Isabela State University in Ilagan City is at the forefront of a textile revolution! The Philippine Textile Research Institute (PTRI) has set up a facility there to create yarn and thread from bamboo – a sustainable and versatile material.

This isn’t just about replacing cotton with bamboo. PTRI is blending bamboo with cotton to create unique yarns perfect for clothing. Imagine – government uniforms made with Philippine-developed, eco-friendly bamboo fabric!

Ilagan City’s commitment to sustainability aligns perfectly with PTRI’s vision. The yarn production process is automated, minimizing waste. Plus, they cleverly recycle scraps into new threads! This innovative facility produces 50kgs of yarn every 8 hours, paving the way for a greener textile industry.

The future of textiles is being woven right here in Ilagan City, and it’s made from bamboo!

El algodón es la fibra natural más importante que se produce en el mundo. Su desarrollo comenzó en el siglo XIX con el proceso de industrialización y hoy en día representa casi la mitad del consumo mundial de fibras textiles.

Las principales provincias productoras de algodón de Argentina son: Chaco, Santiago del Estero y Santa Fe. El textil también se cultiva en Formosa, Salta, San Luis, Entre Ríos y Córdoba.

En el año 1998 fue aprobado en nuestro país el uso de semillas de algodón transgénico. Desde ese momento, al igual que había ocurrido dos años antes con la soja y el maíz, el cultivo modificado genéticamente y el uso de agroquímicos crecieron sin freno. El porcentaje de algodón transgénico cultivado es casi del 100% y se ubica entre los tres principales cultivos sembrados en Argentina junto a la soja y el maíz.

- Los transgénicos multiplican el uso de herbicidas y otros agroquímicos , con las consecuencias que esto supone para el medio ambiente y la salud humana.

- Promueven un modelo de agricultura altamente industrializado que está expandiendo la frontera agrícola en zonas naturales de América Latina.

- Muchos agricultores de Argentina tienen graves problemas de control de malas hierbas, ya que las malas hierbas se están volviendo resistentes a los herbicidas asociados a los cultivos transgénicos.

- Algunos cultivos transgénicos transfieren los genes introducidos a plantas silvestres emparentadas, transmitiendo esta modificación genética, lo que afecta gravemente a la biodiversidad y plantea consecuencias imprevisibles de estos nuevos seres liberados al entorno.

Según el último informe del ICAC (Comité Consultivo Internacional del Algodón) los datos de 2019 muestran que el algodón transgénico representa el 4,71% de todas las ventas mundiales de plaguicidas, 2,91% de las ventas mundiales de herbicidas, 10,24% de las ventas de insecticidas, 1,03% de las ventas de fungicidas y 15,74% de otros plaguicidas, que incluye reguladores de crecimiento. El algodón tiene la cuota de mercado más alta de insecticidas medida por las ventas. Según algunas estimaciones, el algodón es el cuarto mercado más grande de productos químicos agrícolas en el mundo a partir de 2017.

El informe del ICAC revela que los herbicidas y pesticidas más usados en nuestro país para el cultivo del algodón transgénico son:

Cipermetrina: Además de sus efectos en el medio ambiente, la cipermetrina está catalogada como una sustancia disruptora hormonal y su toxicidad en humanos deriva en mareos, dolores de cabeza, náuseas, fatiga, irritación de la piel y en los ojos. También es muy tóxico para las abejas.

Clorpirifos: El mayor riesgo en su uso se da después de fumigar los cultivos debido a que el clorpirifos se encontrará en su nivel más elevado. Se recomienda un período de espera de 24 horas antes de entrar a los campos en donde se ha aplicado. Existe además riesgo durante el momento de la preparación. Se deben tomar las medidas necesarias para asegurar que solo una persona autorizada rocíe clorpirifos y para que durante la fumigación, aquellas personas desprotegidas permanezcan fuera del sitio en donde se aplica.

El clorpirifos puede entrar al cuerpo por los pulmones al respirar productos aerosoles o polvo que lo contienen; cuando entra de esta manera, pasa rápidamente a la sangre. También puede entrar al cuerpo por la piel, pero la probabilidad de exposición a niveles perjudiciales de clorpirifos por este medio es menor que por la inhalación o vía oral, debido a que la cantidad que entra por la piel es relativamente pequeña. La exposición cutánea si representa en cambio un mayor riesgo para la salud de los bebés debido a la textura de la piel y a que estos, al gatear o acostarse en áreas que fueron rociadas con esta sustancia, exponen una mayor cantidad de piel al clorpirifos. Los bebés que gatean en áreas recientemente fumigadas pueden también estar expuestos a mayores cantidades de esta sustancia por la inhalación de sus vapores.

Imidacloprid: Es un neonicotinoide, de tipo insecticida neuroactivo diseñado a partir de la nicotina. Los neonicotinoides son un nuevo grupo de insecticidas que actúa a través de los receptores nicotínicos. Los síntomas tras intoxicación con imidacloprid son similares a las intoxicaciones nicotínicas: fatiga, convulsiones, espasmos, debilidad muscular. En estudios hechos con ratas también se han observado letargia, problemas respiratorios, movilidad reducida, marcha insegura y temblores.

Tiametoxam: Es un insecticida sistémico de la familia de los neonicotinoides con actividad por contacto e ingestión. Posee un amplio espectro de actividad como insecticida y un gran efecto residual. Puede ser aplicado tanto por pulverización foliar como vía radical en el agua de riego. Causa irritación de los ojos y la piel. La exposición a altos niveles de vapor puede causar dolor de cabeza, disnea, náuseas, incoordinación u otros efectos del sistema nervioso central. Desde el 2018 la Unión Europea prohíbe el uso del Tiametoxam debido al daño que causa en las abejas. La decisión europea de prohibir el uso del Tiametoxam, y otros dos neonicotinoides, se dio luego de la evaluación de más de 1500 estudios científicos por parte de la EFSA (Autoridad Europea de Seguridad Alimentaria) concluyendo que en general estos productos son dañinos para las abejas. Las abejas cumplen un rol fundamental en el ambiente y su labor es importante para la producción de diferentes cultivos agrícolas, ya que son las encargadas de la polinización; la disminución de las abejas puede generar un impacto importante en la agricultura campesina, debido a que varias plantas dependen exclusivamente de la polinización para producir semillas.

En el año 2019 el INTA Sáenz Peña (Chaco) anunció que después de una década dedicada a la investigación genética lograron tres nuevas variedades de algodón de ciclo intermedio, excelente calidad de fibra y con valores tecnológicos acordes a la demanda de la industria nacional e internacional. Especialistas en algodón del INTA Sáenz Peña, Chaco– aseguraron que la nueva genética representa “un producto tecnológico especial”, dado que se logró combinar en tres variedades los eventos biotecnológicos y germoplasma adaptado a las diferentes regiones productoras de la Argentina. Se trata de Guazuncho 4 INTA BGRR, Guaraní INTA BGRR y Pora 3 INTA BGRR.

Este tipo de hallazgos científicos al igual que ha sucedido actualmente con la semilla de trigo transgénico, son presentados ante la opinión pública “como grandes avances beneficiosos para todos, ya que permiten producir productos de exportación que generan grandes beneficios económicos para el país y la creación de puestos de trabajo”. Pero la realidad es que nada de esto ocurre, los beneficios son solo para los dueños del negocio, los puestos de trabajo nunca son tantos como prometen y los perjuicios que ocasiona en el medio ambiente y en la salud de las personas que viven en los territorios donde se desarrollan estos negocios es cada vez mayor.

La cantidad de agroquímicos que se aplican en el país aumenta de manera permanente debido a la extensión de cultivos de semillas genéticamente modificadas. En la actualidad esos cultivos cubren 30 millones de hectáreas de un territorio donde viven más de 12 millones de personas adultas y tres millones de niñas y niños, siendo esta la población más expuesta a la contaminación ambiental por el uso de pesticidas. El perjuicio se agudiza en la salud infantil por los productos que más se utilizan en los campos y la forma en que se aplican. Clorpirifos, atrazina, imidacloprid, 2- 4D, paraquat, carbofuran y glifosato encabezan la lista de los pesticidas más usados en Argentina.

Argentina es uno de los países que más agroquímicos emplea por persona en el mundo. Numerosos estudios científicos han detectado restos de glifosato y otros productos, en el aire, el agua que tomamos, los alimentos, la ropa, los pañales y otros productos de higiene personal como toallas femeninas y tampones. Muchos de estos tóxicos están prohibidos en varios países del mundo, ya que está comprobado que su uso genera graves enfermedades como el cáncer, abortos espontaneos y mal formaciones.

El algodón transgénico ocupa alrededor del 70% de la superficie algodonera mundial. En la actualidad únicamente el 0,003% del algodón producido en el país es orgánico. La transición hacia un sistema de producción agroecológico es urgente. Otra realidad es posible, pero para que esto suceda necesitamos unirnos para decir basta de agronegocio.

Para Fashion Revolution Argentina por Marcela Laudonio* de @incomodaok (Autora del libro Incómoda – Cuerpos Libres, que se puede leer de manera gratuita ingresando a www.incomoda.com.ar)

*Comunicadora Social, especializada en la investigación de daños ambientales y sociales generados por la industria textil.

Fuentes:

ICAC: Comité Consultivo Internacional del Algodón.

FAO: Organización de Las Naciones Unidas para la Alimentación y la Agricultura.

Informe de Cadena de Valor Algodón – Textil (año 2017) realizado publicado por el Ministerio de Hacienda. www.argentina.gob.ar

comunicacionchaco.gov.ar

Carbono News

UTT (Unión de Trabajadores de la Tierra)

Red de Salud Popular Dr. Ramón Carrillo (Chaco)

INTA (Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria)

SENASA

The world is facing a number of unprecedented and urgent environmental crises. In January 2019 the World Economic Forum released its 14th edition of the annual Global Risks Report warning that we only have 12 years to stay under 1.5°C [1]. Rising temperatures will have a profound impact on the world’s water sources, including rising sea levels, higher risk of flooding and droughts, accelerating water scarcity, pollution, disruption of freshwater systems and more.

Water crises remain within the top ten risks to society [1]. 90% of the world’s natural disasters are water-related [2]. 2 billion people live in countries exposed to high water stress – population growth, increased water demand, and climate change are likely to exacerbate this [3].

When we talk about water crises, we consider three key dimensions:

Water scarcity – the abundance, or lack thereof, of freshwater resources

Water stress – the ability, or lack thereof, to meet human and ecological demand for fresh water; compared to scarcity, “water stress” is a more inclusive and broader concept

Water risk – the possibility of an entity (community, country, company) experiencing a water-related challenge (e.g. water scarcity, water stress, flooding, infrastructure decay, drought)

Image source: CEO Water Mandate

Water is a contextual issue, being both localised and impacting fashion businesses in different ways — through company’s direct operations, supply chains and sometimes both. This makes water a highly complex and globalised problem and one that can have significant positive impacts if solved.

Water-related risks in the global apparel sector

The apparel sector is particularly vulnerable to water-related risks because water is used throughout the production of raw materials like cotton and manufacturing processes such as dyeing, tanning, printing and laundering.

Cotton is currently estimated to be the most widely used material in the apparel industry [5], making up 33% of global textile production [6]. It is a very thirsty crop, with just one pair of jeans and one t-shirt comprising one kilogram of cotton and requiring an estimated 10,000 litres of water to produce [7].

China supplies 30% of the global cotton market and manufactures a vast amount of the world’s clothing. As a result, Chinese legislation has a huge impact on both the global economy and the planet’s ecosystems. Whilst China has adopted some of the strictest regulations on heavily polluting sectors including textiles and apparel, including its 13th Five-Year Plan for Ecological & Environmental Protection (2016-2020) and the Water Pollution Prevention and Control Law [8], it remains an important country in terms of water-related risks.

India and the United States are also large cotton producing nations, where droughts are increasingly prevalent. This can impact the global market in significant ways. For example, the last major spike in the price of cotton was in 2011, where the price per pound exceeded $1.90, up 150% from early 2010 [9]. The shortage of supply was in part linked to widespread drought conditions in China and the US. These rising costs put major fashion brands and retailers in a financially tricky position. They had to make a tough choice — they could either pass on the increased cost of cotton to price-sensitive consumers or absorb the costs in their already tight profit margins, i.e. the price of the raw material went up and so everyone along the chain potentially had to shoulder that cost.

Investors want to understand how companies are addressing water-related risks

Since then, the cotton price hasn’t reached such extremes but the impact to raw material costs remains a significant risk to apparel companies. That is why investors look to understand how well companies are preparing themselves for future price shocks triggered by water-related risks, amongst other factors. Effective water management in a company’s direct operations and across its supply chain is critical, particularly as global water resources become increasingly stressed. Good water management must include board level oversight of water-related risks and thorough water risk mapping processes.

River basins are important water sources for textile and apparel suppliers and their surrounding communities. If one company happens to be polluting the water basin upstream, the downstream residents may end up drinking and bathing in polluted and unsafe water and other downstream suppliers who rely on that river basin may be negatively affected.

Fashion companies need to understand who else is using the same water supply, what forms of agriculture rely on that water supply, whether the water supply is located in a densely populated area and what communities rely on that water source for their everyday needs. This is why fashion brands and retailers must effectively assess these risks and develop holistic water management strategies and systems, covering both direct operations and supply chains – though the supply chain is even more important, given that is where the majority of the risk lies for clothing brands.

Good water management practices are key

Companies should be setting targets for improvements in water management practices, monitoring progress and disclosing the results of their efforts in consistent and comparable ways [10]. This is the only way that fashion brands and retailers will do their part towards achieving targets 6.3 [11] and 6.4 [12] of the SDGs, which aim to improve water quality, increase water-use efficiency and protect water-related ecosystems.

This article was kindly contributed for our online course, Fashion’s Future and the Sustainable Development Goals by Emma Lupton from BMO Global Asset Management. To find out more about Emma’s work, please visit the BMO website

References

- WEF. Global Risks Report 2019. 14th Edition. 2019. Available at: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Global_Risks_Report_2019.pdf

- UNISDR. The Human Cost of Weather-Related Disasters 1995-2015. 2015. Available at: https://www.unisdr.org/2015/docs/climatechange/COP21_WeatherDisastersReport_2015_FINAL.pdf

- UN Water. SDG6 Synthesis Report 2018 on Water and Sanitation. Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters. 2018. Available at: https://www.unwater.org/publications/highlights-sdg-6-synthesis-report-2018-on-water-and-sanitation-2/

- CEO. Water Mandate, Understanding Key Water Stewardship Terms. 2019. Available at: https://ceowatermandate.org/terminology/

- FAO. Profile of 15 of the world’s major plant and animal fibres. 2009. Available at: http://www.fao.org/natural-fibres-2009/about/15-natural-fibres/en/

- FAO. World Apparel Fibre Consumption Survey 2005-2008. 2011. Available at: http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/est/COMM_MARKETS_MONITORING/Cotton/Documents/World_Apparel_Fiber_Consumption_Survey_2011_-_Summary_English.pdf

- Mekonnen MM, Hoekstra AY. The green, blue and grey water footprint of crops and derived crop products. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci. 2011;15(5):1577–600.

- China Water Risk. Today’s fight for the future of fashion: Is there room for fast fashion in a Beautiful China? 2016. Available at: http://www.chinawaterrisk.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/China-Water-Risk-Brief-Todays-Fight-for-the-Future-for-the-Future-17082016-FINAL.pdf

- Financial Times. Cotton prices surge to record high amid global shortages. 2011 Feb 11. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/3d876e64-35c9-11e0-b67c-00144feabdc0

- CEO Water Mandate. Exploring the case for corporate context-based water targets. 2017. Available at: https://www.ceowatermandate.org/files/context-based-targets.pdf

- Sustainable Development Goal 6 Clean Water and Sanitation, Target 6.3; By 2030, improve water quality by reducing pollution, eliminating dumping and minimizing release of hazardous chemicals and materials, halving the proportion of untreated wastewater and substantially increasing recycling and safe reuse globally.

- Sustainable Development Goal 6 Clean Water and Sanitation, Target 6.4; By 2030, substantially increase water-use efficiency across all sectors and ensure sustainable withdrawals and supply of freshwater to address water scarcity and substantially reduce the number of people suffering from water scarcity.

by Emily McCoy, Fairtrade

The fashion industry is notorious for exploiting it’s garment workers and cotton farmers. Only a tiny percentage of the money we pay for clothes ends up in the hands of those who made them. Farmers are often left invisible, neglected and poor at the end of a long and complex supply chain.

Why should you care about sustainable fashion? Take it from someone who knows best what sustainable sourcing can do. Phulme is a cotton farmer working for a Fairtrade certified co-operative.

Phulme lives in the remote Bolangir district in the Odisha state of eastern India where her community, the Pratima Organic Growers Group, farm sustainable cotton. Her co-operative is made up of 2,088 individual members spread across 72 villages. Until now, they received little contact from the outside world and lived in relative poverty.

The Pratima co-op have been Fairtrade certified since 2010. They are a democratic society and every three years choose a chairperson to speak on behalf of, and lead, the group. That person is Phulme Majhi, and she talks to us about being a woman who leads the Pratima Group, and explains some of the challenges, both environmental and social, that they face.

Sustainable Fashion Empowers Women

‘I was elected as the chairperson of our co-op. There was a voting process between a male farmer and myself, and I won! I was very apprehensive in the beginning, being a women, I wondered how I would manage to deal with the men on the board. I was very afraid and scared. But I am not afraid anymore.’

‘Now we can walk shoulder to shoulder with men. We [women] have access to finance and the confidence to handle our own finances, whereas in the past we relied on men. We get training and we can meet visitors – this gives us more confidence in ourselves. We are able to fulfill our needs ourselves, and not be dependent on men.’

Fairtrade provides co-ops like Pratima with training and support to give farmers the opportunity to improve their lives. Phulme was also involved in a women’s group with other women in her village.

‘We were educated about the benefits of a women’s group and asked to set-up our own. I spoke to the other women and explained the benefit we would get from this group. This group taught us to realise our own strength, and that we can go outside of our homes and village, that we can go to the bank and attend meetings.’

‘Before I was restricted to my house and I did not do anything. I used to do domestic work like cooking and looking after the children, and helping at the farm – that was all.’

Fairtrade helps farmers and workers learn about women’s empowerment, making sure people have basic human rights like education and equal rights. With money from their Fairtrade Premium, Pratima also gives cash scholarships to 600-700 school students each year. Phulme speaks enthusiastically about how the women’s group she is part of gave her the confidence to become the chairperson for the whole society.

Sustainable Fashion Empowers Farmers

In Odisha, cotton farmers face drastic environmental challenges. It is a hilly area, where only cotton can grow on the steep slopes and poor soils. They grow a little rice and some pulses as staple crops in flatter places, but rely on cotton for their basic needs. Sometimes there is no opportunity for any crop during the second part of the year and people may have to leave their homes and look elsewhere for work.

‘There used to be no rainfall. We have a problem with rainfall. We have received facilities to help this – Fairtrade has helped to build a water storage unit to preserve rainwater.’

‘We have also learnt about agricultural practices like composting, which we were not doing ten years ago. We now know about better farming practices, we used to till the land manually and now we have access to tractors. In summers we still face a lot of problems with lack of water. During the rainy season it is OK, but afterwards we are facing a lot of problems.’

Learning and Growing

Cotton harvesting takes place over two months, from December to January. Each farm sees two to three pickings and the produce is stored temporarily until the final picking is complete.

The co-op representatives take samples from each farmer for quality checking and then farmers take the cotton to the resource centre, where the collected cotton is taken to the gin for processing. The gin is a machine that separates cotton fibers from their seeds. The resource centre has a weighing machine where the farmers weigh the cotton themselves and then it is again weighed at the gin in front of a farmer representative. Payment is made directly to the farmer’s bank account – something Phulme is proud to be able to manage for herself.

During processing, meticulous care is taken to ensure the integrity and traceability of the Fairtrade cotton.

‘Fairtrade gives us training in how to tackle our problems. We have also had the opportunity to meet with other groups and businesses. Through this exposure, and being associated with Fairtrade, we have the confidence to speak to people and other officials. Previously we would just depend on what we were told, but now we can decide for ourselves.’

‘We are a very small village, no-one used to come to meet us, and now lots of people come to see us. We all really like it when someone comes to visit!’

Support cotton farmers like Phulme by buying clothes and homeware made with Fairtrade cotton.

So what does community based political organisation (i.e. the kind that got Obama elected) and The Fashion Revolution have in common? Actually much more than you’d think.

The strength of Fashion Revolution Day is that it is a movement made up of hundreds and thousands of people each telling a story — of how garment workers and farmers made our clothes, of our deliberate decision to support conscious fashion and our collective efforts to spread more ethical practices.

Most often we are talking to each other — which is a good thing — but a key outcome of Fashion Revolution is, and should continue to be, getting other people to join us (a.k.a ‘growing the movement”) in transforming the fashion industry. But what is the most effective way of doing that?

I don’t come from a fashion background and so my entry into the eco-fashion world is rooted firmly in my training as an academic and as an activist. And as an activist, I bristle, alongside everyone else reading this blog, at the continued love affair our society has with cheap fast fashion. We all know the story. And the excuses.

So when we come across these pro- ‘Fast Fashion’ arguments from our friends and family and co-workers, what do we do? Turns out, the big “P” political movement (i.e. the ones that get people elected to parliaments) have a wealth of tools that can help us, as Fashion Revolutionaries, to start to break down these ‘Fast Fashion’ arguments. Chief among them is something called “the story of self”.

Let me explain.

Progressive political campaigners in their work argue that you can no longer win people over by presenting them with facts and figures. Facts and figures are still important, but they are not enough. Rather, we win people over by tapping into their core values and showing how these values can be expressed by joining in our Movement. And the most effective way of doing that, is by expressing our core values and engaging people on the story of why we are involved.

Ever been motivated into action by thinking “What if that was my child working in the factory?” or “how would I feel if my workplace was unsafe” or “what if that river was the source of my drinking water?” Then you already know what I am talking about.

Usefully, campaign theory (yes, there is such a thing!) gives us a neat little template, which we can use to tell a story about our ‘conversion’ to eco-fashion and, through this, engage people in a story that links the Fashion Revolution with the values important to them. It is about telling your story of why you are involved and it goes something like this.

- First, describe a challenge that you came across in the fashion industry that really motivated you to act. Did you look at the huge amount of waste in the fashion industry and think there has to be a better way? Or did you read the child labor statistics and think “what if that was my child”? Did you look at the water pollution from garment factories and thing I wouldn’t want to drink that?

- Second, describe your response to the challenge you saw. What choice did you make once your knew about the challenge? What different path did you see? Did you decide to cut back on your clothing purchases? Did you switch to upcycled/recycled/second hand or ethically made clothes? DId you learn how to repair your old clothes? Did you join Fashion Revolution (answer: yes!)

- Finally, provide the person you are talking with an opportunity to act — ask people to do something. Something small, this is not the time to overwhelm them with the challenge we face, but just something to get them started on making better clothing choices. For example, you could ask them to read the stories on the Fashion Revolution website.

See what you’ve done? You’ve described a situation that challenges an important universal and relatable value (desires to minimise environmental stress, prevent child welfare, or ensure clean drinking water), described how you changed (the person everyone can relate to because they are your friend, family or co-worker) and provided a template for your audience to follow suit.

You’ve provided motivation for change and a path forward to do so. And it shouldn’t take long – the whole story from start to finish should be about 2-3 minutes max.

If you want to explore more about this tool, and many others, Wellstone is a goodplace to start.

So, that’s the theory.

What does it look like in practice? Check out my story.

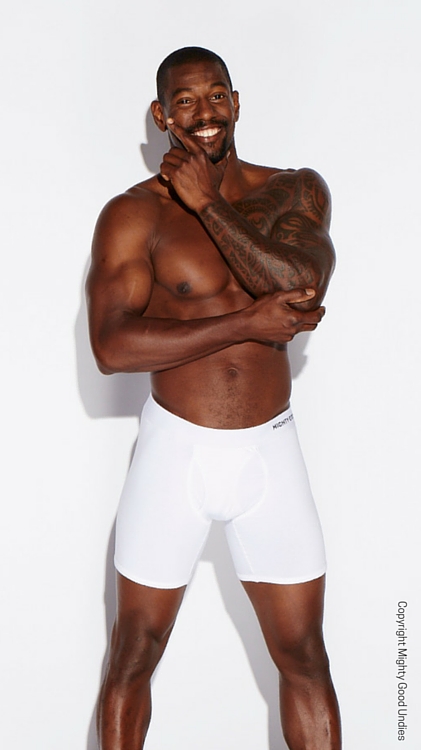

The story of my eco-fashion underwear brand Mighty Good Undies, started with my visit to India. I knew the facts and figures of the cotton industry and the potential benefits of certified organic and Fairtrade cotton, but at that stage it was all rather cerebral.

But it was only when I was sitting in the fields with the farmers from a Chetna Organics cooperative did I really get it: these people wanted to grow and sell organic cotton because organic farming meant they didn’t get sick all the time. And I realised ‘what if it was me getting sick at work?” Wouldn’t I want to change that?

And then the farmers added the kicker: many farmers wanted to join Chetna Organics but their ability to convert to organic cotton was limited by the demand for their product.

Well, I was hooked.

At that moment, I made a choice that I need to find ways to grow markets for organic and Fairtrade cotton so that more farmers, and more workers in Chetna’s production partner Rajlakshmi Cotton Mills, can get the benefits of this alternative form of trade and production*.

As the song says “From little things, big things grow…”

Happy Fashion Revolutionising

Hannah, Co-founder, Mighty Good Undies

* Okay, so starting a new ecofashion brand is probably not an option for most people, so you may want to start off with some of the brilliant suggestions in the book “How to be a Fashion Revolutionary” from the Fashion Revolution Website.

On 2nd December 2015, Fashion Revolution launched its first white paper, It’s Time for a Fashion Revolution, for the European Year for Development. The paper sets out the need for more transparency across the fashion industry, from seed to waste. The paper contextualises Fashion Revolution’s efforts, the organisation’s philosophy and how the public, the industry, policymakers and others around the world can work towards a safer, cleaner, more fair and beautiful future for fashion.

“Whether you are someone who buys and wears fashion (that’s pretty much everyone) or you work in the industry along the supply chain somewhere or if you’re a policymaker who can have an impact on legal requirements, you are accountable for the impact fashion has on people’s lives. Our vision is is a fashion industry that values people, the environment, creativity and profit in equal measure”

explained Sarah Ditty on behalf of Fashion Revolution.

Carry Somers, co-founder of Fashion Revolution, said

“Most of the public is still not aware that human and environmental abuses are endemic across the fashion and textiles industry and that what they’re wearing could have been made in an exploitative way. We don’t want to wear that story anymore. We want to see fashion become a force for good.”

The paper was launched at a joint event with the Fair Trade Advocacy Office in Brussels and hosted by Arne Leitz, Member of the European Parliament to mark the European Year for Development.

The event included contributions by Dr Roberto Ridolfi, Director at the European Commission Directorate-General for Development and Cooperation, Jean Lambert MEP, and Sergi Corbalán, on behalf of the Fair Trade movement.

“We need an integrated approach, from cotton farmer to consumer, and we need EU support,”

explained Sergi Corbalán.

Fashion Revolution lays out its five year agenda in the paper. By 2020, Fashion Revolution hopes that:

- The public starts getting some real answers to the question #whomademyclothes

- Thousands of brands and retailers are willing and able to tell the public about the people who make their products

- Makers, producers and workers become more visible

- The stories of thousands of actors across the supply chain are told

- More consumer demand for fashion made in a sustainable and ethical way

- Real transformative positive change begins to take root.

With many congratulations on the launch of the white paper, Dr Roberto Ridolfi proclaimed:

“My ambition, as of tomorrow, is to become a Fashion Revolutionary!”

Although our resources are free to download, we kindly ask for a £3 donation towards booklet downloads. Please donate via our donations page

[download image=”https://www.fashionrevolution.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/FRD_resources_thumbnail_whitepaper.jpg”]Download our White Paper ‘It’s time for a Fashion Revolution‘, published December 2015.

Download[/download]

Fashion Revolution also launched a new video for the European Year for Development at the event: Why We Need a Fashion Revolution.

It still strikes me as profoundly wrong that even though cotton is the world’s oldest commercial crop and one of the most important fibre crops in the global textile industry, the industry generally fails to focus on the entire value chain to ensure that those who grow their cotton also receive a living income.

Up to 100 million smallholder farmers in more than 100 countries worldwide depend on cotton for their income. They are at the very end of the supply chain, largely invisible and without a voice, ignored by an industry that depends on their cotton.

When it comes to clothing, companies’ supply chain engagement was once limited to who their importer was. Now they are engaging with their supply chain more and have better awareness of the factories used to manufacture their end products. Even before the Rana Plaza disaster of 2013, there had been increased attention on improving the conditions experienced by textile factory workers thanks to campaigns such as the Clean Clothes Campaign.

Some companies also have awareness beyond the factories and these are all movements in the right direction. However, even those mindful of the difficulties faced by factory workers, tend to miss the first links in the supply chain.

Maybe this is because cotton farmers continue to somehow lose out in both the so-called ‘sustainable’ and ‘ethical’ fashion debates. When companies talk about ‘sustainability’ in their clothing supply chains, they are generally looking at the environmental impact of sourcing the raw materials. Meanwhile in ‘ethical’ conversations about the many livelihoods touched by the garment value chain, companies generally refer to factory workers, again overlooking the farmer who grows the seed cotton that goes into our clothing.

The reason we need to keep insisting that cotton farmers are an important part of the fashion supply chain is because cotton is failing to provide a sustainable and profitable livelihood for the millions of smallholders who grow the seed cotton the textile industry depends on. Just as it’s important for us to take home a living wage, to help bring a level of security for our families and the ability to plan for the future, I would argue that this is even more vital for people living in poorer countries where there is little provision for basic services such as health and education or the safety net of social security systems to fall back on.

As a global commodity, cotton plays a major role in the economic and social development of emerging economies and newly industrialised countries. It is an especially important source of employment and income within West and Central Africa, India and Pakistan.

Many cotton farmers live below the poverty line and are dependent on the middle men or ginners who buy their cotton, often at prices below the cost of production. And rising costs of production, fluctuating market prices, decreasing yields and climate change are daily challenges, along with food price inflation and food insecurity. These factors also affect farmers’ ability to provide decent wages and conditions to the casual workers they employ. In West Africa, a cotton farmer’s typical smallholding of 2-5 hectares provides the essential income for basic needs such as food, healthcare, school fees and tools. A small fall in cotton prices can have serious implications for a farmer’s ability to meet these needs. In India many farmers are seriously indebted because of the high interest loans needed to purchase fertilisers and other farm inputs. Unstable, inadequate incomes perpetuate the situation in which farmers lack the finances to invest in the infrastructure, training and tools needed to improve their livelihoods.

However research shows that a small increase in the seed cotton price would significantly improve the livelihood of cotton farmers but with little impact on retail prices. Depending on the amount of cotton used and the processing needed, the cost of raw cotton makes up a small share of the retail price, not exceeding 10 percent. This is because a textile product’s price includes added value in the various processing and manufacturing activities along the supply chain. So a 10 percent increase in the seed cotton price would only result in a one percent or less increase in the retail price – a negligible amount given that retailers often receive more than half of the final retail price of the cotton finished products.

Within sustainable cotton programmes, Fairtrade works with vulnerable producers in developing countries to secure market access and better terms of trade for farmers and workers so they can provide for themselves and their families.

Our belief is that people are increasingly concerned about where their clothes come from. This year we visited cotton farmers in Pratibha-Vasudha, India, a Fairtrade co-operative in Madhya Pradesh. We saw the safety net that Fairtrade brings; the promise of a minimum price that works in a global environment. The impact on prices of subsidised production in China and the US adds to unstable global cotton prices. These farmers democratically decide how the Fairtrade Premium is spent: on training to improve soil and productivity, strategies to mitigate the impacts of climate change and on the most important ways for their communities to benefit, such as building health centres and educating children.

Consumers want their clothes made well and ethically, without harmful agrochemicals and exploitation. We think about farmers when we talk about food. Let’s start thinking about farmers when we think about clothing too.

Image credits: Trevor Leighton.

On Monday 29 June 2015 in the UK House of Lords, industry leaders, press and political leaders attended the roundtable debate Ethical Fashion 2020: a New Vision for Transparency. The aim of the event was to help to shape a vison of what transparent supply chains could look like in five years time and set out what steps are needed to transform the fashion industry of the future.

The event at the House of Lords, now in its second year, was co-hosted by Fashion Revolution, the Institution of Occupational Safety and Health (IOSH) and the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Ethics and Sustainability in Fashion.

Introducing the event, IOSH Chief Executive Jan Chmiel said

“Transparency matters because it can drive improved workplace standards. It can also increase recognition of good health and safety performance. And importantly, it can help ensure more people view health and safety as an investment, not a cost – one that saves lives, supports business and sustains communities. Whereas, a lack of transparency can do the reverse. Crucially, it can mean that firms don’t know the factories that are supplying them, so they can’t actively manage their risks – potentially leading to tragedy, disaster and business failure”.

Co-founder of Fashion Revolution, Carry Somers, set the scene as to why transparency is a crucial issue to address over the next 5 years

“So much is hidden within the industry, largely because of its scale and complexity. The system in which the fashion and textiles industry operates has become unmanageable and almost nobody has a clear picture how it all really works, from fibre through to final product, use and disposal.

The low or non-existent levels of visibility across the supply chain highlight the problematic and complex nature of the fashion industry. A few brands have received a lot of public pressure to publish information about their suppliers and some have responded by disclosing parts of it. Yet, the rest of the industry remains very opaque. It’s not just brands; it’s the myriad other stakeholders along the chain too. We believe that knowing who made our clothes is the first step in transforming the fashion industry”.

The two hour debate, chaired by Lucy Siegle, acknowledged where progress needed to be made, highlighted opportunities for change and set out a vision for how the fashion industry could and should look by 2020.

Some of the key points made by the speakers are set out below:

Peter McAllister, Executive Director of the Ethical Trading Initiative

- We need to break down what transparency looks like and define what the journey looks like, so we get a virtuous circle.

- Smart regulation drives behaviour. Once the environment is predictable, business can work within that environment. What is difficult is when business can’t predict when wages will rise or fall, when there will be a strike, etc.

- We need mechanisms where workers are represented not where they are just at the receiving end of good intentions

- We want to see the UN Guiding Principles on Human Rights become a rallying call to transform fashion industry and see this fully implemented by 2020. Companies need to undertake human rights due diligence, understand the impacts and take the remedial action required. This underpins the need for transparency.

- We can’t wait for a crisis – we need to put national and private mechanisms in place. We need to set up platforms in key places such as China and India to influence change in producer countries.

- Bangladesh is still a young country with weak infrastructure. The Accord and the Alliance were the right response at the right time. It is an attempt to turbocharge the effort of the Bangladesh government to set up their own mechanisms. It is designed to be a contribution to a longer term shift, of which we are yet to see the green shoots.

- Transparency is coming at companies, whether they like it or not – better to get ahead of the curve. The best way to get change is to inspire competition between companies.

- This sector is well overdue transformative change, not just twiddling at the edges

Rob Wayss – Executive Director of The Bangladesh Accord

- Accord signatories were placing “unprecedented” requirements on their suppliers.

- Even though there had been a positive response to the Accord, much more needs to be done including the increasing the pace of remediation works in factories and ensuring workers are able to raise safety concerns without fear of reprisal. If other workers see that raising safety concerns leads to hassle, they won’t express worries themselves.

- The Accord is based on a 5 year agreement. Health and Safety Committees have been put in place in all factories, remedial action is being taken, factories are working with union representatives.

- Transparency is the key to progress and the way the Accord works. We publish inspection and disclose non-compliance.

- Inspections for the Accord were carried out by world class engineers who worked alongside Bangladeshi engineers. I would like to see the assessments based on scientific engineering principles.

- Money, resources and political will are needed to change the way we do business.

- A kite mark on garments to verify ethical production would be very difficult as would need to verify what is the standard, who is assessing and monitoring. It is very high risk and it is not very meaningful, even though there is an appetite for this amongst consumers.

- The media has an important role to play as it creates pressure. Where there are legitimate article expressing valid criticisms, we respond accordingly. However, some articles in the Bangladeshi press were perhaps generated by factory owners who wanted to see the pace of the Accord slowed down.

Baroness Young of Hornsey – All-Party Parliamentary Group on Ethics and Sustainability in Fashion.

- You can only make a choice if you have information and that information turns to knowledge

- More businesses need to be more honest.

- We need to think more creatively and outside of the box of usual business models.

- Legislation won’t solve the whole problem but it can promote cultural change, as we’ve seen with the Equality Act.

- The government had to be encouraged to put the transparency clause in the Modern Slavery Bill in place by business. Loopholes in law which still exist around Modern Slavery Act will be stricter by 2020.

- The fashion industry is different to other industries as it has such a widely distributed supply chain. I’d like to see pressure building so companies can make progress on their public statements over the next five years as to how they are addressing modern slavery within their supply chains.

- We need more empowerment of consumers, business and politicians so this becomes so much part of life that we don’t need to think about it.

- The idea of a kite mark on the surface seems attractive but it simplifies what is an incredibly comples area. How do you make calculations which balance the social and the environmental?

- We can’t assume Made in Britain is OK. One member of the APPG saw conditions in a garment factory in East London last week as bad as those you would see anywhere in the world.

Simon Ward – British Fashion Council (BFC)

- The BFC has a three-year strategy to put sustainability at the heart of all we do. BFC is undertaking a collaboration with Marks and Spencer through the Positive Fashion initiative to promote best practice in order to stimulate real and meaningful change, highlighting the practical toolkit for designers which incorporates sustainability.

- There is a a need to find creative solutions and look at things differently. For instance, the BFC worked with the government to set up a draft standard on fashion apprenticeships as a solution to the problem of unpaid interns.

- We’re on an endless hamster wheel, more & more, cheaper & cheaper. How can we break the madness & tell a positive, creative story? People warm to the story and telling the story behind an item of clothin is an entrancing way to give insight into the people behind the clothes. It provides a compelling motivation for change.

Garrett Brown of the Maquiladora Health and Safety Support Network

- We need public listing of supply chains

- We need public disclosure of monitoring timelines and remedial action

- We need meaningful participation by workers, including training to give them the information and authority to act without retaliation.

- Sourcing is currently driven by the lowest price, highest quality, fastest delivery, with a window dressing of CSR.

- It is a pre-requisite that governments have the will and the resources to enforce the regulations, but in most places in the developing world this isn’t the case. In Bangladesh, it should be the government enforcing regulation and the Accord is a real step towards achieving this. Mexico has strong health and safety legislation, as strong as the US, but it has high foreigh debt, so won’t do anything to deter investents. This is why workers need to protect themselves.

- Transparency is only as good as the information that you get

Finally, Lucy Siegle asked the panellists what one thing would make a massive difference by 2020?

Garrett Brown: The Accord model of public discoloure is critical. Brands have to disclose where their factories are and tell us about the conditions.

Simon Ward: A lot of big and complex change is required. We need a magic story to tie it all together so it is understandable.

Baroness Lola Young: Information leading to activism. Supporting organisations like Fashion Revolution which are build on the work of other organisation like the EFF, ETI, Labour Behind the Label. Information needs to be acted on and we need coalitions like Fashion Revolution which can lobby for change.

Rob Wyass: Audits, credibly performed

Peter McAllister: The ETI has made a commitment to develop a public form of the audits of their companies which we hope will showcase some of the best performers.

After the debate, guests adjourned to River Room, overlooking the Thames, for a drinks reception and networking. Baroness Lola Young and Lord Speaker, Frances de Souza, both gave speeches at the reception and many of the guests were filmed for an upcoming series of mini films being produced and directed by Fashion Revolution as part of the European Year for Development.

The event at the House of Lords brought together many of the key people from within the fashion industry and beyond who are at the forefront of creating meaningful change. The challenge now is to translate the vision set out for transparency in 2020 into a reality in order to transform the fashion industry of the future.

Photo credits: Arthur & Henry, Zoe Hitchen, Orsola de Castro and IOSH

Meet Kady Waylie this International Women’s Day.

Kady is one of West Africa’s 10 million cotton farmers. She and her family grow their own food, but their cash comes from growing cotton.

The farmers’ group in Kady’s village in Senegal began to see benefits of Fairtrade with training courses they were given, to produce better quality cotton, to get higher yields, to improve health and safety.

When it comes to harvest time, they are paid a guaranteed price for their produce, above the market price. And the farmers’ group is also paid the Fairtrade Premium – the extra money that the group decides how to spend, men and women together.

The Premium has been used in Senegal to help many of the women and girls in the community – to build and furnish schools, and to buy packs of stationery, books and schoolbags for students. Some has gone on projects for clean drinking water. Some has been spent helping build and equip clinics, and to train villagers in health care and midwifery.

The processes involved have made groups of cotton farmers stronger and more able to look after their own interests, to deal with government officials, to engage with other groups.

Whilst International Women’s Day represents an opportunity to celebrate the achievements of women around the world, sadly it’s not all good news.

Kady’s cooperative, and many others, are desperate to sell more of their cotton on Fairtrade terms because are not earning nearly enough from Fairtrade sales to lift them out of terrible poverty.

The price of cotton has slumped in the last 30 years, even though the cost of producing it has risen and that means farmers in places like Uganda, India, Kyrgyzstan and West Africa are struggling to survive.

Cotton farmers are at the end of a long and complex supply chain in which they are virtually invisible and wield little power or influence. With high levels of illiteracy and limited land holdings, many cotton farmers live below the poverty line and are dependent on the middle men or ginners who buy their cotton, often at prices below the cost of production.

Practically speaking, farmers selling cotton on Fairtrade terms receive a Fairtrade Minimum Price for their cotton, which acts as a vital safety net and gives the stability that is needed to plan for the future. But it doesn’t stop there. They also earn an extra sum – the Fairtrade Premium – which farmer groups can then decide democratically how to best use, to improve quality and productivity for their crops and social projects such as education and health services, to benefit their communities.

But farmers can only sell on Fairtrade terms if British shoppers continue to ask for Fairtrade cotton when we buy new outfits. Put simply, more brands using Fairtrade cotton means more money goes back to help women and girls in cotton growing communities.

There seems to be a trend in the UK now to demand to know how clothes were made, but not who grew the cotton that they are made from, and this lack of awareness is resulting in desperate hardship.

It would be good we all posed the question at the store till ‘Who made my clothes?’ That way, transparency in the garment supply chain can extend from the London catwalks all the way back to cotton farmers picking the cotton in Senegal.

Do fashion lovers realise that as many as 100m rural households – 90 percent of them in developing countries – are directly engaged in cotton production? An estimated 350m people work in the cotton sector when family labour, farm labour and workers in connected services such as transportation, ginning, baling and storage are taken into account.

To help increase sales for cotton farmers like Kady, fashion brands can now work with Fairtrade Cotton on two ways – either the finished product is certified as Fairtrade, or using the new Fairtrade Sourcing Program, they can commit to sourcing a certain amount of cotton on Fairtrade terms. Whichever route they choose, their commitment to Fairtrade Cotton means better lives for the farmers who grew your cotton.

Start asking questions when you shop for clothes this International Women’s Day and help women like Kady get a better deal so they can celebrate their achievements.

Watch this short film to learn more about cotton farmers in Senegal

Join Fashion Revolution Day on 24 April 2015. Turn an item of clothing inside-out and ask the brands the question: Who Made My Clothes? #whomademyclothes

Together we will use the power of fashion to inspire change

and reconnect the broken links in the supply chain.

Today Africa is a destination of second hand clothing. Kenya alone imports over 75 million piecess of second hand clothing and distributes not domestically but in the regional market of eastern and central Africa. This is really shameful that Africa in fact produces just over 5.58 % of the total world production of the cotton fiber but only converts 30% into yarn, fabric and apparel for domestic and regional consumption see table below:

Source ICAC

The cotton produced in Africa is spun and woven in Asia, converted into apparels and shipped to USA and EU to be worn for 2-3 years and shipped back into Africa as used clothing to clothe 70% of Africans .

Historical Background:

Cotton, Textile and Apparel sector has witnessed major changes on global policy front over last decade or so, causing major shift in manufacturing and trade patterns. With Multi Fiber Agreement (MFA) being phased out, several countries in Latin America, Europe and Africa lost their share in global trade mainly to Asian countries of China, India, Bangladesh, Vietnam, etc. The LDC and developing countries in affected geographies were the worst hit, where many units closed down as they were no more viable, creating large-scale unemployment. Among these countries were several major cotton producing nations, which started exporting raw fiber without any value addition. Such countries were mainly from Africa – Burkina, Egypt, Zimbabwe, Mali, Nigeria, etc. and Central Asia – Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, etc.

Importance of the textile and apparel sector:

Cotton, Textile and Apparel sector is one of the important sectors in developing countries across the globe, specifically for those, which have been bestowed with Cotton as one of the natural resources. It not only fulfills one of the basic human needs i.e. clothing, but also provides large-scale employment, specifically at the start of value chain (farming and ginning) and towards the end (apparel manufacturing). The figure below depicts the scope of value addition and employment potential across the CTA sector value chain.

The fact that the annual trade Globally in this segment is in excess of US$ 500 billion also provides opportunity to countries to earn valuable foreign exchange.

Steps taken by various countries for sector development:

At present, the countries where manpower is still inexpensive and cotton fiber is abundantly available like China, India, Pakistan, Brazil, Uzbekistan, etc. are focusing significantly to grow the industry. Ambitious schemes specific to this sector are being launched by federal governments in these countries to boost manufacturing for domestic consumption as well as exports. Similar steps are being taken by countries in Africa as well e.g. Government in Sudan has announced a large package for rehabilitation of many of the textile units, Uganda is implementing a special National Textile Policy to increase investments and make units more competitive in the country, Ethiopia has successfully transformed itself into an investor friendly destination for attracting FDI, etc. On similar lines, Nigeria has also earmarked a fund of N100 billion (~ US$ 650 million) for Cotton, Textile and Garment Industries Revival Scheme. One of the most important impacts of this scheme had been the reopening of the United Nigerian Textile Plc factory in Kaduna, which has recalled thousands of laid off workers.

Background: Cotton Cultivation in Kenya

Cotton was introduced in Kenya in the year 1902 by British Colonial administration. In 1953 the Cotton Lint and Seed Marketing Board was established by the government, whose major role was to undertake production, processing and marketing of the cotton sector. At the same time, the Cooperative Unions were also formed to handle primary activities like input supply and payment to the farmers.

At the time of Kenya’s independence (1963) the industry was dominated by private ginners. Over the next ten years, Government provided a lot of support in the form of a well-organised marketing system and timely payments. In addition to this, the Government also invested in a number of textile mills, which supplied to the large apparel manufacturers.

Till 1991, the Cotton Board of Kenya controlled Kenya’s cotton industry. In 1991, the government decided to liberate the sector and allowed private investors to participate. As a result of this, the government support started declining, which ultimately resulted in the decline in cotton production. In recent years, the production has picked up a bit but has been marred by low market demand and lower returns to farmers.

Cotton Production In Kenya ( In MT) ( 1970-2012) DATA source: National Cotton Council, USA

GDP per Capita Income 1960 – 2010

Today, cotton is mainly grown in Arid and Semi-Arid Areas where there are limited economic activities. It is grown mainly by small-scale farmers in Western, Nyanza, Central, Rift Valley, Eastern and Coast provinces of Kenya. An estimated 200,000 farmers grow most of the cotton on holdings of less than one hectare. Majority of the production takes place in the Eastern zone comprising Coastal, Eastern and North Eastern regions. These regions contribute to ~85% of the production. While the Western zone, comprising Nyanza, Rift Valley and other western regions, contribute to about 15% of the seed cotton production. In Eastern Kenya, the cotton crop is sowed in the month of October whereas in Western regions it is sowed in March.

Necessity for a sector development plan and its key components:

Earmarking a fund for the sector is the foremost step required to be taken by government having sincere plans for revitalization of the sector. Beyond that comes the requirement of a broad vision for the sector, a set of guiding principles to make best use of those funds. While rehabilitating the units may be important where maximum funds need to be committed, but in order to achieve sustainable growth it is important to address the other issues also, to help industry to go that extra mile. This is specifically true for CTA sector where any unit’s viability is a function of several interlinked parameters of raw material, manufacturing and marketing; hence the desired way is to take a holistic view rather than a stopgap arrangement.

The requirement is of developing a comprehensive sector strategy, which addresses the various issues in the sector in most efficient manner. The issues can be high power cost, lack of marketing linkages, low technology level, lack of skilled workforce, absence of incentives to attract FDI, lack of support infrastructure, protection of domestic industry, export incentives, raw material allocation, weak supply chain linkages, etc.

The development of such a strategy will require:

- Mapping of the current status of sector

- Identification of key gaps

- Benchmarking against global leaders

- Developing interventions to address the issues holistically

- Preparing a roadmap for its implementation

How ACTIF can help?

The African Cotton and Textile Industries Federation (ACTIF) is a not for profit regional industry/trade body formed in June 2005 by the Cotton, Textile and Apparel sectors from Eastern and Southern Africa covering the COMESA, SADC and the EAC trading blocks, and currently includes members of National Associations from 25 countries (Botswana, Burundi, Cameroon, Cote d’Ivoire , Egypt, Ethiopia, Kenya, Lesotho, Ghana, Madagascar, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, Sudan, Mauritius, Malawi, Madagascar, Mozambique ,South Africa, Swaziland, Serra Leone , Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe).

ACTIF’s milestone achievements include

- MOUs with COMESA and with the East African Community for trade development along the Cotton, Textile & Apparel (CTA) value chain

- Key contributor to the COMESA CTA strategy and now officially recognized as an implementing partner of the strategy

- Participated in EPA negotiations and developed draft RoO for apparel exports to EU under EPA

- Successful developed a common position white paper for our 20 member countries on AGOA

- Currently engaged in an advocacy project towards the sustainability of AGOA in East Africa and also to our other member countries supported by TMEA.

With the funding support of Center for Development of Enterprise (CDE), ACTIF has recently conducted a CTA sector supply side analysis of four countries in Eastern Africa – Kenya, Sudan, Tanzania and Uganda. This comprehensive study is on the similar lines what needs to be done in Nigeria as well.

With the mandate to pursue development of textile sector in Africa, liaison with international donor partners, network with international consultants and experience of doing similar strategy work, ACTIF is well suited to assist Bank of Industry, Nigeria for development of CTA Sector Strategy for Nigeria.

Given the mandate, ACTIF along with partner international and local consultants would start with conducting a comprehensive mapping of Nigeria textile sector. This step would be followed by a fact-based analysis along with benchmarking with global best practices. The ultimate outcome of this exercise will be:

- An As-is analysis of Nigerian textile industry

- Key risks and mitigation strategy

- Identification of opportunities in the sector

- Interventions for sector growth

- Implementation road map

When Charles Oboth was first asked to reopen the derelict cotton ginnery in Gulu, Northern Uganda, his response was a simple and strong ‘no’. The compound was overgrown with grass taller than him; the ginning machines were fifty years old and dilapidated. Gulu had been at the centre of a war for two decades and for Charles and his fellow Ugandan colleagues it was considered a no-mans-land. But the owner was persuasive and visionary, and eventually Charles gave in.

That was 2009, and just five years later the ginnery is unrecognizable. With Charles as General Manager, it has grown rapidly to be one of the largest ginners in Uganda, employing 350 people at peak season and buying conventional and organic cotton from 40,000 farmers. Many of these cotton farmers returned to their small farms from Internally Displaced People’s camps in 2008 and have had to rebuild their homes and lives from scratch. Collaborating with other ginneries in the North, the Gulu ginnery has supported the farmers with vital tools, access to a market, and free training in organic practices that increase their yields and sustain the health of their farms. 2,000 of the farmers are Organic and Fair Trade certified, so they receive an additional income per kg above the local price. Meanwhile ginnery employees are paid a fair wage and provided with free meals, uniform, access to healthcare and support to form workers groups. The ginnery has reintroduced entrepreneurialism and economic opportunity in a setting that saw most of the local economy wiped out by the war.

Challenges persist of course – Gulu is not an easy place to do business. The most basic infrastructure is still lacking: roads can get washed away in the rainy season, electricity is forever patchy, and it can take a full day for an engineer to come from Kampala to fix the generator if it breaks.

But the Gulu ginnery is an example of the power of the fashion industry when it is done right. Fair trade cotton ginned in Gulu travels onwards to Japan, where it becomes t-shirts and dresses sold to conscious consumers. In order to do more good, the ginnery needs new Fair Trade buyers. Natalie Grillon, an employee at the ginnery for the last two seasons, has established an enterprise called ‘JUST’ that supports buyers and designers to source ethically made materials, including cotton from Gulu. That means more demand for the ginnery to meet and so more support, training and money for farmers.

But the Gulu ginnery is an example of the power of the fashion industry when it is done right. Fair trade cotton ginned in Gulu travels onwards to Japan, where it becomes t-shirts and dresses sold to conscious consumers. In order to do more good, the ginnery needs new Fair Trade buyers. Natalie Grillon, an employee at the ginnery for the last two seasons, has established an enterprise called ‘JUST’ that supports buyers and designers to source ethically made materials, including cotton from Gulu. That means more demand for the ginnery to meet and so more support, training and money for farmers.

Charles and his Ugandan colleagues have built the ginnery’s success with sweat and tears. They sacrifice evenings and weekends throughout the season; they even offload cotton on Christmas Day. Nobody says it is easy. But up in the blossoming cotton fields of Northern Uganda, we can start to see what a Fashion Revolution really looks like.

By Tamsin Chislett – proud to be a previous employee of Gulu’s cotton ginnery.