During the month of February, we’ve been exploring fashion’s impact on water and looking at how we can practice water stewardship through our wardrobes. So far, we’ve discussed the consequences of industrial dyes, misconceptions around water consumption, and better laundry habits to conserve water. Now, we’re taking a look at how our wardrobes affect our oceans when they release microfibres.

What are microfibres?

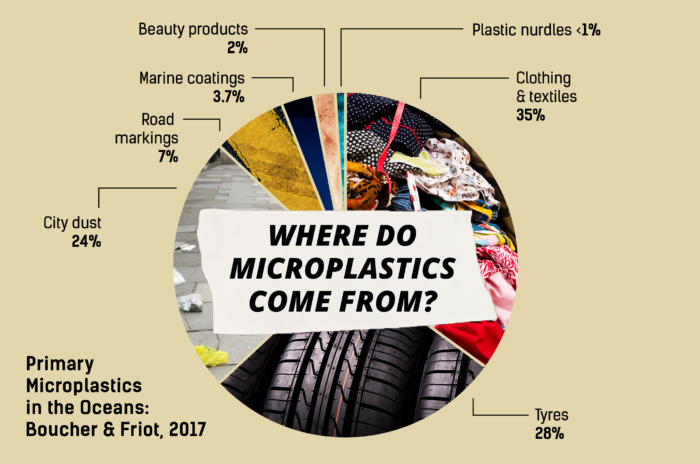

Microplastics are tiny plastic pieces that are less than <5 mm in length. Textiles are the largest source of primary microplastics (specifically manufactured to be smaller than 5mm), accounting for 34.8% of global microplastic pollution [1]. Microfibres are a type of microplastic released when we wash synthetic clothing – clothing made from plastic such as polyester and acrylic. These fibres detach from our clothes during washing and go into the wastewater. The wastewater then goes to sewage treatment facilities. As the fibres are so small, many pass through filtration processes and make their way into our rivers and seas.

Around 50% of our clothing is made from plastic [2] and up to 700,000 fibres can come off our synthetic clothes in a typical wash [3]. As a result, if the fashion industry continues as it is, between the years 2015 and 2050, 22 million tonnes of microfibres will enter our oceans [4].

What impact do microfibres have on the environment and on human health?

Due to the tiny size of microplastics, they can be ingested by marine animals which can have catastrophic effects on the species and the entire marine ecosystem.

Microfibres can absorb chemicals present in the water or sewage sludge, such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and carcinogenic Persistent Organic Pollutants (PoPs). They can also contain chemical additives, from the manufacturing phase of the materials, such as plasticisers (a substance added to improve plasticity and flexibility of a material), flame retardants and antimicrobial agents (a chemical that kills or stops the growth of microorganisms like bacteria). These chemicals can leach from the plastic into the oceans or even go straight into the bloodstream of animals that ingest the microfibres. Once ingested, microfibres can cause gut blockage, physical injury, changes to oxygen levels in cells in the body, altered feeding behaviour and reduced energy levels, which impacts growth and reproduction [5][6]. Due to this, the balance of whole ecosystems can be affected, with the impacts travelling up the food chain and sometimes making their way into the food we eat! It has been suggested that people that eat European bivalves (such as mussels, clams and oysters) can ingest over 11,000 microplastic particles per year [7].

What can fashion brands do?

The fashion industry needs to take responsibility for minimising future microfibre releases. Brands can have the most impact if they take microfibre release into consideration at the design and manufacturing stages. Designers should consider several criteria in order to minimise the environmental impact of a synthetic garment [3]:

- Use textiles which have been tested to ensure minimal release of synthetic microfibres into the environment.

- Ensure the product is durable so it remains out of landfill as long as possible

- Consider how the garment and textile waste could be recycled, to achieve a circular system.

During manufacture, there are several methods that can be applied to reduce microfibre shedding such as brushing the material, using laser and ultrasound cutting [4], coatings and pre-washing garments [1]. The length of the yarn, type of weave, and method for finishing seams may all be factors affecting shedding rates. However, much more research from brands needs to occur in order to determine best practices in reducing microfibres and create industry-wide solutions.

Waste-water treatment…

Waste-water treatment plants (where all our used water gets filtered and treated) are currently between 65-90% efficient at filtering microfibres [6]. Research and innovations into improving the efficiency of capturing microfibres in wastewater treatment plants is essential to prevent them escaping into our environment.

Washing machine filters…

Improving and developing commercial washing machine filters that can capture microfibres may allow for an additional level of filtration, whilst also educating consumers and businesses [8]. However, current filters which need to be fitted by the user, such as that developed by Wexco, are currently expensive and reportedly difficult to install. They also place a financial burden upon the consumers, rather than pressurising brands to commit to change. To tackle this, we need more industry research and legislation to ensure all new washing machines are fitted with effective filters to capture the maximum amount of microfibres possible. However, we then have the issue of what to do with the microfibres once we have caught them – an area which requires more research and industry collaboration.

Collaboration is key

Collaboration across multiple industries is required if we are to tackle microfibre pollution. In addition to material research, waste management and washing machine research and development, there is a role for other sectors such as detergent manufacturers and the recycling industry to come together to help reduce microfibre pollution. Cross-industrial agreements could help promote collaboration between industry bodies and promote sharing of resources and knowledge.

A major issue has been a lack of a standardised measure of measuring microfibre release. However, a cross-industry group, The Microfibre Consortium recently announced the first microfibre test method. The launch will enable its members (including brands, detergent manufacturers and research bodies) to accelerate research that leads to product development change and a reduction in microfibre shedding in the fashion, sport, outdoor and home textiles industries. The Microfibre Consortium also works to develop practical solutions for the textile industry to minimise microfibre release to the environment from textile manufacturing and product life cycles.

The need for microfibre legislation

Comprehensive legislative action is needed to send a strong message and force the brands to address microfibre releases from their textiles. This is a complicated issue that will require policymakers to tackle this issue on many different levels and sectors. Currently, there are no EU regulations that address microfibre release by textiles, nor are they included in the Water Framework Directive.

However, there have been several developments in microfibre legislation in the past few years:

- As of February 2020, Brune Poirson, French Secretary of State for the Ecological and Inclusive Transition, is the first politician in the world to pass microfibre legislation. As of January 2025, all new washing machines in France will have to include a filter to stop synthetic clothes from polluting our waterways. This makes France the first country in the world to take legislative steps in the fight against plastic microfibre pollution. The measure is included in the anti-waste law for a circular economy.

- In 2018, US states of California and Connecticut proposed legislation which would see polyester garments legally required to bear warning labels regarding their potential to shed microfibres during domestic washing cycles. However, this legislation is yet to be passed.

- In 2019, the EAC urged the UK government to accelerate research into the relative environmental performance of different materials, particularly with respect to measures to reduce microfibre pollution, as part of an Extended Producer Responsibility scheme. However, the UK government rejected the proposal stating that current voluntary measures are sufficient.

What can you do?

Write to your policymaker

It is vital that policy is put into place to tackle microfibres, such as the new French washing machine filter legislation. If you are concerned about microfibres, we encourage you to write to your policy representative and urge your government to take action on microfibre pollution. Now that France has enacted the microfibre legislation, it raises the bar for other governments to also take action, but they will only do so with enough pressure from the people they represent – you!

Changing your washing practices

The easiest thing you can do to minimise microfibres releasing from your clothing is to simply wash your clothes less. Given that up to 700,000 microfibres can detach in a single wash [3] ask yourself if that item really needs to be washed or can it be worn once or twice more before you do?

While some research suggested using a liquid detergent, lower washing machine temperatures, gentler washing machine settings [3] and using a front-loading washing machine [9] can reduce microfibre shedding. Researcher Imogen Napper stated they found that there was no clear evidence suggesting that changing the washing conditions gave any meaningful effect in reducing microfibre release.

You can also use a Cora Ball, a guppy bag or a self-installed washing machine filter to capture microfibres from your clothing. The CoraBall and Lint LUV-R (an install yourself washing machine filter) have been shown to reduce the number of microfibres in wastewater by an average of 26% and 87%, respectively [10]. Although these can’t solve the problem, we still want to divert as many microplastics as we can from entering our waterways.

Should we all switch from synthetic fibres?

While many people’s first instinct is to switch from synthetic materials to natural materials to minimise microfibre release, this is not always a simple choice as there are other sustainability aspects involved. The UK’s Environmental Audit Committee in their report states ‘A kneejerk switch from synthetic to natural fibres in response to the problem of ocean microfibre pollution would result in greater pressures on land and water use – given current consumption rates’ [11].

Demand brands to do more to take action on microfibres

“Ultimate responsibility for stopping this pollution, however, must lie with the companies making the products that are shedding the fibres.” states the Environmental Audit Committee [11], but there are still too many major fashion brands not taking responsibility for what happens in their supply chains and in the life cycle of their products. As well as demanding action from your policymaker, we should also ask brands what they are doing to minimize the microfibre release from their products. It is clear that there is still a lot of work to do, and as their customers, we have a lot of power in influencing the impacts of the brands we buy.

The impacts of microfibres on the environment can be mitigated, but only with systematic and meaningful change supported by policymakers, brands, industry, NGOs and citizens all working together.

References

[1] Boucher, J. and Friot, D. (2017). Primary Microplastics in the Oceans: A Global Evaluation of Sources. IUCN. Available at: https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/2017-002-En.pdf

[2] Textile Exchange (2019). Preferred Fiber and Material Market Report. Available at: https://store.textileexchange.org/wp-content/uploads/woocommerce_uploads/2019/11/Textile-Exchange_Preferred-Fiber-Material-Market-Report_2019.pdf

[3] Napper, I. and Thompson, R. (2016). Release of synthetic microplastic plastic fibres from domestic washing machines: Effects of fabric type and washing conditions. Marine Pollution Bulletin. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0025326X16307639?via%3Dihub

[4] Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2017). A new textiles economy: Redesigning fashion’s future. Available at: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/assets/downloads/publications/A-New-Textiles-Economy_Full-Report_Updated_1-12-17.pdf

[5] Koelmans, A., Bakir, A., Burton, G. and Janssen, C. (2016). Microplastic as a Vector for Chemicals in the Aquatic Environment: Critical Review and Model-Supported Reinterpretation of Empirical Studies. Environmental Science & Technology. Available at: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acs.est.5b06069

[6] Henry, B., Laitala, K. and Grimstad Klepp, I. (2018). Microplastic pollution from textiles: A literature review. Consumption Research Norway SIFO. Available at: https://www.hioa.no/eng/About-HiOA/Centre-for-Welfare-and-Labour-Research/SIFO/Publications-from-SIFO/Microplastic-pollution-from-textiles-A-literature-review

[7] Van Cauwenberghe, L. and Janssen, C. (2014). Microplastics in bivalves cultured for human consumption. Environmental Pollution. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0269749114002425

[8] Browne, M., Crump, P., Niven, S., Teuten, E., Tonkin, A., Galloway, T. and Thompson, R. (2011). Accumulation of Microplastic on Shorelines Worldwide: Sources and Sinks. Environmental Science & Technology. Available at: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/es201811s

[9] Hartline, N., Bruce, N., Karba, S., Ruff, E., Sonar, S. and Holden, P. (2016). Microfiber Masses Recovered from Conventional Machine Washing of New or Aged Garments. Environmental Science & Technology. Available at: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acs.est.6b03045

[10] McIlwraith, H., Lin, J., Erdle, L., Mallos, N., Diamond, M. and Rochman, C. (2019). Capturing microfibers – marketed technologies reduce microfiber emissions from washing machines. Marine Pollution Bulletin. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.12.012

[11] Environmental Audit Committee (2019). Fixing Fashion: clothing consumption and sustainability. House of Commons. Available at: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmenvaud/1952/1952.pdf

Research and writing by Sienna Somers, Policy and Research Co-ordinator at Fashion Revolution

The Environmental Audit Committee is launching an inquiry into the sustainability of the fashion industry.

The Committee will investigate the social and environmental impact of disposable ‘fast fashion’ and the wider clothing industry. The inquiry will examine the carbon, resource use and water footprint of clothing throughout its lifecycle. It will look at how clothes can be recycled, and waste and pollution reduced.

Mary Creagh MP, Chair of the Environmental Audit Committee, said:

“Fashion shouldn’t cost the earth. But the way we design, make and discard clothes has a huge environmental impact. Producing clothes requires toxic chemicals and produces climate-changing emissions. Every time we put on a wash, thousands of plastic fibres wash down the drain and into the oceans. We don’t know where or how to recycle end of life clothing.

“Our inquiry will look at how the fashion industry can remodel itself to be both thriving and sustainable.”

The growth of the fashion industry

According to a 2015 report from the British Fashion Council, the UK fashion industry contributed £28.1 billion to national GDP, compared with £21 billion in 2009.[1] The globalised market for fashion manufacturing has facilitated a “fast fashion” phenomenon; cheap clothing, with quick turnover that encourages repurchasing.

Environmental impact of clothing production

Clothing production consumes resources and contributes to climate change. The raw materials used to manufacture clothes require land and water, or extraction of fossil fuels. Clothing production involves processes which require water and energy and use chemical dyes, finishes and coatings – some of which are toxic. Carbon dioxide is emitted throughout the clothing supply chain. In 2017 a report by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation on ‘redesigning fashion’s future’ found that if the global fashion industry continues on its current growth path, it could use more than a quarter of the world’s annual carbon budget by 2050.

Environmental impact of purchase, use and disposal

Synthetic fibres used in some clothing can result in ocean pollution. Research has found that plastic microfibres in clothing are released when they are washed, and enter rivers, the ocean and the food chain.

Sustainability issues also arise when clothing is no longer wanted. A report by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation found that the growth of clothes production is linked to a decline in the number of times a garment is worn. Clothes disposed of in household recycling and sent to landfill instead of charity shops have an environmental impact, such as contributing to methane emissions. Charities have complained that second hand clothes can be exported and dumped on overseas markets. The UK Government has a commitment to ‘Sustainable Production and Consumption’ under UN Sustainable Development Goal 12.

Manufacturing in the UK

In recent years there has been a renewed interest in clothing that has been made in Britain. However there are concerns that the need for quick turn-around in the supply chain to facilitate the demand for “fast fashion” has led to poor working conditions in UK garment factories.

The Committee will also examine the sustainability of garment production in relation to the UK’s social and environmental commitments under the UN Sustainable Development Goals. The UK Government has a commitment to ensuring ‘Decent work and economic growth’ by protecting labour rights and promoting safe and secure working environments for all workers under UN Sustainable Development Goal 8.

Terms of Reference

The Committee invites submissions on some or all of the following points by 5 pm on Monday, 3rd September 2018.

Environmental impact of the fashion industry

- Have UK clothing purchasing habits changed in recent years?

- What is the environmental impact of the fashion supply chain? How has this changed over time?

- What incentives have led to the rise of “fast fashion” in the UK and what incentives could be put in place to make fashion more sustainable?

- Is “fast fashion” unsustainable?

- What industry initiatives exist to minimise the environmental impact of the fashion industry?

- How could the carbon emissions and water demand from the fashion industry be reduced?

Waste from fashion

- What typically happens to unwanted and unwearable clothing in the UK? How can this clothing be managed in a more environmentally friendly way?

- How much unwanted clothing is landfilled or incinerated in the UK each year?

- Does labelling inform consumers about how to donate or recycle clothing to minimise environmental impact, including what to do with damaged clothing?

- What actions have been taken by the fashion industry, the Government and local authorities to increase reuse and recycling of clothing?

- How could consumers be encouraged to buy fewer clothes, reuse clothes and think about how best to dispose of clothes when they are no longer wanted?

Sustainable Garment Manufacturing in the UK

- How has the domestic clothing manufacturing industry changed over time? How is it set to develop in the future?

- How are Government and trade envoys ensuring they meet their commitments under SDG 8 to “protect workers’ rights” and “ensure safe working environments” within the garment manufacturing industry? What more could they do? Are there any industry standards or certifications in place to guarantee sustainable manufacturing of clothing to consumers?

Deadline for submissions

Written evidence should be submitted through the inquiry page by 5 pm on Monday, 3rd September 2018. The word limit is 3,000 words. Later submissions will be accepted, but may be too late to inform the first oral evidence hearing. Please send written submissions using the form on the inquiry page.

Diversity

The Committee values diversity and seek to ensure this where possible. We encourage members of underrepresented groups to submit written evidence. We aim to have diverse panels of Select Committee witnesses and ask organisations to bear this in mind if asked to appear.

Further information

- Guidance: written submissions (including information on data protection)

- About Parliament: Select committees

- Visiting Parliament: Watch committees

Membership of the Committee:

http://www.parliament.uk/business/

committees/committees-a-z/commons-select/environmental-audit-committee/membership/

Media Information: Sean Kinsey kinseys@parliament.uk/ 07917 488791

Specific Committee Information: eacom@parliament.uk/ 020 7219 6150

Committee news and reports, Bills, Library research material and much more can be found at www.parliament.uk. All proceedings can be viewed live and on-demand at www.parliamentlive.tv

Photo credits:

Houses of Parliament and Garment Factory in Bangladesh by Carry Somers

Ocean by Ross Miller

Yesterday, the owner of the Rana Plaza factory complex and 41 other individuals were charged with murder.

In the hope that the justice system in Bangladesh will actually implement real punishment (and not succumb to internal corruption to invalidate the charges) and that the culprits will actually adequately pay for their crimes, the Twitter world has gone crazy in advocating real justice for the perpetrators, the offending big brands and even the consumers, highlighting that we are all somehow complicit in the bloodbath that was the Rana Plaza catastrophe in 2013.

Without wanting to take anything away from this eloquent and forward thinking conversation, the truth is that the big brands and the corporations are only one facet of the problem, and the reality is that there is another, unspoken abyss of so called ‘white labels’ selling unbranded clothes and accessories in vast quantities to smaller online retailers, to shops, to market stalls and even reputable fashion brands and boutiques all over the world.

These ‘white label’ sales are orchestrated by middlemen, tertiaries and distributors that are faceless, but who still peddle in misery, taking advantage of an unregulated system where the lack of transparency allows them to make massive profits and benefit from a convoluted and complicated supply chain that doesn’t safeguard workers and the environment, because there are no rules.

It goes two ways: just as the big brands cannot publish in full their supply chain contractors (and sub contractors) beyond first tier, mass producers have no way of knowing who they are selling to.

Many factory owners and brokers are unspeakably wealthy, have their own brands, often several, and many of their associates and partners operate also outside of the big brands by selling almost identical products to another invisible supply chain that we know nothing about because it is not branded, it is not part of the world of corporations and big brands, but it is nevertheless thriving.

To implement real justice, we need to understand that the issues are way more complicated than what we have been told so far, and that there are other culprits out there, who have been an intrinsic part in creating a system which is hell bent on exploitation and degradation.

For many years I was a designer with my own fashion label, and as such it was assumed that I would have the need to produce garments. I still receive dozens of emails from brokers and distributors, advertising the benefits of making cheap, high quality products through factories that I would never need to have a direct relationship with because they (the brokers and distributors) would look after it on my behalf.

I was, I still am, quite shamelessly, offered services that imply that I could grow my business rapidly, buying on trend, untraceable products, (onto which I could then apply my own label) to maximise my own profits. These emails come from companies operating from China, Bangladesh, Cambodia and Vietnam.

Premium brands, outlet stores and luxury boutiques are also taking advantage of this distribution stream, relying on the fact that their customer is no longer capable to discern a truly beautifully made piece from any old crap. This is even more sinister, as those brands and boutiques are able to achieve massive margins on a product that has cost them next to nothing.

How do we expose the fact that everybody is taking advantage of this rotten system badly in need of reform?

Of course major brands need to be accountable, and murder and ecocide are the correct words to be used to describe this scenario, but the fact is that we aren’t exposing the whole truth, because the whole truth goes deeper than anywhere we have reached so far.

The sad oxymoron of this industry right now is that the most scrutinised brands are also the ones that are investing the money and resources to actually begin to implement innovation (after all, they have a vested interest in innovating and saving their reputation), but for the health of this industry, we mustn’t stop at the big brands, but continue to question the industry and ensure that we take a much deeper look, at how we buy, who we buy from, why we continue to buy so much, and what are the real solutions to implement a positive change.

By the sheer power of their consumer visibility, the big brands and corporations should be held as an example (as I hope the owner of the Rana Plaza and his corrupt associates will be) but to put the blame solely on the household names doesn’t actually give a clear picture of the state of the industry as a whole.

What we are doing right now is to vilify a few, without exposing the rest of the problem, effectively ignoring a whole load of other actors, who are as culpable, but completely escaping our judgement.

We are letting them off scot-free.

Sure, it’s the obvious starting point, but by flagging the usual suspects we are giving them the opportunity to inject money, employ experts, and greenwash their operations, without exposing the system that has allowed them and so many others to behave abominably, outside of our scrutiny, just because we are less familiar with their names.

We need to keep advocating for governments to impose regulations, because voluntary codes of conduct are clearly not sufficient: it is only with the correct implementation of decent humane and environmental standards that we can change the fashion industry, and start to ameliorate this awful mess.

4/704 is a visual art project by Rosie O’Reilly as part of the We Are Islanders clothing label. Inspired by her Mum Catherine O’Reilly 1950-2013

There are 704 high tides a year. This installation physically recorded 4 of them and transfered the mark of their rise and fall onto garments over 48 hours highlighting our vulnerability in the face of rising sea levels.

‘4 of 704’ is a visual installation that used rising tide levels to invite discussions about our changing landscapes – physical, social and cultural. In an urban and Dublin context, cycles that exist around us, like rising tides, go mainly unnoticed until they hit a tipping point. In its physical context a rising tide line can represent a system under pressure, a breaking point. In the case of global climate change this has resulted in landmasses engulfed in water and human struggle. Irish sea levels will rise by ½ metre by the end of the century, flooding and coastal storm surges will become the norm and Dublin will face this struggle. (NUI Galway’s Ryan Institute) New York’s visit from Sandy has left the mark of rising sea levels around its bay and now an unseen tide mark exists on their economic, political and human systems as they struggle to adapt.

On a metaphorical level and in socio-cultural terms a rising tide can also represent revolt, change, stress, apathy anything that builds with time. These rising levels dominate our personal, physical and social landscapes, yet are rarely noticed until a system collapses or a risen tide falls.

The socio-cultural zone of fast fashion has increasingly been home to rising tides and tipping points. An industry engulfed in human and environmental violations – where livelihoods and habitats are played out in the game of global economics – it becomes the symbolic canvas to record 4 of Dublin’s annual 704 high tides.

There are 704 high tides a year. This installation physically records 4 of them and transfers their mark onto 7 sustainably produced garments over 48 hours on Sandymount Strand. Over two days the 7 garments constructed for this project were dipped using oceanic rhythms into a dye vat stamping them with a once-off mark; a texturized time lapse. ‘4 of 704’ aims to engage Dublin in this discussion around rising tides and the changing landscape of our time and the systemic teachings of simple structures that exist around us.

This installation has been designed in a low-tech appropriate manner using reclaimed materials where possible. The design brief is also that it is transportable and the ultimate goal is that the installation will be mobile and is installed at different costal or sea water points nationally and internationally. Each following instillation will create a different mark of a different rising tide on a different set of garments.

We are Islanders: Rosie O’Reilly, Kate Nolan, Deirdre Hynds

Design: Design Goat (Cian Corcoran & Ahmad Fakhry)

Sound Artists: The Electro Bank Collective (Mark Colbert & Mark Murphy), Slavek Kwi

Production: Susanna Lagan

Engineer: Dudley Stewart

Photography: Sean & Yvette

Dye r&d: Elisa Monahan

Built By:

Mark Colbert, Steve Reddy, Peter O’Gara, Gildas O’Laoire, Des Moriarty, Pat McIntyre, Olivia Hegarty, Sam Weber, Sean Breithaupt, Annie Howlett, Joanne O’Reilly, Rory Kennedy, Cathal Kenny, Jack Gorman, Declan Morrisey, Davan Byrne, Alison O’Reilly, Peter Murray, Trevor O’Rourke

With Thanks To:

Fundits!, Le Cool, South Studios, Shane Cox, Niamh Kirwan, Clare Nally

A film by Heather Thornton

alongcameaspider.ie