It is not often that the life of Beyoncé and academic researchers intertwine – the chances are even more remote, when the research site in question, Sri Lanka, often rightly avoids the negativity associated with the global supply chain. Media reports record how Beyoncé justly supports the feminist cause for gender equality in pay. Yet by her braving into the world of branded gym wear (Ivy Park) to support and inspire women, she was opening herself to media scrutiny about how empowered its workers may be. While the media scrutiny may be warranted, the media’s representation of Sri Lankan workers is a partial rendering that flattens the very labour voices these interventions claim to champion.

On 8 May 2016, The Sun on Sunday carried a news item with the headlines that “Sweatshop ‘slaves’ earning just 44p an hour making “empowering” Beyoncé clobber”. Not being a reader of tabloids, I came to know of it, when an inquiry came my way from Broadly, requesting for input for a piece that it was being put together. In the hope for a nuanced intervention to the early news foray –from the Sun to the Metro, I assented. In the conversation with Siri Kale, we overviewed positive attributes to Sri Lanka’s apparel sector, signaling that it is ability to do so is associated with multiple factors – from a highly educated labour force to high standards in building regulations to protective labour legislative framework. All features of state policies in the social development and labour legislation; facets often downplayed in an age of corporate social responsibility. We also talked about the Achilles heels of Sri Lankan apparels – the lack of living wages and the inability of most workers to freely associate and enter into collective bargaining (i.e. unionise).

In the eventual output that came out of Broadly, the positives of Sri Lankan apparels or the potentially enviable Sri Lankan context was edited out. Hence, there was only one direct quote registering how MAS, a supplier/producer of Ivy Parks, has fantastic factories, is attentive to the built space, and how it is usually considered to be top of the supplier base in Sri Lankan. Otherwise, with a vaguely problematic title, the emphasis was on the lack of living wages and unionisation.

The absence of a living wage and the impossibility of unionisation are two points emphasised earlier in a report that came out of an ESRC-funded research, although there made within a context. I also emphasised how the positive adherence to ethical trade regimes and Sri Lankan apparels ability to do so having much to do with historical labour struggles, labour legislative frameworks and state policies towards our social development fabric. The centrality of labour geographies in making capitalism, à la Andrew Herod, was emphasised to accentuate how labour has agency in shaping capitalist development processes.

This nuanced reading of Sri Lankan apparels was met with wrath by an important union in Sri Lanka, with a pro-union friendly journalist hounding me with local media interventions in a bid to vilify the research. This stance was presumably because it dented the union’s ability to portray Sri Lankan apparels through a black and white lens. Shades of grey in labour politics was a faux pas, as a UCU academic member I was to learn – in a somewhat harsh way in my local research setting. Almost four years later, the partial rendering of my views by Broadly led to a message from a senior manager at one of my research sites to question my stance. While this communication was not unfriendly, I still had to point to him that the two lapses I had noted are already in the report that also helped his factory achieve a higher certification. It, however, made me then dig deeper into how this story had developed in the media.

From the Guardian to the Independent to the Telegraph, the emphasis was on Sri Lankan workers earning abysmally low amounts per hour, their slavery and the ability for consumers to change all these woes of the supply chain – where, according to the Guardian, Beyoncé was not to be blamed. Holding Beyoncé personally responsible for inequities in uneven capitalist development and the supply chain is simplistic analysis. This is beyond doubt. Yet the fact that the media and campaigners alike continue to promote the idea that consumers can single-handedly change the global labour division and continue to flatten the voice of labour by reducing workers to a homogenous category or to slaves is equally naïve. It is a representation that misses the very labour agency or conditions of possibility that made a single woman worker articulate views on empowerment and the lack thereof in her labouring life.

Feminists, Ethel Brooks and Dina Siddiqui, have emphasised this point previously and yet it continues to evade the attention of media and campaigners. The fact that Sri Lankan labour get paid a monthly minimum wage negotiated through a tripartite Wages Ordinance Board and hence are not paid an hourly wage or indeed a piece rate system was wholly absent from almost all media interventions. The woman’s description of her deplorable (private) boarding conditions is then stretched to categorize her situation as akin to slave labour. The elasticity of campaigner interpretations would require a leap of faith for any intelligent and careful reader. Nowhere in the public domain do I find the worker saying that MAS was providing boarding and that her mobility was severely restricted. Features usually absent in the Sri Lankan apparel trade, partly because many do not provide factory-based boarding facilities and partly because workers would not tolerate factories where they were locked up.

What then of Sri Lankan apparel workers? In contrast to the blasé narratives we are provided with, the reality of Sri Lankan labour is more complex and nuanced. Sri Lankan apparel sector draws upon an important and impressive social development agenda adopted by the Sri Lanka state for decades – giving the industry a highly skilled and educated labour force. It also draws upon relatively strong labour legislation, an outcome of labour struggles and movements from yesteryears, which thwarts the worst excesses of uneven capitalist development. These are facets that enable Sri Lankan apparels to make bold claims around producing “garments without guilt”; child labour, for instance, is non-existent in the industry because of state-provided free education and our legislation requires children to be in school until 16 years of age. Yet it also remains the case that with the weakening power of unions and gradual erosion to protective labour legislation, the risks for Sri Lankan apparels to fall off its cultivated mantle is real. The neglect of state protection towards labour given its absence of regulating private boarding houses or extending weekly overtime hours, equally matter in process of uneven capitalist development. Equally, so long employers have a stranglehold on the Wages Ordinance Board, worker wage increments rarely, if ever, have kept pace with inflation. The absence of a living wage then is likely to remain the Achilles heel of the Sri Lankan garment industry – making it potentially vulnerable to all other wild accusations, whether these hold water or not.

At the Copenhagen Fashion Summit last week, Juan Orlando Hernández, President of Honduras, issued the following invitation: ‘If you would like to go to Honduras to look around for yourselves, I will be personally at the airport waiting for you’.

Ignoring the heckler at the back of the room who called out ‘Mr President, stop the military from murdering community activists’ the President of Honduras launched into a promotion for his country as a leading garment exporter to the US and his ambitions for a larger European market share. The garment and textile industry is part of the newly launched Honduras 2020, a $3.4 billion project which aims to make Honduras into the country of choice for brands and retailers wishing to source sustainably. ‘We will do this through a real sustainable model focussing on key topics such as sustainable working conditions, protecting the environment, using the latest technology to reduce consumption of resources, moving from fossil fuel to renewable energy sources’ stated Juan Orlando Hernández, who continued by highlighting his country’s ambition to source 80% of its energy from renewable sources by 2020.

The commitment to reduce fossil fuels clearly doesn’t extend to the President himself, who rented a luxury jet to fly to the conference from Vista Jet, whose clients include celebrities such as Beyonce and the Beckhams. The President’s short presentation would have cost $360,000 in travel alone, according to one source, prompting dozens of critical comments on the Copenhagen Fashion Summit Facebook page.

The President continued to address the 1200-strong audience by underlining how seriously his country takes the social side of sustainability. ‘We enjoy an excellent and safe work environment and taking care of our people is our main focus and our responsibility’.

The President went on to say that Honduras was ‘the second most fair location for garment production’. After an investigatory email to the Americas Apparel Producers’ Network, I received a response from Managing Director Mike Todaro who clarified that the President was referring to the The AAPN Asia/Americas Report Card. Honduras came 2nd overall in the AAPN Report Card which is completed by sourcing executives. However, as far as I can see from online information about the Report Card, only one out of the 8 criteria relates to social compliance/sustainability and the other 7 include elements like cost, speed and product development.

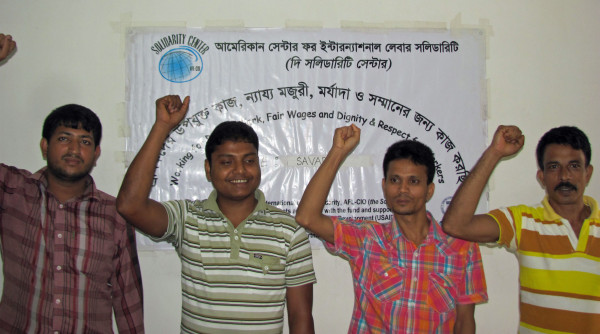

According to War on Want 53% of garment workers in maquilas, or garment factories, in Honduras are young women from deprived backgrounds who have little education. Most are unaware of their rights, exploitation is widespread and workers are actively discouraged from joining unions. The Solidarity Center says trade unionists are routinely threatened, intimidated, harassed and even murdered, with the criminals rarely brought to justice.

31 trade unionists have been assassinated and 200 injured in attacks since 2009, according to the umbrella federation for US unions AFL-CIO. In fact, in March last year the US Department of Labour issued a damning 143 page report documenting widespread and serious violations of labour rights in Honduras. The report detailed numerous cases where Honduran employers engaged in acts of anti-union discrimination, imposing non-union pacts to frustrate collective bargaining, as well as cases of non-payment of wages, forced overtime and numerous occupational health and safety violations.

On average, the wages earned in maquilas are equivalent to only 37% of the cost of the basic basket of consumer goods in Honduras. Moreover, the gap between wages for workers in maquilas and those in other industries is widening. The race to the bottom will continue unless we take a systemic approach to the issue of a living wage by working with governments and unions to set a legal, enforceable minimum wage in their country which ensures workers can meet their basic needs.

Without supply chain transparency and a commitment from fashion brand owners and factories to invest in better working conditions, living wages and workers’ rights, garment workers will remain disempowered and unable to independently negotiate labour conditions.

The garment and textile industry has undoubtedly brought jobs to the country, but not necessarily good jobs. It is often argued that any job is better than no job, but there is no reason why we can’t be creating decent jobs, jobs with dignity, without any significant impact on the retail price. The fact that people are desperate isn’t an excuse to exploit them. A Fashion Revolution is needed because brands, even the best of the brands who are working most proactively towards a living wage, will never change the system.

‘You should come see if this jobs really help people get out of poverty, with the kind of wages they make, with no labor rights. They are not even given a place to have their meals, they have to take lunch in the street and then come in back to work! Did you really believe what this man went to say to your event!’ commented RS Bruise on the Copenhagen Fashion Summit Facebook page.

So, in response to RS Bruise and all the other Honduran citizens whose commented on the visit of Juan Orlando Hernández to the Copenhagen Fashion Summit: Yes, we will come and see for ourselves #whomademyclothes. We will come and see whether Honduras really is one of ‘most fair social locations in the Western hemisphere for garment production’, as claimed in the President’s presentation.

I am ready to take the President of Honduras up on his offer to visit garment factories in his country and trust that he will keep his word. Meet me at the airport, Mr President.

H&M ha declarado la “Semana Mundial del Reciclaje” del 18 al 24 de abril de 2016 con una campaña de marketing de gran envergadura que pretende recoger 1.000 toneladas de ropa usada durante esa semana y reciclarlas para convertirlas en nuevas fibras. Fashion Revolution desafió este objetivo, señalando que sólo una pequeña fracción de las 1.000 toneladas propuestas como objetivo pueden convertirse en nuevas fibras textiles ya que la tegnología para ello aún no existe. La organización también desafió lo desconsiderado del momento para la promoción, que coincide con el 24 de abril, justo cuando hace tres años 1.134 personas murieron en Rana Plaza, en Bangladesh, haciendo ropa para cadenas minoristas, y H&M es el mayor productor de prendas en Bangladesh.

Orsola de Castro, co-fundadora de Fashion Revolution ha dicho: “Esta semana, de todas las semanas, H&M debería trabajar en solidaridad con el resto de nosotros para marcar el aniversario de la tragedia de Rana Plaza. Debería ser un momento para todos nosotros para honrar a los trabajadores textiles, aquellos que han muerto en tragedias industriales de la industria textil y aquellos que todavía hoy sufren en la cadena de suministro textil. ”

Fashion Revolution también señalaba el lenguaje confuso usado para describir el impacto de la iniciativa de reciclaje de H&M. Estábamos emocionados de que tanta gente mostrara su apoyo por una mayor transparencia y ayudara a comenzar una conversación sobre temas controvertidos relacionados con la exportación de ropa de segunda mano a países en desarrollo.

“Estamos contentos de que H&M haya admitido las verdaderas cifras de lo que se revende, lo que se reusa y lo que se convierte en nuevas fibras y de que cambiara el objetivo en su web en consecuencia. Esto ha sido algo muy influyente de hecho – usamos nuestra voz colectiva de manera moderada y hicimos que una de las mayores corporaciones del mundo diera un paso hacia una mayor transparencia.

Esperamos que H&M elimine su cupón de descuento en el futuro para no alentar un mayor consumismo entre sus jóvenes consumidores – eso sería el próximo paso lógico al abordar correctamente el tema de los residuos textiles. ”

H&M respondió con el siguiente comunicado: “Tan pronto como Fashion Revolution nos hizo conscientes de sus preocupaciones, comunicamos claramente qe no tenemos la intención de convertir en esta semana en particular como una Semana Mundial del Reciclaje de manera recurrente en el futuro, y hemos ofrecido inmediatamente elegir otra semana si hiciéramos otra Semana Mundial del Reciclaje en el próximo año o siguientes. ”

Fashion Revolution Week tiene lugar del 18 al 24 de abril en 89 países en todo el mundo. Por favor únete y ayuda a aclamar a los verdaderos héroes. Visita www.fashionrevolution.org para encontrar un evento cerca de ti. Juntos podemos hacer que el cambio ocurra.

Por favor ¡apoya a Fashion Revolution para ayudarnos a hacer nuestro mensaje más fuerte! Cada donación nos ayudará a dar voz a todos los implicados en la cadena de producción. Gracias por ser parte de este movimiento y por ayudarnos a seguir siendo fuertes.

Nota para prensa

- Millones de personas saldrán a la calle durante la Fashion Revolution Week para despertar conciencias y hacer preguntas sobre las condiciones a las que se enfrentan los trabajadores textiles y la persistente falta de derechos humanos en la industria de la moda, y para homenajear a la gente que está detrás de lo que llevamos – desde el granjero a la hilandera, la tintorera, sastres y más.

- Durante la semana del 18 al 24 de abril de 2016, te animamos a que pienses lo que hay en tu armario. Si tienes prendas sin estrenar, ¿podrías hacer algo con ellas en vez de deshacerte de ellas (en H&M o en cualquier otro lugar)? Lo podrías intercambiar con un amigo que lo aprecie más, o tal vez lo podrías modificar para que lo puedas seguir amando más tiempo. O por qué no probar nuestra Haulternative, y descubrir 8 maneras de renovar tu armario sin comprar nuevas prendas.

- Fashion Revolution Week se celebra del 18 al 24 de abril de 2016, no te olvides de preguntarle a tu marca favoria #quienhizomiropa o #whomademyclothes.

Usměvavá Kambodžanka Theavy už oblečení nevyrábí. Než se ale z řádové pracovnice organizace Sak Saum stala její národní ředitelkou, strávila dnů za šicím strojem nespočet. Nyní má Theavy za úkol koordinovat práci více než osmdesáti zaměstnanců a prodej jejich textilních výrobků. V jejím příběhu se ale zrcadlí životy mnoha dalších žen pracujících v Sak Sauk, a proto stojí za to o něm psát.

Sak Saum znamená v khmerštině důstojnost. Právě o její navrácení stejnojmenná organizace usiluje. Ženy a muži, kteří zde pracují jako švadleny nebo krejčí, mají zkušenost s obchodem s lidmi nebo jsou obchodováním ohroženi kvůli své extrémní chudobě. Theavy není výjimkou. Do organizace Sak Saum se dostala jako oběť obchodování více než deseti lety a stala se jednou z jejích prvních švadlen.

Obchod s lidmi je v Kambodži dodnes hořkou realitou zejména v chudých venkovských oblastech. Jeho obětí se stávají mladé ženy i dívky, které bývají nuceny k práci v sexuálním průmyslu, ale i muži. Ti se nechávají zlákat nabídkami práce na Blízkém Východě či ve Východní Asii, kde pak pracují za nelidských podmínek, bez dokladů a šance na návrat. Theavy byla svými rodiči prodána už jako malý dívka. Poté, co se jí podařilo utéct a žít několik měsíců normálním životem, byla znovu unesena obchodníky.

Příběh Theavy ukazuje, že obchod s lidmi není jen prázdné slovní spojení. Podle odhadů je jen v Kambodži nuceno k prostituci asi 15 tisíc žen, z nichž třetina je mladších patnácti let. O svých zkušenostech mluví Theavy nerada. Realitu nelegálního sexuálního průmyslu, kde jsou dívky drženy pod vlivem drog a pohrůžek násilí, si asi stejně nedokáže nikdo z nás představit. Když obchodníci Theavy vezli směrem k vietnamské hranici, podařilo se jí pod záminkou návštěvy toalety utéct. V drogovém opojení, s modřinami, popáleninami a rukama otlačenýma od provazů se Theavy dostala až na policejní stanici, kde se domohla pomoci.

„Strach, nulové sebevědomí a velkou touhu po tom, být v bezpečí a milována,“ tak popisuje Theavy svůj stav poté, co se jí podařilo utéct. Nucená prostituce není v Kambodži jen traumatizujícím zážitkem, ale také velkým společenským stigmatem. Ženy, které se prostitucí živily, jejich rodiny často nepřijmou zpět a v komunitě, kde žily, jen s obtížemi hledají práci a společenské uplatnění.

Pomoc a zázemí Theavy nalezla právě v organizaci Sak Saum. Ta jí poskytla ubytování, práci, vzdělání i potřebnou podporu. Zaměstnanci a zaměstnankyně Sak Saum prochází nejprve kurzem šití, poté je jim nabídnuto místo v oděvní dílně organizace. Ta sídlí v městečku Saang poblíž hlavního města Phnom Penh. Ve dvou malých budovách vznikají pod rukama zaměstnanců a zaměstnankyň organizace překrásné tašky, trička a další drobné oděvní doplňky. Součástí areálu je ale také azylový dům a vzdělávací středisko nabízející kurzy angličtiny i kurzy čtení a psaní pro dospělé.

Theavy trvalo několik let, než ze sebe setřásla nedůvěru, strach a zášť vůči lidem. Před pěti lety se Theavy vdala a záhy se jí narodil první syn. Tomu dala jméno Sokun – dar od Boha. „Chci mu dát všechno, čeho se nedostalo mně,“ říká rozhodně Theavy. Kromě naplnění svého velkého snu, se ale dočkala také pracovních úspěchů. Jako národní ředitelka organizace Sak Saum, kterou se stala, se stará o provoz organizace a snaží se předávat svou sílu těm, kteří ji aktuálně potřebují.

Markéta Nešporová

Bilkish Begum says she and other workers at a garment factory in Bangladesh could not discuss implementing fire safety measures with their employer – even after the deadly blaze at Tazreen Fashions factory killed 112 workers three years ago. Only when they formed a union, which provides workers with protection against retaliation for seeking to improve their workplace conditions, could they take steps to help ensure their safety.

“Things have improved a lot regarding fire safety once we formed union as now we have the power to raise our voice,” she says.

Bilkish, 30, now a leader of a factory union affiliated with the Sommilito Garments Sramik Federation (SGSF), is among hundreds of garment workers who have taken part in Solidarity Center fire safety trainings this year. The Solidarity Center works with garment workers, union leaders and factory management to improve fire safety conditions in Bangladesh’s ready-made garment industry through such hands-on courses as the 10-week Fire and Building Safety Resource Person Certification Training.

“I used to be afraid about fire eruption in my factory,” Bilkish says. “But after attending trainings, I feel that if we work together, we can reduce risk of fire in our factory.”

Fire remains a significant hazard in Bangladesh factories. Since the Tazreen fire, some 34 workers have died and at least 985 workers have been injured in 91 fire incidents, according to data collected by Solidarity Center staff in Dhaka, the capital. Incidents resulting in injuries include at least eight false alarms.

In January, after a short-circuit caused a generator to explode at one garment factory, Osman, president of the factory union and Popi Akter, another union leader, quickly addressed the fire and calmed panicked workers using the skills they learned through the Solidarity Center fire training. They also worked with factory management to correct other safety issues, like blocked aisles and stairwells cramped with flammable material.

Many workers who have taken part in the trainings say they are equipped to handle fire accidents.

“We are now confident after the training that we can help factory management and other workers if there is any incident of fire in our factory,” says Mosammat Doli, 35, a leader of a union affiliated with the Bangladesh Garment and Industrial Workers’ Federation (BGIWF). “From my experience at my factory, I have seen that an effective trade union can ensure fire safety in the factory as it can raise safety concerns,” he said.

Fewer than 3 percent of the 5,000 garment factories in Bangladesh have a union. And according to the International Labor Organization, 80 percent of Bangladeshi garment factories need to address fire and electrical safety standards. Yet, despite workers’ efforts to form organizations to represent them this year, the Bangladeshi government rejected more than 50 registration applications—many for unfair or arbitrary reasons—while only 61 were successful. This is in stark contrast to only two years ago, when 135 unions applied for registration and the government rejected 25 applications, and to 2014, when 273 unions applied and 66 were rejected.

Without a union, workers often are harassed or fired when they ask their employer to fix workplace safety and health conditions.

Because his workplace has a union, which enabled Doli to participate in fire safety training, he—like Osman and Popi Aktee—already has potentially saved lives. Together with other union leaders, he helped evacuate workers and extinguish a fire in their garment factory.

Shahabuddin, 25, an executive member of his factory union, which is affiliated with SGSF, is among Bangladesh garment workers who see firsthand how unions help ensure safe and healthy working conditions. He says his workplace had no fire safety equipment—until workers formed a union and collectively raised the issue of job safety.

“Now management conducts fire evacuation drills almost regularly. We did not imagine it just a few years back. As we formed union, many things started changing,” he says.

Mushfique Wadud is Solidarity Center communications officer in Bangladesh.

The three-year anniversary of the November 24, 2012, fire that killed 112 Bangladesh garment workers at the Tazreen Fashions Ltd., factory offers a time to reflect on garment workers’ ongoing struggle for workplaces where they will not be killed or injured and for jobs that will support their families.

The Tazreen fire was preventable, as was the collapse of the multistory Rana Plaza factory five months later in which more than 1,130 garments workers died and thousands more were severely injured.

Workers at Tazreen and Rana Plaza did not have a union or other organization to represent them and help them fight for a safe workplace. Without a union, garment workers say they are harassed and even fired when they raise safety issues with their employer. They are not trained in basic fire safety measures and often their factories, like Tazreen, have locked emergency doors and stairwells packed with flammable material.

Despite the many obstacles to forming organizations and achieving a voice at work, garment workers are at the forefront of pushing for change at their factories. With our strong and long-term grassroots connections in Bangladesh, the Solidarity Center allies with garment workers to provide ongoing training for factory-level union leaders on topics such as gender equality, workers’ legal rights and fire safety.

This photo essay gives voice to the sorrow, but also the hope, of the 4 million workers who toil in Bangladesh garment factories.

1. Bangladesh’s 4 million garment workers, mostly women, toil in 5,000 factories across the country, making the $25 billion garment industry the world’s second largest, after China. Yet many risk their lives to make a living. In the three years since the fatal Tazreen Fashions Ltd. factory fire, some 31 workers have died and at least 935 people have been injured in garment factory fire incidents in Bangladesh. Credit: Law at the Margins

2. Some 112 garment workers were killed in a blaze that swept through the Tazreen factory on November 24, 2012. Hundreds more were injured and like Tahera (above), will never be able to work again. Survivors say they endure daily physical and emotional pain, and often cannot support their families because they cannot work and have received little or no compensation. Solidarity Center/Mushfique Wadud

3. Tens of thousands of Bangladesh garment workers held rallies on May Day this year to highlight the need for the freedom to form worker organizations to ensure safe and healthy workplaces. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

4. With few jobs available that pay a living wage, more than 600,000 Bangladeshi workers migrate each year. Yet, “after two years, after three years, they are not getting their salary,” says Sumaiya Islam, director of the Bangladesh Migrant Women’s Organization (BOMSA). “After spending $1,000 (to labor recruiters), they are not getting paid.” Credit: Shahjadi Zaman

5. Migrants from Bangladesh also risk their lives when going overseas for jobs. In June, Bangladesh families rallied to demand the government punish traffickers after many Bangladesh workers were among migrants stranded on abandoned boats by unscrupulous labor traffickers. “I did not get anything to eat for 22 days and just survived by eating tree leaves,” Abdur said, describing his journey to Malaysia. Credit: Solidarity Center/Mushfique Wadud

6. On April 24, 2013, the multistory Rana Plaza factory collapsed, a preventable tragedy that killed more than 1,100 garment workers and injured thousands more. On the two year anniversary in April, family members and friends gathered at the site of the building to commemorate their loss. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

7. Thousands of garment workers, like Mosammat Mukti Khatun (above, looking at the Rana Plaza rubble) who survived the Rana Plaza disaster, remain too injured or ill to work and support their families. Survivors and the families of those who lost loved ones in the collapse say they are struggling to make ends meet, unable to pay rent, send their children to school or provide for other basic needs. Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

8. Days before tens of thousands of Bangladesh garment workers rallied on the two-year anniversary of the Rana Plaza collapse, the ITUC released a report that found “a severe climate of anti-union violence and impunity prevails in Bangladesh’s garment industry. The violence is frequently directed by factory management. The government of Bangladesh has made no serious effort to bring anyone involved to account for these crimes.” Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

9. The Solidarity Center launched the Bangladesh Worker Rights Defense Fund in April 2014, following an increase in violence and harassment against workers who were seeking to form unions to protect their health and rights on the job. Donations of more than $15,500 helped to provide costly medical treatment for organizers beaten or attacked while speaking to workers about their rights, and temporary food and shelter for workers fired for trying to improve their workplace. Credit: Solidarity Center/Shawna Bader-Blau

10. Despite employer and government resistance to workers’ efforts to form organizations to improve job safety, in the Dhaka export processing zone alone, 40 of the 103 factories include workers’ welfare associations, which are similar to unions. Credit: Solidarity Center/Mushfique Wadud

11. Women garment workers primarily fuel Bangladesh’s $25 billion a year garment industry, yet women are “still viewed as basically cheap labor,” says Lily Gomes, Solidarity Center senior program officer for Bangladesh. “There is a strong need for functioning factory-level unions led by women,” says Gomes, who is leading efforts to help empower women workers to take on leadership roles at factories and in unions throughout Bangladesh. Credit: Solidarity Center/Kate Conradt

12. With strong and long-term grassroots connections in Bangladesh, the Solidarity Center provides ongoing training for garment worker union leaders on topics such as gender equality, workers’ legal rights and job safety. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

13. Garment worker union leaders sharpen their skills through regular Solidarity Center workshops, such as this one on financial management. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

14. Hundreds of garment worker union leaders have participated in this year in the Solidarity Center’s 10-week fire safety certification course. “People who worked at Tazreen and Rana Plaza had no training and had no union,” says Saiful, who took part in a recent fire training. “This training is about making sure those things never happen again.” Credit: Solidarity Center/Rakibul Hasan

On 2nd December 2015, Fashion Revolution launched its first white paper, It’s Time for a Fashion Revolution, for the European Year for Development. The paper sets out the need for more transparency across the fashion industry, from seed to waste. The paper contextualises Fashion Revolution’s efforts, the organisation’s philosophy and how the public, the industry, policymakers and others around the world can work towards a safer, cleaner, more fair and beautiful future for fashion.

“Whether you are someone who buys and wears fashion (that’s pretty much everyone) or you work in the industry along the supply chain somewhere or if you’re a policymaker who can have an impact on legal requirements, you are accountable for the impact fashion has on people’s lives. Our vision is is a fashion industry that values people, the environment, creativity and profit in equal measure”

explained Sarah Ditty on behalf of Fashion Revolution.

Carry Somers, co-founder of Fashion Revolution, said

“Most of the public is still not aware that human and environmental abuses are endemic across the fashion and textiles industry and that what they’re wearing could have been made in an exploitative way. We don’t want to wear that story anymore. We want to see fashion become a force for good.”

The paper was launched at a joint event with the Fair Trade Advocacy Office in Brussels and hosted by Arne Leitz, Member of the European Parliament to mark the European Year for Development.

The event included contributions by Dr Roberto Ridolfi, Director at the European Commission Directorate-General for Development and Cooperation, Jean Lambert MEP, and Sergi Corbalán, on behalf of the Fair Trade movement.

“We need an integrated approach, from cotton farmer to consumer, and we need EU support,”

explained Sergi Corbalán.

Fashion Revolution lays out its five year agenda in the paper. By 2020, Fashion Revolution hopes that:

- The public starts getting some real answers to the question #whomademyclothes

- Thousands of brands and retailers are willing and able to tell the public about the people who make their products

- Makers, producers and workers become more visible

- The stories of thousands of actors across the supply chain are told

- More consumer demand for fashion made in a sustainable and ethical way

- Real transformative positive change begins to take root.

With many congratulations on the launch of the white paper, Dr Roberto Ridolfi proclaimed:

“My ambition, as of tomorrow, is to become a Fashion Revolutionary!”

Although our resources are free to download, we kindly ask for a £3 donation towards booklet downloads. Please donate via our donations page

[download image=”https://www.fashionrevolution.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/FRD_resources_thumbnail_whitepaper.jpg”]Download our White Paper ‘It’s time for a Fashion Revolution‘, published December 2015.

Download[/download]

Fashion Revolution also launched a new video for the European Year for Development at the event: Why We Need a Fashion Revolution.

For three years the victims of the worst factory fire to hit the fashion industry in recent times have been waiting for compensation. Now, finally, hope is on the horizon.

Around 120 garment workers burnt to death and hundreds more were injured when flames engulfed the multi-floor Tazreen garment factory in Bangladesh on 24 November 2012.

Trapped behind locked exists, workers jumped for their lives from the upper floors of the building, with more than a hundred sustaining permanent, life-changing injuries.

Like thousands of garment factories in Bangladesh, the workers at Tazreen fashions were making clothes for global retailers destined for Western wardrobes.

IndustriALL Global Union, together with the Clean Clothes Campaign, C&A and the C&A Foundation have set up the Tazreen Claims Administration Trust to compensate victims for losing loved ones, loss of income and to pay for much-needed medical treatment. Claims are already being processed and victims can expect to receive payments in the coming months.

Brands and retailers with revenue over US$1 billion are being asked to pay a minimum of US$100,000 into the fund for victims.

Certain brands that sourced from Tazreen, including C&A, Li & Fung (which sourced for Sean John’s Enyce brand) and German discount retailer KiK have now paid into the fund.

But more brands must face up to their responsibilities and pay.

That includes Walmart, Tazreen’s biggest customer. The anniversary falls just as the retail powerhouse stands to profit from US$50 billion of consumer spending on Black Friday this week.

Other brands that sourced from Tazreen and have not paid are U.S. brands Disney, Sears, Dickies and Delta Apparel; Edinburgh Woolen Mill (UK); Karl Rieker (Germany); Piazza Italia (Italy); and Teddy Smith (France).

Three years have passed but we cannot let brands forget the victims of Tazreen. Now it is time for a measure of justice.

by Christina Hajagos-Clausen, Textile and Garment Industry Director at IndustriALL Global Union. IndustriALL Global Union represents garment workers around the world. It is one of the key drivers of the Bangladesh Accord on Fire and Building Safety signed by more than 200 global fashion retailers and covering more than two million garment workers in 1,500 factories.

Photo credit: IndustriALL Global Union

I am sure that you have a closet overflowing with clothing. Chances are you might even have items that still have the swing tickets attached. Have you ever looked at the care label to see where your clothing was manufactured? Fast fashion isn’t going anywhere anytime soon. In fact fast fashion was created for this simple reason: to get us buying more and more and without much thought into where these garments are made.

I am hoping that by the time you finish reading this piece, something would have shifted. For one you will take a look at the care labels of your clothing and find out who is responsible for it and that you will hopefully reevaluate your shopping habits. Fast fashion companies cut corners, they use cheaper fabrics and cheap labor. It is simply exploitation. There is the argument that fast fashion creates jobs but when people are exploited it simply isn’t right.

Cape Town was aflutter recently when H&M (Hennes & Mauritz) opened its first store in South Africa. More stores are planned including Johannesburg’s Sandton City as well as others in Southern, East and West Africa.

It is always great to have brands open stores in our country, least of all when you know that jobs will be created. It is reported that about 600 jobs were created leading up to the opening of the V&A Waterfront and Sandton City stores. Staffers, around 60, were sent to Sweden for training. H&M plans to have as many as 1 500 people employed within the next 12 months.

The buzz continues but there is one fundamental problem with brands like these and it seems very few people know what really happens behind closed doors. In this case, behind the doors of the factories that produce these garments. This lack of knowledge was evident from the social media images from fashion bloggers to local personalities applauding H&M on their opening.

It was not long ago, in fact only two years prior, in April 2013 when the deadliest industrial disaster in the history of clothing manufacturing took place. The collapse of the Rana Plaza building in Bangladesh, claiming the lives of 1 138 of its workers.

Two years after this tragedy, H&M is still behind on correcting the fire and safety hazards in its factories in Bangladesh according to the joint report released by the International Labor Rights Forum, Clean Clothes Campaign, Maquila Solidarity Network, and Workers Rights Consortium. These fire and safety hazards are the working conditions their workers are forced to work under making sure that fast fashion reaches our stores timeously. Repairs, which include installation of fireproof doors and the removal of locking or sliding doors from fire exits are some of the issues that have not been addressed.

These are repairs that affect the staff working in these factories. If not dealt with, it could have disastrous outcomes, like that of April 2013. It appears that more attention is placed on pushing out the orders as opposed to the people who make these garments. Will these factories get away with these hazardous conditions if they were in developed countries? No! Cheap labor is simply that; cheap. Bangladeshi workers who sew for H&M toil in extremely dangerous conditions. So can you really say that their fashion is cheap? Cheap in price definitely but costly on the scale of human lives. Par Darj, the country manager for H&M South Africa described H&M’s merchandise as “democratic fashion” high quality, easy and affordable for people who ordinarily might not be able to buy fashion. How democratic is this model if H&M chose to open their first store at the V&A Waterfront? The only people who benefit from the fast fashion system are the executives who are some of the richest people in the world.

The H&M store in Cape Town is 4700 square meters and is said to be one of their biggest stores in the world. Rumor has it that there might be a section carrying local designers in the near future. Could this be why they are exploring the feasibility of opening a local manufacturing facility? Par Darj said H&M already has a production factory in Ethiopia, opened in 2014. “We will see what is possible in South Africa”. One would hope that the working conditions in this factory are safer than the one in Bangladesh or the potential of a factory opening in South Africa will not cost anyone their life.

Are South African malls in the future only going to comprise of top international brands? The likes of Burberry, Forever 21, Top Shop, Zara etc. It could be, unless you reevaluate your shopping habits.

The True Cost film will make you rethink your fast fashion addiction. I can’t help but think of the interview with Shima Akter, a 23-year-old Bangladeshi garment worker who was beaten by her factory supervisors for organizing and leading a workers’ union in the hopes to get better working conditions ‘I don’t want anyone wearing anything which is produced by our blood.’

I encourage you to watch The True Cost to understand just where your clothing comes from and the price others are paying for it.

Who Makes Our Clothing? | Livia Firth | The True Cost

In the summer of 2011, we asked people visiting the Eden Project in Cornwall, England to write postcards. The architecture of its biodomes, the placement of plants within them, and the signs and activities explaining their cultivation and use are designed to educate visitors about the plants from which many everyday things are made. We stopped passers-by to ask if they had anything on them that was made from the plants they’d seen. Typically, people would mention their clothes or shoes. So we asked them to imagine someone whose job it had been to pick their cotton or tap their rubber. What they would say to that person if they had the chance? We asked them to write this down on a postcard. Almost everyone wrote ‘thank you’ notes. It’s surprising how many people say that they’ve never thought about this before. But, for some, writing a postcard can be a tipping point, the beginning of a process in which curiosity leads to research, which leads to action.

This research process can begin by asking someone to turn an item of clothing inside out to look at the stitching. Stitching implies a sewing machine and a person whose job it is to stitch pieces of cloth together to assemble a garment. You can usually find a seam or two that are a little wavy. You can see where the loose ends of threads have been cut off. These are traces of the work done by the people who assembled that garment. You can then look at the label stitched into it. It will tell you in which country it was made. So, you know that the people who stitched it together work in Cambodia for example. The label will also tell you the materials that have been used to make it, for example cotton. But it won’t say where in the world people farmed it, turned it into cloth, dyed it, and so on. It also won’t mention the origins of its thread, dye, zips, buttons, beading or other features. Who makes these? From what materials? Where in the world? And what’s it like to work in these places? How much do people get paid for this work? What can they do with that money? How much of the price paid for that garment went to them? Who decides? How could things be different? How are things different?

One of the most pressing issues in Development Education is the need to avoid what Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie calls ‘the danger of a single story’. Learning about (un)ethical fashion should not reproduce the stereotypical ‘single story’ that all garment workers in the Global South work in dangerous and exploitative conditions, and live lives of hopeless poverty and misery. Placing learners as consumers who are, in part, responsible for these conditions can lead to senses of blame, shame and guilt that can depress, disempower and disincline them to action. ‘The problem with stereotypes’, Adichie says, ‘is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete’. So, it’s important to develop learning resources that enable the creation of multiple stories, that involve the excitement of finding things out, that surprise, take unpredictable twists and turns, that raise further questions, are underpinned by information from credible sources.

The most engaging resources are often those that latch on to ways in which students enjoy learning. Take, for example, Fashion Revolution Day’s Fashion Ethics Trump Card game. It’s a game that a group of students can be asked to make and play with their own clothes. It’s based on garment industry research by the American non-profit organization Not for Sale. Its online free2work database provides letter scores for 300 brands’ ethical trade policies, transparency, monitoring and worker rights. Here’s how it works. You start by printing out the blank cards and instructions from the Fashion Revolution Day website. Then, you ask a group of players to think about their favourite clothes, to draw pictures of them on separate cards, to look up the brands and scores on free2work, to add them to each card, to cut the finished cards out, to add them to the class’ pack, to choose four or five players, and for them to play a game.

One player takes the top card from their hand (e.g. from their Howies hoody), chooses a category that they think it will score well on (e.g. ‘policies’), calls out the score – ‘Quiksilver, policies, D+’ – and then sees which scores the other players have for their top card’s policies – ‘Howies A-’, ‘Wonderbra B-’, ‘Levi’s A’, ‘GAP A-‘. In this round, the player with the Levi’s card wins the hand, and then plays the next card. Here, for example, the referee could say that this is a ‘worker rights round’. So she could call out ‘Patagonia, worker rights C’, and the other players could respond ‘North Face D-‘, ‘Tommy Hilfiger D-‘, ‘Levi’s D+’ and ‘Adidas C’. Here there’s a draw between Patagonia and Adidas. This is when the cards’ tie-break fact would come into play. Has the brand signed the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh? Patagonia hasn’t. Adidas has. The Adidas card wins the ‘worker rights’ round. The game continues. It can stop at any time. The winner is the one with the most cards.

What’s fascinating about this game is the way that it challenges the single story of exploitative fashion brands. There isn’t one group that is equally ethical and another that is equally unethical. Fine-grained distinctions are made between brands in the game, and these differ depending on the category you choose to play. Almost without exception, a company’s worker rights score is noticeably lower than its policies score. If you want to find out why, free2work publishes brand scorecards that explain in detail how these scores were calculated. Levi’s gets a D+ for worker rights because, among other factors, it doesn’t pay a living wage, doesn’t guarantee suppliers a stable price regardless of world price fluctuations, and no suppliers are know to have independently elected trade unions. For those who want to find more than this a detailed research report is available online.

Making and playing a card game combining your own clothes with such detailed information can help to make it more meaningful, compelling, involving, and easier to remember. Anyone who has played a game of Top Trumps can recall their favourite pack, the card that beat the rest, and the one that always lost. This knowledge can stick outside the classroom, when players go shopping and think about the card they’d be able to make for their new purchase. But the kinds of actions that Fashion Revolution Day aims to encourage include, but are not limited to, ethical and sustainable shopping behaviours. We are all global citizens as well as consumers, and this is where our collective power resides. In April last year, on the first anniversary of the Rana Plaza collapse, tens of thousands of people did much more than blame their own poor shopping choices for what had happened to those garment factory workers. One of the most popular actions involved people turning their clothes inside out, taking selfies with the label showing, and tweeting them to the brands with the hashtags #insideout and #whomadeyourclothes. Some brands responded and some garment workers tweeted photos saying #wemadeyourclothes. Most stayed silent.

But actions took place in 62 countries, including an outdoor catwalk in Barcelona, Spain, a spoken word and poetry competition in Nairobi, Kenya, and a Critical Mass cycle ride in Dhaka, Bangladesh. The hashtag #insideout was the number one global trend on twitter. Teachers and their students were involved in these actions and will be again this year. This is why we have decided that Fashion Revolution Day will continue asking brands this simple question, but in 2015 it’s more personal ‘who made my clothes?’ This month we’re publishing our education packs for primary and secondary schools, further education colleges and universities, and a quiz. All of these will help teachers and students to Be Curious, Find Out, and Do Something.

Ian Cook is an Associate Professor of Geography at the University of Exeter, and runs the spoof shopping website followthethings.com. He is Fashion Revolution Day’s education lead.

Further reading

Abrams, F. & Astill, J. (2001) Story of the blues. The Guardian 29 May (http://www.theguardian.com/g2/story/0,,497788,00.html last accessed 12 February 2015)

Crewe, L. (2008) Ugly beautiful? Counting the cost of the global fashion industry. Geography 93(1), 25-33

Martin, F. & Griffiths, H. (2014) Relating to the ‘other’: transformative, intercultural learning in post-colonial contexts. Compare: a journal of comparative and international education 44(6), 938-959

Smith, J. (2015) Geographies of interdependence. Geography 100(1), 12-19

Smith, J., Clark, N. & Yusoff, K. (2007) Interdependence. Geography compass 3(1), 340-359

Links

https://www.fashionrevolution.org/resources/education/

https://www.fashionrevolution.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/FRD_trumpcards_2015_A4_.pdf

https://www.fashionrevolution.org/insideout-six-months-on/

http://followthethings.com/fashion

http://www.free2work.org/trends/apparel/

FASHION REVOLUTION RESPONDE AL ARTÍCULO EN THE GUARDIAN DE LA SEMANA PASADA

POR KARL-JOHAN PERSSON, CEO DE H&M

Lea el artículo en The Guardian aquí

Karl-Johan Persson, CEO de H&M, estaba en lo correcto cuando le dijo la semana pasada a Guardian que no hay respuestas fáciles cuando se intenta equilibrar los riesgos y oportunidades ambientales, sociales y económicas en una sociedad global compleja.

Uno debe elogiar a H&M por ayudar a impulsar hacia la mirada pública, los temas sociales y ambientales. En el mundo de la “moda rápida” corporativa, H&M está ciertamente a la cabeza en buscar soluciones sustentables. La tienda minorista está poniendo un esfuerzo y dinero significante en abastecer algodón “sustentable”, incrementar los salarios dignos para algunos de sus trabajadores de la confección, motivando a sus consumidores a reciclar la ropa que ya no usan, y desarrollando maneras innovativas de reutilizar los materiales.

Pero ¿Es realmente algo más que la línea final, como dice Persson? Él ha dicho a Guardian que, “si tuviéramos que decrecer 10% a 20% de todo lo que no necesitamos, el resultado por el lado social y económico sería catastrófico, incluyendo muchos trabajos perdidos y pobreza.”

Primero ¿De dónde proviene dicha información? ¿Dónde se encuentra su evidencia que prueba que, si todos comenzamos a comprar menos cosas baratas, las personas definitivamente perderían sus trabajos y caerían en la indigencia?

Este es un concepto arcaico de la economía capitalista. Pero por favor, en el mundo real de hoy en día la imagen global es más compleja que una simple teoría sobre la demanda agregada.

Segundo, el Scott Trust (dueño de Guardian) mantiene el valor que “la voz de los opositores no menos que la de los amigos, tiene derecho a ser escuchado”.

Finalmente y más importante, es que el mensaje público de Persson es muy peligroso. Su visión es una que reduce nuestro rol colectivo a “consumidores” en lugar de participantes activos en la sociedad diaria con voluntad y voz. Él pide un sistema en el cual las personas son sólo “consumidores” con virtualmente ningún otro propósito más que el comprar cosas. Y para mantenerse comprando, más de ello, por siempre.

Esto insinúa que nosotros como consumidores, como seres humanos, no tenemos ningún poder para cambiar la manera en que la moda es hecha y vendida. Esto simplemente no es verdad. Nosotros votamos con nuestros dólares cada vez que compramos algo, y Persson nos está diciendo que continuemos votando por un sistema que no funciona.

Si se lee entre líneas, se ve que el mensaje de Persson es puramente capitalista, por medio del cual su mayor naturaleza en infinitamente expansionario. Pero por supuesto, vivimos en un planeta con recursos finitos con millones de toneladas en textiles sin contemplaciones vertidos en vertederos de todo el mundo cada año y ropa de tienda de caridad no deseada enviada a África, diezmando a los mercados locales y los medios de vida.

Mientras H&M está elogiablemente invirtiendo en “la economía circular” y siendo pioneros en procesos de ciclo continuo que podrían tener impactos profundos por el lado ambiental, ésta no es la panacea que de repente arreglará todos los problemas que persisten en las cadenas de abastecimiento de la moda.

¿Qué sucede desde el lado de la gente? Sin importar cuán revolucionario los materiales sean, los trabajadores de la confección en muchos de los países más pobres se mantienen pegados en el ciclo de “la moda rápida” donde ellos persistentemente trabajan con tiempos de respuesta imposiblemente cortos, calificados al precio más bajo posible, en, muchas veces, condiciones que atentas contra sus vidas.

Esto también nos lleva a preguntarnos una pregunta más grande: ¿Por qué el modelo de “la moda rápida” es tan sagrado? Después de todo, es la forma de “compra de rápida solución” de producir y consumir moda lo que ha conducido a la explotación social, ambiental y creativa masiva. Y por medio del incesante marketing del millón de dólares las grandes marcas y tiendas han logrado convencer al mundo que los productos más rápidos, más baratos y masivos están de alguna manera democratizando la moda. En este sentido, la democracia significa que tenemos innumerables camisas de £5 que usamos una vez y luego botamos a costa de los trabajadores de la confección en países remotos quienes, efectivamente no tienen otra opción más que el aceptar trabajos mal pagados en situaciones precarias para alimentar los hábitos consumistas del mundo. Esto no es democrático e inevitable.

Si es cierto que las personas nacidas entre los años 80 y 90 están comprando menos, o al menos son compradores más discernidores que las generaciones anteriores, de acuerdo a lo reportado en el estudio de Intelligence Group 2014, las grandes compañías de la moda necesitan decidir, si van a promover el problema o ser parte de la solución.

¿Por qué no mejor estas grandes empresas de la moda global aran sus inversiones en revisar la línea de fondo y cómo la escala se puede conseguir de maneras fundamentalmente, alternativas? Ya es hora de pensar sobre innovar en cómo opera la moda en su nivel más fundacional. Es hora de pensar sobre el verdadero y total costo del modelo de moda rápido y barato en lugar de sólo buscar soluciones por fuera, el que aborda parte de la imagen, pero básicamente prolonga esta manera problemática de trabajar.

El lado humano necesita ser puesto en el corazón de la verdadera sustentabilidad a largo plazo porque ése es el verdadero problema de la moda. Hemos perdido la humanidad. El rol público no es solamente como consumidores y las personas que hacen ropa, no son sólo trabajadores. Todos somos humanos, y todos somos parte de la misma tela.

El camino a seguir para la industria ya no debiera ser comprar más, sino el comprar mejor. También debiera ser sobre motivar maneras honestas, abiertas y transparentes de trabajar de manera que, tanto productores, marcas y consumidores en conjunto puedan aprender de los defectos y trágicos errores (lo de Rana Plaza siendo sólo uno de muchos) y alcanzar la meta común de una industria más sustentable finalmente.

Esta es la razón por la que casi dos años atrás, cientos de personas en más de 60 países se reunieron para cambiar a la industria de la moda de adentro hacia afuera. Nos llamamos Fashion Revolution (Revolución de la Moda) y estamos trabajando hacia un futuro donde la moda sea una industria que valora el ambiente, las personas, las ganancias y la creatividad en igual medida. Mientras tanto, la visión de H&M mantiene al negocio como siempre, sólo un poco mejor.

Fashion Revolution está mostrando al mundo que los consumidores no son tan complacientes como nos hacen ver. Los consumidores quieren y merecen saber quién hace nuestra ropa y cómo, de manera que nadie esté involuntariamente apoyando o incitando prácticas dudosas y contribuyendo a un futuro que es malo para las personas y el planeta.

Nosotros creemos que el primer paso en el viaje hacia un futuro para la moda, es el de abrir la conversación. H&M publica en su página web una lista de algunas de las fábricas con las que trabajan, y es un gran comienzo. Pero nos gustaría escuchar más de parte de H&M (y otras marcas) sobre quiénes hacen su ropa. Al acercarse el 24 de Abril de 2015, Persson y su equipo deben estar preparados para responder esta pregunta fundamental.

With thanks to the team at Fashion Revolution Chile for the translation.