Sheepskins and Knitting Yarn in the Outer Hebrides, Scotland.

The shipping forecast issued by the Met office at 11:30 UTC on Friday 27 January 2017. Northwest Hebrides, Bailey – Southeasterly 6 to gale 8, becoming cyclonic gale 8 to storm 10 then southwesterly 5 to 7 later. Very rough or high, becoming rough or very rough later. Rain then showers. Moderate or poor, becoming good.

January and February are always the toughest months in the Hebridean islands off the north-west of Scotland. For both humans and animals our resources and resilience are at their lowest point, the days are short and dark, the weather extreme and wild.

However, amongst all this there is still beauty and special moments of fiery sunrises, otter tracks to the shore and soaring golden eagles.

In 2015, I tentatively started The Birlinn Yarn Company from our family croft (small holding) at Sunhill on the small Hedridean island of Berneray in the Sound of Harris. We have lived here for the past twenty years, worked, renovated two properties and brought up two sons. We now produce deep luxurious sheepskins and a range of knitting yarn from our own fleeces and those we buy from neighbouring crofters.

Hebridean sheep, dark fleeced and horned, were originally brought here by the Vikings in their long boats around 800 A.D. Overtime the long boats, built for long distance sea voyages were adapted for inter-island travel and became the Hebridean galley or Birlinn. Hence the brand name Birlinn Yarn, what’s more they are still ‘seafaring sheep’ as we take them to and fro from the islands by boat.

Supporting and maintaining traditional crofting (small scale agricultural) practice, which has maintained equilibrium and respect for the ecology for hundreds of years, is very import to our business ethos. We use seaweed to fertilise our crops, keep stock to low intensive levels and every activity or action is measured against the impact to the environment.

Our agricultural activities are set mainly by the rhythms of the weather and seasons. Our sheep lamb on the croft, then once the lambs are strong enough we take them all to the islands for summer grazing. Here they graze on a wide variety of plants, including seaweed, a bit like trying to attain our 5/day fruit and veg – resulting in a good healthy diet.

In July, we return to shear all the sheep on the islands. We choose a good forecast, wait for a crowd of cousins to come up on holiday to help out and it always turns out to be a long, hard but very enjoyable day.

In the autumn the ewes are brought back to the croft to meet their boyfriend (the tup) and then they spend the winter months grazing on the machair (raised beach) to the West of the island. And so the cycle continues …

Amongst many other activities, I am also a practicing visual artist http://www.megrodger.com with an exhibition currently showing at Taigh Chearsbhagh Museum & Art Gallery in Lochmaddy, North Uist. While my current fascination is working with the wind to generate drawings, I am always taking note of the wonderful range of colours we have in the Hebrides.

Thus, just this week, I have launched a new organically dyed knitting yarn range reflecting the subtle tones and shades of the Hebrides. Our ecosystems here are as much Highland as Island given that our habitats range from moor, to machair, shore and sea. In relatively short distances, you can encounter gliding golden eagles, wild orchids, playful otters and roaring Atlantic breakers on the shore.

This range of organic dyed yarns have been produced as a unique and small batch to complement out natural yarns. By over-dying a blended yarn this has given the colours both texture and depth. The yarns come in four colours: Sgeir – Reef, Còinneach – Moss, Monadh – Moor and Duileasg.

What next? Well, I hope this year to work with a knitwear designer who understands our ethos and brand to develop knitting patterns incorporating both the Norse and Hebridean heritage of our sheep and islands.

In the meantime, why not take a look at our website, be tempted and knit yourself a wee bit of the Scottish Hebrides.

http://www.birlinnyarn.co.uk

https://twitter.com/BirlinnYarn

https://www.facebook.com/BirlinnYarn/

Oxford Dictionaries declared post-truth to be the international word of the year for 2016. The word was chosen to reflect the politics of the past twelve months. Truth has been relegated to a bit part on a stage where politicians appeal to emotions and feelings, rather than thoughts and minds.

Fashion Revolution is a pro-truth campaign.

A poem by Sasha Haines-Stiles in Fashion Revolution’s new zine Money Fashion Power concludes:

Who embroiders truth

Who’s naked underneath

Who are you

Who are you wearing?

Illustration by Alec Doherty

For Fashion Revolution, truth means transparency and transparency implies honesty, openness, communication and accountability. Transparency means that if human rights or environmental abuses are discovered, it is far easier for relevant stakeholders to understand what went wrong, who is responsible and how to fix it. It also helps unions, communities and garment workers themselves to more swiftly alert brands to human rights and environmental concerns.

In order to create a sustainable fashion industry for the future, brands, and retailers must start to take responsibility for the people and communities on which their business depends. The factories operating in the Rana Plaza complex made clothes for over a dozen well-known international clothing brands, but it took weeks for some companies to determine whether they had contracts with those factories, despite their clothing labels being found in the rubble. Lack of transparency costs lives. It is impossible for companies to make sure human rights are respected and that environmental practices are sound without knowing where their products are made, who is making them and under what conditions. If you can’t see it, you don’t know it’s going on and you can’t fix it. Tragedies like Rana Plaza are preventable, but they will continue to happen until every stakeholder in the fashion supply chain is responsible and accountable for their actions and impacts.

This week sees the inauguration of new US President Donald J Trump. The Washington Post called him ‘the least transparent U.S. presidential candidate in modern history’ due to his failure to release his tax returns or provide evidence for the tens of millions of dollars he has reportedly donated to charity.

At Fashion Revolution, we are working on compiling the next edition of the Fashion Transparency Index which will cover 100 of the major global fashion brands with a turnover above $1.2 billion. Ivanka Trump’s brand does not disclose her financials, but we thought it would be interesting to measure her transparency against the criteria we used for the 2016 index to see how she would score. Last year we rated and ranked 40 companies based on how transparent they are. Those who are more transparent get more marks than those who are less transparent. It uses a ratings methodology, which benchmarks companies against current and basic best practice in supply chain transparency in five key areas:

The lowest percentage scores in our 2016 index, were achieved by Chanel who scored just 10%, and Hermès and Claire’s Accessories who each scored 17%.

Measured against the same criteria, Ivanka Trump’s brand would have scored 0%. Her website discloses no information at all. Nothing.

Fashion Revolution’s mantra is Be Curious, Find Out, Do Something. We ask people to dig deeper, look for evidence, hold brands to account, ask them #whomademyclothes. The New York Times has carried out research into Ivanka Trump’s supply chain. According to a review of shipments compiled by import databases Panjiva and Import Genius, the latter of which tallied 193 shipments for the brand during 2016, her shoes and handbags are made principally in China, whilst her dresses and blouses are made in China, Indonesia and Vietnam.

Ivanka Trump’s website is post-truth. It’s not untruthful, but it appeals to the emotions of consumers to sell her clothing, rather than providing any facts. It claims to be the ultimate destination for Women Who Work, but what about the women who work for her in China, Indonesia and Vietnam? Her website contains no code of ethics, no supplier or vendor code of conduct, no sustainability or CSR report, no manufacturing list, no human rights or environmental policies. Nothing.

In the past month, critics of Donald Trump have taken to posting ironic reviews of Ivanka Trump’s Issa boots on Amazon.

On 13 December Lucinda Tinsman posted

Very narrow boots; go well with people with a narrow-minded outlook on life and actively the validity of people of diverse backgrounds from being worthy of civil rights. Because they are made of man-made materials, very difficult to breathe in. Due to the escalation of climate change they are linked to, in all likelihood the wearer will not be able to breathe at all within one generation. They are the product of pure greed, which doesn’t make any sense because even the wealthiest individuals’ children and children will die if their father’s and father’s father’s actions led to a world that cannot support human life, which is what is happening as we speak. Do not buy, for the good of the country or for the good of your children.

Susan Harper gave the boots a five star rating, explaining

The leather is perfectly conditioned with the sweat and tears of underpaid sweatshop workers, and will keep its beautiful sheen for years.

Without being truthful and transparent about how and where her clothes are made, Ivanka Trump can do little to refute disparaging comments about her supply chain. Yes, the reviews are ironic, but if Ivanka Trump had been more honest from the outset, she could perhaps have avoided significant reputational damage to her brand.

The Globescan Corporate Responsibility Radar 2016 found that transparency is a critical driver of trust in business; being seen as open and honest is the most significant driver of trust, yet consumers across the world rate the performance of companies poorly for “being open and honest.” Brands not only need to know their supply chain in detail, but this information also needs to be made available to the consumer in a way which informs and educates and starts to rebuild public trust in the fashion industry. Brands who practice transparency can help build customer trust and enhance their reputation at the same time as safeguarding the health and wellbeing of their workers and the environment.

As George Orwell said in 1984 ‘In a time of universal deceit, telling the truth is a revolutionary act’. So let’s see a revolution and let’s make transparency the word of the year for 2017.

On 24th April 2017, the anniversary of the Rana Plaza collapse, the second edition of our Fashion Transparency Index will be published. It will review and rank 100 of the biggest global fashion and apparel brands and retailers according to their level of supply chain transparency. Brands have been chosen on the basis of two factors: 1) voluntarily requested to be included; and 2) according to annual turnover, over $1.2 billion USD and representing a variety of sectors including high street, luxury, sportswear, accessories, footwear and denim from across Europe, North America, South America and Asia.

By Allison Griffin for Remake

Few things are more powerful than a room full of women who have something to say.

As part of our Remake Journey we traveled 2 hours outside of Phnom Penh along dirt roads to a small school in the middle of rice fields, one of the few safe places makers are able to unite to talk about their rights without the police breaking up the meeting.

This gathering was hosted by Solidarity Center, to help makers fight for their rights. We learned that when big factories agree to cheap prices and tight deadlines, they often can’t meet these demands. So they ship orders off to fly by night operations–dark, dingy subcontracted factories where the conditions are the worst.

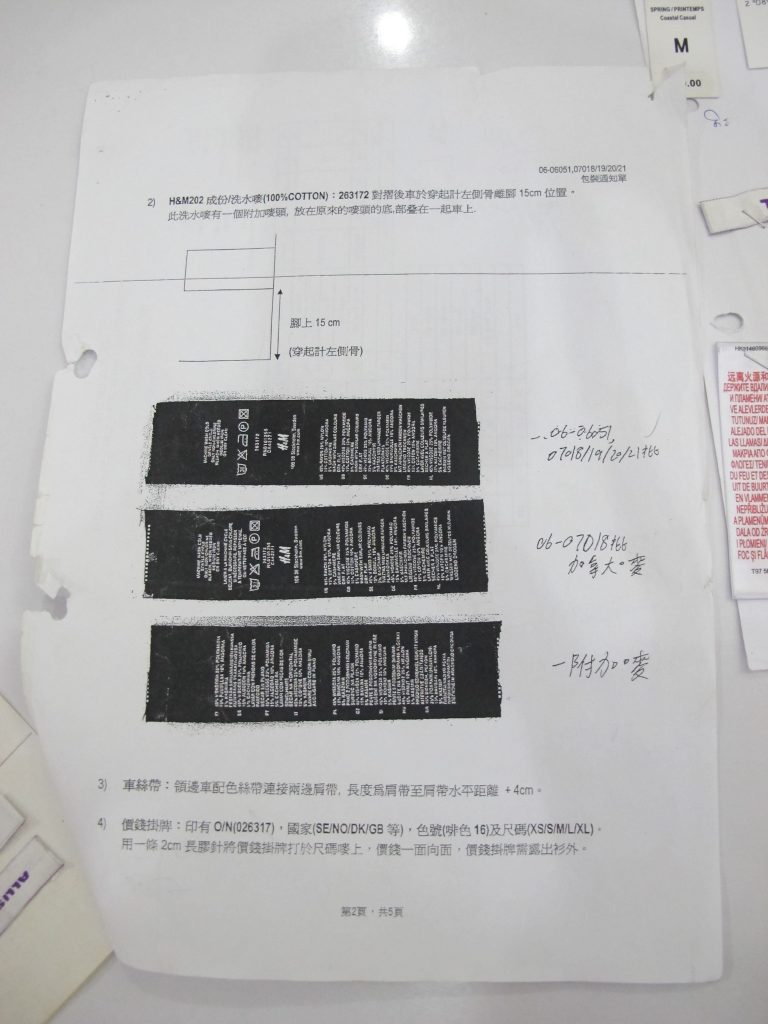

The women we met had sneaked out labels from the brands they illegally sew for including Zara, H&M and Tommy Hilfiger. It was dangerous for them to sneak these photos and labels out but they did it anyway, in the hope that we and you as readers would help them, to ask these brands pressing questions about why they worked such long hours for so little.

I had the honor of sitting down with one such maker, Char Wong. This is her story:

I grew up in a family of eight children raised by a single mother. I was a farmer before working in a subcontracted garment factory. I found work in a subcontracting factory to earn more money and provide a better life for my own family, but the pressure from the daily quotas is stressful and the money is not enough.

I support my 16-year-old son, 10-year-old daughter, my elderly mother, along with my husband who is a farmer. I struggle to feed everyone with the minimum wage and extra $2.50 a day that I earn. My mother has diabetes and her medicine costs $30 a month, over 20 percent of my monthly income. I also want to save money for my children’s education.

wanted a better life for myself and my family which is why I took this work. But life has become harder. I get paid per 12 pieces, but if there’s even one single error in the batch, I don’t get paid at all.

A few years ago, the factory would receive an order for a new design every two or three months, but with the new fast fashion cycles, it now gets more and more new designs in a shorter amount of time. Learning complex designs is very difficult and we get no training. Sometimes it takes two or three hours just to learn and the factory supervisor scolds us for any mistakes. The more time it takes to learn a design, the less time I have to meet the quota and the less money I make. I typically make $5 a day, but with the more complex designs, I only make $2 a day.

Sometimes I cry because I fear I won’t meet the quota and get paid.

Like most parents from all corners of the world, I want a better future for my two children. I hope to pay for their college education so that they can work in Cambodia’s government. Government jobs pay well and do not require hard physical labor. I hope that my children can be government leaders and help improve the conditions and rights of future garment factory makers, just like myself.

I am grateful for organizations like the Solidarity Center, who teach us about our rights. I am learning to speak up more. I want my story and my colleagues’ stories to spread to people throughout the world.

You being here, listening, makes me hopeful.

I definitely felt a lot of girl power throughout the day, both from our own all female crew and the makers we met. These women are not playing victims, but fighting for their rights and educating themselves on their rights. Speaking with Char Wong, I realized that the hopes she has are fundamentally no different from mine–for a fulfilling life. I hope as a designer, I can be a part of the change and that this story moves you to buy better. Together we can #remakeourworld.

From the very beginning, our artisans have always been our partners in positive change and empowerment! The journey of R2R, after all, really started with them. It was through their amazing talent of weaving and this artistry’s capacity to transform lives for the better that R2R became what it is today.

We’re pretty sure you’ve met some of our artisans in our Weaving with the Weavers events or even in our stores –– yes, some of our store ambassadors are artisans, too! But we have a wonderful (but very elusive!) group of artisans we’d love to introduce to you. You don’t get to see them often because these are our workshop artisans! They’re the ones running our humble workshop, assembling your bags to perfection before they land in our stores.

In honor of Fashion Revolution Week, we’re going to take you through our workshop and introduce to you the faces behind our production process!

1. NHING ESTABILLO, WORKSHOP SUPERVISOR

Ate Nhing started as an urban artisan from our Payatas community back in 2008 and since 2012, she’s been in charge of our workshop’s overall production, monitoring targets and making sure her team of amazing artisans create high quality bags and home items for you, our dearest advocates.

Update: Ate Nhing is now our Sales Ambassador! You can meet her in our Trinoma or UP Town Center stores!

2. BERNABE “BING” LOR, TEAM LEADER OF CUTTING

Kuya Bing, as we call him, is the lead of our workshop’s cutting team. Cutting is the very first step in our workshop’s production process! He and his team lays out the foundation of the bags by cutting and preparing the raw materials needed to make R2R bags. Once they’re done, the materials then get passed onto the other steps of our production process!

3. RUFINO “JUN” GAYANILO, JR., TEAM LEADER OF ASSEMBLY

Kuya Jun leads our workshop assembly. Once all the raw materials –– from the handwoven fabric to the bags’ hardware –– have been prepared, he and his team take all these different parts and put them together to build the R2R bags that you own and use today.

4. JIMBO ZIPAGAN, TEAM LEADER OF SEWING

Kuya Jimbo is our workshop’s sewing team leader! He’s in charge of the major and minor sewing of all our bags and home items. Even with that big of a responsibility, he’s one of the people in the workshop who’s always wearing such a huge and happy smile! It’s SUPER contagious, we swear!

5. FLORENCIA “FENCIA” FONTE, TEAM LEADER OF QUALITY CHECKING

Ate Fencia leads the workshop’s quality checking team or QC, as we call it! They’re the ones making sure that each and every bag is up to par with our standards of excellence. We don’t just QC the pieces after it’s done; we also check per stage so we see if each part of the bags were prepared properly, from the handwoven fabric to the cut leather. It’s a very important step of our production process because we always want to deliver high quality pieces to you, our advocates.

In R2R, we believe that fashion can be made in a safe, clean, and beautiful way and where creativity, quality, environment, and people are valued equally. That’s why we think it’s super important to ask the questions: #whomademyclothes, #whomademybags? Join the Fashion Revolution!

Header photo: Carry Somers, co-founder of Fashion Revolution, visits the Rags2Riches workshop in October 2016.

By Allison Griffin for Remake

I am not nervous to speak with you at all. My life has been full of hardships. At this point I am not scared of anything.

We met Sreyneang, a woman who has been working inside a Cambodian denim factory for three years, but has worked in the garment industry for many years. We traveled back to her home with her after her shift in a vehicle similar to a tuk tuk, but larger and less put together. The motorbike pulled a wagon with wooden beams across as seats and you had to balance the weight of people sitting, so that it would not tip over.This or trucks with empty backs are what most of the makers in Cambodia take to and from the factory.

I’ve been sewing since I was 15, my whole life. My husband was a security guard but he got sick. So now my garment maker salary supports him and my two daughters.

I work two jobs. I get up early. Take my kids to school. Then I take transport to the factory. At night I work as a tailor to supplement my income. I usually work until 10 or 11PM at night.

My home village is 3 hours away but I have a small house I bought here, which is unusual because most of my colleagues in the factory are stuck renting from landlords who raise the rent every time our wages are raised.

Her home was at the end of a dirt road and there were a lot of children all around. It was one room with earth flooring and a woven mat and benches, but no beds or indoor plumbing, but it did have electricity. She said she saved up to buy this land and built this house because it was closer to work.

My daughter told me she would drop out of school and start working to help me because she knows how stressed I am. But I said NO. She’s 14. I want her to stay in school and have a different life than me. I want my daughter to go to a school like Parsons and become a designer!

At dinner, she bought water bottles for all of us, which was very kind because they are expensive. While eating dinner, Sreyneang said she usually has only two spoonfuls of rice for dinner. It definitely put things into perspective and you could see the direct effects of low wages.

Sreyneang said she felt blessed that she met us. She wondered if her life would change from this meeting. We parted ways with WhatsApp numbers, big hugs and promises for a future evening together.

The world is round and we are all sisters. I want designers to know of the hardships and suffering in my life, of makers’ lives and the low wages we get.

Fashion design schools have an allure. Many young women in their early twenties get fashion degrees hoping to launch their own lines and drive the aesthetic of a camera-ready $3 trillion industry.

In reality, they enter a competitive market, applying for entry-level design positions in expensive cities. If accepted, they will work long days, under tight deadlines and fluorescent lights, all for salaries as low as $30,000. These graduating designers have little choice but to dive in and hope for a better future.

Interestingly enough, overseas, where roughly 97% of our clothes are made today, there are also young women in their early twenties toiling away on the assembly line. Their wages are low, working hours long, and conditions often difficult. And yet, for these young makers, factory jobs also represent hope for a better future.

Today we buy more clothes and yet somehow pay less for them. This phenomena called fast fashion, much like fast food means the industry cuts corners. What started as a way for more of us to look good on a budget has resulted in a rise in cheap, chemical filled clothes, brought to us by human hands forced to work longer hours for low wages.

But this article isn’t about shaming the fashion industry for building a broken business model. It’s about linking the amazing women on either end of the supply chain – designer and maker – to come face to face, woman to woman, to create a more human centered fashion industry.

80% of the people who are making our clothes are women, usually just 18-24 years old. Their hopes and dreams match ours: to be happy, healthy and see the world. At Remake, we pass the mic back to the women hidden at the other end of the supply chain. We have traveled to Haiti, India, Pakistan and China, to ask her to share her stories.

Our recent Remake Journey to Cambodia was in partnership with Levi Strauss Foundation and Parsons School of Fashion, home to fashion icons such as Donna Karan, Alexander Wang and Tom Ford. We took three of Parsons’ amazing graduating designers:

“As a fashion designer, we are so distant. A lot of our industry uses makers oversees and are so disconnected from them, but these are the people who are creating our work and our designs. So meeting with them and having that more manifested in our heads is a connection we need to be thinking about more.”

Meet Allie Griffin, whose great grandmother used to make our clothes right in NYC’s old garment district. Coming to a prestigious school like Parsons and recently interning at Oscar de la Renta, she feels that in one generation her family has come full circle from maker to designer.

“Fashion effects economies, politics…something you don’t normally think about. But at the end of the day there are people making our clothes, human lives depend on these jobs. That’s why fashion is important to me.”

Meet Anh Le, who designs menswear and has recently interned at American label Thom Browne. Her parents came as refugees from Vietnam, where her family worked in the garment industry. As an Asian aspiring designer, she wants to do right by creating clothes that are ethical and respect the maker.

“I’m really interested in being part of this new generation of fashion designers. We are interested in finding ethical and sustainable ways to participate in fashion. There are a lot of problems that I see, like low wages, underage workers, poor working conditions. I know a lot of my fellow students and I think it’s time to change how we make fashion.”

Meet Casey, who has designed future forward collections in collaboration with Tide and Intel. She is deeply interested in creating more sustainable patterns and textiles in union with factory systems.

Day 1: Tonlé: Zero-Waste Fashion

We visited Cambodia’s first zero-waste brand Tonlé to experience the power of fashion as a force for good. Tonlé provides at-risk women with a living wage, health care and good working hours, while also being good for our planet.

“From the moment we stepped inside the gate you could feel it, it was such a special place. There were a group of women at tables in the front yard knitting together, and they welcomed us warmly with smiles,” recounted Casey. “I spoke with Ny, a transgender male who is in charge of stock and shipping.”

“I think about how the clothes we make go all over the world. I also think that the people who buy from Tonlé really care about us, the people who make them. Most of the makers in the clothing industry come from really poor places, and they work so hard to try to achieve better lives. I want there are more brands like ours so that there are more people who have jobs as good as mine.” – Ny

Day 2: 2,000 People Making Our Jeans

We traveled down a winding bumpy and dusty road to a denim factory on the outskirts of Phnom Penh where jeans are made for every imaginable brand: from JCPenney and Kohl’s to Simply Vera by Vera Wang and J Lo.

Walking down the assembly line, you see hundreds upon hundreds of women, heads down doing fast repetitive motions, backs crunched just like ours over laptops. The sheer volume of stuff, and noise from the machines was overwhelming. All in our quest for cheap jeans.

The denim distressing unit was especially eye-opening.

“All the cuts, wear marks and washes are done by human hands, and these tasks are clearly physically demanding and even dangerous, from all the spraying of harsh chemicals. As soon as our tour ended my brain was overwhelmed with what I had just seen; how could one pair of jeans sell for $20 and have had so many hands work to produce them; the math behind where the money goes does not scream fair at all.” – Casey

That evening one of the denim makers invited us to her home for dinner in a nearby slum. We traveled in the open air truck with her, where passengers need to balance sitting on both ends to ensure the truck did not topple over. Makers in Cambodia have lost their lives in trucks just like this one, which thousands use to get to work everyday.

“I started working when I was 15. Since then I’ve worked at several different factories. My husband is sick, so my $140 a month salary support’s my whole family. I work at the factory all day and then work a second job as a tailor at night. I want my daughters to learn English and go to a school like Parsons. I’ve actually seen New York on TV and maybe someday I can come visit. I want young designers to know about my life. I have suffered but I feel stronger having met my sisters from NYC.” – Sreyneang

Sreyneang’s home was no bigger than two dining tables pulled together, the floor just dirt and the roof sheet metal. Her husband, children and neighbors all crowded in to meet us. Her home may have been small but her heart was huge. When we sat down to eat together, she kept offering us bottled water she had bought for us and took only two spoonfuls of rice. Insisting that we, her neighbors and even the stray dog and cat that stopped by had something to eat first.

“A truly inspiring, loving, and kind soul, I haven’t stopped thinking about her and I don’t think I ever will.” – Casey

Day 3: Sub-Contracted Factories, The Most Invisible People

Few things are more powerful than a room full of women who have something to say. We traveled 2 hours outside of Phnom Penh along dirt roads to a small school in the middle of rice fields, one of the few safe places makers are able to unite to talk about their rights without the police breaking up the meeting.

This gathering was hosted by Solidarity Center, to help makers fight for their rights. We learned that when big factories agree to cheap prices and tight deadlines, they often can’t meet these demands. So they ship orders off to fly by night operations–dark, dingy subcontracted factories where the conditions are the worst.

The women we met had sneaked out labels from the brands they illegally sew for including Zara, H&M and Tommy Hilfiger. It was dangerous for them to sneak these photos and labels out but they did it anyway, in the hope that we and you as readers would help them, to ask these brands pressing questions about why they worked such long hours for so little.

Some of these women made less than a $100 a month despite working all day long. Others noted that they were forced to take pregnancy tests and if it was positive, they were fired.

We learned that some factories pop-up during holiday rushes, then shut down to avoid paying the makers anything once the order is filled. Some of these women had been sleeping outside factories to get their back wages to afford food and rent. One of Solidarity Center’s incredible staff leaders Somalay, said to us,

“We will never stop. We will fight.”

She cares and risks her life, because she’s been there, she used to be a garment maker herself.

“I wanted a better life for myself and my family so I took this work at a subcontracted factory. But life has become harder. I get paid per 12 pieces, but if there’s even one single error in the batch, I don’t get paid at all. I used to make a new design every 2-3 months. Now, it’s two to three new designs per month. The designs are more complicated but we get no training. It’s harder to meet the quota. Sometimes I cry because I fear I won’t meet the quota and get paid. I hope you will help me and my colleagues by spreading our stories to the world. You being here, listening, makes me hopeful.” – Wong Char

“I definitely felt a lot of girl power throughout the day, both from our own all female crew and the makers we met. These women are not playing victims, but fighting for their rights and educating themselves on their rights. Some of the makers dressed up in professional attire, including blazers and heels and every person had a pen and paper they were furiously taking notes with. Speaking with Wong Char, I realized that the hopes she has are fundamentally no different from mine–for a fulfilling life.” – Allie

Journey #5 ended with see-you-laters, not goodbyes. Our designers and makers became friends on Facebook WhatsApp and promised as sisters to keep in touch and fight together to make fashion a force for good.

It takes 100 pairs of hands to bring each of our clothes to life. Next time you go shopping, we hope you think of Ny, Sreyneang and Wong Char and their dedication to our fashion.

We hope you join our movement and buy better from brands like Tonlé. Together we can #remakeourworld

Fashion Revolution’s theme for 2017 is Money Fashion Power which will be exploring the flows of money and structures of power across the fashion supply chain.

“There is nothing more important than performance, and fashion brands have to perform because of this greed – not a percent or two per year, but at least 10 percent quarterly, even when we’re talking about billion-dollar businesses. There is no end to the greed, so the brands are spreading themselves thin”

said trend forecaster Li Edelkoort in an interview with Deutsche Welle published this week.

Tomorrow is the fourth anniversary of the Tazreen Fashions fire in Dhaka Bangladesh. All of the garment workers were on an overtime shift to complete an urgent order when the fire alarm sounded, but managers ordered them to carry on working. As the smoke and fire spread through the building and workers eventually tried to escape, they found that iron grilles barred the windows and the collapsible gate was locked. None of the fire extinguishers appeared to have been used which suggests workers had not received fire safety training. 112 workers died and more than 200 were injured. The official who led the inquiry into the fire said

“Unpardonable negligence of the owner is responsible for the death of workers.”

After the Tazreen fire, factories were told to replace collapsible gates and lockable doors with fire-proof doors so there was always a safe exit point in the event of a fire. In the Bangladesh Accord’s initial inspection of 1600 garment factories, it was found that over 90% had lockable, collapsible gates. According to industry insiders, around 40% of all operational garment factories still have these gates, four years later.

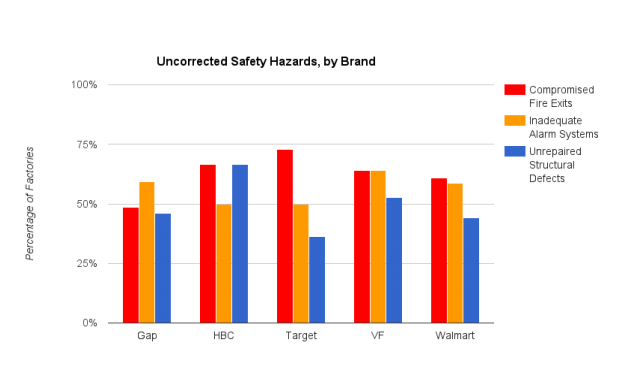

A new report published this week Dangerous Delays on Worker Safety found that of the 107 factories labelled “on track” by The Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety, 99 were still falling behind in one or more safety categories. In light of Li Edelkoort’s observation that brands are spreading themselves thin, it comes as little surprise to find that brands in the Alliance, which includes brands such as Walmart, Target, Gap inc, VF Corporation (which owns Lee, Wrangler, The North Face, Vans, Timberland and others and has just published its factory lists) have yet to put in place the life-saving safety changes they pledged following the Rana Plaza disaster, which occurred five months after the Tazreen fire. 62% of factories still lack viable fire exits, 62% do not have a properly functioning fire alarm system and 47% have major, uncorrected structural problems. Deadlines for these safety measures to be implemented were supposed to be 2014/15 but have now been moved to 2018, the end of the 5 year period over which the Alliance extends.

Are brands and factory owners really so concerned with the bottom line that they cannot afford to prioritise the installation of something so basic to worker safety as a fire-proof door and the removal of locks from existing doors?

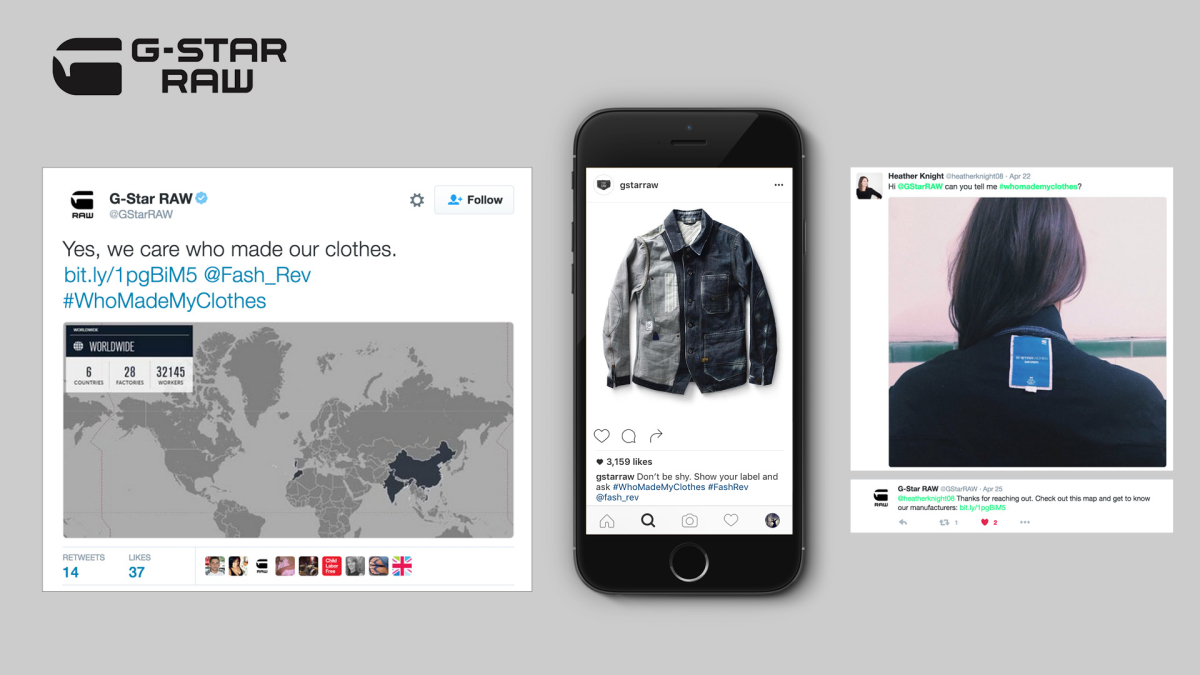

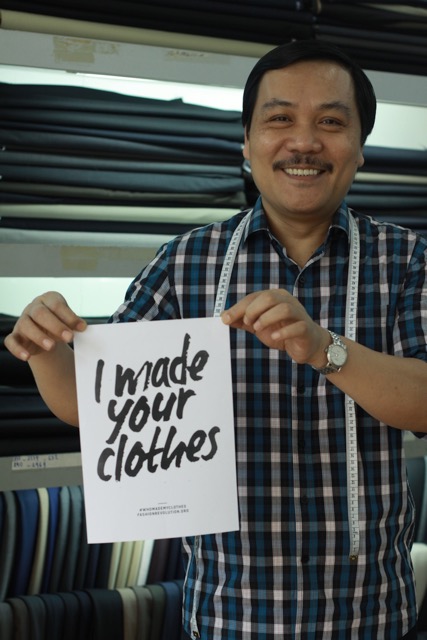

Since the Tazreen fire and Rana Plaza disaster, human rights issues are certainly more visible than ever before and there is ongoing pressure on global fashion brands to become more transparent. Companies are now being held to a higher standard and they are cognisant of this change. During Fashion Revolution Week in April, over 70,000 fashion lovers around the world asked brands #whomademyclothes on social media, with 156 million impressions of the hashtag. G Star Raw, American Apparel, Fat Face, Boden, Massimo Dutti, Zara, Jeanswest and Warehouse were among more than 1250 fashion brands and retailers that responded with photographs of their workers saying #Imadeyourclothes. Read more about our impact here.

However, the harsh reality is that basic healthy and safety measures still do not exist for millions of people who make our clothes and accessories. On 11 November 2016, 13 people died in a factory making leather jackets on the outskirts of Delhi. The front of the building had been shuttered with a metal grill which prevented the workers escaping the blaze. Deadly accidents are still commonplace in fashion supply chains and not enough has been done by brands and retailers to prevent more fashion victims; victims of neglect, oversight and the pursuit of profit.

Scott Nova, executive director of the Worker Rights Consortium says:

“What motivated Walmart and Target to do the right thing is public embarrassment. We are three and a half years on [from Rana Plaza] and they assume memories are fading.”

We have the power and, I believe a duty, to let these brands know that our memories of the Rana Plaza disaster, the Tazreen Fashions fire, and the many other tragedies which have ocurred in the name of fashion, are not fading. By asking the question #whomademyclothes we are applying pressure in the form of a perfectly reasonable question that fashion brands should be able to answer. We are asking them to publicly acknowledge the people who make our clothes; millions of people working in factories, fields, homes and other hidden places around the world. Tragedies like the Tazreen Fashions fire are preventable, but they will continue to happen until every stakeholder in the fashion supply chain is responsible and accountable for their actions and impacts.

As Li Edelkoort said, fashion brands are spreading themselves thin. As their customers, we can help make sure they start to get their priorities right and redress the imbalances of power in the fashion supply chain.

Header photo credit: A young garment worker by Claudio Montesano Casillas

Their story began with a splendid white dress shirt made by a smiling tailor in an alley of HoChiMinh City, Vietnam. Beyond the singular experience of wearing bespoke garment for the first time, it is the direct purchase from its maker that was the trigger. “Each of us now wants products that answer one’s individual needs”, says Bernard, “I hate shopping malls and I love buying unique items. I am fascinated by nice objects and the stories behind them. That’s how the idea to create an ecommerce marketplace for custom made clothes and accessories handmade in South East Asia came out.”

For the Belgo-French duo, Bernard Seys and LouAdrien Fabre., connecting consumers directly with makers creates better outcomes for everyone. As the sole vendors on efaisto.com, makers are in full control of their pricing. They receive up to 85% of what the customer pays, net of all fees.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=edHJvRvx71o&feature=youtu.be

As each item is made on demand, the makers do not have large production batches, minimum order quantities nor canevas to follow. By essence, each bespoke product has to be cut, sewn, dyed, engraved, polished or coated individually by human hands. Which results in a drastic reduction of waste or unsold products and an increased average lifetime of the product.

The buyers have the opportunity to get tailored clothes and custommade accessories at a fair prices, and know who made them.