Plastic is designed to last forever, but we are using it to design products, including clothing and its related packaging, that are only used once. Around two thirds of our clothes are made from synthetic fibres, such as polyester, acrylic and nylon, which are all plastics. The process of turning fossil fuels into textiles for our clothes releases significant amounts of Greenhouse Gases.

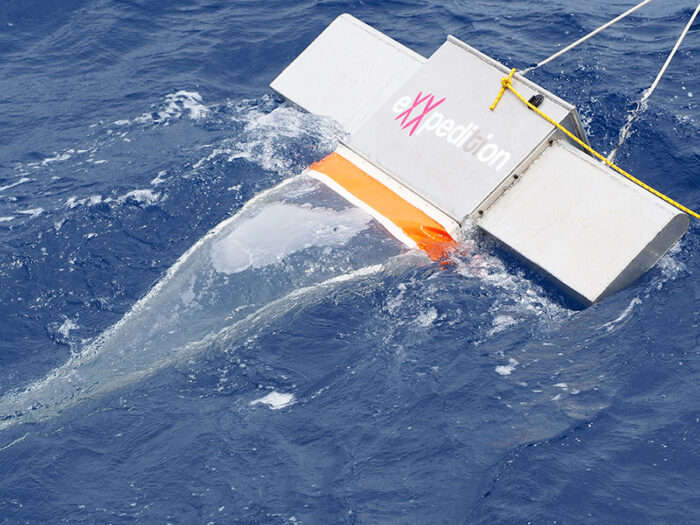

Fashion’s impact on the environment doesn’t stop once our clothes are made. Textiles are the largest source of both primary and secondary microplastics, accounting for 34.8% of global microplastic pollution1, with around 700,000 microfibres being released in every wash cycle2. These microfibres enter our sewage system and many are too small to be collected by the wastewater treatment plants. Even those microfibres which are captured can end up in our oceans as treatment plant sludge is frequently used as a fertiliser on fields, from which it enters waterways and, in the end, the sea.

It has been estimated that 1.4 million trillion microfibres are currently in the oceans3 and if the fashion industry continues in a business-as-usual scenario, between 2015 and 2050, 22 million tonnes of microfibres will enter our oceans4. Recent research shows that plastics emit powerful greenhouse gases as they degrade and, over time, give off more and more gas, so the plastics accumulating in our oceans represent a vast, uncontrollable source of future emissions, as well as posing a danger to our marine ecosystems and to human health.

The fourth edition of Fashion Revolution’s Fashion Transparency Index, launched in April 2019, ranks 200 of the world’s largest fashion brands and retailers according to their level of transparency. It measures how much information brands disclose about their suppliers, supply chain policies and practices, and social and environmental impacts. In April 2020, the fifth edition will be published, covering 250 brands and retailers. Five key areas are assessed: Policy & Commitments, Governance, Traceability, Know, Show & Fix which looks at how brands assess their suppliers and how they work to fix any problems and Spotlight Issues, which in 2019 focused on the the SDGs, the Sustainable Development Goals.

In terms of SDG12 Responsible Production and Consumption, whilst 43% of brands are publishing a sustainable materials strategy or roadmap, only 29% are disclosing the percentage of their products that are made from sustainable materials and just 15% publish measurable, timebound targets for the reduction of virgin plastics. Only 26% of brands explain how they are investing in circular solutions to reduce textile waste. In our 2020 Index, one of our Spotlight Issues will be Composition, looking at how brands and retailers are reducing salient environmental risks through material selection, the elimination of hazardous chemicals and moving towards circularity. As part of this section, we will be looking for disclosure on what the brands are doing to minimise the impact of microfibres.

As we sail from Galápagos to Easter Island with eXXpedition, the analysis of polymer types from the plastics we collect will be invaluable for those brands who are committed to acting to reduce microfibre shedding and microplastics in our environment as they will be able to better understand the density and distribution in the oceans of the different plastic fibres found in our clothing so they can prioritise actions to reduce the areas of greatest impact.

However, there are no simple solutions when it comes to materials. A polyester shirt can have more than double the carbon footprint of a cotton shirt, but synthetic fibres generally have less impact on water and land than cotton5. Synthetic fibres made from recycled materials such as crushed plastic bottles or reclaimed fishing nets have around 50% lower emissions than using virgin fossil fuels6 but the microfibre release is likely to be the same.

Building a more sustainable fashion industry and curbing its destructive impact on our oceans will entail governments, brands, retailers and citizens all taking action together to help bring about the systemic change needed to end the exploitation of our planet.

Governments must act urgently to deal with fashion’s escalating environmental problem and as these solutions will, in turn, help tackle climate change, this should be a win-win. We are currently allowing companies to evade responsibility for their environmental impacts, so we also need to see mandatory due diligence and reporting for all major brands and retailers. Legislation should also be passed requiring all new washing machines to be fitted with effective filters to ensure maximum capture of microfibres.

Brands and retailers must change their business models and create products with longevity and quality. They must understand the true value of materials, which should be mindfully designed, redesigned and recuperated as a valuable resource. Brands must set Science-Based Targets and report annually on their progress. And they must use sustainability to drive all aspects of their business.

It can be hard to know how best to care for our clothes as research on reducing microfibre shedding is limited and, at times, contradictory. Recent advice suggests short cycles, using liquid detergent and fabric softener and washing at a low temperature. What is certain is that the best way to reduce microfibre shedding is to wash our clothes less frequently. We can also rethink the fibres in our wardrobe and choose wisely when buying new clothes.

Finally, we can all use our voice and our power to demand that brands and legislators work to reduce the trillions of microfibres flooding into our waterways. That’s why Fashion Revolution has just launched a new hashtag #WhatsInMyClothes.

Fashion Revolution’s Manifesto states, “Fashion conserves and restores the environment. It does not deplete precious resources, degrade our soil, pollute our air and water, or harm our health. Fashion protects the welfare of all living things and safeguards our diverse ecosystems”. If we all work together, we can, and must, create a global fashion industry that conserves and restores the environment and values the wellbeing of everyone and everything living on this earth and in our oceans over growth and profit.

[1] Boucher and Friot, 2017

[2] Napper and Thompson, 2016

[3] Leonard, 2016

[4] Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017

[5] Olivetti et al., 2015

[6] Textile Exchange, 2017

Tomorrow I will be joining eXXpedition to sail some 2000 nautical miles from the Galapagos to Easter Island as part of an all-female Round the World voyage to gather the first global dataset of microplastic and microfibre pollution. From Ecuador to Chile passing by Peru and Bolivia, we are sailing past the cultures and communities I studied for my MA in Native American Studies, and subsequently worked with for over 20 years with my brand Pachacuti.

The Andes mountains run down the spine of the Pacific coast of South America. Andean philosophy sees all individuals as being part of a community, an ayllu. Humans are not separated from the natural world; they are two parts of a whole, each dependent on the other and giving to the other through a reciprocal relationship which sustains the community. The ayllu does not have fixed physical borders but is formed from the complex interlinking of relationships and an understanding of the fundamental interconnectedness of my interests, your interests and the interests of plants and animals. The ayllu is a place of nurture and regeneration and is seen as the basic cell of life. People, plants, animals and the earth itself nurture and are nurtured in a symbiotic relationship.

In indigenous cultures around the world, and particularly within indigenous cultures in the Americas, it is common that nature speaks. Ecuador has drawn from its indigenous past and became the first country in the world to legally recognise the rights of nature in 2008. It has given nature back its voice.

Last week I talked to Zapotec textile artist and weaver Porfirio Gutierrez from Teotitlán del Valle, Oaxaca, who explained that in his culture’s traditional philosophies, the plants are just like us. His parents would take him up into the mountains to collect plants for dyes and his father would talk to him about how they needed to have respect for the plants and trees because they are alive, just like us, and no life is more important than the other. “These days when everything is fast, everything is chemical, everything is plastic, we are forgetting the principles of being a human being, the slow way of living, the growing of food, making a textile. To me it is really important to create a conversation around that and educate people, and re-educate people”.

As I worked on the research for this year’s Fashion Transparency Index, I saw company report after report, referring to the preservation of natural resources, but even in attaching the word resources to nature we are effectively commodifying the planet, protecting it to support ever-increasing productivity. When studying Quechua, I learnt that there is no word for possession in the language. You cannot say ‘I have’. Everything you have or possess – not just goods and resources but also power and authority – are instead either with you, or not with you, meaning you are the steward, not the owner. This way of thinking changes everything.

Our challenge this decade is to move beyond our currently destructive Western worldview which is tipping us into a climate crisis and a plastic pollution catastrophe, towards a fashion industry which integrates nature in a truly sustainable way. We need our legislators to learn from the law passed in Ecuador and restore a voice to the oceans, earth and all that live in and on them. We need brands and retailers to move from competitiveness to collaboration and from the commodification of natural resources to working alongside nature in all her diversity in a way that is respectful, renewable and regenerative. We need them to look at longer lasting value systems than profit, prioritising instead the protection of our ecosystems and the wellbeing of our communities. And as citizens who have lost touch with the reality of living in mutual nurture and interdependence with the natural world, we need to rebuild our connections with how our textiles and clothes are made, the slow way, in balance with plants, animals, earth and water.

I believe that transhistorical community value systems can present a powerful counterpoint to the logic of generating profit now and help us to once again rediscover the spirit of the ayllu.

Colour is a catalyst for sales success within the fashion industry; it is the first thing consumers notice about a garment. Before feeling the fabric, trying on for size, or considering the manufacturing processes, colour preference impacts the eye. According to Michael Braungart and William McDonough, on average, only 5% of the raw materials involved in the production and delivery processes is contained within a garment. It is therefore important that we also pay attention to the 95% of the material process that we do not see; a vast component of which is hidden water.

Thick, ink-like water flows through rivers surrounding garment factories; a toxic soup of chemicals discarded from the fashion industry’s synthetic dye processes, filtering into the water systems of the planet. Why is colour – this fundamental component of fashion production – allowed to pollute water systems throughout the world? As much as 200 tonnes of water are used per tonne of fabric in the textile industry. The majority of this water is returned to nature as toxic waste, containing residual dyes and hazardous chemicals. Wastewater disposal is seldom regulated, adhered to or policed, meaning big brands, and the factory owners themselves are left unaccountable. Examples of synthetic dyes are disperse, reactive, acid and azo dyes. Natural dyes, meaning colour obtained from naturally occurring sources – are another source of colour for textiles, but these are rarely employed on industrial scales.

Azo dyes are a commercially popular colourant for textiles. They are popular because they can be used at lower temperatures than Azo-free alternatives, and achieve more vivid depths of colour. But some are listed as carcinogens, and under certain conditions, the particles of these dyes can cleave (producing potentially dangerous substances known as aromatic amines). Upon contact with the skin, these can be harmful to humans and pollute water systems. Legislation exists in certain countries, including EU member states and China, that prohibits the sale of products containing dyes that can degrade under specific test conditions to form carcinogenic amines, but low traces of these amines have still been found in garments.

Natural dyes are a frequently suggested alternative, but like many brands guilty of ‘Greenwashing’ their processes, natural dyes on an industrial level give the impression of good behaviour, whilst introducing pollution problems of their own…

With production levels continuing to rise, and consumer demand for colour failing to diminish, alternatives to the current dyeing methods and regulations for water processing must be imposed.

HOW DOES THIS POLLUTION HAPPEN?

Much of the water used within production is utilised during the dyeing phase. Post-production water containing residual dye, mordants, chemicals, and micro-fibres is expelled into water streams untreated. This is frequently through pipes untraceable back to source, meaning factories can commit this offence anonymously. These hazardous chemicals do not break down as they enter rivers then oceans, making their way around the world.

In China, over 70% of the rivers are polluted (River Blue Documentary), meaning many of their 1.4 billion population cannot access uncontaminated water Ground water is contaminated, rendering wells unsafe for collecting water for domestic consumption. Billions of tonnes of wastewater are expelled from factories untreated, lowering dissolved oxygen within waterways to levels unable to sustain life. For the communities surrounding China’s Li River, and the factory workers handling these chemicals, exposure to toxic, potent and potentially deadly chemicals occurs on a daily basis.

WHO IS TO BLAME?

Western brands outsourcing the majority of their manufacturing are the main culprits, yet the impact of this devastating pollution is not experienced by the brands who perpetrate it. The rivers of high garment export countries are becoming unable to sustain life of any kind. Toxic to drink, an irritant when in contact with skin, and deadly to aquatic life, many of the rivers upon which communities rely are causing decreased life expectancies and increased health problems.

Professor Arjen Y. Hoekstra, creator of the water footprint concept explains the reality of the outsourcing of garment manufacturing to countries such as China and Bangladesh- two of the biggest exporters in the apparel industry:

“Many countries have significantly externalised their water footprint, importing water-intensive goods from elsewhere. This puts pressure on the water resources in the exporting regions”. In this way, the offenders continue to live with safe water and ever-expanding wardrobes, ignoring their far away trail of water devastation.

COULD NATURAL DYES BE A SOLLUTION ON AN INDUSTRIAL SCALE?

This debate is not a simple one.

Natural dyes are derived mostly from plants, seeds, fruits, barks, lichens and in some cases, insects. Though natural dyes have connotations of wholesome, toxin free textiles, this is not necessarily the case. Like synthetic dyes, they require a lot of water during production.

Though the dye materials themselves are not pollutants to water, the chemicals employed to fix the colour to the fibres are. These fixative chemicals are called mordants. Ground water and river pollution would occur if metallic compounds were used as mordants and not disposed of responsibly; the same problem synthetic dyes create.

SIDE NOTE ON CHEMICAL MORDANTS…

The term ‘mordant’, from the Latin term ‘mordere’, translates as ‘to bite’. This is a fitting name, as the objective of a mordant is to bond the dye with the fabric. Shades achieved with natural dyes are rarely as vivid as synthetic alternatives, and fade quicker from sunlight and wash cycles. Perspiration and PH levels of the skin can effect the colours achieved by natural dyes. The obvious remedy to this is the application of chemicals as mordants to fix the dyes and improve their longevity, vibrancy and resilience. But isn’t this defeating the object?

Whilst relatively harmless compounds can be used as mordants on domestic levels, such as sodium chloride (table salt), and diluted acetic acid (vinegar), when metallic salts are used things become more complicated.

Harmful and potentially lethal compound substances such as Potassium Dichromate (chrome), Stannous Chloride (tin), Copper Sulphate and Iron Sulphate are regularly used to achieve vivid shades with natural dyes.

Though the brilliance of these mordanted shades may be more commercial, these metallic substances effectively render the pollution free intention of natural dyes futile. It is possible to dispose of the chemically contaminated waste water safely, but this would require the same factory processing infrastructure that is currently lacking with synthetic dyes.

Without mordants, the colours achieved are more vulnerable to fading, potentially leading to shorter garment life. Indeed, these nuances in shade and the ever changing hues are arguably part of their beauty. The reality however is that whilst this is marketable where narrative engagement between consumer and textile lifecycles occurs, the fast fashion industry would unlikely engage with this.

Some natural dyes, known as Substantive Dyes, are high in tannins, which can adhere to fibres without the use of mordants. This is an area where small brands and start ups can utilise natural dyes, toxin free and enrich their designs with the narrative of sustainably produced colour. The history contained within natural dyes is an engaging consumer tool.

Many natural dyes are harvested from fragile environments, whilst agricultural land would also be necessary for production of industrial quantities of dye materials. Natural dye pigments only bond with natural fibres, meaning industries relying on petrochemical or regenerated yarns would not be able to use them. Best colour results are achieved on untreated protein fibres, with softer tones on cellulosic. Silk achieves vivid, sumptuous shades, but the silk industry is a point of animal welfare contention in itself. Therefore natural dyes create higher demands for raw materials, not just for the harvesting of dye sources, but for the processing of natural fibres. Treatments and finishes applied to natural yarns to improves fibre performance and extend garment life would also impact colour uptake.

Traceability in the supply chain of growing; harvesting and processing the raw materials present further issues. Indigo has a 5000 year history, from its beginnings as a dye stuff. Exploitation of the Indigo (blue) and Logwood (purple) trades was endemic in earlier centuries. Should natural dyes be employed again on industrial scales, the welfare of workers throughout the supply chain would have to be regulated in order to avoid the repetition of history. Sourcing from accredited suppliers and implementing strict regulations would be essential. As illustrated however, regulations across the fashion industry are inadequate and insufficient.

Important to consider too is the vast amount of land that would be required to grow enough natural dye stuffs to cater for the entire textile industry.

Natural dyes are therefore not a simple solution to the water pollution crisis but they do represent an important step. Different but equally important and challenging problems arise from their use.

WHAT DOES ALL THIS MEAN FOR THE FUTURE OF COLOURFUL FASHION?

The current textile dyeing systems are guilty of water pollution on a global scale. The waterways of our planet are ceasing to host life and endangering communities.

Factories claim costs of new infrastructure to process their water waste are too high, and with the fashion industry paying so little for their production to increase profit margins on their fast fashion, the factories are often unable to invest. Combined with this, a lack of education on the importance of the issue, and fundamentally a lack of care or compassion from the biggest brands contribute further to the crisis.

Putting pressure on brands for transparency in supply chains, and adjusting our expectations as consumers to purchase less and reject endorsement of fast fashion are ways we can individually make an impact. Green Peace’s Detox campaign has gone a long way in pressuring brands to reduce and remove chemicals from their water processes, but Greenwashing is still prevalent amongst many retailers; more must be done. Looking past colourful aesthetics to the morality behind the creation of our clothes will facilitate positive change.

***

Beth Ranson is a practice-based knitted textile designer and researcher in biodegradable fibres. Motivated by problem solving in circular, sustainable design contexts, Beth occupies the space between design and sustainability theory: and it’s an interesting space to be. As a specialist in the use of natural dyes, Beth researches the beauty held in their narrative, as well as their potential negative impacts on the environment.