Fashion on the Ration

Today we are thinking about how to be more careful with our use of the earth’s precious resources. A key part of that is clothing and the fashion industry. We are wasteful, let us not beat about the bush. And the question I have, as a historian, is: can we learn anything from history?

In 1941 the British Government introduced clothes rationing and the following year Utility clothing was swiftly followed by austerity measures that limited the length of women’s skirts, the number of buttons on a jacket, the shape of lapels and the width of the gusset in women’s knickers. Men did not get off scot free either. Their socks, which had until then been knee length, were cut to just nine inches, which caused a roar of disapproval and questions in the House of Commons. That outcry was matched when turn-ups on their trousers were banned. In short, Britain had to cut its cloth to fit the new reality of clothing shortages.

There was the belief during the war that anything that could be done to help the war effort, to reduce waste and to make-do with what limited materials people had was valid. Gill Tanner, now 87, remembers exchanging clothes with her neighbours ‘it was lovely. We got “new” clothes, well new to us, and that was exciting.’ Make-do and Mend brought out some of the best in expert seamstresses. Eileen Gurney unpicked an old edge-to-edge coat, put a deep hem on it, made a turn down collar ‘and la voila! A warm and luscious new coat!’

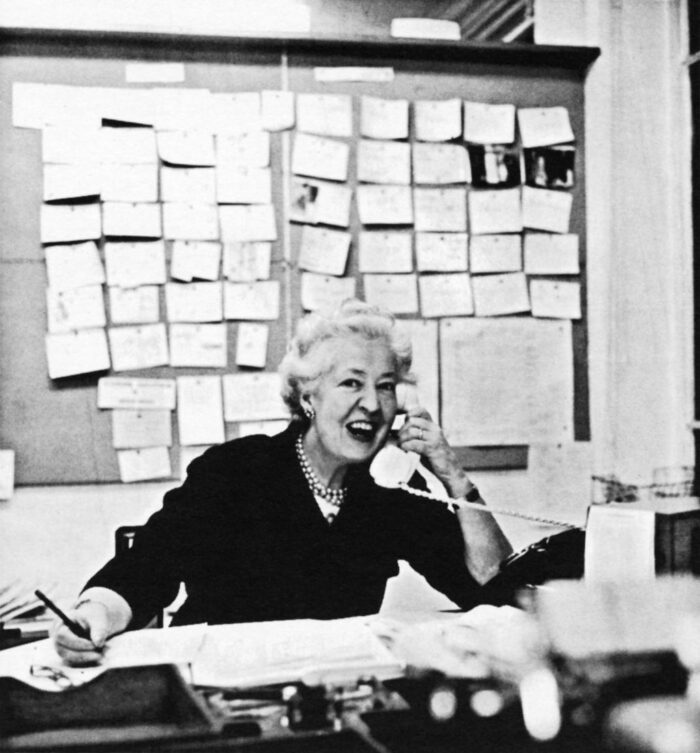

Clothes rationing, Utility, Austerity designs and then, in September 1943, Make-Do and Mend, presented a serious trial for women but also to the fashion industry. It challenged the editors of newspapers and magazines to work out how best to advise their readers. With Paris out of the fashion picture from the summer of 1940 and the severe curtailing of clothes through the rationing scheme it might be supposed that it was a dire time for clothes. In the literal sense it was: Vogue tried to cheer up its readers by reminding them that for a quarter of a century the advice had been ‘to put your money into one good outfit and vary it with accessories.’

However it was not all doom and gloom. Audrey Withers, the wartime editor of British Vogue told readers of the American edition that she had three suits, one woollen dress for going out in the evening and two pairs of slacks and jumpers for the weekend. She was proud of her reversible topcoat from Bradleys and her impeccable navy wool dress from Angele Delanghe but her main message was one of versatility. Her clothes had to last. Quality not quantity was her message.

While the government was encouraging people to be as frugal as possible, Audrey Withers was reassuring them that they did not have to go around looking scruffy. Far from it, the emphasis should be on ingenuity and creativity. ‘Hats and accessories can let in light-heartedness’ she told her readers, ‘with ingenuity and style you can snip as you please for you cannot ration style.’

When soap was rationed Vogue told its readers that white gloves and shirts were out, as were pastel shades, blonde hair and silk stockings. Fortunately, we do not have such limitations on our clothes today but I would suggest that looking back at some of the ingenious ways people got around clothing shortages could help us to reassess our own usage. I shocked a journalist recently by telling her that I cleaned my black leather boots. She immediately stuck her feet under her chair and said ‘don’t look at my boots, for goodness sake.’ As I spend so much time writing about the war years, I have always been cautious about buying new clothes. Don’t get me wrong – I do love having a new outfit – but I am very happy to share with my well-dressed neighbour. I follow Audrey Withers’ good advice that accessorising an existing outfit can be just as rewarding as buying something new. And so much kinder to the planet.

***

Julie Summers is the author of Dressed for War, the Story of Vogue Editor, Audrey Withers, from the Blitz to the Swinging Sixties. Dressed for War tells the story of a now-forgotten historical figure who was described, during the Second World War, as the most powerful woman in London. She was behind the designs for the Austerity clothing restrictions and worked closely with great designers such as Hardy Amies, Digby Morton, Victor Stiebel, Edward Molyneux and Elspeth Champcommunal. Julie Summers is a historian, author of 13 books including Fashion on the Ration (Profile Books 2015), and the Royal Literary Fund Fellow at St Hilda’s College, Oxford.