“You have forgotten the Tazreen fire incident but our actual suffering has just started,”

says Anju, who experienced severe head, eye and other bodily injuries during the fatal Tazreen Fashions Ltd. fire in Bangladesh in November 2012 that killed 112 garment workers.

Survivors of the Tazreen fire who recently talked with Solidarity Center staff in Bangladesh say they endure daily physical and emotional pain and in many cases, have little or no means of financial support because they cannot work. Some, like Anju, who is unable to work, have never received compensation for their injuries.

Bangladesh’s $25 billion garment industry fuels the country’s economy, with ready-made garments accounting for nearly four-fifths of exports. Yet many of the country’s 4 million garment workers, most of whom are women, still work in dangerous, often deadly conditions. Since the Tazreen fire, some 34 garment workers have died and 985 have been injured in 91 fire incidents, according to data collected by Solidarity Center staff in Dhaka, the capital.

Some 80 percent of export-oriented ready made garment (RMG) factories in Bangladesh need improvement in fire and electrical safety standards, despite a government finding most were safe, according to a recent International Labor Organization (ILO) report.

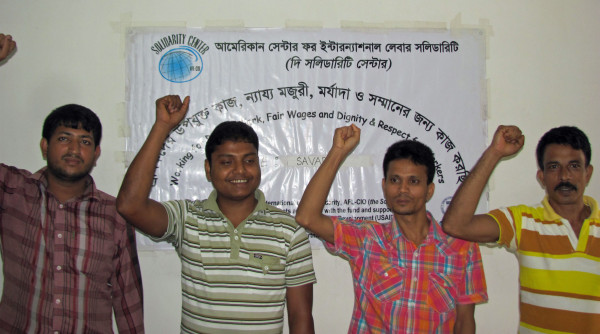

The Solidarity Center has had an on-the-ground presence in Bangladesh for more than a decade. Through Solidarity Center fire safety trainings for union leaders and workers, garment workers learn to identify and correct problems at their worksites. But fewer than 3 percent of the 5,000 garment factories in Bangladesh have a union. ” Despite workers’ efforts to form unions, in 2015 alone the Bangladeshi government has rejected more than 50 registration applications—many for unfair or arbitrary reasons—while only 61 have been successful. The rejections have jumped significantly from 2014, when 273 unions applied and 66 were rejected.

So that the world does not forget, here is the story of Anju and others who survived the Tazreen fire.

Anju, 45, suffers from neurological and other complications resulting from the injuries suffered during her escape from the Tazreen fire. She says the income her husband earns pulling a rickshaw cannot support their four children and pay for her medicine.

“The treatment cost is high and we cannot bear it,” she says. “Everyday life is difficult.”

Shahnaj Begum, 48, and her daughter Tahera Begum, 30, both survived the Tazreen factory fire. Shahnaj was severely injured, including the loss of her right eye. Shahnaj received some compensation, but it was not enough to pay medical bills and ongoing support.

“Many lives could have been saved if the factory was not locked. The biggest tragedy for us is the culprits have not been punished.”

Jorina Begum, 25, cannot afford medical treatment for the injuries to her spine and body she sustained at Tazreen, and her physical condition is worsening. Jorina’s sister, also injured when the factory burned, died recently. Now there is no one left to support the family. She says two things will give her peace of mind:

“I want compensation so that I can manage the support of my family members and I want to see that the person who is responsible for it is punished.”

Bilkish Begum says she and other workers at a garment factory in Bangladesh could not discuss implementing fire safety measures with their employer – even after the deadly blaze at Tazreen Fashions factory killed 112 workers three years ago. Only when they formed a union, which provides workers with protection against retaliation for seeking to improve their workplace conditions, could they take steps to help ensure their safety.

“Things have improved a lot regarding fire safety once we formed union as now we have the power to raise our voice,” she says.

Bilkish, 30, now a leader of a factory union affiliated with the Sommilito Garments Sramik Federation (SGSF), is among hundreds of garment workers who have taken part in Solidarity Center fire safety trainings this year. The Solidarity Center works with garment workers, union leaders and factory management to improve fire safety conditions in Bangladesh’s ready-made garment industry through such hands-on courses as the 10-week Fire and Building Safety Resource Person Certification Training.

“I used to be afraid about fire eruption in my factory,” Bilkish says. “But after attending trainings, I feel that if we work together, we can reduce risk of fire in our factory.”

Fire remains a significant hazard in Bangladesh factories. Since the Tazreen fire, some 34 workers have died and at least 985 workers have been injured in 91 fire incidents, according to data collected by Solidarity Center staff in Dhaka, the capital. Incidents resulting in injuries include at least eight false alarms.

In January, after a short-circuit caused a generator to explode at one garment factory, Osman, president of the factory union and Popi Akter, another union leader, quickly addressed the fire and calmed panicked workers using the skills they learned through the Solidarity Center fire training. They also worked with factory management to correct other safety issues, like blocked aisles and stairwells cramped with flammable material.

Many workers who have taken part in the trainings say they are equipped to handle fire accidents.

“We are now confident after the training that we can help factory management and other workers if there is any incident of fire in our factory,” says Mosammat Doli, 35, a leader of a union affiliated with the Bangladesh Garment and Industrial Workers’ Federation (BGIWF). “From my experience at my factory, I have seen that an effective trade union can ensure fire safety in the factory as it can raise safety concerns,” he said.

Fewer than 3 percent of the 5,000 garment factories in Bangladesh have a union. And according to the International Labor Organization, 80 percent of Bangladeshi garment factories need to address fire and electrical safety standards. Yet, despite workers’ efforts to form organizations to represent them this year, the Bangladeshi government rejected more than 50 registration applications—many for unfair or arbitrary reasons—while only 61 were successful. This is in stark contrast to only two years ago, when 135 unions applied for registration and the government rejected 25 applications, and to 2014, when 273 unions applied and 66 were rejected.

Without a union, workers often are harassed or fired when they ask their employer to fix workplace safety and health conditions.

Because his workplace has a union, which enabled Doli to participate in fire safety training, he—like Osman and Popi Aktee—already has potentially saved lives. Together with other union leaders, he helped evacuate workers and extinguish a fire in their garment factory.

Shahabuddin, 25, an executive member of his factory union, which is affiliated with SGSF, is among Bangladesh garment workers who see firsthand how unions help ensure safe and healthy working conditions. He says his workplace had no fire safety equipment—until workers formed a union and collectively raised the issue of job safety.

“Now management conducts fire evacuation drills almost regularly. We did not imagine it just a few years back. As we formed union, many things started changing,” he says.

Mushfique Wadud is Solidarity Center communications officer in Bangladesh.

The three-year anniversary of the November 24, 2012, fire that killed 112 Bangladesh garment workers at the Tazreen Fashions Ltd., factory offers a time to reflect on garment workers’ ongoing struggle for workplaces where they will not be killed or injured and for jobs that will support their families.

The Tazreen fire was preventable, as was the collapse of the multistory Rana Plaza factory five months later in which more than 1,130 garments workers died and thousands more were severely injured.

Workers at Tazreen and Rana Plaza did not have a union or other organization to represent them and help them fight for a safe workplace. Without a union, garment workers say they are harassed and even fired when they raise safety issues with their employer. They are not trained in basic fire safety measures and often their factories, like Tazreen, have locked emergency doors and stairwells packed with flammable material.

Despite the many obstacles to forming organizations and achieving a voice at work, garment workers are at the forefront of pushing for change at their factories. With our strong and long-term grassroots connections in Bangladesh, the Solidarity Center allies with garment workers to provide ongoing training for factory-level union leaders on topics such as gender equality, workers’ legal rights and fire safety.

This photo essay gives voice to the sorrow, but also the hope, of the 4 million workers who toil in Bangladesh garment factories.

1. Bangladesh’s 4 million garment workers, mostly women, toil in 5,000 factories across the country, making the $25 billion garment industry the world’s second largest, after China. Yet many risk their lives to make a living. In the three years since the fatal Tazreen Fashions Ltd. factory fire, some 31 workers have died and at least 935 people have been injured in garment factory fire incidents in Bangladesh. Credit: Law at the Margins

2. Some 112 garment workers were killed in a blaze that swept through the Tazreen factory on November 24, 2012. Hundreds more were injured and like Tahera (above), will never be able to work again. Survivors say they endure daily physical and emotional pain, and often cannot support their families because they cannot work and have received little or no compensation. Solidarity Center/Mushfique Wadud

3. Tens of thousands of Bangladesh garment workers held rallies on May Day this year to highlight the need for the freedom to form worker organizations to ensure safe and healthy workplaces. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

4. With few jobs available that pay a living wage, more than 600,000 Bangladeshi workers migrate each year. Yet, “after two years, after three years, they are not getting their salary,” says Sumaiya Islam, director of the Bangladesh Migrant Women’s Organization (BOMSA). “After spending $1,000 (to labor recruiters), they are not getting paid.” Credit: Shahjadi Zaman

5. Migrants from Bangladesh also risk their lives when going overseas for jobs. In June, Bangladesh families rallied to demand the government punish traffickers after many Bangladesh workers were among migrants stranded on abandoned boats by unscrupulous labor traffickers. “I did not get anything to eat for 22 days and just survived by eating tree leaves,” Abdur said, describing his journey to Malaysia. Credit: Solidarity Center/Mushfique Wadud

6. On April 24, 2013, the multistory Rana Plaza factory collapsed, a preventable tragedy that killed more than 1,100 garment workers and injured thousands more. On the two year anniversary in April, family members and friends gathered at the site of the building to commemorate their loss. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

7. Thousands of garment workers, like Mosammat Mukti Khatun (above, looking at the Rana Plaza rubble) who survived the Rana Plaza disaster, remain too injured or ill to work and support their families. Survivors and the families of those who lost loved ones in the collapse say they are struggling to make ends meet, unable to pay rent, send their children to school or provide for other basic needs. Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

8. Days before tens of thousands of Bangladesh garment workers rallied on the two-year anniversary of the Rana Plaza collapse, the ITUC released a report that found “a severe climate of anti-union violence and impunity prevails in Bangladesh’s garment industry. The violence is frequently directed by factory management. The government of Bangladesh has made no serious effort to bring anyone involved to account for these crimes.” Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

9. The Solidarity Center launched the Bangladesh Worker Rights Defense Fund in April 2014, following an increase in violence and harassment against workers who were seeking to form unions to protect their health and rights on the job. Donations of more than $15,500 helped to provide costly medical treatment for organizers beaten or attacked while speaking to workers about their rights, and temporary food and shelter for workers fired for trying to improve their workplace. Credit: Solidarity Center/Shawna Bader-Blau

10. Despite employer and government resistance to workers’ efforts to form organizations to improve job safety, in the Dhaka export processing zone alone, 40 of the 103 factories include workers’ welfare associations, which are similar to unions. Credit: Solidarity Center/Mushfique Wadud

11. Women garment workers primarily fuel Bangladesh’s $25 billion a year garment industry, yet women are “still viewed as basically cheap labor,” says Lily Gomes, Solidarity Center senior program officer for Bangladesh. “There is a strong need for functioning factory-level unions led by women,” says Gomes, who is leading efforts to help empower women workers to take on leadership roles at factories and in unions throughout Bangladesh. Credit: Solidarity Center/Kate Conradt

12. With strong and long-term grassroots connections in Bangladesh, the Solidarity Center provides ongoing training for garment worker union leaders on topics such as gender equality, workers’ legal rights and job safety. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

13. Garment worker union leaders sharpen their skills through regular Solidarity Center workshops, such as this one on financial management. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

14. Hundreds of garment worker union leaders have participated in this year in the Solidarity Center’s 10-week fire safety certification course. “People who worked at Tazreen and Rana Plaza had no training and had no union,” says Saiful, who took part in a recent fire training. “This training is about making sure those things never happen again.” Credit: Solidarity Center/Rakibul Hasan

For three years the victims of the worst factory fire to hit the fashion industry in recent times have been waiting for compensation. Now, finally, hope is on the horizon.

Around 120 garment workers burnt to death and hundreds more were injured when flames engulfed the multi-floor Tazreen garment factory in Bangladesh on 24 November 2012.

Trapped behind locked exists, workers jumped for their lives from the upper floors of the building, with more than a hundred sustaining permanent, life-changing injuries.

Like thousands of garment factories in Bangladesh, the workers at Tazreen fashions were making clothes for global retailers destined for Western wardrobes.

IndustriALL Global Union, together with the Clean Clothes Campaign, C&A and the C&A Foundation have set up the Tazreen Claims Administration Trust to compensate victims for losing loved ones, loss of income and to pay for much-needed medical treatment. Claims are already being processed and victims can expect to receive payments in the coming months.

Brands and retailers with revenue over US$1 billion are being asked to pay a minimum of US$100,000 into the fund for victims.

Certain brands that sourced from Tazreen, including C&A, Li & Fung (which sourced for Sean John’s Enyce brand) and German discount retailer KiK have now paid into the fund.

But more brands must face up to their responsibilities and pay.

That includes Walmart, Tazreen’s biggest customer. The anniversary falls just as the retail powerhouse stands to profit from US$50 billion of consumer spending on Black Friday this week.

Other brands that sourced from Tazreen and have not paid are U.S. brands Disney, Sears, Dickies and Delta Apparel; Edinburgh Woolen Mill (UK); Karl Rieker (Germany); Piazza Italia (Italy); and Teddy Smith (France).

Three years have passed but we cannot let brands forget the victims of Tazreen. Now it is time for a measure of justice.

by Christina Hajagos-Clausen, Textile and Garment Industry Director at IndustriALL Global Union. IndustriALL Global Union represents garment workers around the world. It is one of the key drivers of the Bangladesh Accord on Fire and Building Safety signed by more than 200 global fashion retailers and covering more than two million garment workers in 1,500 factories.

Photo credit: IndustriALL Global Union

‘Black Friday’ 2015 is just around the corner. Traditionally it is the day after Thanksgiving in the US when shops do an all-out sale giving the customers a chance to stock up for Christmas. Well that’s what it used to be about. Be it the US or UK, in recent years, ‘Black Friday’ has come to symbolise something more interesting, our insatiable appetite to consume. We all remember seeing the images on TV, hearing the news update on radio and saw the news headlines of the incidences which marred this day. So much so that this year leading UK superstore have announced that they will not be participating in this year’s event even though all other major super stores are[i].

One may well ask, what Black Friday has to do with ‘sustainable development’? One word………..everything! Research after research has found that our demand for goods will soon out strips the natural resources available to make them. We know that in the UK garment workers are earning as little as £3 per hour for their work (University of Leicester Feb 2015[ii]). And those in faraway lands like Bangladesh, Vietnam, Myanmar and even Ethiopia are getting paid approximately £25-30 per month[iii]. But as consumers, we close off part of our thinking mind and all queue up, physically and on-line, waiting for that deal on Black Friday.

Sustainability in the fashion industry has been addressed right through its value and supply chain. In the manufacturing sector of garments, there are all kinds of machinery that optimises water usage for washing and drying of textile and therefore has a knock on effect on the level and amount of electricity and gas used. Buildings are more ‘green’ by using solar power or alternative sources of energy and reuse and recycle rain water amongst other things. More and more manufacturers are also looking more intently on how they engage with their labour force and the provisions that are available for them. Manufacturing factories in Bangladesh are actively pursuing ‘green manufacturing’ starting with the factory space and also the environment and support for their workers[iv].

Worn Again is working with H&M and Kerring[v] to not just recycle or upcycle but create new textile based on a ‘circular resource model’ from old or ‘end of use’ clothes. New materials are also being produced from natural fibers like pineapples or banana and from seed to harvesting all aspects of the plant/ fruit is reused. M&S’s ‘SHWOP’[vi] or Patagonia’s ‘Worn Wear’[vii] are two high profile schemes which promotes and advocates ‘longer-life’ for our clothes. There are workshops on knitting in groups bit like ‘Book Clubs’. Critiques of the schemes say that these schemes are destined for the wardrobes of the rich and middle-classes. Not for the mass public. Also that dropping of our ‘worn’ clothes to the ‘poor’ of the developing nations can actually cause problems for local brands, retailers and manufacturers[viii].

In a recent BBC documentary programme, ‘Hugh’s War on Waste’, the host looks to engage with individuals who do not believe that waste is truly recycled. They are taken to a local recycling processing plant and the sceptic recyclers are still not convinced by the argument for recycling waste. It is only when they are shown actual everyday products made from recycled material that we see the recycling sceptics change their outlook.

But if it is facts we are looking for there is plenty out there in the form of research, films, images, case studies and much more. For instance the recent film ‘The True Cost’[ix] has given a very detailed breakdown of how the fashion supply chain is set up and is costing. It has been distributed in cinemas, is available online and through social media platforms. So very easily available and accessible and we still have the situation of people not following through and buying less or not queuing for ‘Black Friday’.

So far I have concentrated only on the consumption habits of developed countries. However it is the with consumers of China, India and elsewhere that brands and retailers are trying to establish a relationship with. And that is because in emerging countries material consumption lead the way as more people have disposable income and also want to have the opportunity consume or at least aspire to consume as their counter parts in developed countries[x].

So what we see now is brands, luxury brands and every day retailers positioning themselves in these new markets. It is quite normal to see nappies for babies being sold in main cities and towns of these new territories. Long gone are the days when people would use ‘terry cloth’ nappies for their babies not only because they are time consuming to maintain but also they are seen as being ‘traditional’ and not representative of the ‘modern life’ that they now live.

So attitudes are changing everywhere. It’s cyclic. In that the developed world have started thinking about ‘sustainable development’ in all walks of life. They are exploring how corporations, supply chains and individuals can make a difference. The emerging and developing countries with a growing number of people with spending power and disposable income now aspire to consume and become active participants in this global consumer market. Internet has increasingly made everything accessible within a click of a button. Social media shows you trends on a daily, hourly, minute by minute basis to satisfy ones desire.

So the notion of ‘sustainable development’ is admirable but seemingly unachievable. Unless of course as in the case of fashion you have groups like Fashion Revolution Day and their mission to connect consumer to their clothes through the ‘#who made my clothes?’ FRD asks the consumer to do the following:

- Be curious – Look at your clothes with different eyes. Ask more than “does this look great on me?”. Ask “#who made my clothes?”.

- Find out – Get to know your clothes even better.

- Do something – tweaking the way your shop, use and dispose of your clothing

Be curious is the start point of looking at our personal shopping habits. Before we go get the latest design at a cut price from the shop, the question we must ask is ‘do I really need to buy this?’, ‘Will I wear it more than once?’, ‘do I know how to take care of it?’ and what will I do when I have had enough of it?’. These questions are alongside asking the brand ‘#who made my clothes?’ Fashion Revolution has run a very successful global campaign in 2014 and 2015 with consumers, celebrities turning their clothes ‘insideout’ taking a selfie of it and asking the brand ‘#who made my clothes?’

This new curiosity will lead us to the next step ‘Find Out’. If we do not know exactly what is happening then it is difficult to change our behaviours and attitudes. There are various organisations who work on specific issues like living wage, organic cotton or on themes ‘Fair Trade’. They are a good start point for any search[xi]. There are also apps available which will assist you whilst you are shopping to find out more about the social and environmental impact of the item[xii]. New apps are coming are being developed and trialled and aims to provide more detailed information on the item of clothing origin.

‘Do something’ is personally my favourite. It can be you ask the brand, #who made my clothes? Or look at projects like http://loveyourclothes.org.uk/ set up by WRAP which gives you tips on how to manage your clothes, revamp it and much more. As mentioned earlier, high street stores like M&S or brands like Kerring have also tried to inspire their customers with alternatives to just throwing our clothes away. What is possible is sometimes difficult to choose, so a helpful list is available from Fashion Revolution’s booklet, ‘How to be a Fashion Revolutionary’[xiii]

As discussed earlier, the consumer at present is detached from what they consume be it the clothes we wear or other products. We have seen that it is only when they come face to face with evidence, is it that they start to explore further the issues on hand. So that we can move away from the future of diminishing natural resources and an un-sustainable environment we need to change attitudes through curiosity, finding out and doing something.

Author – Maher Anjum – Sustainable Sourcing and Supply Chain (Garments, Textiles and Fashion) Consultant, Operational Director Oitji-jo Collective (Part-Time), Associate Lecturer, London College of Fashion and Member, Global Advisory Committee, Fashion Revolution.

References

[i] http://www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk/news/northern-ireland/asda-axes-black-friday-but-rivals-tesco-sainsburys-amazon-argos-currys-pc-world-halfords-and-john-lewis-banking-on-bonanza-34188894.html

[ii] http://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/sustainable-fashion-blog/2015/feb/27/made-in-britain-uk-textile-workers-earning-3-per-hour

[iii] http://www.waronwant.org/sweatshops-bangladesh

[iv] http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/22/business/energy-environment/conservation-pays-off-for-bangladeshi-factories.html

[v] http://www.kering.com/en/press-releases/hm_kering_and_innovation_company_worn_again_join_forces_to_make_the_continual

[vi] http://www.marksandspencer.com/s/plan-a-shwopping

[vii] http://www.kering.com/en/press-releases/hm_kering_and_innovation_company_worn_again_join_forces_to_make_the_continual

[viii] http://edition.cnn.com/2013/04/12/business/second-hand-clothes-africa/

[ix] http://truecostmovie.com/about/

[x] http://www.worldwatch.org/node/810

[xi] https://www.fashionrevolution.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Website_HTBAFR_Booklet_BCxFR_Print.pdf

[xii] https://www.fashionrevolution.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Website_HTBAFR_Booklet_BCxFR_Print.pdf

[xiii] https://www.fashionrevolution.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Website_HTBAFR_Booklet_BCxFR_Print.pdf

I am sure that you have a closet overflowing with clothing. Chances are you might even have items that still have the swing tickets attached. Have you ever looked at the care label to see where your clothing was manufactured? Fast fashion isn’t going anywhere anytime soon. In fact fast fashion was created for this simple reason: to get us buying more and more and without much thought into where these garments are made.

I am hoping that by the time you finish reading this piece, something would have shifted. For one you will take a look at the care labels of your clothing and find out who is responsible for it and that you will hopefully reevaluate your shopping habits. Fast fashion companies cut corners, they use cheaper fabrics and cheap labor. It is simply exploitation. There is the argument that fast fashion creates jobs but when people are exploited it simply isn’t right.

Cape Town was aflutter recently when H&M (Hennes & Mauritz) opened its first store in South Africa. More stores are planned including Johannesburg’s Sandton City as well as others in Southern, East and West Africa.

It is always great to have brands open stores in our country, least of all when you know that jobs will be created. It is reported that about 600 jobs were created leading up to the opening of the V&A Waterfront and Sandton City stores. Staffers, around 60, were sent to Sweden for training. H&M plans to have as many as 1 500 people employed within the next 12 months.

The buzz continues but there is one fundamental problem with brands like these and it seems very few people know what really happens behind closed doors. In this case, behind the doors of the factories that produce these garments. This lack of knowledge was evident from the social media images from fashion bloggers to local personalities applauding H&M on their opening.

It was not long ago, in fact only two years prior, in April 2013 when the deadliest industrial disaster in the history of clothing manufacturing took place. The collapse of the Rana Plaza building in Bangladesh, claiming the lives of 1 138 of its workers.

Two years after this tragedy, H&M is still behind on correcting the fire and safety hazards in its factories in Bangladesh according to the joint report released by the International Labor Rights Forum, Clean Clothes Campaign, Maquila Solidarity Network, and Workers Rights Consortium. These fire and safety hazards are the working conditions their workers are forced to work under making sure that fast fashion reaches our stores timeously. Repairs, which include installation of fireproof doors and the removal of locking or sliding doors from fire exits are some of the issues that have not been addressed.

These are repairs that affect the staff working in these factories. If not dealt with, it could have disastrous outcomes, like that of April 2013. It appears that more attention is placed on pushing out the orders as opposed to the people who make these garments. Will these factories get away with these hazardous conditions if they were in developed countries? No! Cheap labor is simply that; cheap. Bangladeshi workers who sew for H&M toil in extremely dangerous conditions. So can you really say that their fashion is cheap? Cheap in price definitely but costly on the scale of human lives. Par Darj, the country manager for H&M South Africa described H&M’s merchandise as “democratic fashion” high quality, easy and affordable for people who ordinarily might not be able to buy fashion. How democratic is this model if H&M chose to open their first store at the V&A Waterfront? The only people who benefit from the fast fashion system are the executives who are some of the richest people in the world.

The H&M store in Cape Town is 4700 square meters and is said to be one of their biggest stores in the world. Rumor has it that there might be a section carrying local designers in the near future. Could this be why they are exploring the feasibility of opening a local manufacturing facility? Par Darj said H&M already has a production factory in Ethiopia, opened in 2014. “We will see what is possible in South Africa”. One would hope that the working conditions in this factory are safer than the one in Bangladesh or the potential of a factory opening in South Africa will not cost anyone their life.

Are South African malls in the future only going to comprise of top international brands? The likes of Burberry, Forever 21, Top Shop, Zara etc. It could be, unless you reevaluate your shopping habits.

The True Cost film will make you rethink your fast fashion addiction. I can’t help but think of the interview with Shima Akter, a 23-year-old Bangladeshi garment worker who was beaten by her factory supervisors for organizing and leading a workers’ union in the hopes to get better working conditions ‘I don’t want anyone wearing anything which is produced by our blood.’

I encourage you to watch The True Cost to understand just where your clothing comes from and the price others are paying for it.

Who Makes Our Clothing? | Livia Firth | The True Cost

Thanapara, a small village on the borders of Bangladesh surrounded by mango tress and the Ganga river, is a place at the very end of the world. Probably no one would expect that a well-known organization, Thanapara Swallows, which cooperates with many foreign partners has a base here and employs dozens of local women in its garment workshop.

The organization Thanapara Swallows produces cotton clothes for prestigious brands such as People Tree from UK and the Fair Trade Company from Japan, as well as for my small e-shop TukTuki. All the products are made according to the rules of fair trade – with respect for the producers and the environment. When I visited Thanapara, the organization was just in the middle of the accreditation process. The workers were marking emergency exits, concreting the floor and improving other details required by the accreditors. In November 2013 Thanapara Swallows got the official World Fair Trade Organization mark, which declares that the production process is running in accordance to the ten fair trade principles.

When I saw what is happening behind a high wall at the end of the village for the first time, I thought it must be a miracle. The whole production process is completely by hand and the technologies reminded me museum exhibits. Wooden looms, smouldering fires under the pots with dyes, pedal sewing machines – the women from Thanapara Swallows are able to make the highest-quality products using these tools.

The crazy manufacturing process reminds me very much of the market in the nearest city, Sardah. Dozens of workers in colourful saris carry thread, cloth and products from one place to the other, spreading the fabrics on the roof to dry them and carrying the wood while their colleagues are just sleeping after lunch or breastfeeding children. The women from the Thanapara village comprise the vast majority of the workers.

The organization Thanapara Swallows is the biggest employer in the area and the only opportunity for the women from surrounding district to get a paid job. About two hundreds of them are employed in the workshop and about one hundred work at home. Dozens of experts are also employed in the development project which is run from the profits of production. The nursery and elementary school are just two of the projects contributing to local community development. Thanks to these projects, the women working in the workshop can be close to their children, come to breastfeed them during the lunch break and take them home from school.

There is a coil of thread at the beginning of the whole process. It is because cotton threads are the only product which is bought. The rest of the production is entirely carried out by hand in the Thanapara workshop. First of all the threads are dyed. The dyes are made in two big pots by a trial and error method. I had to laugh when I first saw the manager standing in front of the computer with a piece of cloth comparing its colour with the colour on the monitor. It was less humorous for me to look at the workers dying the threads in boiling water using two huge bamboo sticks, hanging them on every single free space to dry them and making bobbins. You need only a gorgeous wheel and two skilful workers to prepare the warp for a loom.

Weaving is said to be the most difficult and most glamorous work here. Pushing the treadle, binding the threads, counting the sequences is done enormously quickly and can be managed only by the most experienced workers.

The biggest room is used for sewing and embroidering. The women use mechanical pedal sewing machines, only three of them are electrical. On one hand the pedal machines are slower and get stuck from time to time. On the other hand you can keep sewing even if the electricity doesn’t work, which happens quite often here. The “Iron Man” is a penultimate link in the production chain. The worker of this poetical position does simply…ironing. At the very end of the production there is the oldest employee of Thanapara Swallows. The respected old woman is responsible for the quality control and no piece of cloth can be packed without her agreement.

Each product of Thanapara Swallows passed through the hands of dozens of men and women. It is unbelievable how cheaply the goods can be produced and sold. The reason is the very low level of salaries – the minimum wage in the garment industry is 5300 Bangladeshi Taka, about 50 Euros. The workers in Thanapara Swallows workshop are paid according to their productivity. The most skilful can earn more than two minimum wages a month. The money is enough to live on, buy school supplies for children and maybe even to save something. The organization also administers a fund helping the employees in case of illness or inability to work. It is the community way of management which transfers a garment factory into the fair trade workshop. All workers can decide about important aspects of the organization and everybody can also benefit from the organization’s earnings and services. Even if the working conditions and standards are incomparable to our perception of “decent labour” the situation is getting better and better. This is thanks to the dialogue of the management and employees, as well as thanks to the independent controls of World Fair Trade Organization and other partners.

My name is Jessmin Begum, I am 31 years old and I have been working in the garment industry for 15 years.

I have worked in six different factories in total. In those 15 years, I have seen many different labels. I have manufactured clothes for brands such as H&M, Gap, Walmart, S.Oliver, C&A, Zara. I first started working in the garment sector after completing my Higher Standard Certificate of education. A neighbour told me about a job in a garment factory; so I joined. In my first job I was a ‘helper’. That means I was cutting the threads from the seams of the clothing. I did that job for a month and then I was promoted to a seamstress. I worked in that factory for one year. Then I got a job at another factory where the salary was higher. I worked in that factory for the next nine years and earned 7700 Taka (85€/£62/$96) including overtime.

That factory was in an Export Processing Zone (EPZ). In the EPZ, a different labour law applies. The Government regulates it through an authority called BEBZA (Bangladesh Export Processing Zones Authority). My first job had been outside EPZ. You can tell the difference. They pay wages in a timely manner on the seventh day of the following month, they give regular weekend breaks and holiday pay.

The government ruled that each factory in the EPZ should have a Workers’ Welfare Committee. When it came to the election for that committee, my friends encouraged me to run. They made posters and banners. The committee is comprised of 12 members. When it came to the election of the chair, the other eleven didn’t want to take on that role, so I did it. The committee is elected every two years and I was re-elected twice.

My duty as chair was to meet with BEBZA. Sometimes they came to the factory, which meant I had to leave my work and go to meet them at the General Manager’s office.

The factory owner put me under pressure.

In order to make a good impression, the factory owners told the Authority that they could speak to me at any time. However, I was pressurised not to go by the factory owner, the middle management, my line manager and supervisors. So I asked the people at the BEBZA why they called on me during working hours as my manager did not want me to leave my work.

Before I explain what happened, I would like to tell you a bit more about the factory

The factory had five floors and on each floor there were 400-500 people, around 2500 workers in the building, out of which there were just 12 committee members appointed. We were all working on different floors and in different jobs. During lunch break, we would sit together and discuss peoples’ complaints. We gathered information. When BEBZA came, sometimes we all went to see them, but often I went alone to pass on the complaints.

I was the one who was speaking out.

The others didn’t do that as much. BEBZA used to listen to me. They usually came two to three times a year as a routine check up, and when the workers were protesting.

So, as I said, the factory owner pressured me not to leave work in order to go to these meetings. When the time came for the meeting, they would give me more work. If I normally had to complete 10 garments, they now gave me 15, which would be impossible to finish. So sometimes I couldn’t attend the meetings. If there were no committee representatives who could attend the meetings with BEBZA, they asked the factory owner to send other employees, so he would send a supervisor or one of his relatives.

Whenever I had the opportunity to pass on the workers’ complaints, BEBZA said they would look into the problem. But there was no action. No solution. The law in Bangladesh stipulates working hours from 8am to 5pm, with two hours of overtime from 5pm to 7pm. But the owner pressurised us to work four or five hours of overtime. But you know, we can’t go home every day at 10pm. First of all, there is a security issue for women. Then, when we go home, we still have to cook. At that time I was living with my mother. I was single and my mother cooked for me. But other workers needed to do all that alone, they had to take care of their children and they also had to sleep.

The Authority did not respond to our complaints. There was no action.

So the workers gathered together and wrote the following demands: higher wages, no more than two hours of overtime per day, no insults while working, no beatings and, most importantly, no termination of our employment because of the strike. The last point was particularly important to us, because otherwise they could just fire us.

As the chair, I had a certain amount of power. There were 2500 workers supporting me. The first strike was on 9 February 2003. We told the management and the police that we would continue our strike and our attacks if they did not meet our demands. So they signed.

During my time as chair, we held four protests in total. After the first protest they couldn’t fire me anymore, so they looked for other ways to get rid of me. I was bribed with 200,000 Taka (2200€/£1650/$2570) by the factory owner. He teased me, gave me a bundle of money and said sarcastically:

“Girl, you don’t know how much money is in here. Just take it and go.”

They wanted me to leave the factory because I talked too much. They knew that I had influence. They knew the risk. They knew that if I went to the Authority, they would listen to me. I did not accept the money.

During the last strike, I was four months pregnant. One day I was injured by brick which I blocked from hitting my body with my hand. Workers were throwing bricks inside the factory and the police were throwing them threw back. I finally stopped working at the factory when I gave birth to my baby because I had to breastfeed. I couldn’t be fired when I was pregnant of course, but I resigned because of the baby.

Afterwards I worked in another factory outside of the EPZ for one and a half years where I wasn’t paid on time. I joined the National Garment Workers Federation in 2008 where I work part-time as the Secretary for Women’s Affairs. Now I am in the NGWF I am letting people know about the law and their rights.

I go out on the road a lot and visit workers in their homes. I also work in a factory as a production reporter where I earn 15.000 Taka. At least if I lose my job at the factory, I will still have the job at NGWF .

Unions are important because they encourage the factory owners to listen to us.

If the owner has a tight shipping deadline, he will talk to the union members and say “can you help me out, can you work two more hours” and they will accept. So the conversation begins.

Translated from the original interview in German by Anna Holl which appeared in N21

Translated from the original interview in German by Anna Holl which appeared in N21

Mein Name ist Arifa Sultana Anny. Ich bin 19 Jahre alt. 2 Jahre und sechs Monate lang habe ich in der Textilindustrie gearbeitet. Vor einem Monat verlor ich meinen Job, weil ich den Mund zu weit aufmachte.

Ich arbeitete sechs Tage die Woche in der Fabrik. Jeden Tag von acht in der Früh bis um fünf am Abend. An den meisten Tagen machte ich dazu noch Überstunden von fünf bis zehn am Abend. Dann war ich 14 Stunden in der Fabrik. Manchmal musste ich auch am Freitag arbeiten, also hatte ich keinen freien Tag in der Woche.

Ich stand jeden Tag um sechs Uhr morgens auf, bereitete mich vor und machte die täglichen Erledigungen. Ich musste kochen und das Haus in Stand halten. Um zwanzig vor acht ging ich zur Fabrik.

In der Fabrik war es eine Tortur. Es gab fünf Stockwerke und pro Stockwerk nur zwei Toiletten und die waren nicht einmal sauber. 400-500 Leute arbeiteten in der Fabrik. Es gab keinen Doktor, keine Kantine und keinen Gebetsraum. Wir stellten Kleidung für ZeroXposur (eine amerikanische Outdoormarke), Li and Fung (Supply Chain Manager aus Hong Kong, mit Kunden in Europa: Recherche folgt) und Dungafree her. Ich war in der Jacken-Produktion und mein Job war „Checker“. Nachdem die Jacken fertig genäht waren, war es meine Aufgabe, sie auf Fehler zu kontrollieren. Wenn ich einen Fehler fand, ging ich zu der Person, die diesen Arbeitsschritt gemacht hatte, damit sie den Fehler korrigierte. Für diesen Job bekam ich weniger Geld als die NäherInnen.

Ich wurde ständig unter Druck gesetzt

Wenn ich einen Fehler übersah und die VorarbeiterInnen fanden es heraus, sagten sie mir, dass ich meinen Job nicht gut mache. Wenn die VorarbeiterInnen einen Fehler fanden, ließen sie mich leiden. Sie strichen mir Stunden von meiner Anwesenheitsliste, für die ich dann nicht bezahlt wurde, obwohl ich gearbeitet hatte.

Eines Tages hörte ich von der National Garment Workers Federation (NGWF). Durch diese Föderation erfuhr ich von den Gewerkschaften. Also wollte ich eine Gewerkschaft in meiner Fabrik gründen. Dafür braucht man die Unterstützung von 30 Prozent der ArbeiterInnen.

Als ich das Thema zum ersten Mal ansprach und den KollegInnen erzählte, dass ich eine Gewerkschaft gründen wolle, hatten sie zuerst Angst vor Drohungen des Managers und Angst ihren Job zu verlieren. Ich arbeitete jeden Tag. Ich sprach die anderen ArbeiterInnen während der Mittagspause, nach der Arbeit und in ihren Häusern an. Und manchmal sagten die ArbeiterInnen: „Nein“. Ich erzählte ihnen wieder und wieder von der Gewerkschaft und ein „Nein“ wurde oft zu einem „Ja“.

Als die Fabrikbesitzer davon hörten, dass ich der NGWF beigetreten war und meine eigene Gewerkschaft starten wollte, begannen sie mich psychisch unter Druck zu setzen. Es begann damit, dass sie mir zu viel Arbeit gaben, und mir den Lohn kürzten.

Eines Tages rief mich der Qualitätsmanager in sein Büro und drohte mir, dass er mich rauswerfen würde. Er sagte: „Weißt du, wie wir es machen werden? Wir werden Kleidung bringen und die Nähte anschneiden und sagen: Das ist die Qualität, die du produziert hast.“ Sie sagten auch, dass ich mit meiner Gewerkschaftsarbeit aufhören müsse und wenn nicht, dass sie mit der Peinigung und dem Druck weitermachen würden. Sie drohten mir, dass ich nicht mehr dort wohnen könne, wo ich wohnte. Sie drohten, dass sie zu meinem Vermieter gehen würden und ihm sagen würden, er solle mich aus meinem Haus rauswerfen.

Die Besitzer und die anderen höheren Angestellten waren sich noch nicht ganz sicher, ob ich wirklich eine Gewerkschaft gründen würde. Natürlich bestätigte ich ihren Verdacht nicht. Und ich stimmte auch nicht zu, damit aufzuhören. Ich hatte nämlich schon die Unterstützung von 100 Arbeitern für die Gewerkschaft. Ich brauchte nur noch fünfzig mehr, um die 30 Prozent zu erreichen.

Die Fabrik in der ich gearbeitet habe, heißt Elite Garments und der Besitzer hat eine zweite Fabrik, die Excel heißt.

Eines Tages holte mich der Qualitätsmanager ins „Chamber“, den Raum der Vorarbeiter und der anderen höheren Angestellten. Er sagte mir, dass er mich in die andere Fabrik versetzen würde. Ich wollte aber nicht dorthin versetzt werden, weil ich mit der Gründung der Gewerkschaft in meiner Fabrik schon begonnen hatte. All die Arbeit wäre umsonst gewesen.

Es kam soweit, dass der Qualitätsmanager sagte, ich solle darum betteln nicht in die andere Fabrik versetzt zu werden, indem ich seine Füße halte. Drei oder vier Leute waren im gleichen Raum und genossen die Show. Vor ihren Augen hielt ich die Füße des Managers umfasst. Alle machten Fotos. Sie lachten mich aus, kritisierten mich, beschimpften mich. Die Arbeit in der Fabrik ging weiter. Niemand außerhalb des Zimmers wusste, was passiert war. Ich machte das drei Stunden lang. Danach ließen sie mich mit der Warnung gehen, die Gewerkschaft nicht zu gründen.Bis zu diesem Tag wusste sie aber immer noch nicht hundertprozentig, ob ich wirklich eine Gewerkschaft gründen würde.

Nach diesem Vorfall wusste ich natürlich, dass ich nicht die Einzige war, die in der Fabrik litt. Also konnte ich nicht aufhören. Ich hatte schon 100 Leute, die mich unterstützten. Also ging ich vor dem Manager auf die Knie, damit die Gewerkschaft Wirklichkeit werden konnte.

Warum hätte ich aufhören sollen? Ich war schon so weit gekommen.

Später bekam ich die fehlenden 50 Unterschriften. Ich hatte ein Formular, auf dem ich die Unterschriften der ArbeiterInnen sammelte. Das bekam ich von der NGWF. Als ich die 150 Unterschriften hatte, brachte ich das Formular zur NGWF und von dort ging es zur Bestätigung zum Labour Office der Regierung. Als der Qualitätsmanager davon hörte, nahmen die Feindseligkeiten zu. Es gab noch mehr Druck. Man beschimpfte mich bei der Arbeit. Und eines Tages zwangen sie mich, ein weißes Papier zu unterschreiben. So warfen sie mich aus der Fabrik. Ich war arbeitslos.

Aber das Gewerkschafts-Formular war schon eingereicht worden. Darum kamen die Leute vom Labour Office zur Kontrolle in die Fabrik. Sie wollten die Gewerkschaft bestätigen. Von den 150 Unterschriften hatte ich zehn Leute für ein Komitee ausgewählt. Von diesen zehn waren fünf schon gefeuert worden und der Rest hatte zu viel Angst, irgendetwas zu sagen. Sie sprachen nicht. Die Regierungsleute fragten den Qualitätsmanager und den Produktionsmanager, was mit den fünf anderen Arbeitern geschehen war. Sie antworteten, dass die fünf auf eigenen Wunsch gegangen waren. Und die Regierungsleute glaubten ihnen. Sie wusste genau von der NGWF, dass die Arbeiter gefeuert worden waren, aber sie glaubten den Managern. Also wurde die Gewerkschaft bei dieser Kontrolle abgelehnt. Ich glaube, die Leute vom Labour Office unterstützten eher die Fabrikbesitzer als die Gewerkschaften. Man weiß es nicht. Vielleicht wurden sie bestochen?

Jetzt gibt es keine Gewerkschaft in der „Elite Garments“-Fabrik, weil ich dort nicht mehr arbeite. Das alles passierte vor einem Monat. Für den letzten Monat bekam ich keinen Lohn.

Ich hatte in der Textilindustrie zu arbeiten begonnen, weil mein Vater krank wurde. Damals ging ich in die 10. Klasse, zwei Jahre vor dem Abschluss. Er war sehr krank. Also war es an der Zeit für mich, einen Job zu finden. Ohne Abschluss bekam ich keinen guten Job. Ein Nachbar erzählte mir von der Textilfabrik in der Gegend. Also bewarb ich mich dort und bekam den Job. Es war angenehm für mich. Einen besseren Job fand ich nicht.

Als ich arbeitete, verdiente ich 6600 Taka (75€) pro Monat ohne Überstunden und 1500-2000 (ca.22€) für die Überstunden. Ich wohne bei meinen Eltern mit drei Geschwistern. Wir wohnen gemeinsam in diesem Zimmer in Kilga in Dhaka. Wir kochen auf den Gaskochern von den zwei Security Guards, die das Gebäude dort vorne auf der Straße bewachen. Wir teilen die Toilette mit fünf anderen Familien.

Meine drei Schwestern gehen in die Schule. Vorher konnte ich ihre Schulgebühren mit meinem Gehalt zahlen. Das waren pro Monat 2000 Taka. Dieses Zimmer kostet uns 3000 Taka im Monat. Meine Mutter arbeitet als Haushaltshilfe und verdient damit 3500 Taka. Mein Vater kann nicht arbeiten, weil er krank ist. Aber auch als ich noch Arbeit hatte, reichte der Lohn nicht aus, weil ich das ganze Geld für unser Essen, die Miete und die Schulgebühren ausgeben musste. Wenn jemand krank wurde, mussten wir einen Kredit aufnehmen. Es war nie genug.

Meine Mutter ist die einzige, die jetzt Geld verdient. Nachdem ich meinen Job verloren habe, haben wir einen Kredit von 15.000 Taka aufgenommen. In einem halben Jahr muss ich fast 20.000 Taka zurückzahlen.

Die Fabrikbesitzer werden reicher und reicher, aber mit meinem Lohn kam ich nirgendwo hin. Wenn das Gehalt für die Arbeit in der Textilfabrik 15.000 Taka wäre, wenn die Leute diesen Lohn bezahlen könnten, dann könnte ich in Ruhe und befreit leben und wäre nicht immer unter Zeitdruck, um alles zu zahlen.

Ich will nicht mehr in einer Fabrik arbeiten. Ich versuche einen anderen Job zu finden. Wenn das nicht klappt, muss ich doch wieder in einer Fabrik anfangen. Und dann werde ich trotzdem nicht leise sein. Ich muss wieder protestieren. Ich bin so. Als ich von der Gewerkschaft NGWF erfuhr, war ich es, die ihnen Fragen stellte. Es gibt zwei Arten von Menschen: diejenigen, die Korruption sehen und akzeptieren und die anderen, die sie nicht mögen und bekämpfen. Ich gehöre zu Letzteren.

Zuallererst bin ich stolz darauf, Kleidung zu machen, die Menschen überall auf der Welt und im Westen tragen können. Es macht mich stolz, dass entwickelte Länder unsere Kleidung kaufen. Ich bin stolz, dass Du sie trägst.

Gleichzeitig frage ich mich aber auch, warum die westlichen Länder uns keinen anständigen Lohn für unsere Arbeit bezahlen. Warum sie uns nicht unterstützen? Ich will, dass die Zwischenhändler den Fabriken mehr für unsere Kleidung zahlen, damit die Fabrikbesitzer uns ArbeiterInnen besser bezahlen können.

Für Bangladesch ist die Textilindustrie sehr wichtig und mit dieser Industrie können wir die Lage unseres Landes verbessern. Dafür brauchen wir die Hilfe der ausländischen Leute, die unsere Kleidung kaufen. Ich verspreche im Gegenzug, die Kleidung so gut wie möglich zu machen.

Das ist mein Versprechen.

To read the English translation: please see This Is My Promise

You can follow Anna Holl’s Travels to Discover #whomademyclothes on our blog and on Twitterhollanna Anna is reporting in Bangladesh for N21 who have a focus on textile for the next 4 weeks. Http://n21.press/schlagwort/textil/

My name is Arifa Sultana Anny. I am 19 years old. I have worked in the garment industry for two years and six months. A month ago I lost my job because I opened my mouth too wide.

I worked six days a week at the factory. Every day from 8am until 5pm. On most days, I worked overtime from 5pm to 10pm as well. Then I would be in the factory for 14 hours. Sometimes I also had to work on a Friday, so I did not have a day off during the week.

I got up every day at 6am, got ready and did the daily errands. I had to cook and keep the house clean. At 7.40am I went to the factory.

In the factory, it was an ordeal. There were five floors and each floor only had two toilets which were not even clean. 400-500 people were working in the factory. There was no doctor, no canteen and no prayer room. We supplied clothes to brands such as ZeroXposur (American outdoor brand) and Li and Fung (a $20 billion global sourcing firm that supplies 40% of all apparel sold in the US). I was working on the production of jackets and my job was a Checker. After the jackets had been sewn, it was my task to check for errors. If I found a mistake, I went to the person who had worked on that stage of the garment so that they could correct the mistake. For this job I got paid less than the seamstresses.

I was constantly put under pressure

If I overlooked a mistake and the line managers discovered it, they would tell me that I’m not doing my job well. If the line managers found a mistake, they made me suffer. They docked hours from my attendance record for which I was not paid, even though I had worked.

One day I heard about the National Garment Workers Federation (NGWF) and through them I learned about labour unions. So I wanted to form a labour union in my factory. To do this, you need the support of 30% of the workers.

When I raised the subject for the first time and my colleagues heard that I wanted to start a union, they initially feared threats from their manager and were afraid of losing their jobs. I worked every day. I spoke to the other workers during their lunch hour, after work and in their homes. And sometimes the workers said “no” so I explained to them again why we needed to form a labour union and often that no became a yes.

When the factory owners heard that I had joined the NGWF and wanted to start my own union, they began to put me under psychological pressure. It started with them giving me too much work and then sometimes they docked my wage.

One day I received a message to see the Quality Manager in his office who threatened to throw me out.

He said: Do you know how we will do it? We will bring clothes and cut the seams and say this is the quality that you have produced.

They said that I had to give up on the idea of a union and, if not, they would carry on with the torture and pressure. They threatened that I could no longer live in my home. They threatened to go to my landlord and tell him to throw me out.

The owners and other senior staff were not quite sure if I would really form a union. Of course, I did not confirm their suspicions. But I did not agree to stop it. I had the support of 100 workers for the union. I needed only fifty more to reach the required 30%.

The factory where I worked was called Elite Garments and the owner has a second factory called Excel.

One day the Quality Manager took me into the “Chamber” the room of the foreman and other senior managers. He told me that he would relocate me to the other factory. However, I did not want to be relocated because I had already started establishing the union within my factory. All the work would have been in vain.

It came to a point where the Quality Manager said I should beg before his feet not to be transferred. Three or four people were in the same room and enjoyed the show. Before their eyes, I went on my knees and held the feet of the manager. They all took pictures. They laughed at me, criticised me, insulted me. The work in the factory went on. No one outside the room knew what had happened. I did that for three hours. Then they let me go with a warning not to start the union. However, up until this point they still did not know one hundred percent if I would really form a union.

After this incident I knew, of course, that I was not the only one who suffered in the factory. So I could not stop. I had 100 people who supported me. I had begged on my knees to the manager so that the union could become a reality.

Why should I give up after I had come this far?

Later I got the missing 50 signatures. I had a form on which I collected the signatures of the workers which I got from the NGWF. When I had the 150 signatures, I brought the form to the NGWF and from there it went for confirmation to the Labour Office of the Government. When the Quality Manager heard about it the hostility increased. There was even more pressure. They insulted me at work. Then one day they took me by force to sign on a sheet of white paper. Then they threw me out of the factory. I was unemployed.

But the form to set up a labour union was already submitted. That is why people from the Labour Office came to the factory; they wanted to confirm the union. Of the 150 signatures, I had selected ten people for a committee. Five of the ten had already been fired and the rest were too scared to say anything. They did not speak. The government representatives asked the Quality Manager and the Production Manager what had happened to the five workers. They replied that the five had left of their own accord. And the government represenatives believed them. They knew from the NGWF that the workers had been fired, but they decided to believe the managers, and so the union was rejected. It seems the people from the Labour Office support factory owners rather than labour unions. We do not know, maybe they were bribed.

Now there is no trade union at the Elite factory because I no longer work there. This all happened a month ago. For the last month, I have received no income.

I had begun to work in the textile industry because my father was ill. When I entered 10th grade, two years before graduation, he became very ill, so it was time for me to find a job. Obviously I did not get a good job. A neighbour told me about a textile factory in the area, so I applied there and I got the job. It was ok for me. I didn’t find a better job.

When I worked, I earned 6600 Taka (75 € or £55) excluding overtime and from 1500 to 2000 (about 22 € or £16) for the overtime. I live with my parents and my three siblings. We live together in one room in Kilga, Dhaka. We cook on the gas stoves of two security guards who guard the building across the street. We share the toilet with five other families.

My three sisters go to school. Before I could pay their school fees with my salary – that was 2000 taka per month (22 € or £16). This room cost us 3,000 taka (33 € or £25) a month. My mother works as a maid and earns 3,500 taka (40€ or £29). My father can not work because he is ill. Even when I was working, the salary was not enough because I had to spend all the money on food, rent and school fees. If someone got sick, we had to take out a loan. It was never enough.

My mother is the only person who earns money now. After I lost my job, we had taken out a loan of 15000 taka (170€ or £125). In six months, I have to pay back nearly 20000 Taka (€227 or £167).

The factory owners become richer and richer, but with my salary I was not going anywhere. If I could earn 15000 taka (170€ or £125) a month for working in a garment factory, then I could live in peace and would not always be under pressure to pay bills.

I do not want to work in a factory. I’m trying to find another job but otherwise I will have to start working in a factory again. And I will still not be quiet. I must protest again. I am that kind of person. When I learned about the NGWF, I was the one who asked them questions. There are two kinds of people: those who see and accept corruption and the others who do not like it and fight it. I belong to the latter group.

I am proud to make clothes that people can wear anywhere in the world and in the West. It makes me proud that developed countries buy our clothes. I am so proud that you wear them.

At the same time, I also wonder why the Western countries do not pay us a decent wage for our work? Why don’t they support us? I want the middlemen to pay more to the factory for our clothes so the factory owners can pay more to the workers.

In Bangladesh, the textile industry is very important and with this industry we can improve the situation in our country. For this to happen, we need the help of the foreign people who buy our clothes. In return, I promise to make your clothes to the highest possible standard.

This is my promise.

You can follow Anna Holl’s travels to discover #whomademyclothes on our blog and on Twitter @hollanna Anna is reporting in Bangladesh for N21 who have a focus on textiles for the next 4 weeks. http://n21.press/schlagwort/textil/

Currently, markets are dominated by a Fast Fashion model that creates waste and often mistreats human beings in the drive for cheap, disposable clothing. Tripty began with inspiration to take the heritage and skill of Bangladesh and change that model.

We wanted to create a fashion brand that benefits communities, culture and environment and rethinks the way international products are created in developing countries. By combining traditional weaving, stitching and dyeing techniques with innovative and sustainable materials such as pineapple fiber it is possible to create products that are both relevant and timeless. An ethical supply chain is within reach.

The Tripty Project is a Slow Fashion brand based in Bangladesh and Oakland, CA. You can support The Tripty Project’s Kickstarter Campaign here

Find out more about The Tripty Project through their Facebook, Instagram and Twitter accounts.

Tesco may not be the first brand that comes to mind when you consider ethical trading. However their F&F clothing range aims to deliver “great products at great prices from factories that (they) are proud of”, and they claim that they ‘want to be a force for change in both reducing our social and environmental impact’. But when a your child’s school polo shirt costs just £2.50 for 2, you do wonder what corners are cut to achieve the incredibly low price.

Since the tragedy of the Rana Plaza, working conditions in Bangladesh’s clothing factories have been put under scrutiny. We, the consumers, have been forced to consider #whomademyclothes? Tesco’s shiny corporate website naturally says all the things that we want to hear. So, in an attempt to dig deeper and find out what Tesco is actually doing, I spoke to Dani Baker, Corporate Responsibility Manager of F&F here in the UK, and Mashuda Begum, Senior Manager of Responsible Sourcing, working on the ground in Bangladesh.

Q: What practical steps is Tesco taking to improve working conditions in Bangladesh? Dani: We are committed to ensure that anyone who supplies any products to F&F has the best possible condition for their workers. We understand that this cannot be done from afar, but by working in direct partnership with all our suppliers, which is why we have people around the world working on the ground. In Bangladesh we have a team of about 60 people who not only check things like the fire and safety standards of factories, but also make sure that corners are not cut. So that the factories are a good place to be with staff being paid a decent wage, on time and wider social economic issues are being addressed – like ensuring that their children can go to school.

We have also been proud to support a number of initiatives, including programmes like the Benefits for Business and Working (BBW) training, run by Impactt, since 2010. Through this scheme, we have seen real improvements in factories as they have looked at ways to not only to improve the efficiency of the production line and the quality of the work, but also at human resources, communication and worker welfare. The results have been amazing in providing workers with reduced hours, better pay and benefits. Another project, Phulki, is a women’s empowerment scheme which provides crèches for female workers so they have somewhere safe to leave their children whilst they work- helping to protect them from the possible dangers of drowning, sexual abuse or even trafficking.

All of the factories we use have regular independent audits. We don’t just take the audit results at face value, our team on the ground ensure a more long-term collaborative approach; this includes a number of interventions such as running interactive workshops with our factories, so we can work with them on problems that arise, and support them running their factory safely and legally.

Q: That’s great that Tesco is regularly in the factories. But, how do you know that what they show you truly reflects everyday practice? Dani: This is why it is important to us that we build up long-term collaborative partnerships with our suppliers, so we can have a real insight into their everyday practices. The majority of the factories we use, we have worked with for over five years. However, the product is also a good indicator as to whether everything is OK in the factories. We regularly check the quality and if there are any persistent issues, this tends to flag up that there may be a problem.

Q: Your website states that your team in Bangladesh are there to ‘build relationships and to ensure decent working standards.’ But what does that mean in practice? Mashuda: It means providing a safe and hygienic working environment where adequate steps have been taken to prevent fire related, machine and safety accidents. Workers receive regular and recorded health and safety training, and this training will be repeated for new or reassigned workers. We also mandate that workers should have access to clean toilet facilities and to potable water, and, if appropriate, sanitary facilities for food storage shall be provided. Accommodation, where provided, should be clean, safe, and meet the basic needs of the workers.

Q: What are some of the challenges of implementing this in Bangladesh? Dani:Hartals occur relatively regularly and sometimes are violent; roads are often blocked off which can mean that certain parts of the capital can get cut off. This is difficult not just for F&F and our employees in Dhaka, but also for the factories. Products and materials that need to be received by the factories in order for their workforce to make an order can be delayed. The workforce whose role it is to make the product could be sitting and waiting for deliveries to arrive for days and this can ultimately lead to longer working days, when they finally arrive. Factory training programmes, meetings and visits – no matter how important – must be put on hold and rescheduled.

We have also be working to help some factory owners understand that cutting corners doesn’t make sense in the long run. The short term gain of not providing workers with basic safety equipment is likely to have a long-term detrimental effect on their business and workers and just doesn’t make sense. It has also been a challenge for them to see us and the BBW as part of the process and fellow collaborators and not just seen as external people in their factory. In some cases it has been a more effective process to empower the workforce to initiate change with some factory owners.

Q: As documented in The True Cost movie, there is clearly an issue in Bangladesh of workers not having the right to collective bargaining with factory owners. How does Tesco use their influence on factory owners to persuade them it is worth their while improving conditions for the workers? Mashuda: Tesco requires that all factories that we use in Bangladesh must have a Workers Participatory Committee formed through an election process, to ensure the workers’ rights and benefits. During our regular audits we monitor whether this has been in place and it is viewed as a violation of law if the factory doesn’t comply, which we follow up until this criteria has been met.

Q: What social enterprise work are you doing in Bangladesh? Dani: Studies have shown that children, in the developing world, who go to school in uniform perform better in tests and have lower rates of absenteeism. This year we are donating 20,000 school uniforms in Bangladesh as part of our Buy One, Give One scheme. When a customer buys an item from the Buy One, Give One range we will donate an entire uniform. So as our polo shirts are made in Bangladesh for every pack bought we donate a uniform to a child there.

Please click here for more information.

Tesco Clothing Corporate Responsibility

The True Cost Movie – www.truecostmovie.com

#whomademyclothes? – www.fashionrevolution.org

Project BBW – www.impacttlimited.com

All photos used with permission of Tesco.

Blog kindly reproduced with permission from N4Mummy