What the lives of garment workers can teach multi-national brands and their customers

Fatima, Sokhaeng, and Usha are all garment workers making clothes for multi-national brands in factories across South and Southeast Asia. Fatima lives and works in Dhaka, Sokhaeng in Phnom Penh, and Usha in Bangalore. Their work is similar—cutting and sewing garments for eight or more hours per day, but their lives and the lives of their compatriots also vary in important ways. What can the lives of these women teach multi-national brands and their customers about how to create and maintain sustainable supply-chains, where people who make the clothes that the world wears are treated with respect and do more than just survive? In other words, how can brands, with the support of consumers, win the “race to the top” where all do well, rather than the proverbial “race to the bottom” where brands compete by getting as much out of their workers for as little as possible?

Fatima, Sokhaeng, and Usha are three of 540 women that Microfinance Opportunities has been tracking for the last eight months or so. We have been asking them about how they earn and spend their money, their daily schedules, whether they are happy, in pain, or suffered an injury, the conditions in their workplace, and any special events that happened in their lives. From this information we have been able to weave together the individual stories of the workers, as well as generate an aggregate picture of the lives of the women who make our clothes. You can find accounts of these stories here for Bangladesh, Cambodia, and India.

Fatima and others like her who are participating in the Garment Worker Diaries in Bangladesh often worked over 60 hours a week in the latter part of 2016 during the first few months of the study. In contrast, Usha and the other workers in Bangalore invariably worked 48 hours a week or less—still a lot but far less than the women in Bangladesh. The women in Cambodia fell somewhere in between—48- to 60-hour weeks were the most common in Cambodia. Furthermore, in both Bangladesh and Cambodia, the number of hours the women worked per week varied far more than they did in India, where the women consistently reported 48-hour weeks.

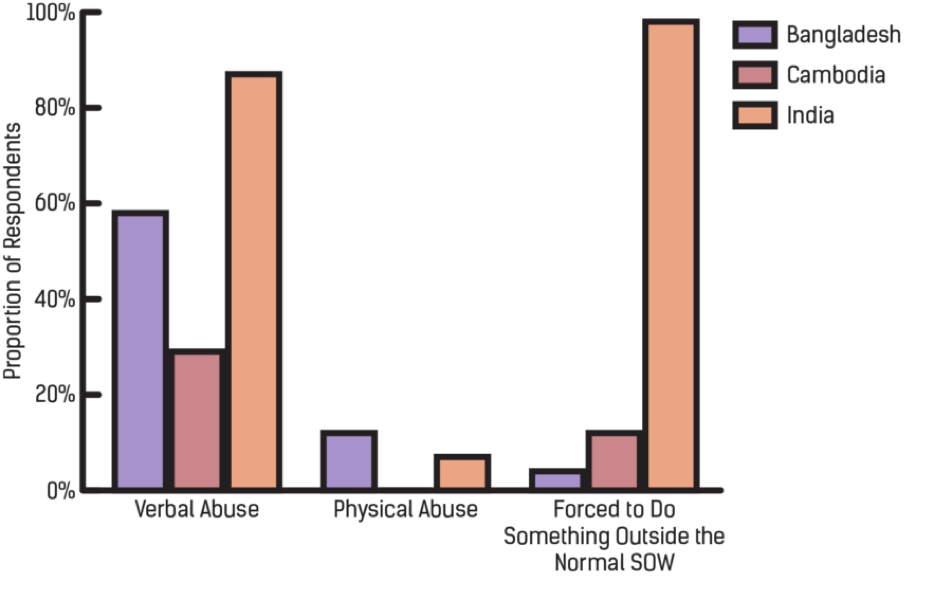

Figure 1: Hours Worked per Week

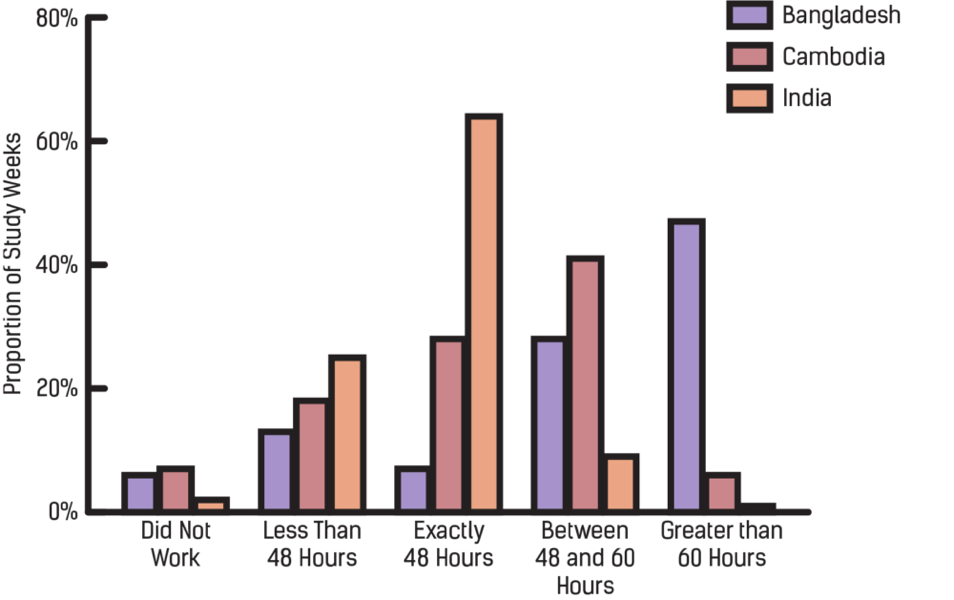

From the reports of how many hours they worked and how they varied from week to week, it looks like the women in India are the best off. But this is not altogether the case. Usha and her Indian counterparts reported far higher levels of verbal abuse in the workplace than did the women in Dhaka or Phnom Penh. And women in India consistently reported being forced to do more work than their allotted quota for the day. Meanwhile, women in Cambodia had the fewest reports of verbal abuse and no reports of physical abuse.

Figure 2: Reports of Abuse at Work

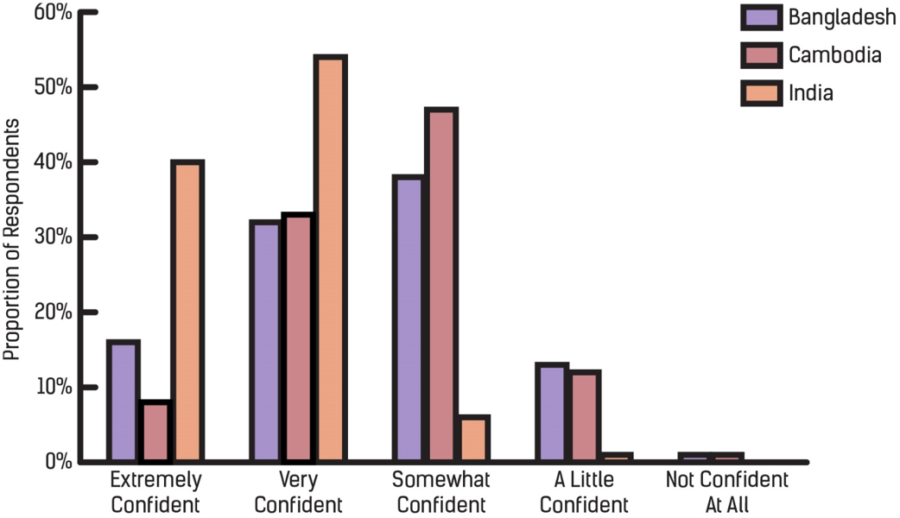

Further complicating the picture, women in Bangladesh and Cambodia participating in the Diaries study reported having mixed levels of confidence in whether they would be able to use the emergency exits in their workplaces in case of an emergency—almost 40 percent of Bangladeshi and 50 percent of Cambodian workers were only somewhat confident, while the Indian women reported the most confidence—over 90 percent reported they were extremely or very confident.

Figure 3: Confidence in Use of Emergency Exits

There may, of course, be differences across the countries in how the women perceive their situation, but even taking this possibility into account the differences across countries are so great that it is hard to fathom that they are simply due to differences in perception. What these findings suggest is that just because a set of factories in one country have worse conditions than factories in another country on one dimension does not mean that they have the worse conditions on all dimensions. So why can’t factories in Bangladesh and Cambodia and the brands that hire them have their workers work reasonable hours? Why can’t Indian factories stop the verbal abuse their workers suffer? Why can’t the Bangladeshi and Cambodian factories ensure that their workers can use designated exits in an emergency?

From a human rights perspective we can simply argue that the factories and the brands that hire them should stop treating their workers badly and adhere to some basic standards—higher than the best experiences of the women in our study. But these findings suggest that even by the lower standards of “business necessity” there is no justification for the behavior of the factory managers and the brands that hire them: other factories are able to treat their workers better in certain ways and stay in business, so why shouldn’t all factories be able to do so? In other words, there is no excuse for the treatment of the workers that the Diaries data are revealing, even by the lower standard of “we have to treat our workers this way just to stay in business.” It is time that the brands send this message loud and clear to factory managers, and that consumers ask the same of the brands. This way, maybe we can see the beginnings of a “race to the top.”

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Garment workers in Phnom Penh often live in housing blocks like the ones seen here—single rooms in dystopian looking concrete buildings. While the homes often have electricity and private bathrooms, there are many in less-developed areas of the city like these, which are located next to an informal trash dump. On average, a room in one of these buildings will cost 120,000 riels per month, equal to about $30.

Workers leave their homes early in the morning to walk to their factories. The factories vary in size and formality but they are often in walled compounds with large metal gates. Conditions in factories have improved over the years but many of our respondents report that they are concerned for their safety for various reasons.

Workers typically get a quick break for lunch and crowds of women will surround vendors like this one, snatching up her prepared lunch fare for a few thousand riels. Workers will also sometimes buy prepared breakfasts and dinners from vendors too.

After their shifts, which can last anywhere from eight to 12 hours, garment workers leave their factories and walk home. The women in the photo wear hats and long sleeves shirts to protect themselves for the sun. Some wear scarves or facemasks, which they use to try to limit dust and chemical smells they breathe in while working.

The women in our study will often purchase food for dinner on the way home from the factory. They do this almost every day—food will spoil if kept too long and most homes do not have refrigerators. The markets of Phnom Penh are loaded with fish, snails, chicken, and beef as well as fruits and vegetables. While many respondents cook using gas stoves, fish is best cooked over coals.

Long days at the factory followed by chores around the home tire our garment workers. The women in our study like to relax at the end of the day, if they have the time, and many enjoy watching television. However, many cannot watch for much longer than an hour—they have to sleep so that they are rested for another day of sewing clothes destined for Western markets.

Kampong Speu, Cambodia

Most garment factories in Cambodia are in Phnom Penh but they are also located in other provinces of Cambodia, including Kampong Speu. Life here is much different from life in Phnom Penh. Homes here are larger and similar in style to the home above.

Garment work is an important source of employment for young women living in this area but households often engage in other livelihoods too. For example, many households engage in some type of agriculture.

Buddhism is the national religion of Cambodia and evidence of its influence is visible throughout the country. One key example—many communities have a Buddhist temple similar to this one. It is a place for meditation and learning. Our respondents in Kampong Speu sometimes bring offerings to temples during religious holidays.

Religious and traditional beliefs are prevalent in this area. Figures, like the one shown here, guard homes from evil spirits. People hope that the figures will keep things like illnesses or curses into the home.

Bangalore, India

Our respondents in Bangalore live in a variety of types of homes. Some live in in single-family, detached homes like those in this community near the town of Mandya.

Others live in apartment buildings of various shapes and size. These apartments are located near the town of Bidadi, less than an hour away from Bangalore by car. The unpaved roads and construction show that this area is still developing.

Regardless of where respondents live, they are all bound by a schedule set by the factories. Each morning, the garment workers wake-up early to prepare themselves and their families for the day. They will often take a factory-sponsored transport to their jobs where they will work for eight hours.

After their shifts, the women stream out of their factories and board transports headed back to their homes. Some work conditions here are better than in the other countries we are studying, but the women in our sample report that their supervisors yell at them frequently.

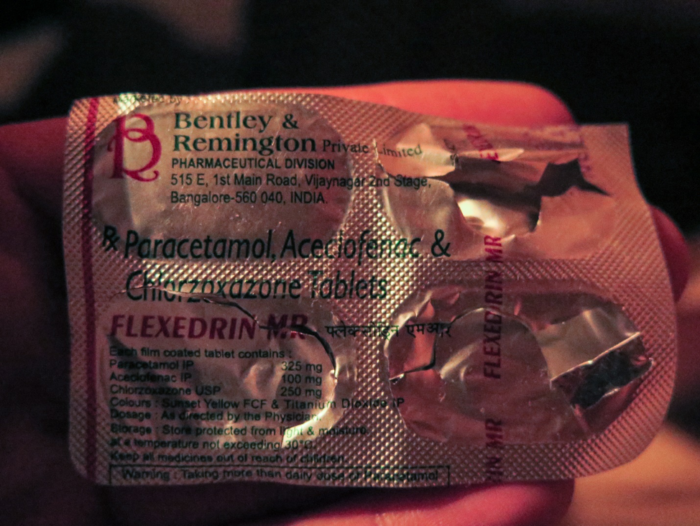

While the workers here often have shorter days than those in Bangladesh and Cambodia, the repetitive nature of their tasks takes its toll. Many workers complain of pain in the arms, back, and legs. One worker we visited had gone to the clinic and a doctor prescribed these painkillers.

The women in our sample often do not get much leisure time—they have to cook and clean for their families and care for their children. In this photo, the daughter of one of our respondents studies. Outside the frame, her mother is keeping a watchful eye even as she conducts an interview with one of our enumerators.

Many of the respondents in our sample are Hindu and devout followers often have some kind of shrine in their homes. Images of gods, oil candles, and decorative flowers are common. At the end of a long day, some workers will say a quick prayer before beginning their routine again the next day.

Phann is a 40-year-old garment worker living in Phnom Penh with her husband, a security guard. Their rented room is typical for a garment worker—encased by concrete walls and covered by a tin roof with one bathroom and no kitchen. Since Microfinance Opportunities (MFO) began interviewing her in July, Phann has reported working long hours, making products for major clothing brands. She has worked 61 hours a week on average, including three weeks when she worked more than 70 hours, well above the 60-hour week maximum mandated by Cambodian law. Despite her illegal hours, she is paid 66 cents an hour according to our data, falling just short of the legal minimum wage of 67 cents per hour.

Phann, like the other 180 women participating in MFO’s Garment Worker Diaries in Cambodia, is hoping that 2017 will bring new money as the Government of Cambodia has mandated that factory owners increase the minimum wage from 67 cents to 73 cents per hour, equivalent to an increase from $140 to $153 per month [1].

Most of our diarists are positioned to receive that increase—approximately 68 percent report earning the minimum wage, if not higher. The other 32 percent of workers stand to be disappointed, according to a preliminary analysis of the data. They earn only 57 cents an hour on average, so far below the minimum wage that an almost 30 percent increase in their wages is unlikely.

Not only are they receiving less than the minimum wage, but the ways in which their earnings are calculated are often opaque, and their payment schedules are inconsistent. For instance, Mao—a 28-year-old garment worker living in Phnom Penh—received checks showing that she earned the minimum wage. During our first interview, she reported that the factory paid her $140, but she could not tell us how many hours she worked during the pay period. At that moment, we were hopeful she would be one of the garment workers who received fair wages for her work. Her next check was for $137.50, but she worked 250 hours during the pay period which equates to only 55 cents an hour. She fared better on her next paycheck, earning 68 cents an hour for 227 hours of work. However, by the time she received her fourth check, any pretense that she was receiving fair wages had disappeared. She earned $90 for 200 hours of labor, equal to 45 cents an hour.

At least Mao’s employer paid her. Chen, who works in another factory in Phnom Penh, worked 194 hours but was never paid as her employer absconded. She and her colleagues did everything possible to stop him: they attempted to block the exits to the factory to prevent his escape and sought a court order to detain him, or at least seize the assets of the factory, but those efforts proved unsuccessful. As of this writing, she has still not received any compensation for her work.

For women like Mao and Chen, and women like Phann who are paid fairly but work in excess of what is allowed by law, an increase in the minimum wage will not be enough to ensure their dignity. Brands and the Government of Cambodia must enforce the regulations that ensure fair wages and working conditions.

There has been slow progress in this regard, and a lack of transparency in the supply-chain makes evaluating the pace of progress difficult. Organizations like the Solidarity Center and Human Rights Watch are investigating working conditions to bring better transparency to the sector, but their main leverage point is to indict the reputation of the brands, a real but indirect threat to brands’ bottom lines. Consumers, with their ability to directly impact brands’ by altering their purchasing patterns, are the ultimate leverage point. For change to occur, you as consumers must demand transparency and fairness throughout the supply-chain.

To ensure dignity for these women, you must demand a fashion revolution.

[1] The legal minimum wage in Cambodia is $140 per month and is not typically reported as an hourly rate. The legal regular work week, before earning overtime, is 48 hours per week. For an average month, this equates to 67 cents per hour. The government has set the minimum wage in 2017 at $153, equal to 73 cents per hour.

The Garment Worker Diaries is a yearlong research project, led by MFO and supported by C&A Foundation, which is collecting data on the lives of garment workers in Bangladesh, Cambodia, and India. Fashion Revolution will use the findings from this project to advocate for changes in consumer and corporate behavior and policy changes that improve the living and working conditions of garment workers everywhere.

By Allison Griffin for Remake

Few things are more powerful than a room full of women who have something to say.

As part of our Remake Journey we traveled 2 hours outside of Phnom Penh along dirt roads to a small school in the middle of rice fields, one of the few safe places makers are able to unite to talk about their rights without the police breaking up the meeting.

This gathering was hosted by Solidarity Center, to help makers fight for their rights. We learned that when big factories agree to cheap prices and tight deadlines, they often can’t meet these demands. So they ship orders off to fly by night operations–dark, dingy subcontracted factories where the conditions are the worst.

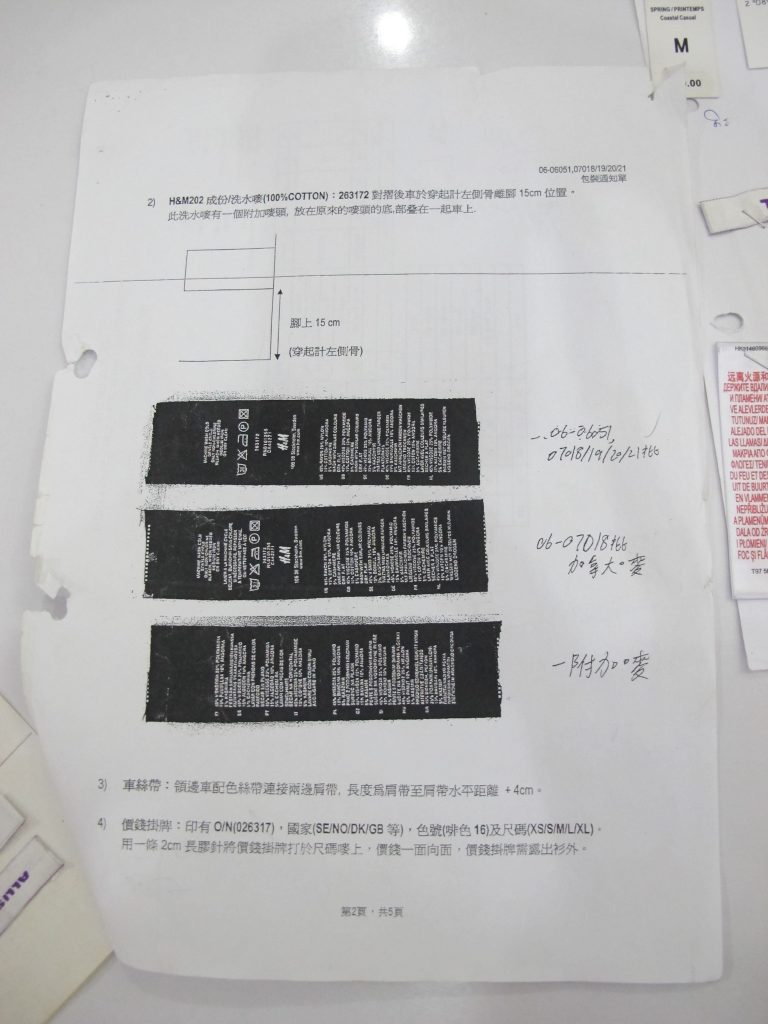

The women we met had sneaked out labels from the brands they illegally sew for including Zara, H&M and Tommy Hilfiger. It was dangerous for them to sneak these photos and labels out but they did it anyway, in the hope that we and you as readers would help them, to ask these brands pressing questions about why they worked such long hours for so little.

I had the honor of sitting down with one such maker, Char Wong. This is her story:

I grew up in a family of eight children raised by a single mother. I was a farmer before working in a subcontracted garment factory. I found work in a subcontracting factory to earn more money and provide a better life for my own family, but the pressure from the daily quotas is stressful and the money is not enough.

I support my 16-year-old son, 10-year-old daughter, my elderly mother, along with my husband who is a farmer. I struggle to feed everyone with the minimum wage and extra $2.50 a day that I earn. My mother has diabetes and her medicine costs $30 a month, over 20 percent of my monthly income. I also want to save money for my children’s education.

wanted a better life for myself and my family which is why I took this work. But life has become harder. I get paid per 12 pieces, but if there’s even one single error in the batch, I don’t get paid at all.

A few years ago, the factory would receive an order for a new design every two or three months, but with the new fast fashion cycles, it now gets more and more new designs in a shorter amount of time. Learning complex designs is very difficult and we get no training. Sometimes it takes two or three hours just to learn and the factory supervisor scolds us for any mistakes. The more time it takes to learn a design, the less time I have to meet the quota and the less money I make. I typically make $5 a day, but with the more complex designs, I only make $2 a day.

Sometimes I cry because I fear I won’t meet the quota and get paid.

Like most parents from all corners of the world, I want a better future for my two children. I hope to pay for their college education so that they can work in Cambodia’s government. Government jobs pay well and do not require hard physical labor. I hope that my children can be government leaders and help improve the conditions and rights of future garment factory makers, just like myself.

I am grateful for organizations like the Solidarity Center, who teach us about our rights. I am learning to speak up more. I want my story and my colleagues’ stories to spread to people throughout the world.

You being here, listening, makes me hopeful.

I definitely felt a lot of girl power throughout the day, both from our own all female crew and the makers we met. These women are not playing victims, but fighting for their rights and educating themselves on their rights. Speaking with Char Wong, I realized that the hopes she has are fundamentally no different from mine–for a fulfilling life. I hope as a designer, I can be a part of the change and that this story moves you to buy better. Together we can #remakeourworld.

By Allison Griffin for Remake

I am not nervous to speak with you at all. My life has been full of hardships. At this point I am not scared of anything.

We met Sreyneang, a woman who has been working inside a Cambodian denim factory for three years, but has worked in the garment industry for many years. We traveled back to her home with her after her shift in a vehicle similar to a tuk tuk, but larger and less put together. The motorbike pulled a wagon with wooden beams across as seats and you had to balance the weight of people sitting, so that it would not tip over.This or trucks with empty backs are what most of the makers in Cambodia take to and from the factory.

I’ve been sewing since I was 15, my whole life. My husband was a security guard but he got sick. So now my garment maker salary supports him and my two daughters.

I work two jobs. I get up early. Take my kids to school. Then I take transport to the factory. At night I work as a tailor to supplement my income. I usually work until 10 or 11PM at night.

My home village is 3 hours away but I have a small house I bought here, which is unusual because most of my colleagues in the factory are stuck renting from landlords who raise the rent every time our wages are raised.

Her home was at the end of a dirt road and there were a lot of children all around. It was one room with earth flooring and a woven mat and benches, but no beds or indoor plumbing, but it did have electricity. She said she saved up to buy this land and built this house because it was closer to work.

My daughter told me she would drop out of school and start working to help me because she knows how stressed I am. But I said NO. She’s 14. I want her to stay in school and have a different life than me. I want my daughter to go to a school like Parsons and become a designer!

At dinner, she bought water bottles for all of us, which was very kind because they are expensive. While eating dinner, Sreyneang said she usually has only two spoonfuls of rice for dinner. It definitely put things into perspective and you could see the direct effects of low wages.

Sreyneang said she felt blessed that she met us. She wondered if her life would change from this meeting. We parted ways with WhatsApp numbers, big hugs and promises for a future evening together.

The world is round and we are all sisters. I want designers to know of the hardships and suffering in my life, of makers’ lives and the low wages we get.

Fashion design schools have an allure. Many young women in their early twenties get fashion degrees hoping to launch their own lines and drive the aesthetic of a camera-ready $3 trillion industry.

In reality, they enter a competitive market, applying for entry-level design positions in expensive cities. If accepted, they will work long days, under tight deadlines and fluorescent lights, all for salaries as low as $30,000. These graduating designers have little choice but to dive in and hope for a better future.

Interestingly enough, overseas, where roughly 97% of our clothes are made today, there are also young women in their early twenties toiling away on the assembly line. Their wages are low, working hours long, and conditions often difficult. And yet, for these young makers, factory jobs also represent hope for a better future.

Today we buy more clothes and yet somehow pay less for them. This phenomena called fast fashion, much like fast food means the industry cuts corners. What started as a way for more of us to look good on a budget has resulted in a rise in cheap, chemical filled clothes, brought to us by human hands forced to work longer hours for low wages.

But this article isn’t about shaming the fashion industry for building a broken business model. It’s about linking the amazing women on either end of the supply chain – designer and maker – to come face to face, woman to woman, to create a more human centered fashion industry.

80% of the people who are making our clothes are women, usually just 18-24 years old. Their hopes and dreams match ours: to be happy, healthy and see the world. At Remake, we pass the mic back to the women hidden at the other end of the supply chain. We have traveled to Haiti, India, Pakistan and China, to ask her to share her stories.

Our recent Remake Journey to Cambodia was in partnership with Levi Strauss Foundation and Parsons School of Fashion, home to fashion icons such as Donna Karan, Alexander Wang and Tom Ford. We took three of Parsons’ amazing graduating designers:

“As a fashion designer, we are so distant. A lot of our industry uses makers oversees and are so disconnected from them, but these are the people who are creating our work and our designs. So meeting with them and having that more manifested in our heads is a connection we need to be thinking about more.”

Meet Allie Griffin, whose great grandmother used to make our clothes right in NYC’s old garment district. Coming to a prestigious school like Parsons and recently interning at Oscar de la Renta, she feels that in one generation her family has come full circle from maker to designer.

“Fashion effects economies, politics…something you don’t normally think about. But at the end of the day there are people making our clothes, human lives depend on these jobs. That’s why fashion is important to me.”

Meet Anh Le, who designs menswear and has recently interned at American label Thom Browne. Her parents came as refugees from Vietnam, where her family worked in the garment industry. As an Asian aspiring designer, she wants to do right by creating clothes that are ethical and respect the maker.

“I’m really interested in being part of this new generation of fashion designers. We are interested in finding ethical and sustainable ways to participate in fashion. There are a lot of problems that I see, like low wages, underage workers, poor working conditions. I know a lot of my fellow students and I think it’s time to change how we make fashion.”

Meet Casey, who has designed future forward collections in collaboration with Tide and Intel. She is deeply interested in creating more sustainable patterns and textiles in union with factory systems.

Day 1: Tonlé: Zero-Waste Fashion

We visited Cambodia’s first zero-waste brand Tonlé to experience the power of fashion as a force for good. Tonlé provides at-risk women with a living wage, health care and good working hours, while also being good for our planet.

“From the moment we stepped inside the gate you could feel it, it was such a special place. There were a group of women at tables in the front yard knitting together, and they welcomed us warmly with smiles,” recounted Casey. “I spoke with Ny, a transgender male who is in charge of stock and shipping.”

“I think about how the clothes we make go all over the world. I also think that the people who buy from Tonlé really care about us, the people who make them. Most of the makers in the clothing industry come from really poor places, and they work so hard to try to achieve better lives. I want there are more brands like ours so that there are more people who have jobs as good as mine.” – Ny

Day 2: 2,000 People Making Our Jeans

We traveled down a winding bumpy and dusty road to a denim factory on the outskirts of Phnom Penh where jeans are made for every imaginable brand: from JCPenney and Kohl’s to Simply Vera by Vera Wang and J Lo.

Walking down the assembly line, you see hundreds upon hundreds of women, heads down doing fast repetitive motions, backs crunched just like ours over laptops. The sheer volume of stuff, and noise from the machines was overwhelming. All in our quest for cheap jeans.

The denim distressing unit was especially eye-opening.

“All the cuts, wear marks and washes are done by human hands, and these tasks are clearly physically demanding and even dangerous, from all the spraying of harsh chemicals. As soon as our tour ended my brain was overwhelmed with what I had just seen; how could one pair of jeans sell for $20 and have had so many hands work to produce them; the math behind where the money goes does not scream fair at all.” – Casey

That evening one of the denim makers invited us to her home for dinner in a nearby slum. We traveled in the open air truck with her, where passengers need to balance sitting on both ends to ensure the truck did not topple over. Makers in Cambodia have lost their lives in trucks just like this one, which thousands use to get to work everyday.

“I started working when I was 15. Since then I’ve worked at several different factories. My husband is sick, so my $140 a month salary support’s my whole family. I work at the factory all day and then work a second job as a tailor at night. I want my daughters to learn English and go to a school like Parsons. I’ve actually seen New York on TV and maybe someday I can come visit. I want young designers to know about my life. I have suffered but I feel stronger having met my sisters from NYC.” – Sreyneang

Sreyneang’s home was no bigger than two dining tables pulled together, the floor just dirt and the roof sheet metal. Her husband, children and neighbors all crowded in to meet us. Her home may have been small but her heart was huge. When we sat down to eat together, she kept offering us bottled water she had bought for us and took only two spoonfuls of rice. Insisting that we, her neighbors and even the stray dog and cat that stopped by had something to eat first.

“A truly inspiring, loving, and kind soul, I haven’t stopped thinking about her and I don’t think I ever will.” – Casey

Day 3: Sub-Contracted Factories, The Most Invisible People

Few things are more powerful than a room full of women who have something to say. We traveled 2 hours outside of Phnom Penh along dirt roads to a small school in the middle of rice fields, one of the few safe places makers are able to unite to talk about their rights without the police breaking up the meeting.

This gathering was hosted by Solidarity Center, to help makers fight for their rights. We learned that when big factories agree to cheap prices and tight deadlines, they often can’t meet these demands. So they ship orders off to fly by night operations–dark, dingy subcontracted factories where the conditions are the worst.

The women we met had sneaked out labels from the brands they illegally sew for including Zara, H&M and Tommy Hilfiger. It was dangerous for them to sneak these photos and labels out but they did it anyway, in the hope that we and you as readers would help them, to ask these brands pressing questions about why they worked such long hours for so little.

Some of these women made less than a $100 a month despite working all day long. Others noted that they were forced to take pregnancy tests and if it was positive, they were fired.

We learned that some factories pop-up during holiday rushes, then shut down to avoid paying the makers anything once the order is filled. Some of these women had been sleeping outside factories to get their back wages to afford food and rent. One of Solidarity Center’s incredible staff leaders Somalay, said to us,

“We will never stop. We will fight.”

She cares and risks her life, because she’s been there, she used to be a garment maker herself.

“I wanted a better life for myself and my family so I took this work at a subcontracted factory. But life has become harder. I get paid per 12 pieces, but if there’s even one single error in the batch, I don’t get paid at all. I used to make a new design every 2-3 months. Now, it’s two to three new designs per month. The designs are more complicated but we get no training. It’s harder to meet the quota. Sometimes I cry because I fear I won’t meet the quota and get paid. I hope you will help me and my colleagues by spreading our stories to the world. You being here, listening, makes me hopeful.” – Wong Char

“I definitely felt a lot of girl power throughout the day, both from our own all female crew and the makers we met. These women are not playing victims, but fighting for their rights and educating themselves on their rights. Some of the makers dressed up in professional attire, including blazers and heels and every person had a pen and paper they were furiously taking notes with. Speaking with Wong Char, I realized that the hopes she has are fundamentally no different from mine–for a fulfilling life.” – Allie

Journey #5 ended with see-you-laters, not goodbyes. Our designers and makers became friends on Facebook WhatsApp and promised as sisters to keep in touch and fight together to make fashion a force for good.

It takes 100 pairs of hands to bring each of our clothes to life. Next time you go shopping, we hope you think of Ny, Sreyneang and Wong Char and their dedication to our fashion.

We hope you join our movement and buy better from brands like Tonlé. Together we can #remakeourworld

Authors: Conor Gallagher and Guy Stuart, Microfinance Opportunities

Four years ago today, a fire at the Tazreen Fashions factory outside Dhaka killed 112 garment workers and injured nearly twice as many. In its aftermath, there was an international outcry calling for greater regulation of health and safety conditions in garment factories across the country. Clothing brands and retailers came together and agreed to better monitor conditions inside the garment factories where their clothes are made; and then, after the Rana Plaza disaster, the Bangladeshi government adopted new legislation to strengthen its regulatory body in conducting safety inspections. As of March 2016, the Department of Inspection for Factories and Establishments had inspected 1,549 ready-made garment factories across the country.[1] Despite these steps, workers in garment factories continue to face poor health and safety conditions not only in Bangladesh but in other major garment exporting countries as well. These poor conditions do not necessarily result in major tragedies such as those at the Tazreen Fashions factory or Rana Plaza, but they nevertheless expose the workers in the factories to unsafe conditions and cause them undue pain and suffering.

Through the Garment Worker Diaries project, research teams in Bangladesh, Cambodia, and India have been collecting weekly data on what garment workers earn and buy each week, how they spend their time each day, and whether they experience any harassment, injuries, or other significant events while at the factories. Though we are still in the early stages of data collection, our project covers 540 workers from across these three countries, and we are hearing from them about the health and safety hazards they face.

Workers in our study have informed us about major events that have taken place in the factories. In Bangladesh, women from two different factories have reported fires. In the first case, a fire broke out during their lunch-break, and workers had to put it out themselves. In the second instance, a fire broke out during a midnight shift and took an hour to be extinguished. No casualties were reported in either case.

In Cambodia, one worker informed us that her factory’s owner had not paid their salary, so she ended up going to stand guard at the factory to try and force him to pay. She then filed a complaint in court against the owner in the following week, again asking him to pay. This was more than two months ago, and the situation has still not been resolved. We have seen similar incidents in Bangladesh. For example, six workers from a factory near Dhaka reported a factory-wide strike as the owner had not paid their salaries on time. This resulted in altercations with police officers, pressuring the owner to pay shortly after the fights broke out.

Not all issues that workers face are major events like fires or strikes; workers have been telling us about some more frequent and persistent challenges they deal with too. Workers in our study have reported on repeated harassment in the work place. These incidents range from being yelled at or insulted to sexual harassment. In Cambodia, workers have been willing to share with us the insults they receive. Some examples include women being called “idiots” or “crazy girls,” while one woman’s supervisor told her that she had “no bright future with [her] careless working style.”

Finally, the workers in our study tell us about the pain they endure because of their work. In India and Cambodia, for example, we have found that workers regularly report instances of chronic pain. Respondents in these countries have common ailments: for India, workers commonly experienced back pain. In Cambodia, workers most commonly have reported suffering from headaches. These types of pain are common among garment factory workers who face uncomfortable working conditions that require them to stand in hunched positions performing repetitive tasks for hours on end. Eventually, these conditions wreak havoc on the workers’ bodies, causing the types of chronic pain that our respondents regularly report. In three extreme cases, workers from India reported experiencing back pain every week, and they have reported that this pain can last anywhere from one hour to several days.

We are still in the early stages of collecting and analyzing the data from the 540 women participating in our study. As the Garment Worker Diaries progresses, we will continue to collect information on what is going on inside garment factories in Bangladesh, Cambodia, and India. We will use interviews and surveys to delve deeper into the specific working conditions that workers face.

We now ask you: what would you like to know about the women who make our clothes and the conditions they face at work?

Tell us by tagging us at @fash_rev #workerdiaries

The Garment Worker Diaries is a yearlong research project led by Microfinance Opportunities in collaboration with Fashion Revolution and with support from C&A Foundation. We are collecting data on the lives of garment workers in Bangladesh, Cambodia, and India. Fashion Revolution will use the findings from this project to advocate for changes in consumer and corporate behavior and for policy changes that improve the living and working conditions of garment workers everywhere.

[1] http://database.dife.gov.bd/

Header photo credit: IndustriALL Global Union

Channa needs to spend over 300USD per month on food to feed her four children, chronically ill elder sister, husband and herself. Photo by Sok Chanrado

I’ve lived in Phnom Penh since 1992. My hometown is in Prey Veng Province. Where I used to live in the countryside, it would flood every year. I couldn’t find food to eat and I was an orphan. I moved to Phnom Penh to live with my sister so that I could work at a factory to feed myself. Phnom Penh had and still does have many more job opportunities than my hometown. I like living here for that reason.

The things I value most in life are having enough food to eat, and living together with my children and husband. I want to be able to send my kids to school everyday but financially I can’t. Simply speaking, when you don’t have money you cannot do anything. If I want my kids to go to school I have to look after my younger daughters, but then I can’t go to work.

My husband is a construction worker. Both of our wages combined are not enough to live off of. Plus, I have another mouth to feed – my elder sister. When her health is good, she will help out by taking care of my younger kids. If she doesn’t feel well, my elder sons must take care of their sisters and cannot go to school.

Despite our best efforts, things haven’t worked out the way we wanted. For example, in 2012, when my youngest daughter was born I couldn’t work and I didn’t have anything to eat. I had a big fight with my husband. It’s normal for a couple that lives together to argue often. After our fight one of my friends asked me to move to the border of Cambodia near Thailand but I didn’t go. I decided to go to an orphanage to ask for a place to stay instead. They did not let us stay. I didn’t know what to do, so I sold all of my stuff from living in Phnom Penh. If you can’t work you can’t live. I thought if we were in the provinces people would help us out so we moved to Sompov Loun for about five or six months. But then my kids became allergic to the land there. I didn’t know what to do. I asked another orphanage to let my kids learn at their school but my kids weren’t accepted because they weren’t orphans.

In my opinion, if your kids are educated they will think about and respect you as a mother. I have seen kids on my block beat their moms, cursing them. Kids nowadays have no manners or respect whatsoever. I hope and believe my kids, whether they are educated or not, will think about me as a mother and I can depend on them in the future. If they are educated though, I believe I can depend on them more. My 14 year-old son is a good kid. He does house chores, looks after his sisters and listens and obeys well unlike rich kids his age. I think a kid from a humble family is better than a rich kid in terms of character.

I believe my kids would have a bright future if they could go to school regularly though I cannot afford for them to do so. Think about it. I have to spend 10,000 KHR (10 USD) – and it’s not that small of an amount – everyday for food. So my monthly expenses for food is 300,000 KHR (300 USD). Not to mention, I have to pay for rice, utilities, rent, and so on. If I let my kids go to school regularly, I cannot make it at the end of the month.

My kids want to learn English, but I cannot let them. All I can do is buy a book for them to learn at home. I asked the teacher whether my kids were smart in school and they said my kids were the best. Both of my sons are the best. It’s my sin from my past life that I cannot afford for my kids to go to school. But unlike other mothers who do not care about their kids’ progress in school, when I get home from work, I always ask my kids what they learned that day. Since I have no inheritance for them, as a mother, that’s all I can do for them.

I think about my life all the time. My mother passed away when I was young, just six months after giving birth to my younger sister. I thought I would never get married if I couldn’t make enough money. We came to Phnom Penh after I reached puberty and my sister was a bit bigger. Our financial situation was better because my sister was working. But then I got my first abortion and got married. After that, my father died and my older sibling sold our land. That was when I had another abortion, my third child. We’ve been poor since then. I’ve been praying to god asking for help but nothing happens.

Yesterday or the day before yesterday, the school called for a parent-teacher conference. I went and they asked why my kids have stopped coming to school. I told them it was because I was poor. And then they asked why I became a parent if I had no ability to raise a child. I replied, “What was I supposed to do? I tried my best but it didn’t work out. Should I just rob or steal to make it happen?”

For example, when he gets his paycheck, he knows I need the money, but he only gives me some. You know men nowadays; needless to say, they are…tears come to my eye when I try to talk about this. My sister lives with us and he’s not happy about it. That is why he always picks fights with me. He is also younger than me. He’s still young and beautiful. That’s why. He loves his kids though. He hangs out a lot outside with his friends and stuff, so he always finds faults in me, but he never beats me.

I had a fiancé who was a widower before I met my husband. My husband worked on the construction near my factory. One day he asked me for some water. Then he touched my hand and I was like, “Why are you so rude? You don’t even know me.” After that, he followed me around and came to my house to ask for my hand in marriage. At that time, my late father was still alive so he advised me to think it over between a bachelor and a widower. He said it was better to live with a bachelor. Since I didn’t love either of them, I just followed my father’s advice and got married to my current husband. But it was only ten short years of happiness. After my first abortion, ten years later, things got rough.

The way I see it, if your parents are alive you dare not refuse their advice or complain. If you follow your parent’s advice you will blame them for your unhappiness. However, that is not the case for me. All I can do is be regretful and accept this decision as a sin from a previous life. If my father were alive, I would blame him as well for his misjudgment. I just feel sorry for myself. My life is an endless sad story. I don’t want to talk about it anymore.

This interview has been edited. It was conducted in two parts. The first took place on August 4, 2014. at the shoe factory where Channa was worked. The second time we met was on August 9, 2014, at the apartment complex where she lives on the outskirts of Phnom Penh, Cambodia. She quit her job at the shoe factory. You can read the original interview here

Primary Voice is a collection of primary source interviews dedicated to documenting the living stories of garment factory workers worldwide. It was created by urbanist Mikaela Kvan. To read more interviews and to get in touch visit www.primaryvoice.org.

Matt is a 28-year-old garment worker in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Photo by Sok Chanrado

I’ve been working in garment factories since 2004. It’s been ten years. During those years, a lot in my life has changed. I used to live with my aunt before I started working so I would do all of the chores around her house. Now that I earn my own income I can afford to buy whatever I want and I can help my younger siblings go to school. I have two sisters and one brother. I am 28, my brother is 26, the third is 24, and the last one is 19 years old. My two younger sisters also work in garment factories but our brother goes to university.

I had a rough childhood so I want to forget about it. When I was young I sold things in the market like fish and meat. I sold anything I could. I would sell things for other people, too, in order to save for my siblings and me to go to school. We lived in Sihanoukville then and my family was poor. All of my siblings had to work to earn money for school at the age of seven or eight. In 2004, my mom passed away. That’s when I quit school.

My father was a drunk. He always caused problems – swore at us or threw things around the house or kicked us out. Because of his abuse I decided to bring my siblings to Phnom Penh to live with our aunt. After living with her for about 4 months we had to rent our own house. The financial burden was too much for her.

When I was a child I dreamt that I would finish school and get a good job that could support my family and me. When my mother died I had to quit school to work because I am the oldest sibling. I was only in fifth grade. I felt such pity for myself after quitting school. Ultimately, I had no choice. Time wouldn’t stop. I had to look forward and take care of my siblings.

I must sacrifice myself for their sake. It hasn’t been easy. At times I feel really irritated and stressed but when my siblings behave themselves, and don’t give me a hard time, I feel my capabilities are limitless. Even if we don’t have parents, we still have each other. As the eldest sibling I feel a great responsibility to be a good role model for my brother and sisters.

Financially, we can only depend on ourselves. Unlike others whose parents are still alive, we can’t survive without working. I don’t have the luxury of living that way. If it were up to me I would not work in a garment factory. I want to open a small shop where I have the potential to earn income daily. With my current job, I have to wait until the end of the month to get a paycheck from the factory. By that time, I need to pay rent and it seems I have nothing left. Unfortunately, I don’t have the ability to realize this dream for myself right now because I need to support my brother who is in university. Once he graduates I could probably quit my job at the garment factory and open my own shop. I’m optimistic about my future. When my siblings were young, I worried they wouldn’t listen to me. But it turns out my siblings are good kids. I hope the future will be easier. Since I am having a hard time for their sake now, I believe they will think about me when they have jobs.

This interview has been edited. It was conducted on August 10, 2014, outside Matt’s room in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. You can read the original interview here

Primary Voice is a collection of primary source interviews dedicated to documenting the living stories of garment factory workers worldwide. It was created by urbanist Mikaela Kvan. To read more interviews and to get in touch visit www.primaryvoice.org