IT’S TIME FOR FASHION BRANDS TO PUT THEIR MONEY WHERE THEIR EMISSIONS ARE

Fashion Revolution, the world’s largest fashion activism movement, is at Climate Week NYC 2024 with a clear message: fashion is fueling the climate crisis, and major fashion brands must urgently put their money where their emissions are.

We’re calling on major fashion brands to invest at least 2% of their revenue in a fair transition away from fossil fuels – like coal – to renewable energy sources – like wind and solar – to power fashion’s supply chain in a clean way.

Fashion is one of the most polluting industries on the planet, with fossil fuels burned at every stage of production. The industry alone is set to overshoot the 1.5°C limit by 50%, doubling emissions rather than halving them as the science is crying out for. Frequent climate catastrophes, like extreme heat, flooding, and droughts are devastating the livelihoods of workers across global garment supply chains, with extreme weather estimated to cost nearly one million jobs by 2030.

Fashion Revolution’s new report, What Fuels Fashion? reviewed 250 of the world’s largest fashion brands and retailers and ranked them according to their level of disclosure on climate and energy-related data in their operations and supply chains. The findings revealed that major fashion brands aren’t doing enough to cut fossil fuel use in their supply chains. 86% of major fashion brands lack A PUBLIC coal phase-out target, and only 3% disclose the level of financial support provided to supply chain workers affected by the climate crisis.

By investing at least 2% of their revenue into clean, renewable energy and upskilling and supporting workers, fashion could simultaneously curb the impacts of the climate crisis and reduce poverty and inequality within their supply chains. Climate breakdown is avoidable because we have the solution – and big fashion can certainly afford it.

WE ARE CALLING ON

- Policymakers to enhance regulation

- Investors to fund and co-fund renewable energy and decarbonisation projects

- Citizens to use their voice- email major brands and retailers and call on them to invest at least 2% of their annual revenues into their decarbonisation and Just Transition efforts

- Civil society, academia, journalists to leverage data and findings to scrutinise and verify the public claims made by brands

Big fashion can no longer mask its lack of decarbonisation progress with vague, insufficient targets and pilot projects that fail to benefit most of the supply chain. The need for system change is undeniable. It’s time for brands to put their money where their emissions are.

You can read the report here. Email your brands here.Traditionally, fashion brand compliance efforts consisted of offloading the direct responsibility for human and environmental rights onto their suppliers, who absorbed this burden as a cost of securing the brand’s business. While the argument that brands aren’t responsible for the welfare of the workers in their supply chain has become indefensible, today many major fashion brands engage in purchasing practices with suppliers which are volatile and abusive. These practices, also referred to as unfair trading practices, include: cancelling and delaying orders; refusing to pay for orders; demanding retrospective discounts; issuing sudden changes in order volumes; and paying for orders very late. Sometimes, customers are wearing clothes before big brands have even paid the factories that made them.

To delve deeper into this topic, we invited a range of industry experts and stakeholders to provide on-the-ground insights and perspectives on how both brands and governments can remedy these issues. Here, you can explore some viewpoints featured in the Fashion Transparency Index 2023.

DEBT AND THE GARMENT INDUSTRY: DEBT AS A VEHICLE FOR GARMENT WORKER EXPLOITATION IN THE GLOBAL SOUTH

FAROOQ TARIQ, Pakistan Kissan Rabita Committee

TESS WOOLFENDEN, Debt Justice, UK

Throughout the Global South, many countries and workers depend on the garment industry for their income. Yet, conditions are often deeply exploitative and dangerous for workers, while profits are typically enjoyed by big multinational companies. Many of these inequalities link directly to debt.

For centuries debt has been weaponised against Global South countries and communities to the benefit of Global North elites.Not only do Global North governments, institutions and corporations use debt to extract vast wealth through interest payments ($2.5 trillion since 1970) shrinking the resources that countries have to meet citizens’ needs, they also use debt to tell countries what to do, forcing them to implement harsh austerity-based reforms as conditions of their loans. Global North governments and dominated institutions (like the World Bank and IMF) argue that these reforms – including cutting public spending, deregulating labour markets and liberalising economies – will achieve economic growth and allow countries to repay their debt and fund their development. But after decades, these outcomes have not materialised. Instead, Global South economies have stagnated and poverty and inequality rates soared while foreign investors have enjoyed new access to Global South markets on favourable terms.

For garment workers throughout the Global South, these reforms have created the perfect conditions for wage theft, poor and unsafe working conditions and restricted opportunities to unionise while multinational corporations make mass profits. Making up a majority of the workforce, women have been especially impacted whilst also bearing the brunt of public spending cuts which have forced vital services like healthcare into the home. These impacts are well documented, yet only 14% of major fashion brands involve gender experts in their human rights due diligence processes.

While there has been debt cancellation in the past, debt burdens and thus the ability of Global North powers to enforce economic reforms, remain high as the root causes – irresponsible lending and the Global South’s colonially rooted dependence on borrowing – remain unaddressed.

There are currently 54 countries in debt crisis. Many of these countries also rely on their garment industries, like Pakistan and Sri Lanka. In Pakistan for example, soaring inflation as a result of the debt crisis is causing the cost of essentials like food to skyrocket, which alongside poor and unpredictable wages in the textile sector means many workers can’t afford to eat full meals or pay for necessities. The high debt burden in Pakistan also means that governments do not have the resources to meet citizens’ needs, like funding healthcare or addressing the climate crisis.

In 2022, Pakistan was hit by devastating floods caused by the climate crisis. Recovery and reconstruction is estimated to cost at least $40bn but the country is expected to pay over $18bn in debt repayments this year.1 The floods have hit the textile industry hard. Yet because of a lack of national resources due to the debt, the industry has not been able to fully recover, putting many jobs and livelihoods at risk.

But all across the world, impacted communities are resisting the impacts of unjust debt and forced austerity. In Pakistan, the Kissan Rabita Committee and APMDD Pakistan are demanding an end to the unjust debt plaguing the country, calling on the government to stop repaying its loans, for Global North lenders to cancel the debt, and for living wages for all workers. Global South countries urgently need debt cancellation, free from economic conditions, so they have the resources and policy space to uphold the rights and wellbeing of all workers and citizens.

Addressing a lack of transparency is also key. How can we adequately hold corporations, governments and institutions accountable if we don’t know the true scale of what is happening? In the fashion industry this means big brands publicly disclosing information on their operations. For debt, it means creditors and borrowing governments sharing accessible information on their loans so citizens can hold their governments and lenders accountable.

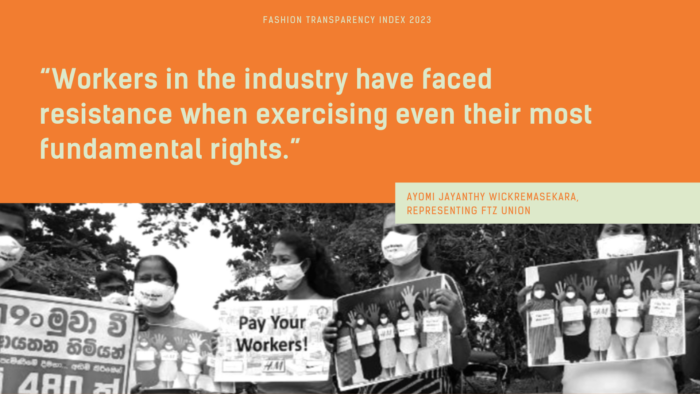

LOOKING AT UNIONISATION IN THE SRI LANKAN GARMENT SECTOR

AYOMI JAYANTHY WICKREMASEKARA, FTZ Union

Free Trade Zones & General Services Employees Union (FTZ&GSEU) was founded in 1982, which aims to protect the labour rights of workers within the Free Trade Zones and throughout Sri Lanka, especially women within the garment industry.

FTZ&GSEU leverages its vast network of garment workers, among both formal and informal union members, as well as their expertise in Sri Lankan labour rights and incorporates their lessons learnt when operating with garment factories’ management and owners.

The apparel industry in Sri Lanka plays a key role in developing the economy. For decades the industry has provided rural communities, particularly women, with access to economic opportunities. Subsequently, over 85% of employees within the industry are women, the majority of whom come from lower economic backgrounds and whose labour is undervalued. Despite the economic strength of this industry, many female workers are subject to widespread violations of the labour law and are highly vulnerable to gender-based violence (GBV) from their employers, supervisors, boarding house owners and other men living and working around the garment factories. This includes, but is not limited to, sexual, physical, and verbal harassment, exchange of sexual bribes for promotions and restrictions on utilising washroom facilities during work hours. Located far from their hometowns and separated from their families, workers are often reluctant to voice their concerns in fear of retribution from their employers.

Increasingly, violations of labour laws have also been observed with factories appearing to target and dismiss unionised workers. Even before the pandemic, trade union membership was low with a unionisation rate of only 15% across all sectors, and just 5% in the apparel sector. Sadly, even at a critical time, workers in the industry have faced resistance when exercising even their most fundamental rights.

FTZ&GSEU, alongside other trade unions, suggested to the EU GSP Monitoring mission the below findings:

The ILO has found the Sri Lanka Board of Investment (BOI) at high risk of violating international legal standards on freedom of association. The workers’ situation is the most arduous in the EPZs where freedom of association remains an illusion and employer-labour relations are usually managed by employee councils. These often undermine freedom of association and collective bargaining. Workers in Sri Lanka do not have access to remedy in case of anti-union retaliation as only the Department of Labour can bring cases concerning anti-union discrimination before the courts.

- Adapt the BOI Labour Standards and Employment Relations Manual to bring into an agreement with the international legal standards on freedom of association.

- The 40% union membership threshold should not be compulsory for recognition as a bargaining agent. This provision has no justifiable basis as stated by the ILO Committee of Experts on the Application of Conventions and Recommendations (CEACR).

- Change the Labour Law to bring into an agreement with ILO Convention 98, in particular regarding the limitation that only the Department of Labour can bring cases concerning anti-union discrimination to the courts.

- The CEARC also found entry into EPZs for trade union representatives are restricted. This is not justifiable and the right to access should be granted.

- Adapt policies on EPZs in particular discontinue the promotion of Employee Councils, and allow trade unions to take their place.

In Sri Lanka there are approximately 400 Garment factories. While some are being close down, there is only one Collective Bargaining Agreement at present (NEXT Manufacturing and FTZ & GSEU) and One Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) signed by FTZ and two other Unions (NUSS and SLNSS) with Joint Apparel Association Forum (JAAF).

“Brands need to go beyond policy commitments when it comes to freedom of association and lay out exactly how they plan to actively engage with trade unions and worker representatives along their supply chain to ensure genuine worker engagement. Importantly, this should include how they will work with suppliers to ensure a conducive environment for freedom of association and the development of representative trade unions at factory level. This is all the more important with the roll-back of trade union rights in multiple garment supplying countries and the continued rise of alternative ‘worker voice’ mechanisms; from the more traditional worker committee structures that often undermine trade union rights to collective bargaining, to the increasing use by brands of ‘worker voice’ tools that can simply never do the job of genuine dialogue and negotiation. As the sector continues to be impacted by economic turbulence, it is more important than ever that workers are able to collectively bargain for safer workplaces and decent livelihoods to ensure that it is not the lowest paid in the supply chain paying the cost for ongoing instability. And as more apparel brands become subject to due diligence legislation, now is the time for buyers to undertake stakeholder mapping along their supply chains to ensure that they are supporting workers, and importantly rights-holder groups such as women and migrant workers, to join and form trade unions to engage in participatory due diligence processes.”

Natalie Swan

Labour Rights Programme Manager, Business and Human Rights Resource Centre

FASHION HAS A PURCHASING PRACTICE PROBLEM: INDUSTRY WATCHDOG NEEDED

HILARY MARSH, Transform Trade

Fashion has a purchasing practice problem. Whilst the data from this year’s report demonstrates an upward shift by brands in their transparency of human rights due diligence processes (68% in 2023 compared to 34% in 2020), there has been no movement on publicly committing to paying suppliers within even 60-day time frames. Late payments are a part of a bundle of purchasing practices which directly impact on a supplier’s operations, potentially creating the very issues due diligence tries to mitigate. Voluntary initiatives to improve purchasing practices have proven ineffective; regulation is desperately needed to embed stability and consistency in fashion supply chains and level the playing field.

It is concerning that the simple act of disclosing policies to pay suppliers within a maximum of 60 days is proving a struggle for major fashion brands, with only 11% publishing a policy to pay suppliers within 60 days, stagnant since last year. Much of the disclosure made by brands and retailers, for instance in HRDD reporting, is based on information provided by suppliers, about the workers employed by suppliers or environmental impacts incurred within supply chains. The lack of information provided about the actions of the retailers themselves is a vital missing piece of information. Particularly given the role that brands’ purchasing practices can play in enabling or undermining improved labour rights. For example, the ILO’s 2017 report pointed to a correlation between companies committing to pay at least the cost of production and a 20% uplift in wages. When brands pay their suppliers months late, then it is suppliers, and ultimately garment workers (experiencing poor labour rights including incorrect overtime payments, delayed and inaccurate wages), who are effectively subsidising fashion brands’ operations, and as it stands only 4% of fashion brands share the number of orders that have retrospective changes to their previously agreed payment terms.

But it isn’t just late payments which impacts suppliers’ operations. In a survey from the University of Aberdeen released this year of 1000 Bangladeshi manufacturers producing clothing for global brands and retailers, more than 50% reported at least one of the following four unfair practices by brands and retailers: cancellation of orders, price reduction, refusal to pay for goods dispatched or in production, and delaying payment of invoices of more than three months. These methods used when fashion brands buy clothing dump inappropriate, unexpected, and excessive risks and costs onto their supplier factories and undermine the market for brands treating manufacturers fairly. Practices like this were once widespread in the food retail sector but were banned with the establishment of a Supermarket Watchdog enforcing a Code of Practice. Its introduction has seen a huge reduction in these practices with 79% of suppliers surveyed reporting experiences of code breaches in 2014, falling to 29% by 2021.

We urgently need legislation for the fashion sector. Luckily, there is growing support to follow suit. The proposed ‘Fashion Watchdog’ (or Fashion Supply Chain Code Adjudicator, as set out in a UK Private Member’s bill) would oversee fashion brands’ buying practices and be able to reverse unfair decisions in line with a code of practice for the industry.

If you are in the UK and in support of fair purchasing practices by fashion retailers and brands selling in the UK market, head to our Fashion Watchdog MP Pledge page, and contact your MP today to ask them to support this vital proposal.

STATE-IMPOSED FORCED LABOUR IN TURKMENISTAN’S COTTON HARVEST: THE NEED FOR SUPPLY CHAIN TRANSPARENCY

RUSLAN MYATIEV, Turkmen.News

ROCIO DOMINGO RAMOS, Anti-Slavery International

Turkmenistan’s cotton industry is underpinned by a state-sponsored forced labour system.

Every year, the government forces hundreds of thousands of public sector workers, like teachers and doctors, to pick cotton, pay a bribe, hire a replacement worker, or face threats of lost wages and termination of employment. In many cases, children pick cotton alongside their parents. Farmers are forced to meet official production quotas under threat of penalties. Private businesses are also forced to contribute workers or services, for example, vehicles to transport forced labourers. The Turkmen government is resisting reforms to the industry and has taken harsh actions against those who report on abuses in the sector.

Given the government’s total control of cotton production, for any company sourcing cotton or cotton products directly from Turkmenistan, it is a fact that their product is tainted with forced labour. But there is also risk for those who source from countries that produce textiles using Turkmen cotton, yarn and fabric. For companies in the United States, due to a Customs and Border Protection Withhold Release Order on Turkmen cotton, they are illegally importing such products. To assess and mitigate that risk, full mapping of supply chains and transparency is integral.

Turkmenistan is the 10th-largest cotton producer in the world and has a vertically integrated cotton industry. Turkmen cotton from any stage of production can find its way into supply chains. According to UN Comtrade data, in 2022 Turkmenistan exported cotton and cotton products valued at almost US$300 million to several countries across the world. Research by Cotton Campaign members on commercial trade and value chain databases shows that Turkmen cotton enters the global markets through two main streams:

- As finished goods produced in Turkmenistan and exported through direct trade routes or transhipped to, for example, Kazakhstan, Russia, Belarus, Italy, the U.S., and Canada;

- Through suppliers in countries that produce textiles using Turkmen cotton, yarn and fabric, in particular Turkey, but also China, Pakistan, and Portugal, among others. For example, Turkmenistan is the largest source of fabric imports to Turkey, and the second largest source of yarn, after Uzbekistan.

The repressive system of state imposed forced labour in Turkmenistan makes it impossible for brands and retailers to conduct any credible due diligence on the ground to prevent or remedy forced labour. For this reason, companies must map out their entire textile supply chains, down to the raw material level, and eliminate all cotton, yarn and fabric originating in Turkmenistan, with a focus on identifying the intermediary routes by which it reaches supply chains. It is disappointing that transparency is low across fashion’s supply chains, especially at raw material level where just 12% of major fashion brands publish their raw material suppliers, like cotton farms.

Transparency helps a company’s own knowledge and due diligence and supports civil society working to bring all companies to the same level. Yet, as we see with this year’s Fashion Transparency Index, this level of transparency is minimal.

WE CAN’T LET ANOTHER GENERATION OF GARMENT MAKERS DEPEND ON POVERTY WAGES.

ANNE BIENIAS, Clean Clothes Campaign

The Fashion Transparency Index and the Transparency Pledge have been at the forefront of pushing for the enormous increase in the amount of brands publishing their suppliers list over the past few years, with more or less detail, which has been immensely important for the work of the Clean Clothes Campaign network and other labour rights groups.

It’s impossible to hold brands accountable for violations in their supply chain if there is no oversight of which brands are producing where. However, transparency at this level is not enough. A list of factories on a brands’ website or on the Open Supply Hub does not tell a consumer under what conditions their item of clothing was made or how much the maker was paid to make it.

This is tricky, as more and more brands make bold claims or promising commitments about paying living wages to workers in their supply chain, roughly 28% of the brands covered in this research. We can clearly see that this is the first step towards a living wage and with the lowest threshold. The more specific it gets (so moving from a commitment to an action plan and then to implementing that action plan) the fewer brands are able to provide any evidence or details.

Only three brands in this research can provide evidence of paying some of their workers a living wage, despite decades of corporate social responsibility and voluntary multi-stakeholder initiatives. This unfortunately means that most workers in these brands’ supply chains are still paid poverty wages; a minimum wage – where there is a statutory minimum wage – or per piece. Statutory minimum wages are far below living wages in garment production countries.

The minimum wage in Bangladesh has not been revised for five years, which essentially means that workers’ purchasing power has decreased over the past five years because of inflation and rising cost of living. The situation in other countries is similar: workers’ wages don’t rise as quickly as inflation. The gap between wages earned and what constitutes a living wage is growing, despite all good intentions by some fashion brands. It’s clear that workers can’t wait for brands to figure it out by themselves, but that immediate action in the form of legislation or other binding mechanisms to stop this crisis is required.

That is why Clean Clothes Campaign is a key partner in the Good Clothes Fair Pay campaign, calling on the European Union to adopt specific legislation that requires companies to conduct living wage due diligence in their supply chains. We can’t let another generation of garment makers depend on poverty wages.

You can read more about decent work and purchasing practices in the 2023 edition of the Fashion Transparency Index.

Header photo by Marcel Strauß on Unsplash

Fashion Revolution Week is our annual campaign bringing together the world’s largest fashion activism movement for seven days of action. It centres around the anniversary of the Rana Plaza factory collapse, which killed around 1,138 people and injured many more on 24 April 2013.

This year, as we marked the tenth anniversary of the Rana Plaza factory collapse, we remembered the victims, survivors and families affected by this preventable tragedy and continue to demand that no one dies for our fashion. To define the next decade of change, we translated our 10-point Manifesto into action for a safe, just and transparent global fashion industry. Our campaign platformed the work of our diverse Global Network who provided local interpretations of their chosen Manifesto point(s). We believe that while fashion has a colossal negative impact, it also has the power and the potential to be a force for change. Together, we expanded the horizons of what fashion could – and should – be.

Here, catch up on some of the week’s highlights and find out how to stay involved with our work, all year round.

Remembering Rana Plaza

Fashion Revolution Week happens every year in the week coinciding with April 24th, the anniversary of the Rana Plaza disaster. On April 24th 2013, the Rana Plaza factory building in Bangladesh collapsed in a preventable tragedy. More than 1,100 people died and another 2,500 were injured, making it the fourth largest industrial disaster in history. On April 24th, we paused all other campaigning to pay our respects to the victims, survivors and families affected by this tragedy, and came together as a global community to remember Rana Plaza.

As we reflect a decade on, we are inspired by and celebrate the progress made in the Bangladesh Ready-made Garment (RMG) sector by the Accord. The International Accord on Fire and Building Safety was the first legally-binding brand agreement on worker health and safety in the fashion industry and is the most important agreement to keep garment workers safe to date. This year, we pay tribute to the joint efforts of all Accord stakeholders who have significantly contributed to safer workplaces for over 2 million garment factory workers in Bangladesh, including the Bangladeshi trade unions representing garment workers, alongside Global Union Federations and labour rights groups. We welcome the introduction of the Pakistan Accord and would like to see the adoption and success of the International Accord replicated in all garment producing countries.

Manifesto for a Fashion Revolution

Our theme for Fashion Revolution Week 2023 was Manifesto for a Fashion Revolution. Back in 2018, we created a 10-point Manifesto that solidifies our vision to a global fashion industry that conserves and restores the environment and values people over growth and profit. This year we called on citizens, brands and makers alike to sign their name in support of turning these demands into a reality, boosting our signature count to 15,500 Fashion Revolutionaries and counting. We are immensely grateful to everyone who has and continues to sign; our power is in our number and each signature strengthens our collective call to revolutionise the fashion industry.

To campaign for systemic change in the fashion industry, we themed the week around complementary Manifesto points, providing ways to be curious, find out and do something daily around each of them. From supply chain transparency to living wages, textile waste to cultural appropriation, freedom of association to biodiversity, we shared global perspectives and solutions to fashion’s most pressing social and environmental problems.

Over the past ten years, the noise around sustainable fashion has only got louder. But meanwhile, real progress is too slow in the context of the climate crisis and rising social injustice. That’s why Fashion Revolution Week 2023 was an action-packed and future-focused campaign that amplified the actions and perspectives of Fashion Revolutionaries around the world.

View this post on Instagram

Global Conversations

To capture these global perspectives, we launched the Fashion Revolution Map on Earth Day, which coincided with the start of Fashion Revolution Week. Developed by Talk Climate Change, the Map served as a global forum to reflect on the week’s themes and events, using our Manifesto as a talking point. Fashion Revolutionaries continued the discussion offline by inviting their family, friends, colleagues and classmates to imagine what a clean, safe, fair, transparent and accountable fashion industry would look like with us. These conversations were then recorded on the Map as a source of inspiration and knowledge exchange.

Anyone can be a Fashion Revolutionary; it starts with a simple dialogue about the changes you want to see in the fashion industry. Make your voice heard by contributing to our map today and help change the fashion industry through the power of conversation!

View this post on Instagram

Good Clothes, Fair Pay Highlights

Ten years on from Rana Plaza, poverty wages remain endemic to the global garment industry. Most of the people who make our clothes still earn poverty wages while fashion brands continue to turn huge profits. At Fashion Revolution, we believe there is no sustainable fashion without fair pay which is why we launched Good Clothes, Fair Pay as part of a wider coalition last July. The Good Clothes Fair Pay campaign demands living wage legislation at EU level for garment workers worldwide, building on Manifesto points 1 and 2.

During Fashion Revolution Week, our EU teams coordinated awareness events, campaigns and marches to mobilise signatures for this campaign. On April 25th, we headed to the European Parliament with Fashion Revolution Belgium to demand better legislation in the fashion industry. The day of action consisted of a panel discussion between Members of the European Parliament and impacted fashion stakeholders, and ended with a stunt outside the Parliament. Fashionably Late highlighted that the EU is running out of time to act on poverty wages in fashion. This stunt was replicated by our teams in Germany, France and the Netherlands throughout Fashion Revolution Week to demonstrate EU-wide solidarity with the people who make our clothes.

We have less than three months left to collect 1 million signatures from EU citizens to push for legislation that requires companies to conduct living wage due diligence in their supply chains, irrespective of where their clothes are made. If you are an EU citizen, sign your name here. If you’re unable to sign, please support the campaign by sharing it far and wide online.

View this post on Instagram

Fashion Revolution Open Studios Highlights

Fashion Revolution Open Studios is Fashion Revolution’s showcasing and mentoring initiative since 2017. Through exhibitions, presentations, talks, and workshops with emerging designers, established trailblazers and major players, we celebrate the people, products and processes behind our clothes.

This Fashion Revolution Week, Fashion Revolution Open Studios joined forces with Small but Perfect to spotlight the work of 28 European SMEs taking part in their circularity accelerator project. Forming part of this European events programme, Fashion Revolution Open Studios held a two-day event in partnership with The Sustainable Angle and xyz.exchange at The Lab E20. The event showcased seven innovative designers from the Small But Perfect cohort of sustainable SMEs and displayed how they are embedding circular solutions into their work, from crafting grape leather handbags to developing community approaches to making and working together. Alongside the exhibition, there were livestreamed webinars, workshops and panel discussions to explore the projects and hear about some of the the challenges facing small businesses and the industry at large in switching to circular business models.

Global Network Highlights

With 75+ teams from all around the world, Fashion Revolution Week 2023 championed the perspectives and contributions of our Global Network. Here are just a small selection of highlights from our country teams:

Fashion Revolution New Zealand unpacked each Manifesto point with industry trailblazers in an Instagram Live series.

Fashion Revolution teams in Bangladesh and Sweden co-organised a virtual panel discussion on shifting consumer behaviour.

Fashion Revolution Singapore celebrated the launch of their digital zine MANIFESTO.

Fashion Revolution teams in Iran and Germany collaborated on Women, Life, Freedom, a joint exhibition.

Fashion Revolution Nigeria shared the stories and journeys of local slow fashion brands.

Fashion Revolution Argentina invited us to join their Wikipedia edit-a-thon.

Fashion Revolution teams in Vietnam, South Africa and Scotland hosted local community clothing swaps.

Fashion Revolution India won the Elle Sustainability Award for Eco-Innovation in Fashion.

Fashion Revolution Uganda brought together the country’s top designers and brands at Kwetu Kwanza.

Fashion Revolution teams in UAE and Canada both held local design competitions for students.

Fashion Revolution Hungary championed the revival of traditional folklore practices in clothing and fashion.

Fashion Revolution USA discussed the fashion industry’s impact on people and planet in a 2-part Zoom series.

Fashion Revolution Uruguay hosted Fashion Celebrates Life, a community picnic themed around Manifesto point 10.

Fashion Revolution teams in Chile and Portugal shared their Fashion Revolution Week highlights with us on Instagram Live.

You are Fashion Revolution

We are so grateful to everyone in our community for getting involved in Fashion Revolution Week on social media and beyond. Every single voice makes a difference in our fight for a fashion industry that conserves and restores the environment and values people over growth and profit.

While Fashion Revolution Week 2023 may be over, our community, our campaigning and our movement continues, 365 days a year. Please join us in fighting for systemic change by:

Following us on social media: Stay up-to-date by following us on Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, LinkedIn and YouTube, and signing up to our weekly newsletter.

Finding your country team: Connect with the teams in your region by following them online, attending their events and volunteering with them. Find your country team here.

Using our online resources: Our website is a treasure trove of information, from how to guides and online courses to annual reporting on transparency on the fashion industry. Get started here.

From all of us in the Fashion Revolution team, we appreciate your support and we look forward to seeing you next year!

24th April 2023 marks 10 years since Rana Plaza. During Fashion Revolution Week, we are #RememberingRanaPlaza and demanding that no one dies for fashion. As we reflect, we are both inspired by the progress made in the Bangladesh Ready-made Garment (RMG) sector and reminded of the scope of human and environmental issues yet to be addressed in the global fashion industry.

What happened at Rana Plaza?

On 24 April 2013, the Rana Plaza factory building in Bangladesh collapsed in a preventable tragedy. More than 1,100 people died and another 2,500 were injured, making it the fourth largest industrial disaster in history. Rana Plaza was not the first or last garment factory disaster and was a symptom of the common problems faced by producer countries worldwide. Rana Plaza further exposed the widespread lack of transparency across global fashion supply chains, and how a lack of visibility can ultimately cost lives. Without transparency, issues remain hidden and unresolved at their root.

It is not by coincidence, but by design, that within the global fashion industry, garment worker wages are artificially low and that brands continue to source from regions where it is impossible, difficult and/or unsafe for workers to form trade unions and bargain for greater rights. The global fashion industry has continually relied on voluntary commitments which have allowed brands to continue with business as usual. A lack of living wages, freedom of association, collective bargaining, health and safety and traceability continue due to poor progress on transparency in these areas. A critical first step toward accountability, therefore, is greater transparency.

View this post on Instagram

What is the International Accord?

The Bangladesh Accord on Health and Safety (now known as the International Accord on Fire and Building Safety) was signed just weeks after Rana Plaza and is a landmark agreement that brought together brands, retailers, trade unions and supplier factories to address building and fire safety in garment factories in Bangladesh. It was the first time that global fashion brands acknowledged their direct responsibility for factory conditions in their supply chains – and 192 fashion brands are currently signed up.

The International Accord is the first legally-binding brand agreement on worker health and safety in the fashion industry. It was formed with the understanding that voluntary measures alone are not enough to address issues of health and safety because they lack transparency, enforceability and assurance of meaningful representation of workers and trade unions. The Accord is unique in being supported by all key labour rights stakeholders in Bangladesh and internationally, and being legally binding. It is the most important agreement to date to keep garment workers safe.

The Accord has three main goals:

- Promoting a culture of workplace safety by training Safety Committees and encouraging workers to identify, address and monitor safety hazards at factories.

- Preventing fire, electrical, structural, and boiler safety accidents through inspections and remediation programs led by specialist, independent engineers.

- Providing a trusted avenue for workers to raise safety concerns through an independent complaints mechanism.

This year, we pay tribute to the joint efforts of all Accord stakeholders who have significantly contributed to safer workplaces for over 2 million garment factory workers in Bangladesh, especially the global trade unions representing garment workers who were at the forefront of this ground-breaking agreement. You can find a list of organisations to support at the end of this blog.

You can read more about the International Accord via Clean Clothes Campaign and watch the below video which celebrates the measurable achievements of the Accord:

What is the Pakistan Accord?

In Pakistan, unions have taken the example of the Bangladesh Accord and are working to adapt it to their own national circumstances. Starting in 2018, labour organisations in Pakistan have been campaigning for a Pakistan Accord on Fire and Building Safety.

The Pakistan Accord is a legally binding agreement between global unions, IndustriALL and UNI Global Union, and garment brands and retailers for an initial term of three years starting in 2023. The factory listing of these brands would cover approximately 300-400 facilities in Pakistan. The program in Pakistan will include key features from the 2021 International Accord.

35 global brands and retailers have now signed the Pakistan Accord. Fashion Revolution stands in solidarity with all organisations who are calling on major brands and retailers to sign the Pakistan Accord and demands the industry protects progress so that a disaster like Rana Plaza never happens again.

Rana Plaza could have happened anywhere, as it was a devastating outcome within an industry rife with human rights abuses and environmental degradation. This disaster exposed that a lack of transparency costs lives. Whilst 48% of major brands and retailers included in the Fashion Transparency Index are disclosing their first tier supplier lists, supply chains remain complex, fragmented, deregulated and opaque with half of brands scoring 0-2% overall in the Traceability section of the report.

How transparent is the fashion industry?

Since Rana Plaza, there has been greater scrutiny on the global fashion industry and pressure for brands and retailers to be more transparent. The Global Fashion Transparency Index is one tool that Fashion Revolution has developed to help bring about systemic change in the industry.

The Index was created in 2017, recognising that a lack of transparency costs lives and allows human rights and environmental issues to thrive, unaddressed.Transparency alone wouldn’t have prevented Rana Plaza but without it, it is impossible for companies to make sure human rights are respected, working conditions are safe and the environment is protected without knowing where their products are being made. The aim is for this information to be used by individuals, activists, experts, worker representatives, environmental groups, policymakers, investors and even brands themselves to examine what big fashion brands are doing, hold them to account and work to make change a reality.

Our findings highlight an increased level of transparency over the last 5 years. In 2017, just 32% of 100 brands reviewed disclosed their first tier manufacturing lists. In 2022, 48% of 250 brands included in the Index now disclose their first tier manufacturing lists. Furthermore, in 2017, 0% of brands reviewed disclosed their tier 3 supplier lists. In 2022, 12% out of 250 brands included in the Index now do. While this progress is encouraging, it begs the question, what is still being hidden?

Ten years after Rana Plaza, there is still much to be done in the global fashion industry. Find out how you can take action and support organisations working on the ground in Bangladesh below…

How can I take action?

If you are a citizen:

- Call on major fashion brands and retailers to sign the Pakistan Accord. You can show your support by signing this petition and can directly lobby brands to sign by demanding action on social media or via email. Here is a list of brands who have and haven’t signed.

- Sign the Good Clothes, Fair Pay campaign if you are an EU citizen and, whether you can sign or not, help spread the word by sharing our posts on Instagram (@goodclothesfairpay) and Twitter (@goodclotheseu).

- Ask #WhoMademyClothes? and #WhoMadeMyFabric?

- Sign and share the Manifesto for a Fashion Revolution ahead of Fashion Revolution Week 2023.

If you are a policymaker:

- Support better regulations, laws and government policies that require transparency and corporate accountability on environmental and human rights issues in the global fashion industry.

- Be more proactive at responding to ‘red flags’ and risk factors associated with labour exploitation and environmental damage in the global fashion industry.

- Read and listen to the viewpoints of workers, communities and experts in the Global Fashion Transparency Index to inform your policymaking activities. Note that the views presented here are not exhaustive and we recommend seeking out and speaking with other affected stakeholders.

If you are a major brand and retailer:

- Sign onto the International Accord.

- Sign onto the Pakistan Accord.

- Publish your supply chain right down to the raw material level as soon as possible, doing so in alignment with the open data standard, and uploading the list to the Open Supply Hub.

List of global organisations to support

The following organisations have been central to the development and adoption of the International Accord:

Trade Union Signatories of the Accord

Witness Signatories of the Accord

- Worker Rights Consortium

- Clean Clothes Campaign

- Maquila Solidarity Network

- International Labor Rights Forum

International Accord Steering Committee Chair

Other organisations supporting garment workers in Bangladesh

- Bangladesh Worker Solidarity Centre

- National Garment Workers Federation

- Labour Behind the Label

- Awaj Foundation

- Remake

Header image: J Williams on Unsplash

A divat szempontjából a 2022-es év keserűen zárult: az ultra fast fashion divatmárka, a SHEIN lett a világ legnépszerűbb piactere, miközben a termékeiben – a Greenpeace jelentése szerint – olyan veszélyes vegyszerek találhatóak, amelyek sértik az EU-s jogszabályokat. Emellett számos greenwashing kampányt azonosíthattunk a különböző divatmárkáknál, és a fenntartható divatról szóló diskurzus egyre szerteágazóbb lett a nagy mennyiségű adathalmaz miatt, amelynek egy része nem fedi a valóságot vagy félrevezető. De van köze mindennek a feminizmushoz? NAGYON IS VAN! Livia Firth a Vogue Arabia oldalán megjelent cikke nyomán ízlelgettük a témát.

A nők a ruhák és kiegészítők legnagyobb fogyasztói, és az ezeket gyártó munkaerő nagy része is nő (a ruhaipari munkások 80%-a nő). Az északi féltekén folyamatosan tüntetnek a nők jogaiért és egyenlőségéért, miközben örömmel viselnek olyan ruhákat, amelyeket a Föld déli részén már-már rabszolgasorba taszított és bántalmazott nők varrtak. Ennek így nem sok értelme van, ugye?

A „környezetbarát” divatmozgalom kezdete óta rengeteg női tervező mozog a divat élvonalában – Katharine Hamnett-től a nemrég elhunyt Vivienne Westwoodon át Stella McCartney-ig. Mégsem vontuk be soha a gyapotszedőket, a ruhaipari munkásokat és az ellátási láncban dolgozó nők millióit a párbeszéldbe. Miért? Mi lenne, ha másképp működnénk, figyelembe véve és tiszteletben tartva őket, és harcolva értük, mind a márkák, mind a fogyasztók szintjén?

Mi lenne, ha a márkák gondoskodnának arról, hogy a dolgozóik megkapják a tisztességes megélhetést biztosító bért, miközben tiszteletben tartanák emberi jogaikat? Lehet, hogy ez mindent megváltoztatna? Valószínű. (Ha te is így gondolod, írd alá a Good Clothes Fair Pay petícióját, vagy támogasd a kezdeményezést egy megosztással! Kattints ide a részletekért!)

Bethany Yellowtail indián divattervező gyönyörűen fogalmaz ezzel kapcsolatban: „Minden mindennel összefügg. Amit létrehozunk és ahogyan tovább adjuk azt, az a világra is kihat. Az iparágnak sürgősen a veszélyben lévő népcsoportok felemelésére, a közösség ápolására és a jövő generációit szem előtt tartó jövőkép kialakítására van szüksége. Valódi elmozdulás kell a méltányos együttműködés irányába. A B.Yellowtail márkámmal hozzájárulunk az indián művészek és vállalkozók kultúraváltásához. Generációkon keresztül csak azt láttuk, hogy a divatipar kizsákmányol minket és profitál belőlünk, anélkül, hogy ennek bármilyen következménye vagy haszna lett volna a népünk számára. Nagyon szép dolog látni, hogy egyre több bennszülött ember és közösség profitál a kreativitásunkból és ősi jogainkból.”

Üzenete hangos és világos, és a Good Clothes Fair Pay kampány mellett a Fashion Revolution Who Made My Clothes? mozgalmával is összecseng. Az elmúlt évek tapasztalatai alapján az emberek kíváncsiak arra, hogy kik készítik a ruháikat; ezen információ közreadásával személyesebbé és természetesen átláthatóbbá válnhatnak az ellátási lánc gyakorlatai.

Azonban még mindig nem vesszük észre, vagy nem törődünk eléggé azzal, hogy nőként prioritássá tegyük a többi nő támogatását a divat globális hálózatában.

Aurora James, a Brother Vellies és a Fifteen Percent Pledge alapítója szerint „a divattervezőknek, az összes többi, termelésen alapuló iparág vezetőivel együtt, tudatosan kell foglalkozniuk azzal, hogy mit tesznek és az milyen hatással van ez a világra”. Úgy véli, az iparágnak egy befogadóbb térré kell fejlődnie, és lehetőséget kell adnia azoknak, akiket a történelem során elnyomtak. Elmondása szerint ők gondosan kiválasztott, tehetséges kézművesekkel dolgoznak együtt, akik vezető szerepet töltenek be a saját területükön. „A fenntarthatóság azt jelenti, hogy olyan termékeket készítünk, amelyek tartósak, miközben tisztelettel bánunk egymással.” – tette hozzá.

Ugyanez igaz Angel Chang amerikai tervezőre is. „Egy lokális nonprofit szervezettel, a Tang’an Dong Etnikai Ökomúzeummal működünk együtt abban a kínai faluban, ahol a kollekcióink készülnek. Ők építettek egy műhelyt, egy festőüzemet és egy könyvtárat a közösség számára, mi pedig a kézművesekkel együtt dolgozunk. A világjárvány idején, amikor nem tudtam odautazni, a kézművesek elkezdték egymást képezni, így most már a műhelyünk teljes egészében kézműves irányítású! Az emberek gondoskodnak egymásról, és a termelés időzítését a saját gazdálkodási ütemtervük és az időjárás alapján koordinálják. A kapcsolatunk igazi együttműködéssé vált.” Chang számára fontos volt, hogy együtt éljen a helyi közösségekkel, hogy lássa, hogyan dolgoznak és mi foglalkoztatja őket…

Egy igazságosabb divatiparhoz alulról felfelé építkező megközelítésre van szükség, ahol a gyári munkásokat először megkérdezik, hogy mire van szükségük, majd erre az alapra építik fel a gyárat és a termelést.

Mkor, minek hataására fogunk végre felállni és tiltakozni? Mikor jön el az a pillanat, amikor már nem a ruháinkra leszünk büszkék, hanem az azokat készítő nők történeteire? Remélhetőleg nem kell még egy év, hogy rájöjjünk arra, hogy mi az igazi érték, mi az igazán értékes.

A 2023-as Fashion Revolution Weeken olyan programokkal készülünk, amelyek révén a hagyomány- és értékmegőrzésre hívjuk fel a figyelmet a divattal és a textiliparral összefüggésben, miközben a tradicionális és kortárs határmezsgyéjén mozogva felfedjük, hogyan lehet újragondolni az egyes ikonográfiákat, alapanyagokat, technikákat, bevonva a párbeszédbe a kézműves alkotókat és fiatal tervezőket egyaránt. Nagy hangsúlyt fektetünk továbbá a szakmai diskurzusra is, érdemes lesz velünk tartani, további információkért kövessetek minket social media felületeinken!

Kiemelt kép: Fashion Revolution/Samiull Alam

Van-e létjogosultsága az élelmiszeriparban már használt és jól bevált mintára épülő, GCA-típusú divatfelügyeletetnek? Egy ilyen szervezet létrehozása nem egyszerű, együttműködéseken, kutatásokon és a kormányok aktív részvételén alapul, de mit is takar valójában? Ennek jártunk utána a www.thegrocer.co.uk cikke nyomán.

A ruhaipari munkások kizsákmányolása hosszú és tragikus múltra tekint vissza. Már 2004-ben az Oxfam Trading Away Our Rights című jelentése is arra figyelmeztetett, hogy a szupermarketek és a ruházati márkák szisztematikusan visszaélnek az ellátási láncokban a hatalmukkal, hogy költségeiket és az üzleti kockázatokat a termelőkre hárítsák.

Az Aberdeeni Egyetem kutatói 1000 bangladesi gyárat vizsgáltak és megállapították, hogy a Tesco, az Aldi és a Lidl a legrosszabbak között vannak abban a tekintetben, hogy a világjárvány idején a termelési költségeknél is kevesebb pénzt adtak a beszállítóiknak, így azok alig tudták kifizetni munkavállalóik béreit. Az állításokkal vitatkoztak a vállalatok, de ez a kutatás további löketet adhat egy komplex divatfelügyeleti szerv létrehozásának, ami hasonlóan működne, mint a GCA (Groceries Code Adjudicator). Ez biztosítja, hogy a kereskedők jogszerűen és tisztességesen bánjanak közvetlen élelmiszer- és italszállítóikkal belföldön és külföldön egyaránt.

Nagy-Britanniában egyre többször kerül szóba ez a téma. A Westminsterben már 25 képviselő támogatta azt a törvényjavaslatot, amely a divatáru-kiskereskedők számára hivatalos gyakorlati kódexet hozna létre, amelyet egy szabályozó hatóság hajtana végre. Liz Twist képviselő tavaly júliusban mutatta be a törvényjavaslatot: „A Groceries Code Adjudicator [az élelmiszeriparban] drasztikusan csökkentette a visszaélésszerű vásárlási gyakorlatok elterjedtségét, amelyek egykor széles körben jelen voltak az ágazatban”, közben arra sürgette a kormányt, hogy mutasson példát egy hasonló koncepciójú divatfelügyelet létrehozásával.

Tényleg ez lehet a megoldás?

Az európai kiskereskedők nem teljes mértékben tehetők felelőssé egy sok ezer kilométerrel arrébb lévő gyár munkakörülményeiért, de a vásárlási gyakorlatukkal befolyásolhatják a fennálló körülményeket és kisebb-nagyobb változtatásokkal javulást tudnának elérni.

A ruhagyárak nagy hányadánál felmerülnek utolsó pillanatban történt lemondások, fizetési késedelmek, valamint az is probléma, hogy a vevők nem emelték fel az árakat a fogyasztók számára a gyártók költségeinek emelkedésének megfelelően. Ez azonban közvetlen hatással van a gyárak bérnövelési gyakorlatára. A képviselők és a kampányolók úgy vélik, hogy az élelmiszeripari felügyelőszervezet jó modellt kínálhat a divatiparnak, mivel az olyan kérdésekkel, mint a lemondások és a fizetési késedelmek, már most is foglalkozik ez a szervezet. A kutatások azt mutatják, hogy a GCA 2013-as létrehozása óta sikeresen visszaszorította a visszaélésszerű gyakorlatokat. Egy felmérés alapján 2014-ben a beszállítók 79%-a számolt be a szupermarketek által elkövetett szabályszegésekről. Ez az arány 2021-re 29%-ra csökkent.

Fiona Gooch, a Transform Trade vezető politikai tanácsadója szerint ahhoz, hogy egy divatfelügyelet hasonló sikereket érjen el, mindenképp rendelkeznie kell bírságolási jogkörrel. A GCA a nagyobb kiskereskedőket az Egyesült Királyságban elért forgalmuk 1%-áig bírságolhatja – ezt a hatalmat a Tesco is megérezte 2016-ban, amikor 1 millió fontos büntetést volt kénytelen kifizetni a beszállítóknak történő késedelmes kifizetések miatt. A büntetés mértéke a divatipari szereplőket is eltántoríthatja a tisztességtelen gyakorlatoktól.

A legfontosabb különbségek

A divat egyedi jellemzői azonban más megközelítést kívánnak. „Az egyik legfontosabb a kódex kiterjesztése a munkahelyi előírásokra, aminek a biztosítása a kiskereskedő felelőssége lenne, hogy a gyártó megfeleljen bizonyos kritériumoknak.” – mondja David Sables, a GSCOP szakértője, aki több divatmárkával dolgozott már együtt. Míg a GCA-t pusztán azért hozták létre, hogy biztosítsa a fair playt a tárgyalásokon, a divatszakmában ez nem lenne elegendő. Szerinte a mélyebb problémák miatt ennél tovább kellene mennie a szervezetnek, esetleg magába foglalhatná a kiskereskedők által már elvégzett gyári ellenőrzések hatáskörének kiterjesztését.

Mindez összetett és sok kihívást rejt magában. „Az Egyesült Királyság felügyeleti szerve, amely elsősorban a térség beszállítóival foglalkozik, még mindig azzal küzd, hogy sokan nincsek tisztában a kódex részleteivel. És ha nem ismerik, akkor honnan tudnák, ha egy kiskereskedő olyasmit tesz, amit nem kellene?” – mondja Ged Futter, a GSCOP egyik vezető szakértője és a Retail Mind igazgatója.

Elvárható-e tehát, hogy egy bangladesi ruhagyár megértse és betartsa egy 8000 kilométerre lévő ország szabálykönyvét?

Egyelőre a kampányolóknak egy sokkal sürgetőbb akadállyal kell szembenézniük az új szervezet felállításával kapcsolatban. A brit kormány igen óvatos, így elsősorban az a cél, hogy meggyőzzék azt arról, hogy a divatfelügyeletre valóban szükség van.

Mekkora az esélye tehát annak, hogy a brit kiskereskedelemre rászabadul egy divatfelügyelet? Sables szerint 20% az esélye a következő öt évben. „Nem fűzök hozzá nagy reményeket, de a világ minden táján dolgozó munkavállalókkal szembeni méltányosság szempontjából ez egy előrelépés lenne.”

Te mit gondolsz erről a témáról, szükség lenne a divatipar állami szintű kontrollálására?

Szerkesztette: Pölz Klaudia

Eredeti szöveg: ITT

In Addis Ababa, Amharic language filled its bustling crowded streets. The city’s smoggy air and high altitude of 2600m contributed to our difficult adjustment to limited oxygen. It was mid-May 2022, when we, a team of researchers from Drip by Drip, started our five week exploration of Ethiopia, “the rising star” in textile production.

Drip by Drip is a German-based nonprofit organisation that exists to tackle water pollution through the textile industry. Currently, we are working in Bangladesh on two different projects. For the future, we want to extend our impact into more countries that suffer from decreasing clean water resources, which led us to Ethiopia.

We set out to understand the current situation of Ethiopia’s textile and garment industry. In doing so, it was our goal to learn about the current political and economic situation and to understand whether Ethiopia will be the next Bangladesh. Additionally, through a three-week collaboration with Sequa gGmbH, an NGO funded by GIZ (German society for international cooperation) and UKAID, we had the opportunity to visit local factories, the Hawassa Industrial Park, and speak with a large international buying agency, which acts as a liaison between major brands and production facilities. We also conducted interviews with stakeholders, which included local and foreign factory managers, factory employees, NGOs, B2B customers, ministry staff, and entrepreneurs. To protect the identity of the interviewees we will not disclose their names.

The Rising Star

Our preliminary research depicted Ethiopia as a budding force in textiles, with the potential of competing against China’s and Bangladesh’s industry. However, we quickly discovered the lack of validity and substantiality in our online sources. The lack of data brought up questions about Ethiopia’s labor costs, work environment, industrial waste, access to water, infrastructure, investments, foreign connection, the security and health system.

In 2020, the Economic Intelligence Unit, predicted an economic growth in Ethiopia of 7% .(1) In comparison to other African countries, whose common growth rate ranged from 2%to 3%, Ethiopia appeared to be advancing faster. Additionally, the International Monetary Fund predicts an increase in their gross domestic product (GDP) from 3.84% in 2022 to 5.72% in 2023, 6.23% in 2024, and so on.(2) On top of this, Ethiopia has a population of roughly 110 million people, with an expected growth rate of 2.49%.(3) A country with an exponentially growing population offering a plethora of job opportunities with no legal framework of a legal minimum wage is an attractive option for investors. Because: A growing population ensures investors a growing workforce. Additionally, Ethiopia offers low labor costs. Where there is a low labor cost, you will commonly find textile and garment businesses. The average pay wage for garment workers range from $340 to $95 per month, while in Ethiopia, the pay wage is set at $26 per month.(4) This causes a slow and silent factory shift from China, Vietnam and Bangladesh to countries like Ethiopia. Last but not least, the war that began in the Tigray region in the north of the country about a year ago and has spread to more southern regions.(5), is having a destabilising effect on the entire country.

Ethiopia’s Export and Import Dilemma

To investigate further, we scheduled meetings for the first two weeks of our exploration with stakeholders in the field of environmental science, textile production, and business management. Stakeholders included locals, professors, consultants, activists, businesspeople, and fashion designers. Our preliminary research depicted Ethiopia on the cusps of a new era as they transitioned from a developing state to an industrial state, but it became evident that we drastically underestimated the situation. With every conversation, the illusion of the “rising star in the textile industry” vanished. Under former Prime Minister Zenawi Haile, the Ethiopian government pursued a Growth and Transformation Plan, which expired in 2020. This plan pursued various targets, one of which was the development of industry. Under these targets, 13 industrial parks were established for different manufacturing industries – the textile and garment industry were one of them.

Industrial parks (IPs) are portions of a city zoned for industrial use. Through the construction and promotion of IPs, Ethiopia approached investors and companies to establish themselves at industrial parks; unfortunately, with no long-term success. We learned from an Indian-owned garment company that their production capacity has shrunk by 50%. Adding to the dilemma, the US terminated the AGOA agreement, which forced the closure of many factories. The African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) is a US agreement that allows AGOA member countries to export duty – free and tax – free to the United States. Ethiopia has long been a member, but in November 2022, Biden terminated that alliance on the grounds that Ethiopia harbors “violations of international human rights.” Such termination caused major producers and fashion companies, such as the PVH Group, to halt production in Ethiopia. With AGOA, companies exported 60% – 80% of their goods. Since its termination, exports have shrunk to 20% – 30%, along with a decrease in the country’s number of textile companies. We visited the industrial park in Hawassa, the largest IP hosting 52 halls that are now mostly empty due to the AGOA termination. Hawassa’s IP stood as a foreshadow or a glimpse into the future for many foreign investors, especially from India, China, Bangladesh and the US.

During AGOA, a majority of Ethiopia’s goods were exported to the US. Now that AGOA has ended, factory owners want to focus on the EU market. The EU is a more complicated venture though, as it has more regulations and requirements than the US, such as certifications like CmiA, OEKO-TEX Standard 100 and SteP or the BSCI. For Ethiopian textile companies, this would mean a new type of commitment.

Exporting and Importing with an Ethiopian-Owned Factory

We often came across non-certified Chinese, Indian or Sri Lankan operated factories that usually import their cotton from China or India. Fortunately, we were able to visit an Ethiopian – owned textile production site located in Kombolcha, about an hour flight from Addis. Kombolcha Textile Share Company is a 100% Ethiopian operated factory that uses 100% Ethiopian cotton and has a water treatment plant. The factory is also OEKO TEX SteP and ISO 14001:2015 and ISO 9001:2015 certified – a real rarity in the Ethiopian market. The factory owner of Kombolcha Textile informed us about his problems with importing chemicals, dyes, or spare parts for machines. Since Kombolcha Textile is a certified company, he is obliged to use certified chemicals, but Ethiopia does not produce those. In the past, he purchased his dyes from a Swiss company that had stores in Ethiopia. Unfortunately, the Swiss company closed its stores, which means the factory owner must now import all those goods. To pay for and import goods from abroad, an Ethiopian company needs foreign exchange (forex). Foreign exchange is one of the biggest challenges of the industry. Unlike Euro (EUR) or US Dollar (USD), Ethiopian Birr (ETB) is not an official trading currency.

We learned about Ethiopia’s foreign exchange issue from a GIZ employee. To understand the following example, let’s define two terms:

● Export turnover is the sale proceeds or a company’s earnings from their exported goods.

● Foreign exchange (forex) is trading one currency for another.

So, if an Ethiopian company’s export turnover, or earning amount, is 100 EUR. 80% of their earnings will be converted to ETB and 20% will be converted to forex. This leaves them with 80 ETB and 20 EUR. Then, 80% of that 20 EUR must be given to the Ethiopian government for forex taxes. This means that the company has only 4 EUR remaining. Remember, ETB is not an official trading currency and they are not allowed to convert the 80 ETB to EUR or USD. Therefore, the company can only use the remaining 4 EUR to import goods. Needless to say that 4 EUR is not enough to import goods from abroad. Therefore, the instability of import and export costs makes it nearly impossible for smaller companies to survive, especially when they rely on a small amount of forex.

On top of this, the cost of homegrown cotton increased significantly in Ethiopia. In comparison, the Indian cotton price is 2.10 USD, which is about 109 ETB per kg, and the Ethiopian cotton price is 130 to 150 ETB and rising. As a result, many small local factories, like Kombolcha Textile, now use their own stock of cotton for production, which will only last for another 6 months. Overall, we discovered that the priorities of the industry are on one hand export growth and on the other hand employment growth. When it comes to water management, a very complex issue, there is a lack of focus on water supply and sanitation for both large industries and local manufacturers, which led us to the next challenge.

The Water Problem

We had the pleasure of speaking with professors from a highly renowned university in Ethiopia. They shared with us Ethiopia’s rich water history that gave the country its nickname – the “Water Tower” of Africa. A local friend informed us about Ethiopia’s government-supervised water meters for private households. These meters are read monthly and consumption must be paid accordingly. Unfortunately, this is not the case for industries. Through a conversation with a consultant from an Environmental Consultancy Service, that proposes for environmental reform to the Ministry of Industry as well as the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, we learned the following about industrial water consumption:

IPs are built by the government, and foreign investors rent out the space and use it for production. Foreign investors pay for rent and electricity, but water is free. They are allowed to drill their own water boreholes and are not required to prove consumption. Additionally, treatment of wastewater is recommended, but not required for production. Therefore the consultancy company advocates for more regulations surrounding wastewater decontamination and water extraction.

An employee from an Indian – owned textile company spoke with us about their wastewater system and treatment plant. They installed their wastewater treatment plant a year after the company opened. It is designed to treat chemicals and dyes so that the wastewater can be recycled back into the company’s water cycle. However, the plant did not have the capacity to treat the amount of wastewater produced. So, up until 2 years ago, production simply discharged their excess wastewater, especially in the rainy season, to the surrounding fields. Farmers from the surrounding areas rightfully complained about the issue, and the government gave the company a warning. Since then, wastewater has not been discharged, but no solutions about the contaminated fields, which still release an acrid smell, have been discussed. Then, another issue came up. It was further explained that when the water goes back into production to be reused, 10% is left as compressed sludge residue in the form of granules. The company produces 5 bags of granules per day. These bags were simply disposed of in surrounding areas. The government then required the company to store the bags, which are now kept in a warehouse onsite, but there is no solution for its final disposal.

Conclusion

Without the warmth and hospitality of the Ethiopian people, we would not have been able to learn anything about textile production. The biggest challenge for us was the access to data, because especially in the area of water there are almost no reliable surveys. So the personal conversations with the different stakeholders were essential for our assessment. Ethiopia clearly has the potential to become the next “rising star” in the textile industry. However, the political and economic challenges are still too great at the moment. Therefore, we leave the country with mixed feelings. Ecologically, it remains to be feared that the uncontrolled water extraction by the industries, as well as the growing interest in local cotton cultivation, will lead to a significant shortage of clean groundwater. For the economic situation of the unemployed population, on the other hand, the IPs could be a long-awaited blessing. Similar to Bangladesh, positive effects on the emancipation of women can also be expected. A dichotomy that can be resolved: An early enactment of laws regulating the use of water as a resource throughout the production cycle. Because without clean water, even the greatest economic boom cannot prevent another humanitarian crisis. We will continue to follow the developments with great interest.

A report by Charlotte Kühl & Michelle Dixon for Drip by Drip

Charlotte Kühl is a student for clothing technology and fabric processing. During her involvement with Drip by Drip as a working student, she went on a seven-week research trip to Ethiopia, to analyse the status quo of the textile and apparel industry. This article is a summary of her findings.

Michelle Dixon is a writer and visual artist with an interest in fashion and water pollution. She holds a Master of Arts in Nature – Culture – Sustainability Studies and her research encompasses fashion and agriculture, fashion and water security, and fashion and grace. She is a researcher and project assistant at Drip by Drip.

The copyright for the pictures belongs to Charlotte Kühl.

Further reading

Fashion’s opportunity to be a force for good

Fashion’s role in fighting human trafficking, reducing vulnerability, and uplifting humanity

Beyond Compliance in the Garment Industry

Desde Chile nos unimos a Clean Clothes Campaign

Esta campaña internacional busca mejorar las condiciones de trabajo y apoyar el empoderamiento de los trabajadores de la industria mundial de la confección y la ropa deportiva, ayudando a que se garanticen sus derechos fundamentales y laborales.

Clean Clothes Campaign (CCC) es una red mundial dedicada a mejorar las condiciones de trabajo y empoderar a los trabajadores en las industrias mundiales de la confección y la ropa deportiva. Se fundó en los Países Bajos en 1989 con el nombre de Schone Kleren Campagne.

Hoy en día, esta campaña reúne a más de 230 organizaciones en 45 países, donde se incluyen: sindicatos, grupos de mujeres y feministas, organizaciones de trabajadoras domiciliarias, ONGs de defensa del consumidor, entre otras. Estás organizaciones se encuentran presentes tanto en los países productores de vestuario como en los de mercados de consumo.

Para hablar más en profundidad sobre esta campaña, su relevancia de carácter internacional y cómo podemos sumarnos e invitar a otras y otros a ser parte, nuestra colaboradora María Teresa Flores conversó con Ilana Winterstein, Urgent Appeals Campaigner de Clean Clothes Campaign en Países Bajos.

¿Por qué necesitamos esta campaña?

La industria global de la confección se basa en la explotación de los trabajadores de la confección, en su mayoría mujeres del sur global, ya que las marcas aprovechan la mano de obra barata y las leyes laborales laxas para maximizar sus ganancias. Hay poca transparencia y casi ninguna rendición de cuentas en la industria. Cuando se descubren violaciones de los derechos humanos en las cadenas de suministro de las marcas de ropa, hay pocas o ninguna repercusión en la marca. A menudo, las marcas simplemente niegan su responsabilidad y no hacen nada al respecto.

La desigualdad en la industria es extrema, las marcas obtienen ganancias de miles de millones, mientras que los trabajadores de la confección que fabrican sus productos ganan salarios de pobreza que apenas cubren sus necesidades esenciales, trabajan muchas horas y, a menudo, en condiciones inseguras.

El Covid-19 ha exacerbado esta situación. A millones de trabajadores no se les han pagado los salarios y las indemnizaciones por despido que legalmente se les deben desde que comenzó la pandemia. CCC estima que los ingresos de los trabajadores de la confección a nivel mundial se redujeron en $11,85 mil millones de dólares solo durante los primeros 13 meses de la pandemia. Muchas marcas, por otro lado, han aumentado sus ganancias durante la pandemia.

La forma en que opera la industria muestra que hay una desconexión entre las marcas y los trabajadores que fabrican sus productos y vacíos legales que permiten a las marcas dar la espalda a los trabajadores, incluso cuando legalmente se les debe salarios o indemnizaciones por despido.

El cambio estructural en la industria está muy retrasado y las marcas, que tienen todo el poder en la industria, finalmente deben rendir cuentas por los abusos en sus cadenas de suministro. Esto es lo que CCC trata de hacer, asegurando que las voces y demandas de los trabajadores sean centrales en las discusiones sobre el cambio.

¿Cuál es el principal desafío?

Es difícil identificar un solo desafío cuando se necesita un cambio estructural en la industria. Necesitamos con urgencia una legislación que haga que las marcas se hagan responsables. En este momento, la industria depende en gran medida de las iniciativas voluntarias para proteger los derechos de los trabajadores, pero estas iniciativas fallan rotundamente en hacerlo y se ha demostrado repetidamente que no son adecuadas para este propósito.

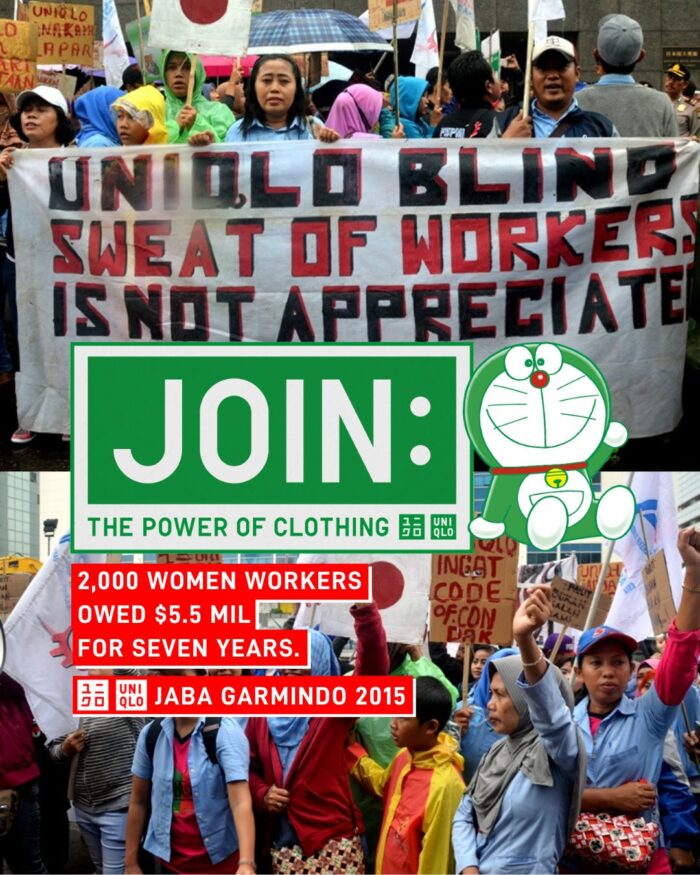

Una de nuestras principales campañas en este momento es Paga a tus Trabajadores – Respeta los Derechos Laborales (Pay Your Workers – Respect Labour Rights), que cuenta con el respaldo de decenas de sindicatos de trabajadores de la confección en los principales países productores de indumentaria, y cuenta con más de 260 organizaciones que lo respaldan, incluidas organizaciones laborales y de derechos humanos.

Las marcas hacen todo lo posible para evitar ser responsabilizadas y el modelo actual funciona a su favor. Hará falta un gran impulso mundial para que firmen un acuerdo vinculante que garantice salarios e indemnizaciones por despido, ¡pero juntos podemos lograrlo!

Educamos y movilizamos a los consumidores, presionamos a las empresas y los gobiernos y ofrecemos apoyo solidario directo a los trabajadores en su lucha por sus derechos.

Alguien que viva en Chile y/o en Latinoamérica, ¿cómo puede sumarse a la campaña de CCC?

¡Sí! Necesitamos una acción global para presionar a las marcas y demostrar que existe un deseo común de que respeten a sus trabajadores y protejan los derechos humanos. Muchas de las marcas sobre las que hacemos campaña se venden a nivel mundial, como Adidas y Nike, que son objetivos de la campaña #PayYourWorkers y #RespectLabourRights. Sabemos que el apoyo mundial realmente puede marcar la diferencia.

Cada vez que alguien firma una petición, realiza una acción en línea o protesta fuera de una tienda, ayuda a difundir la conciencia y mostrar a las empresas que queremos un cambio. La solidaridad del consumidor también ayuda a lograr victorias que cambian la vida, como el caso reciente de la fábrica Brilliant Alliance en el que más de 1250 trabajadores en Tailandia ganaron $8,3 millones en salarios atrasados de la marca de lencería Victoria’s Secret, en lo que fue el caso más grande de robo de indemnizaciones por despido en una sola fábrica de vestuario.

La pandemia ha destacado lo interconectados que estamos todos y es hora de usar eso para movilizarnos en conjunto. En la solidaridad, hay poder y cuando trabajamos juntos colectivamente para desafiar un status quo desigual e injusto, podemos hacer que el cambio suceda.

¡Revoluciona con un clic!

La invitación es a ser parte, siendo un/a revolucionario/a desde cualquier parte del mundo.

Puedes seguir las redes sociales de Clean Clothes Campaign (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, LinkedIn) para conocer las próximas acciones.

También puedes visitar su sitio web que tiene mucha información para crear contenido y unirte a esta campaña desde tu activismo personal o emprendimiento. Otra opción es suscribirse al boletín de noticias para obtener más información.

La campaña Pay Your Workers está respaldada por más de 260 organizaciones. ¿Quieres que tu organización se una? Puedes hacerlo si eres parte de una organización que está interesada en respaldar la campaña y apoyar las acciones, sigue el enlace aquí https://crm.cleanclothes.org/node/81

This is a guest post by Outland Denim, a business founded to offer opportunity, financial freedom, education, and support to women who have come from backgrounds of human trafficking, exploitation or vulnerability.

Header image: Cesar López

The impacts of Human Trafficking are widespread, and you’ll often see its prevalence illustrated in statistics (you’re about to read many in this article). But we can’t be reminded enough – these are real people, not figures. So we start this article with an excerpt of Chandramma’s story, published here on Fashion Revolution by International Justice Mission.

“Chandramma was offered work at a silk farm. But what looked like a chance for stability and a better life for her young family, was in reality a job under false promises. She tried to escape twice, but both times she was caught, brought back and beaten up.

She was punished, and trapped for 6 months in this hot, dark jail cell, with little food and almost no water… She and the other labourers were forced to work for 15-16 hour days twisting silk threads with one short break for food.

With the help of IJM and local authorities Chandramma’s story ended with her being found and freed.”(1)

Today, Chandramma is a wedding planner, a community advocate against forced labour, and is able to provide for her family.

She is just one of many impacted by this USD $150 billion industry.(2) That’s over twice the size of the USD $66 billion denim jean industry.(3)

In recognition of the UN’s World Day Against Trafficking, held annually on 30th July, we’re exploring trafficking’s connection to fashion and how some brands are supporting survivors with the help of your purchase.

Human trafficking is just one form of modern slavery, which is used as an umbrella term for different forms of severe exploitation, which also includes forced labour and forced marriage, and affects an estimated 40.3 million people globally.(4)

Who is most impacted by human trafficking?

Overwhelmingly, women are more likely to be vulnerable to human trafficking. In 2018, approximately 70% of identified victims were female, more specifically 50% women and 20% young girls.(5) To put this in perspective, one in every 130 women and girls globally are a victim of modern slavery.(6) So this is a very gendered issue.

People who have limited access to employment are particularly targeted. In fact, the United Nations identified that economic need was the greatest pre-existing factor to cases of identified trafficking, existing in 51% of cases.(7)

So how does human trafficking relate to the social injustice we see in fashion?

The garment industry is just one of many where trafficking in the form of forced labour, and the broader issue of modern slavery, can be found.(8)

Even where not categorised as forced labour, human rights abuses and work insecurity are rife in the garment making industry, further perpetuating cycles of economic vulnerability in individuals, particularly women, their families and communities.

To speak to economic stresses alone, approximately 1 in 8 working people rely on the fashion industry for their income, and yet only about 2% earn a living wage.(9) A living wage is a crucial protective mechanism against the scourge of modern slavery, human trafficking and exploitation.(10)

View this post on Instagram

Defining Forced Labour