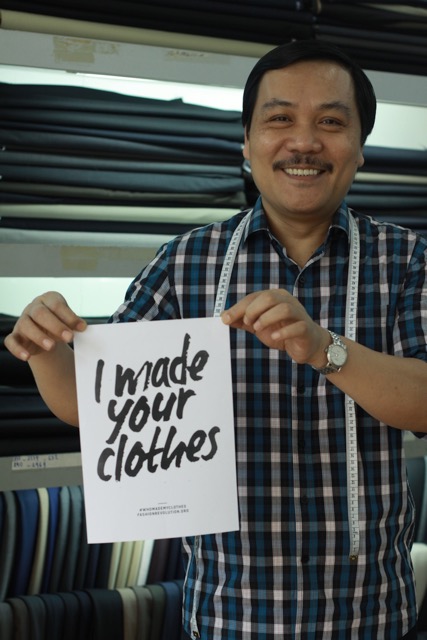

Their story began with a splendid white dress shirt made by a smiling tailor in an alley of HoChiMinh City, Vietnam. Beyond the singular experience of wearing bespoke garment for the first time, it is the direct purchase from its maker that was the trigger. “Each of us now wants products that answer one’s individual needs”, says Bernard, “I hate shopping malls and I love buying unique items. I am fascinated by nice objects and the stories behind them. That’s how the idea to create an ecommerce marketplace for custom made clothes and accessories handmade in South East Asia came out.”

For the Belgo-French duo, Bernard Seys and LouAdrien Fabre., connecting consumers directly with makers creates better outcomes for everyone. As the sole vendors on efaisto.com, makers are in full control of their pricing. They receive up to 85% of what the customer pays, net of all fees.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=edHJvRvx71o&feature=youtu.be

As each item is made on demand, the makers do not have large production batches, minimum order quantities nor canevas to follow. By essence, each bespoke product has to be cut, sewn, dyed, engraved, polished or coated individually by human hands. Which results in a drastic reduction of waste or unsold products and an increased average lifetime of the product.

The buyers have the opportunity to get tailored clothes and custommade accessories at a fair prices, and know who made them.

We are the first factory brand to be making authentic premium quality jeans in London for at least the last fifty years. Perhaps the first ever to be making selvedge denim garments in London.

As a community focused enterprise, all factory employees and machinists are shareholders in the company. A place to observe and learn how jeans are created and to visit our allotment growing Japanese indigo to dye the garments.

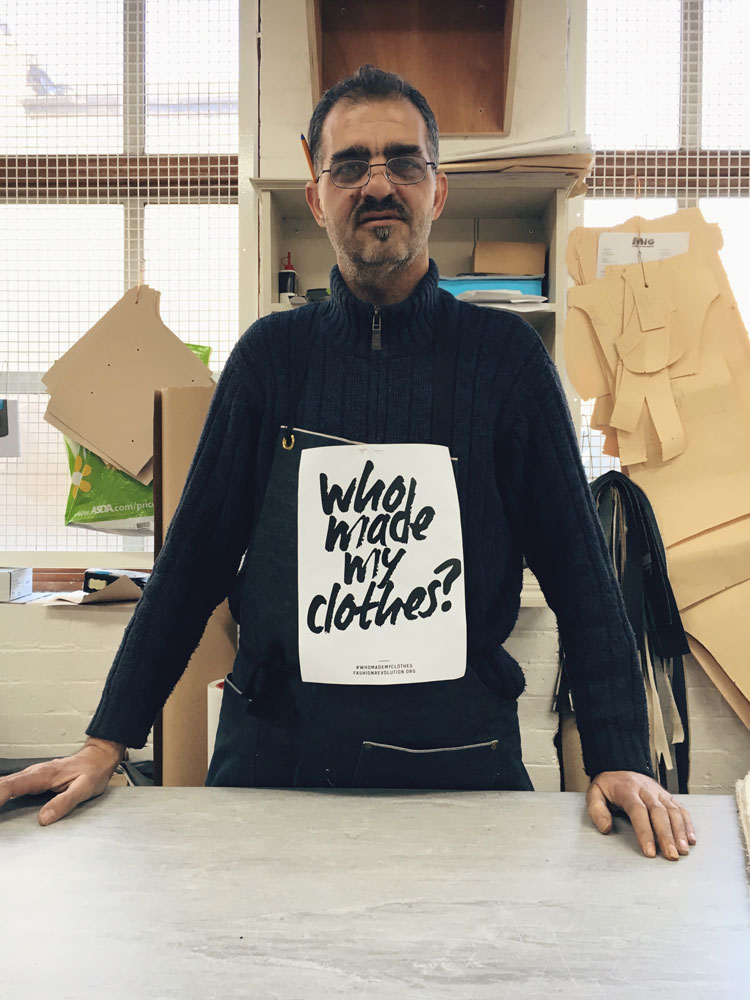

Name : Mr Husseyin

How long have you been in manufacturing? 40 years

How did you get into manufacturing ? Both my father and grandfather were tailors in Turkey for their whole lives and it influence me to do the same.

How does working here compare to other jobs in manufacturing? It is better than anywhere I have worked before.

What does working here mean to you? I have more opportunities and better life prospects.

Name : Ms Emine

How long have you been in manufacturing? 10 years

How did you get into manufacturing ? I learned to sew In Bulgaria and have been sewing for 10 years now. I’ve lived in London for 4 or 5 years and I am very happy to use the skills I have here.

How does working here compare to other jobs in manufacturing? It is better than any other factory I have worked in. The space is much cleaner and bigger and a much nicer place to work.

What does working here mean to you? It means I can carry on using my skills to earn a good living to make a better life for myself.

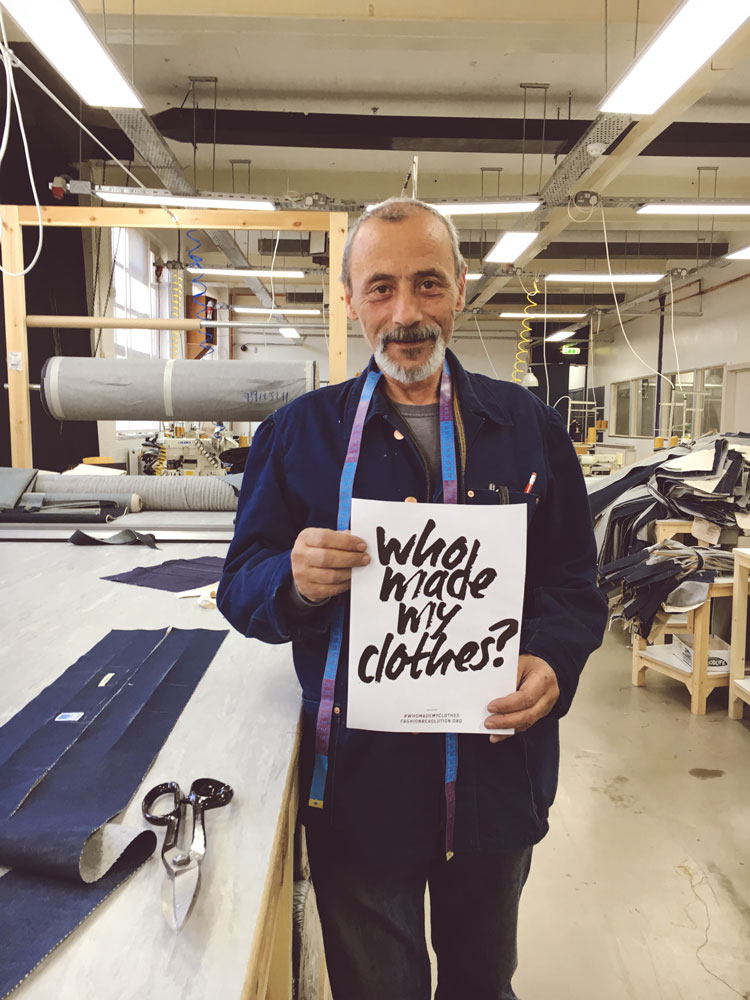

Name : Mr Kenan Habali

How long have you been in manufacturing? 40 years +

How did you get into manufacturing? It is the only thing I know and the thing I know best.

How does working here compare to other jobs in manufacturing? It is better than anywhere I have worked before.

What does working here mean to you? Bread Money

Name : Mr Iliev

How long have you been in manufacturing? 22 years

How did you get into manufacturing? I enjoy the job, I used to work in manufacturing in Bulgaria where I am from.

How does working here compare to other jobs in manufacturing? The conditions are much better and we are treated equally.

What does working here mean to you? It means I can come to work everyday and work hard to earn a good living

Name : Mr Dimitar Conev

How long have you been in manufacturing? 27 years

How did you get into manufacturing? I like the job, sewing and manufacturing is something I enjoy doing.

How does working here compare to other jobs in manufacturing? We are paid a lot better and the working space and conditions are a lot better.

What does working here mean to you? It means I can earn a living and afford a better standard of life.

Name : Ali

How long have you been in manufacturing? 30 years

How did you get into manufacturing ? It is my favourite job. I enjoy sewing and manufacturing more than any other job.

How does working here compare to other jobs in manufacturing ? This is the nicest factory I have worked in.

What does working here mean to you? It means I can earn a proper living.

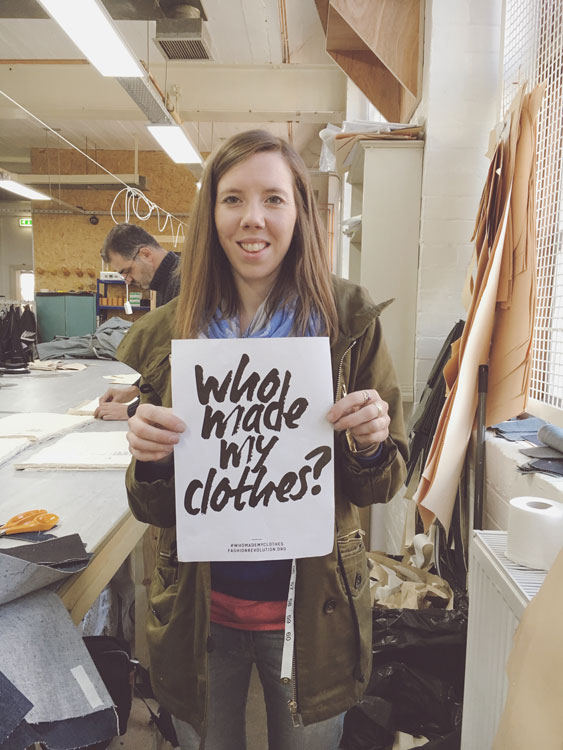

Name : Megan Fisher

How long have you been in manufacturing for ? I have been sewing for 15 years, since I was a little girl.

How did you get into manufacturing ? My mum was always really good at sewing which really inspired me, and I enjoyed textiles classes as school, the passion just grew from there.

How does working here compare to other jobs in manufacturing ? It’s really different because everyone is really honest and open. its a very transparent company, which means we have lots of visitors to see what we do.

What does working here mean to you ? It mean that i get to live an exciting life of living and working in London.

The antithesis of fast fashion, denim jeans are known universally as the quintessential egalitarian garment, with a slow heritage dating back 150 years. Launching in April 2016, the Blackhorse Lane Ateliers is an entirely unique factory brand and manufacturer of superior quality denim goods. Based within a tastefully renovated 1920s factory building in Walthamstow, the brand combines the production of artisan jeans with the establishment of a modern methodology for community living – Think Global, Act Local.

The key element of the Blackhorse Lane Ateliers manifesto has been to challenge the commonly held, modern day attitude of short-term gains, instant gratification and disposability, by implementing a more sustainable, ethical and transparent business model, to the advantage of the consumer. In order to keep the carbon footprint low, each pair of jeans will be produced within their London Atelier and crafted by local Londoners, using only the finest quality selvedge and organic denim, expertly sourced from Europe and Japan.

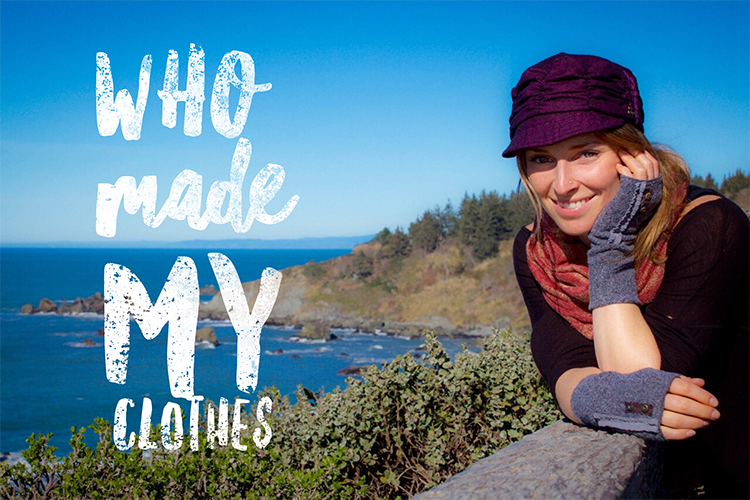

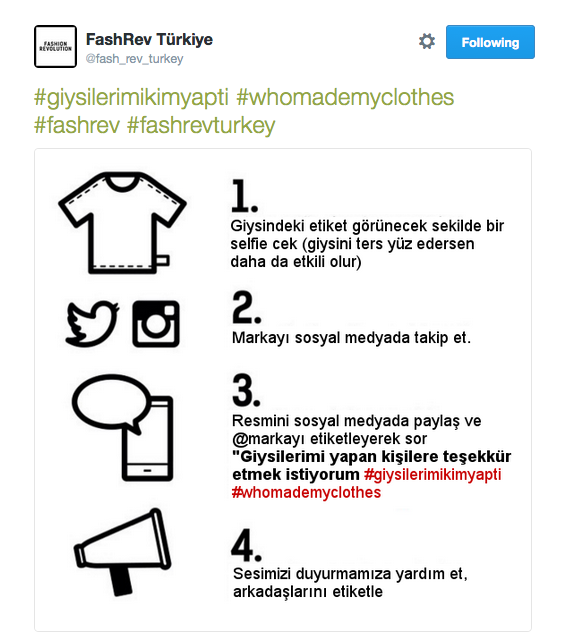

This year, Fashion Revolution Week took place in 89 countries around the world. One of these countries was Turkey.

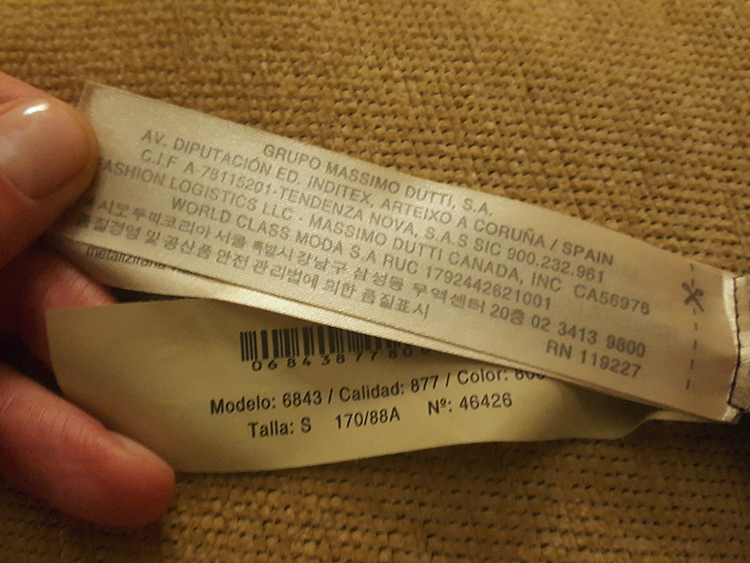

Deniz Ucok saw this post and decided to ask Massimo Dutti who made her T-Shirt #whomademyclothes?

Massimo Dutti is a Spanish clothes manufacturing company, founded in 1985, which is part of the Inditex group. Massimo Dutti is not a real person, but a trademark. Despite the Italian name, it is a Spanish company employing over 4000 people worldwide.

Massimo Dutti responded by asking Deniz to send them a photograph of the labels in her T-Shirt.

And Massimo Dutti certainly can answer the question #whomademyclothes, as shown by their comprehensive answer below.

Dear customer,

The item you requested information about was purchased from a Portuguese Company for the Summer collection 2016. The name of our supplier is Vieira & Marques, Lda. and their facilities are located at San Martinho Campo. It has 180 employees and it received the highest score during our latest social audit which will be revised again throughout this year (2016.)

During the manufacturing process other Portuguese companies have intervened:

For fabric manufacturing: Vilartex Emp de Malahas V Lda based in Guimaraes and with 106 employees.

For tinting processes: Carvitin Tintura e Acabamentos Lda, based in Coimbra with 56 employees.

For confection: M Look Confeccoes based in Fomelos with 40 employees.

For ironing: Jose Amorim Mota Unipessoal Lda, based in Guimaraes with 67 employees.

All these factories have been examined by our social audits as well as production audits that assure the clothing traceability.

We hope you find this information useful.

Kind regards,

Massimo Dutti

Deniz replied to Massimo Dutti on Twitter.

Inditex scored 76% overall in Fashion Revolution’s Fashion Transparency Index, published on 18 April, just one percentage point behind the leader, Levi Strauss & Co. To find out more about the scoring and methodology of the index, please read our Top 10 FAQs

Today marks the anniversary of the tragic Rana Plaza garment factory collapse in 2013. Since that day Fashion Revolution has been encouraging people to demand change from the industry so that accidents and exploitation become uncommon if not extinct.

There is no easy solution. There is not just one enemy, as there is not just one hero.

The fashion industry affects us all. It affects the people who work in it and the people who enjoy the fruits of that work. It has a huge impact both on our global environment and our personal space, from our high street to our individual wardrobe.

Fashion inspires very strong feelings – from disdain, anger, frustration to wonder, empowerment and love. We see Fashion Revolution as a safe place to discover the contradictions that affect this industry to its core. We see ourselves as a springboard and community for citizens to embark on an individual yet collective journey towards positive change. It is complicated, emotional and deeply important.

Fashion Revolution was always conceived, by its founding team, to be a platform for saying it as it is. We encourage and praise positive steps towards greater transparency, but also scrutinise and highlight where improvements need to be made.

Transparency is only the beginning – a tough, complex start

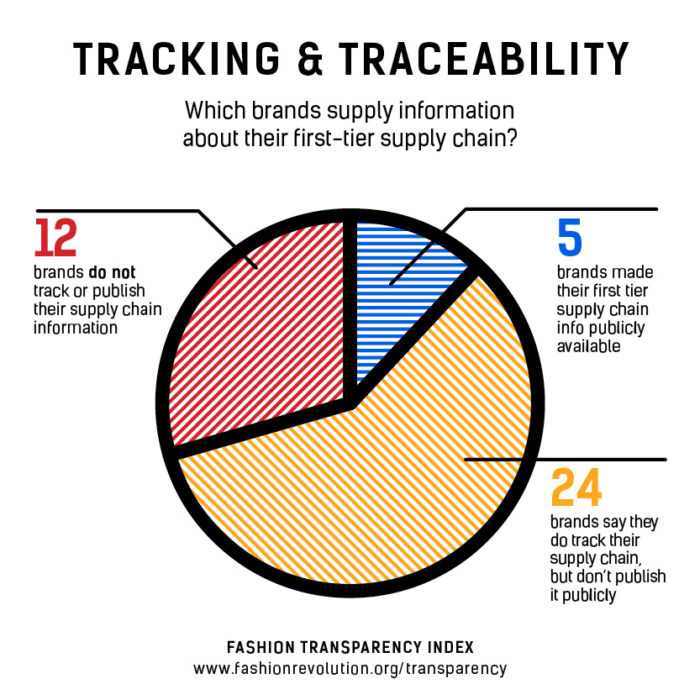

The Fashion Transparency Index was a big learning curve for us, not just because it showed us how few brands are actually willing to share information about their supply chains publicly (out of 40 brands we asked, only 10 initially replied) but because it reiterated the fact that the fashion terrain remains muddy and slippery, and the road to real change is uphill.

Our research looked at a tiny sliver of the fashion industry’s huge problems. We only investigated how transparency in supply chains is being publicly communicated. It showed us some good stuff, some bad stuff, and a lot of unknowns. This kind of research is tough, the scale of the industry is immense.

We worked with Ethical Consumer in the UK who has been benchmarking the practices of companies for 25 years. We are pleased to see that The Truth Behind The Barcode 2016 report and Oxfam Australia’s new research Still in the Dark, both looking at supply chain transparency in the Australian market, employed similar methodology and mirrors many of our findings.

What it showed us is that a few behemoths talk a lot about some of their supply chain issues, but most of the industry seems to be doing very little to ensure that people and the environment are protected throughout the value chain – or at least not sharing this information with their customers, which is really important.

In terms of trust in what brands tell us, we are a long way from knowing who we can rely on. But in terms of awareness, we have come a long way in ensuring that there is a demand for brands we can genuinely trust.

We are only at the beginning of this journey. There is much to learn. We will continue to ask brands #whomademyclothes. We will continue to let people know how much or how little information is publicly available. We will develop the Fashion Transparency Index to include more brands, ask more questions, work with more partners, refine the methodology, and strengthen our quest for more disclosure of the people and processes behind what we wear. Ultimately, when brands publish information about their supply chain activities, NGOs, the media and civil society can better hold them to account for the good and bad.

We must also remember that the fashion industry provides millions of people with employment, particularly women in the developing world, and our attention should focus on amplifying the need for jobs that are providing a decent living wage, dignity of toil to the producers and assurance that their workspace and their environment is safe, secure and adequately regulated.

It’s more than just a week

We have been celebrating Fashion Revolution for a whole week this year, and we have been surprised and delighted at the actions and conversations over the past six days.

Films were made, dances choreographed, fashion shoots hacked, flags made, stunts experienced, public wardrobes opened. Our voices and stories were featured in the global press like never before: showing the world that fashion matters and that turning this industry into a force for good is a real priority.

Over the week we have been joined by celebrities and influencers like pro surfer Kelly Slater and his brand Outerknown, supermodel Amber Valletta, actress and activist Rosario Dawson, actor Jesuita Barbos, actress Bonnie Mbuli, style icon and fashion editor Caroline Issa, TV presenter and cook Melissa Hemsley, Italian Youtube vlogger Greta Menchi, journalists Elisabeth Cline and Marion Hume, and Queen of the Green Carpet Challenge Livia Firth, to name a few.

We have been incredibly inspired by how young people are talking about the issues. From hugely famous YouTubers to novice vloggers from all walks of life, the #haulternative project has proved to be as engaging this year as it was last year, a true global phenomenon.

CutiePieMarzia’s contribution already has over 250,000 views in two days with one of her fans commenting

“thanks to you for inspiring me and educating me on where my clothes actually come from.”

And people have shared some fantastic Love Stories about their clothing with the world, a reminder that what we already have in our wardrobes deserves our attention and respect.

This year university students from all countries have signed up to become Fashion Revolution Student Ambassadors and using our engaging education resource platform has instigated creative and thought provoking events and actions around the world.

We have also seen a number of fashion brands getting involved and some attempting to answer the public’s #whomademyclothes requests: such as Marimekko, GStar Raw, Winter Water Factory, Warehouse, ARMEDANGELS, Levi Strauss, Honest by, People Tree, Veja, Ginger & Smart, Boden, Irregular Choice as well as many others.

There has been some provocative and educational global media coverage about the need for greater transparency in the fashion industry, including the Sydney Herald Tribune, Estadão, Dazed magazine, i-D, Refinery29, Vice News, Grazia Spain, The Pool, The Telegraph, Bustle, The Independent, Vogue Italia and others.

Our scale is our strength

Fashion Revolution is truly a global movement that relies on the dedicated efforts of our Country Coordinators. All 89 of them have worked tirelessly and brilliantly to engage their constituencies in original, effective and powerful ways. We talk a lot about the true heroes and the invisible workforce behind the clothes we wear. Well, our Country Coordinators too are the true heroes, the force that runs Fashion Revolution.

Together, we will keep on working to make small, large and important steps towards an industry that values people, planet, profit and creativity in equal measure.

I was working with the Fashion Revolution team yesterday at London College of Fashion. I needed a swimsuit for my upcoming Zoology research trip to the Bahamas and heard that AURIA swimsuits were for sale at the EMG Progressive Fashion Concept Store in Beak Street, Soho, just a few blocks away. I found the perfect swimsuit! As it’s Fashion Revolution Week, I of course had to ask the question #whomademyclothes?

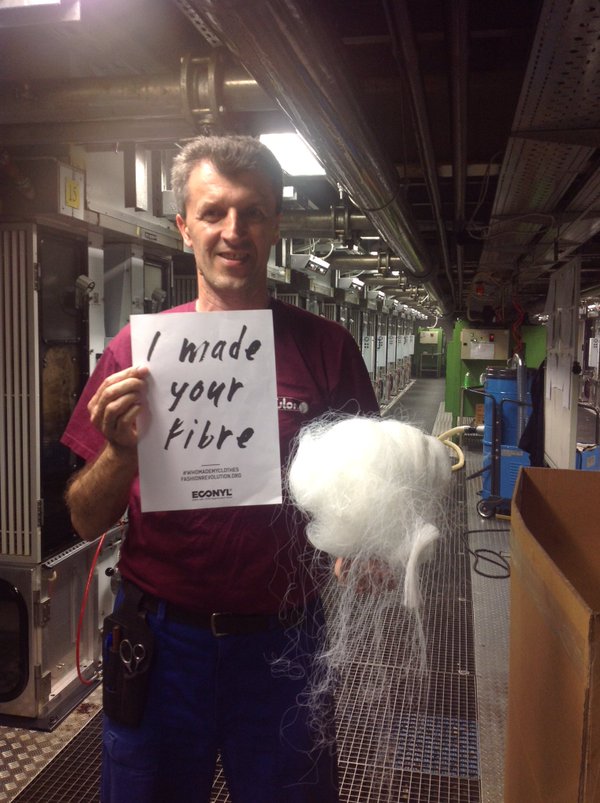

AURIA’s swimsuits are made from Econyl.

According to their website ‘the innovative ECONYL® Regeneration System is based on sustainable chemistry. With this process, the nylon contained in waste, such as carpets, clothing and fishing nets, is transformed back into raw material without any loss of quality.

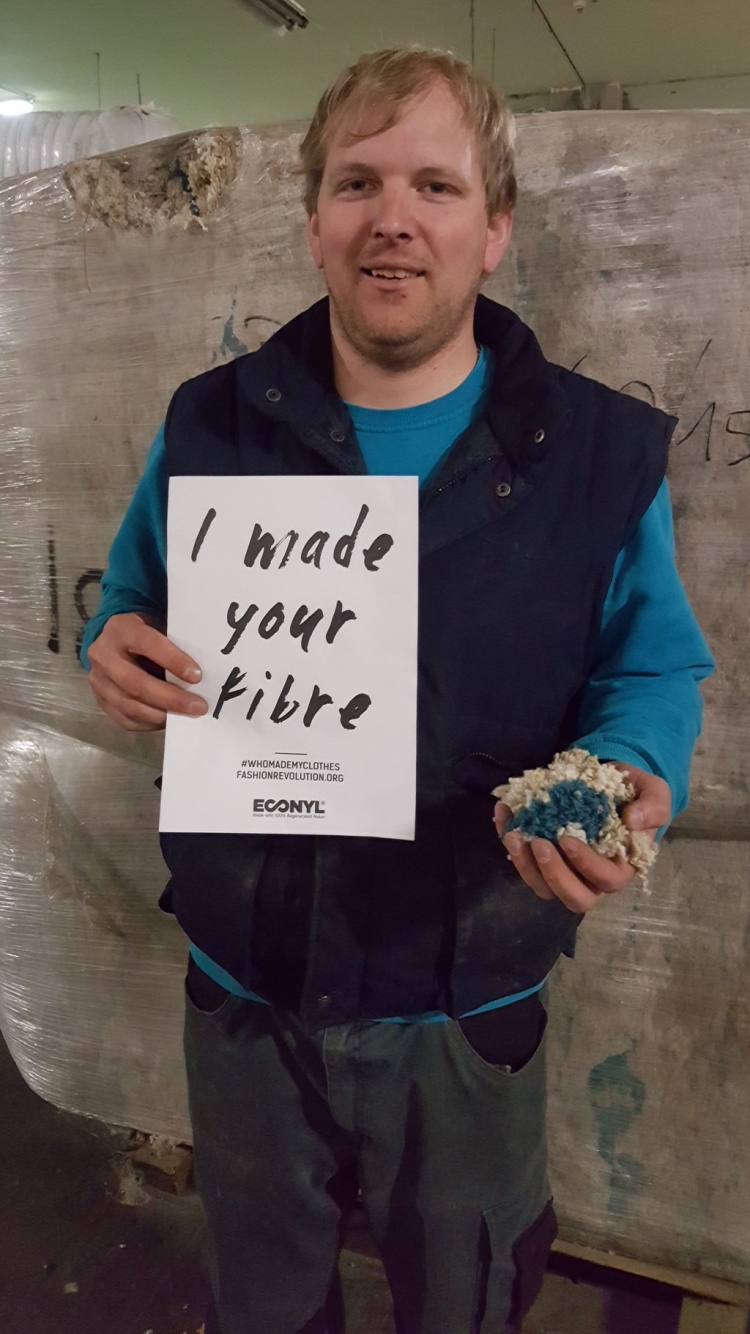

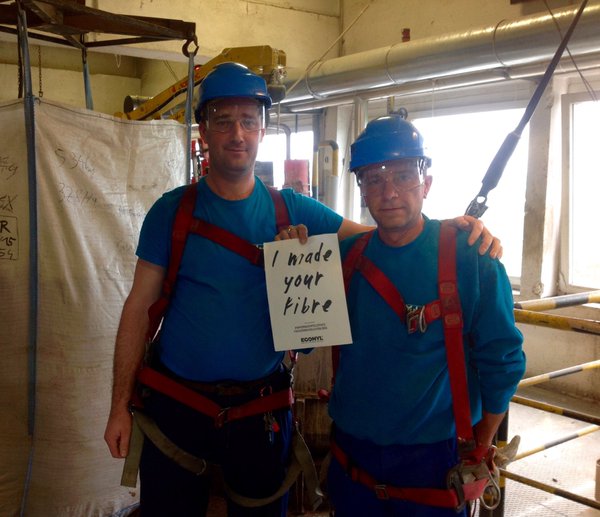

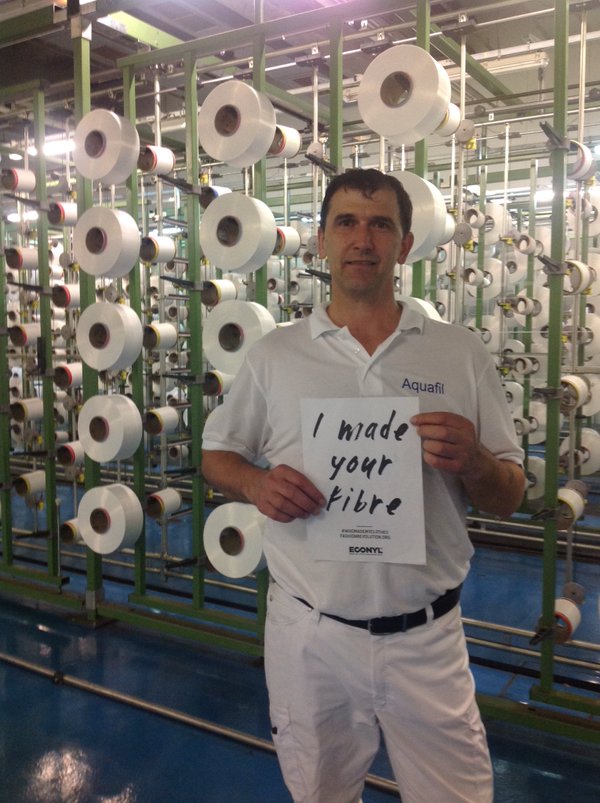

And here are the people who made my swimsuit …

This is Paolo in the ECONYL plant He prepares nets for regeneration

This is Ivo with some nets to be turned into ECONYL yarn

Jan with some carpet fluff, the upper part of old carpets that is regenerated into ECONYL yarn

Denis & Mladen they are at the very beginning of the ECONYL regeneration process

Jozica works in the chemical lab. She checks the waste material that will become ECONYL yarn

Mirko keeps an eye on the spinning to get the best quality ECONYL regenerated yarn in Slovenia

You can always find Boro around the bobbins of ECONYL regenerated yarn to check quality

Bobbins of ECONYL regenerated yarn wouldn’t get to clients if it wasn’t for Muamer

And all of this recycled fibre then gets made into gorgeous AURIA swimsuits

I’m really happy to see that ECONYL is able to answer the question #whomademyclothes and show me the faces of everyone who has helped to make the fibre for my new swimsuit #imadeyourclothes.

24 April is the most important day for fashion. But not because it’s Fashion Revolution Day. It’s because over 1000 men and women, with families, hopes and dreams just like us, lost their lives while making our clothes.

Did you know that 80% of our fashion is made by 18-24 year old young women around the world? Sadly the only time we hear about these millennial makers is when tragedies such as Rana Plaza occur.

When we ask more about them, we can change their lives. Let’s never forget Rana Plaza and keep asking our favourite brands #whomademyclothes?

#whomademyclothes……..do you ever wonder? We are super excited that Fashion Revolution has opened the doors for people to explore this question and find answers. We are happy to share our story about the manufacturing of our Gypsy and Lolo accessories.

It all starts in North Carolina where our fabric is made from recycled cotton yarns. Here are Rodger and Jonathan working on one of the knitting machines.

Once the fabric is made it is shipped to our cutting factory in Oakland CA where it is cut by Daniel. Below is a photo of Daniel and his assistant rolling out fabric on the cutting table.

All the cuts travel from Daniels to our sewing factory in Alameda, Ca.

That’s about a 3 mile trip!

Angela and her sister Connie have owned and operated their small sewing shop in Alameda for 27 years. They employ 12 people all of which are paid and treated fairly. Both Angela and her sister Connie work alongside their employees, ensuring that they all have a good environment to work in. We often visit their factory with our 2 children and all of the workers greet them with smiles and treats.

Here is Angela working on a pair of our wrist warmers.

This is Chang sewing our scarves.

Karen doing the last inspections on our hats and getting them ready to ship to our warehouse in Arcata, Ca.

Now that all of our accessories are done being sewn they are ready to be packed and shipped off to stores across the USA. We do all the shipping from our warehouse in Northern CA. Here is Gypsy’s mom Nancy packing the boxes.

Thanks for caring and supporting brands that are ethical, eco friendly and transparent with their manufacturing process.

Sincerely, Loic (Lolo) and Gypsy

By Balmi Chisim, Solidarity Center

More than 1,100 garment workers died on 24 April 2013 when the Rana Plaza building collapsed in Bangladesh, a preventable disaster that injured thousands more workers in the world’s worst industrial accident in years.

Yet their lives likely would have been spared ‘if any of the factories (in the building) had a union’ says union leader Salma Akter Meem. Salma made her observation as she took part this month in a 10-week-long Solidarity Center fire safety training program, one of nearly a dozen such programs the Solidarity Center has held in the past two years.

Salma, 26, started working at age 14 in the garment industry. She says the Rana Plaza building collapse made her co-workers aware of safety issues, and they formed a union September 2013 so they could have a collective voice to create positive changes in their workplace, including making their factory safe.

Blocked from Factory for Trying to Form a Union

Forming a union was not easy, she says. The employer refused to recognize their union even after it received official government registration, which is required in Bangladesh. Employers retaliated against union members, especially against workers on the factory union’s executive committee, Salma says.

‘I was harassed and my union members were banned from entering the factory while we raised our voices and brought attention to the Accord that there was excessive machinery load on the floor and safety issues’ says Salma, who now is general secretary of the factory union.

The Bangladesh Fire and Building Safety Accord, a legally binding agreement in which nearly 200 corporate clothing brands paid for garment factory inspections, was set up after international outrage over the Rana Plaza and the Tazreen Fashions Ltd. tragedy five months earlier, in which more than 100 garment workers were killed when the factory burned down. Since the Tazreen fire, 34 garment workers have been killed in fire incidents and 1,023 workers injured, according to data compiled by the Solidarity Center staff in Bangladesh, according to data compiled by the Solidarity Center in Dhaka, the capital.

Following inspections mandated by the Accord, dozens of garment factories were closed for safety violations and pressing safety issues were addressed.

Standing Strong Together and Winning

Even though some workers were not allowed to work after they formed a union, Salma and her co-workers did not give up in the face of such employer resistance. With assistance of the Solidarity Center and the Bangladesh Garment and Industrial Workers Federation (BGIWF), to which their factory union is affiliated, workers got their jobs back with full compensation for the time they were prevented from working.

Negotiations and discussions with management, finalized in February 2015, have resulted in positive changes, Salma says, with workers getting a wage increase, maternity benefits and safe drinking water. The factory now is clean, has adequate fire extinguishers on every floor, and a fire door has replaced a collapsible gate.

“Changes are possible if you have union and you can make it work.”

Back at the Fire and Building Safety class, Salma says she is ‘learning here not only for me, but also for my factory and family’. She says if workers are safe in a factory and not afraid to raise their voices for a safe and healthy work environment and living wages to support themselves, their workplace contributions will increase, benefiting the employer—and the country.

Header photo: Bangladesh garment workers take part in Solidarity Center fire safety training. Credit: Jennifer Kuhlman/Solidarity Center

Carol is the Quality Control Supervisor at SOKO Kenya in the Rukinga Wildlife Sanctuary. She manages a team of 5 people, and her daily responsibility is to make sure that all of the factory’s production is up to standard. “I guess you could say I’m a perfectionist, “ says Carol, “at the factory I like to make sure everything is checked with great care and detail.”

Carol is from the Vihiga county in Western Kenya. After completing primary school she moved to Mombasa on the other side of the country in the hope of getting a high school education. Unfortunately her mother passed away a few months after she left. Carol’s grandmother looked after her siblings and cousins, but she could not afford the school fees. Carol found work as a cleaner for a local coastal family and sent money back to support her grandmother. In 2002 she met her husband and became pregnant with her first child. She was 16 years old. Without family around her to help to look after her baby, she was forced to quit her job while her husband supported the family with his income as a bajaj driver.

It was in 2009 that Carol’s prospect’s changed. She heard about SOKO Kenya and she applied for a job as a helper. Over the past six years, through hard work and an eagerness to learn, she has been promoted to a supervisor role. “Employment has not only empowered me but also it has motivated me in so many ways,” Carol says. “My dream is to become a designer.”

Last year Carol was awarded a scholarship to the UK, and she spent two months attending a pattern drafting and garment construction course. “I got to experience a life which is so different to what I am used to. I felt like the UK was a different world, and it made me wish that Kenya would one day be a developed country like that.”

“I attended other conferences, particularly about design, and it inspired me to start thinking out of the box. I found out that there are all different types of designers, even ones who design road signs! When I came back after two months I had so much knowledge to share with everyone, and endless stories to tell. My heart was filled with joy, my face full of smiles and a song of thanks to God for making this dream come true.”

The SOKO factory is based in an area which suffers from the lowest employment rates in Kenya. There are high rates of prostitution, HIV/AIDs and wildlife poaching. SOKO aims to empower women by providing employment and training in a safe and fair environment. Through this we hope to establish an ethical and sustainable workplace which will benefit the local people and the wildlife both now and for future generations.

80% of our fashion is made by women who are only 18 – 24 years old. Sadly we only hear about these women when terrible tragedies occur, be it the Rana Plaza disaster in Bangladesh in 2013, the horrific fire at Ali Enterprises in Pakistan in 2012, or Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in New York in 1913. The hopes and dreams of the women behind our fashion are eclipsed by heartbreaking headlines that hound the fast fashion industry.

Made in Pakistan is the story of two incredibly resilient women who make our clothes. They don’t want our pity. They want us to know them. We hope this short will move you to care about them and ask #whomademyclothes.

Rubina: I am 22 years old and wanted to be a doctor. Then my father got sick, so here I am, many years later, still at a factory stitching college sweatpants and hoodies that go to America. I don’t want you to feel sorry for me. I used to be shy and scared in the factory environment. But after all the injustices I’ve seen happen here, I’ve become a labor organizer. I go to management to demand that we are not harassed, paid on time, given proper food to eat. You would not believe the things I have seen. Stitching all day long my mind wanders and I think about you often. You having fun, wearing these hoodie on campus. I wonder if you think about me ever? The woman who made that for you. I am taking English classes at night. So that one day I can at least get an office job.

Lubna: After my husband left me and my infant daughter, I had to find ways to care for her and my aging parents. So here I am, many years later working at a garment factory. As I pull threads out of hoodies and do the final inspection, I sneak glances at the clock. My days are long and I miss my daughter so much. The other women on the line help me get through my days. We share secrets and the grief that is buried deep in our hearts. When the sun starts to set, its my favorite part of the day because I get to go home to my daughter. I don’t have very many dreams of my own anymore. I just hope for a better life for my daughter. I often imagine university students hanging out, wearing the hoodies that I helped make. I hope you know that my daughter and my life are woven into the threads of your hoodie.

Making of the film: Made in Pakistan is a part of Remake’s Meet the Maker series. We traveled and visited fabric mills, factories, dormitories and homes throughout the world in search of the women who make up fashion’s supply chain. So far we’ve been to Haiti, India, Pakistan and China, to sit down and eat meals, listen and learn about the triumphs and the heartaches of the women who make our clothes.

This film is personally very meaningful to me. I was born and raised in Karachi, Pakistan. I have for the last decade worked across brands, factory managers, government and unions leaders to invest in the lives of the people who made our clothes. We were fortunate to have partnered with an amazing Pakistani film crew. Our cinematographer Asad Faruqi and producer on the ground Haya Iqbal were thoughtful and persistent in capturing this story (and their recent documentary A Girl in a River has just won an Oscar!).

We hope you enjoy a glimpse into Lubna and Rubina’s life and think about them the next time you put on a hoodie or a pair of sweatpants.

80% of our fashion is made by women (mostly 18-24 years old) but we only hear about these millennial makers when they’re associated with a tragedy like Rana Plaza in Bangladesh in 2013 or the infamous Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in New York in 1913. Their stories are eclipsed by heartbreaking headlines that hound the fashion industry.

But there is another part of this story. It’s a story of hope. Remake has traveled to factories and dormitories throughout the world in search of the women who never make the headlines. Kashmiri who opens the yarn to make it into fabric. Maud and Rubina who stitch our blouses and jeans together. Anju who pulls out loose threads and inspects everything to ensure perfection. Each has a story and a hope for a very different future.

Meet the women behind fashion’s supply chain — we followed them from Haiti to Pakistan to China — and asked each of them to share a message to you, the end shopper. These are their stories:

Kashimiri, Yarn opener, Panipat, India

I am 25 years old and already have 4 children. I sit crouched on the floor all day, opening spindles of yarn which go on to become fabric. Panipat has a lot of needs. Open sewers, flies and trash everywhere. Only recently my children starting going to school. I now hope that they will have a better future. Go on to be somebody. I hope you can see their faces in the threads of your fabric.”

Rubina, Hoodie Sewer, Karachi, Pakistan

I am 22 years old and wanted to be a doctor. Then my father got sick, so here I am, many years later, still at a factory stitching college sweatpants and hoodies that go to America. I don’t want you to feel sorry for me. I used to be shy and scared in the factory environment. But after all the injustices I’ve seen happen here, I’ve become a labor organizer. I go to management to demand that we are not harassed, paid on time, given proper food to eat. You would not believe the things I have seen. Stitching all day long my mind wanders and I think about you often. You having fun, wearing these hoodie on campus. I wonder if you think about me ever? The woman who made that for you. I am taking English classes at night. So that one day I can at least get an office job.

Maud, Jeans Sewer, Ouanaminthe, Haiti

The factory across from the Massacre river is like paradise, with its lush green trees and paved roads. I’ve been sitting down sewing your jeans here for five years. Recently my back and neck has been hurting a lot more. But without this job, I have no way to support myself or my six siblings. After a long day, I walked across the river into my community which is pitch dark at night. There is no electricity or running water, just human need everywhere. I want to save enough to go back to university and study computer science. I want you to think about your sister Maud in Haiti, when you put on your jeans. On dark sad nights I play on Facebook with my phone and dream of the day I can be just like you.

Zheng Ming Hui, Quality Assurance, Guangzhou, China

At 19 I left my village to experience the excitement of city life. Here I am three years later, still at the same factory. I work 12 hours a day, looking at beautiful, bright patterns to make sure that there are no defects. My mother wishes I would call her more. But mostly I miss my grandmother. I only get to see my family once a year for Chinese New Year and mom makes the biggest feast. My entire life is the factory. I live in the dorms with three roommates, work all day only stopping to eat at the cafeteria. On my one day off, I am too tired to do much so I play with my phone. At night I dream of bungee jumping. I want to find someone to fall in love with and travel the world for work, taking pictures and telling stories. But for now, I am here, making sure your clothes look nice. I picture you and I am sure you look BEAUTIFUL!

Anju, Fabric Inspection, Delhi, India

I once dreamed of a life that was very different. Where I could finish my education and become a teacher. Everything changed when I was 15 and married to a man with few means. For the last 10 years, I’ve been working in a factory instead. I am proud to be an equal bread winning partner with my husband and to know that my hard work allows my children to go to school. I stand on my feet all day, pulling loose threads out of finished blouses and tops. Making sure they are perfect for you. I want you to know that I recently took a health education course on making nutritious meals with little money. I now teach what I’ve learned at my children’s school on my day off. I guess my dream of becoming a teacher has come true after all.

A 100 pair of human hands touch our clothes before they get to us. Each one of these mothers, sisters, wives and daughters are fierce and hard-working. Dreaming like us to be healthy, happy and financially secure.

Share these stories on Twitter and Facebook with your favorite brands and say: I want to know the invisible people #whomademyclothes.

Together we can #remakeourworld

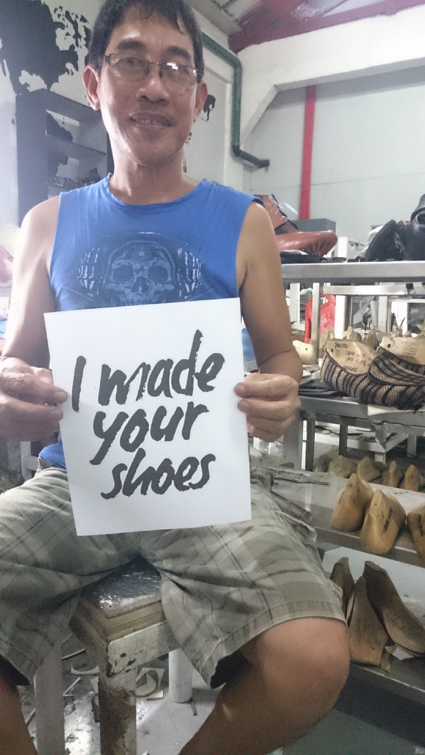

Fashion Revolution is here to connect makers and producers to consumers. In the Philippines, we have teamed up with Risqué Designs to demonstrate to the fashion industry that this is possible. Risqué Designs make fabulous made-to-order shoes from various local materials and supports weaving and artisan communities through sourcing everything locally.

Their shoemakers may also appear at their shop where shoppers can get detailed information on the products they made. Which is impressive! Not many brands do this! We encourage more companies to give their makers the opportunity to meet customers and connect with them. This is a great way to establish brand reputation.

Below are the stories of the shoemakers of Risqué Designs.

JOSEPHINE (NENETTE)

Role: Sample Maker

52 years old

When did you start making shoes?

In the year 2000 until present

Tells us how you progressed into the role you have now.

When I first started, I was stitching shoes, I was a seamstress for Puma. But as I observed my colleagues who had other roles I wanted to take on bigger tasks in the assembling process.

What are your hopes and dreams in the future?

I hope to have a shoe factory of my own and be able to designs shoes like Tal does.

How long have you been working with Risqué Designs?

Just over a year

What makes working with Risqué Designs unique from your previous work places?

I am able to help Tal in the decision process of choosing appropriate materials and Tal’s designs are uncommon and are different from mainstream shoes these days. It’s also nice to work in a place that has a friendly atmosphere, where we could be a family to each other and help each other develop skills and expertise. I am enjoying my work here!

What is the hardest part of your job?

When a design has intricate details

What is your favorite part of the job?

When I am making sandals and flat shoes

Rudolfo (Rudy)

Role: Pattern Maker

44 years old

When did you start making shoes?

When I was 14 years old until now.

How did you start?

I started stitching shoes in 1983 and connecting the soles to the body of the shoes by 1984. From 1996 until today, I do everything.

What is the hardest part of your job?

When there are complicated parts to assemble. You need a lot of patience!

Do you like working with Risqué Designs?

Yes, I like it here.

ROMY

50 years old

How did you start making shoes?

I started when I was 18 years old, like others I was also stitching parts of the shoes together.

What are your hopes and dreams for the future?

I want to be better in making shoes and to master the process.

What do you like doing in your job?

I like making men’s shoes and casual shoes.

If you are in Manila, Philippines and want to explore the city, why not drop by at Risqué Designs’ shop at the ground floor of Glorietta 3. The team is more than happy to meet you! Opening times are from 10am-9pm from Sundays to Thursdays and 10am-10am on Fridays-Saturdays.