I was working with the Fashion Revolution team yesterday at London College of Fashion. I needed a swimsuit for my upcoming Zoology research trip to the Bahamas and heard that AURIA swimsuits were for sale at the EMG Progressive Fashion Concept Store in Beak Street, Soho, just a few blocks away. I found the perfect swimsuit! As it’s Fashion Revolution Week, I of course had to ask the question #whomademyclothes?

AURIA’s swimsuits are made from Econyl.

According to their website ‘the innovative ECONYL® Regeneration System is based on sustainable chemistry. With this process, the nylon contained in waste, such as carpets, clothing and fishing nets, is transformed back into raw material without any loss of quality.

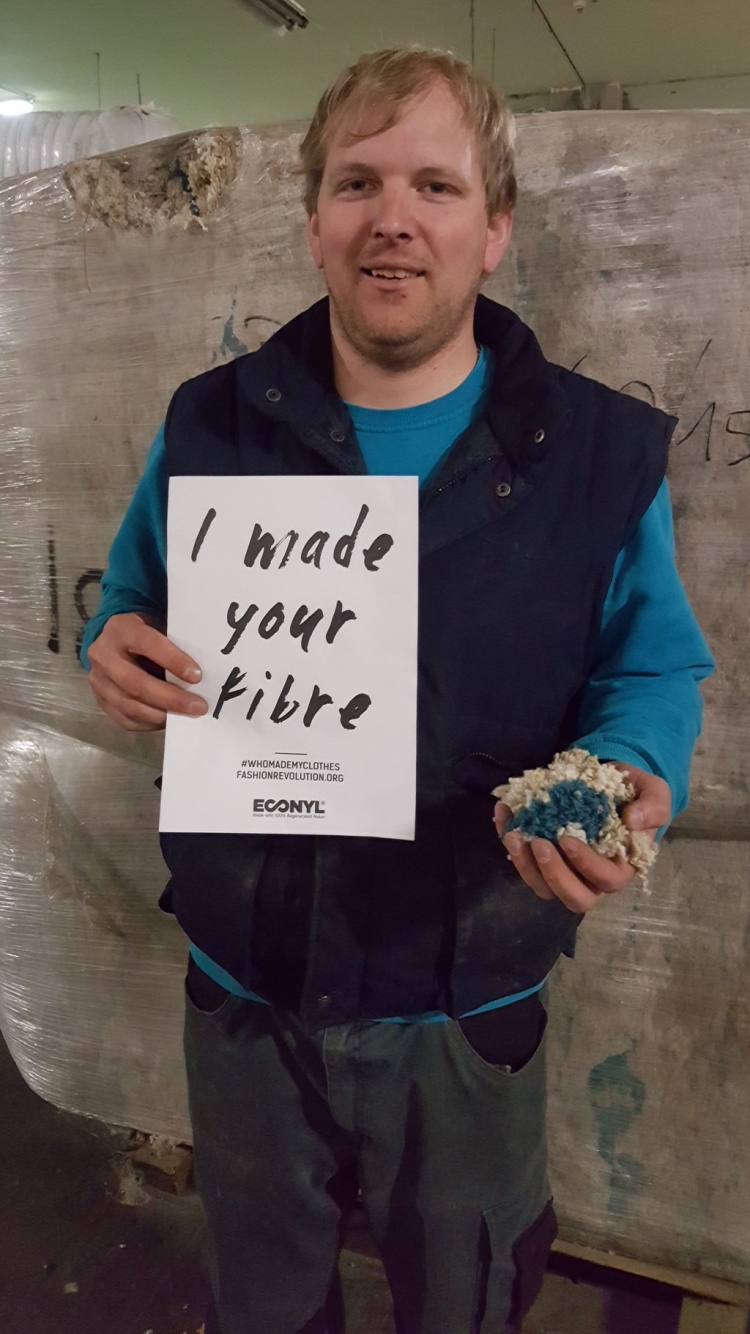

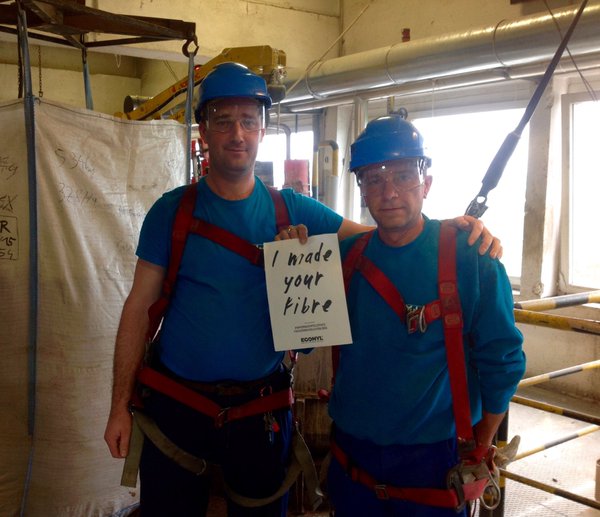

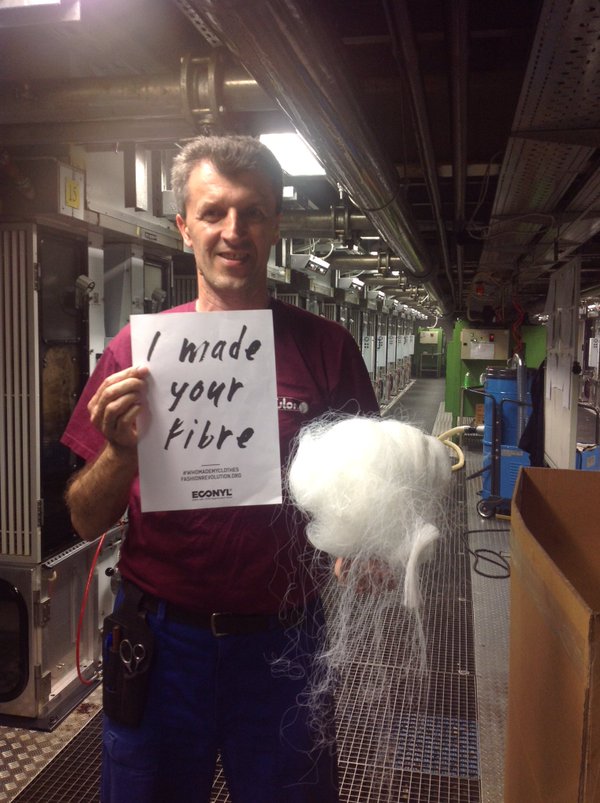

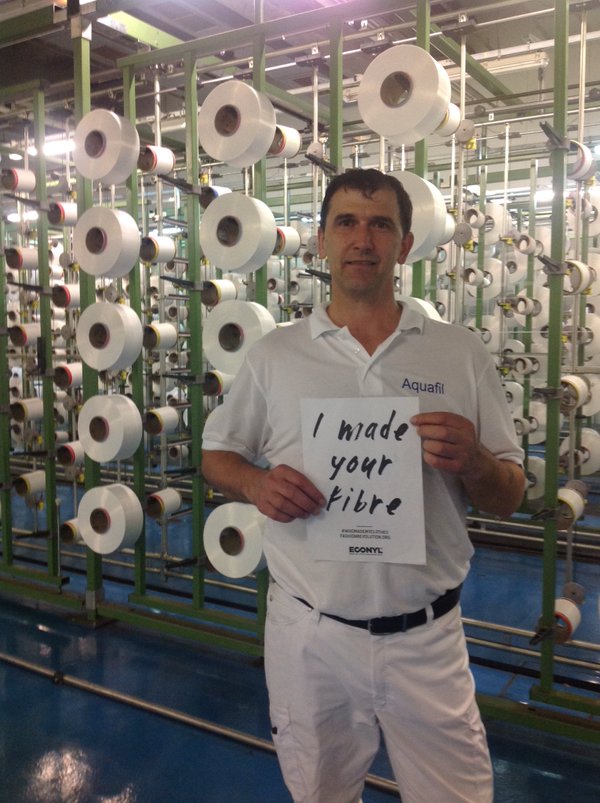

And here are the people who made my swimsuit …

This is Paolo in the ECONYL plant He prepares nets for regeneration

This is Ivo with some nets to be turned into ECONYL yarn

Jan with some carpet fluff, the upper part of old carpets that is regenerated into ECONYL yarn

Denis & Mladen they are at the very beginning of the ECONYL regeneration process

Jozica works in the chemical lab. She checks the waste material that will become ECONYL yarn

Mirko keeps an eye on the spinning to get the best quality ECONYL regenerated yarn in Slovenia

You can always find Boro around the bobbins of ECONYL regenerated yarn to check quality

Bobbins of ECONYL regenerated yarn wouldn’t get to clients if it wasn’t for Muamer

And all of this recycled fibre then gets made into gorgeous AURIA swimsuits

I’m really happy to see that ECONYL is able to answer the question #whomademyclothes and show me the faces of everyone who has helped to make the fibre for my new swimsuit #imadeyourclothes.

24 April is the most important day for fashion. But not because it’s Fashion Revolution Day. It’s because over 1000 men and women, with families, hopes and dreams just like us, lost their lives while making our clothes.

Did you know that 80% of our fashion is made by 18-24 year old young women around the world? Sadly the only time we hear about these millennial makers is when tragedies such as Rana Plaza occur.

When we ask more about them, we can change their lives. Let’s never forget Rana Plaza and keep asking our favourite brands #whomademyclothes?

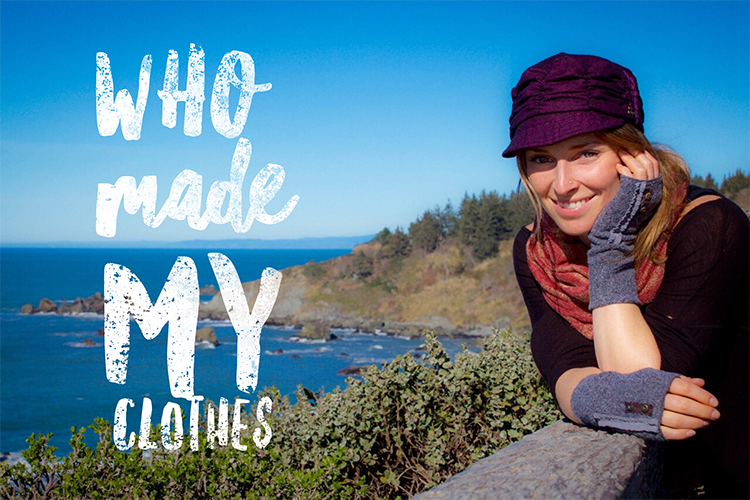

#whomademyclothes……..do you ever wonder? We are super excited that Fashion Revolution has opened the doors for people to explore this question and find answers. We are happy to share our story about the manufacturing of our Gypsy and Lolo accessories.

It all starts in North Carolina where our fabric is made from recycled cotton yarns. Here are Rodger and Jonathan working on one of the knitting machines.

Once the fabric is made it is shipped to our cutting factory in Oakland CA where it is cut by Daniel. Below is a photo of Daniel and his assistant rolling out fabric on the cutting table.

All the cuts travel from Daniels to our sewing factory in Alameda, Ca.

That’s about a 3 mile trip!

Angela and her sister Connie have owned and operated their small sewing shop in Alameda for 27 years. They employ 12 people all of which are paid and treated fairly. Both Angela and her sister Connie work alongside their employees, ensuring that they all have a good environment to work in. We often visit their factory with our 2 children and all of the workers greet them with smiles and treats.

Here is Angela working on a pair of our wrist warmers.

This is Chang sewing our scarves.

Karen doing the last inspections on our hats and getting them ready to ship to our warehouse in Arcata, Ca.

Now that all of our accessories are done being sewn they are ready to be packed and shipped off to stores across the USA. We do all the shipping from our warehouse in Northern CA. Here is Gypsy’s mom Nancy packing the boxes.

Thanks for caring and supporting brands that are ethical, eco friendly and transparent with their manufacturing process.

Sincerely, Loic (Lolo) and Gypsy

Carol is the Quality Control Supervisor at SOKO Kenya in the Rukinga Wildlife Sanctuary. She manages a team of 5 people, and her daily responsibility is to make sure that all of the factory’s production is up to standard. “I guess you could say I’m a perfectionist, “ says Carol, “at the factory I like to make sure everything is checked with great care and detail.”

Carol is from the Vihiga county in Western Kenya. After completing primary school she moved to Mombasa on the other side of the country in the hope of getting a high school education. Unfortunately her mother passed away a few months after she left. Carol’s grandmother looked after her siblings and cousins, but she could not afford the school fees. Carol found work as a cleaner for a local coastal family and sent money back to support her grandmother. In 2002 she met her husband and became pregnant with her first child. She was 16 years old. Without family around her to help to look after her baby, she was forced to quit her job while her husband supported the family with his income as a bajaj driver.

It was in 2009 that Carol’s prospect’s changed. She heard about SOKO Kenya and she applied for a job as a helper. Over the past six years, through hard work and an eagerness to learn, she has been promoted to a supervisor role. “Employment has not only empowered me but also it has motivated me in so many ways,” Carol says. “My dream is to become a designer.”

Last year Carol was awarded a scholarship to the UK, and she spent two months attending a pattern drafting and garment construction course. “I got to experience a life which is so different to what I am used to. I felt like the UK was a different world, and it made me wish that Kenya would one day be a developed country like that.”

“I attended other conferences, particularly about design, and it inspired me to start thinking out of the box. I found out that there are all different types of designers, even ones who design road signs! When I came back after two months I had so much knowledge to share with everyone, and endless stories to tell. My heart was filled with joy, my face full of smiles and a song of thanks to God for making this dream come true.”

The SOKO factory is based in an area which suffers from the lowest employment rates in Kenya. There are high rates of prostitution, HIV/AIDs and wildlife poaching. SOKO aims to empower women by providing employment and training in a safe and fair environment. Through this we hope to establish an ethical and sustainable workplace which will benefit the local people and the wildlife both now and for future generations.

80% of our fashion is made by women who are only 18 – 24 years old. Sadly we only hear about these women when terrible tragedies occur, be it the Rana Plaza disaster in Bangladesh in 2013, the horrific fire at Ali Enterprises in Pakistan in 2012, or Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in New York in 1913. The hopes and dreams of the women behind our fashion are eclipsed by heartbreaking headlines that hound the fast fashion industry.

Made in Pakistan is the story of two incredibly resilient women who make our clothes. They don’t want our pity. They want us to know them. We hope this short will move you to care about them and ask #whomademyclothes.

Rubina: I am 22 years old and wanted to be a doctor. Then my father got sick, so here I am, many years later, still at a factory stitching college sweatpants and hoodies that go to America. I don’t want you to feel sorry for me. I used to be shy and scared in the factory environment. But after all the injustices I’ve seen happen here, I’ve become a labor organizer. I go to management to demand that we are not harassed, paid on time, given proper food to eat. You would not believe the things I have seen. Stitching all day long my mind wanders and I think about you often. You having fun, wearing these hoodie on campus. I wonder if you think about me ever? The woman who made that for you. I am taking English classes at night. So that one day I can at least get an office job.

Lubna: After my husband left me and my infant daughter, I had to find ways to care for her and my aging parents. So here I am, many years later working at a garment factory. As I pull threads out of hoodies and do the final inspection, I sneak glances at the clock. My days are long and I miss my daughter so much. The other women on the line help me get through my days. We share secrets and the grief that is buried deep in our hearts. When the sun starts to set, its my favorite part of the day because I get to go home to my daughter. I don’t have very many dreams of my own anymore. I just hope for a better life for my daughter. I often imagine university students hanging out, wearing the hoodies that I helped make. I hope you know that my daughter and my life are woven into the threads of your hoodie.

Making of the film: Made in Pakistan is a part of Remake’s Meet the Maker series. We traveled and visited fabric mills, factories, dormitories and homes throughout the world in search of the women who make up fashion’s supply chain. So far we’ve been to Haiti, India, Pakistan and China, to sit down and eat meals, listen and learn about the triumphs and the heartaches of the women who make our clothes.

This film is personally very meaningful to me. I was born and raised in Karachi, Pakistan. I have for the last decade worked across brands, factory managers, government and unions leaders to invest in the lives of the people who made our clothes. We were fortunate to have partnered with an amazing Pakistani film crew. Our cinematographer Asad Faruqi and producer on the ground Haya Iqbal were thoughtful and persistent in capturing this story (and their recent documentary A Girl in a River has just won an Oscar!).

We hope you enjoy a glimpse into Lubna and Rubina’s life and think about them the next time you put on a hoodie or a pair of sweatpants.

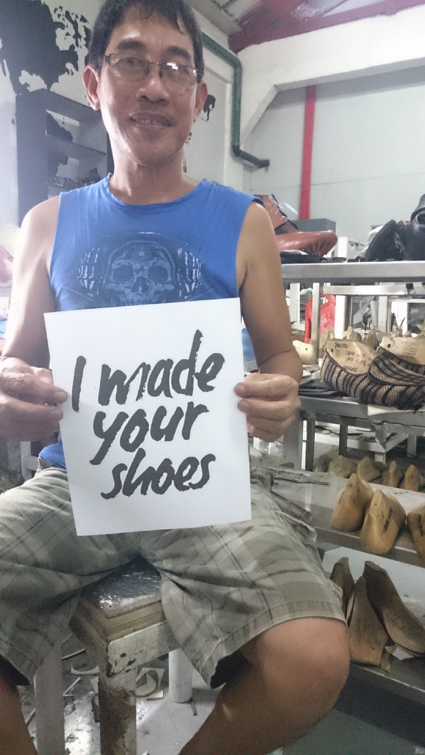

Fashion Revolution is here to connect makers and producers to consumers. In the Philippines, we have teamed up with Risqué Designs to demonstrate to the fashion industry that this is possible. Risqué Designs make fabulous made-to-order shoes from various local materials and supports weaving and artisan communities through sourcing everything locally.

Their shoemakers may also appear at their shop where shoppers can get detailed information on the products they made. Which is impressive! Not many brands do this! We encourage more companies to give their makers the opportunity to meet customers and connect with them. This is a great way to establish brand reputation.

Below are the stories of the shoemakers of Risqué Designs.

JOSEPHINE (NENETTE)

Role: Sample Maker

52 years old

When did you start making shoes?

In the year 2000 until present

Tells us how you progressed into the role you have now.

When I first started, I was stitching shoes, I was a seamstress for Puma. But as I observed my colleagues who had other roles I wanted to take on bigger tasks in the assembling process.

What are your hopes and dreams in the future?

I hope to have a shoe factory of my own and be able to designs shoes like Tal does.

How long have you been working with Risqué Designs?

Just over a year

What makes working with Risqué Designs unique from your previous work places?

I am able to help Tal in the decision process of choosing appropriate materials and Tal’s designs are uncommon and are different from mainstream shoes these days. It’s also nice to work in a place that has a friendly atmosphere, where we could be a family to each other and help each other develop skills and expertise. I am enjoying my work here!

What is the hardest part of your job?

When a design has intricate details

What is your favorite part of the job?

When I am making sandals and flat shoes

Rudolfo (Rudy)

Role: Pattern Maker

44 years old

When did you start making shoes?

When I was 14 years old until now.

How did you start?

I started stitching shoes in 1983 and connecting the soles to the body of the shoes by 1984. From 1996 until today, I do everything.

What is the hardest part of your job?

When there are complicated parts to assemble. You need a lot of patience!

Do you like working with Risqué Designs?

Yes, I like it here.

ROMY

50 years old

How did you start making shoes?

I started when I was 18 years old, like others I was also stitching parts of the shoes together.

What are your hopes and dreams for the future?

I want to be better in making shoes and to master the process.

What do you like doing in your job?

I like making men’s shoes and casual shoes.

If you are in Manila, Philippines and want to explore the city, why not drop by at Risqué Designs’ shop at the ground floor of Glorietta 3. The team is more than happy to meet you! Opening times are from 10am-9pm from Sundays to Thursdays and 10am-10am on Fridays-Saturdays.

The team of Fashion Revolution Macedonia visited the production premises of Di Biaggio NY in Kriva Palanka, Macedonia.

Maria is founder of sports brand Di Biaggio NY. She has lived in New York for years, where she worked as a Personal Trainer, but her interest in combining sport and fashion led her to set up a sportswear brand. She decided to set up the Di Biaggio production premises in her birthplace, Macedonia.

This brand has only been established for one year, but the team of seamstresses, pattern-makers and pattern cutters, who have been together for just three months, already share an amazing energy between them. Conditions are very good and the working environment is inspiring: the team is being paid fair wages, their working conditions are safe and most importantly, they are being treated very well. As we have seen the brand is respectful and kind not just to its employees, but also to the community in general.

Slagjana Stojkovska, Valentina Aleksovska, Vaska Ivanovska, Blaga Jovanovska and Lidija Ilievska are part of this team of valued and well-treated people, who made Di Biaggio NY sportswear.

Here are some photographs taken at their workplace.

Written by Ana Jakimovska, Country Coordinator for Fashion Revolution Macedonia

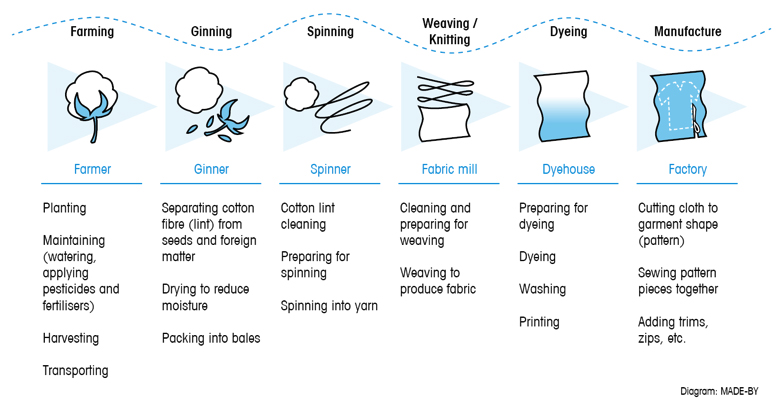

The fashion industry is incredibly complex.

Fashion is a global network. From growing the cotton, weaving it into fabric, dyeing and finally sewing the garment together, each step is completed by a different group of people, in different regions and even countries. Some brands have over 500,000 different products on the market at once worldwide, thousands of factories associated with them, and millions of workers all having a hand in creating their products.

It is positive that the fashion industry is able to support the employment of so many people, in regions where opportunities can be limited. The challenge, however, is making sure that the livelihoods of these workers are protected, sometimes even above the accepted standards in that country, and that the environments in which materials are extracted and processed are not negatively impacted by these activities. Many brands have invested significant resources to evaluate and decrease these impacts, however numerous continue to struggle with achieving transparency of their supply chain in the first instance.

Why is supply chain transparency a challenge?

The strength of fashion brands is in providing consumers with finished products they want to purchase – it is not in growing cotton, mining tin, dyeing wool, or all other stages of production of fashion. Because of this, their supply chains are setup to primarily place orders directly with factories which produce their final products. Some brands do purchase key fabric or components to their products, however brands are towards the end of incredibly intricate networks of factories and workers. To achieve transparency, brands need to work backwards to identify these factories who have had a hand in producing the components used to create their products.

We lead projects with brands to uncover their supply chains. These projects are always an ongoing process of communicating the intent to suppliers. The focus is on building trust in that brands are not seeking to leapfrog over suppliers to secure better commercial deals with upstream suppliers, but rather, honest attempts at uncovering who made their clothes and how these were made. We have had some great successes in these projects, finding ways to decrease impacts quickly, connect brands to workers who they would’ve never been able to tell stories about otherwise (e.g., Mongolian goat herders), and build comprehensive pictures of their supply chains and their associated risks. In some cases, we find deceptive behaviour or suppliers being unwilling to share this information. The brands we work with then need to make a decision. Some have decided to make a stand that it is no longer acceptable to them to source from suppliers who do not share this information. Others are still trying to get this supply chain shift sold internally. However, in both cases, the important thing is that transparency is now a factor in sourcing, and is being discussed by both sustainability teams and commercial teams as the new basis for further impact reductions. Without having visibility to these suppliers, brands are unable to support impact reductions more upstream in the supply chain. Once visibility is established, we have seen impact reductions of all sizes, from investing in new machinery to simply adding nozzles to hoses to save resources.

A fundamental shift is coming

By 2050, the global population is expected to reach nine billion people – all of which will not only need clothes. Climate change has already began impacting harvests for materials like cotton worldwide, and is only expected to cause further supply disruptions in the coming years. Industrial pollution too has devastated environments, with 43% of rivers in China being unsuitable for human contact (not consumption – contact). Competition for resource is ever increasing with poor yields from harvests, and even with resources we take for granted such as the groundwater level in Bangladesh dropping by multiple metres every year, requiring factories and communities to continue drilling deeper and deeper to find water.

Legislation and international guidelines are also changing worldwide which means that companies will have full responsibility for the social and environmental impacts of their supply chain from start to finish. For some brands, this will be a catalyst for action. For others who have already invested in projects to identify and support suppliers, their first mover advantage has put them in a better position to comply with these legislations, but also have created some other potential benefits. A key high-street brand recently shared that their commitment to sourcing Better Cotton Initiative cotton for their products created a space to build trust with suppliers, get to know them better, and support them with their challenges.

Transparency as an opportunity

We must be aware that opening up an entire global industry cannot happen overnight. Instead we should celebrate some of the leaders who continually engage with their supply chains, and share with the world some of their findings (both positive and negative) and some of their stories.

Transparency will be the vehicle by which brands can identify their supply chain, engage with these suppliers and improve the environmental and social impacts associated with the production of their products. Sustainability engagement has moved far beyond a charitable exercise, it is becoming a critical business activity.

Transparency is set to be a game changer on supply chains and effective action can begin to make this a reality.

Stefanie Maurice, Principal Consultant, MADE-BY

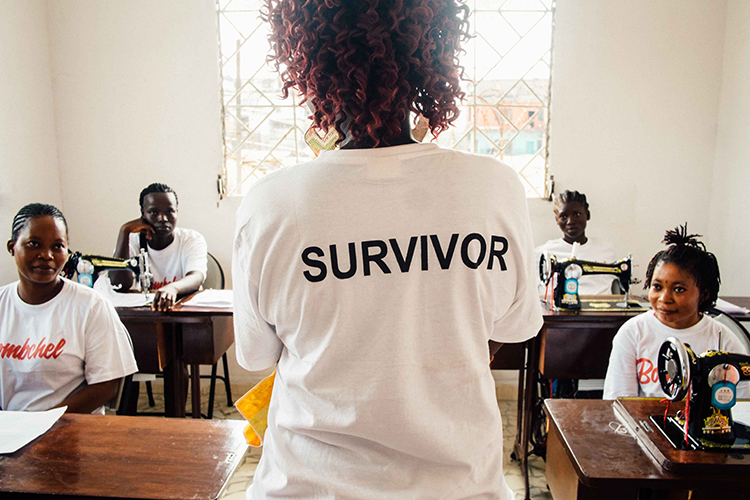

Meet Beatrice. At 27, Beatrice is a mother to a 14-year-old daughter, an Ebola widow, and she is learning to write the alphabet in her spare time. Now that she works at The Bombchel Factory, she is able to support herself and her family for the first time in her life.

Before she became a Bombchel, Beatrice sold fish in the market sometimes, but in her own words at our first meeting, ‘whole day I not doing nothing at home.’

The Bombchel Factory is an ethical African fashion wonderland based in the heart of Monrovia, Liberia that trains disadvantaged women like Beatrice how to sew contemporary garments for sale.

When I started The Bombchel Factory, I just needed a place where women would make clothes for sale in my store, Mango Rags, or for the occasional US festival. I knew I wanted to help women as much as I could, being that I am a proud woman and most of the tailors in Liberia are men. In a country where most of the women are uneducated and unskilled workers, I couldn’t have imagined that we would get to teach women how to one day write their name, like Beatrice. I didn’t expect we would find a team mama, Sis Emma, who keeps the women in line but also builds their confidence. I didn’t think we would have a future Baby Bombchel on the way from our expecting manager, T Girl. I definitely didn’t expect that we could raise $60,000 on a crowdfunding campaign all the way in little Liberia!

Through The Bombchel Factory, I learned that fashion can do more than just transform the way a woman looks, but it can revolutionize the way she lives. The most exciting things I’ve learned from our wonderland have to do with the people who have helped to build it.

In a country that has seen civil unrest, Ebola, and everything in between, we’re excited to be ethically stitching together a silver lining for Liberia.

by Archel Bernard

H&M ha declarado la “Semana Mundial del Reciclaje” del 18 al 24 de abril de 2016 con una campaña de marketing de gran envergadura que pretende recoger 1.000 toneladas de ropa usada durante esa semana y reciclarlas para convertirlas en nuevas fibras. Fashion Revolution desafió este objetivo, señalando que sólo una pequeña fracción de las 1.000 toneladas propuestas como objetivo pueden convertirse en nuevas fibras textiles ya que la tegnología para ello aún no existe. La organización también desafió lo desconsiderado del momento para la promoción, que coincide con el 24 de abril, justo cuando hace tres años 1.134 personas murieron en Rana Plaza, en Bangladesh, haciendo ropa para cadenas minoristas, y H&M es el mayor productor de prendas en Bangladesh.

Orsola de Castro, co-fundadora de Fashion Revolution ha dicho: “Esta semana, de todas las semanas, H&M debería trabajar en solidaridad con el resto de nosotros para marcar el aniversario de la tragedia de Rana Plaza. Debería ser un momento para todos nosotros para honrar a los trabajadores textiles, aquellos que han muerto en tragedias industriales de la industria textil y aquellos que todavía hoy sufren en la cadena de suministro textil. ”

Fashion Revolution también señalaba el lenguaje confuso usado para describir el impacto de la iniciativa de reciclaje de H&M. Estábamos emocionados de que tanta gente mostrara su apoyo por una mayor transparencia y ayudara a comenzar una conversación sobre temas controvertidos relacionados con la exportación de ropa de segunda mano a países en desarrollo.

“Estamos contentos de que H&M haya admitido las verdaderas cifras de lo que se revende, lo que se reusa y lo que se convierte en nuevas fibras y de que cambiara el objetivo en su web en consecuencia. Esto ha sido algo muy influyente de hecho – usamos nuestra voz colectiva de manera moderada y hicimos que una de las mayores corporaciones del mundo diera un paso hacia una mayor transparencia.

Esperamos que H&M elimine su cupón de descuento en el futuro para no alentar un mayor consumismo entre sus jóvenes consumidores – eso sería el próximo paso lógico al abordar correctamente el tema de los residuos textiles. ”

H&M respondió con el siguiente comunicado: “Tan pronto como Fashion Revolution nos hizo conscientes de sus preocupaciones, comunicamos claramente qe no tenemos la intención de convertir en esta semana en particular como una Semana Mundial del Reciclaje de manera recurrente en el futuro, y hemos ofrecido inmediatamente elegir otra semana si hiciéramos otra Semana Mundial del Reciclaje en el próximo año o siguientes. ”

Fashion Revolution Week tiene lugar del 18 al 24 de abril en 89 países en todo el mundo. Por favor únete y ayuda a aclamar a los verdaderos héroes. Visita www.fashionrevolution.org para encontrar un evento cerca de ti. Juntos podemos hacer que el cambio ocurra.

Por favor ¡apoya a Fashion Revolution para ayudarnos a hacer nuestro mensaje más fuerte! Cada donación nos ayudará a dar voz a todos los implicados en la cadena de producción. Gracias por ser parte de este movimiento y por ayudarnos a seguir siendo fuertes.

Nota para prensa

- Millones de personas saldrán a la calle durante la Fashion Revolution Week para despertar conciencias y hacer preguntas sobre las condiciones a las que se enfrentan los trabajadores textiles y la persistente falta de derechos humanos en la industria de la moda, y para homenajear a la gente que está detrás de lo que llevamos – desde el granjero a la hilandera, la tintorera, sastres y más.

- Durante la semana del 18 al 24 de abril de 2016, te animamos a que pienses lo que hay en tu armario. Si tienes prendas sin estrenar, ¿podrías hacer algo con ellas en vez de deshacerte de ellas (en H&M o en cualquier otro lugar)? Lo podrías intercambiar con un amigo que lo aprecie más, o tal vez lo podrías modificar para que lo puedas seguir amando más tiempo. O por qué no probar nuestra Haulternative, y descubrir 8 maneras de renovar tu armario sin comprar nuevas prendas.

- Fashion Revolution Week se celebra del 18 al 24 de abril de 2016, no te olvides de preguntarle a tu marca favoria #quienhizomiropa o #whomademyclothes.

On April 24th, 2013, 1,134 garment workers died when an eight-story building, named Rana Plaza, collapsed in Dhaka, Bangladesh. This event marked the beginning of Fashion Revolution Week (April 18-24). It is a time for us to honor garment workers, those who have died in all industrial tragedies in the garment industry, and those who are still suffering in the fashion supply chain today.

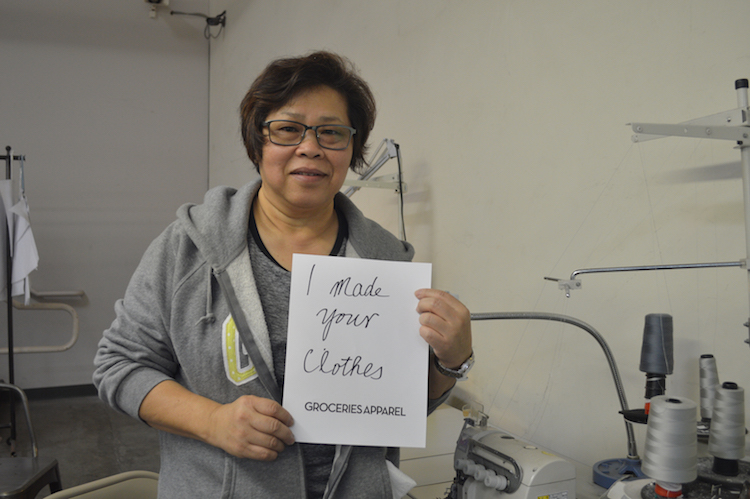

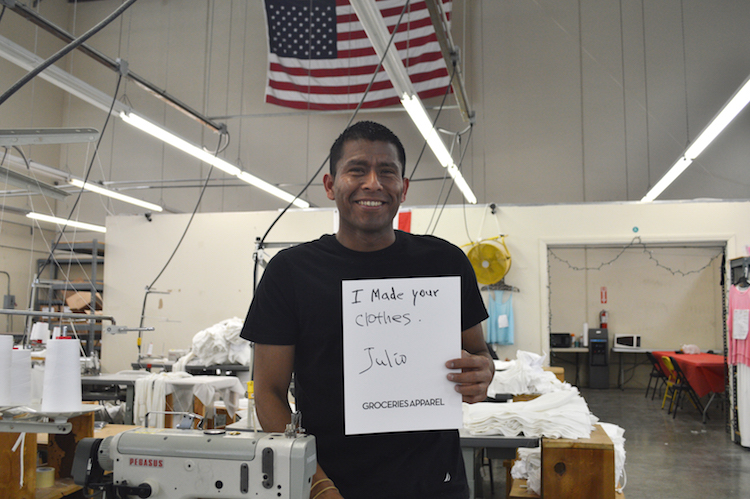

At Belvele, we are taking this opportunity to highlight fashion brands who are doing the right thing, by paying fair wages, providing safe working conditions, and treating their talented employees with the respect that they deserve. Although all of our vendors produce ethically, Groceries Apparel and Threads 4 Thought were nice enough to introduce us to some of the people who are making your clothes.

Groceries Apparel

Groceries Apparel operates its own factory in Los Angeles, taking responsibility for their impact on customers, employees, communities and the environment. In addition to ensuring ethical manufacturing, the company uses environmentally conscious materials, such as organic cotton and recycled polyester.

Linda is the pattern maker and a co-founding member of Groceries Apparel, who has been with them for over six years.

Julio is the sew team manager. He has been working at Groceries Apparel for five years.

Threads 4 Thought

Eric and Leigh, the company’s founders, personally travel around the world to find the best Fair-Trade facilities that share their values, and to build relationships with the owners, management, and workers. Their locations include Kenya, India, China, and Haiti. All garments are made with sustainable textiles, such as Organic Cotton, Lenzing Modal, and Recycled Polyester.

Jael works at Wildlife Works in Kenya, one of Threads 4 Thought’s Fair Trade Certified partners, which is located inside an 80K acre wildlife preserve.

Dorothy produces graphic tees and tanks for Threads 4 Thought at Wildlife Works, a carbon-neutral factory which is part of the REDD+ Project, which protects forests, wildlife, and communities in Kenya.

As Fashion Revolution Week approaches, we encourage you to find events near you, and to get involved with the slow fashion movement. Ask your favorite brands on social media, #whomademyclothes to encourage them to be transparent and let them know that you care about their supply chain. With each dollar we spend, we place a vote for the kind of world we want to live in.

Join us on 4/21 for a screening of The True Cost.

If there’s one item of clothing that deserves to be branded “wearable art,” it’s these exquisitely carved heels which Mr Van Do Thanh makes for Saigon Socialite.

Melding French leatherwork with the ancient Vietnamese art of pagoda carving, the shoes are the brainchild of Lan Vy Nguyen, the Vietnam-born, California-raised founder of Fashion4Freedom. Lan Vy founded the social enterprise with the goal of alleviating poverty through ethical manufacturing and the preservation of ancestral craftsmanship. Despite their modern context, the so-called “reincarnated soles” abide by cultural mores.

Fashion 4 Freedom puts work of Vietnamese artisans into the light. This is a beautiful way to maintain traditional skills and cultural heritage by showing us the people #whomademyclothes.

Post by Florence Bacin.