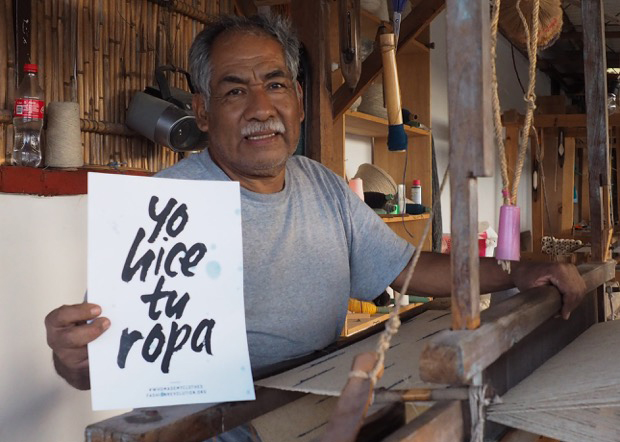

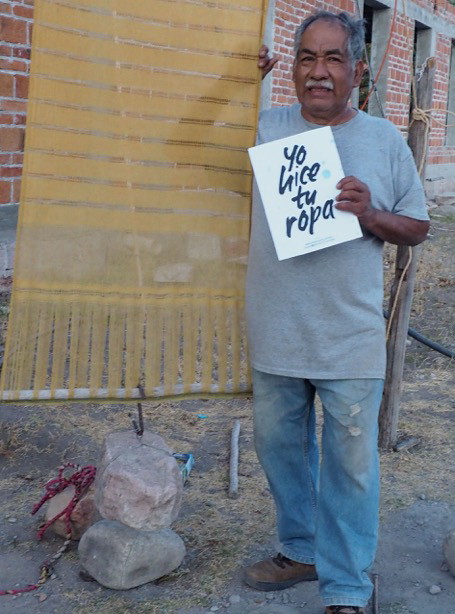

Carry Somers meets Don Arturo Hernandez at the Bia Beguug workshop in Mitla, Oaxaca, Mexico, to investigate the slow process of making a naturally-dyed, hand-woven rebozo shawl.

The earliest textiles in this region were made from the maguey cactus which, contrary to what you might expect, can produce a very delicate, fine fibre for weaving clothing, as well as a strong fibre traditionally used for bags, hammocks and fishing nets in Mesoamerica. At Bia Beguug, their rebozos are made from sheep’s wool and from cotton.

Sheep were introduced to the Oaxaca region by the Spaniards in 1521, along with the two-pedal harness loom. The Zapotec people disliked the Aztecs and so the Spanish friars found a reasonably sympathetic welcome. The Spaniards needed wool garments and horse blankets, and the sarape blankets were exported from these communities all over Mexico.

Don Arturo also uses locally-grown cotton, both the white Mexican criollo cotton which was introduced by the Spaniards, and the indigenous prehispanic coyuchi cotton. Scientists have found cotton fibres dating back 7000 years in caves near Mexico City.

If making a wool rebozo, the sheep’s wool is first spun and wound into skeins before dyeing.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GpaV7th7Rm0

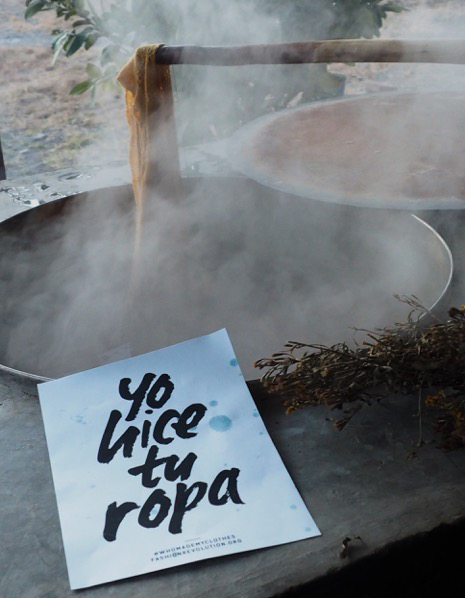

Today, Don Arturo is dyeing with pericone, wild marigold. As well as producing a beautiful golden tone, wild marigold also acts as a natural mordant. Don Arturo will heat the wild marigold for a minimum of twelve hours. He has to keep checking it all day, ensuring it doesn’t boil and adding more kindling, wool and dried cactus leaves, to the fire. Three kilos of dyestuff will dye twelve 2-metre rebozos.

As well as wild marigold, he dyes with añil indigo, cochinilla cochineal, granada pomegranate and pino pine. He will also use nogal walnut, both the shell, which produces a wide range of colours from reds to browns, and also the leaves.

When dyeing other colours, such as cochineal or indigo, a mordant is needed. Don Arturo tells me:

“No hay nada mejor que el orine de niño” (There is nothing better than a boy’s urine for acting as a mordant)

His grandparents used this method and Don Arturo would like to use it, but says that customers don’t want to buy something which has been in contact with human urine, so he now uses Alumbre de potasio, potassium alum, and will also use ceniza or wood ash, left from the fire after heating the dyebath.

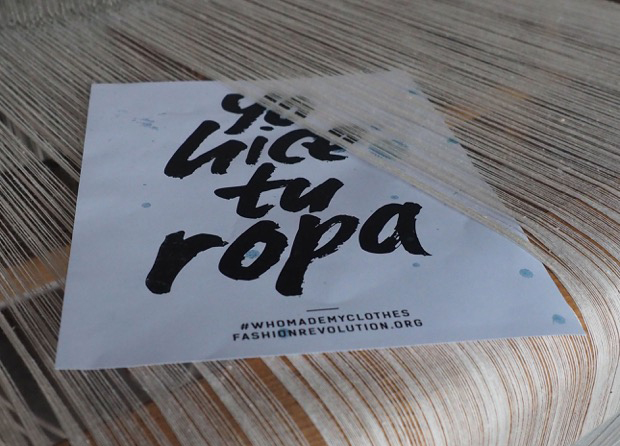

The next stage is the weaving. First the warp will be prepared. The warp is the set of longitudinal threads which are kept under tension on the loom.

Weaving is an ancient Zapotec tradition – before the Spaniards introduced the pedal loom and flying shuttle loom, the backstrap loom was widely used throughout Latin America and is still used in many communities today. Alejandro (below), Jesús, Arturo and Felipe are skilled weavers and can weave a rebozo in just two hours.

Once woven, the finished shawl is washed with a natural soap and then left to dry and release any grease for one day.

The final step is to add tassles to the end of the shawl, a job which the women often do at home while looking after their children.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vMwTf3GIBGA

Natural dyes are the antithesis of fast fashion. They produce a surprisingly wide range of colours. We have been using naturally dyed silk on our Panama hat collections at Pachacuti for the past few years and I have been astonished at both the intensity and the subtlety of the colour range.

In her 1972 book The Use of Vegetable Dyes Violetta Thurston says:

No synthetic dye has the lustre, that under-glow of rich colour, that delicious aromatic smell, that soft light and shadow that gives so much pleasure to the eye. These colours are alive.

Although natural dyes, just like analine dyes, have the potential to harm the environment, both in the collection of the dyestuffs from fragile environments and in the environmental consequences of releasing dyes and mordants into water supplies, all of the dyers I met in the Oaxaca region were very conscious of both sustainable harvesting and disposal.

They won’t provide a solution for the toxic chemical devastation caused by the garment industry in many parts of the world – we will need to look to waterless dyes and other future innovations in the dye industry to see the mainstream become more sustainable.

Hand-weaving can be a source of sustainable livelihoods around the world, particularly in rural areas, from India to Mexico. But hand-weaving doesn’t satisfy the demands of an industry requiring perfect thousands of metres of identical woven cloth, or indeed of customers unused to the odd small irregularity in the weave. We take no joy in the character of the cloth from which our clothes are made. We don’t see imperfection as a sign of the hand of the maker, but as a flaw to be eliminated from the production process.

One rebozo takes 3 days to make in total, from the preparation of the dyestuffs to the final shawl. This is fashion which draws on history and heritage. This is fashion with the odd irregularity, both in the dyeing and the weaving, and in my eyes it is all the more beautiful for it.

And maybe things are slowly changing in the fashion world. Faustine Steinmetz, who is quoted as saying that she was ‘keen to rebel against things that were flat’ showed her AW16 collection at The Tate yesterday. The textural qualities of the fabrics only served to enhance their craftsmanship.

Hunger TV said,

By returning to the very beginning, weaving the fabrics by hand rather than sourcing them from somewhere else, every element of the design process is laid bare, allowing us to have a true and raw understanding of the garment. This is wear the true ingenuity of Steinmetz’s work lies in it’s honesty.

I hope this may just be the start of a wider celebration of the honesty, tradition and skill of naturally-dyed and hand-woven fabrics. Let’s celebrate their character. It’s what makes them, and their wearer, unique.

If you are in the Oaxaca region and would like to visit the Bia Beguug workshop, I recommend signing up for Norma Schafer’s natural dye and weaving tour.

To continue to grow Fashion Revolution as a global movement for change, we need your financial support. Even the smallest donation will help us to continue delivering the resources we need to run our revolution. Please donate, be a part of this movement and help us keep going from strength to strength. We can, if you help.

Ding (left) explains his life philosophy to researcher Mikaela Kvan (right) stating, “I will work until I can’t. That is how I will live my life.” Photo by Daniel Huang

Shenzhen developed earlier than other cities in China so there were many more opportunities to find work here when I first arrived. I came here along with other migrant workers. I didn’t think I would stay here for long but it ended up being 20 years. I have been in Shenzhen for 22 years. Before I married, and when I was young, I lived in cities all across China. I am originally from Jin Jiang in China’s northeastern Jiang Su Province. I go home once a year for the Spring Festival.

I work in garment factories pressing clothes before they are packed for distribution. I’ve had this job on and off over the course of my life. My very first job was as a presser. Soon after, I graduated to a managerial position doing logistics for 20 years. Now I am back to my old job. It’s harder but I have more flexibility and less pressure.

My wife doesn’t live here with me. We used to live together but, when our daughter started junior high school, my wife left to be with her. Our daughter’s teacher called to tell us she was not doing well in school. As parents we want our kids to have a better life than we do and we want them to achieve something. I don’t want her to end up doing physical labor like us.

Now our daughter is 28th in her faculty at university. I am relieved to see her doing so well. She is a good kid and I am proud of her. She studies information engineering at Nanjing University. I’m not sure what her future holds, because it is up to her. She may not be able to make a lot of money because getting rich partly depends on luck.

Earlier this year she was selected as one of ten students to study abroad in America. There was a test to select those ten students. Those who aced the test could go. The school will pay for half of the expenses and we will cover the other half. So far, my wife and I can afford it. We are a bit strapped for cash, but I haven’t worked excessively because health is also important to me. If there are orders coming into the factory and us workers have the opportunity for lots of overtime then I can just stay here. However, if there is no overtime at this factory then I will go to other factories to do the same work. I just don’t take any days off. That includes Sunday. I see a bit of myself in my daughter. She is hardworking.

The reason I stay so disciplined in my work is my child. I want to provide for her. I believe you can do anything you want as long as you have money, but you can’t do anything without money. When my kid finds a job, builds her own family and everything is settled for her, only then will I go back to my hometown. I’ll find a job there so my kid doesn’t have to support me. I don’t want to burden her and I want to lift some pressure from her shoulders. I will work until I can’t. That is how I will live my life.

This interview has been edited. It was originally conducted on July 13, 2014, in Yantian, an industrial area east of Shenzhen, China. Read the full story here

Primary Voice is a collection of primary source interviews dedicated to documenting the living stories of garment factory workers worldwide. It was created by urbanist Mikaela Kvan. To read more interviews and to get in touch visit www.primaryvoice.org

Meet Margaret Kadi, creative inspirer at WORN

Recently we embarked on a journey behind the seams and met some of the local artisans working on the WORN initiative, a social venture that invests in communities worldwide to bring empowerment and education to children and young adults. Using precious recycled textile collected through various channels in Europe, the Artisans upcycle the materials into new and unique products. We catch up with Margaret Kadi, Founder of Project Sierra Leone and Pangea and Creative Inspirer at WORN to find out about herself and her work at the social enterprise.

Margaret was born in Sierra Leone but moved to London in the early nineties as the civil war began to break out across the country. She jumped on the education ladder at University in London and later worked in broadcast media for 12 years. She expresses with great sadness that she never made back until 17 years later when she visited for a two-week holiday – She was completely blown away. There was a buzz in the air and opportunities everywhere even though it is one of the poorest countries in the world. The people on the other hand are the warmest of people you would ever come across, as they are so welcoming.

Her shop soon became the go to shop for gifts and fashion accessories and things were great for about a year until the Ebola hit the country heavily affecting local businesses and entrepreneurs. The cloth weavers are based in remote villages so it became a logistical nightmare to get the goods to Freetown when most areas were under quarantine.

“My biggest passion is continuing to create a sustainable business where empowering Sierra Leoneans is at the core of what they do. The original idea was to work with predominantly women but that quickly changed, as they wanted to have an inclusive and fair business where anyone can come in and train. Poverty is rife in Sierra Leone and it affects everyone so it only makes sense to train and work with as many people as possible. My one pre-requisite though is that they have a strong work ethic.

There are many moments of happiness in life but mainly when a client tells you that you surpassed their expectations, be it with a custom piece of furniture or a tailored dress. I also love it when customers find it difficult to believe that all our products are made in Sierra Leone. They admire the quality and standard so I hope we are changing the minds of some people who think locally made means poor quality…you could not be more wrong. I feel like our customers are our ambassadors because they give us really good feedback and ideas from things they see on their travels.

I have always been creative in that I have always had my own style. Trends have never been a big hit with me and I never like wearing what everyone is wearing so I always found ways to creatively customise my clothes and accessories. When I was at University I used to shop from charity shops and blend my finds with designer wear.

Sierra Leone like a few other countries is a really challenging place to be an entrepreneur. There is just so much to worry about. Having an idea is the easiest part but then you have to worry about where to get capital from to get things going. The interest rate on bank loans is extremely high so that deters a lot of great ideas coming to light. In my case, assembling a great team that understand your vision is terribly hard so you find yourself having to micro manage everything as I am a stickler for extremely high standards.

WORN is a wonderful initiative, especially as consumers are all about slow fashion and up cycling. I honestly think it could be the start of something big – I cannot wait to see if get off the ground. What we concentrate on is the transparent supply chain. This is absolutely imperative for any sustainable business and it gives the consumer added confidence that they are making the right decision to make a purchase. Secondly, I think it expands the mindset of the artisans who are not used to working within certain perimeters.

When asked on her advice to young entrepreneurs there was one thing she stuck by – Never give up. Believe in your ideas, if you do then its a lot easier to get others to see your vision. Get a mentor if you need to, perhaps someone doing something similar so they can guide you every step of the way until you are ready to unleash your idea to the world!

The Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone affected every industry and the country as a whole as you can imagine. We are slowly getting back on our feet so things are not too bad. Our hope is to increase our collective of artisans by bringing in more, especially women that were affected by Ebola. We’ll train them in jewelry making, batik making and business skills so hopefully they can set up their own respective businesses.

There is a good crop of creative of artisans in Sierra Leone. Once you find one, they will lead you to the rest. I am so grateful for the group we have, as they are the best at what they do. The arts and culture scene is not big here so you would never get to hear about them otherwise. For us it is imperative for you to know the hands that touch and make our products. When you come into our store you will see beautiful products, two tailors working away on orders or one of our jewelry makers making a piece of jewelry. There is a greater appreciation for the products when you get to see and know the person responsible for the products you own so dearly.

We have big plans for the future. We’d like to open a training school/center where we can encourage people to come in and learn a trade – whether it is furniture making, jewelry making or tailoring. I think something like that is so desperately needed in Sierra Leone as there is a huge unemployment problem that we hope we can play our part in addressing this issue.

We have a few collaborations with some great brands so we look forward to sharing this with you in due course.

By Luke Meredith, Founder & Chief Inspirer, WORN

Channa needs to spend over 300USD per month on food to feed her four children, chronically ill elder sister, husband and herself. Photo by Sok Chanrado

I’ve lived in Phnom Penh since 1992. My hometown is in Prey Veng Province. Where I used to live in the countryside, it would flood every year. I couldn’t find food to eat and I was an orphan. I moved to Phnom Penh to live with my sister so that I could work at a factory to feed myself. Phnom Penh had and still does have many more job opportunities than my hometown. I like living here for that reason.

The things I value most in life are having enough food to eat, and living together with my children and husband. I want to be able to send my kids to school everyday but financially I can’t. Simply speaking, when you don’t have money you cannot do anything. If I want my kids to go to school I have to look after my younger daughters, but then I can’t go to work.

My husband is a construction worker. Both of our wages combined are not enough to live off of. Plus, I have another mouth to feed – my elder sister. When her health is good, she will help out by taking care of my younger kids. If she doesn’t feel well, my elder sons must take care of their sisters and cannot go to school.

Despite our best efforts, things haven’t worked out the way we wanted. For example, in 2012, when my youngest daughter was born I couldn’t work and I didn’t have anything to eat. I had a big fight with my husband. It’s normal for a couple that lives together to argue often. After our fight one of my friends asked me to move to the border of Cambodia near Thailand but I didn’t go. I decided to go to an orphanage to ask for a place to stay instead. They did not let us stay. I didn’t know what to do, so I sold all of my stuff from living in Phnom Penh. If you can’t work you can’t live. I thought if we were in the provinces people would help us out so we moved to Sompov Loun for about five or six months. But then my kids became allergic to the land there. I didn’t know what to do. I asked another orphanage to let my kids learn at their school but my kids weren’t accepted because they weren’t orphans.

In my opinion, if your kids are educated they will think about and respect you as a mother. I have seen kids on my block beat their moms, cursing them. Kids nowadays have no manners or respect whatsoever. I hope and believe my kids, whether they are educated or not, will think about me as a mother and I can depend on them in the future. If they are educated though, I believe I can depend on them more. My 14 year-old son is a good kid. He does house chores, looks after his sisters and listens and obeys well unlike rich kids his age. I think a kid from a humble family is better than a rich kid in terms of character.

I believe my kids would have a bright future if they could go to school regularly though I cannot afford for them to do so. Think about it. I have to spend 10,000 KHR (10 USD) – and it’s not that small of an amount – everyday for food. So my monthly expenses for food is 300,000 KHR (300 USD). Not to mention, I have to pay for rice, utilities, rent, and so on. If I let my kids go to school regularly, I cannot make it at the end of the month.

My kids want to learn English, but I cannot let them. All I can do is buy a book for them to learn at home. I asked the teacher whether my kids were smart in school and they said my kids were the best. Both of my sons are the best. It’s my sin from my past life that I cannot afford for my kids to go to school. But unlike other mothers who do not care about their kids’ progress in school, when I get home from work, I always ask my kids what they learned that day. Since I have no inheritance for them, as a mother, that’s all I can do for them.

I think about my life all the time. My mother passed away when I was young, just six months after giving birth to my younger sister. I thought I would never get married if I couldn’t make enough money. We came to Phnom Penh after I reached puberty and my sister was a bit bigger. Our financial situation was better because my sister was working. But then I got my first abortion and got married. After that, my father died and my older sibling sold our land. That was when I had another abortion, my third child. We’ve been poor since then. I’ve been praying to god asking for help but nothing happens.

Yesterday or the day before yesterday, the school called for a parent-teacher conference. I went and they asked why my kids have stopped coming to school. I told them it was because I was poor. And then they asked why I became a parent if I had no ability to raise a child. I replied, “What was I supposed to do? I tried my best but it didn’t work out. Should I just rob or steal to make it happen?”

For example, when he gets his paycheck, he knows I need the money, but he only gives me some. You know men nowadays; needless to say, they are…tears come to my eye when I try to talk about this. My sister lives with us and he’s not happy about it. That is why he always picks fights with me. He is also younger than me. He’s still young and beautiful. That’s why. He loves his kids though. He hangs out a lot outside with his friends and stuff, so he always finds faults in me, but he never beats me.

I had a fiancé who was a widower before I met my husband. My husband worked on the construction near my factory. One day he asked me for some water. Then he touched my hand and I was like, “Why are you so rude? You don’t even know me.” After that, he followed me around and came to my house to ask for my hand in marriage. At that time, my late father was still alive so he advised me to think it over between a bachelor and a widower. He said it was better to live with a bachelor. Since I didn’t love either of them, I just followed my father’s advice and got married to my current husband. But it was only ten short years of happiness. After my first abortion, ten years later, things got rough.

The way I see it, if your parents are alive you dare not refuse their advice or complain. If you follow your parent’s advice you will blame them for your unhappiness. However, that is not the case for me. All I can do is be regretful and accept this decision as a sin from a previous life. If my father were alive, I would blame him as well for his misjudgment. I just feel sorry for myself. My life is an endless sad story. I don’t want to talk about it anymore.

This interview has been edited. It was conducted in two parts. The first took place on August 4, 2014. at the shoe factory where Channa was worked. The second time we met was on August 9, 2014, at the apartment complex where she lives on the outskirts of Phnom Penh, Cambodia. She quit her job at the shoe factory. You can read the original interview here

Primary Voice is a collection of primary source interviews dedicated to documenting the living stories of garment factory workers worldwide. It was created by urbanist Mikaela Kvan. To read more interviews and to get in touch visit www.primaryvoice.org.

22-year-old Huang has been working in garment factories for about five years. Photo by Daniel Huang

I have been working in garment factories for four or five years. I am 22 years old now. When I graduated from junior high school I had nothing to do. Someone told me how good making clothes was and they introduced me to the industry. At that time I thought I was young so it would be good to learn something new. I started to make clothes then and I still do now.

I had many dreams when I was little, such as being a doctor or a policewoman or even being rich. I was so naïve then. Take the doctor dream for example. I am so scared of seeing blood. I once saw someone’s injury from a car accident. OMG, it was terrible. I couldn’t even look at the wound, let alone touch it. I even saw a dead body once. How can I be a doctor if I am so afraid of blood, injuries and death?

My plan is to work at the garment factory for a few more years but I won’t do it for the rest of my life. I will go back to my hometown to open a store in a few years. I just want to open a store, but I don’t know what kind yet.

When I graduated from junior high school, my mom asked me to keep studying but I didn’t. I was in a dilemma. My mom didn’t want me to work in the city at such a young age. She wanted me to stay in school but I was rebellious. I didn’t do well in school so I thought, “Why bother studying and spending money on my education?” I just came to the city to work so I could support myself. It was a very difficult decision for me. My mom tried to force me to study but I wouldn’t go. Honestly, I regret the decision a bit. I should have gone back to school.

For girls, it is better to learn something not so tough. I think I would learn to make patterns for clothes or something using electronic devices if I could go back to school. I want to learn something easy because I am a lazy person. I like doing finishing work for others so I don’t have to make everything from the beginning.

In terms of social life, garment factory workers like us don’t have time to take a break because we need to do overtime to keep up with production. I go out on public holidays, but there are so many people and cars during that time. I remember I went to a museum park once and I waited in line to get in from 7am to 10 am at the entrance. There were so many people there. For me, having a social life means going out shopping. Girls like shopping and buying cosmetic products. We should spoil ourselves from time to time.

For example, I once spent 2000 RMB (330 USD) to buy a set of Mary Kay products. It is a big brand that I can trust. I buy skin care products instead of make-up. It is important for me to take good care of my skin to look young and pretty because there is dirt and dust around the factory. When I first came to the city, my skin was dark but my skin is getting better with good care. I think it is better to take care of my skin as I grow older. Dirt around the factory may clog the pores in my skin and cause various skin problems. To help, I give myself facials.

Concerning other self-care, I rarely exercise. Firstly, I don’t have much time and secondly, I am too lazy. I will sleep late whenever I have a day off. I am so lazy that I miss the time to exercise. I also hate to wash my clothes because I am lazy. I think it’s best if there is a washing machine but there is no machine so I just wash the clothes myself. When I finish my shower at night, how I wish someone would wash my clothes and I could just lie in bed and play with my phone. But no one is there to help me. Even if I forget about them for half a month, I still have to wash them myself.

This interview has been edited. It was conducted on July 13, 2014 at the factory where Huang works in the industrial area of Yantian east of Shenzhen, China. You can read the original interview here

Primary Voice is a collection of primary source interviews dedicated to documenting the living stories of garment factory workers worldwide. It was created by urbanist Mikaela Kvan. To read more interviews and to get in touch visit www.primaryvoice.org

Yesterday I fulfilled a long-held dream and visited Guna Yala on the San Blas islands, off the Caribbean coast of Panama. The purpose of my trip was to meet the skilled women who create molas.

The Guna were driven from their original home in Colombia In the 16th century by Spanish colonists, north through the Darien rainforest region to the coast of Panama. From there, they migrated to the semi-autonomous region where they live today called Guna Yala, an archipelago of coral islands in the Caribbean off the coast of Panama.

16th century manuscripts describe Guna women paying careful attention to their appearance with elaborate body painting, skirts of pounded bark, necklaces and a nose ring. In the mid-18th century, European settlers introduced cloth to the islands and the started to paint it in the same way they had painted their bodies: black from jagua juice, red from annatto juice, and yellow from turmeric root.

The term mola originally meant bird plumage. It later became the Guna word for clothing and is now used solely for the double panel, front and back, on their blouses. Some of the Guna’s first games will involve pretending to make molas and they will later create their first blouse to wear during the puberty ceremony. At death, they will be buried with their molas.

The technique used to make molas is known as reverse appliqué. A Guna woman will put several pieces of cloth, often recycled, on top of each other and tack them together. She may have draw her design first, but often she just follows her imagination as she starts to cut a design into the top layers. Only the bottom layer remains intact and becomes the background. The colour of each layer is revealed as she cuts out her design. Once the reverse appliqué design is complete and the edges finely hemmed in matching thread, she will often add positive appliqué and embroidery to complete her mola.

Initially, mola designs were geometric patterns which reflected their body painting and jewellery. Inspiration from their surroundings was later introduced: flowers, birds, fish and sea creatures are common motifs.

On the island of Icodub, I met Crichel, a shy 16 year old. There are few opportunities on the islands, other than fishing and tourism. Although there is a primary school, Crichel had to move to Panama City for her secondary education. Her mother, Migdalia Chiari, moved to Panama City when she was younger to train as a designer, but ran out of money to complete her studies . Crichel’s dream is to follow in her mother’s footsteps and train as a designer, bringing the mola designs of her culture to the catwalk.

I am particularly interested in transitional art, the result of acculturation creeping in to traditional designs. I resisted the Dora the Explorer mola, mainly because it only used positive appliqué which is becoming increasing popular as it requires less skill and time, but purchased one based on a Swedish box of Parrot matches which had been left by a visiting tourist. Despite outside influences from the media and tourism, the Guna have managed to retain a balance between between infiltration from the modern and their traditional way of life.

However, there is another threat to the Guna cultural traditions: climate change. As sea levels rise, these islands are experiencing regular flooding and will eventually become submerged and the 30,000 people who live in Guna Yala will have to move to the mainland. Whether Guna cultural traditions, including the making of molas, will survive this relocation remains to be seen.

Matt is a 28-year-old garment worker in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Photo by Sok Chanrado

I’ve been working in garment factories since 2004. It’s been ten years. During those years, a lot in my life has changed. I used to live with my aunt before I started working so I would do all of the chores around her house. Now that I earn my own income I can afford to buy whatever I want and I can help my younger siblings go to school. I have two sisters and one brother. I am 28, my brother is 26, the third is 24, and the last one is 19 years old. My two younger sisters also work in garment factories but our brother goes to university.

I had a rough childhood so I want to forget about it. When I was young I sold things in the market like fish and meat. I sold anything I could. I would sell things for other people, too, in order to save for my siblings and me to go to school. We lived in Sihanoukville then and my family was poor. All of my siblings had to work to earn money for school at the age of seven or eight. In 2004, my mom passed away. That’s when I quit school.

My father was a drunk. He always caused problems – swore at us or threw things around the house or kicked us out. Because of his abuse I decided to bring my siblings to Phnom Penh to live with our aunt. After living with her for about 4 months we had to rent our own house. The financial burden was too much for her.

When I was a child I dreamt that I would finish school and get a good job that could support my family and me. When my mother died I had to quit school to work because I am the oldest sibling. I was only in fifth grade. I felt such pity for myself after quitting school. Ultimately, I had no choice. Time wouldn’t stop. I had to look forward and take care of my siblings.

I must sacrifice myself for their sake. It hasn’t been easy. At times I feel really irritated and stressed but when my siblings behave themselves, and don’t give me a hard time, I feel my capabilities are limitless. Even if we don’t have parents, we still have each other. As the eldest sibling I feel a great responsibility to be a good role model for my brother and sisters.

Financially, we can only depend on ourselves. Unlike others whose parents are still alive, we can’t survive without working. I don’t have the luxury of living that way. If it were up to me I would not work in a garment factory. I want to open a small shop where I have the potential to earn income daily. With my current job, I have to wait until the end of the month to get a paycheck from the factory. By that time, I need to pay rent and it seems I have nothing left. Unfortunately, I don’t have the ability to realize this dream for myself right now because I need to support my brother who is in university. Once he graduates I could probably quit my job at the garment factory and open my own shop. I’m optimistic about my future. When my siblings were young, I worried they wouldn’t listen to me. But it turns out my siblings are good kids. I hope the future will be easier. Since I am having a hard time for their sake now, I believe they will think about me when they have jobs.

This interview has been edited. It was conducted on August 10, 2014, outside Matt’s room in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. You can read the original interview here

Primary Voice is a collection of primary source interviews dedicated to documenting the living stories of garment factory workers worldwide. It was created by urbanist Mikaela Kvan. To read more interviews and to get in touch visit www.primaryvoice.org

Brands are like global ambassadors that immortalise cultural periods, bridging customers together across time zones and generations. It is hard to think about France without thinking of their most notable fashion brands like Louis Vuitton or Cartier, but that is not the case for African nations. Outside of breathtaking tourist attractions and natural resources, the continent is unrepresented among major brands. In addition, creativity is rarely held in high esteem across the continent, leading to a devaluation of African innovation.

Luckily, contemporary African creatives across the diaspora are approaching this dilemma with a fresh set of ideas. Introducing A A K S, the emerging Ghanaian accessory brand that is taking African craftsmanship to new territories. Founded by Akosua Afriyie-Kumi, A A K S took raffia, a natural fibre, with great ethical values from obscurity and repurposed it into luxury patterns and hues.

Handcrafted is the A A K S brand philosophy and production is rooted in traditional weaving techniques passed down from generations of iteration. The body of each bag is hand-woven by weavers from the Northern Region of Ghana in a small tranquil town called Bolgatanga. The woven body is then transported to the main A A K S studio in Kumasi, where the linen and cotton linings are sewn, buckles are hand stitched, and leather straps are secured to complete the bags. Following a final quality check, the bags are then shipped to 27 worldwide partner stores, including Anthropologie and Urban Outfitters.

Creating a handcrafted product has always been the goal of the brand. Founder Akosua shared that, “we strive to be a transparent sustainable brand that designs small capsule collections, allowing us to focus on quality and authenticity. In the long run we hope that our brand will drive the revival and sustenance of weaving as a thriving art.” An inherent part of their business is to support the surrounding craftsmen and farmers, using locally sourced raffia and organically made dyes. On a continent where environmental health is lagging, sustainability is at the core of A A K S.

Weaving affords the women and men steady incomes, empowering them to become independent as they create a refined luxury good. Each artisanal weaver brings lasting originality to A A K S and we know customers will sense the dignity and ownership put into each bag.

Six years after a major earthquake devastated the Haitian capital and its environs and the international community promised to “build back better,” Haitian workers say their daily lives are a struggle for survival, with their meagre wages insufficient to cover basic expenses.

In recent interviews, Haitian garment workers told the Solidarity Center that they are worse off today than before the quake. With prices rising and wages largely stagnant, their paychecks do not allow them to support themselves and their families.

“We spend almost our entire daily wage on food and transportation,” said one garment worker interviewed. “We cannot save any money and we do not have enough money to get health care or education. Our future is compromised.”

Another worker said he sometimes has to borrow money to “make sure that at least the family has something to eat.”

Haiti is the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere and one of the poorest in the world. According to the World Bank, more than 6 million of Haiti’s 10.4 million people (59 percent) live under the poverty line.

Haitian garment workers hold rare full-time jobs in an economy that is largely informal, and work for profitable multinational manufacturers, some incentivized to come to Haiti and create jobs after the quake. Yet garment-sector wages are legally set below the national minimum wage and well below what is necessary to cover basic costs. A December 2015 Solidarity Center analysis of living expenses found that the average garment worker spends 160–225 Haitian gourdes ($2.80 – $3.94) a day on food and transportation for herself, and another 395 gourdes ($6.91) on food for the household. The current minimum daily wage for garment workers, who work 48 hours a week, is 225–240 gourdes ($3.94–$4.20). The minimum wage is supposed to increase this spring, to $5.11 for an eight-hour shift.

In 2013, Haitian workers and their unions waged rallies and protests to demand that the daily minimum wage be increased to 500 gourdes ($8.75) for export apparel workers. The government set the wage at less than half of that. In 2014, the Solidarity Center found that a living wage of 1,000 gourdes per day would allow workers to meet their basic needs.

“As we mark this grim anniversary, we have to ask why the people best-positioned to revive the Haitian economy—hardworking Haitians—are handicapped by abysmal and degrading wages. Until Haitians can earn a living that allows them to do more than barely survive, there will be no real recovery,” said Shawna Bader-Blau, executive director of the Solidarity Center. “The international community and Haitian government should be ashamed of policies that guarantee poverty wages and grant concessions to multinational corporations instead of providing real opportunities for Haitians workers to improve their lives and livelihoods and build a better country for themselves and their children.”

JOIN THE FASHION REVOLUTION

The Fashion Revolution is a movement to create a visionary fashion industry that values people, the environment, creativity and profit in equal measure. The idea is that by being curious and finding out about textile suppliers, consumers can inspire change and promote transparent supply chains that match that vision.

I know who makes all of our Tallis products, by their first names. Tallis is about considered craftsmanship, as we sell hand-made, artisanal accessories that have been created from carefully selected materials from trusted sources. The Fashion Revolution movement evidently strikes a cord with me. I agree that products should be made in an ethical way which ensures the wellbeing of workers in the supply chain and raw material production as well as the protection of the environment. Knowing who makes our products is the most straight forward way I can ensure that.

For some companies, it is hard to keep a grip on protecting worker wellbeing when your main business is turning out lots of cheap clothes very quickly.* This is because knowing who made what at that kind of scale requires a different kind of monitoring, and it’s harder to know the source of raw materials which change every week. It is much easier to control your supply chain when your business model is to create products designed to last, as the intrinsic value in this approach is that it gives you the freedom to take more time. More time to make the products and more time to check where the materials have come from. You can be more transparent and reap the rewards of the value that adds to the product. It’s the slow fashion idea.

It is in our DNA to make products that last, out of materials that would stand up to being repurposed, such as fur which lasts and lasts. We also believe in actively avoiding waste, by making our hats from vintage cashmere or using pre-consumer waste (factory offcuts). It’s harder to do than buying virgin materials and it requires creativity, but it gets around many issues in raw materials sourcing.

Our pieces are investment pieces because they are made from high quality materials and hand-made by artisans. The majority of our designs are also multifunctional with an idea to being multi-seasonal or multi-use. You don’t buy a Tallis every week but when you invest in one, you know it’s a product you will wear over and over again.

These principals run through the story of each of our products. We have hats hand-made by Faith out of vintage cashmere jumpers. Shearling scarves hand-cut in a workshop in Geneva by the women at Label Bobine. Capes I sit down to make at the fur machine. Pompoms hand-sewn by Carmen in the workshop in Lausanne or, if theres a special customer, I do it in front of the TV with a cup of tea.

I could make all our products cheaper, by buying cheaper fur from a supplier I don’t know or in a region where I’d have to turn a blind eye to known production issues such as poor animal welfare or environmental stressors. I could also outsource all our production to factories I haven’t visited because they are cheaper. But that’s not the product I’m trying to make or the commitment Tallis inspires.

“Knowledge, information, honesty. These three things have the power to transform the industry. And it starts with one simple question: Who made my clothes?” – Fashion Revolution.

I made your clothes.

– Lilly Milligan Gilbert, Tallis Founder – Geneva 2 December 2015

Inés is from Mexico and she lived there until one day her uncle —who lived in LA with her aunt at the time— got into a horrible car accident. He was the sole source of income and Inés’ aunt was left with no other option than urge someone from her family come urgently and help. So Inés did. She uprooted everything she knew and left her family and friends. She risked her life to travel to a country she did not know to live on the margins of society and work very hard for little pay, just to help her family survive through a bad patch.

But this is not a story about Inés. This is about thousands of women refugees and immigrants just like her coming to the United States because they have been driven to abandon their home countries in search of a better future. The details change but the themes remain the same. They also have all experienced tremendous hardship. They have all abandoned their homes, families, and the people they love to come here. They have not had the luxury of gaining a good education – most of them do not even have a high school degree or even a GED. They live in such frugal conditions that planning for the future is impossible. And yet, you’d be hard pressed to meet more hopeful women and mothers.

I have heard the stories of their plights repeatedly. These women are at an impasse because without a basic education such as a GED, it’s difficult to get work.

This is why we created Vavavida, to find real solutions to the problems underprivileged women face. Inés is the reason that we exist. But last year, we weren’t helping women like Inés. You see, Vavavida is an ethical fashion e-tailer of beautiful jewelry and accessories that was focused on empowering women’s economic future abroad. We retailed products made by co-ops of artisans in developing countries following the fair trade principles.

Fair trade is quickly becoming the quality standard with commodities like chocolate, coffee, tea and bananas, but it often overlooks workers in first world countries like the United States.

In 2015, we resolved to bring fair trade opportunities to underprivileged women and refugees like Inés here in our home base of San Diego, California. Vavavida partnered with Jennifer Housman, a jewelry designer and a volunteer with PCI to create an artisan co-op of refugees here in the United States. This co-op will give them an opportunity to work from home in conditions where they can work as little or as much as they can any given day and be rewarded with a fair pay for their work. This way, they are empowered to take charge of their own future and do not have to give up money or family time by putting their kids in daycare.

We teach women like Inés to design and make jewelry inspired by the artistic traditions and designs of the regions where they come from. This was our 2015 resolution and we are proud to see the pilot program become a reality. In 2016 we resolve to continue to invest in these women and this program.

What do you resolve for 2016? Please share in the comments section below.

Antoine Didienne is the co-founder of Vavavida, a line of ethically made fashion jewelry items that give back.

“You have forgotten the Tazreen fire incident but our actual suffering has just started,”

says Anju, who experienced severe head, eye and other bodily injuries during the fatal Tazreen Fashions Ltd. fire in Bangladesh in November 2012 that killed 112 garment workers.

Survivors of the Tazreen fire who recently talked with Solidarity Center staff in Bangladesh say they endure daily physical and emotional pain and in many cases, have little or no means of financial support because they cannot work. Some, like Anju, who is unable to work, have never received compensation for their injuries.

Bangladesh’s $25 billion garment industry fuels the country’s economy, with ready-made garments accounting for nearly four-fifths of exports. Yet many of the country’s 4 million garment workers, most of whom are women, still work in dangerous, often deadly conditions. Since the Tazreen fire, some 34 garment workers have died and 985 have been injured in 91 fire incidents, according to data collected by Solidarity Center staff in Dhaka, the capital.

Some 80 percent of export-oriented ready made garment (RMG) factories in Bangladesh need improvement in fire and electrical safety standards, despite a government finding most were safe, according to a recent International Labor Organization (ILO) report.

The Solidarity Center has had an on-the-ground presence in Bangladesh for more than a decade. Through Solidarity Center fire safety trainings for union leaders and workers, garment workers learn to identify and correct problems at their worksites. But fewer than 3 percent of the 5,000 garment factories in Bangladesh have a union. ” Despite workers’ efforts to form unions, in 2015 alone the Bangladeshi government has rejected more than 50 registration applications—many for unfair or arbitrary reasons—while only 61 have been successful. The rejections have jumped significantly from 2014, when 273 unions applied and 66 were rejected.

So that the world does not forget, here is the story of Anju and others who survived the Tazreen fire.

Anju, 45, suffers from neurological and other complications resulting from the injuries suffered during her escape from the Tazreen fire. She says the income her husband earns pulling a rickshaw cannot support their four children and pay for her medicine.

“The treatment cost is high and we cannot bear it,” she says. “Everyday life is difficult.”

Shahnaj Begum, 48, and her daughter Tahera Begum, 30, both survived the Tazreen factory fire. Shahnaj was severely injured, including the loss of her right eye. Shahnaj received some compensation, but it was not enough to pay medical bills and ongoing support.

“Many lives could have been saved if the factory was not locked. The biggest tragedy for us is the culprits have not been punished.”

Jorina Begum, 25, cannot afford medical treatment for the injuries to her spine and body she sustained at Tazreen, and her physical condition is worsening. Jorina’s sister, also injured when the factory burned, died recently. Now there is no one left to support the family. She says two things will give her peace of mind:

“I want compensation so that I can manage the support of my family members and I want to see that the person who is responsible for it is punished.”