Five things fashion history can teach us about clothing longevity

Niamh Tuft is Fashion Revolution’s global network manager. She is responsible for coordinating with all 92 of our amazing country teams around the world. Below, Niamh shares 5 lessons in longevity ahead of our Black Friday Campaign.

Fashion history can tell us a great deal about where the environmental and social issues in the supply chain have come from. The intrinsic link between the cotton trade and transatlantic slavery, which tells us that fashion was built on and continues to rely on human exploitation, to the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire of 1911, which foretells subsequent industrial disasters like Rana Plaza and last December’s factory fire in Delhi, which killed 43 people. On the environmental front, history tells of rivers running black with pollutants around mills in Victorian England, showing us how producing fashion once relied on toxic chemical pollution just as it does now.

However, fashion history can also shed some light on possible solutions. When it comes to the second-hand trade, mending and clothing longevity, fashion has a few history lessons for us!

-

Visible mending has been trending for over 2000 years

An Egyptian children’s tunic in the Whitworth Gallery’s collection in Manchester is dated to 600-700 BC. It’s extensively darned with coloured wool threads making it one of the oldest pieces of evidence we have that humans have been darning for thousands of years. Many cultures have their own examples. Boro in Japan creates new fabrics from fabric scraps and old clothes, it was widely practiced in peasant communities in the Edo period (1600s-1800s) though born out of necessity due to clothing laws which restricted access to new fabrics it is now widely practiced by visible menders around the world. And invisible mending has been going on for centuries too – Rafoogari in India is used to restore valuable pieces of clothing, it is highly skilled using patchwork and darning to restore antique textiles which have been passed down through generations for hundreds of years.

-

‘It doesn’t fit me anymore’ shouldn’t to be the end for you and your favourite clothes

Many clothes in museum collections show marks of alterations – either for different fashions and styles, for different wearers or for changes in bodies over time. A 2018 exhibition at FIT called Fashion Unravelled exhibited clothes that were altered, mended and repurposed during their lifetimes, the catalogue lists ‘a set of stays (otherwise known as a corset) from circa 1750 was enlarged by adding panels of mismatched fabric at the waist, reshaping it for a changed figure or a new wearer’ and a Paul Poiret dress which passed through generations for nearly 100 years and underwent alterations to the hem and fastenings to suit different wearers.

Clothes were regularly taken apart to be restyled and trims were reused and repurposed. This is why some clothes in museum collections seem to have a mismatch between the age of the textiles and the date of the silhouette.[i] Many of the historic clothes in museum collections survived because they were used in theatre before they were collected by museums and bear the marks of multiple alterations and adaptations.[ii] Multiple studies show that fit is one of the main reasons that people dispose of clothing[iii] but fashion history tells us we can embrace the craft of alteration once again. We don’t have to bid farewell to our favourite pieces, instead we can wear them in a new form.

-

There can be entire professions centred around trading and mending clothes

If we look back in fashion history, we can find many different roles for traders of second-hand clothes and also menders. The names of different roles alone indicate how much specialisation unfolded in this industry, organised from chapmen (peddlers), crokery sellers (itinerant street sellers of second-hand clothes), rag and bone men (ragpickers), slop sellers (second-hand clothes sorters and traders), clothes-brokers (who traded in bulk and sold to smaller sellers), and pawn brokers who bought and sold clothes but also rented them out.

Mending clothes was often done by family members in the home but mending roles were also specialised and households with domestic servants would have a live-in mender.[iv] Alterations could be made by tailors and seamstresses. Cobblers and cloggers who repaired shoes were widespread. Some textile historians even argue that some forms of embroidery originated from mending or patching.[v] So while the loss of mending skills is a key challenge in ensuring clothing longevity, fashion history tells us that skilled specialist roles can be created and sustained to keep clothing in circulation and make loved clothes last.

But it’s not all about the job creation and the economy! Recent research has shown that sewing and mending can have benefits to our emotional and physical health[vi] and across fashion history making and mending has been at the heart of social and political bonds especially among women – from the secret messages carried in patchwork quilts in North America to the political resistance of khadi in Ghandi’s India to early movements for women’s suffrage who often met in sewing circles. Rose Sinclair’s fascinating research on Dorcas societies recently exhibited at Radical New Cross shows us that the value of making and mending is not only economic but social. These sewing societies originated as a philanthropic movement among middle- and upper-class women. They arrived in the Caribbean through missionary women who treated indigenous skills and knowledge with little regard. But the societies become embedded into communities, and Sinclair shows ‘by the 1950s the clubs brought together Caribbean women through textiles to act as networks for social and economic change. As women from the Caribbean moved to the UK in the ‘50s and ‘60s, the clubs moved with them, contributing hugely to diversity in the British textiles aesthetic.’[vii]

-

Some of the most iconic fashion items were second-hand

The second-hand clothing trade has been a vital part of the industry for thousands of years, in fact textiles and clothing including pre-worn items were used as currency to trade and barter. In Venice, there was a whole guild of second-hand clothes traders called L’Arte degli Strazzaruoli who regulated every aspect of the trade when the plague hit the city they were tasked with working with health officials to ensure used clothing did not transmit the disease.[viii]In Florence, some rigatierri (as second-hand traders were named) were amongst the wealthiest men in Florence and appointed to political positions in the city.[ix] In London, the second-hand clothing trade was so large and well organised that in 1843 they formally established an Old Clothing Exchange.[x]

Some of the most recognisable fashion items of the twentieth century came out of the second-hand trade, many from army surplus or labourers clothing adopted by subcultures like the beats, mods and hippies. The pea coat was US military surplus. Blue jeans were surplus from clothing made for factory workers, miners, farmers, and cattlemen. Corduroys were originally worn by workers in French industrial towns. Parkas were army surplus which reached British shores after the Korean war and were widely worn by mods. Donkey jackets were originally worn by coal miners before being adopted by skinheads. So, we have the surplus and second-hand market to thank for many iconic styles of clothing we still wear now.

-

The circular economy doesn’t have to be about making more fashion

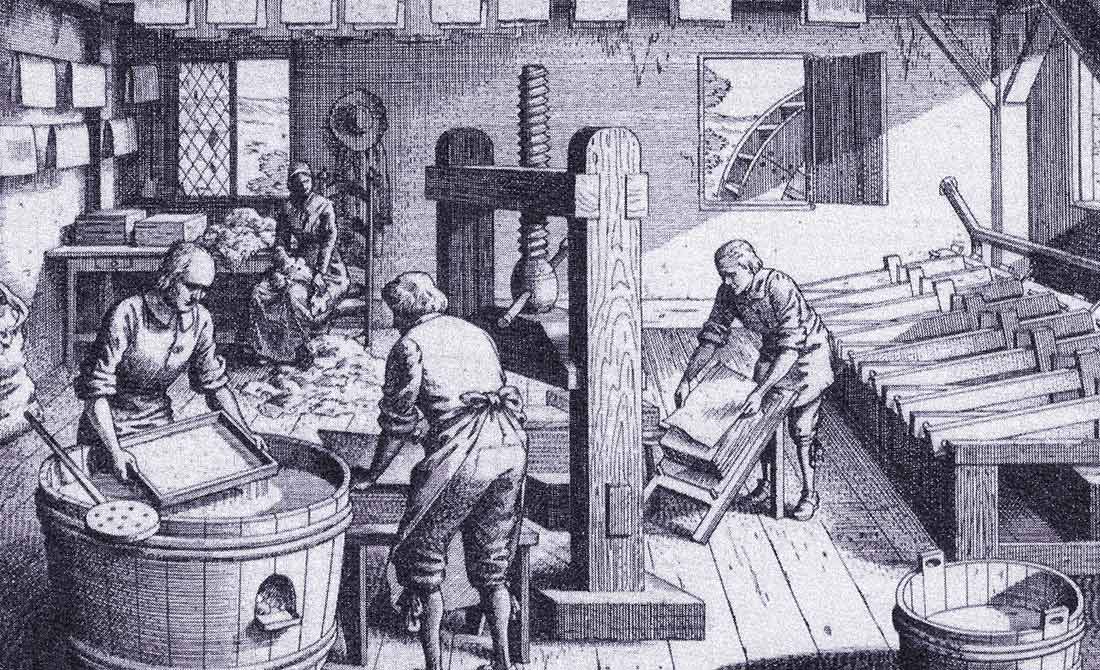

One of my favourite fashion history facts is rooted in recycling. In the 17th and 18th centuries, one of the most ubiquitous destinations for recycled of clothes was to be turned into paper. Established in 1690, the Rittenhouse Mill in Philadelphia recycled rags, including linen linked to the flax industry nearby, into pulp for paper.[xi] The mill still stands today and if you find yourself in Philadelphia you can visit it. On the other side of the Atlantic, Benjamin Law built up an industry which employed over 500 people in West Yorkshire in producing shoddy – wool fibres made from rags, scraps and cast offs. In its heyday, the shoddy capital of England imported waste cloth from all over Europe to create materials not only for clothing but for industrial and domestic use and processed over 30 million pounds per year.[xii]

We should think beyond fashion when it comes to giving the materials that are in circulation the longest possible life. While circularity and textile recycling may be considered as a new technological frontier, fashion history shows us it isn’t something new, archaeological studies across the world (including this one dating back as far as 1500 BC) show that garments and rags were used in applications from health and sanitation, to pottery, salt mining, ship building and insulation.

As we like to remind ourselves at Fashion Revolution ‘sustainability has been trending for billions of years —we are hardwired to it. The culture of excess—mass production, mass consumption and accelerated growth—is, in comparison, a historical nanosecond-long error of judgement’ (Orsola De Castro). We only need to look at fashion history to see that.

References

[i] Farley Gordon, Jennifer and Hill, Colleen (2015), Sustainable Fashion: Past, Present and Future page 6

[ii] Standards in the Museum Care of Costume and Textile Collections page 6

[iii] WRAP (2012) Valuing our Clothes and Laitala, Kirsi ‘Consumers’ clothing disposal behaviour – a synthesis of research results’ International IJC 38 (2014)

[iv] König, Anna. ‘ A Stitch in Time: Changing Cultural Constructions of Craft and Mending’ Journal of Current Cultural Research 5 (2013)

[v]. Gillow, John; Sentance, Bryan (1999). World Textiles. Bulfinch Press/Little, Brown. ISBN 0-8212-2621-5

[vi] BBC Arts and UCL https://www.bbc.co.uk/mediacentre/latestnews/2019/get-creative-research and Journal of Public Health https://academic.oup.com/jpubhealth/article/34/1/54/1550848

[vii] https://www.gold.ac.uk/news/rose-sinclair—dorcas-societies/

[viii] Allerston, Patricia. “Reconstructing the Second-Hand Clothes Trade in Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century Venice.” Costume 33 (1999).

[ix]https://www.academia.edu/7516473/The_Trade_of_Second_Hand_Clothing_in_Fifteenth_Century_Florence_Organisation_Conflicts_and_Trends

[x] http://www.nzdl.org/gsdlmod?e=d-00000-00—off-0hdl–00-0—-0-10-0—0—0direct-10—4——-0-1l–11-en-50—20-about—00-0-1-00-0–4—-0-0-11-10-0utfZz-8-00&a=d&c=hdl&cl=CL1.18&d=HASHf2f1117351b350b3e62854.7.9

[xi] The Rittenhouse Mill and the Beginnings of Papermaking in America. James Green (1991)

[xii]https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=29QFBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA201&dq=shoddy+industry+benjamin+law&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwi-kN6my_jsAhUITcAKHVweDjoQ6AEwAXoECAgQAg