Based in Los Angeles, Osei-Duro’s rich identity is strongly linked to Ghana and its textile history. We caught up with its co-founder Maryanne Mathias to discuss the challenges of building a sustainable value chain in Ghana while reviving crafts and building on existing skills.

What led you to create an ethical fashion brand in Ghana?

I studied fashion design in Vancouver, Canada and had a small hand dyed clothing line based out of Montreal. At that time I was designing, sewing, and dyeing all the clothing on my own. After a certain time I grew frustrated with the clothing industry and decided to leave it and travel the world. Inspired by the textiles in the countries I visited, I ended up designing capsule collections in Ghana, Morocco, Egypt and India. Ghana was the first country I visited, and it drew me because of its rich cottage textile industry that had so much opportunity for growth and development. It is also English speaking and has a relatively stable economy, and is peaceful.

Tell us more about your background.

I attended the Vancouver Waldorf School (from Kindergarten to 12th grade) where the focus was on “learning with the head, heart, and hands”. We did a lot of handicrafts like natural dying, knitting, weaving, woodwork, and ceramics, so I formed a solid foundation in artisan work. I then went on to study Fashion Design and Technology and formed my first company in my sophomore year.

Which materials do you use for your clothing? Where do you source them and are they sustainable?

We mostly use silk, rayon, and cotton. We source our cotton from Ghana, but since the cotton mill closed down, we are looking for an ethical international supplier. Our silk and rayon come from India and China. It is our goal to insure all our fabrics are made in audited factories, but we have limited resources and can only focus on one thing at a time.

Do you work with chemical or organic dyes?

We work with both chemical and organic dyes as they do different things. However we are super excited about developing more organic dyes to use in our upcoming collections. Currently we use indigo from the north of Ghana, and onion skins leftover from roadside restaurants and the vegetable market. We introduce a new natural dye every season and for AW17 we are using cutch, it has the most amazing army green colour on silk.

How do you decide which material is best for a collection?

Based on what we are trying achieve in a particular garment.

You recently expanded your production to Peru, tell us more about that. What was missing in Ghana?

Our main focus is to develop the export garment industry in Ghana. But we need our sales to be strong in order to achieve this. By adding warm alpaca sweaters we were able to increase sales for the fall/winter seasons, which then helped us keep our batikers, weavers, dyers and sewers in Ghana working.

What are your thoughts on mass production of fashion in Asia?

We try to support a fashion industry where people are able to buy less items, but of better quality and more integrity.

How would you describe your collections?

Our collections generally include a range of hand dyed wax resist batik prints, hand-woven cottons from the north of Ghana, hand-dyed natural indigo, and cotton or alpaca sweaters from Peru. We also use block printing from India, and are excited to bring the technique to Ghana soon.

What are the challenges you have come up against in your journey in running an ethical clothing brand in Ghana?

Getting consistent quality from our artisans and sewers.

What contribution do you hope to make in the ethical fashion ecosystem in Ghana?

We want to build the ethical fashion garment industry in Ghana. As it is we were the first brand to do batik on silk and rayon, and now there are a bunch of other companies doing it. So that’s a win. If more companies see what we are doing and come to Ghana to expand, then we are contributing.

What are your plans for the future?

Next up is expanding our natural dye library and workshop, and working much more with the weavers.

Any exciting news you would love to share about Osei-Duro?

We are super excited about our Spring/Summer 2017 collection and photoshoot, shot on location in Accra. Photos to come!

Photos – Courtesy of Osei-Duro

Os chamados “contentores de reciclagem de roupa” podem parecer à partida uma ideia genial, mas escondem uma realidade muito mais complexa e nociva para países subdesenvolvidos.

Reciclar é bom e reutilizar é bom, mas no que toca a roupa, a quantidade que consumimos (e consequentemente doamos) é tanta, que é impossível ser escoada em Portugal. O problema está no consumo desmedido! Uma das maiores ONGs que opera no ramo recolheu só em 2015 mais de 5 mil toneladas de roupa doada. É verdade: A oferta é esmagadoramente maior que a procura!

O que geralmente acontece é que a roupa que é doada por si é recolhida a custo zero e revendida com margens de lucro em lojas de segunda mão. Este lucro é só depois aplicado em missões humanitárias, mas na realidade só cerca de 10% da roupa fica por terras lusas. Os restantes 90% são empacotados e enviados em contentores para países subdesenvolvidos em África, Europa de Leste e Sul da Ásia, onde são posteriormente vendidos nos mercados a preços tão baixos, que têm vindo a destruir a indústria têxtil local, apesar dos consecutivos esforços dos respetivos governos em subsidiar as fábricas para desenvolverem uma economia independente e livre da dívida do Ocidente. Nos últimos 30 anos, o Gana – o maior recetor de re-wear do mundo – viu a sua atividade reduzida de 40 fábricas para apenas 1; e no Zâmbia, o produtor de algodão passou a ter poder de compra só para roupa em segunda mão, e não para o seu próprio produto.

Ou seja: Ironicamente, estas roupas são feitas por comunidades pobres do terceiro mundo, para o consumidor ocidental as usar durante poucos meses, e as doar para organizações que as vendem de novo para o terceiro mundo, graças ao comércio livre que lhes mata a produção local e aprisiona a sua economia ao Ocidente.

Para além de Portugal, esta realidade acontece em muitos outros países da Europa, EUA, Japão e Canadá.

Já em relação à reciclagem – que em Portugal tem pouca expressão – muito pouco do que vem dos contentores é realmente reciclado, e quando o é, raramente é para voltar a fazer fio. Desengane-se quem pensa que de uma T-shirt doada, se faz outra nova e imaculada. A tecnologia vigente permite reciclar uma fibra só de cada vez (uma camisa 100% algodão, por exemplo, o que é raro!), sendo que todos os fios mistos (algodão-poliéster ou lã-acrílico, por exemplo) têm de passar por um processo químico pouco amigo do ambiente para suprimir uma das fibras. Ainda assim, o fio reciclado é pouco resistente e de fraca qualidade. O nosso sector da reciclagem está muito focado na trituração dos resíduos têxteis para a produção de colchões, indústria automóvel e panos de desperdício.

Já em relação à reciclagem – que em Portugal tem pouca expressão – muito pouco do que vem dos contentores é realmente reciclado, e quando o é, raramente é para voltar a fazer fio. Desengane-se quem pensa que de uma T-shirt doada, se faz outra nova e imaculada. A tecnologia vigente permite reciclar uma fibra só de cada vez (uma camisa 100% algodão, por exemplo, o que é raro!), sendo que todos os fios mistos (algodão-poliéster ou lã-acrílico, por exemplo) têm de passar por um processo químico pouco amigo do ambiente para suprimir uma das fibras. Ainda assim, o fio reciclado é pouco resistente e de fraca qualidade. O nosso sector da reciclagem está muito focado na trituração dos resíduos têxteis para a produção de colchões, indústria automóvel e panos de desperdício.

Ora bem, já sabemos que Portugal fica limpinho de resíduos têxteis. Mas, e no outro lado do mundo? Continuamos a ter a nossa quota-parte de responsabilidade enquanto consumidores, enquanto empresas que induzimos ao consumo desmensurado.

Aconselhamos a todos os consumidores a pensar 2 vezes sobre a estratégia de marketing da Inditex (Zara, Pull & Bear, Stradivarius, Bershka, Oysho, Massimo Dutti e outros) que por um lado lava a cara, mostrando-se falaciosamente “eco” aos olhos do seu consumidor, e por outro põe-se a jeito para induzir a um consumo ainda maior, estando já ali ao lado a vender produtos novos. Consumo este, que é na realidade a grande raiz deste problema! Mas que quanto maior for, mais convém à Inditex.

No fundo, é uma tática fácil! Será como dizer ao consumidor: – Anda! Eu ajudo-te a esvaziar o teu roupeiro, para poderes comprar mais, de consciência leve!

Pense primeiro:

– Preciso mesmo de roupa nova?

– Se preciso mesmo de roupa nova, posso reformar a que tenho ou trocar com alguém?

– Se não, posso comprar em segunda mão?

– Se não, posso fazer num(a) costureiro(a), ou comprar numa marca de comércio-justo?

Obrigada por ser curioso, questionar, e agir!

A equipa Fashion Revolution Portugal

Questione em portugalfashionrevolution.org

Fontes: Al Jazeera, Independent, BBC, The Guardian, Expresso, RTP, INE

Fotos: Colin Crowley, 7/3/2009 (cabeçalho) e Cora Went, 26/10/2010

Notes on the health of the fashion industry, and some ideas of what I would like to highlight in my next collection…

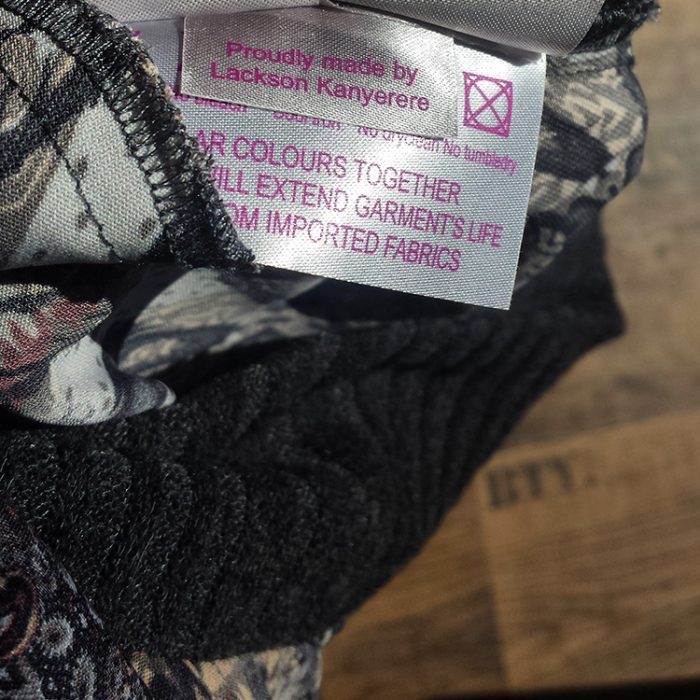

One of the key elements of the creation process is the talented machinists and other crafters that help to construct the garments we design. It is a symbiotic partnership where one cannot function without the other. The exploitation of workers in the garment industry has been a hot topic in social media generating massive momentum with the hashtags #whomademyclothes and #fashrev along with the proudly South African #lovezabuyza. Documentaries made after the Rana Plaza collapse, such as The True Cost have also highlighted the plight of workers in the garment manufacturing industry

In a recently published paper concerning transparency in the fashion industry titled It’s Time for a Fashion Revolution the following interesting points were made.

– The current fashion business model is broken and operates in a fundamentally unsustainable way…we cannot keep chasing the cheapest labour and natural resources. Eventually, they will run out.

– 36 million people are working as modern day slaves, many of them producing clothing for western brands.

– They touch on the topic of paying a living wage rather than the bare minimum wage which in many eastern countries covers only 60% of the cost of living in a slum. Waste is also an intricate part of how the fashion industry currently operates with huge amounts of fabric and clothing ending up in landfills. Clothing donated to charities in Western countries end up being dumped on or sold in third world countries killing any chance of developing sustainable fashion industries in these countries.

WE ARE THE FASHION REVOLUTION

Our main focus is to change the narrative surrounding fashion; to transform it into a force for good. We believe that it is everybody’s responsibility; not just the fashion designers, buyers and big retailer, but also the end consumer, who allows this state of affairs to continue by purchasing the “poly-blend T-shirts and runway rip offs”

Highlighting WHERE and by WHOM clothing is made is an integral part of the Fashion revolution’s mantra, telling the stories behind the clothing. Transparently is key to insure that consumers don’t unknowingly aid and abet dubious practices “and contribute to a future that is bad for people and the planet”

WE BELIEVE IN A FASHION INDUSTRY THAT VALUES PEOPLE, THE ENVIRONMENT, CREATIVITY AND PROFIT IN EQUAL MEASURE

As a fairly well established designer in the South African fashion industry I feel that it is my duty and privilege to help spread the message. I have always believed in creating sustainable jobs especially in the labour intensive clothing industry and thus I’ve kind of approached the topic back to front.

In a recent “Eureka!” moment I realised that being an ethical designer does not end with paying a fair wage, crediting all input in design and well as production and insuring that as little as possible waste that we generate ends up in landfills. I need to tell people; consumers, fellow designers and other members of this huge industry, what I’m up to.

The main reasoning behind it is so that my loyal and amazing customers know what they are buying and why they are paying more for my clothing than mass produced runway-ripoffs. I want them to share in the feel good glow; contributing, in whatever manner, to creating more a sustainable industry. I want this ethos to rub off on my fellow designers, most of who are already ticking all the #fashrev boxes, and inspire them to talk about what they are doing.

By adding more voices to the movement and using any available platform to broadcast it the Fashion Revolution will happen. We have committed 30 years of fast fashion atrocities and created an unsustainable monstrous industry that generates trillions of dollars annually yet fails to honour its most key member.

AFRICAN HANDS CREATING CLOTHING FOR AFRICAN BODIES

South Africa sits at the tip of a culturally rich continent with access to a huge pool of talented craftsmen and -women. Before the rise of the industrial Far East we used to boast many successful fabric mills and production houses. Our bodies do not fit the Chinese, European or American mould and we have been forced to feel shame rather than celebrate being healthy human beings. Our sense of style and ethnic signatures has been appropriated the world over, yet we still flock to support cheap, badly made Western fast fashion.

We need to change our own narrative and stop allowing ourselves to be exploited. We have the power to unite the local fashion industry and ignite a revolution to radically change the way we think about clothing.

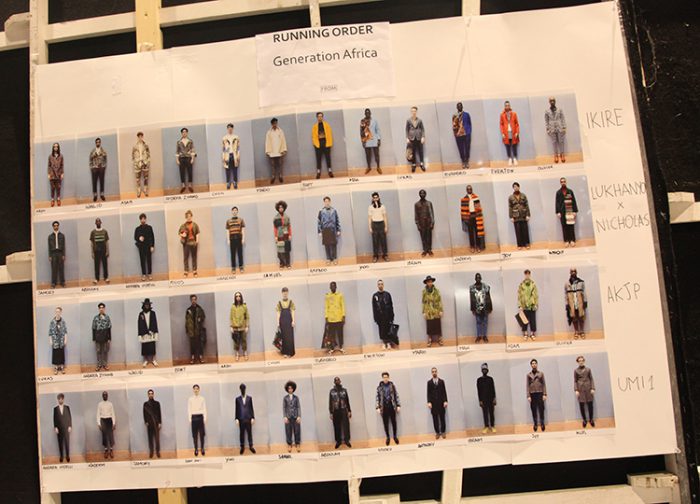

Yesterday at Pitti Immagine Uomo 89 in Florence, the Fondazione Pitti Discovery and ITC Ethical Fashion Initiative held a runway show “Generation Africa”. With a focus on fashion from Africa, this unique platform promoted young and talented fashion designers from the continent, and showed the energy of today’s African creative scene.

“Generation Africa is the chance to open a new window on one of today‘s most creative scenes” says Lapo Cianchi, head of Special Projects at Pitti Immagine

The show featured four brands already known on the international market that present different facets of the African continent and who focus on manufacturing in their home countries. AKJP, Ikiré Jones, Lukhanyo Mdinigi x Nicholas Coutts and U.Mi-1 all presented their Autumn/Winter 2016-17 men’s collections.

“We continue our collaboration with Pitti Immagine to showcase the creativity of Africa. We want to convey a different image of the continent, one of innovation and diversity with a strong youthful energy for positive change. Pitti Uomo is the perfect platform for the designers to express their vision and show that Africa means serious business.” says Simone Cipriani, Head and Founder of the ITC Ethical Fashion Initiative.

For Generation Africa, the Ethical Fashion Initiative partnered with the Italian association, Lai-momo which welcomes asylum-seekers in Italy and promotes cross-cultural exchanges between Africa and Europe with the aim of reducing stereotypes and preconceptions. As part of a joint effort by EFI, Lai-momo and Pitti Immagine to raise awareness on migration, three asylum seekers modelled for the show, giving them an opportunity to earn a wage and be part of an empowering international event celebrating creativity from Africa. Continuously striving to improve diversity in the fashion industry, the Ethical Fashion Initiative aims to demonstrate fashion’s capacity to support the betterment of society.

The Ethical Fashion Initiative is a flagship programme of the International Trade Centre, a joint agency of the United Nations and the World Trade Organization. The Ethical Fashion Initiative links the world’s top fashion talents to marginalised artisans – the majority of them women – in East and West Africa, Haiti and the West Bank. The Initiative has been connecting artisans to the global fashion supply chain since 2009. The Ethical Fashion Initiative also works with the rising generation of fashion talent from Africa, encouraging the forging of fulfilling creative collaborations with artisans on the continent. Under its slogan, “Not Charity, Just Work” the Ethical Fashion Initiative advocates a fairer global fashion industry.

The four participating brands were:

AKJP // Keith Henning & Jody Paulsen, South Africa

AKJP (Adriaan Kuiters + Jody Paulsen) is a menswear and womenswear brand founded by South African designer duo, Keith Henning and Jody Paulsen. AKJP‘s signature is its artful contemporary twist on classic and utilitarian menswear. The development of strong prints and sports-inspired motifs for each collection has become core to AKJP. AKJP uses layering, boxy silhouettes and asymmetrical detailing as a signature styling feature. AKJP has been recognised as one of South Africa’s most innovative brands, bringing contemporary and cool to the South African fashion landscape. In 2015, AKJP was one of the finalists at Vogue Italia’s Who Is On Next? Dubai.

IKIRÉ JONES // Walé Oyéjidé, USA & Nigeria

Ikiré Jones (pronounced “E-kee-rae Jones”) is a menswear company that marries African aesthetics with classic art from all over the world. Each of the brand’s pieces tells a contemporary story by using historical artwork as a medium for modern expression. With every collection, the brand places a strong emphasis on societal issues that affect immigrant and transient populations across the globe. Importantly, Ikiré Jones seeks to properly introduce modern African culture to the world. Through clothing, Ikiré Jones seeks to weave together a tighter global community. The brand’s tailoring is done in the United States, and its accessories are printed and hand-rolled in Macclesfield, United Kingdom.

LUKHANYO MDINGI x NICHOLAS COUTTS // Lukhanyo Mdingi & Nicholas Coutts, South Africa

South African designers Lukhanyo Mdingi and Nicholas Coutts collaborate on this Autumn/Winter 2016-17 collection to illuminate each other’s aesthetics. The design partnership combines Mdingi’s minimalist approach with Coutts’ distinctive signature weaving style. Together, the designers create a menswear collection that embodies strength, empowerment and contemporary sophistication.

Lukhanyo Mdingi interprets minimal aesthetics with his clothing, finding the balance between line, form and texture. Mdingi creates minimal looks that are distinct and powerful, with a flare of contemporary elegance and sophistication. Nicholas Coutts’ signature is creating garments that are textured and uses fabrication to create a pleasing contrasting visual. Influenced by the Arts & Crafts movement, Coutts specialises in using handwoven fabrics and hand knitted items.

U.Mi-1 // Gozi Ochonogor, Nigeria & UK

U.Mi-1 (pronounced you.me.one) is a contemporary brand for the modern cool man. It tells a different side of the African fashion story with collections inspired by Nigerian culture, architecture and art. Headed by Nigerian designer Gozi Ochonogor who calls London, Tokyo and Lagos her homes, U.Mi-1 collections are a blend of British tailoring aesthetic with the hallmark of Japanese artisanship and African spirit, delivering innovative designs and quality. Best described as tailoring with a twist, U.Mi-1 focuses on style, comfort and quality with interesting detailing that the wearer discovers anew.

The Beat of Africa hit Milan fashion week for the third time as Biffi Boutique and ITC Ethical Fashion Initiative collaborated to bring African fashion talent to the Italian fashion capital. The weeklong designer showcase launched for Vogue Fashion’s Night Out.

Biffi Boutique is one of Milan’s legendary fashion stores, owned by Rosy Biffi. The Milanese boutique located in Corso Genova displayed the Spring/Summer 2016 womenswear looks of four designers selected by the Ethical Fashion Initiative: MaXhosa by Laduma (South Africa), Mimi Plange (US-Ghana), Sindiso Khumalo (South Africa) and Sophie Zinga (Senegal). MaXhosa by Laduma will also show some menswear looks.

The Ethical Fashion Initiative is a flagship programme of the International Trade Centre, a joint agency of the United Nations and the World Trade Organization. The Ethical Fashion Initiative works with the rising generation of fashion talent from Africa, encouraging the forging of fulfilling creative collaborations with artisans on the continent. The Ethical Fashion Initiative also enables artisans living in urban and rural poverty to connect with the global fashion chain. Under its slogan, “NOT CHARITY, JUST WORK.” the Ethical Fashion Initiative advocates a fairer global fashion industry.

Simone Cipriani, founder and head of the Ethical Fashion Initiative, said:

“There is a mountain of talent in Africa. When I was young, Italy was about creativity and artisans. Today Africa is the same.”

DESIGNERS

MaXhosa by Laduma

MaXhosa by Laduma is a South African knitwear brand founded in 2010 by Laduma Ngxokolo. The South African Xhosa manhood initiation ritual practiced by amakrwala was behind the launch of the brand as Laduma sought to create Xhosa-inspired modern knitwear that would be suitable for this tradition. Since, the Xhosa aesthetic has come to be part of the DNA of the knitwear brand as Laduma has explored and reinterpreted traditional Xhosa beadwork, patterns, symbolism and colours to inspire his modern knitwear line. Through his work, Laduma is an agent of change, shifting and evolving with the changing times and further engaging in the dialogue that keeps pushing traditional culture toward the future.

Mimi Plange

Mimi Plange is a modern womenswear brand launched in 2010 by American-Ghanaian designer, Mimi Plange. Lost African civilizations inspire the Mimi Plange clothing and gives the collection a depth of meaning. High quality craftsmanship is reflected in each Mimi Plange piece and the brand prides itself on making well-constructed and fitted clothing. The Mimi Plange woman moves in international circles and is successful, cultured and conscientious. Mimi Plange says “I design clothes for a woman who wears what suits her. She has nothing to prove.” Mimi Plange’s designs have gained the seal of approval from American first-lady Michelle Obama, pop-queen Rihanna and tennis star, Serena Williams.

Sindiso Khumalo

Based between London and Cape Town, Sindiso Khumalo launched her eponymous label after being a finalist in the Elle New Talent competition. The strong and complex graphic prints used by Sindiso have become the signature of her collections. With a background in textile design, the designer has developed her label with a focus on modern sustainable textiles and works with several NGO’s in South Africa to develop sustainable textiles. In 2013, Sindiso Khumalo was nominated for the “Most Beautiful Object in South Africa” Award by the Design Indaba. Her work has been showcased at the Royal Festival Hall in London and the Smithsonian Museum of African Art in Washington. Sindiso studied architecture at the University of Cape Town and Design for Textile Futures at Central St Martins.

Sophie Zinga

As an avid art enthusiast, Senegalese born Sophie Nzinga Sy pursued her creative talent at Parsons School of Design. This led Sophie to set up her own brand: Sophie Zinga. Her brand is strongly influenced by her travels and the fusion of multiple cultures – specifically Sophie’s African roots and her New York City education and entrepreneurial mindset. Quality is a keystone of the Sophie Zinga brand, which uses the finest materials and fabrics (silk, satin, bazin, semi-precious stones etc.) Sophie’s design philosophy is to give the modern woman the key pieces to constantly re-invent her style while exuding confidence whether she is in a board meeting, attending a gala or traveling between New York and Lagos. The Sophie Zinga woman is socially conscious, well-travelled and is part of today’s cosmopolitan world.

#beatofafrica2015

Ethical Fashion Initiative is a flagship programme of the International Trade Centre, a joint agency of the United Nations and the World Trade Organization. The Initiative links the world’s top fashion talents to marginalised artisans – the majority of them women – in East and West Africa, Haiti and the West Bank. Active since 2009, the Initiative enables artisans living in urban and rural poverty to connect with the global fashion chain. The Ethical Fashion Initiative also enables Africa’s rising generation of fashion talent to forge environmentally sound, sustainable and fulfilling creative collaborations with local artisans.Under its slogan, “NOT CHARITY, JUST WORK.” the Ethical Fashion Initiative advocates a fairer global fashion industry.

Over the past few seasons the Fondazione Pitti Discovery has been setting aside a special area for the rising stars on the world’s economic and creative stage with the Guest Nation project. This edition, in cooperation with the ITCEthical Fashion Initiative, focussed on fashion from Africa with a special event “Constellation Africa”, to promote young and talented designers from the continent.

“I believe that Pitti Uomo is the best platform to showcase these innovative designers from Africa, the continent which hosts the future of fashion and couture“, says Simone Cipriani, Head and Founder of the ITC Ethical Fashion Initiative. “The richness of materials and the beauty of their designs are truly unique. This is where our global society is going: interconnectedness. Global and local dimensions brought together through fashion“.

The four participating brands were:

ORANGE CULTURE // Adebayo Oke-Lawal from Nigeria

Orange Culture is a contemporary menswear brand created by Nigerian designer Adebayo OkeLawal in 2011. The brand combines classic and contemporary western silhouettes with an African edge. Orange Culture fuses Nigerian silhouettes, print fabrics and contemporary urban streetwear. Orange Culture is more than a clothing line, it is a “movement” for a creative class of men that are “self-aware, expressive, explorative and art-loving nomads”. Orange culture has been featured by top fashion magazines and was recently shortlisted by Vogue Talents for Africa and LVMH’s 2014 Young Fashion Designer Prize.

MaXhosa by Laduma // Laduma Ngxokolo from South Africa

MaXhosa by Laduma is a South African knitwear brand founded in 2010 by Laduma Ngxokolo. The South African Xhosa manhood initiation ritual practiced by amakrwala was behind the launch of the brand as Laduma sought to create Xhosa-inspired modern knitwear that would be suitable for this tradition. Since, the Xhosa aesthetic has come to be part of the DNA of the knitwear brand as Laduma has explored and reinterpreted traditional Xhosa beadwork, patterns, symbolism and colours to inspire his modern knitwear line. Through his work, Laduma is an agent of change, shifting and evolving with the changing times and further engaging in the dialogue that keeps pushing traditional culture toward the future.

PROJECTO MENTAL // Tekasala Ma’at Nzinga & Shunnoz Fiel from Angola

Projecto Mental is an Angolan fashion brand, founded in 2004 by creative duo Shunnoz Fiel & Tekasala Ma’at Nzinga, which fuses fashion and art. The brand was created in the aftermath of the civil war as a platform to help reshape Angola’s cultural identity, after the country was ravaged by decades of civil war. Suits with an experimental twist are the signature item of the Projecto Mental brand. Projecto Mental takes an avant-garde approach to tailoring as the designers re-imagine and re-invent the traditional suit for men and women. Strong block colours combined with prints & patterns bring boldness to each design.

DENT DE MAN // Alexis Temomanin from Ivory Coast & UK

Dent de Man is a menswear brand created in 2012 by British-Ivorian designer, Alexis Temomanin. Dent de Man’s approach to luxury style is defined by a mix of classic tailoring with colourful patterned fabric. The Dent de Man lifestyle is defined by freedom, quality and “esthétisme”, empowering individuals to dress for themselves. Self-expression is core to Dent de Man’s philosophy. The brand prides itself on the use of vintage fabrics and celebration of ancient printing techniques, Dent de Man adapts decadent and bold Java prints forming unique garments that allow individuals to own distinctive and irreplaceable pieces. All Dent de Man fabric is carefully sourced and possesses its own story and meaning.

Margaret Mschai, a mother of two, makes her living by completing various tasks at the Wildlife Works eco-clothing factory, and is wholly grateful for it. Her tasks include trimming, folding and packaging the fabric and finished clothes.

“I love what I do mostly because it is an important part in the chain of events that creates unique outfits for export,” she says, adding, “We cannot all be machinists or designers. Someone has to trim the loose threads and fold the clothes so that they are presented neatly for the final consumer.”

As Margaret never had the chance to continue her education past primary school, she was therefore unable to accomplish her dream of becoming a nurse. Like countless girls growing up in rural Kenya during the 1970s, Margaret’s parents did not see the need to educate a female child. Upon completion of her primary school education, she was left with the options to either get married or begin working to sustain her everyday needs.

Against her parent’s wishes, Margaret chose to spend a term at the high school she had been admitted to. However, before she could take exams at the end of her term, she was sent back to her parents for money in order to pay her tuition fees. Sadly, she was unable to obtain the funds and was forced to leave school and abandon her hopes of becoming a nurse.

Unable to fulfill her ambitions, Margaret found herself moving from job to job until 2002 when she got news of the clothing factory near Maungu that was hiring.

“I had a strong conviction that this was the long-term opportunity I had been looking for when I heard about the Wildlife Works eco-clothing factory,” Margaret, who had learned a few basics of sewing through the years, recalled.

Unfortunately, the machines at Wildlife Works were electronic, as opposed to the manual ones she had been used to. Instead of the sewing job she had hoped for, Margaret was hired as a factory assistant. Among the first to be employed at Wildlife Works eco-factory, Margaret was unfortunately laid off in 2008 when the factory closed for a temporary three-year period. She describes these years as the hardest period of her life.

In developed countries, laid off employees are typically able to find a new job and move on with their lives. However, in a country like Kenya, where the unemployment rate has reached a staggering 40%, this is far from the reality. After the closing of the factory, Margaret learned first hand the hardships faced by those who have no job prospects in their area.

“I had a child to feed and no one was willing to employ somebody who had not gone past primary school- not even as a lowly paid house help,” she laments.

Luckily for Margaret, her husband was employed elsewhere and so they were able to survive on the little that he earned.

Fortunately, Daniel Munyao, the factory manager at Wildlife Works, re-employed Margaret and others when the factory resumed production in 2010. According to Daniel, Margaret is one of the most hardworking employees at the factory. Even when there are no orders being processed, she spends her time learning how to operate the electronic sewing machines.

“I love sewing and I hope that I will one day get a promotion to become a seamstress,” Margaret says.

With what she earns as an employee of Wildlife Works, Margaret hopes to start her own local fashion shop, selling imported second-hand clothes. Her enthusiasm is apparent as she speaks of her future ambitions.

While Margaret might not have completed her secondary school education, she has undoubtedly lived a life full of valuable lessons. One of these, which she would like to pass on, is to never give up on life, to learn to rise past your challenges and make the best out of every opportunity.

At Wildlife Works, we wish Margaret all the best for her employment, dreams and future aspirations.

Today Africa is a destination of second hand clothing. Kenya alone imports over 75 million piecess of second hand clothing and distributes not domestically but in the regional market of eastern and central Africa. This is really shameful that Africa in fact produces just over 5.58 % of the total world production of the cotton fiber but only converts 30% into yarn, fabric and apparel for domestic and regional consumption see table below:

Source ICAC

The cotton produced in Africa is spun and woven in Asia, converted into apparels and shipped to USA and EU to be worn for 2-3 years and shipped back into Africa as used clothing to clothe 70% of Africans .

Historical Background:

Cotton, Textile and Apparel sector has witnessed major changes on global policy front over last decade or so, causing major shift in manufacturing and trade patterns. With Multi Fiber Agreement (MFA) being phased out, several countries in Latin America, Europe and Africa lost their share in global trade mainly to Asian countries of China, India, Bangladesh, Vietnam, etc. The LDC and developing countries in affected geographies were the worst hit, where many units closed down as they were no more viable, creating large-scale unemployment. Among these countries were several major cotton producing nations, which started exporting raw fiber without any value addition. Such countries were mainly from Africa – Burkina, Egypt, Zimbabwe, Mali, Nigeria, etc. and Central Asia – Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, etc.

Importance of the textile and apparel sector:

Cotton, Textile and Apparel sector is one of the important sectors in developing countries across the globe, specifically for those, which have been bestowed with Cotton as one of the natural resources. It not only fulfills one of the basic human needs i.e. clothing, but also provides large-scale employment, specifically at the start of value chain (farming and ginning) and towards the end (apparel manufacturing). The figure below depicts the scope of value addition and employment potential across the CTA sector value chain.

The fact that the annual trade Globally in this segment is in excess of US$ 500 billion also provides opportunity to countries to earn valuable foreign exchange.

Steps taken by various countries for sector development:

At present, the countries where manpower is still inexpensive and cotton fiber is abundantly available like China, India, Pakistan, Brazil, Uzbekistan, etc. are focusing significantly to grow the industry. Ambitious schemes specific to this sector are being launched by federal governments in these countries to boost manufacturing for domestic consumption as well as exports. Similar steps are being taken by countries in Africa as well e.g. Government in Sudan has announced a large package for rehabilitation of many of the textile units, Uganda is implementing a special National Textile Policy to increase investments and make units more competitive in the country, Ethiopia has successfully transformed itself into an investor friendly destination for attracting FDI, etc. On similar lines, Nigeria has also earmarked a fund of N100 billion (~ US$ 650 million) for Cotton, Textile and Garment Industries Revival Scheme. One of the most important impacts of this scheme had been the reopening of the United Nigerian Textile Plc factory in Kaduna, which has recalled thousands of laid off workers.

Background: Cotton Cultivation in Kenya

Cotton was introduced in Kenya in the year 1902 by British Colonial administration. In 1953 the Cotton Lint and Seed Marketing Board was established by the government, whose major role was to undertake production, processing and marketing of the cotton sector. At the same time, the Cooperative Unions were also formed to handle primary activities like input supply and payment to the farmers.

At the time of Kenya’s independence (1963) the industry was dominated by private ginners. Over the next ten years, Government provided a lot of support in the form of a well-organised marketing system and timely payments. In addition to this, the Government also invested in a number of textile mills, which supplied to the large apparel manufacturers.

Till 1991, the Cotton Board of Kenya controlled Kenya’s cotton industry. In 1991, the government decided to liberate the sector and allowed private investors to participate. As a result of this, the government support started declining, which ultimately resulted in the decline in cotton production. In recent years, the production has picked up a bit but has been marred by low market demand and lower returns to farmers.

Cotton Production In Kenya ( In MT) ( 1970-2012) DATA source: National Cotton Council, USA

GDP per Capita Income 1960 – 2010

Today, cotton is mainly grown in Arid and Semi-Arid Areas where there are limited economic activities. It is grown mainly by small-scale farmers in Western, Nyanza, Central, Rift Valley, Eastern and Coast provinces of Kenya. An estimated 200,000 farmers grow most of the cotton on holdings of less than one hectare. Majority of the production takes place in the Eastern zone comprising Coastal, Eastern and North Eastern regions. These regions contribute to ~85% of the production. While the Western zone, comprising Nyanza, Rift Valley and other western regions, contribute to about 15% of the seed cotton production. In Eastern Kenya, the cotton crop is sowed in the month of October whereas in Western regions it is sowed in March.

Necessity for a sector development plan and its key components:

Earmarking a fund for the sector is the foremost step required to be taken by government having sincere plans for revitalization of the sector. Beyond that comes the requirement of a broad vision for the sector, a set of guiding principles to make best use of those funds. While rehabilitating the units may be important where maximum funds need to be committed, but in order to achieve sustainable growth it is important to address the other issues also, to help industry to go that extra mile. This is specifically true for CTA sector where any unit’s viability is a function of several interlinked parameters of raw material, manufacturing and marketing; hence the desired way is to take a holistic view rather than a stopgap arrangement.

The requirement is of developing a comprehensive sector strategy, which addresses the various issues in the sector in most efficient manner. The issues can be high power cost, lack of marketing linkages, low technology level, lack of skilled workforce, absence of incentives to attract FDI, lack of support infrastructure, protection of domestic industry, export incentives, raw material allocation, weak supply chain linkages, etc.

The development of such a strategy will require:

- Mapping of the current status of sector

- Identification of key gaps

- Benchmarking against global leaders

- Developing interventions to address the issues holistically

- Preparing a roadmap for its implementation

How ACTIF can help?

The African Cotton and Textile Industries Federation (ACTIF) is a not for profit regional industry/trade body formed in June 2005 by the Cotton, Textile and Apparel sectors from Eastern and Southern Africa covering the COMESA, SADC and the EAC trading blocks, and currently includes members of National Associations from 25 countries (Botswana, Burundi, Cameroon, Cote d’Ivoire , Egypt, Ethiopia, Kenya, Lesotho, Ghana, Madagascar, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, Sudan, Mauritius, Malawi, Madagascar, Mozambique ,South Africa, Swaziland, Serra Leone , Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe).

ACTIF’s milestone achievements include

- MOUs with COMESA and with the East African Community for trade development along the Cotton, Textile & Apparel (CTA) value chain

- Key contributor to the COMESA CTA strategy and now officially recognized as an implementing partner of the strategy

- Participated in EPA negotiations and developed draft RoO for apparel exports to EU under EPA

- Successful developed a common position white paper for our 20 member countries on AGOA

- Currently engaged in an advocacy project towards the sustainability of AGOA in East Africa and also to our other member countries supported by TMEA.

With the funding support of Center for Development of Enterprise (CDE), ACTIF has recently conducted a CTA sector supply side analysis of four countries in Eastern Africa – Kenya, Sudan, Tanzania and Uganda. This comprehensive study is on the similar lines what needs to be done in Nigeria as well.

With the mandate to pursue development of textile sector in Africa, liaison with international donor partners, network with international consultants and experience of doing similar strategy work, ACTIF is well suited to assist Bank of Industry, Nigeria for development of CTA Sector Strategy for Nigeria.

Given the mandate, ACTIF along with partner international and local consultants would start with conducting a comprehensive mapping of Nigeria textile sector. This step would be followed by a fact-based analysis along with benchmarking with global best practices. The ultimate outcome of this exercise will be:

- An As-is analysis of Nigerian textile industry

- Key risks and mitigation strategy

- Identification of opportunities in the sector

- Interventions for sector growth

- Implementation road map

She is no stranger to the art and handcraft industry; having always been fully involved in doing something good with her hands. She was fortunate to be raised by a very hard working and dedicated women she called Gogo (grandmother). Sibongile Maseko is the Production Manager, a very loyal and soft spoken manager who can be trusted with everything. She is what I would describe as the epitome of a true African woman.

The mother of three beautiful children she lives in Mhlambanyatsi, a small village outside the capital city, with the family she treasures so dearly. She went to Beaconkop Primary School and completed her higher education at Mhlatane near Piggs Peak. While growing up she cared a lot for her mother and her grandmother, something which she is now teaching her own family. She wanted to be a nurse but the competition was too high and her results were not to the standard. It was a sad time for her as she couldn’t re-write her exams due to lack of funds. She was brought up with the money that her gogo earned from selling her handcrafted products and some which her mother earned through cleaning and doing household chores around her area.

She was never discouraged by her upbringing and money shortages and did her level best to go to college where she studied Secretarial. In order to afford the fees she got herself a job as a house helper. After completing college she joined a company called In-Spirit, where she was trained to make earrings using waste magazine papers. When this company closed she continued to make the earrings as a part time job, working for flotsam, the magazine distributors. From these humble beginnings Quazi design was formed. Sibongile was our primary artisan and is now our production manager. Without her we would not be where we are today.

Today she enjoys every single second of her work. She is growing with the company and wouldn’t trade it even for gold.

“This is my place. I am happy here. I had other jobs before but they are not comparable to this one. Through Quazi Design I am able to provide for my family and provide for our customers. They always come first to me and I make sure that we deliver on time. I always look forward to each day at work,” she said.

She enjoys meeting other women artisans outside Quazi in workshops or trainings, coming back she shares all she has learnt.

With her job she has managed to pay for her sons education, who is now at university in South Africa. Not only in her family and at work does she help everyone but also in her community where she is a Peer Educator and Community Developer. She is always there supporting everyone emotionally, physically and otherwise, always willing to roll up her sleeves and help out.

COMPILED BY ZITSILE MAZIYA

Since leaving my job in London as a Fashion Editor to live in Cambodia and then Burkina Faso, my perspective on the fashion industry has been transformed.

It’s been 10 years since I worked for the Sunday Telegraph Magazine. Back then I cared more about style than where clothes came from. Now I’ve seen first-hand how garment factory workers in Phnom Penh live, and I’ve seen how factory-made imports have caused the demise of skills that were once at the core of African livelihood, identity and community.

Globalisation has changed the economies in Africa and Asia beyond recognition. Many are better off than before. Technology has thrown open the door for large-scale industry and mass-made products now flood the world for the benefit of us all. Or for some of us, anyway.

I have come to know some of the women who work in Asian factories and some who work in African villages. Rotha, age 21, is Khmer and lives in Phnom Penh – now a thriving industrial city and tourist hot spot. Ramata, 29, is Fulani and lives in sub Saharan Africa – better known for famine, desertification and conflict.

Young women like Rotha make up the majority of the workforce in the garment factories of Cambodia. Many of them, like Rotha have come from the countryside to work and earn an income for the family back home. She earns the minimum wage ($100 a month) and she sends as much to them as she can but this leaves little to live off. The city is a daunting place and it is normal for girls like Rotha to share their digs with 5 others – a room in a block of several, each with enough space for the women to sleep parallel and a stove to cook on. The bed is an elevated wooden platform with their belongings stored underneath, where cat-sized rats roam at night. They have pink mosquito nets and walls covered with magazine pages showing Khmer women in glamorous dresses. The window overlooks a swamp filled with rubbish.

The Bangladesh factory collapse last year has brought to our attention again the need for better factory conditions for garment workers in developing countries, but we also need to push for a living wage for women like Rotha too. Earlier this year four people were killed during a strike by garment workers demanding higher pay – $160 a month which is still nearly half what the Clean Clothes Campaign calls a living wage.

These workers may think their future lies in the hands of politicians and factory managers. But it is ultimately us, the consumers, who have the greatest power to influence their lives. As the Clean Clothes Campaign’s Tailored Wage report puts it, ‘Survival of the cheapest” has become the leading maxim, both in production countries as well as consumer markets’. If we keep buying cheap clothes and accessories without questioning their source, nothing will change.

In Burkina Faso, Ramata does all her leather weaving work at home, far from the city. There are no machines or factories here: she sits outside on a grass mat under a straw shelter. Her village is in the north, where children, chickens and goats run freely all day. The income she gets from her work enables her to stay in the village, and save a little too. Like her Fulani ancestors, she doesn’t have a bank account but invests her savings in the silver jewellery she wears which she will sell when she needs or wants to reinvest the money elsewhere. The Sahel is an unpredictable place to live and you never know if it will be a good or bad year for crops. Leather weaving is a family tradition that is proving lucrative again for this village. They cannot compete with the quantity of factory made products, but theirs is a unique craft which cannot be replicated easily and their allegiance to this ancient tradition is paying off.

Thanks to the growth of the internet over the last decade, it’s now easier than ever to buy and sell hand-made products from around the world or to at least look up the ethical credentials of the high street shops we’re buying from. We don’t need to travel to Asia or Africa to get the picture. And whenever we make a purchase, we are condoning the behaviour of the retailer, for better or for worse. It is time we started genuinelly caring about the source as much as the style of our clothes. It is time to change our perspective and see fashion in a new way – from the inside out.

BIOGRAPHY

Charlie Davies was formerly Fashion Editor for The Sunday Telegraph Magazine. She founded Precious Girl Magazine, a publication for the garment workers of Cambodia in 2004, and now serves traditional artisans in Burkina Faso with SAHEL Design (www.saheldesign.com). Charlie is the Fashion Revolution Day country co-ordinator for Burkina Faso.