Setting consumers up to succeed: How brands must take responsibility for making clothes last

It’s common to seek instant gratification from a piece of clothing. Yet, the extension of this material interest past the first wear doesn’t happen frequently enough. Purchasing clothes without considering the weight of responsibility in looking after them is a serious oversight, and the rate at which clothing is deemed ‘finished with’ is dangerous to our planet.

The extent to which extending garment life could impact the environment is illustrated by WRAP’s findings that ‘extending the life of clothing by an extra nine months could reduce carbon, waste and water footprints by around 20–30% each1.’

Because the financial investment in fast-fashion pieces is so minimal, the incentive to care for clothes isn’t monetary. Combine this with meaningless, sometimes false claims from brands, and understanding what we are actually buying (and therefore how to care for it) becomes a daunting task.

With brands often shunning responsibility, how can consumers achieve longevity when clothes aren’t made to last? Fast-fashion marketing perpetuates the habits of throw-away culture and fails to educate consumers on garment aftercare, meaning well-made pieces are wasted if consumers cannot care for them.

So, the solution is two fold: brands should facilitate longevity, and consumers should action it. Problem solved, right?

“Pics or it didn’t happen”: a catalyst for outfit redundancy, perpetuated by brands

The relief upon realising an outfit hasn’t yet been documented on social media is a relatable feeling for many. Though a photo may receive compliments, this can be a death knoll to the clothes worn. This nonchalant cycle of admiration leading to rejection comes down to social pressure.

Within Pandora Sykes’ essay collection, ‘How do we know we’re doing it right’, she interrogates these social pressures which subconsciously guide purchasing habits. Upon seeing an influencer wearing something we don’t even like aesthetically, we might still purchase the item for the social ‘seal of approval’. These habits embedded within social media create a catalyst for peer to peer marketing, a sales tool utilised by brands across market levels.

Sykes explores the emotional toll this inadvertent yet constant peer reviewing can take on us, and the endorsement of fast-fashion and single-use clothing it encourages. Offering an aid to this problem, she proposes a question we could put to ourselves pre-purchase which could positively re-enforce an obligation for multiple garment wears and longevity:

“Consider if we have the energy not just to possess something, but to wear it”2.

Extended further, this sentiment could additionally read, ‘and to care for its future longevity’.

Laundering and garment care: How should brands help consumers?

Laundering and garment care: How should brands help consumers?

Modern standards of cleanliness limit garment lifecycles. Many garments are washed before they’re dirty. These wash cycles create abrasion on fabrics, and over time fade colours and slacken elasticity – not to mention micro fibre shedding. Clothing longevity is significantly impacted by this.

In tackling the practice of over-washing, it is crucial to clarify that ‘unwashed’ and ‘unclean’ are two very different things. An understanding of fibre and fabric properties contributes to informed decision making too, but education on the ‘ingredients’ of clothes is rarely prioritised by brands. Brands should encourage growth of knowledge in this area and entice a desire for understanding, not just a desire for material possession.

Realignment of values is needed, refocusing on the unseen acts of garment lifecycles – the mending, hand washing or not washing. If social media is where peer to peer marketing potential lies, brands should market garment aftercare in this space too.

Brands must set consumers up to succeed…

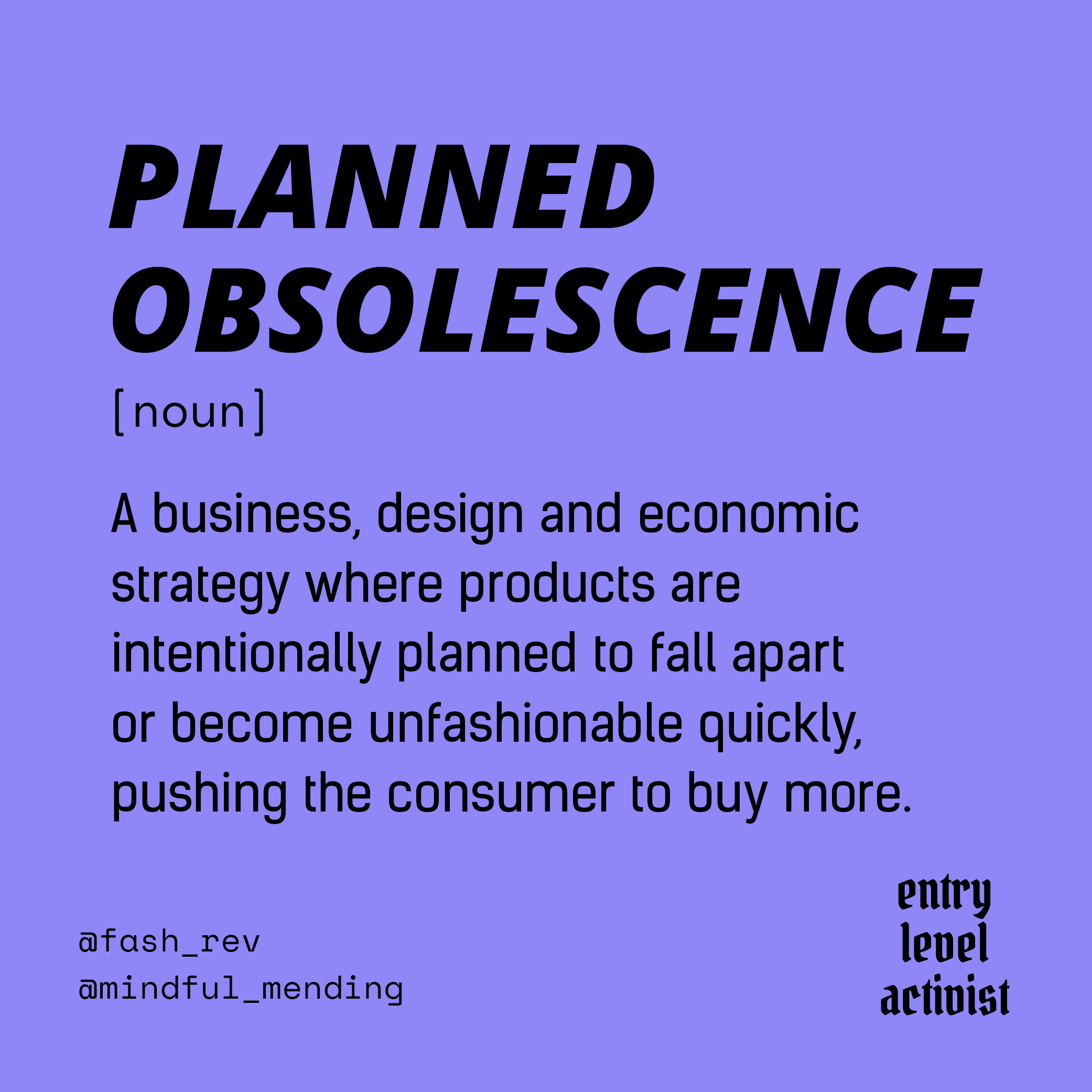

It isn’t fair to burden consumers with this responsibility when often we are set up to fail. Clothes made without consideration of longevity (and sometimes with planned obsolescence) leave us unable to extend garment life, even with the best intentions.

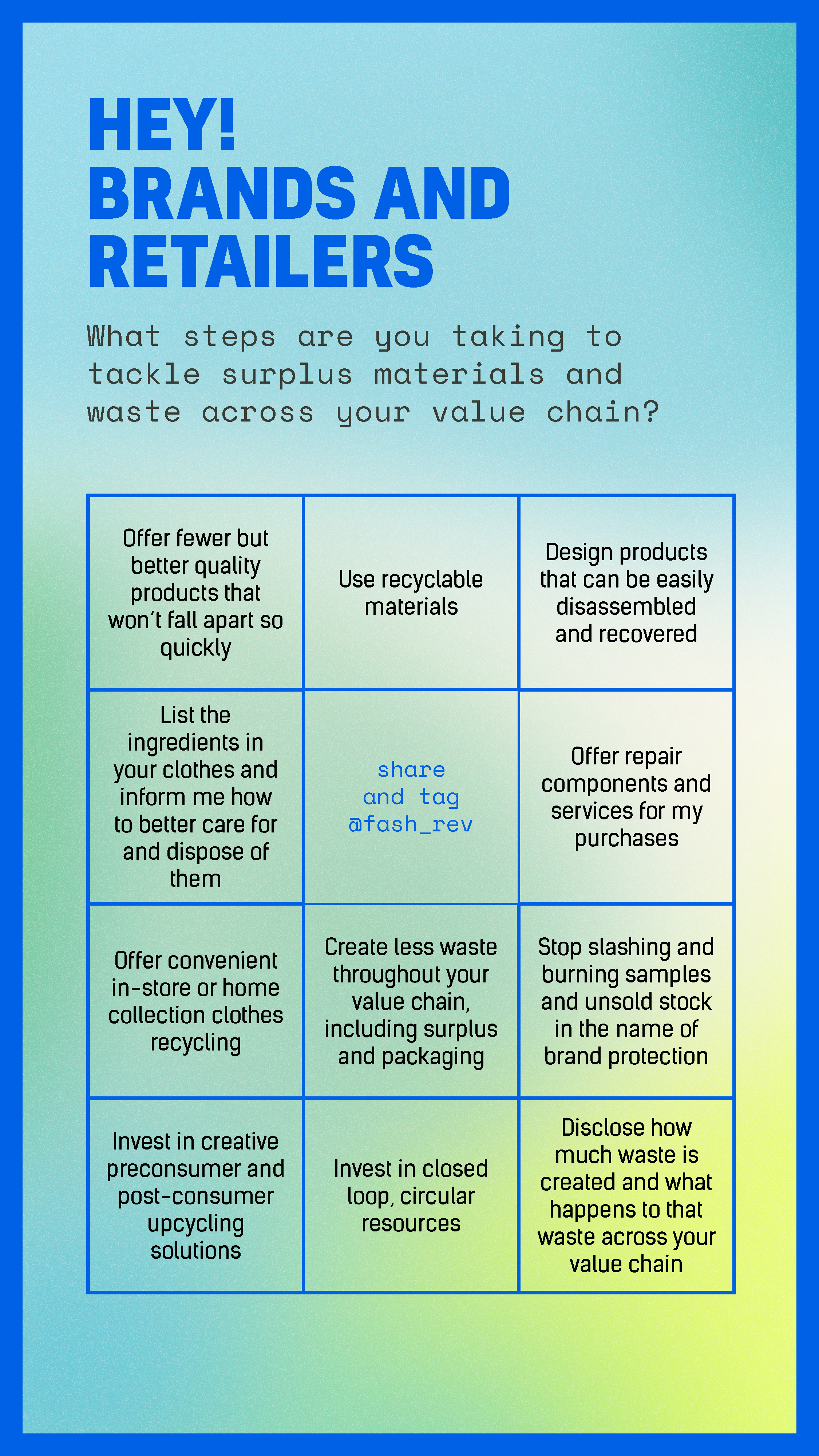

Brands and their professionally trained teams should carry this responsibility by problem solving areas vulnerable to abrasion and improving the longevity of components such as zips. Designing garments for low impact laundering is also essential, and transparent communication of manufacturing processes.

With lead times for fast-fashion getting shorter, regulating and development stages receive less attention. Innovations and design developments facilitating garment longevity are held back within this cycle. Brands need to invest in quality over speed and profit.

Nostalgia and clothing narratives: how can brands contribute?

Emotional connections to clothes that foster caretaking and multiple wears are generally associated with family heirlooms or designer pieces – rarely with fast fashion. Aesthetics can combine with the garment narrative (perhaps a family history, a memory of wearing, or a responsible manufacturing story) and organically form a bond between wearer and garment. Could knowing the story of a garment and positioning ourselves as stewards and caretakers of it be enough to encourage future care and re-wear?

Contradicting the creation of nostalgic connections to clothes is peer to peer marketing. In the context of social media, the memories held in clothes are the very thing preventing re wear and longevity. In order to engage with the history of garments, consumer understanding of universal language and terminologies, as well as brand transparency is vital. This understanding of manufacturing methods and fibre properties is not widespread, and improving this understanding is not a priority for the majority of brands. Brands must re-utilise their social media platforms to show stories of garment longevity and educate consumers.

Pressure must mount on brands to provide this information and educate consumers, so they facilitate longevity and consumers can act on it. As individuals, the least we can do whilst pushing for brands to do the right thing, is to consider that buying the history of a garment means taking responsibly for its future too.

Sources:

- WRAP, 2017, ‘Valuing our clothes’ | https://www.wrap.org.uk

- Sykes, P., 2020, How do we know we’re doing it right?, Penguin