind upon its surface, into a state of fluctuation. Definition from An Universal Dictionary of the Marine, 1769. We start asking ourselves, what are the actions we can take as a multidisciplinary crew to build momentum, to agitate, to sweep away resistance and create an unstoppable wave of change?

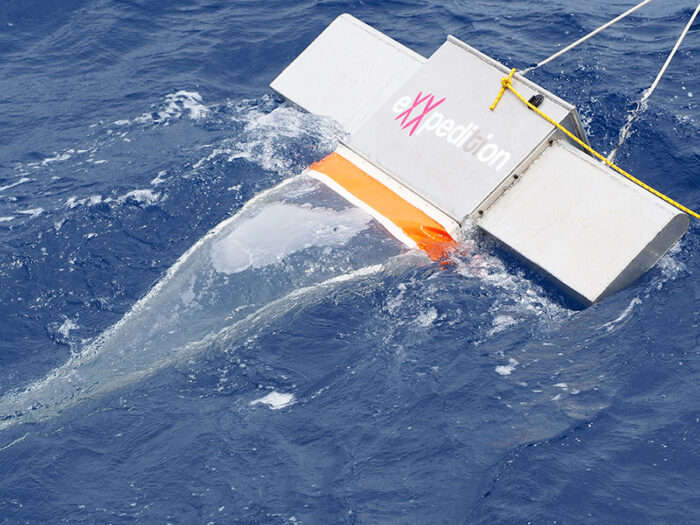

On the fourth day the swell lengthened, so we twice dropped the Manta Trawl off the spinnaker pole for half an hour each time. The contents of the trawl were passed through three sieves of increasingly fine mesh. Several Men o’ War but no visible plastic.

On the fifth day we made our first drop of the Niskin Bottle. I watched it plunge down into the unfathomable depths of the ocean, astonished by the clarity of the water as the rope extended to its full 25 feet. We whispered ‘Find the Niskin’ as we deployed the messenger weight, known on board as the golden snitch, which triggers the Niskin to close. These samples will be sent back to the lab in Plymouth to analyse how the types and quantities of microplastics in the subsurface compare to the surface water and will be the first global dataset of its kind.

On the sixth day Maggie, our first mate, hoisted metal buckets up the Mizzen mast. These will be left there for 311 nautical miles to determine whether microplastics are being transported by winds.

As the voyage continues, the wind drove us on towards our destination, with scurrying clouds and a seething sea painted a hundred hues of blue, green, grey and white. We pitch and roll. Sleep is difficult as the sheets and rigging rattle overhead and we slide into the leecloth or hull, depending on whether our bunk is port or starboard. We pass the 1000 mile mark – halfway through our voyage. Our night watch is spent creating a humorous poem about our voyage and crew based on the Beaufort Scale, which rates wind force from 0 to 12, although we have only experienced up to Force 6 to date.

Ten days into our voyage. Every mile brings us nearer to the gyre and ever trawl brings up an increasing amount of plastic: translucent filaments which coil inside our sample bottles; flecks of blue, green, white, too small for the AFTR on board so these will need to be analysed back in the lab in Plymouth; a black mesh, still pending analysis.

Thirteen days into our voyage the sea gods smile on us and the sea is almost eerily calm as we enter the South Pacifiic Gyre. We have sailed over 1700 miles and are in one of the remotest areas of the Pacific Ocean, nearing the most remote inhabited island in the world. We spend the morning and afternoon dropping the manta trawl and Niskin and analysing the results. We are shocked at what we find: our trawls within the Gyre bring up five times more microplastic, microfibres, and film than the total of all the other trawls we have carried out outside the Gyre on this voyage.

Almost every watch continues to bring its moments of awe at the sublime beauty surrounding us: the evening a school of pygmy killer whales played in our bow waves; the pinks, purples and oranges the sun paints the clouds as it sets a little later every evening on our journey south; and this morning when we saw a bright flash of rainbow suspended in a cloud at sunrise. The rainbow is a symbol of hope the world over which transcends the scientific explanation behind this regularly occurring phenomenon formed by the meeting of sunshine and water.

And herein, perhaps, lies the pathway towards finding an answer for our challenge. We need to engage people around the world in the fight to preserve the beauty and biodiversity of our oceans. We need to use the groundbreaking science we are collecting on board as a tool, but also engage people in an emotional response to the problems of plastic pollution.

A little over 200 years ago, the great explorer and scientist Alexander Von Humboldt travelled through Latin America. The Humboldt Current is named after him, an upwelling current bringing nutrients up from the deep but also bringing with it some of the tide of plastic which makes its way into the South Pacific Gyre. Humboldt’s scientific method encompassed art history, poetry and politics but in the intervening years scientists have pursued ever-narrowing areas of expertise.

The crew on board this eXXpedition voyage has been selected for our multidisciplinary set of skills and we need to work together to rediscover a multidisciplinary approach. In a world where we tend to draw a demarcation line between science and the arts, the subjective and objective, we need to reconnect science with our emotions, because we only protect what we love. I would like to think that this morning’s rainbow is nature’s way of telling us that there is hope for our oceans if we can find ways to make people around the world fall back in love with the science and poetry of this boundless deep blue sea.

Plastic is designed to last forever, but we are using it to design products, including clothing and its related packaging, that are only used once. Around two thirds of our clothes are made from synthetic fibres, such as polyester, acrylic and nylon, which are all plastics. The process of turning fossil fuels into textiles for our clothes releases significant amounts of Greenhouse Gases.

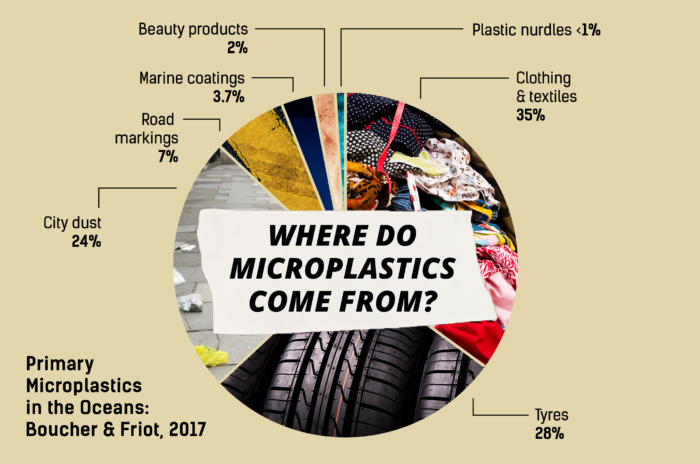

Fashion’s impact on the environment doesn’t stop once our clothes are made. Textiles are the largest source of both primary and secondary microplastics, accounting for 34.8% of global microplastic pollution1, with around 700,000 microfibres being released in every wash cycle2. These microfibres enter our sewage system and many are too small to be collected by the wastewater treatment plants. Even those microfibres which are captured can end up in our oceans as treatment plant sludge is frequently used as a fertiliser on fields, from which it enters waterways and, in the end, the sea.

It has been estimated that 1.4 million trillion microfibres are currently in the oceans3 and if the fashion industry continues in a business-as-usual scenario, between 2015 and 2050, 22 million tonnes of microfibres will enter our oceans4. Recent research shows that plastics emit powerful greenhouse gases as they degrade and, over time, give off more and more gas, so the plastics accumulating in our oceans represent a vast, uncontrollable source of future emissions, as well as posing a danger to our marine ecosystems and to human health.

The fourth edition of Fashion Revolution’s Fashion Transparency Index, launched in April 2019, ranks 200 of the world’s largest fashion brands and retailers according to their level of transparency. It measures how much information brands disclose about their suppliers, supply chain policies and practices, and social and environmental impacts. In April 2020, the fifth edition will be published, covering 250 brands and retailers. Five key areas are assessed: Policy & Commitments, Governance, Traceability, Know, Show & Fix which looks at how brands assess their suppliers and how they work to fix any problems and Spotlight Issues, which in 2019 focused on the the SDGs, the Sustainable Development Goals.

In terms of SDG12 Responsible Production and Consumption, whilst 43% of brands are publishing a sustainable materials strategy or roadmap, only 29% are disclosing the percentage of their products that are made from sustainable materials and just 15% publish measurable, timebound targets for the reduction of virgin plastics. Only 26% of brands explain how they are investing in circular solutions to reduce textile waste. In our 2020 Index, one of our Spotlight Issues will be Composition, looking at how brands and retailers are reducing salient environmental risks through material selection, the elimination of hazardous chemicals and moving towards circularity. As part of this section, we will be looking for disclosure on what the brands are doing to minimise the impact of microfibres.

As we sail from Galápagos to Easter Island with eXXpedition, the analysis of polymer types from the plastics we collect will be invaluable for those brands who are committed to acting to reduce microfibre shedding and microplastics in our environment as they will be able to better understand the density and distribution in the oceans of the different plastic fibres found in our clothing so they can prioritise actions to reduce the areas of greatest impact.

However, there are no simple solutions when it comes to materials. A polyester shirt can have more than double the carbon footprint of a cotton shirt, but synthetic fibres generally have less impact on water and land than cotton5. Synthetic fibres made from recycled materials such as crushed plastic bottles or reclaimed fishing nets have around 50% lower emissions than using virgin fossil fuels6 but the microfibre release is likely to be the same.

Building a more sustainable fashion industry and curbing its destructive impact on our oceans will entail governments, brands, retailers and citizens all taking action together to help bring about the systemic change needed to end the exploitation of our planet.

Governments must act urgently to deal with fashion’s escalating environmental problem and as these solutions will, in turn, help tackle climate change, this should be a win-win. We are currently allowing companies to evade responsibility for their environmental impacts, so we also need to see mandatory due diligence and reporting for all major brands and retailers. Legislation should also be passed requiring all new washing machines to be fitted with effective filters to ensure maximum capture of microfibres.

Brands and retailers must change their business models and create products with longevity and quality. They must understand the true value of materials, which should be mindfully designed, redesigned and recuperated as a valuable resource. Brands must set Science-Based Targets and report annually on their progress. And they must use sustainability to drive all aspects of their business.

It can be hard to know how best to care for our clothes as research on reducing microfibre shedding is limited and, at times, contradictory. Recent advice suggests short cycles, using liquid detergent and fabric softener and washing at a low temperature. What is certain is that the best way to reduce microfibre shedding is to wash our clothes less frequently. We can also rethink the fibres in our wardrobe and choose wisely when buying new clothes.

Finally, we can all use our voice and our power to demand that brands and legislators work to reduce the trillions of microfibres flooding into our waterways. That’s why Fashion Revolution has just launched a new hashtag #WhatsInMyClothes.

Fashion Revolution’s Manifesto states, “Fashion conserves and restores the environment. It does not deplete precious resources, degrade our soil, pollute our air and water, or harm our health. Fashion protects the welfare of all living things and safeguards our diverse ecosystems”. If we all work together, we can, and must, create a global fashion industry that conserves and restores the environment and values the wellbeing of everyone and everything living on this earth and in our oceans over growth and profit.

[1] Boucher and Friot, 2017

[2] Napper and Thompson, 2016

[3] Leonard, 2016

[4] Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017

[5] Olivetti et al., 2015

[6] Textile Exchange, 2017

During the month of February, we’ve been exploring fashion’s impact on water and looking at how we can practice water stewardship through our wardrobes. So far, we’ve discussed the consequences of industrial dyes, misconceptions around water consumption, and better laundry habits to conserve water. Now, we’re taking a look at how our wardrobes affect our oceans when they release microfibres.

What are microfibres?

Microplastics are tiny plastic pieces that are less than <5 mm in length. Textiles are the largest source of primary microplastics (specifically manufactured to be smaller than 5mm), accounting for 34.8% of global microplastic pollution [1]. Microfibres are a type of microplastic released when we wash synthetic clothing – clothing made from plastic such as polyester and acrylic. These fibres detach from our clothes during washing and go into the wastewater. The wastewater then goes to sewage treatment facilities. As the fibres are so small, many pass through filtration processes and make their way into our rivers and seas.

Around 50% of our clothing is made from plastic [2] and up to 700,000 fibres can come off our synthetic clothes in a typical wash [3]. As a result, if the fashion industry continues as it is, between the years 2015 and 2050, 22 million tonnes of microfibres will enter our oceans [4].

What impact do microfibres have on the environment and on human health?

Due to the tiny size of microplastics, they can be ingested by marine animals which can have catastrophic effects on the species and the entire marine ecosystem.

Microfibres can absorb chemicals present in the water or sewage sludge, such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and carcinogenic Persistent Organic Pollutants (PoPs). They can also contain chemical additives, from the manufacturing phase of the materials, such as plasticisers (a substance added to improve plasticity and flexibility of a material), flame retardants and antimicrobial agents (a chemical that kills or stops the growth of microorganisms like bacteria). These chemicals can leach from the plastic into the oceans or even go straight into the bloodstream of animals that ingest the microfibres. Once ingested, microfibres can cause gut blockage, physical injury, changes to oxygen levels in cells in the body, altered feeding behaviour and reduced energy levels, which impacts growth and reproduction [5][6]. Due to this, the balance of whole ecosystems can be affected, with the impacts travelling up the food chain and sometimes making their way into the food we eat! It has been suggested that people that eat European bivalves (such as mussels, clams and oysters) can ingest over 11,000 microplastic particles per year [7].

What can fashion brands do?

The fashion industry needs to take responsibility for minimising future microfibre releases. Brands can have the most impact if they take microfibre release into consideration at the design and manufacturing stages. Designers should consider several criteria in order to minimise the environmental impact of a synthetic garment [3]:

- Use textiles which have been tested to ensure minimal release of synthetic microfibres into the environment.

- Ensure the product is durable so it remains out of landfill as long as possible

- Consider how the garment and textile waste could be recycled, to achieve a circular system.

During manufacture, there are several methods that can be applied to reduce microfibre shedding such as brushing the material, using laser and ultrasound cutting [4], coatings and pre-washing garments [1]. The length of the yarn, type of weave, and method for finishing seams may all be factors affecting shedding rates. However, much more research from brands needs to occur in order to determine best practices in reducing microfibres and create industry-wide solutions.

Waste-water treatment…

Waste-water treatment plants (where all our used water gets filtered and treated) are currently between 65-90% efficient at filtering microfibres [6]. Research and innovations into improving the efficiency of capturing microfibres in wastewater treatment plants is essential to prevent them escaping into our environment.

Washing machine filters…

Improving and developing commercial washing machine filters that can capture microfibres may allow for an additional level of filtration, whilst also educating consumers and businesses [8]. However, current filters which need to be fitted by the user, such as that developed by Wexco, are currently expensive and reportedly difficult to install. They also place a financial burden upon the consumers, rather than pressurising brands to commit to change. To tackle this, we need more industry research and legislation to ensure all new washing machines are fitted with effective filters to capture the maximum amount of microfibres possible. However, we then have the issue of what to do with the microfibres once we have caught them – an area which requires more research and industry collaboration.

Collaboration is key

Collaboration across multiple industries is required if we are to tackle microfibre pollution. In addition to material research, waste management and washing machine research and development, there is a role for other sectors such as detergent manufacturers and the recycling industry to come together to help reduce microfibre pollution. Cross-industrial agreements could help promote collaboration between industry bodies and promote sharing of resources and knowledge.

A major issue has been a lack of a standardised measure of measuring microfibre release. However, a cross-industry group, The Microfibre Consortium recently announced the first microfibre test method. The launch will enable its members (including brands, detergent manufacturers and research bodies) to accelerate research that leads to product development change and a reduction in microfibre shedding in the fashion, sport, outdoor and home textiles industries. The Microfibre Consortium also works to develop practical solutions for the textile industry to minimise microfibre release to the environment from textile manufacturing and product life cycles.

The need for microfibre legislation

Comprehensive legislative action is needed to send a strong message and force the brands to address microfibre releases from their textiles. This is a complicated issue that will require policymakers to tackle this issue on many different levels and sectors. Currently, there are no EU regulations that address microfibre release by textiles, nor are they included in the Water Framework Directive.

However, there have been several developments in microfibre legislation in the past few years:

- As of February 2020, Brune Poirson, French Secretary of State for the Ecological and Inclusive Transition, is the first politician in the world to pass microfibre legislation. As of January 2025, all new washing machines in France will have to include a filter to stop synthetic clothes from polluting our waterways. This makes France the first country in the world to take legislative steps in the fight against plastic microfibre pollution. The measure is included in the anti-waste law for a circular economy.

- In 2018, US states of California and Connecticut proposed legislation which would see polyester garments legally required to bear warning labels regarding their potential to shed microfibres during domestic washing cycles. However, this legislation is yet to be passed.

- In 2019, the EAC urged the UK government to accelerate research into the relative environmental performance of different materials, particularly with respect to measures to reduce microfibre pollution, as part of an Extended Producer Responsibility scheme. However, the UK government rejected the proposal stating that current voluntary measures are sufficient.

What can you do?

Write to your policymaker

It is vital that policy is put into place to tackle microfibres, such as the new French washing machine filter legislation. If you are concerned about microfibres, we encourage you to write to your policy representative and urge your government to take action on microfibre pollution. Now that France has enacted the microfibre legislation, it raises the bar for other governments to also take action, but they will only do so with enough pressure from the people they represent – you!

Changing your washing practices

The easiest thing you can do to minimise microfibres releasing from your clothing is to simply wash your clothes less. Given that up to 700,000 microfibres can detach in a single wash [3] ask yourself if that item really needs to be washed or can it be worn once or twice more before you do?

While some research suggested using a liquid detergent, lower washing machine temperatures, gentler washing machine settings [3] and using a front-loading washing machine [9] can reduce microfibre shedding. Researcher Imogen Napper stated they found that there was no clear evidence suggesting that changing the washing conditions gave any meaningful effect in reducing microfibre release.

You can also use a Cora Ball, a guppy bag or a self-installed washing machine filter to capture microfibres from your clothing. The CoraBall and Lint LUV-R (an install yourself washing machine filter) have been shown to reduce the number of microfibres in wastewater by an average of 26% and 87%, respectively [10]. Although these can’t solve the problem, we still want to divert as many microplastics as we can from entering our waterways.

Should we all switch from synthetic fibres?

While many people’s first instinct is to switch from synthetic materials to natural materials to minimise microfibre release, this is not always a simple choice as there are other sustainability aspects involved. The UK’s Environmental Audit Committee in their report states ‘A kneejerk switch from synthetic to natural fibres in response to the problem of ocean microfibre pollution would result in greater pressures on land and water use – given current consumption rates’ [11].

Demand brands to do more to take action on microfibres

“Ultimate responsibility for stopping this pollution, however, must lie with the companies making the products that are shedding the fibres.” states the Environmental Audit Committee [11], but there are still too many major fashion brands not taking responsibility for what happens in their supply chains and in the life cycle of their products. As well as demanding action from your policymaker, we should also ask brands what they are doing to minimize the microfibre release from their products. It is clear that there is still a lot of work to do, and as their customers, we have a lot of power in influencing the impacts of the brands we buy.

The impacts of microfibres on the environment can be mitigated, but only with systematic and meaningful change supported by policymakers, brands, industry, NGOs and citizens all working together.

References

[1] Boucher, J. and Friot, D. (2017). Primary Microplastics in the Oceans: A Global Evaluation of Sources. IUCN. Available at: https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/2017-002-En.pdf

[2] Textile Exchange (2019). Preferred Fiber and Material Market Report. Available at: https://store.textileexchange.org/wp-content/uploads/woocommerce_uploads/2019/11/Textile-Exchange_Preferred-Fiber-Material-Market-Report_2019.pdf

[3] Napper, I. and Thompson, R. (2016). Release of synthetic microplastic plastic fibres from domestic washing machines: Effects of fabric type and washing conditions. Marine Pollution Bulletin. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0025326X16307639?via%3Dihub

[4] Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2017). A new textiles economy: Redesigning fashion’s future. Available at: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/assets/downloads/publications/A-New-Textiles-Economy_Full-Report_Updated_1-12-17.pdf

[5] Koelmans, A., Bakir, A., Burton, G. and Janssen, C. (2016). Microplastic as a Vector for Chemicals in the Aquatic Environment: Critical Review and Model-Supported Reinterpretation of Empirical Studies. Environmental Science & Technology. Available at: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acs.est.5b06069

[6] Henry, B., Laitala, K. and Grimstad Klepp, I. (2018). Microplastic pollution from textiles: A literature review. Consumption Research Norway SIFO. Available at: https://www.hioa.no/eng/About-HiOA/Centre-for-Welfare-and-Labour-Research/SIFO/Publications-from-SIFO/Microplastic-pollution-from-textiles-A-literature-review

[7] Van Cauwenberghe, L. and Janssen, C. (2014). Microplastics in bivalves cultured for human consumption. Environmental Pollution. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0269749114002425

[8] Browne, M., Crump, P., Niven, S., Teuten, E., Tonkin, A., Galloway, T. and Thompson, R. (2011). Accumulation of Microplastic on Shorelines Worldwide: Sources and Sinks. Environmental Science & Technology. Available at: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/es201811s

[9] Hartline, N., Bruce, N., Karba, S., Ruff, E., Sonar, S. and Holden, P. (2016). Microfiber Masses Recovered from Conventional Machine Washing of New or Aged Garments. Environmental Science & Technology. Available at: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acs.est.6b03045

[10] McIlwraith, H., Lin, J., Erdle, L., Mallos, N., Diamond, M. and Rochman, C. (2019). Capturing microfibers – marketed technologies reduce microfiber emissions from washing machines. Marine Pollution Bulletin. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.12.012

[11] Environmental Audit Committee (2019). Fixing Fashion: clothing consumption and sustainability. House of Commons. Available at: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmenvaud/1952/1952.pdf

Research and writing by Sienna Somers, Policy and Research Co-ordinator at Fashion Revolution

There are three things I have been passionate about over the course of my life: sailing and the sea, the indigenous cultures of South and Central America, and creating a more sustainable fashion industry.

Working with Pachacuti, the hat brand I founded over two decades ago, and at Fashion Revolution over the past six years, has brought together the latter two areas in many ways, but now I am incredibly excited to be able to draw all three of these strands together. In February and March 2020, I will be setting sail with eXXpedition to investigate plastic pollution and toxics in our oceans. Almost 10,000 women from around the world applied to take part in the two year voyage and I feel incredibly fortunate to have been selected to crew on the leg from the Galapagos to Easter Island.

I learnt to sale on the magnificent J-Class yacht Velsheda in the late ’80s and spent a few summers as crew before jumping over to the square rigged brig TS Astrid on which I spent many happy months sailing the Channel and taking part in the Tall Ships Race. I then worked on various boats in the Caribbean for a year and sailed across the Atlantic on the tops’l schooner TS Unicorn. I remember night after night on the seemingly pristine sea watching the glowing, glittering phosphorescence resulting from the bioluminescence of organisms in the surface layers of the sea (we took two months crossing the Atlantic so there were plenty of sea sparkle nights to enjoy!) I never imagined that I would be sailing the oceans again three decades later to carry out research into the degradation of the marine environment.

My Masters in Native American Studies at the University of Essex was the culmination of an interest in the Andean region which stemmed from somewhere far back in my childhood – I remember asking for a picture book about the Incas as a Christmas present one year when I was still quite young. I immersed myself in learning about indigenous cultures past and present and would have continued with my PhD on the symbolism of colour and natural dyes in the Andes. However, having set up Pachacuti in the summer holidays and seen at first hand the real difference fair trade could make to textile-producing communities in Ecuador, I decided to turn my interest in the region to more practical use.

One of the key concepts of the Andean worldview is ayni, meaning reciprocity and balance. Balance does not mean just a static equibrium; the Inca strived for the creation of an animated cosmos through a system of continual exchange based on mutual respect, justice, and solidarity. They saw reciprocity as the foundation for peace, resilience and enduring relationships with our environment and our community both near and far. Ayni was a continuous accompaniment to life in the Andes and the foundation on which society was based. Indeed, life itself can be seen as ayni.

If the equilibrium between communities and the natural world was altered, it could result in floods, or lack of rains. Andean peoples understood that ayni has to be recreated every day in order for regeneration to take place and, as a result, knew that they needed to give things up, to make sacrifices to restore balance. Reciprocity moves people beyond self interest in order to do something for the common good.

Perhaps it is not surprising that in 2008, Ecuador became the first country to legally recognise the rights of nature and two years later Bolivia adopted the Law of the Rights of Mother Earth. This means in practice that people can now sue on behalf of the ecosystem. The Ecuadorian Constitution says this will help to “achieve the good way of living, the sumac kawsay.” Nature is part of the social fabric of life, not a resource to be exploited. The Andean concept of good living or living well doesn’t mean living better than others, nor does it imply the accumulation of material wealth. It means living well together, with nature, with mutual support, with ayni.

I was reminded of this whilst on holiday this summer, in a chalet by the sea on Branscombe beach in Devon. I was working there with my daughter, Sienna, and we were discussing stakeholders for Fashion Revolution’s policy dialogue toolkits. She told me that we must make sure we include stakeholders who don’t have a voice like the ocean and marine life. It seemed so obvious once she said it and I was astonished I had never previously thought of including them. This just emphasised to me how far we have become detached from seeing our world as a living being.

Reciprocity is inherent in the way the earth works, although there are limits that are difficult to reverse once they are crossed, as set out in the UN United in Science report issued on 22 September. Our activities, our pollution, our degradation of the marine environment are stressing the earth’s natural capacity for reciprocity. If we are to tackle toxics and plastic pollution in our oceans, as well as climate change, waste, and the myriad other environmental issues relating to the fashion industry, we know that every choice and every action matters. If we want to see regeneration of our waterways and oceans which are essential for living well on this planet together, we need to take co-operative responsibility. The resources of both land and sea are a gift, and this gift requires reciprocity in order to maintain healthy ecosystems.

When I join eXXpedition and sail some 2000 miles through the Pacific Ocean, I will be taking part in groundbreaking scientific research on board this floating laboratory to help build a comprehensive picture of the state of our seas. I will also be helping to unravel how we got into this mess and how we can help shift our mindsets towards a more sustainable, a more balanced, future which encourages progress to a more regenerative system. The worldview of the peoples who inhabit the countries past which I will be sailing may well help us to find some of these solutions.

***

The eXXpedition Round the World voyage, which sets sail from Plymouth, UK on October 8th 2019, will sail through some of the most important and diverse marine environments on the planet. This includes crossing four of the five oceanic gyres, where ocean plastic is known to accumulate, and the Arctic on board 73ft sailing vessel S.V. TravelEdge. Under the directorship of award winning ocean advocate Emily Penn, 300 women will join the research vessel as crew over 30 voyage legs to journey more than 38,000 nautical miles. Follow news and updates via #eXXpedition @exxpedition on Twitter / @exxpedition_ on Instagram /eXXpedition on Facebook

I am looking for sponsorship and donations towards my participation in this groundbreaking voyage. Please see more information here – I am very grateful for any support.

Header photo: Soraya Abdel Hadi/eXXpedition

With the recent publicity around sustainable oriented fashion new year resolutions we’re revisiting this article centred around ASOS’s announcement to ban all feathers, silk mohair and cashmere last year. The article raises the point that whilst praise should be given to those re considering the attitude towards fashion and their wardrobes, blanket statements towards your future habits are not always the best form of action. We encourage you to think, question and research solutions to your current less favourable buying habits. Moving to sustainable fashion is step in the right direction, however the term is broad, only through research and transparency can we separate the brands genuinely looking to install good practices at every level of the supply chain from those just making a token gesture towards improving practices.

The recent announcement from ASOS that they will be banning all feathers, silk, mohair and cashmere has started a social media furore, quite rightly. Not because the ban in itself is a mistake – it shows that they are indeed taking into account their customers’ concerns in regards to animal welfare; concerns that our insatiable desire for soft, fluffy and silky materials poses a real threat to animals and their environment. The controversy arises from our suspicions that this new policy will not introduce better solutions to replace unethical, environmentally-unfriendly fabrics.

ASOS will need to replace those products with other equally soft, silky and fluffy materials and, inevitably, the fear is that the alternative will increase the production of fabrics made from plastic-based fibres such as polyester which are potentially just as bad, if not more harmful to the natural world and the animals living in it in the long run. And therein lies the contradiction: in order not to harm goats, geese, ducks and silk worms, the risk is that other forms of life, including us, will be harmed in the process. Instead of a blanket ban on these materials, should ASOS instead have focused on innovation and responsible sourcing, such as using Peace Silk or ensuring feathers are sourced under the Responsible Down Standard guidelines?

Polyester is pure plastic, it takes an estimated 1000 years to decompose. It releases microfibres which can enter the bloodstream of marine species, causing reproductive and growth issues and when ingested they cause species to think they are full and consequently become malnourished. Moreover, they can can enter human bodies when we consume shellfish, with currently unknown consequences. It has been estimated that 1.4 million trillion microfibres are currently in the oceans (Leonard, 2016), with some regions releasing up to 281 kilotonnes of primary microplastics per year (Boucher and Friot, 2017). If the fashion industry continues in a business-as-usual scenario, between 2015 and 2050 22 million tonnes of microfibres will enter our oceans (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017).

The fact that polyester is recyclable in circular, closed loop systems is not an excuse because we are still far from having an industry capable of recycling its plastic successfully enough not to produce more plastic overall. We are on the road to circularity, but we are not there yet.

We are nowhere near an industry where materials are recycled or downcycled in a clean, non-toxic, efficient way. The technology to recycle mixed blends such as cotton and poly still requires further injections of polyester to increase quality and functionality and blended fabrics cannot yet be commercially separated at scale in order to recycle the different fibres.

Even biodegradable materials are not completely harmless. Organic waste decomposing in landfill is one of the biggest contributors of atmospheric methane. At the moment, we really are stuck between a rock and a hard place.

The debate over ASOS’s announcement is possible because there is now enough information on the negative effects of plastic on our environment. Not enough was done by ASOS to consider the reaction of a better educated audience and not enough reassurances were given on what alternative materials will be used instead. This announcement did look a lot like a nod to the growing animal welfare lobby, rather than a well thought out strategy leading to real and radical changes for the better. Is this a convenient excuse to divert from costly fibres and replace with synthetic alternatives in the name of ethical progress?

The announcement may prove that ASOS, like other brands, are listening but it also shows that they don’t necessarily know where they are going because right now nothing has a simple solution; almost every step comes accompanied by a fair amount of inevitable contradictions.

It won’t be easy or quick to steer these gigantic ships, to change our habits and theirs in favour of fully sustainable alternatives. Of course, the entire fashion industry needs to speed up and adopt better social and environmental practices throughout its complicated, ineffective and exploitative supply chain and what we can keep doing is encouraging debate and dialogue. Be vigilant, scrutinise, keep asking questions. This at least will show brands that we won’t be satisfied by half measures and unresolved solutions. That we expect real change because we want to wear clothes that make us feel good – and exploitation and resource depletion are definitely not a good look.

Photo credits:

Clothing sorted for recycling, Buenos Aires, Carry Somers

Ocean: Ross Miller