At the Copenhagen Fashion Summit last week, Juan Orlando Hernández, President of Honduras, issued the following invitation: ‘If you would like to go to Honduras to look around for yourselves, I will be personally at the airport waiting for you’.

Ignoring the heckler at the back of the room who called out ‘Mr President, stop the military from murdering community activists’ the President of Honduras launched into a promotion for his country as a leading garment exporter to the US and his ambitions for a larger European market share. The garment and textile industry is part of the newly launched Honduras 2020, a $3.4 billion project which aims to make Honduras into the country of choice for brands and retailers wishing to source sustainably. ‘We will do this through a real sustainable model focussing on key topics such as sustainable working conditions, protecting the environment, using the latest technology to reduce consumption of resources, moving from fossil fuel to renewable energy sources’ stated Juan Orlando Hernández, who continued by highlighting his country’s ambition to source 80% of its energy from renewable sources by 2020.

The commitment to reduce fossil fuels clearly doesn’t extend to the President himself, who rented a luxury jet to fly to the conference from Vista Jet, whose clients include celebrities such as Beyonce and the Beckhams. The President’s short presentation would have cost $360,000 in travel alone, according to one source, prompting dozens of critical comments on the Copenhagen Fashion Summit Facebook page.

The President continued to address the 1200-strong audience by underlining how seriously his country takes the social side of sustainability. ‘We enjoy an excellent and safe work environment and taking care of our people is our main focus and our responsibility’.

The President went on to say that Honduras was ‘the second most fair location for garment production’. After an investigatory email to the Americas Apparel Producers’ Network, I received a response from Managing Director Mike Todaro who clarified that the President was referring to the The AAPN Asia/Americas Report Card. Honduras came 2nd overall in the AAPN Report Card which is completed by sourcing executives. However, as far as I can see from online information about the Report Card, only one out of the 8 criteria relates to social compliance/sustainability and the other 7 include elements like cost, speed and product development.

According to War on Want 53% of garment workers in maquilas, or garment factories, in Honduras are young women from deprived backgrounds who have little education. Most are unaware of their rights, exploitation is widespread and workers are actively discouraged from joining unions. The Solidarity Center says trade unionists are routinely threatened, intimidated, harassed and even murdered, with the criminals rarely brought to justice.

31 trade unionists have been assassinated and 200 injured in attacks since 2009, according to the umbrella federation for US unions AFL-CIO. In fact, in March last year the US Department of Labour issued a damning 143 page report documenting widespread and serious violations of labour rights in Honduras. The report detailed numerous cases where Honduran employers engaged in acts of anti-union discrimination, imposing non-union pacts to frustrate collective bargaining, as well as cases of non-payment of wages, forced overtime and numerous occupational health and safety violations.

On average, the wages earned in maquilas are equivalent to only 37% of the cost of the basic basket of consumer goods in Honduras. Moreover, the gap between wages for workers in maquilas and those in other industries is widening. The race to the bottom will continue unless we take a systemic approach to the issue of a living wage by working with governments and unions to set a legal, enforceable minimum wage in their country which ensures workers can meet their basic needs.

Without supply chain transparency and a commitment from fashion brand owners and factories to invest in better working conditions, living wages and workers’ rights, garment workers will remain disempowered and unable to independently negotiate labour conditions.

The garment and textile industry has undoubtedly brought jobs to the country, but not necessarily good jobs. It is often argued that any job is better than no job, but there is no reason why we can’t be creating decent jobs, jobs with dignity, without any significant impact on the retail price. The fact that people are desperate isn’t an excuse to exploit them. A Fashion Revolution is needed because brands, even the best of the brands who are working most proactively towards a living wage, will never change the system.

‘You should come see if this jobs really help people get out of poverty, with the kind of wages they make, with no labor rights. They are not even given a place to have their meals, they have to take lunch in the street and then come in back to work! Did you really believe what this man went to say to your event!’ commented RS Bruise on the Copenhagen Fashion Summit Facebook page.

So, in response to RS Bruise and all the other Honduran citizens whose commented on the visit of Juan Orlando Hernández to the Copenhagen Fashion Summit: Yes, we will come and see for ourselves #whomademyclothes. We will come and see whether Honduras really is one of ‘most fair social locations in the Western hemisphere for garment production’, as claimed in the President’s presentation.

I am ready to take the President of Honduras up on his offer to visit garment factories in his country and trust that he will keep his word. Meet me at the airport, Mr President.

24 April is the most important day for fashion. But not because it’s Fashion Revolution Day. It’s because over 1000 men and women, with families, hopes and dreams just like us, lost their lives while making our clothes.

Did you know that 80% of our fashion is made by 18-24 year old young women around the world? Sadly the only time we hear about these millennial makers is when tragedies such as Rana Plaza occur.

When we ask more about them, we can change their lives. Let’s never forget Rana Plaza and keep asking our favourite brands #whomademyclothes?

80% of our fashion is made by women (mostly 18-24 years old) but we only hear about these millennial makers when they’re associated with a tragedy like Rana Plaza in Bangladesh in 2013 or the infamous Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in New York in 1913. Their stories are eclipsed by heartbreaking headlines that hound the fashion industry.

But there is another part of this story. It’s a story of hope. Remake has traveled to factories and dormitories throughout the world in search of the women who never make the headlines. Kashmiri who opens the yarn to make it into fabric. Maud and Rubina who stitch our blouses and jeans together. Anju who pulls out loose threads and inspects everything to ensure perfection. Each has a story and a hope for a very different future.

Meet the women behind fashion’s supply chain — we followed them from Haiti to Pakistan to China — and asked each of them to share a message to you, the end shopper. These are their stories:

Kashimiri, Yarn opener, Panipat, India

I am 25 years old and already have 4 children. I sit crouched on the floor all day, opening spindles of yarn which go on to become fabric. Panipat has a lot of needs. Open sewers, flies and trash everywhere. Only recently my children starting going to school. I now hope that they will have a better future. Go on to be somebody. I hope you can see their faces in the threads of your fabric.”

Rubina, Hoodie Sewer, Karachi, Pakistan

I am 22 years old and wanted to be a doctor. Then my father got sick, so here I am, many years later, still at a factory stitching college sweatpants and hoodies that go to America. I don’t want you to feel sorry for me. I used to be shy and scared in the factory environment. But after all the injustices I’ve seen happen here, I’ve become a labor organizer. I go to management to demand that we are not harassed, paid on time, given proper food to eat. You would not believe the things I have seen. Stitching all day long my mind wanders and I think about you often. You having fun, wearing these hoodie on campus. I wonder if you think about me ever? The woman who made that for you. I am taking English classes at night. So that one day I can at least get an office job.

Maud, Jeans Sewer, Ouanaminthe, Haiti

The factory across from the Massacre river is like paradise, with its lush green trees and paved roads. I’ve been sitting down sewing your jeans here for five years. Recently my back and neck has been hurting a lot more. But without this job, I have no way to support myself or my six siblings. After a long day, I walked across the river into my community which is pitch dark at night. There is no electricity or running water, just human need everywhere. I want to save enough to go back to university and study computer science. I want you to think about your sister Maud in Haiti, when you put on your jeans. On dark sad nights I play on Facebook with my phone and dream of the day I can be just like you.

Zheng Ming Hui, Quality Assurance, Guangzhou, China

At 19 I left my village to experience the excitement of city life. Here I am three years later, still at the same factory. I work 12 hours a day, looking at beautiful, bright patterns to make sure that there are no defects. My mother wishes I would call her more. But mostly I miss my grandmother. I only get to see my family once a year for Chinese New Year and mom makes the biggest feast. My entire life is the factory. I live in the dorms with three roommates, work all day only stopping to eat at the cafeteria. On my one day off, I am too tired to do much so I play with my phone. At night I dream of bungee jumping. I want to find someone to fall in love with and travel the world for work, taking pictures and telling stories. But for now, I am here, making sure your clothes look nice. I picture you and I am sure you look BEAUTIFUL!

Anju, Fabric Inspection, Delhi, India

I once dreamed of a life that was very different. Where I could finish my education and become a teacher. Everything changed when I was 15 and married to a man with few means. For the last 10 years, I’ve been working in a factory instead. I am proud to be an equal bread winning partner with my husband and to know that my hard work allows my children to go to school. I stand on my feet all day, pulling loose threads out of finished blouses and tops. Making sure they are perfect for you. I want you to know that I recently took a health education course on making nutritious meals with little money. I now teach what I’ve learned at my children’s school on my day off. I guess my dream of becoming a teacher has come true after all.

A 100 pair of human hands touch our clothes before they get to us. Each one of these mothers, sisters, wives and daughters are fierce and hard-working. Dreaming like us to be healthy, happy and financially secure.

Share these stories on Twitter and Facebook with your favorite brands and say: I want to know the invisible people #whomademyclothes.

Together we can #remakeourworld

Moral. It’s not a word we use very often, especially when we talk about fashion. Fashion comes with many adjectives attached: fabulous, iconic, elegant, sumptuous, dashing, nostalgic, effortless… but moral is rarely one of them.

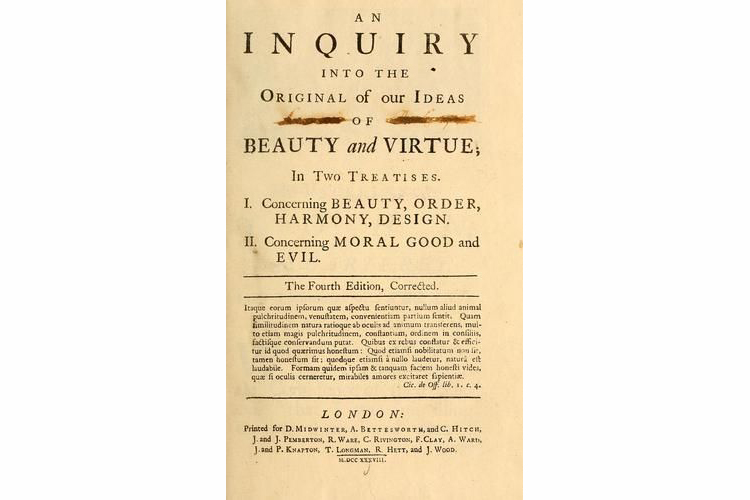

In 1725, Rev Francis Hutcheson wrote An Inquiry into the Original of our Ideas of Beauty and Virtue. In his opinion, an outward perception of beauty was impossible without an inner sense of beauty as well. He called this as a ‘moral sense of beauty’ and, importantly, he understood it as something which could be altered by information and reasoning.

In the mid 18th Century, the first examples of fashion press appeared in Paris with publications like Le Journal de la mode et du Goût. This was the start of the connection between fashion and taste, fashion and ideals, fashion and individualism. It was also the beginning of our moral disengagement as community values gave rise to individual values. The fashionable young women portrayed on its pages embodied the rise of consumer culture.

This desire for new clothes was not confined to 18th century Europe. In Latin America, clothing was recognised as a symbol of social status and prestige and was manipulated by the marginal sectors of society in order to become more socially, economically, politically and culturally reconised.

An overwhelmed husband wrote to the Mercurio Peruano in 1791 setting out the precarious financial situation in which he found himself as a result of his wife’s fashion taste. He protested her need to have a different dress for every social occasion. Whilst his wife had garnered admiration from society in Lima, the husband was unable to pay his debts. For the wife mentioned in the letter, clothing had become a vehicle to make herself visible in a male-dominated society, expressing her status and social freedom.

Our desire for fashion has certainly not diminished in the ensuing 200 years. What has changed, however, is our proximity to, and awareness of, the impact of our purchases.

In the 19th Century, a sweater was an employer or middleman who abused his workers with monotonous work, unhealthy or unsafe conditions and poverty-level wages. The desire of manufacturers to pay the lowest possible wage, coupled with a huge number of rural poor and immigrants looking for work in Britain and the US, produced a climate ripe for the exploitation of workers and the establishment of the first sweatshops. Sweating came to describe work which lacked respect for the human factor. A House of Lords Select Committee on the Sweating System was established in 1889 which publicly exposed the poor conditions in which garment workers toiled. Debate over the morality of production led to unionisation and concerned consumers called for reform. For a while, things got better.

The 20th Century saw waves of trade liberalisation policies starting after World War II, resulting in the offshoring and outsourcing of production to Asia and Latin America. With the relocation of manufacturing came the abrogation of responsibility. It has been endlessly debated whether brands and retailers are morally and legally responsible for their workers overseas.

It has also been questioned whether the fashion consumer in the West is morally responsible for the poor working conditions and unsafe working practices in factories in developing countries. Many of us suspect that the clothes we wear have been made in a sweatshop. Does this affect our moral responsibility? In his book Profits and Principles: Global Capitalism and Human Rights in China, Michael A Santoro argues that ‘consumers are a very big part of the web of moral responsibility for human rights. Ultimately it is consumers who wear the shoes and clothes manufactured in sweatshops… What is needed is a real partnership between companies and consumers, based on a very simple moral compact. Companies must agree to manufacture products in compliance with human rights codes and consumers must agree to place monetary value on such compliance. Both sides of the compact are necessary to safeguard human rights’. In other words, equity for all must become a universal standard and we all bear responsibility for ensuring this happens.

My relative Dyddgu Hamilton (pronounced Dithky) was a close friend of Hilaire Belloc and his wife Elodie. Dyddgu became Belloc’s secretary and subsequently his lifetime correspondent – there are hundreds of letters between them.

I’ve been a voracious Belloc reader for many years – he was a prolific writer with well over 100 published books. I recently came across this quote he wrote in the Sahara, and it struck me that the description of the barbarian could so easily apply to the fast-fashion addict who takes no responsibility and gives no thought to their expanding wardrobe.

‘The Barbarian hopes – and that is the mark of him, that he can have his cake and eat it too. He will consume what civilization has slowly produced after generations of selection and effort, but he will not be at pains to replace such goods, nor indeed has he a comprehension of the virtue that has brought them into being…. We sit by and watch the barbarian…We are tickled by his irreverence ..we laugh. But as we laugh we are watched by large and awful faces from beyond, and on these faces there are no smiles.’

Returning to Frances Hutcheson’s philosophy of beauty, his views are reflected in the worldview of indigenous peoples in the Andes where something which is beautiful is typically something which is well-balanced, something ayni. Everything in the Inca world was based on ayni, a system of exchange based on mutual respect and justice with other communities and cultures throughout their vast empire. Ayni has survived the conquest and capitalism and is still widely practised today. Beauty is about balance, and what is sustainability if not finding a balance between the desires of our generation and the needs of the next?

Before we can rediscover a ‘moral sense of beauty’ on falling in love with a new dress, we need to know that there is equity behind its beauty. To know that there is equity, we need transparency. We cannot hold the many stakeholders in the fashion supply chain to account until we can see them, and we cannot start to tackle exploitation until we can see it. That’s why Fashion Revolution is asking the question #whomademyclothes. We want to know that the clothes we buy are beautiful in every way.

Six years after a major earthquake devastated the Haitian capital and its environs and the international community promised to “build back better,” Haitian workers say their daily lives are a struggle for survival, with their meagre wages insufficient to cover basic expenses.

In recent interviews, Haitian garment workers told the Solidarity Center that they are worse off today than before the quake. With prices rising and wages largely stagnant, their paychecks do not allow them to support themselves and their families.

“We spend almost our entire daily wage on food and transportation,” said one garment worker interviewed. “We cannot save any money and we do not have enough money to get health care or education. Our future is compromised.”

Another worker said he sometimes has to borrow money to “make sure that at least the family has something to eat.”

Haiti is the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere and one of the poorest in the world. According to the World Bank, more than 6 million of Haiti’s 10.4 million people (59 percent) live under the poverty line.

Haitian garment workers hold rare full-time jobs in an economy that is largely informal, and work for profitable multinational manufacturers, some incentivized to come to Haiti and create jobs after the quake. Yet garment-sector wages are legally set below the national minimum wage and well below what is necessary to cover basic costs. A December 2015 Solidarity Center analysis of living expenses found that the average garment worker spends 160–225 Haitian gourdes ($2.80 – $3.94) a day on food and transportation for herself, and another 395 gourdes ($6.91) on food for the household. The current minimum daily wage for garment workers, who work 48 hours a week, is 225–240 gourdes ($3.94–$4.20). The minimum wage is supposed to increase this spring, to $5.11 for an eight-hour shift.

In 2013, Haitian workers and their unions waged rallies and protests to demand that the daily minimum wage be increased to 500 gourdes ($8.75) for export apparel workers. The government set the wage at less than half of that. In 2014, the Solidarity Center found that a living wage of 1,000 gourdes per day would allow workers to meet their basic needs.

“As we mark this grim anniversary, we have to ask why the people best-positioned to revive the Haitian economy—hardworking Haitians—are handicapped by abysmal and degrading wages. Until Haitians can earn a living that allows them to do more than barely survive, there will be no real recovery,” said Shawna Bader-Blau, executive director of the Solidarity Center. “The international community and Haitian government should be ashamed of policies that guarantee poverty wages and grant concessions to multinational corporations instead of providing real opportunities for Haitians workers to improve their lives and livelihoods and build a better country for themselves and their children.”

The three-year anniversary of the November 24, 2012, fire that killed 112 Bangladesh garment workers at the Tazreen Fashions Ltd., factory offers a time to reflect on garment workers’ ongoing struggle for workplaces where they will not be killed or injured and for jobs that will support their families.

The Tazreen fire was preventable, as was the collapse of the multistory Rana Plaza factory five months later in which more than 1,130 garments workers died and thousands more were severely injured.

Workers at Tazreen and Rana Plaza did not have a union or other organization to represent them and help them fight for a safe workplace. Without a union, garment workers say they are harassed and even fired when they raise safety issues with their employer. They are not trained in basic fire safety measures and often their factories, like Tazreen, have locked emergency doors and stairwells packed with flammable material.

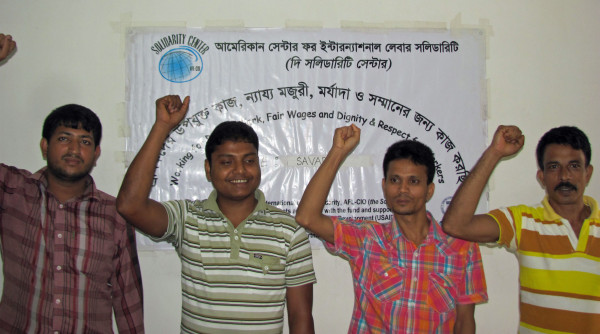

Despite the many obstacles to forming organizations and achieving a voice at work, garment workers are at the forefront of pushing for change at their factories. With our strong and long-term grassroots connections in Bangladesh, the Solidarity Center allies with garment workers to provide ongoing training for factory-level union leaders on topics such as gender equality, workers’ legal rights and fire safety.

This photo essay gives voice to the sorrow, but also the hope, of the 4 million workers who toil in Bangladesh garment factories.

1. Bangladesh’s 4 million garment workers, mostly women, toil in 5,000 factories across the country, making the $25 billion garment industry the world’s second largest, after China. Yet many risk their lives to make a living. In the three years since the fatal Tazreen Fashions Ltd. factory fire, some 31 workers have died and at least 935 people have been injured in garment factory fire incidents in Bangladesh. Credit: Law at the Margins

2. Some 112 garment workers were killed in a blaze that swept through the Tazreen factory on November 24, 2012. Hundreds more were injured and like Tahera (above), will never be able to work again. Survivors say they endure daily physical and emotional pain, and often cannot support their families because they cannot work and have received little or no compensation. Solidarity Center/Mushfique Wadud

3. Tens of thousands of Bangladesh garment workers held rallies on May Day this year to highlight the need for the freedom to form worker organizations to ensure safe and healthy workplaces. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

4. With few jobs available that pay a living wage, more than 600,000 Bangladeshi workers migrate each year. Yet, “after two years, after three years, they are not getting their salary,” says Sumaiya Islam, director of the Bangladesh Migrant Women’s Organization (BOMSA). “After spending $1,000 (to labor recruiters), they are not getting paid.” Credit: Shahjadi Zaman

5. Migrants from Bangladesh also risk their lives when going overseas for jobs. In June, Bangladesh families rallied to demand the government punish traffickers after many Bangladesh workers were among migrants stranded on abandoned boats by unscrupulous labor traffickers. “I did not get anything to eat for 22 days and just survived by eating tree leaves,” Abdur said, describing his journey to Malaysia. Credit: Solidarity Center/Mushfique Wadud

6. On April 24, 2013, the multistory Rana Plaza factory collapsed, a preventable tragedy that killed more than 1,100 garment workers and injured thousands more. On the two year anniversary in April, family members and friends gathered at the site of the building to commemorate their loss. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

7. Thousands of garment workers, like Mosammat Mukti Khatun (above, looking at the Rana Plaza rubble) who survived the Rana Plaza disaster, remain too injured or ill to work and support their families. Survivors and the families of those who lost loved ones in the collapse say they are struggling to make ends meet, unable to pay rent, send their children to school or provide for other basic needs. Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

8. Days before tens of thousands of Bangladesh garment workers rallied on the two-year anniversary of the Rana Plaza collapse, the ITUC released a report that found “a severe climate of anti-union violence and impunity prevails in Bangladesh’s garment industry. The violence is frequently directed by factory management. The government of Bangladesh has made no serious effort to bring anyone involved to account for these crimes.” Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

9. The Solidarity Center launched the Bangladesh Worker Rights Defense Fund in April 2014, following an increase in violence and harassment against workers who were seeking to form unions to protect their health and rights on the job. Donations of more than $15,500 helped to provide costly medical treatment for organizers beaten or attacked while speaking to workers about their rights, and temporary food and shelter for workers fired for trying to improve their workplace. Credit: Solidarity Center/Shawna Bader-Blau

10. Despite employer and government resistance to workers’ efforts to form organizations to improve job safety, in the Dhaka export processing zone alone, 40 of the 103 factories include workers’ welfare associations, which are similar to unions. Credit: Solidarity Center/Mushfique Wadud

11. Women garment workers primarily fuel Bangladesh’s $25 billion a year garment industry, yet women are “still viewed as basically cheap labor,” says Lily Gomes, Solidarity Center senior program officer for Bangladesh. “There is a strong need for functioning factory-level unions led by women,” says Gomes, who is leading efforts to help empower women workers to take on leadership roles at factories and in unions throughout Bangladesh. Credit: Solidarity Center/Kate Conradt

12. With strong and long-term grassroots connections in Bangladesh, the Solidarity Center provides ongoing training for garment worker union leaders on topics such as gender equality, workers’ legal rights and job safety. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

13. Garment worker union leaders sharpen their skills through regular Solidarity Center workshops, such as this one on financial management. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

14. Hundreds of garment worker union leaders have participated in this year in the Solidarity Center’s 10-week fire safety certification course. “People who worked at Tazreen and Rana Plaza had no training and had no union,” says Saiful, who took part in a recent fire training. “This training is about making sure those things never happen again.” Credit: Solidarity Center/Rakibul Hasan

The “Made in Jordan” label is familiar to people shopping for shirts, jeans and other clothes. Mervat Jumhawi, a Jordanian union organizer, is actively ensuring the largely migrant workforce that cuts and sews these garments does so in safe conditions, receives fair wages and is treated with respect on the job.

“I was a garment worker and I know what exploitation is. I know what that means,” says Jumhawi.

After working 13 years in textile factories, Jumhawi spent six years on the board of the General Trade Union of Workers in Textile, Garment and Clothing Industries, where she served until recently. The union represents all 55,000 textile workers throughout Jordan, including migrant workers who comprise 71 percent of the country’s garment factory workforce.

Garment exports, produced primarily for the United States, account for some 20 percent of the country’s gross domestic product, with factories located in the Sahab, Dulail and Ramtha industrial zones.

“In the beginning, I was not familiar with migrant worker issues,” Jumhawi says, speaking through a translator. “But after I worked with migrant workers, I was more interested in their issues because they are more marginalized and vulnerable.”

Migrant Worker Exploitation Begins in the Home Country

Exploitation of migrant workers in Jordan and other countries around the world often begins in their home countries, where they typically pay huge fees to labor brokers for a job. Indebted when they start their employment, migrant workers often endure abusive conditions to pay off their loans. Employers also may confiscate passports, effectively holding migrant workers hostage and unable to leave if they are not paid or if they experience verbal or physical abuse. Jumhawi helps raise workers’ awareness of their rights under the law and assists workers who are not receiving health care, who have been abused or otherwise need assistance making their way through the legal system.

More than 70 percent of migrant textile workers in Jordan are women, primarily from Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Myanmar. Jumhawi’s one-on-one assistance with garment workers and her dedication to improving their working conditions—she spent 40 days and nights with 1,300 striking Burmese garment workers—has generated tremendous trust among the workers.

In one instance, when Bangladesh and Sri Lankan workers went on strike in 2013, Jumhawi tried to speak with managers, but they would not let her in the factory. As she left, she looked back, and saw hundreds of workers following her. Her challenge to management gave the workers strength, she said. Seeing the workers take off with Jumhawi in the lead, managers ultimately negotiated—but not until Jumhawi had talked with each worker to hear specific grievances.

Solidarity Center Support Assists Migrant Workers

The Solidarity Center provided support over the past year for the migrant outreach project among textile workers, holding trainings on combating labor trafficking and exploitation through collective worker action. Workers were encouraged to form committees to monitor labor rights violations and refer them to the union resolution.

Over the years, the Solidarity Center also has worked closely with the garment workers union, and in May 2013, the union negotiated a contract with employers that covers all textile workers, including migrant workers. The contract set up health and safety committees, requires employer pay for transportation and food and prohibits labor recruiters in origin countries from charging fees to workers.

“Our union is keen on migrant worker issues from the moment they arrive in Jordan,” says Fathalla Al Omrani, garment workers’ union president.

Migrant workers are housed in employer-owned dormitories, which often fail to meet safety and health standards, according to Sara Khatib, a Jordan-based Solidarity Center program office for anti-trafficking initiatives. The contract requires employers follow Ministry of Health standards for living conditions, such as not overcrowding workers in a room.

“We were 10 to 12 women living in one room,” says one garment worker. “After the inspectors visit, the numbers decreased to six or seven.”

‘I Will Struggle for Migrant Workers to the End’

Supervisors yell at the workers if they don’t reach the production target and may deduct pay or even deport them, says Jumhawi. Such actions violate Jordan’s labor laws and the union contract.

Jumhawi has been instrumental in helping workers enforce the contract and seek justice under Jordan’s labor laws. She also recently assisted with production of a video documenting migrant workers’ struggles in Jordan and the role of union strength in helping workers achieve their goals. When asked about her most important victories, she says she counts “every single and small achievement,” as a major success, “even helping a worker with a small thing.”

“Mervat is very close to the workers and they all trust her,” says Khatib, who works closely with Jumhawi. “She follows up on the workers’ cases seriously and she deeply cares about them. She’s a hard working woman and a real unionist.”

Jumhawi works 12 hour days, seven days a week, unless she is too tired or sick, she says. Sometimes the long hours and tough demands make her want to leave the job. But she changes her mind when she thinks of the workers.

“I will struggle for migrant workers to the end, and I encourage all workers, especially women, to become unionists. When I became member of the union, I became stronger.”

Find out more at: http://www.solidaritycenter.org/