Dead White Man’s Clothes

Liz Ricketts is co-founder of The OR Foundation, an organisation working to expand perspectives across borders and beyond single stories. Here, Liz shares her research on the importation of secondhand clothes in Ghana, a practice she’s been observing since 2011.

It’s December 10th, 2016 and Abena has just grabbed a ‘first selection’ top from her stall and thrust it into my hands saying, “Happy Birthday! I give you this White Man Has Died jeans top.” She laughs – a deep belly laugh – because I am White and she thinks it is funny that I call secondhand clothing “obroni w’awu.” This is the third jeans tops she has gifted me in a month and it dawns on me that in addition to being generous Abena thinks my clothes are shabby. I do often show up to the market unkempt – wrinkled, sweaty and probably a little skimpy for her taste – Accra is hot. But I hope that she hasn’t found my appearance disrespectful. The party continues. We are celebrating three events simultaneously: my birthday, Mabena’s birthday (another retailer like Abena) and Ghana’s 2016 Presidential election.

When I think about Kantamanto, I think about moments like this.

But Kantamanto represents many things. Spanning roughly seven acres in the center of Accra, with 5,000 individual shops and a labor force of 30,000, Kantamanto Market is the largest secondhand clothing market in West Africa, if not the largest in the world. On the ‘elder’s’ side of the market, near the vests, there is an archway with the words “Obroni W’awu,” an Akan phrase that means “Dead White Man’s Clothes.” When secondhand clothing started flooding into Ghana in the 1960s people assumed that the cheap imports had been the property of deceased foreigners, hence the name. The truth – that the clothing was simply excess that living consumers in the USA and Europe no longer wanted – was less than obvious. Ghanaian consumers also preferred the idea of purchasing clothing that had been ‘retired’ over clothing that had been ‘discarded’ – who wouldn’t.

Kantamanto’s elders report that when the secondhand clothing trade began it was considered good business. When Ghana gained independence in 1957, wearing “western” clothing was a symbol of prestige, so there was a market eager to purchase obroni w’awu. Secondhand clothing was considered high quality in terms of finishing details, fit and durability. Kantamanto’s retailers report that back then working in Kantamanto was a dignified job, often a family business, that allowed for upward mobility. Similarly, importers say that back then the business was exciting. Some importers even traveled to the USA and Europe to advise exporters on what would sell well in their country.

While there is still a market for secondhand clothing in Ghana, business is no longer good and excess has become a familiar concept. Today, there is too much clothing of low quality. Today, importers and retailers alike have asked me to tell you to stop sending them your rubbish.

I first visited Kantamanto in 2011 and I remember being shocked by the limp piles of clothing strewn across the walkways, people walking on top of them as if they had no value. Over the years my partner Branson and I traveled to Kantamanto to source material for various upcycling projects and we noticed that the amount of clothing underfoot was increasing. After tripping over a pile of jeans and TOMS shoes we decided it was time to dig deeper.

Branson and I launched Dead White Man’s Clothes as a multimedia research project in 2016. We began with three lines of inquiry. First, it was clear that not all of the clothing sent to Kantamanto was fulfilling its purpose of being re-worn, but exactly how much of the clothing became waste and how did this waste impact both people and the environment? Second, what roles were necessary for the trade and under what conditions did Kantamanto’s workforce labor? Third, how did consumers view the secondhand clothing trade?

A few of the headlines are as follows:

Excess with nowhere to go. Roughly 15 million items are unloaded in Kantamanto every week. Kantamanto may be the largest market in Ghana, but there are many more secondhand clothing markets throughout the country. With a national population of just over 30 million people, not all of this clothing can possibly find a home. Through surveys, interviews, waste analysis and synthesizing various data points over a two year period we have concluded that 40% of the clothing in each bale becomes waste. This waste is dumped in overflowing sanitary landfills (thus undermining the engineered safeguards such as leachate control), dumped in the Gulf of Guinea or sent to open, unplanned landfills where it burns in the backyards of Accra’s most vulnerable neighborhoods (sometimes referred to as slums). In 2017, secondhand clothing from Kantamanto Market alone made up 20% of the planned capacity of Kpone Landfill, the primary engineered landfill for the city of Accra. I would like to underscore that because many people in Ghana do not have consistent household trash pickup, almost all of the clothing lying in Ghana’s landfills comes directly from secondhand markets.

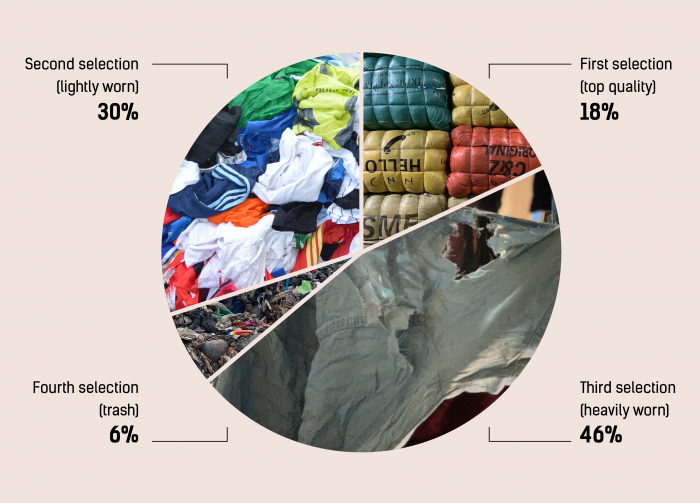

Retailers shoulder the risk. This waste makes it harder for retailers to turn a profit. Once purchased, bales are sorted into four piles called “selections”. The first selection (top quality) makes up an average of 18% of the bale, whereas third selection (heavily worn) makes up 46%. Fourth selection is trash which consists of (intentionally) slashed garments, partial garments and items with stains all over them – garments that never should have been exported to Ghana. Retailers do not discover the quality of the bale until after purchasing it and few importers will accept returns. Combine this with the fact that prices are driven down by oversaturation and only 16% of retailers make a profit. We have interviewed hundreds of retailers and not one wants their children to take over the business.

Kayeyei risk everything. The kayayei, or kaya, are female head porters. As young as 14 these girls migrate from the Northern Region of Ghana and find work transporting bales of clothing from importer to retailer and everywhere in between. The bales are 120-200 pounds, often the entire body weight of the kayayoo who earns a meager $0.30-$1 per trip. Girls are frequently injured when bales fall on their limbs and kayayei have died because the load was too heavy. Some of Kantamanto’s retailers refer to the kayayei as the ‘slaves of the system’.

Secondhand is traditional. Almost everyone in Accra regardless of class, gender, age and profession shops secondhand. Generally, clothing exported from the Global North is still perceived as high quality. But not everyone enjoys navigating Kantamanto, shuffling through the piles and piles of clothing to find what they are looking for. Today, many middle and upper class consumers shop from Instagram and Facebook sellers who have done the hunting for them and present a curated selection of ‘vintage’ items. The idea that Kantamanto, as a place, is not ‘modern’ is becoming increasingly salient and tensions are high – Kantamanto sits on valuable real estate in a city that is experiencing rapid ‘development’.

This paints a fairly dismal picture, but that is because the secondhand clothing economy is a mirror of the ‘firsthand’ clothing economy, not because Kantamanto is a failure. Kantamanto is a (necessary) outlet for the excess created by the fashion industry, it is part of a global waste management system. But the deficit myth has long deluded the Global North into believing that poor, naked people in the Global South need our material and cultural assistance. With this idea we also seem to have convinced ourselves that secondhand clothing markets are retail utopias where every item is sold and loved forever. But of course, this cannot be true. There is simply too much clothing. There is an excess of excess and the more we oversaturate secondhand clothing markets like Kantamanto, the more we devalue clothing in terms of real and nominal value. All brands – high and low, first selection and third selection – end up on the floor of Kantamant soaking up mud and printed with footsteps. Very little is precious because the supply never stops.

But Kantamanto has not failed. Take a step back and you see that this place, and this community, has much to teach us. First of all Kantamanto’s retailers re-commodify, or extend the life of, between 20-30 million items a month. And they do so by not only selling clothing but also washing, mending, over-dyeing, ironing, tailoring and upcycling items. Kantamanto is equal parts mall, studio and factory. I feel confident in saying that no retailer, or mall, in the USA puts in the same level of effort to keep clothing out of landfill. And yet secondhand markets in the Global South are never praised for their “sustainable” behavior or their contribution to the circular economy. Which brings me to another headline:

Clothing is a resource. In Kantamanto consumers don’t take “wrong size” for an answer. If they find something they like there is a tailor around the corner who can make it fit. And outside of Kantamanto, the small scale tailoring industry is still thriving. Ghanaians purchase cloth and take it to their family tailor, co-designing looks for special events. With this practice comes a level of agency that most consumers in the USA or Europe lack. Yes, Ghanaians follow trends, but they don’t expect to replicate their favorite celebrity’s look with a click of a button. Instead, Kantamanto’s consumers view clothing as material, or a resource – a means to an end.

So, what can be done?

First and foremost we have to regulate production volumes and remove excess from the business model of fashion. With virtually no limits on production, and no regulation on import volumes in Ghana, Kantamanto serves as an open valve, not a bottleneck, to continued growth and profit in the Global North. The benefits remain lopsided. While the Global North works to achieve diversion targets, our waste compounds existing environmental, infrastructural and health issues in Ghana. For those of us who live in the Global North, waste is still out of sight out of mind, the risk is not felt. But in Ghana, waste is a public health crisis because textiles wrapped around plastic choke the gutters and increase the risk of malaria and cholera. Diverting clothing from landfills in the Global North by dumping this excess on the Global South is absurd. Calling this a solution, or referring to this as recycling, is even more absurd.

Perhaps it is all of those birthdays but I am no longer as idealistic as I used to be. While it would be nice to think that we could halt the flow of waste, I believe that the amount of clothing exported to Ghana will only increase over the next decade. As we transition to a global, circular textiles economy, where waste is reimagined as a “resource”, or an “asset”, I believe we have two choices:

Commodify human byproducts (including clothing) in a way that repeats patterns of exploitation, extraction and inequity where the Global North reaps the economic benefits while the environmental consequences are largely felt by the Global South.

Or

Address the problem of waste in a way that inspires reckoning, recovery, peace and equity.

We choose the latter. For us, this means continued commitment to our Kantamanto community and investment in Kantamanto’s future as a model of circularity. Please follow along at @theorispresent and deadwhitemansclothes.org or reach out to lizandbranson@theor.org to get involved.

[youtube v=”8vV5379KuDA”]