art & eden childrenswear is made by Texport Industries who run a number of social initiatives, trying to improve the lives of their employees and the towns in which they work. Some of their programs include providing additional vocational training for their garment workers, hosting free medical camps every quarter, running a free hospital and employing and supporting differently abled persons.

K. Sreenivasan, Tailor (31 yrs old)

K. Sreenivasan has been working as a tailor at Texport Industries for over ten years. He lives with his wife, Vanitha Mani, and their two children.

Born in Sengottai, India, K. Sreenivasan grew up with his parents and went to a government run school in their town. He later moved to Tirupur to help his grandfather with agricultural work while attending the local government high school.

Similar to the disparity between public and private education in the United States, a large learning and resource gap exists between government run and private education in India. In most cases, if a family can afford to send their children to a private school, they do. As Vikas Bajaj and Jim Yardley reported in their New York Times article on Indian education:

In India, the choice to live outside the faltering grid of government services is usually reserved for the rich or middle class, who can afford private housing compounds, private hospitals and private schools. But as India’s economy has expanded during the past two decades, an increasing number of India’s poor parents are now scraping together money to send their children to low-cost private schools in hopes of helping them escape poverty.

Many government schools struggle to provide adequate electricity, functional resources and educational resources, let alone small class sizes and high quality teaching.

Thus, when K. Sreenivasan joined the workforce instead of going to college at the age of 20, it was a natural next step for him. His parents later joined him in Tirupur and helped him get a job as an office boy. Soon after, he was introduced to Texport Industries where he was hired as a tailor helper. He told us, “Gradually I learned the job of Tailor and gained a thorough knowledge of flatlock, overlock and singer work.”

He married his wife when he was 25 and they went on to have a son and daughter. Today, their son, Deebakkumaran, is eight years old and their daughter, Vidhya, is three.

Despite the lack of access to private education and opportunity, K. Sreenivasan keeps a positive attitude. He is optimistic about the future and finds joy in his daily life.

Every morning, K. Sreenivasan drops Deebakkumaran and Vidhya off at school before continuing on to work. He rides his two-wheeler scooter to the factory, a situation he calls “perfectly suitable because [his] residence is nearby, within 30 minutes!”

K. Sreenivasan takes pride in his work. He told us: “I am a very good tailor. I know flatlock, overlock and singer in all types of machines. [I also] support my team members to execute the buyer’s needs.”

For lunch, K. Sreenivasan rides his scooter home to “take full meals with pure vegetables with [his] family members.” After work, he returns home to help his wife with household duties. Then together they support their kids with homework and get them ready for school the next day. Some evenings, K. Sreenivasan takes his children to Karate and yoga classes, activities he tells us are very popular right now in his hometown.

For his own fun, K. Sreenivasan reads newspapers and watches T.V. “I am always memorizing the film songs and taking my family to the cinema for their entertainment!” he says.

When asked about his ambitions, he said, “My ambition is to make an orphanage home for at least 10 children.” He also added that he wants to make his family cheerful, always!

S. Malar, Checking Department (41 yrs old)

S. Malar has worked at Texport Industries for over six years. She likes the location of the factory because she lives close by, only twenty minutes away. She said the short distance lets her finish all of her housework in the morning and get to the factory in a peaceful manner.

S. Malar was born and raised in Thuraiyur, India where she attended the government girls school up through high school. Like K. Sreenivasan, she began working immediately afterward, doing household work and local jobs in town.

She married at 21, had her first son when she was 23 and had a daughter two years later, a relatively average timeline for many women in India, particularly in smaller, less metropolitan cities. In rural villages and areas where women do not have a chance to receive any education, marriage age can be significantly younger (many are married before 18, the legal marriage age).

Today, S. Malar lives with her husband, son and daughter. Her son, S. Dinesh Kumar, is twenty years old, currently getting his bachelors in mechanical engineering. Her daughter, S. Saranya, is seventeen years old and studying in a school close to their home. Ambitious and determined, S. Malar works hard to give her children the education and opportunities she wasn’t able to have herself. She tells us proudly: “They are the number 1 students in their classes because [in] my after duty hours, I fully engage with them for their studies.” When they aren’t all studying hard, S. Malar spends time with them “by watching T.V., [attending] other cultural programs and supporting them in their basic needs.”

S. Malar has a packed morning during the working week. She has a routine similar to many women responsible for working and running the household. This is what her daily morning schedule looks like:

- Wake up at 6:00 am

- Prepare the family’s morning tiffin (breakfast)

- Cook mid-day meals for the family

- Get the children ready for school and college

- Help husband get ready for work

- Leave for the factory

Even though she has long days and works hard, S. Malar knows she can rely on her and her husband’s combined income to keep them secure. She says: “Our earnings are sufficient for the family’s needs and our children’s education.”

When asked about her ambitions, she said, “My future dream is for our children to become an engineer and lawyer and to improve the status of our family to a better level.”

About art & eden

Susan Correa, founder and CEO of art & eden, has spent her entire career in the apparel industry. She knew first hand the result of low-price competitiveness and quick turn-around pressures in the fashion industry: it created an industry model of as cheap and as fast as possible, no matter the cost. What was that cost?

The environment. The rights and protection of factory workers. Fair wages. Quality materials. Caring for the earth and for the people on it.

When Susan founded art & eden, she was determined to pave a new path, one that was better for people and better for the planet. She refused to hire or collaborate with anyone who didn’t share the same vision, insisting that heart come first, that art & eden be mission-based, not profit-based.

She decided to produce art & eden’s children’s clothing line with Texport Industries after visiting their factories and seeing first-hand their safe, clean and healthy work environment. She was impressed with the positivity and the supportive energy she witnessed at the factory.

Note: The above interviews were conducted by Mr. Ramalingam, Administrative Manager of HR at Texport Industries, and written/transcribed by Nandita Batheja, writer and program facilitator at art & eden.

What the lives of garment workers can teach multi-national brands and their customers

Fatima, Sokhaeng, and Usha are all garment workers making clothes for multi-national brands in factories across South and Southeast Asia. Fatima lives and works in Dhaka, Sokhaeng in Phnom Penh, and Usha in Bangalore. Their work is similar—cutting and sewing garments for eight or more hours per day, but their lives and the lives of their compatriots also vary in important ways. What can the lives of these women teach multi-national brands and their customers about how to create and maintain sustainable supply-chains, where people who make the clothes that the world wears are treated with respect and do more than just survive? In other words, how can brands, with the support of consumers, win the “race to the top” where all do well, rather than the proverbial “race to the bottom” where brands compete by getting as much out of their workers for as little as possible?

Fatima, Sokhaeng, and Usha are three of 540 women that Microfinance Opportunities has been tracking for the last eight months or so. We have been asking them about how they earn and spend their money, their daily schedules, whether they are happy, in pain, or suffered an injury, the conditions in their workplace, and any special events that happened in their lives. From this information we have been able to weave together the individual stories of the workers, as well as generate an aggregate picture of the lives of the women who make our clothes. You can find accounts of these stories here for Bangladesh, Cambodia, and India.

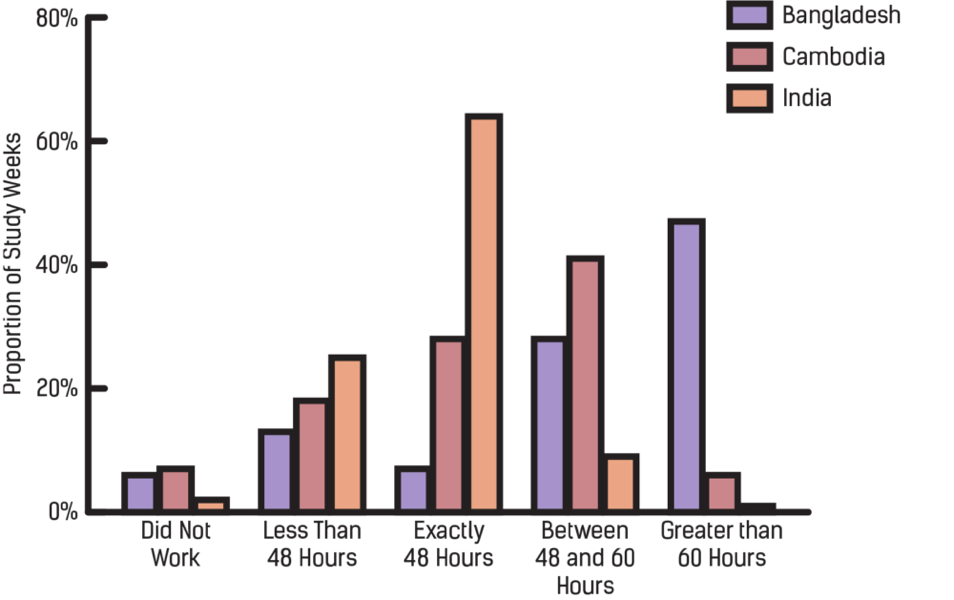

Fatima and others like her who are participating in the Garment Worker Diaries in Bangladesh often worked over 60 hours a week in the latter part of 2016 during the first few months of the study. In contrast, Usha and the other workers in Bangalore invariably worked 48 hours a week or less—still a lot but far less than the women in Bangladesh. The women in Cambodia fell somewhere in between—48- to 60-hour weeks were the most common in Cambodia. Furthermore, in both Bangladesh and Cambodia, the number of hours the women worked per week varied far more than they did in India, where the women consistently reported 48-hour weeks.

Figure 1: Hours Worked per Week

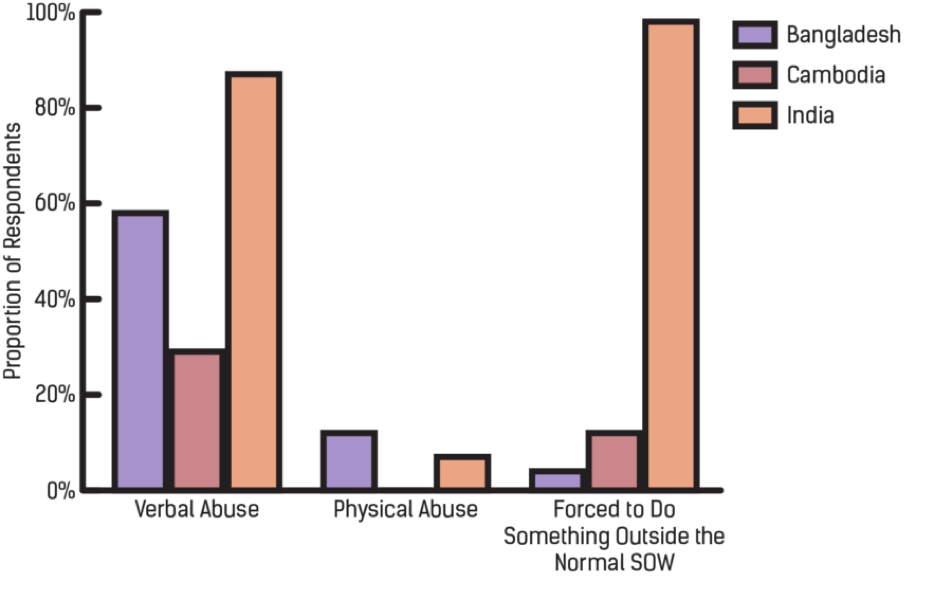

From the reports of how many hours they worked and how they varied from week to week, it looks like the women in India are the best off. But this is not altogether the case. Usha and her Indian counterparts reported far higher levels of verbal abuse in the workplace than did the women in Dhaka or Phnom Penh. And women in India consistently reported being forced to do more work than their allotted quota for the day. Meanwhile, women in Cambodia had the fewest reports of verbal abuse and no reports of physical abuse.

Figure 2: Reports of Abuse at Work

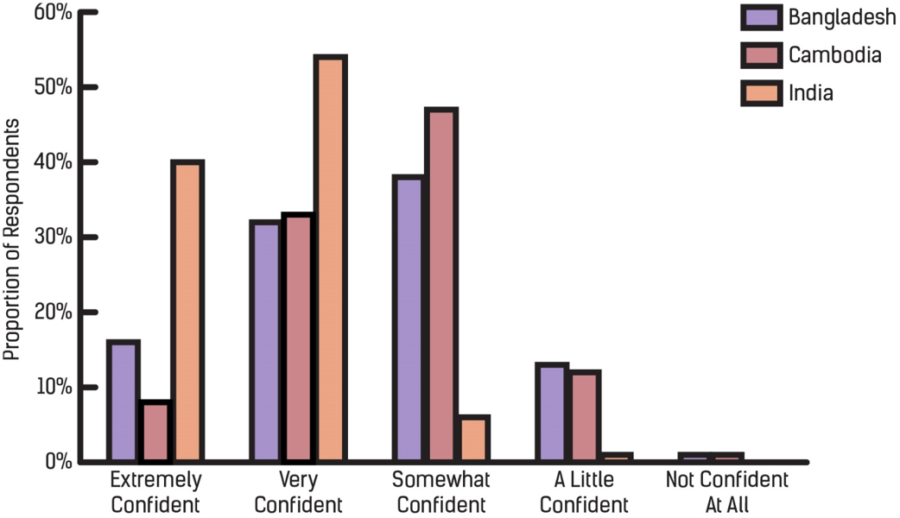

Further complicating the picture, women in Bangladesh and Cambodia participating in the Diaries study reported having mixed levels of confidence in whether they would be able to use the emergency exits in their workplaces in case of an emergency—almost 40 percent of Bangladeshi and 50 percent of Cambodian workers were only somewhat confident, while the Indian women reported the most confidence—over 90 percent reported they were extremely or very confident.

Figure 3: Confidence in Use of Emergency Exits

There may, of course, be differences across the countries in how the women perceive their situation, but even taking this possibility into account the differences across countries are so great that it is hard to fathom that they are simply due to differences in perception. What these findings suggest is that just because a set of factories in one country have worse conditions than factories in another country on one dimension does not mean that they have the worse conditions on all dimensions. So why can’t factories in Bangladesh and Cambodia and the brands that hire them have their workers work reasonable hours? Why can’t Indian factories stop the verbal abuse their workers suffer? Why can’t the Bangladeshi and Cambodian factories ensure that their workers can use designated exits in an emergency?

From a human rights perspective we can simply argue that the factories and the brands that hire them should stop treating their workers badly and adhere to some basic standards—higher than the best experiences of the women in our study. But these findings suggest that even by the lower standards of “business necessity” there is no justification for the behavior of the factory managers and the brands that hire them: other factories are able to treat their workers better in certain ways and stay in business, so why shouldn’t all factories be able to do so? In other words, there is no excuse for the treatment of the workers that the Diaries data are revealing, even by the lower standard of “we have to treat our workers this way just to stay in business.” It is time that the brands send this message loud and clear to factory managers, and that consumers ask the same of the brands. This way, maybe we can see the beginnings of a “race to the top.”

Authors: Conor Gallagher and Guy Stuart, Microfinance Opportunities

Four years ago today, a fire at the Tazreen Fashions factory outside Dhaka killed 112 garment workers and injured nearly twice as many. In its aftermath, there was an international outcry calling for greater regulation of health and safety conditions in garment factories across the country. Clothing brands and retailers came together and agreed to better monitor conditions inside the garment factories where their clothes are made; and then, after the Rana Plaza disaster, the Bangladeshi government adopted new legislation to strengthen its regulatory body in conducting safety inspections. As of March 2016, the Department of Inspection for Factories and Establishments had inspected 1,549 ready-made garment factories across the country.[1] Despite these steps, workers in garment factories continue to face poor health and safety conditions not only in Bangladesh but in other major garment exporting countries as well. These poor conditions do not necessarily result in major tragedies such as those at the Tazreen Fashions factory or Rana Plaza, but they nevertheless expose the workers in the factories to unsafe conditions and cause them undue pain and suffering.

Through the Garment Worker Diaries project, research teams in Bangladesh, Cambodia, and India have been collecting weekly data on what garment workers earn and buy each week, how they spend their time each day, and whether they experience any harassment, injuries, or other significant events while at the factories. Though we are still in the early stages of data collection, our project covers 540 workers from across these three countries, and we are hearing from them about the health and safety hazards they face.

Workers in our study have informed us about major events that have taken place in the factories. In Bangladesh, women from two different factories have reported fires. In the first case, a fire broke out during their lunch-break, and workers had to put it out themselves. In the second instance, a fire broke out during a midnight shift and took an hour to be extinguished. No casualties were reported in either case.

In Cambodia, one worker informed us that her factory’s owner had not paid their salary, so she ended up going to stand guard at the factory to try and force him to pay. She then filed a complaint in court against the owner in the following week, again asking him to pay. This was more than two months ago, and the situation has still not been resolved. We have seen similar incidents in Bangladesh. For example, six workers from a factory near Dhaka reported a factory-wide strike as the owner had not paid their salaries on time. This resulted in altercations with police officers, pressuring the owner to pay shortly after the fights broke out.

Not all issues that workers face are major events like fires or strikes; workers have been telling us about some more frequent and persistent challenges they deal with too. Workers in our study have reported on repeated harassment in the work place. These incidents range from being yelled at or insulted to sexual harassment. In Cambodia, workers have been willing to share with us the insults they receive. Some examples include women being called “idiots” or “crazy girls,” while one woman’s supervisor told her that she had “no bright future with [her] careless working style.”

Finally, the workers in our study tell us about the pain they endure because of their work. In India and Cambodia, for example, we have found that workers regularly report instances of chronic pain. Respondents in these countries have common ailments: for India, workers commonly experienced back pain. In Cambodia, workers most commonly have reported suffering from headaches. These types of pain are common among garment factory workers who face uncomfortable working conditions that require them to stand in hunched positions performing repetitive tasks for hours on end. Eventually, these conditions wreak havoc on the workers’ bodies, causing the types of chronic pain that our respondents regularly report. In three extreme cases, workers from India reported experiencing back pain every week, and they have reported that this pain can last anywhere from one hour to several days.

We are still in the early stages of collecting and analyzing the data from the 540 women participating in our study. As the Garment Worker Diaries progresses, we will continue to collect information on what is going on inside garment factories in Bangladesh, Cambodia, and India. We will use interviews and surveys to delve deeper into the specific working conditions that workers face.

We now ask you: what would you like to know about the women who make our clothes and the conditions they face at work?

Tell us by tagging us at @fash_rev #workerdiaries

The Garment Worker Diaries is a yearlong research project led by Microfinance Opportunities in collaboration with Fashion Revolution and with support from C&A Foundation. We are collecting data on the lives of garment workers in Bangladesh, Cambodia, and India. Fashion Revolution will use the findings from this project to advocate for changes in consumer and corporate behavior and for policy changes that improve the living and working conditions of garment workers everywhere.

[1] http://database.dife.gov.bd/

Header photo credit: IndustriALL Global Union

Fashion Revolution’s theme for 2017 is Money Fashion Power which will be exploring the flows of money and structures of power across the fashion supply chain.

“There is nothing more important than performance, and fashion brands have to perform because of this greed – not a percent or two per year, but at least 10 percent quarterly, even when we’re talking about billion-dollar businesses. There is no end to the greed, so the brands are spreading themselves thin”

said trend forecaster Li Edelkoort in an interview with Deutsche Welle published this week.

Tomorrow is the fourth anniversary of the Tazreen Fashions fire in Dhaka Bangladesh. All of the garment workers were on an overtime shift to complete an urgent order when the fire alarm sounded, but managers ordered them to carry on working. As the smoke and fire spread through the building and workers eventually tried to escape, they found that iron grilles barred the windows and the collapsible gate was locked. None of the fire extinguishers appeared to have been used which suggests workers had not received fire safety training. 112 workers died and more than 200 were injured. The official who led the inquiry into the fire said

“Unpardonable negligence of the owner is responsible for the death of workers.”

After the Tazreen fire, factories were told to replace collapsible gates and lockable doors with fire-proof doors so there was always a safe exit point in the event of a fire. In the Bangladesh Accord’s initial inspection of 1600 garment factories, it was found that over 90% had lockable, collapsible gates. According to industry insiders, around 40% of all operational garment factories still have these gates, four years later.

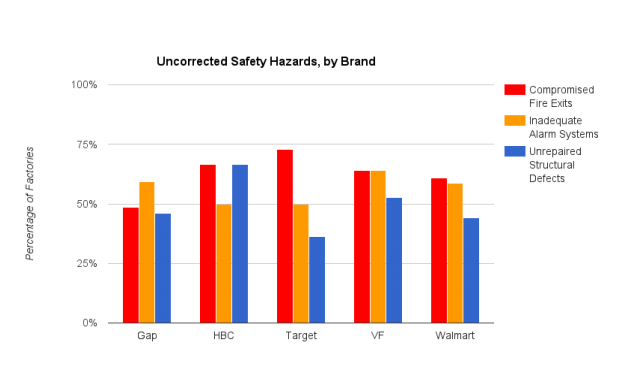

A new report published this week Dangerous Delays on Worker Safety found that of the 107 factories labelled “on track” by The Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety, 99 were still falling behind in one or more safety categories. In light of Li Edelkoort’s observation that brands are spreading themselves thin, it comes as little surprise to find that brands in the Alliance, which includes brands such as Walmart, Target, Gap inc, VF Corporation (which owns Lee, Wrangler, The North Face, Vans, Timberland and others and has just published its factory lists) have yet to put in place the life-saving safety changes they pledged following the Rana Plaza disaster, which occurred five months after the Tazreen fire. 62% of factories still lack viable fire exits, 62% do not have a properly functioning fire alarm system and 47% have major, uncorrected structural problems. Deadlines for these safety measures to be implemented were supposed to be 2014/15 but have now been moved to 2018, the end of the 5 year period over which the Alliance extends.

Are brands and factory owners really so concerned with the bottom line that they cannot afford to prioritise the installation of something so basic to worker safety as a fire-proof door and the removal of locks from existing doors?

Since the Tazreen fire and Rana Plaza disaster, human rights issues are certainly more visible than ever before and there is ongoing pressure on global fashion brands to become more transparent. Companies are now being held to a higher standard and they are cognisant of this change. During Fashion Revolution Week in April, over 70,000 fashion lovers around the world asked brands #whomademyclothes on social media, with 156 million impressions of the hashtag. G Star Raw, American Apparel, Fat Face, Boden, Massimo Dutti, Zara, Jeanswest and Warehouse were among more than 1250 fashion brands and retailers that responded with photographs of their workers saying #Imadeyourclothes. Read more about our impact here.

However, the harsh reality is that basic healthy and safety measures still do not exist for millions of people who make our clothes and accessories. On 11 November 2016, 13 people died in a factory making leather jackets on the outskirts of Delhi. The front of the building had been shuttered with a metal grill which prevented the workers escaping the blaze. Deadly accidents are still commonplace in fashion supply chains and not enough has been done by brands and retailers to prevent more fashion victims; victims of neglect, oversight and the pursuit of profit.

Scott Nova, executive director of the Worker Rights Consortium says:

“What motivated Walmart and Target to do the right thing is public embarrassment. We are three and a half years on [from Rana Plaza] and they assume memories are fading.”

We have the power and, I believe a duty, to let these brands know that our memories of the Rana Plaza disaster, the Tazreen Fashions fire, and the many other tragedies which have ocurred in the name of fashion, are not fading. By asking the question #whomademyclothes we are applying pressure in the form of a perfectly reasonable question that fashion brands should be able to answer. We are asking them to publicly acknowledge the people who make our clothes; millions of people working in factories, fields, homes and other hidden places around the world. Tragedies like the Tazreen Fashions fire are preventable, but they will continue to happen until every stakeholder in the fashion supply chain is responsible and accountable for their actions and impacts.

As Li Edelkoort said, fashion brands are spreading themselves thin. As their customers, we can help make sure they start to get their priorities right and redress the imbalances of power in the fashion supply chain.

Header photo credit: A young garment worker by Claudio Montesano Casillas

80% of our fashion is made by women (mostly 18-24 years old) but we only hear about these millennial makers when they’re associated with a tragedy like Rana Plaza in Bangladesh in 2013 or the infamous Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in New York in 1913. Their stories are eclipsed by heartbreaking headlines that hound the fashion industry.

But there is another part of this story. It’s a story of hope. Remake has traveled to factories and dormitories throughout the world in search of the women who never make the headlines. Kashmiri who opens the yarn to make it into fabric. Maud and Rubina who stitch our blouses and jeans together. Anju who pulls out loose threads and inspects everything to ensure perfection. Each has a story and a hope for a very different future.

Meet the women behind fashion’s supply chain — we followed them from Haiti to Pakistan to China — and asked each of them to share a message to you, the end shopper. These are their stories:

Kashimiri, Yarn opener, Panipat, India

I am 25 years old and already have 4 children. I sit crouched on the floor all day, opening spindles of yarn which go on to become fabric. Panipat has a lot of needs. Open sewers, flies and trash everywhere. Only recently my children starting going to school. I now hope that they will have a better future. Go on to be somebody. I hope you can see their faces in the threads of your fabric.”

Rubina, Hoodie Sewer, Karachi, Pakistan

I am 22 years old and wanted to be a doctor. Then my father got sick, so here I am, many years later, still at a factory stitching college sweatpants and hoodies that go to America. I don’t want you to feel sorry for me. I used to be shy and scared in the factory environment. But after all the injustices I’ve seen happen here, I’ve become a labor organizer. I go to management to demand that we are not harassed, paid on time, given proper food to eat. You would not believe the things I have seen. Stitching all day long my mind wanders and I think about you often. You having fun, wearing these hoodie on campus. I wonder if you think about me ever? The woman who made that for you. I am taking English classes at night. So that one day I can at least get an office job.

Maud, Jeans Sewer, Ouanaminthe, Haiti

The factory across from the Massacre river is like paradise, with its lush green trees and paved roads. I’ve been sitting down sewing your jeans here for five years. Recently my back and neck has been hurting a lot more. But without this job, I have no way to support myself or my six siblings. After a long day, I walked across the river into my community which is pitch dark at night. There is no electricity or running water, just human need everywhere. I want to save enough to go back to university and study computer science. I want you to think about your sister Maud in Haiti, when you put on your jeans. On dark sad nights I play on Facebook with my phone and dream of the day I can be just like you.

Zheng Ming Hui, Quality Assurance, Guangzhou, China

At 19 I left my village to experience the excitement of city life. Here I am three years later, still at the same factory. I work 12 hours a day, looking at beautiful, bright patterns to make sure that there are no defects. My mother wishes I would call her more. But mostly I miss my grandmother. I only get to see my family once a year for Chinese New Year and mom makes the biggest feast. My entire life is the factory. I live in the dorms with three roommates, work all day only stopping to eat at the cafeteria. On my one day off, I am too tired to do much so I play with my phone. At night I dream of bungee jumping. I want to find someone to fall in love with and travel the world for work, taking pictures and telling stories. But for now, I am here, making sure your clothes look nice. I picture you and I am sure you look BEAUTIFUL!

Anju, Fabric Inspection, Delhi, India

I once dreamed of a life that was very different. Where I could finish my education and become a teacher. Everything changed when I was 15 and married to a man with few means. For the last 10 years, I’ve been working in a factory instead. I am proud to be an equal bread winning partner with my husband and to know that my hard work allows my children to go to school. I stand on my feet all day, pulling loose threads out of finished blouses and tops. Making sure they are perfect for you. I want you to know that I recently took a health education course on making nutritious meals with little money. I now teach what I’ve learned at my children’s school on my day off. I guess my dream of becoming a teacher has come true after all.

A 100 pair of human hands touch our clothes before they get to us. Each one of these mothers, sisters, wives and daughters are fierce and hard-working. Dreaming like us to be healthy, happy and financially secure.

Share these stories on Twitter and Facebook with your favorite brands and say: I want to know the invisible people #whomademyclothes.

Together we can #remakeourworld

So what does community based political organisation (i.e. the kind that got Obama elected) and The Fashion Revolution have in common? Actually much more than you’d think.

The strength of Fashion Revolution Day is that it is a movement made up of hundreds and thousands of people each telling a story — of how garment workers and farmers made our clothes, of our deliberate decision to support conscious fashion and our collective efforts to spread more ethical practices.

Most often we are talking to each other — which is a good thing — but a key outcome of Fashion Revolution is, and should continue to be, getting other people to join us (a.k.a ‘growing the movement”) in transforming the fashion industry. But what is the most effective way of doing that?

I don’t come from a fashion background and so my entry into the eco-fashion world is rooted firmly in my training as an academic and as an activist. And as an activist, I bristle, alongside everyone else reading this blog, at the continued love affair our society has with cheap fast fashion. We all know the story. And the excuses.

So when we come across these pro- ‘Fast Fashion’ arguments from our friends and family and co-workers, what do we do? Turns out, the big “P” political movement (i.e. the ones that get people elected to parliaments) have a wealth of tools that can help us, as Fashion Revolutionaries, to start to break down these ‘Fast Fashion’ arguments. Chief among them is something called “the story of self”.

Let me explain.

Progressive political campaigners in their work argue that you can no longer win people over by presenting them with facts and figures. Facts and figures are still important, but they are not enough. Rather, we win people over by tapping into their core values and showing how these values can be expressed by joining in our Movement. And the most effective way of doing that, is by expressing our core values and engaging people on the story of why we are involved.

Ever been motivated into action by thinking “What if that was my child working in the factory?” or “how would I feel if my workplace was unsafe” or “what if that river was the source of my drinking water?” Then you already know what I am talking about.

Usefully, campaign theory (yes, there is such a thing!) gives us a neat little template, which we can use to tell a story about our ‘conversion’ to eco-fashion and, through this, engage people in a story that links the Fashion Revolution with the values important to them. It is about telling your story of why you are involved and it goes something like this.

- First, describe a challenge that you came across in the fashion industry that really motivated you to act. Did you look at the huge amount of waste in the fashion industry and think there has to be a better way? Or did you read the child labor statistics and think “what if that was my child”? Did you look at the water pollution from garment factories and thing I wouldn’t want to drink that?

- Second, describe your response to the challenge you saw. What choice did you make once your knew about the challenge? What different path did you see? Did you decide to cut back on your clothing purchases? Did you switch to upcycled/recycled/second hand or ethically made clothes? DId you learn how to repair your old clothes? Did you join Fashion Revolution (answer: yes!)

- Finally, provide the person you are talking with an opportunity to act — ask people to do something. Something small, this is not the time to overwhelm them with the challenge we face, but just something to get them started on making better clothing choices. For example, you could ask them to read the stories on the Fashion Revolution website.

See what you’ve done? You’ve described a situation that challenges an important universal and relatable value (desires to minimise environmental stress, prevent child welfare, or ensure clean drinking water), described how you changed (the person everyone can relate to because they are your friend, family or co-worker) and provided a template for your audience to follow suit.

You’ve provided motivation for change and a path forward to do so. And it shouldn’t take long – the whole story from start to finish should be about 2-3 minutes max.

If you want to explore more about this tool, and many others, Wellstone is a goodplace to start.

So, that’s the theory.

What does it look like in practice? Check out my story.

The story of my eco-fashion underwear brand Mighty Good Undies, started with my visit to India. I knew the facts and figures of the cotton industry and the potential benefits of certified organic and Fairtrade cotton, but at that stage it was all rather cerebral.

But it was only when I was sitting in the fields with the farmers from a Chetna Organics cooperative did I really get it: these people wanted to grow and sell organic cotton because organic farming meant they didn’t get sick all the time. And I realised ‘what if it was me getting sick at work?” Wouldn’t I want to change that?

And then the farmers added the kicker: many farmers wanted to join Chetna Organics but their ability to convert to organic cotton was limited by the demand for their product.

Well, I was hooked.

At that moment, I made a choice that I need to find ways to grow markets for organic and Fairtrade cotton so that more farmers, and more workers in Chetna’s production partner Rajlakshmi Cotton Mills, can get the benefits of this alternative form of trade and production*.

As the song says “From little things, big things grow…”

Happy Fashion Revolutionising

Hannah, Co-founder, Mighty Good Undies

* Okay, so starting a new ecofashion brand is probably not an option for most people, so you may want to start off with some of the brilliant suggestions in the book “How to be a Fashion Revolutionary” from the Fashion Revolution Website.

Shubhangi Singh Rathore works as a Production Merchandiser at Sadhna Handicrafts in Udaipur, India.

As a Production Merchandiser at Sadhna, I follow up with suppliers and coordinate the organisation’s internal production related work. I love my work. I studied my masters in Fashion Management and took this particular work as a profession. I am now implementing and executing the theory and knowledge that I have gained from studying.

Before working at Sadhna, I was working in Delhi as a Buyer in the ladies ethnic department with Texas Pacific Group (TPG) Wholesale Pvt. ltd-Vishal Mega Mart. They’re the biggest private equity firm, owning Visual Mega Mart, one of the biggest retail chains in India. It’s huge. That was my first job.

When I was a child, I thought I would become a naval officer! I used to watch a television program that used to play on Doordarshan and the name was Abhiman, which was based on the navy. My career aspirations changed every now and then, but that was the very first initial idea in my mind.

Soon after my graduation I got more inclined towards brands. This is because my friends were very brand savvy. Until the time of graduation, I was not a very brand savvy person. After meeting my friends who were quirky, I started hearing words like Zara, H&M and Abercrombie and Fitch. It sounded to me like there was a big brand garment industry out there.

My mum always used to compliment my eye. She would say I have a great taste in colour combinations and styling. Even if not always in regards to my own styling! So I thought fashion industry was a good choice for me to pursue a career with.

When I started my career in fashion I worked as a Buyer, now I am on the flip side, I am a vendor. When I was a buyer I was dealing with the vendors and regularly facing some challenges, such as with vendor management, timely deliveries and sales at better mark ups. On the other side, I know what the challenges are. Now with the blend of both jobs, I am able to bridge that gap. It’s not ethnic, western, whole, woven or knits, it’s about the knowledge that you acquire and gain and using this to get better designs. I will stay in production and upgrade my skills.

I decided to come back to my home town as it had been quite a long time away with my studies, internships, working and everything. I found some work in my own home town within the fashion industry. I was so lucky to get associated with Sadhna.

Five years down the line I see myself as a Category Head. This could be either with Sadhna, if it grows and thinks of having Category Heads in the future, or maybe with another brand.

As a Buyer, I have been to places where there are women operators and male operators. In other factories and setups I have been to people are more confined. They enter work and go. At Sadhna it’s more of a family. I feel whatever thoughts you have in mind when walking into the factory you can share it easily with another person. Here through chatting people can shed off their office and home load and when they exit, they take happy memories. I always notice that with the tone when the pitch is high everything is normal. Sometimes I witness quarrels, but it’s when people speak in whispers, “I think something fishy is going on!” When the buyers visit they hear shrieks and are like “my god, what is all the noise?” and I say “chill, we are laughy, chatty and noisy like a family!” Still, people work very hard. Sadhna keeps the balance between the corporate and social sector. We completely do not want to operate a corporate factory with no emotions. In terms of output and systems we are trained and documents are recorded. All the teams have documents, instead of documentation being in a person’s mind. We give more and more training on this. Even the work that I do, the coordination and follow ups, I always tell people this file contains these items, if I am not here you know how to document it.”

My previous boss, Mr Bharat Bhatia, was my role model. He had 16 years’ experience with knits and was a person who used to see a garment from the distance and be able to tell the price of the garment. In Sadhna, I admire Swati for her overall production handling expertise and Manjula for skills in handwork. Every now and then I make somebody new my role model. In the movies, I like Ahmed Kahn. I really like Sushmita Sen who was an ex Miss Universe. She is beautiful and independent and she is a single mother, very known. She is doing very big things for society but not that many people know about it.

There are so many challenges for working women in India today. Firstly, the society is the biggest challenge, then the family is the second one and the inner consciousness, which has been made stubborn, is the third one.

In Indian culture everything is a blend with the society. Society pesters every now and comes up with thoughts and with facts, which pressurizes a woman to change her decisions. I will give you an example, suppose if girl is aged 22 or 23 and further wants to work, the society will keep pestering the parents saying “this is her marriageable age, you should marry her off, why aren’t you marrying her?” or they will say “that girl got married, this girl got married, why isn’t your daughter married?” The society is always pressurizing parents and then families are pressurizing girls and women.

Inner conscience is meant in the sense that some girls know what they really want to do. But they then limit themselves and they create boundaries, therefore they never do what they really want to. If women really want to travel they should! But women won’t do it because the inner consciousness keeps telling them “you are an Indian girl, you don’t have to travel, you just have to be at home and if you want to travel it should be just 20kms to-and-fro, not more than that”. Women who do travel on their own in India are great. But generally, they are at home but travelling to fetch the wood to cook at night, they get water from the pumps, which is actually more travelling than men. But not enough in the outside world and women really want to travel more.

Personally, I would love to travel more, I have been doing it quietly, and especially when I was away from home I would travel to find out more about different cultures, meet people, learn songs in local languages and take lots of pictures! Now I am home, again you see it’s the inner consciousness that tells me: “how do I tell my parents I want to go out? I have to come up with reasons that I have planned a party or I have planned a vacation”. When I was living outside of my hometown in hostel, I didn’t need to explain. When you are at home, you are in front of the eyes of your parents and they keep a note of everything.

The main challenges for women in India are to work as per their choice, to marry as per their choice, to decide whether to stay in a family or to stay all by themselves, and studies, choosing disciplines as per their choice. There are more women studying now in India but difficulties still remain.

For International Women’s Day, Sadhna is planning an event on 8th March. We will play some games, to make the women feel special. Before I started working with Sadhna, I was not familiar with the views of “for the women, of the women, by the women,” I’d heard them in a democratic sense. We need to expand these prepositions with women. I want everyone to feel proud to be a woman that would be my message for International Women’s Day.

‘Black Friday’ 2015 is just around the corner. Traditionally it is the day after Thanksgiving in the US when shops do an all-out sale giving the customers a chance to stock up for Christmas. Well that’s what it used to be about. Be it the US or UK, in recent years, ‘Black Friday’ has come to symbolise something more interesting, our insatiable appetite to consume. We all remember seeing the images on TV, hearing the news update on radio and saw the news headlines of the incidences which marred this day. So much so that this year leading UK superstore have announced that they will not be participating in this year’s event even though all other major super stores are[i].

One may well ask, what Black Friday has to do with ‘sustainable development’? One word………..everything! Research after research has found that our demand for goods will soon out strips the natural resources available to make them. We know that in the UK garment workers are earning as little as £3 per hour for their work (University of Leicester Feb 2015[ii]). And those in faraway lands like Bangladesh, Vietnam, Myanmar and even Ethiopia are getting paid approximately £25-30 per month[iii]. But as consumers, we close off part of our thinking mind and all queue up, physically and on-line, waiting for that deal on Black Friday.

Sustainability in the fashion industry has been addressed right through its value and supply chain. In the manufacturing sector of garments, there are all kinds of machinery that optimises water usage for washing and drying of textile and therefore has a knock on effect on the level and amount of electricity and gas used. Buildings are more ‘green’ by using solar power or alternative sources of energy and reuse and recycle rain water amongst other things. More and more manufacturers are also looking more intently on how they engage with their labour force and the provisions that are available for them. Manufacturing factories in Bangladesh are actively pursuing ‘green manufacturing’ starting with the factory space and also the environment and support for their workers[iv].

Worn Again is working with H&M and Kerring[v] to not just recycle or upcycle but create new textile based on a ‘circular resource model’ from old or ‘end of use’ clothes. New materials are also being produced from natural fibers like pineapples or banana and from seed to harvesting all aspects of the plant/ fruit is reused. M&S’s ‘SHWOP’[vi] or Patagonia’s ‘Worn Wear’[vii] are two high profile schemes which promotes and advocates ‘longer-life’ for our clothes. There are workshops on knitting in groups bit like ‘Book Clubs’. Critiques of the schemes say that these schemes are destined for the wardrobes of the rich and middle-classes. Not for the mass public. Also that dropping of our ‘worn’ clothes to the ‘poor’ of the developing nations can actually cause problems for local brands, retailers and manufacturers[viii].

In a recent BBC documentary programme, ‘Hugh’s War on Waste’, the host looks to engage with individuals who do not believe that waste is truly recycled. They are taken to a local recycling processing plant and the sceptic recyclers are still not convinced by the argument for recycling waste. It is only when they are shown actual everyday products made from recycled material that we see the recycling sceptics change their outlook.

But if it is facts we are looking for there is plenty out there in the form of research, films, images, case studies and much more. For instance the recent film ‘The True Cost’[ix] has given a very detailed breakdown of how the fashion supply chain is set up and is costing. It has been distributed in cinemas, is available online and through social media platforms. So very easily available and accessible and we still have the situation of people not following through and buying less or not queuing for ‘Black Friday’.

So far I have concentrated only on the consumption habits of developed countries. However it is the with consumers of China, India and elsewhere that brands and retailers are trying to establish a relationship with. And that is because in emerging countries material consumption lead the way as more people have disposable income and also want to have the opportunity consume or at least aspire to consume as their counter parts in developed countries[x].

So what we see now is brands, luxury brands and every day retailers positioning themselves in these new markets. It is quite normal to see nappies for babies being sold in main cities and towns of these new territories. Long gone are the days when people would use ‘terry cloth’ nappies for their babies not only because they are time consuming to maintain but also they are seen as being ‘traditional’ and not representative of the ‘modern life’ that they now live.

So attitudes are changing everywhere. It’s cyclic. In that the developed world have started thinking about ‘sustainable development’ in all walks of life. They are exploring how corporations, supply chains and individuals can make a difference. The emerging and developing countries with a growing number of people with spending power and disposable income now aspire to consume and become active participants in this global consumer market. Internet has increasingly made everything accessible within a click of a button. Social media shows you trends on a daily, hourly, minute by minute basis to satisfy ones desire.

So the notion of ‘sustainable development’ is admirable but seemingly unachievable. Unless of course as in the case of fashion you have groups like Fashion Revolution Day and their mission to connect consumer to their clothes through the ‘#who made my clothes?’ FRD asks the consumer to do the following:

- Be curious – Look at your clothes with different eyes. Ask more than “does this look great on me?”. Ask “#who made my clothes?”.

- Find out – Get to know your clothes even better.

- Do something – tweaking the way your shop, use and dispose of your clothing

Be curious is the start point of looking at our personal shopping habits. Before we go get the latest design at a cut price from the shop, the question we must ask is ‘do I really need to buy this?’, ‘Will I wear it more than once?’, ‘do I know how to take care of it?’ and what will I do when I have had enough of it?’. These questions are alongside asking the brand ‘#who made my clothes?’ Fashion Revolution has run a very successful global campaign in 2014 and 2015 with consumers, celebrities turning their clothes ‘insideout’ taking a selfie of it and asking the brand ‘#who made my clothes?’

This new curiosity will lead us to the next step ‘Find Out’. If we do not know exactly what is happening then it is difficult to change our behaviours and attitudes. There are various organisations who work on specific issues like living wage, organic cotton or on themes ‘Fair Trade’. They are a good start point for any search[xi]. There are also apps available which will assist you whilst you are shopping to find out more about the social and environmental impact of the item[xii]. New apps are coming are being developed and trialled and aims to provide more detailed information on the item of clothing origin.

‘Do something’ is personally my favourite. It can be you ask the brand, #who made my clothes? Or look at projects like http://loveyourclothes.org.uk/ set up by WRAP which gives you tips on how to manage your clothes, revamp it and much more. As mentioned earlier, high street stores like M&S or brands like Kerring have also tried to inspire their customers with alternatives to just throwing our clothes away. What is possible is sometimes difficult to choose, so a helpful list is available from Fashion Revolution’s booklet, ‘How to be a Fashion Revolutionary’[xiii]

As discussed earlier, the consumer at present is detached from what they consume be it the clothes we wear or other products. We have seen that it is only when they come face to face with evidence, is it that they start to explore further the issues on hand. So that we can move away from the future of diminishing natural resources and an un-sustainable environment we need to change attitudes through curiosity, finding out and doing something.

Author – Maher Anjum – Sustainable Sourcing and Supply Chain (Garments, Textiles and Fashion) Consultant, Operational Director Oitji-jo Collective (Part-Time), Associate Lecturer, London College of Fashion and Member, Global Advisory Committee, Fashion Revolution.

References

[i] http://www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk/news/northern-ireland/asda-axes-black-friday-but-rivals-tesco-sainsburys-amazon-argos-currys-pc-world-halfords-and-john-lewis-banking-on-bonanza-34188894.html

[ii] http://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/sustainable-fashion-blog/2015/feb/27/made-in-britain-uk-textile-workers-earning-3-per-hour

[iii] http://www.waronwant.org/sweatshops-bangladesh

[iv] http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/22/business/energy-environment/conservation-pays-off-for-bangladeshi-factories.html

[v] http://www.kering.com/en/press-releases/hm_kering_and_innovation_company_worn_again_join_forces_to_make_the_continual

[vi] http://www.marksandspencer.com/s/plan-a-shwopping

[vii] http://www.kering.com/en/press-releases/hm_kering_and_innovation_company_worn_again_join_forces_to_make_the_continual

[viii] http://edition.cnn.com/2013/04/12/business/second-hand-clothes-africa/

[ix] http://truecostmovie.com/about/

[x] http://www.worldwatch.org/node/810

[xi] https://www.fashionrevolution.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Website_HTBAFR_Booklet_BCxFR_Print.pdf

[xii] https://www.fashionrevolution.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Website_HTBAFR_Booklet_BCxFR_Print.pdf

[xiii] https://www.fashionrevolution.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Website_HTBAFR_Booklet_BCxFR_Print.pdf

It still strikes me as profoundly wrong that even though cotton is the world’s oldest commercial crop and one of the most important fibre crops in the global textile industry, the industry generally fails to focus on the entire value chain to ensure that those who grow their cotton also receive a living income.

Up to 100 million smallholder farmers in more than 100 countries worldwide depend on cotton for their income. They are at the very end of the supply chain, largely invisible and without a voice, ignored by an industry that depends on their cotton.

When it comes to clothing, companies’ supply chain engagement was once limited to who their importer was. Now they are engaging with their supply chain more and have better awareness of the factories used to manufacture their end products. Even before the Rana Plaza disaster of 2013, there had been increased attention on improving the conditions experienced by textile factory workers thanks to campaigns such as the Clean Clothes Campaign.

Some companies also have awareness beyond the factories and these are all movements in the right direction. However, even those mindful of the difficulties faced by factory workers, tend to miss the first links in the supply chain.

Maybe this is because cotton farmers continue to somehow lose out in both the so-called ‘sustainable’ and ‘ethical’ fashion debates. When companies talk about ‘sustainability’ in their clothing supply chains, they are generally looking at the environmental impact of sourcing the raw materials. Meanwhile in ‘ethical’ conversations about the many livelihoods touched by the garment value chain, companies generally refer to factory workers, again overlooking the farmer who grows the seed cotton that goes into our clothing.

The reason we need to keep insisting that cotton farmers are an important part of the fashion supply chain is because cotton is failing to provide a sustainable and profitable livelihood for the millions of smallholders who grow the seed cotton the textile industry depends on. Just as it’s important for us to take home a living wage, to help bring a level of security for our families and the ability to plan for the future, I would argue that this is even more vital for people living in poorer countries where there is little provision for basic services such as health and education or the safety net of social security systems to fall back on.

As a global commodity, cotton plays a major role in the economic and social development of emerging economies and newly industrialised countries. It is an especially important source of employment and income within West and Central Africa, India and Pakistan.

Many cotton farmers live below the poverty line and are dependent on the middle men or ginners who buy their cotton, often at prices below the cost of production. And rising costs of production, fluctuating market prices, decreasing yields and climate change are daily challenges, along with food price inflation and food insecurity. These factors also affect farmers’ ability to provide decent wages and conditions to the casual workers they employ. In West Africa, a cotton farmer’s typical smallholding of 2-5 hectares provides the essential income for basic needs such as food, healthcare, school fees and tools. A small fall in cotton prices can have serious implications for a farmer’s ability to meet these needs. In India many farmers are seriously indebted because of the high interest loans needed to purchase fertilisers and other farm inputs. Unstable, inadequate incomes perpetuate the situation in which farmers lack the finances to invest in the infrastructure, training and tools needed to improve their livelihoods.

However research shows that a small increase in the seed cotton price would significantly improve the livelihood of cotton farmers but with little impact on retail prices. Depending on the amount of cotton used and the processing needed, the cost of raw cotton makes up a small share of the retail price, not exceeding 10 percent. This is because a textile product’s price includes added value in the various processing and manufacturing activities along the supply chain. So a 10 percent increase in the seed cotton price would only result in a one percent or less increase in the retail price – a negligible amount given that retailers often receive more than half of the final retail price of the cotton finished products.

Within sustainable cotton programmes, Fairtrade works with vulnerable producers in developing countries to secure market access and better terms of trade for farmers and workers so they can provide for themselves and their families.

Our belief is that people are increasingly concerned about where their clothes come from. This year we visited cotton farmers in Pratibha-Vasudha, India, a Fairtrade co-operative in Madhya Pradesh. We saw the safety net that Fairtrade brings; the promise of a minimum price that works in a global environment. The impact on prices of subsidised production in China and the US adds to unstable global cotton prices. These farmers democratically decide how the Fairtrade Premium is spent: on training to improve soil and productivity, strategies to mitigate the impacts of climate change and on the most important ways for their communities to benefit, such as building health centres and educating children.

Consumers want their clothes made well and ethically, without harmful agrochemicals and exploitation. We think about farmers when we talk about food. Let’s start thinking about farmers when we think about clothing too.

Image credits: Trevor Leighton.

Saturday 9 May 2015 is World Fair Trade Day #WFTD2015

This storyboard by Khushboo Wadhwani beautifully presents the routine of making block print cloth in India. The brief was to show the production process and the skills involved, rather than focussing on the people.

Fair Trade is a tangible contribution to the fight against poverty, climate change and global economic crises. The World Bank 2014 Report shows that more than one billion people still live at or below $1.25 a day.

The World Fair Trade Organization (WFTO) believes that trade must benefit the most vulnerable and deliver sustainable livelihoods by developing opportunities especially for small and disadvantaged producers. Recurring global economic crises and persistent poverty in many countries confirm the demand for a fair and sustainable economy locally and globally. Fair Trade is the response.

CREDITS

Footage:

Indiaroots.com

Good Earth India

Bollywood! Boclive (Lakme Fashion Week footage)

Music:

Tony Anderson: Breakthrough

Friday marked the two year anniversary of the devastating collapse of Rana Plaza garment factory in Bangladesh. It also marks the second Fashion Revolution Day, launched last year to commemorate the Rana Plaza disaster with the aims of encouraging greater collaboration across the fashion sector supply chain.

The Rana Plaza disaster has been said to be a “wake up call”, an “eye opener”, a “game changer” and the “end of business as usual” in the global garment supply chain. It has indeed changed the garment industry landscape in Bangladesh and led to many improvements in the fashion supply chain. Western clothing companies, trade unions and the Bangladeshi government have taken steps to improve workplace safety. The legally binding Accord on Fire and Building Safety, run by European brands and retailers, and the Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety, led by North American retailers, were formed to ensure safer working conditions at the bottom of the supply chain. A series of inspections in Bangladeshi factories are being conducted, contributing towards better working conditions in Bangladesh and hopefully across fashion supply chains worldwide.

While these developments are encouraging, more needs to be done to accelerate efforts to tackle safety hazards in the factories of low-cost manufacturing countries.

Sedex data shows that more than half (52%) of all issues raised in ethical audits on the Sedex system globally over the past two years are related to health and safety. The highest risks in the garment sector in Bangladesh are related to fire safety: 25% of audits on the Sedex system show problems with fire safety in Bangladesh. Fire safety concerns are also at the top of risks in other garment-producing countries – Pakistan (19%), China (18%) and India (17%) – endangering the lives of workers and posing a big risk to brands, suppliers and investors. Other major risks include building safety, labour rights, working hours, machinery and lack of personal protective equipment & clothing.

The Bangladesh Accord looks predominately at fire and building safety in Bangladesh, but fashion supply chains are affected by many other issues. Garment workers in Bangladesh face poor working conditions and issues around freedom of association, according to the latest report by Human Rights Watch. Countries need to effectively enforce labour laws and ensure that garment workers are able to voice their concerns about safety and working conditions, without fear of being fired, intimidated or assaulted. There is also need to investigate unfair labour practices and ensure workers are paid a living wage.

The garment, textiles, clothing and footwear industry is among the most labour intensive industries, estimated to employ more than 60 million people worldwide. In Bangladesh alone there are more than four million garment workers. But the costs for garment production in Asia are rising, and the garment industry is increasingly moving to other regions, for example Africa. As these new markets are preparing for an influx of new business – building new factories to employ a huge amount of local people – it is crucial to ensure that safety requirements are built in from the very beginning.

The global fashion industry has the power to change its supply chain and positively impact working conditions. Collaboration is key here, amongst Sedex global community we see real progress when buyers and suppliers collaborate between all levels of the supply chain. Leading companies are looking beyond the usual boundaries of responsible sourcing to consider the wider context around responsible sourcing challenges. For example, Marks & Spencer is going outside its factories into communities, working towards empowering women and improving livelihoods of workers.

Change is happening, slowly but steadily. Collaboration among companies, government and, NGOs is essential in delivering improvements in working conditions and ensuring workers well-being throughout global supply chains.

In 1908, 15,000 women marched through New York City to demand shorter working hours, better pay and voting rights. This was the beginning of a movement from which International Women’s Day was born. Decades later, in 2011, the United Nations marked the 11th of October as the first International Day of the Girl Child, highlighting the continuing challenges which young girls still face in communities across the globe; especially in relation to accessing education, being safe from violence and exploitation. Within the fashion industry, the pressure to meet the demands of conventional fast fashion companies is enormous. To stay competitive, manufacturing factories keep their overheads low by paying low wages for workers. Child labourers can be paid even less and are an attractive proposition for employers. Parents are forced to send their children, including young girls to work in conditions which are unsafe in order to create enough income to sustain the family.

As a Fair Trade company, People Tree works with many social businesses who not only create decent employment and pay fair wages, but who also invest in their local community. For example, by funding schools, medical support and awareness raising on the rights of women and girls. We support communities in India, Bangladesh and Nepal who empower girls by giving them access to education and vocational training. By focusing on empowerment of women through dignified and artisanal work, we help keep handicraft traditions alive, as well as offer opportunities to help strengthen these communities and continue to support their learning and development. Equal opportunities are reflected throughout People Tree’s supply chain, where 56% of leadership roles are held by women.

In rural Bangladesh, girls are often not given opportunities to go to school, instead they are encouraged to stay at home to help around the house and to get married very young. People Tree works with Swallows, an NGO set up to empower the poor and underprivileged population, especially women, in the village of Thanapara. Swallows runs a handicrafts program which makes beautiful hand woven and hand embroidered garments. This business helps to fund Swallows’ development work in the local area, and the empowerment of girls and women is central to their work.

Mrs Gini Ali, Assistant Director at Swallows, feels that discrimination and lack of opportunity for women in Bangladesh are the biggest barriers to improving living conditions there. She says:

“The Fair Trade principles applied by People Tree have created economic stability for Swallows, allowing it to become an independent organisation, this has led to the empowerment of the women of Thanapara.”

Swallows funds schools and awareness raising to ensure that girls have the same chance to study as boys. They raise awareness amongst parents, sharing the importance of education for young girls and its benefits for the family and the community. As well as sharing the importance of education, Swallows raises awareness around the issue of child marriage and the negative impacts this can have. Swallows provides free training opportunities for young women and also sponsor young women to study part time whilst the work part time making Fair Trade clothing. As well as this they offer legal support to local women who are victims of domestic violence and raise awareness locally on the issue.

In Nepal, People Tree partners with Kumbeshwar Technical School (KTS). Originally set up as a vocational training centre, KTS has now developed into a Fair Trade business creating beautiful hand knitted products. Established in 1983 with the goal of breaking societal barriers created by Nepal’s caste system, KTS was set up to help Pode people, the so-called ‘untouchable’ caste in Nepal. Those born into the Pode caste are expected to clean the sewers and streets of the areas inhabited by higher castes for no more than scraps of leftover food. The discrimination which keeps these people out of other forms of work even affects children, who may drop out of primary school because they are unable to fit in. Until recently, Pode children did not go to school at all.

KTS now offers employment to 2,273 women who come from economically disadvantaged backgrounds. On top of this, the profits from Fair Trade helps fund vocational training; a school; a day care centre for over 250 children from low income families and an orphanage.

Both KTS and Swallows are both ‘Guaranteed Fair Trade Organisations’ by the World Fair Trade Organisation (WFTO). This recognises that the whole of the company is 100% dedicated to Fair Trade and ensures that all the groups adhere to the WFTO’s 10 Fair Trade Principles. Key to these 10 principles is Principle Six: ‘Commitment to Non Discrimination, Gender Equity and Women’s Economic Empowerment’. At People Tree we believe that Fair Trade business is a key driver in the empowerment of women and girls worldwide.

For more information about how People Tree supports women and girls, please contact us for a copy of our Social Review and read about People Tree’s latest Campaign Against Child Labour in our digital edition of the Eco-Edit: http://www.peopletree.co.uk/eco-edit