Photo: Shilpi Rani Das started working in a garment factory when she was 12 years old and moved to work at Rana Plaza at 13. She was working on the 8th floor at the time of the factory collapse. She lost an arm and spent the next 2 1/2 years in hospital. She is now at school, plays badminton and supports her family by sending money home. She is starting Open University.

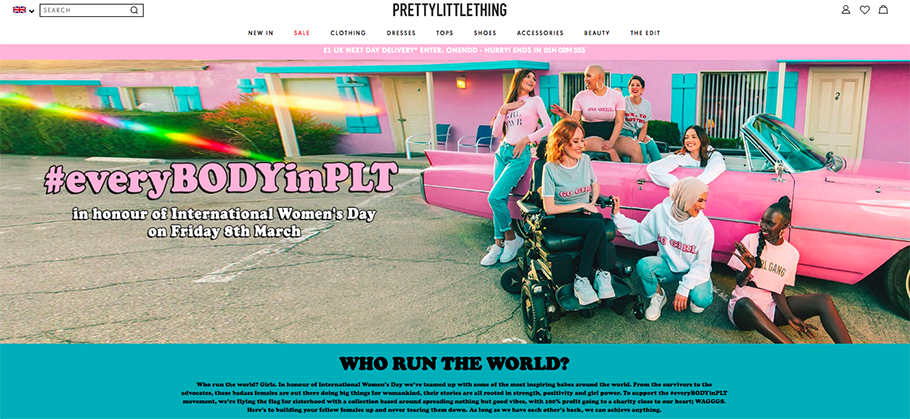

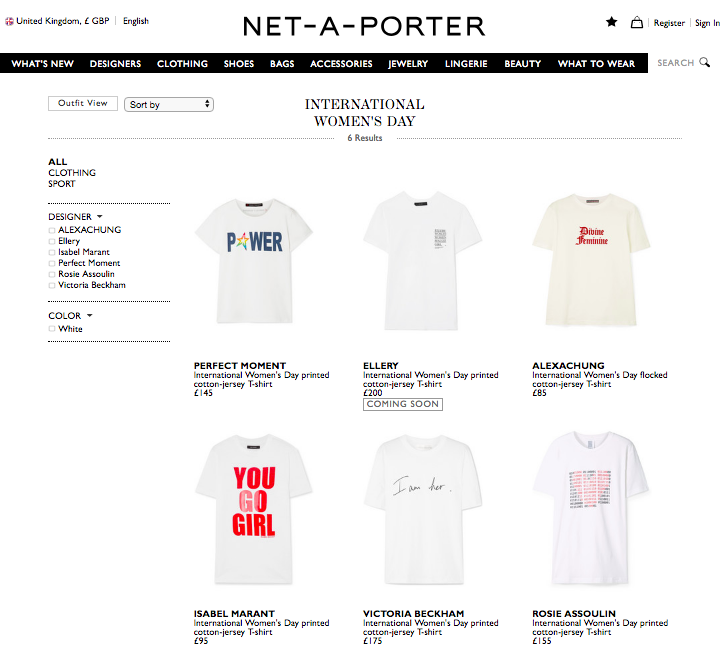

The theme of International Women’s Day 2019 is #BalanceforBetter and asks how we can help forge a more gender-balanced world. Brands and retailers are, predictably, all doing their bit to show support, from Pretty Little Thing’s promotion of their #EveryBodyInPLT movement with T-shirts from £10, with profits going to the charity WAGGGS to Net-a-Porter’s limited edition collection in collaboration with six female designers, with profits going to Women for Women International.

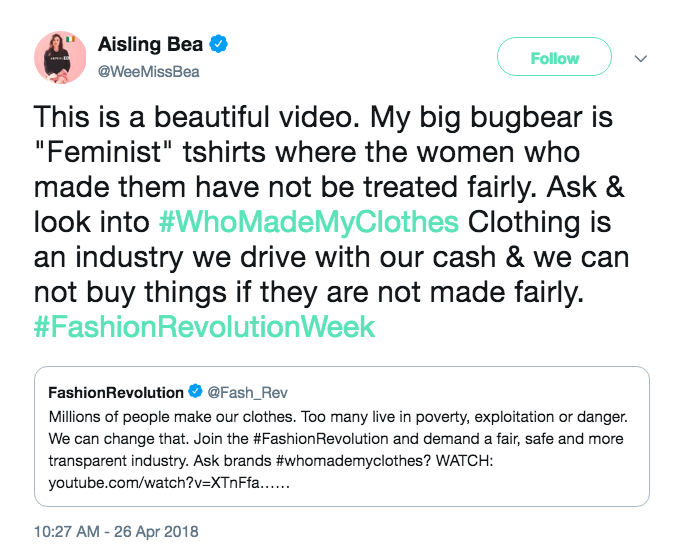

None of the webpages about the T-shirts feature any information about how or where they are made or who made them. About 75 million people work directly in the fashion and textiles industry and about 80% of them are women. Many are subject to exploitation and verbal and physical abuse. They are often working in unsafe conditions, with very little pay.

Actress Aisling Bea tweeted during Fashion Revolution Week last year: “My particular bugbear is feminist tees which were not made by women who were paid fairly for their labour. Check your tags and brands.”

Slogan T-shirts with female empowerment messages will be everywhere this week to coincide with International Women’s Day, but the reality is that the fashion industry doesn’t empower the majority of women who work in it. Gender-based inequality remains a problem throughout the industry, from the highest levels of management to the shop floor and the factory floor. We still have a very long way to go until everyone who makes our clothes can live and work with dignity, in healthy conditions and without fear of losing their life.

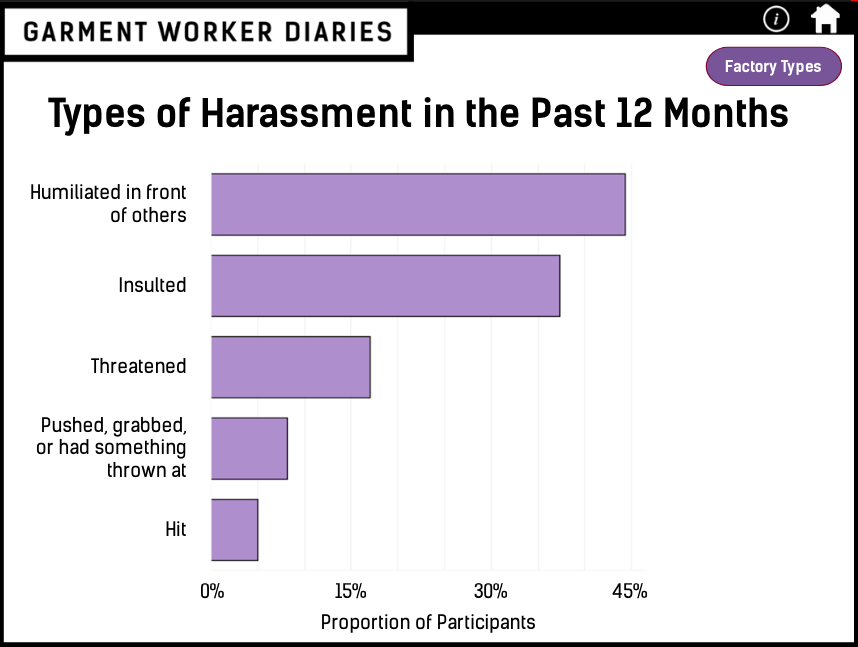

One of the main projects Fashion Revolution worked on in 2017/18 was the Garment Worker Diaries. On-the-ground research partners met with 540 garment workers in India, Cambodia and Bangladesh on a weekly basis for twelve months to learn the intimate details of their lives. 60% reported gender-based discrimination, over 15% reported being threatened and 5% had been hit. When I met with the President of the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association in November 2017, he told me categorically that sexual harassment doesn’t exist in garment factories in Bangladesh. One statistic I found particularly shocking was that 40% of the workers surveyed had seen a fire in their place of work. The women making our clothes are still risking their lives every day for our fashion fix.

In January, The Guardian revealed that Spice Girls T-shirts raising money for Comic Relief’s Gender Justice campaign were being made at a factory in Bangladesh where women earned 35p an hour and claimed to be verbally abused and harassed. Garment production in Bangladesh is still carried out in a very opaque manner and the lack of information about where our clothes and shoes are made and who made them is a huge barrier to changing the fashion industry. This means that gender inequality and human rights abuses and remain rife. If you can’t see it, you can’t fix it, which is why Fashion Revolution urges all brands and retailers to have full supply chain transparency, and we track this through our annual Fashion Transparency Index.

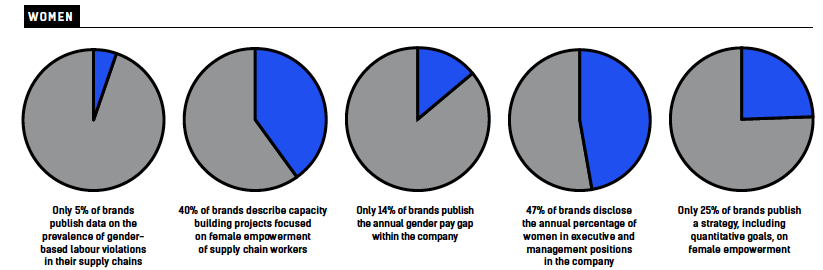

Fashion Revolution’s Fashion Transparency Index 2018 which reviews and ranks 150 major global brands and retailers according to their social and environmental policies, practices and impacts, throws a spotlight on how brands and retailers are tackling gender-based discrimination and violence in supply chains. The report specifically looks at how they are supporting gender equality and promoting female empowerment, both in their own company and in the supply chain.

Whilst, most brands publish policies on discrimination, harassment and abuse, the research show that only 37% of brands are publishing human rights goals. Without reporting on goals and, importantly, annual progress towards these goals, consumers have no way of knowing whether their clothing purchases are really helping to drive improvements for the women who are making their clothes.

Only 40% of brands and retailers reported on capacity building projects in the supply chain that are focused on gender equality or female empowerment, while just 13% publish detailed supplier guidance on issues facing female workers in their Supplier Codes of Conduct. Only 37 out of the 150 brands surveyed report signing up to the Women’s Empowerment Principles, an initiative by the United Nations Entity for Gender Equality, or publishing the company’s overall strategy and quantitative goals to advance women’s empowerment. Meanwhile, just 5% of brands are disclosing any data on the prevalence of gender-based labour violations in supplier facilities, such as sexual harassment and other forms of gender-based violence, or the treatment and firing of pregnant workers.

In the 2019 Fashion Transparency Index, to be published in April, we will be surveying 200 brands and asking the same questions around women’s empowerment. Women’s economic empowerment and closing gender gaps at work is key to realising women’s rights and central to achieving the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, in particular SDG 8 on promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all.

According to the BoF McKinsey & Company report The State of Fashion 2019 “Younger generations’ passion for social and environmental causes has reached critical mass, causing brands to become more fundamentally purpose driven to attract both consumers and talent”. As a result, the appearance of the word “feminist” on retailer homepages and newsletters is forecast to increase in frequency sixfold compared to two years ago. Brands are adopting feel-good feminist slogans, yet the rise of real feminism and female empowerment within the industry is a long way off for most women who work in it, from the highest levels of management to the shop floor and the factory floor.

If we really want to see a more gender balanced world, brands and retailers need to do more than sell empowering T-shirts; they need to make sure their policies are put into practice. And not just in the visible places, on fashion shoots or within their company, but at every level of their supply chains. The people making our clothes may not be visible, but every garment they make has a silent #MeToo woven into its seams. At Fashion Revolution, we believe positive change in the fashion industry is possible, and it starts with transparency.

Microfinance is based on the philosophy that even very small amounts of credit can help end the cycle of poverty. 70% of the world’s poor are women, and 80% of the world’s garment workers are women. Microfinance organisations typically lend to women, not only because they are considered a good investment as they are more likely to repay their loans, but also because lending to women brings with it a raft of social benefits for the women, their families and the wider community.

Microcredit has its advocates and its critics. Fashion Revolution will shortly be embarking on a year-long project in collaboration with MFO, Micro Finance Opportunities, and BRAC. In preparation for our work, I started to read more about microfinance and I also booked a tour with Envia in Oaxaca, Mexico so I could hear stories directly from the beneficiaries of microloans.

Advocates of microfinance include former Chief Economist at the World Bank, Joseph Stiglitz, author of Making Globalisation Work. Stiglitz sets out the importance of community involvement in development projects. He says that the microfinance model pioneered by Grameen in Bangladesh is successful because it addresses the needs of the communities which it serves. Their loan schemes work because groups of women take responsibility for each other and support one another in the loan repayment process.

But microfinance has its critics as well. Ha-Joon Chang, author of 23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism says ‘If effective entrepreneurship ever was a purely individual thing, it has stopped being so at least for the last century. The collective ability to build and manage effective organizations and institutions is now far more important than the drives or even the talents of a nation’s individual members in determining its prosperity. Unless we reject the myth of heroic individual entrepreneurs and help them build institutions and organizations of collective entrepreneurship, we will never see the poor counties grow out of poverty on a sustainable basis.’

Chang illustrates the problem with an example of a Croatian farmer who buys a cow on microcredit. This farmer has to sell the milk from the cow, even if the bottom is falling out of the local milk market and prices are plummeting because hundreds of other farmers have taken out loans and are selling more milk. It is impossible for the farmer to turn himself into an exporter of butter or cheese as they don’t have the technology, organisational skills or capital. ‘What makes rich countries rich is their ability to channel the individual entrepreneurial energy into collective entrepreneurship’ says Chang.

Looking specifically at the Mexican context, a study by Poverty Action Lab into the impact of microcredit for women in Mexico found that microcredit increased access to formal financial services which helped businesses to manage their cash flow and enabled some existing businesses to expand. However, it did not increase household income, business profitability or prompt new business creation. It was found that most of the loans made by microfinance organisations were used to make up for a shortfall in income due to unexpected circumstances such as weddings, or the need to buy medicine for a family member.

I realised quite early on in my research that not all microfinance organisations are set up as not-for-profits. Microfinance is big business in Mexico.

Institutions which started out providing affordable credit to the poor have burgeoned into large commercial institutions. The average interest rate for a microloan in Mexico is 74%, with many loans incurring 200% interest per annum. It’s no wonder that 28% of microfinance borrowers in Mexico hold over 4 loans, and 11% hold over 6 loans, often all with different microfinance institutions. Instead of helping to raise borrowers out of poverty, these loans plunge them into a spiral of debt, from which the only temporary relief is another loan to pay off the existing loans. These rates are partly the result of the decentralised nature of microcredit lending, but institutions also argue that it is because of the high risk of lending to people with no credit history.

But, are the rural poor such a high risk? Joseph Stiglitz says that Grameen Bank in Bangladesh who give small loans to rural women found they had a far higher repayment rate than rich urban borrowers.

Before visiting the Zapotec community of San Miguel del Valle to meet the recipients of microloans, I asked Envia more about how they operate and what interest rate they are charging to their borrowers.

Envia was founded in 2010 and is currently run by four staff and a team of volunteers. Envia’s model is to provide interest-free loans which are funded through responsible tourism, such as the tour I took to meet the loan recipients. Envia’s tours are, in fact, the no.1 excursion in Oaxaca on Tripadvisor and certainly provide an authentic experience, as well as a unique insight the life and work of rural Zapotec women.

100% of the money raised from tours is put towards loans. Once this is repaid, the money is used for a second round of loans, and finally a third round of loans, education programmes and salaries. So the income from the tours is effectively recycled through the beneficiary communities 2.5 times. 340 women are being supported in six communities, with 2000 microloans distributed to date.

Envia lends exclusively to women as they are far more likely to invest in ways which benefit the family and, by extension, the community. As with the model in Bangladesh, at Envia the women also take responsibility for each other and in order to participate they have to form a group of three.

Before receiving the loan, the group of women take an eight part training course over 3 or 4 weeks within their community. This covers issues such as financial literacy, how to separate business and personal money, and how to calculate profit. Each of the three women will receive their own loan of 1500 pesos and must pay it back at either 100 pesos over 15 weeks or 150 pesos over 10 weeks. They can only proceed to the next level of loans once everyone in the group has paid back their loan. The next loan levels are 2500, 3500 and 4500 pesos and the women can decide their own repayment rate.

Women must attend weekly meetings within their communities and pay the loan back on a weekly basis. If, for any reason, they find themselves in financial difficulaties and are unable to repay their loan on a particular week, they are asked to make a minimal 20 peso contribution to show their commitment. If a woman doesn’t attend the weekly meeting, and doesn’t send her money with another member of her group, all three members of the group receive a 20 peso ($1) fine. The carrot and stick approach combining the support of group members with financial penalties clearly works well for Envia as they have a 99% repayment rate.

Another difference between the commercial microloan lenders in Mexico and Envia are the free educational programmes to help the women to grow their businesses. The women must participate in monthly business workshops which teach them about profit, promotion, PR, goal setting, branding and design. Other free classes include health, English, composting, computer skills and menopause – all of which are open to all members of the community.

Epifania Hernandez makes aprons. She is in a group with two other women. The first runs a small restaurant in San Miguel del Valle, where I enjoyed a delicious lunch. She is using her loan to buy the ingredients she needs for the restaurant in bulk, thus reducing her costs. The second runs a bakery and is likewise using the loans to purchase ingredients in larger quantities and to visit neighbouring towns to sell her rolls and empanadas. Even though I had just finished lunch, the fresh-out-the-oven bread was impossible to resist and I bought more to take back to my apartment for breakfast the next day.

In the Zapotec communities around Oaxaca, aprons are worn every day and form an integral and practical part of traditional dress. Epifania explains that there are fashions in apron design (current hot motifs include peacocks and grapes) and there is a skill in combining apron and dress colours together.

Epifania has been making aprons for 14 years and started work at the age of 14. She wasn’t that interested in school; embroidery was much more enticing. It will take her two to three days to make and embroider each of her beautiful aprons.

Epifania has been with Envia for a year and is now on her third loan which is for 3500 pesos. She uses the money to buy stocks of fabric and embroidery threads. If she has a good stock, people can choose their colour scheme when they order aprons from her, and this is increasing her clientele.

For Epifania, and the other two women I met on the tour, microfinance was working. For all three of the women, it provided a way to expand their businesses whilst reducing their costs as the loans were used to buy raw materials in larger quantities than they would otherwise have been able to afford.

Of course, the zero interest repayment on the loans is not something which many lending institutions, even those with the most benevolent of aims, can replicate. But the high repayment rate through several loan cycles, show that these rural women can be a good credit risk and would probably continue to be a good credit risk with nominal interest rates. The coupling of microloans with business education is another important factor in Envia’s success in helping the women to build sustainable businesses for the long term.

Chang criticises micro finance as he says that, in order to grow sustainably, countries need to channel individual entrepreneurial energy into collective entrepreneurship. However, community-based model of Envia is an example of collective entrepreneurship. Although loans are given individually, the women collaborate with other members of their community and they work together, supported by the educational programme, to explore ways to expand their business and take it to the next level.

Envia was only established six years ago and the long term success of this tourism-financed business model is yet to be seen. However, from an outsider’s perspective it certainly seems to be working, both for the enthusiastic overseas visitors who have the opportunity to understand how rural women live in this region and purchase direct from the producers, and for the 340 women in the Oaxaca region who are beneficiaries of Envia loans.

Administered in a sustainable manner, microfinance can undoubtedly be a powerful instrument of social change and empowerment for women in rural communities around the world. Microfinance can help to increase women’s financial, social and emotional independence, as well as improving their status within both their families and their community.

Shubhangi Singh Rathore works as a Production Merchandiser at Sadhna Handicrafts in Udaipur, India.

As a Production Merchandiser at Sadhna, I follow up with suppliers and coordinate the organisation’s internal production related work. I love my work. I studied my masters in Fashion Management and took this particular work as a profession. I am now implementing and executing the theory and knowledge that I have gained from studying.

Before working at Sadhna, I was working in Delhi as a Buyer in the ladies ethnic department with Texas Pacific Group (TPG) Wholesale Pvt. ltd-Vishal Mega Mart. They’re the biggest private equity firm, owning Visual Mega Mart, one of the biggest retail chains in India. It’s huge. That was my first job.

When I was a child, I thought I would become a naval officer! I used to watch a television program that used to play on Doordarshan and the name was Abhiman, which was based on the navy. My career aspirations changed every now and then, but that was the very first initial idea in my mind.

Soon after my graduation I got more inclined towards brands. This is because my friends were very brand savvy. Until the time of graduation, I was not a very brand savvy person. After meeting my friends who were quirky, I started hearing words like Zara, H&M and Abercrombie and Fitch. It sounded to me like there was a big brand garment industry out there.

My mum always used to compliment my eye. She would say I have a great taste in colour combinations and styling. Even if not always in regards to my own styling! So I thought fashion industry was a good choice for me to pursue a career with.

When I started my career in fashion I worked as a Buyer, now I am on the flip side, I am a vendor. When I was a buyer I was dealing with the vendors and regularly facing some challenges, such as with vendor management, timely deliveries and sales at better mark ups. On the other side, I know what the challenges are. Now with the blend of both jobs, I am able to bridge that gap. It’s not ethnic, western, whole, woven or knits, it’s about the knowledge that you acquire and gain and using this to get better designs. I will stay in production and upgrade my skills.

I decided to come back to my home town as it had been quite a long time away with my studies, internships, working and everything. I found some work in my own home town within the fashion industry. I was so lucky to get associated with Sadhna.

Five years down the line I see myself as a Category Head. This could be either with Sadhna, if it grows and thinks of having Category Heads in the future, or maybe with another brand.

As a Buyer, I have been to places where there are women operators and male operators. In other factories and setups I have been to people are more confined. They enter work and go. At Sadhna it’s more of a family. I feel whatever thoughts you have in mind when walking into the factory you can share it easily with another person. Here through chatting people can shed off their office and home load and when they exit, they take happy memories. I always notice that with the tone when the pitch is high everything is normal. Sometimes I witness quarrels, but it’s when people speak in whispers, “I think something fishy is going on!” When the buyers visit they hear shrieks and are like “my god, what is all the noise?” and I say “chill, we are laughy, chatty and noisy like a family!” Still, people work very hard. Sadhna keeps the balance between the corporate and social sector. We completely do not want to operate a corporate factory with no emotions. In terms of output and systems we are trained and documents are recorded. All the teams have documents, instead of documentation being in a person’s mind. We give more and more training on this. Even the work that I do, the coordination and follow ups, I always tell people this file contains these items, if I am not here you know how to document it.”

My previous boss, Mr Bharat Bhatia, was my role model. He had 16 years’ experience with knits and was a person who used to see a garment from the distance and be able to tell the price of the garment. In Sadhna, I admire Swati for her overall production handling expertise and Manjula for skills in handwork. Every now and then I make somebody new my role model. In the movies, I like Ahmed Kahn. I really like Sushmita Sen who was an ex Miss Universe. She is beautiful and independent and she is a single mother, very known. She is doing very big things for society but not that many people know about it.

There are so many challenges for working women in India today. Firstly, the society is the biggest challenge, then the family is the second one and the inner consciousness, which has been made stubborn, is the third one.

In Indian culture everything is a blend with the society. Society pesters every now and comes up with thoughts and with facts, which pressurizes a woman to change her decisions. I will give you an example, suppose if girl is aged 22 or 23 and further wants to work, the society will keep pestering the parents saying “this is her marriageable age, you should marry her off, why aren’t you marrying her?” or they will say “that girl got married, this girl got married, why isn’t your daughter married?” The society is always pressurizing parents and then families are pressurizing girls and women.

Inner conscience is meant in the sense that some girls know what they really want to do. But they then limit themselves and they create boundaries, therefore they never do what they really want to. If women really want to travel they should! But women won’t do it because the inner consciousness keeps telling them “you are an Indian girl, you don’t have to travel, you just have to be at home and if you want to travel it should be just 20kms to-and-fro, not more than that”. Women who do travel on their own in India are great. But generally, they are at home but travelling to fetch the wood to cook at night, they get water from the pumps, which is actually more travelling than men. But not enough in the outside world and women really want to travel more.

Personally, I would love to travel more, I have been doing it quietly, and especially when I was away from home I would travel to find out more about different cultures, meet people, learn songs in local languages and take lots of pictures! Now I am home, again you see it’s the inner consciousness that tells me: “how do I tell my parents I want to go out? I have to come up with reasons that I have planned a party or I have planned a vacation”. When I was living outside of my hometown in hostel, I didn’t need to explain. When you are at home, you are in front of the eyes of your parents and they keep a note of everything.

The main challenges for women in India are to work as per their choice, to marry as per their choice, to decide whether to stay in a family or to stay all by themselves, and studies, choosing disciplines as per their choice. There are more women studying now in India but difficulties still remain.

For International Women’s Day, Sadhna is planning an event on 8th March. We will play some games, to make the women feel special. Before I started working with Sadhna, I was not familiar with the views of “for the women, of the women, by the women,” I’d heard them in a democratic sense. We need to expand these prepositions with women. I want everyone to feel proud to be a woman that would be my message for International Women’s Day.