Ethiopia: The story behind the ‘Rising Star’ in textile production

In Addis Ababa, Amharic language filled its bustling crowded streets. The city’s smoggy air and high altitude of 2600m contributed to our difficult adjustment to limited oxygen. It was mid-May 2022, when we, a team of researchers from Drip by Drip, started our five week exploration of Ethiopia, “the rising star” in textile production.

Drip by Drip is a German-based nonprofit organisation that exists to tackle water pollution through the textile industry. Currently, we are working in Bangladesh on two different projects. For the future, we want to extend our impact into more countries that suffer from decreasing clean water resources, which led us to Ethiopia.

We set out to understand the current situation of Ethiopia’s textile and garment industry. In doing so, it was our goal to learn about the current political and economic situation and to understand whether Ethiopia will be the next Bangladesh. Additionally, through a three-week collaboration with Sequa gGmbH, an NGO funded by GIZ (German society for international cooperation) and UKAID, we had the opportunity to visit local factories, the Hawassa Industrial Park, and speak with a large international buying agency, which acts as a liaison between major brands and production facilities. We also conducted interviews with stakeholders, which included local and foreign factory managers, factory employees, NGOs, B2B customers, ministry staff, and entrepreneurs. To protect the identity of the interviewees we will not disclose their names.

The Rising Star

Our preliminary research depicted Ethiopia as a budding force in textiles, with the potential of competing against China’s and Bangladesh’s industry. However, we quickly discovered the lack of validity and substantiality in our online sources. The lack of data brought up questions about Ethiopia’s labor costs, work environment, industrial waste, access to water, infrastructure, investments, foreign connection, the security and health system.

In 2020, the Economic Intelligence Unit, predicted an economic growth in Ethiopia of 7% .(1) In comparison to other African countries, whose common growth rate ranged from 2%to 3%, Ethiopia appeared to be advancing faster. Additionally, the International Monetary Fund predicts an increase in their gross domestic product (GDP) from 3.84% in 2022 to 5.72% in 2023, 6.23% in 2024, and so on.(2) On top of this, Ethiopia has a population of roughly 110 million people, with an expected growth rate of 2.49%.(3) A country with an exponentially growing population offering a plethora of job opportunities with no legal framework of a legal minimum wage is an attractive option for investors. Because: A growing population ensures investors a growing workforce. Additionally, Ethiopia offers low labor costs. Where there is a low labor cost, you will commonly find textile and garment businesses. The average pay wage for garment workers range from $340 to $95 per month, while in Ethiopia, the pay wage is set at $26 per month.(4) This causes a slow and silent factory shift from China, Vietnam and Bangladesh to countries like Ethiopia. Last but not least, the war that began in the Tigray region in the north of the country about a year ago and has spread to more southern regions.(5), is having a destabilising effect on the entire country.

Ethiopia’s Export and Import Dilemma

To investigate further, we scheduled meetings for the first two weeks of our exploration with stakeholders in the field of environmental science, textile production, and business management. Stakeholders included locals, professors, consultants, activists, businesspeople, and fashion designers. Our preliminary research depicted Ethiopia on the cusps of a new era as they transitioned from a developing state to an industrial state, but it became evident that we drastically underestimated the situation. With every conversation, the illusion of the “rising star in the textile industry” vanished. Under former Prime Minister Zenawi Haile, the Ethiopian government pursued a Growth and Transformation Plan, which expired in 2020. This plan pursued various targets, one of which was the development of industry. Under these targets, 13 industrial parks were established for different manufacturing industries – the textile and garment industry were one of them.

Industrial parks (IPs) are portions of a city zoned for industrial use. Through the construction and promotion of IPs, Ethiopia approached investors and companies to establish themselves at industrial parks; unfortunately, with no long-term success. We learned from an Indian-owned garment company that their production capacity has shrunk by 50%. Adding to the dilemma, the US terminated the AGOA agreement, which forced the closure of many factories. The African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) is a US agreement that allows AGOA member countries to export duty – free and tax – free to the United States. Ethiopia has long been a member, but in November 2022, Biden terminated that alliance on the grounds that Ethiopia harbors “violations of international human rights.” Such termination caused major producers and fashion companies, such as the PVH Group, to halt production in Ethiopia. With AGOA, companies exported 60% – 80% of their goods. Since its termination, exports have shrunk to 20% – 30%, along with a decrease in the country’s number of textile companies. We visited the industrial park in Hawassa, the largest IP hosting 52 halls that are now mostly empty due to the AGOA termination. Hawassa’s IP stood as a foreshadow or a glimpse into the future for many foreign investors, especially from India, China, Bangladesh and the US.

During AGOA, a majority of Ethiopia’s goods were exported to the US. Now that AGOA has ended, factory owners want to focus on the EU market. The EU is a more complicated venture though, as it has more regulations and requirements than the US, such as certifications like CmiA, OEKO-TEX Standard 100 and SteP or the BSCI. For Ethiopian textile companies, this would mean a new type of commitment.

Exporting and Importing with an Ethiopian-Owned Factory

We often came across non-certified Chinese, Indian or Sri Lankan operated factories that usually import their cotton from China or India. Fortunately, we were able to visit an Ethiopian – owned textile production site located in Kombolcha, about an hour flight from Addis. Kombolcha Textile Share Company is a 100% Ethiopian operated factory that uses 100% Ethiopian cotton and has a water treatment plant. The factory is also OEKO TEX SteP and ISO 14001:2015 and ISO 9001:2015 certified – a real rarity in the Ethiopian market. The factory owner of Kombolcha Textile informed us about his problems with importing chemicals, dyes, or spare parts for machines. Since Kombolcha Textile is a certified company, he is obliged to use certified chemicals, but Ethiopia does not produce those. In the past, he purchased his dyes from a Swiss company that had stores in Ethiopia. Unfortunately, the Swiss company closed its stores, which means the factory owner must now import all those goods. To pay for and import goods from abroad, an Ethiopian company needs foreign exchange (forex). Foreign exchange is one of the biggest challenges of the industry. Unlike Euro (EUR) or US Dollar (USD), Ethiopian Birr (ETB) is not an official trading currency.

We learned about Ethiopia’s foreign exchange issue from a GIZ employee. To understand the following example, let’s define two terms:

● Export turnover is the sale proceeds or a company’s earnings from their exported goods.

● Foreign exchange (forex) is trading one currency for another.

So, if an Ethiopian company’s export turnover, or earning amount, is 100 EUR. 80% of their earnings will be converted to ETB and 20% will be converted to forex. This leaves them with 80 ETB and 20 EUR. Then, 80% of that 20 EUR must be given to the Ethiopian government for forex taxes. This means that the company has only 4 EUR remaining. Remember, ETB is not an official trading currency and they are not allowed to convert the 80 ETB to EUR or USD. Therefore, the company can only use the remaining 4 EUR to import goods. Needless to say that 4 EUR is not enough to import goods from abroad. Therefore, the instability of import and export costs makes it nearly impossible for smaller companies to survive, especially when they rely on a small amount of forex.

On top of this, the cost of homegrown cotton increased significantly in Ethiopia. In comparison, the Indian cotton price is 2.10 USD, which is about 109 ETB per kg, and the Ethiopian cotton price is 130 to 150 ETB and rising. As a result, many small local factories, like Kombolcha Textile, now use their own stock of cotton for production, which will only last for another 6 months. Overall, we discovered that the priorities of the industry are on one hand export growth and on the other hand employment growth. When it comes to water management, a very complex issue, there is a lack of focus on water supply and sanitation for both large industries and local manufacturers, which led us to the next challenge.

The Water Problem

We had the pleasure of speaking with professors from a highly renowned university in Ethiopia. They shared with us Ethiopia’s rich water history that gave the country its nickname – the “Water Tower” of Africa. A local friend informed us about Ethiopia’s government-supervised water meters for private households. These meters are read monthly and consumption must be paid accordingly. Unfortunately, this is not the case for industries. Through a conversation with a consultant from an Environmental Consultancy Service, that proposes for environmental reform to the Ministry of Industry as well as the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, we learned the following about industrial water consumption:

IPs are built by the government, and foreign investors rent out the space and use it for production. Foreign investors pay for rent and electricity, but water is free. They are allowed to drill their own water boreholes and are not required to prove consumption. Additionally, treatment of wastewater is recommended, but not required for production. Therefore the consultancy company advocates for more regulations surrounding wastewater decontamination and water extraction.

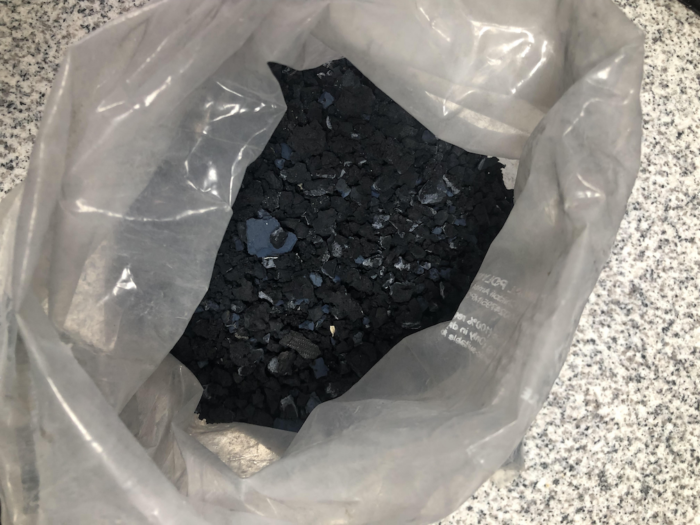

An employee from an Indian – owned textile company spoke with us about their wastewater system and treatment plant. They installed their wastewater treatment plant a year after the company opened. It is designed to treat chemicals and dyes so that the wastewater can be recycled back into the company’s water cycle. However, the plant did not have the capacity to treat the amount of wastewater produced. So, up until 2 years ago, production simply discharged their excess wastewater, especially in the rainy season, to the surrounding fields. Farmers from the surrounding areas rightfully complained about the issue, and the government gave the company a warning. Since then, wastewater has not been discharged, but no solutions about the contaminated fields, which still release an acrid smell, have been discussed. Then, another issue came up. It was further explained that when the water goes back into production to be reused, 10% is left as compressed sludge residue in the form of granules. The company produces 5 bags of granules per day. These bags were simply disposed of in surrounding areas. The government then required the company to store the bags, which are now kept in a warehouse onsite, but there is no solution for its final disposal.

Conclusion

Without the warmth and hospitality of the Ethiopian people, we would not have been able to learn anything about textile production. The biggest challenge for us was the access to data, because especially in the area of water there are almost no reliable surveys. So the personal conversations with the different stakeholders were essential for our assessment. Ethiopia clearly has the potential to become the next “rising star” in the textile industry. However, the political and economic challenges are still too great at the moment. Therefore, we leave the country with mixed feelings. Ecologically, it remains to be feared that the uncontrolled water extraction by the industries, as well as the growing interest in local cotton cultivation, will lead to a significant shortage of clean groundwater. For the economic situation of the unemployed population, on the other hand, the IPs could be a long-awaited blessing. Similar to Bangladesh, positive effects on the emancipation of women can also be expected. A dichotomy that can be resolved: An early enactment of laws regulating the use of water as a resource throughout the production cycle. Because without clean water, even the greatest economic boom cannot prevent another humanitarian crisis. We will continue to follow the developments with great interest.

A report by Charlotte Kühl & Michelle Dixon for Drip by Drip

Charlotte Kühl is a student for clothing technology and fabric processing. During her involvement with Drip by Drip as a working student, she went on a seven-week research trip to Ethiopia, to analyse the status quo of the textile and apparel industry. This article is a summary of her findings.

Michelle Dixon is a writer and visual artist with an interest in fashion and water pollution. She holds a Master of Arts in Nature – Culture – Sustainability Studies and her research encompasses fashion and agriculture, fashion and water security, and fashion and grace. She is a researcher and project assistant at Drip by Drip.

The copyright for the pictures belongs to Charlotte Kühl.

Further reading

Fashion’s opportunity to be a force for good

Fashion’s role in fighting human trafficking, reducing vulnerability, and uplifting humanity

Beyond Compliance in the Garment Industry