Phann is a 40-year-old garment worker living in Phnom Penh with her husband, a security guard. Their rented room is typical for a garment worker—encased by concrete walls and covered by a tin roof with one bathroom and no kitchen. Since Microfinance Opportunities (MFO) began interviewing her in July, Phann has reported working long hours, making products for major clothing brands. She has worked 61 hours a week on average, including three weeks when she worked more than 70 hours, well above the 60-hour week maximum mandated by Cambodian law. Despite her illegal hours, she is paid 66 cents an hour according to our data, falling just short of the legal minimum wage of 67 cents per hour.

Phann, like the other 180 women participating in MFO’s Garment Worker Diaries in Cambodia, is hoping that 2017 will bring new money as the Government of Cambodia has mandated that factory owners increase the minimum wage from 67 cents to 73 cents per hour, equivalent to an increase from $140 to $153 per month [1].

Most of our diarists are positioned to receive that increase—approximately 68 percent report earning the minimum wage, if not higher. The other 32 percent of workers stand to be disappointed, according to a preliminary analysis of the data. They earn only 57 cents an hour on average, so far below the minimum wage that an almost 30 percent increase in their wages is unlikely.

Not only are they receiving less than the minimum wage, but the ways in which their earnings are calculated are often opaque, and their payment schedules are inconsistent. For instance, Mao—a 28-year-old garment worker living in Phnom Penh—received checks showing that she earned the minimum wage. During our first interview, she reported that the factory paid her $140, but she could not tell us how many hours she worked during the pay period. At that moment, we were hopeful she would be one of the garment workers who received fair wages for her work. Her next check was for $137.50, but she worked 250 hours during the pay period which equates to only 55 cents an hour. She fared better on her next paycheck, earning 68 cents an hour for 227 hours of work. However, by the time she received her fourth check, any pretense that she was receiving fair wages had disappeared. She earned $90 for 200 hours of labor, equal to 45 cents an hour.

At least Mao’s employer paid her. Chen, who works in another factory in Phnom Penh, worked 194 hours but was never paid as her employer absconded. She and her colleagues did everything possible to stop him: they attempted to block the exits to the factory to prevent his escape and sought a court order to detain him, or at least seize the assets of the factory, but those efforts proved unsuccessful. As of this writing, she has still not received any compensation for her work.

For women like Mao and Chen, and women like Phann who are paid fairly but work in excess of what is allowed by law, an increase in the minimum wage will not be enough to ensure their dignity. Brands and the Government of Cambodia must enforce the regulations that ensure fair wages and working conditions.

There has been slow progress in this regard, and a lack of transparency in the supply-chain makes evaluating the pace of progress difficult. Organizations like the Solidarity Center and Human Rights Watch are investigating working conditions to bring better transparency to the sector, but their main leverage point is to indict the reputation of the brands, a real but indirect threat to brands’ bottom lines. Consumers, with their ability to directly impact brands’ by altering their purchasing patterns, are the ultimate leverage point. For change to occur, you as consumers must demand transparency and fairness throughout the supply-chain.

To ensure dignity for these women, you must demand a fashion revolution.

[1] The legal minimum wage in Cambodia is $140 per month and is not typically reported as an hourly rate. The legal regular work week, before earning overtime, is 48 hours per week. For an average month, this equates to 67 cents per hour. The government has set the minimum wage in 2017 at $153, equal to 73 cents per hour.

The Garment Worker Diaries is a yearlong research project, led by MFO and supported by C&A Foundation, which is collecting data on the lives of garment workers in Bangladesh, Cambodia, and India. Fashion Revolution will use the findings from this project to advocate for changes in consumer and corporate behavior and policy changes that improve the living and working conditions of garment workers everywhere.

On the 12th Day of Christmas

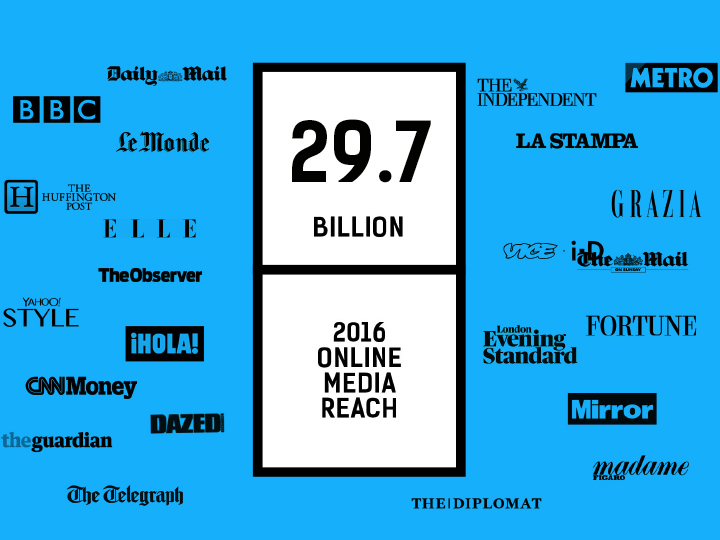

12 months of press coverage.

1619 press articles generating Circulation (Potential Viewership) of 29.7 billion, according to Meltwater press figures.

On the 11th Day of Christmas

11 steps to creating a revolution.

Blueprint for Revolution by Srdja Popovic is one of the books and reports reviewed in Fashion Revolution fanzine #001 Money Fashion Power. Through 72-pages of poetry, illustration, photography, graphic design and editorial, this collectible zine explores the hidden stories behind your clothing, what the price you pay for fashion means, and how your purchasing power can make a positive difference. Published in January and available for pre-order now.

On the 10th Day of Christmas

Business of Fashion published the 10 Commandments of New Consumerism

BoF outlined the 10 factors that define new consumerism and what this change in shopping habits could mean for fashion brands and retailers. BoF said “For decades, a brand’s only priority was to create the best possible product at the most competitive price to ensure sales. But as consumers develop a more comprehensive understanding of issues like sustainability, authenticity and transparency, brands and retailers are being forced to change the way they sell in order to survive”. Coming in at no. 1 in the 10 Commandments for New Consumerism is: Provide Transparency Into Your Business Practices.

On the 9th Day of Christmas

92 countries around the world were involved in Fashion Revolution Week in April 2016.

And even more countries have joined the movement since April. Find out what’s happening in your country.

On the 8th Day of Christmas

Over 800 Fashion Revolution events around the world.

Clothes swaps, film screenings, exhibitions, fashion shows, panel discussions, selfie walls, Fashion Question Time in the UK Houses of Parliament and more. Find out what’s happening in your country on our Events page.

On the 7th Day of Christmas

7th most successful global PR campaign in The Global SABRE awards.

The Global SABRE awards honour the world’s 40 top public relations programs of the past year. Ketchum came 7th for the Fashion Revolution Germany video, €2 T-Shirt – a Social Experiment which has received over 7.6 million views to date.

On the 6th Day of Christmas

6.30am Wake Up, 1.30am Sleep.

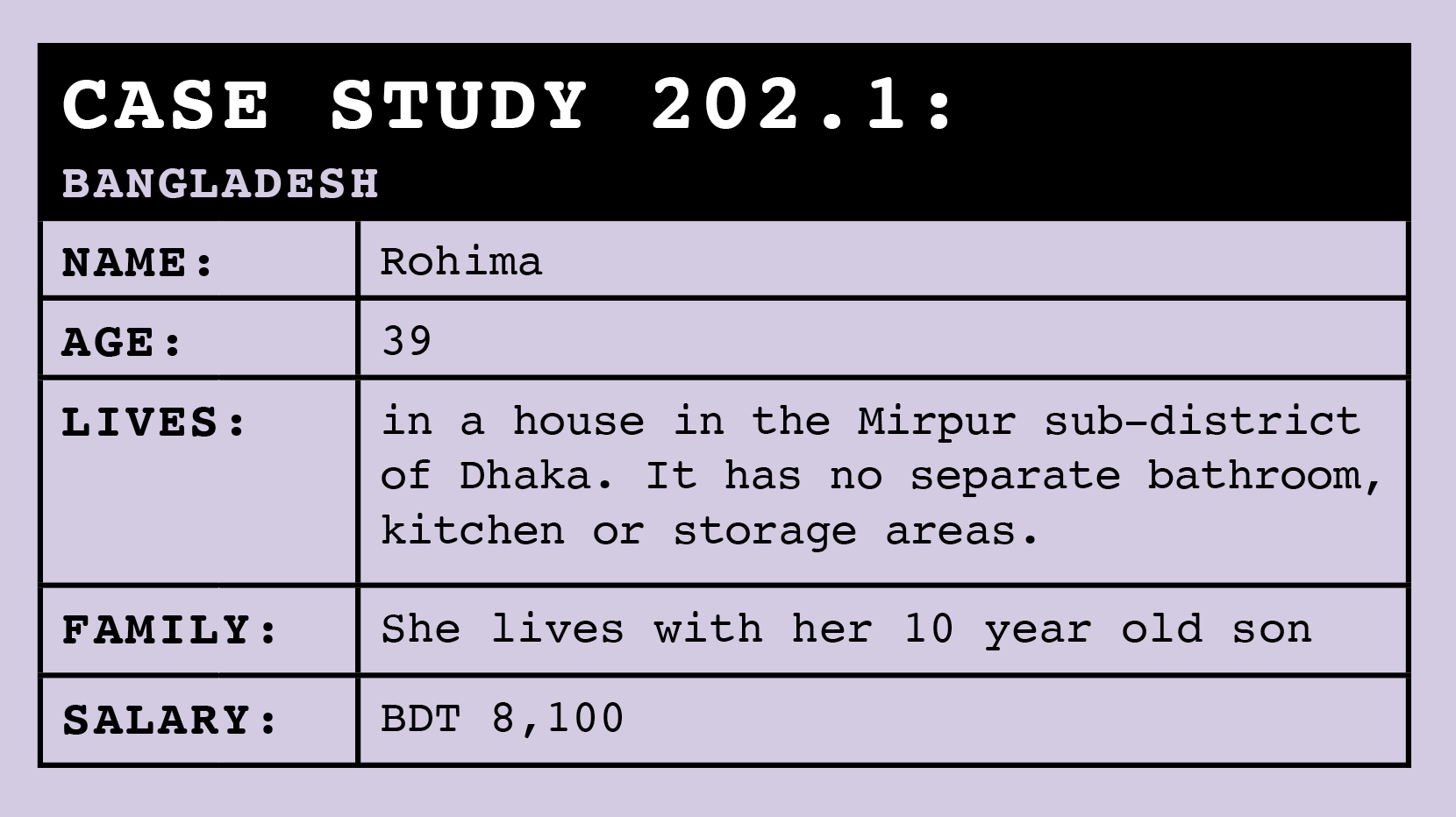

Garment Worker Diaries, lead by Microfinance Opportunities and funded by C&A Foundation, is gathering firsthand accounts of 540 garment workers in Bangladesh, Cambodia and India. Researchers are collecting information on what these women earn, spend, put in and take out of their savings, borrow from others, and lend to others. We are also learning about their daily schedules and what kind of conditions they’re working in at the factory. Over the course of 12 months we will have a better understanding how these garment workers survive on low pay and deal with problems such as chronic pain, harassment or illness. Find out more the daily routine of a garment worker, how much she earns and how much she spends in a week in our Money, Fashion, Power fanzine.

On the 5th Day of Christmas

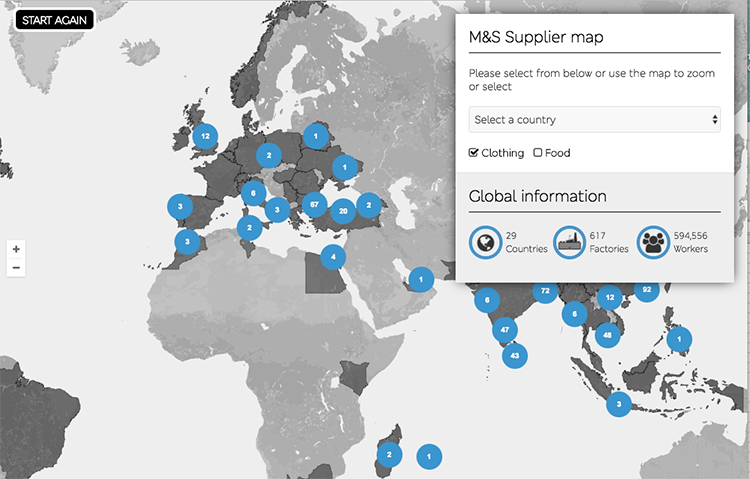

5 out of the 40 brands on our inaugural Fashion Transparency Index were publishing their factory lists.

However, since April we have seen Gap, Marks and Spencer, VF Corporation (who owns The North Face, Vans, Wrangler and others) and Jeanswest publish a list of the factories where their clothes are stitched and Inditex, who own Zara, Massimo Dutti and Pull and Bear among other brands, has published a list of the facilities where its clothing is dyed, washed, printed and where leather is tanned.

The 2017 Fashion Transparency Index will cover 100 of the world’s largest fashion brands.

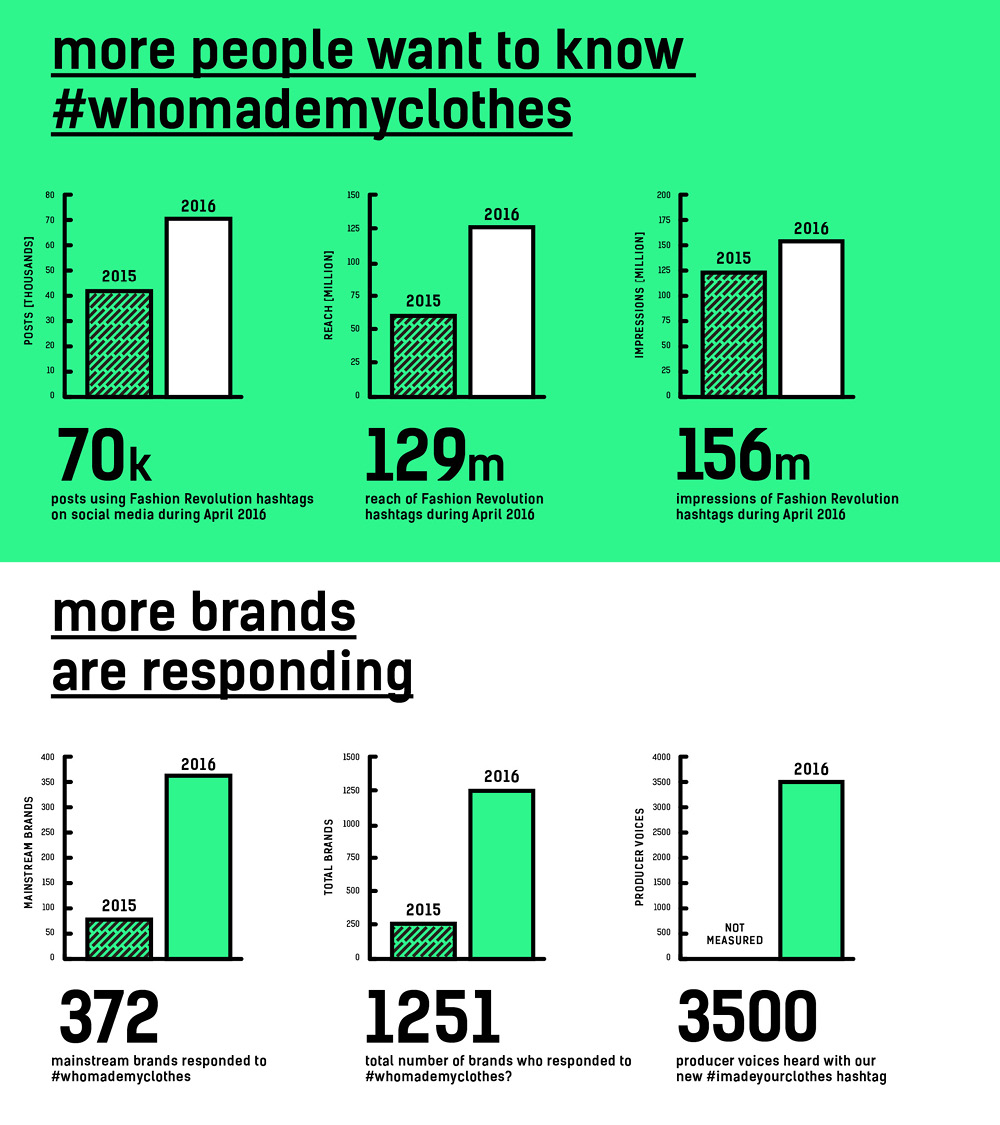

4 campaign hashtags used during 2016

#FashRev (general), #whomademyclothes (ask to brands) #imadeyourclothes (producer photos and stories) and #haulternative (alternative ‘hauls’) generating 156 million impressions during Fashion Revolution Week.

For 2017 our hashtags will be #FashionRevolution, #whomademyclothes, #imadeyourclothes and #haulternative.

On the 3rd Day of Christmas

3.11 million views of Fashion Revolution videos in 2016.

Fashion Revolution Brasil’s Fashion Experience: o outro lado da moda, Fashion Revolution Germany’s The Child Labour Experiment, #Haulternatives by Cutie Pie Marzia and Maddu, plus over 60 more #Haulternative and Love Story videos posted by people around the world.

Find out how to make your own #Haulternative and Love Story videos on our website.

On the 2nd Day of Christmas

2 founders of Fashion Revolution, Carry Somers and Orsola de Castro were named amongst the most influential people in London 2016.

Carry Somers and Orsola de Castro were listed in the Evening Standard’s Progress 1000 Awards in the Equality Champions category which included the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge, the Duchess of Cornwall, David Beckham, Richard Gere and Stephen Fry,

On the 1st Day of Christmas

One global campaign changing the fashion industry.

Please be a part of the Fashion Revolution and help to make our voice even louder in 2017. Be Curious. Find Out. Do Something About It.

Help us launch our 2017 theme MONEY, FASHION, POWER.

Please donate to keep strengthening the movement.

By Allison Griffin for Remake

Few things are more powerful than a room full of women who have something to say.

As part of our Remake Journey we traveled 2 hours outside of Phnom Penh along dirt roads to a small school in the middle of rice fields, one of the few safe places makers are able to unite to talk about their rights without the police breaking up the meeting.

This gathering was hosted by Solidarity Center, to help makers fight for their rights. We learned that when big factories agree to cheap prices and tight deadlines, they often can’t meet these demands. So they ship orders off to fly by night operations–dark, dingy subcontracted factories where the conditions are the worst.

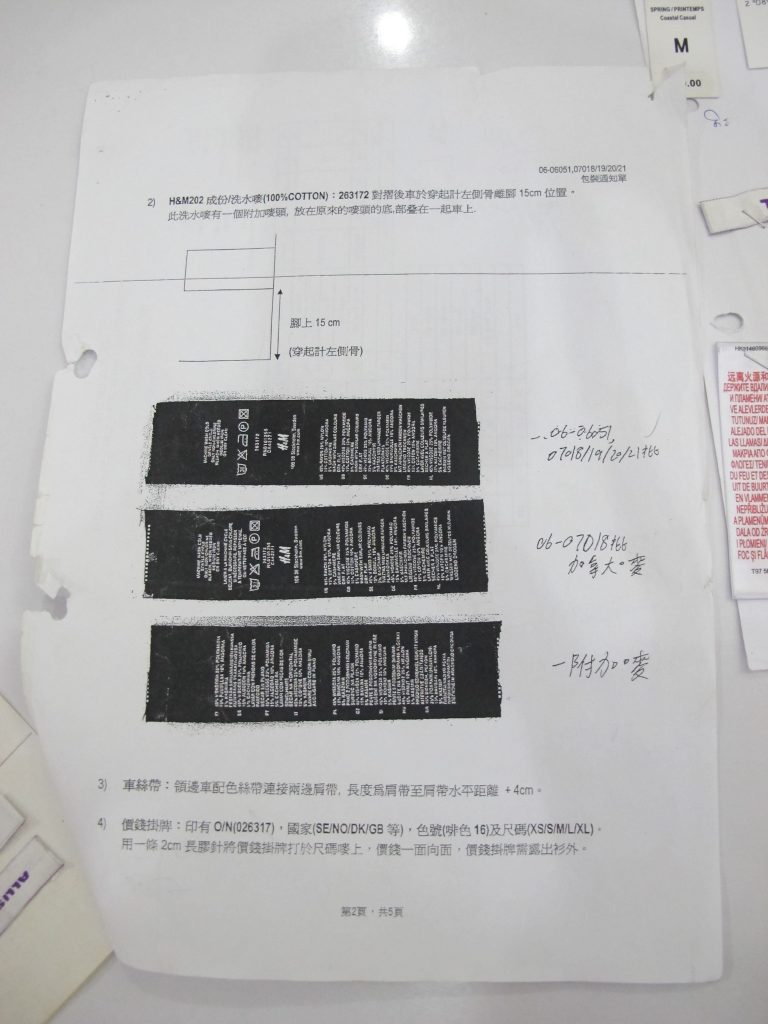

The women we met had sneaked out labels from the brands they illegally sew for including Zara, H&M and Tommy Hilfiger. It was dangerous for them to sneak these photos and labels out but they did it anyway, in the hope that we and you as readers would help them, to ask these brands pressing questions about why they worked such long hours for so little.

I had the honor of sitting down with one such maker, Char Wong. This is her story:

I grew up in a family of eight children raised by a single mother. I was a farmer before working in a subcontracted garment factory. I found work in a subcontracting factory to earn more money and provide a better life for my own family, but the pressure from the daily quotas is stressful and the money is not enough.

I support my 16-year-old son, 10-year-old daughter, my elderly mother, along with my husband who is a farmer. I struggle to feed everyone with the minimum wage and extra $2.50 a day that I earn. My mother has diabetes and her medicine costs $30 a month, over 20 percent of my monthly income. I also want to save money for my children’s education.

wanted a better life for myself and my family which is why I took this work. But life has become harder. I get paid per 12 pieces, but if there’s even one single error in the batch, I don’t get paid at all.

A few years ago, the factory would receive an order for a new design every two or three months, but with the new fast fashion cycles, it now gets more and more new designs in a shorter amount of time. Learning complex designs is very difficult and we get no training. Sometimes it takes two or three hours just to learn and the factory supervisor scolds us for any mistakes. The more time it takes to learn a design, the less time I have to meet the quota and the less money I make. I typically make $5 a day, but with the more complex designs, I only make $2 a day.

Sometimes I cry because I fear I won’t meet the quota and get paid.

Like most parents from all corners of the world, I want a better future for my two children. I hope to pay for their college education so that they can work in Cambodia’s government. Government jobs pay well and do not require hard physical labor. I hope that my children can be government leaders and help improve the conditions and rights of future garment factory makers, just like myself.

I am grateful for organizations like the Solidarity Center, who teach us about our rights. I am learning to speak up more. I want my story and my colleagues’ stories to spread to people throughout the world.

You being here, listening, makes me hopeful.

I definitely felt a lot of girl power throughout the day, both from our own all female crew and the makers we met. These women are not playing victims, but fighting for their rights and educating themselves on their rights. Speaking with Char Wong, I realized that the hopes she has are fundamentally no different from mine–for a fulfilling life. I hope as a designer, I can be a part of the change and that this story moves you to buy better. Together we can #remakeourworld.

From the very beginning, our artisans have always been our partners in positive change and empowerment! The journey of R2R, after all, really started with them. It was through their amazing talent of weaving and this artistry’s capacity to transform lives for the better that R2R became what it is today.

We’re pretty sure you’ve met some of our artisans in our Weaving with the Weavers events or even in our stores –– yes, some of our store ambassadors are artisans, too! But we have a wonderful (but very elusive!) group of artisans we’d love to introduce to you. You don’t get to see them often because these are our workshop artisans! They’re the ones running our humble workshop, assembling your bags to perfection before they land in our stores.

In honor of Fashion Revolution Week, we’re going to take you through our workshop and introduce to you the faces behind our production process!

1. NHING ESTABILLO, WORKSHOP SUPERVISOR

Ate Nhing started as an urban artisan from our Payatas community back in 2008 and since 2012, she’s been in charge of our workshop’s overall production, monitoring targets and making sure her team of amazing artisans create high quality bags and home items for you, our dearest advocates.

Update: Ate Nhing is now our Sales Ambassador! You can meet her in our Trinoma or UP Town Center stores!

2. BERNABE “BING” LOR, TEAM LEADER OF CUTTING

Kuya Bing, as we call him, is the lead of our workshop’s cutting team. Cutting is the very first step in our workshop’s production process! He and his team lays out the foundation of the bags by cutting and preparing the raw materials needed to make R2R bags. Once they’re done, the materials then get passed onto the other steps of our production process!

3. RUFINO “JUN” GAYANILO, JR., TEAM LEADER OF ASSEMBLY

Kuya Jun leads our workshop assembly. Once all the raw materials –– from the handwoven fabric to the bags’ hardware –– have been prepared, he and his team take all these different parts and put them together to build the R2R bags that you own and use today.

4. JIMBO ZIPAGAN, TEAM LEADER OF SEWING

Kuya Jimbo is our workshop’s sewing team leader! He’s in charge of the major and minor sewing of all our bags and home items. Even with that big of a responsibility, he’s one of the people in the workshop who’s always wearing such a huge and happy smile! It’s SUPER contagious, we swear!

5. FLORENCIA “FENCIA” FONTE, TEAM LEADER OF QUALITY CHECKING

Ate Fencia leads the workshop’s quality checking team or QC, as we call it! They’re the ones making sure that each and every bag is up to par with our standards of excellence. We don’t just QC the pieces after it’s done; we also check per stage so we see if each part of the bags were prepared properly, from the handwoven fabric to the cut leather. It’s a very important step of our production process because we always want to deliver high quality pieces to you, our advocates.

In R2R, we believe that fashion can be made in a safe, clean, and beautiful way and where creativity, quality, environment, and people are valued equally. That’s why we think it’s super important to ask the questions: #whomademyclothes, #whomademybags? Join the Fashion Revolution!

Header photo: Carry Somers, co-founder of Fashion Revolution, visits the Rags2Riches workshop in October 2016.

By Allison Griffin for Remake

I am not nervous to speak with you at all. My life has been full of hardships. At this point I am not scared of anything.

We met Sreyneang, a woman who has been working inside a Cambodian denim factory for three years, but has worked in the garment industry for many years. We traveled back to her home with her after her shift in a vehicle similar to a tuk tuk, but larger and less put together. The motorbike pulled a wagon with wooden beams across as seats and you had to balance the weight of people sitting, so that it would not tip over.This or trucks with empty backs are what most of the makers in Cambodia take to and from the factory.

I’ve been sewing since I was 15, my whole life. My husband was a security guard but he got sick. So now my garment maker salary supports him and my two daughters.

I work two jobs. I get up early. Take my kids to school. Then I take transport to the factory. At night I work as a tailor to supplement my income. I usually work until 10 or 11PM at night.

My home village is 3 hours away but I have a small house I bought here, which is unusual because most of my colleagues in the factory are stuck renting from landlords who raise the rent every time our wages are raised.

Her home was at the end of a dirt road and there were a lot of children all around. It was one room with earth flooring and a woven mat and benches, but no beds or indoor plumbing, but it did have electricity. She said she saved up to buy this land and built this house because it was closer to work.

My daughter told me she would drop out of school and start working to help me because she knows how stressed I am. But I said NO. She’s 14. I want her to stay in school and have a different life than me. I want my daughter to go to a school like Parsons and become a designer!

At dinner, she bought water bottles for all of us, which was very kind because they are expensive. While eating dinner, Sreyneang said she usually has only two spoonfuls of rice for dinner. It definitely put things into perspective and you could see the direct effects of low wages.

Sreyneang said she felt blessed that she met us. She wondered if her life would change from this meeting. We parted ways with WhatsApp numbers, big hugs and promises for a future evening together.

The world is round and we are all sisters. I want designers to know of the hardships and suffering in my life, of makers’ lives and the low wages we get.

Fashion design schools have an allure. Many young women in their early twenties get fashion degrees hoping to launch their own lines and drive the aesthetic of a camera-ready $3 trillion industry.

In reality, they enter a competitive market, applying for entry-level design positions in expensive cities. If accepted, they will work long days, under tight deadlines and fluorescent lights, all for salaries as low as $30,000. These graduating designers have little choice but to dive in and hope for a better future.

Interestingly enough, overseas, where roughly 97% of our clothes are made today, there are also young women in their early twenties toiling away on the assembly line. Their wages are low, working hours long, and conditions often difficult. And yet, for these young makers, factory jobs also represent hope for a better future.

Today we buy more clothes and yet somehow pay less for them. This phenomena called fast fashion, much like fast food means the industry cuts corners. What started as a way for more of us to look good on a budget has resulted in a rise in cheap, chemical filled clothes, brought to us by human hands forced to work longer hours for low wages.

But this article isn’t about shaming the fashion industry for building a broken business model. It’s about linking the amazing women on either end of the supply chain – designer and maker – to come face to face, woman to woman, to create a more human centered fashion industry.

80% of the people who are making our clothes are women, usually just 18-24 years old. Their hopes and dreams match ours: to be happy, healthy and see the world. At Remake, we pass the mic back to the women hidden at the other end of the supply chain. We have traveled to Haiti, India, Pakistan and China, to ask her to share her stories.

Our recent Remake Journey to Cambodia was in partnership with Levi Strauss Foundation and Parsons School of Fashion, home to fashion icons such as Donna Karan, Alexander Wang and Tom Ford. We took three of Parsons’ amazing graduating designers:

“As a fashion designer, we are so distant. A lot of our industry uses makers oversees and are so disconnected from them, but these are the people who are creating our work and our designs. So meeting with them and having that more manifested in our heads is a connection we need to be thinking about more.”

Meet Allie Griffin, whose great grandmother used to make our clothes right in NYC’s old garment district. Coming to a prestigious school like Parsons and recently interning at Oscar de la Renta, she feels that in one generation her family has come full circle from maker to designer.

“Fashion effects economies, politics…something you don’t normally think about. But at the end of the day there are people making our clothes, human lives depend on these jobs. That’s why fashion is important to me.”

Meet Anh Le, who designs menswear and has recently interned at American label Thom Browne. Her parents came as refugees from Vietnam, where her family worked in the garment industry. As an Asian aspiring designer, she wants to do right by creating clothes that are ethical and respect the maker.

“I’m really interested in being part of this new generation of fashion designers. We are interested in finding ethical and sustainable ways to participate in fashion. There are a lot of problems that I see, like low wages, underage workers, poor working conditions. I know a lot of my fellow students and I think it’s time to change how we make fashion.”

Meet Casey, who has designed future forward collections in collaboration with Tide and Intel. She is deeply interested in creating more sustainable patterns and textiles in union with factory systems.

Day 1: Tonlé: Zero-Waste Fashion

We visited Cambodia’s first zero-waste brand Tonlé to experience the power of fashion as a force for good. Tonlé provides at-risk women with a living wage, health care and good working hours, while also being good for our planet.

“From the moment we stepped inside the gate you could feel it, it was such a special place. There were a group of women at tables in the front yard knitting together, and they welcomed us warmly with smiles,” recounted Casey. “I spoke with Ny, a transgender male who is in charge of stock and shipping.”

“I think about how the clothes we make go all over the world. I also think that the people who buy from Tonlé really care about us, the people who make them. Most of the makers in the clothing industry come from really poor places, and they work so hard to try to achieve better lives. I want there are more brands like ours so that there are more people who have jobs as good as mine.” – Ny

Day 2: 2,000 People Making Our Jeans

We traveled down a winding bumpy and dusty road to a denim factory on the outskirts of Phnom Penh where jeans are made for every imaginable brand: from JCPenney and Kohl’s to Simply Vera by Vera Wang and J Lo.

Walking down the assembly line, you see hundreds upon hundreds of women, heads down doing fast repetitive motions, backs crunched just like ours over laptops. The sheer volume of stuff, and noise from the machines was overwhelming. All in our quest for cheap jeans.

The denim distressing unit was especially eye-opening.

“All the cuts, wear marks and washes are done by human hands, and these tasks are clearly physically demanding and even dangerous, from all the spraying of harsh chemicals. As soon as our tour ended my brain was overwhelmed with what I had just seen; how could one pair of jeans sell for $20 and have had so many hands work to produce them; the math behind where the money goes does not scream fair at all.” – Casey

That evening one of the denim makers invited us to her home for dinner in a nearby slum. We traveled in the open air truck with her, where passengers need to balance sitting on both ends to ensure the truck did not topple over. Makers in Cambodia have lost their lives in trucks just like this one, which thousands use to get to work everyday.

“I started working when I was 15. Since then I’ve worked at several different factories. My husband is sick, so my $140 a month salary support’s my whole family. I work at the factory all day and then work a second job as a tailor at night. I want my daughters to learn English and go to a school like Parsons. I’ve actually seen New York on TV and maybe someday I can come visit. I want young designers to know about my life. I have suffered but I feel stronger having met my sisters from NYC.” – Sreyneang

Sreyneang’s home was no bigger than two dining tables pulled together, the floor just dirt and the roof sheet metal. Her husband, children and neighbors all crowded in to meet us. Her home may have been small but her heart was huge. When we sat down to eat together, she kept offering us bottled water she had bought for us and took only two spoonfuls of rice. Insisting that we, her neighbors and even the stray dog and cat that stopped by had something to eat first.

“A truly inspiring, loving, and kind soul, I haven’t stopped thinking about her and I don’t think I ever will.” – Casey

Day 3: Sub-Contracted Factories, The Most Invisible People

Few things are more powerful than a room full of women who have something to say. We traveled 2 hours outside of Phnom Penh along dirt roads to a small school in the middle of rice fields, one of the few safe places makers are able to unite to talk about their rights without the police breaking up the meeting.

This gathering was hosted by Solidarity Center, to help makers fight for their rights. We learned that when big factories agree to cheap prices and tight deadlines, they often can’t meet these demands. So they ship orders off to fly by night operations–dark, dingy subcontracted factories where the conditions are the worst.

The women we met had sneaked out labels from the brands they illegally sew for including Zara, H&M and Tommy Hilfiger. It was dangerous for them to sneak these photos and labels out but they did it anyway, in the hope that we and you as readers would help them, to ask these brands pressing questions about why they worked such long hours for so little.

Some of these women made less than a $100 a month despite working all day long. Others noted that they were forced to take pregnancy tests and if it was positive, they were fired.

We learned that some factories pop-up during holiday rushes, then shut down to avoid paying the makers anything once the order is filled. Some of these women had been sleeping outside factories to get their back wages to afford food and rent. One of Solidarity Center’s incredible staff leaders Somalay, said to us,

“We will never stop. We will fight.”

She cares and risks her life, because she’s been there, she used to be a garment maker herself.

“I wanted a better life for myself and my family so I took this work at a subcontracted factory. But life has become harder. I get paid per 12 pieces, but if there’s even one single error in the batch, I don’t get paid at all. I used to make a new design every 2-3 months. Now, it’s two to three new designs per month. The designs are more complicated but we get no training. It’s harder to meet the quota. Sometimes I cry because I fear I won’t meet the quota and get paid. I hope you will help me and my colleagues by spreading our stories to the world. You being here, listening, makes me hopeful.” – Wong Char

“I definitely felt a lot of girl power throughout the day, both from our own all female crew and the makers we met. These women are not playing victims, but fighting for their rights and educating themselves on their rights. Some of the makers dressed up in professional attire, including blazers and heels and every person had a pen and paper they were furiously taking notes with. Speaking with Wong Char, I realized that the hopes she has are fundamentally no different from mine–for a fulfilling life.” – Allie

Journey #5 ended with see-you-laters, not goodbyes. Our designers and makers became friends on Facebook WhatsApp and promised as sisters to keep in touch and fight together to make fashion a force for good.

It takes 100 pairs of hands to bring each of our clothes to life. Next time you go shopping, we hope you think of Ny, Sreyneang and Wong Char and their dedication to our fashion.

We hope you join our movement and buy better from brands like Tonlé. Together we can #remakeourworld

Four million garment workers, mostly women, toil in 5,000 factories across Bangladesh, making the country’s $25 billion garment industry the world’s second largest, after China.

Garment workers generally are paid low wages with few or no benefits and often struggle to support their families. Many risk their lives to make a living.

On November 24, 2012, a massive fire tore through the Tazreen Fashions Ltd. factory in Dhaka, Bangladesh, killing more than 110 garment workers and gravely injuring thousands more.

In the wake of this disaster, garment workers throughout Bangladesh are standing up for their rights to safe workplaces and living wages. With the Solidarity Center, which partners with unions and other organizations to educate workers about their rights on the job, garment workers are empowered with the tools they need to improve their workplaces together.

Learn more about the Solidarity Center’s work in the global garment industry

DISASTER STRIKES TAZREEN

On November 24, 2012, women and men working overtime on the Tazreen production lines were trapped when fire broke out in the first-floor warehouse. Workers scrambled toward the roof, jumped from upper floors or were trampled by their panic-stricken co-workers. Some could not run fast enough and were lost to the flames and smoke.

Hundreds of those injured at Tazreen, like Tahera (above), will never be able to work again. Survivors say they endure daily physical and emotional pain, and often are unable to support their families because they cannot work and have received little or no compensation.

Some 80 percent of export-oriented ready made garment (RMG) factories in Bangladesh need improvement in fire and electrical safety standards, despite a government finding most were safe, according to a recent International Labor Organization (ILO) report.

TAZREEN NOT UNIQUE

The Tazreen fire was not an isolated incident.

Months after the Tazreen disaster, more than 1,000 garment workers were killed when the Rana Plaza building collapsed. Workers were forced to return to the building despite the warnings of structural engineers that the building was unsound.

In the four years since Tazreen, fires, building collapses and other tragedies have killed or injured thousands of garment workers in Bangladesh, according to data collected by the Solidarity Center.

FACTORIES CAN BE MADE SAFE

The Tazreen fire and Rana Plaza collapse were preventable. Workers at Tazreen and Rana Plaza did not have a union or other organization to represent them and help them fight for a safe workplace.

Without a union, garment workers often are harassed or fired when they ask their employer to fix workplace safety and health conditions. They are not trained in basic fire safety measures and often their factories, like Tazreen, have locked emergency doors and stairwells packed with flammable material.

Unions have helped to improve these conditions.

They have joined together to form workplace unions and bargain for safe working conditions, better wages and respect on the job.

UNIONS SAVING LIVES

Worker voices have yielded real results.

Over the past few years, the Solidarity Center has held fire safety trainings for hundreds of garment factory workers. Workers learn fire prevention measures, find out about safety equipment their factories should make available and get hands-on experience in extinguishing fires.

When women workers form unions, they improve their working conditions. Through Solidarity Center workshops and leadership training, more women are running for union office. Women now make up more than 61 percent of union leadership in newly formed factory level-unions.

CHANGE IS POSSIBLE

Salma (below), a garment worker, and her co-workers faced stiff employer resistance when they sought to form a union. With assistance from the Solidarity Center and the Bangladesh Garment and Industrial Workers Federation (BGIWF), to which their factory union is affiliated, workers negotiated a wage increase, maternity benefits and safe drinking water. The factory now is clean, has adequate fire extinguishers on every floor, and a fire door has replaced a collapsible gate.

To learn more about garment workers in global supply chains and how the Solidarity Center supports them, visit www.solidaritycenter.org.

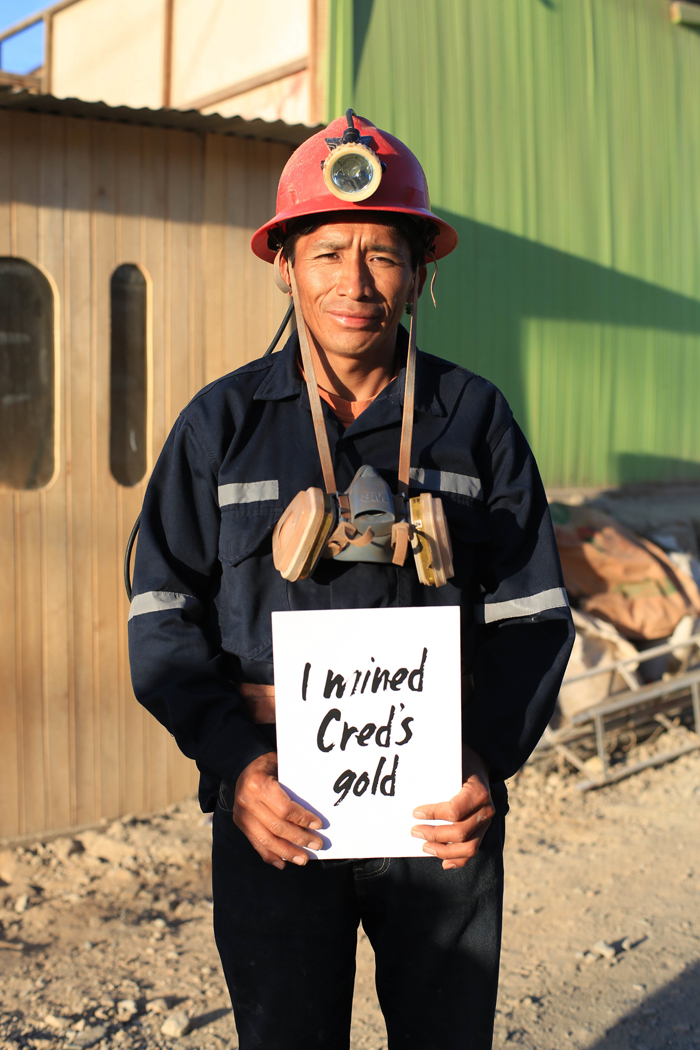

Angela Tatiana Vasquez Rojas has grown up in the small mining community of Santa Filomena since she was four years old. Her father worked in the Sotrami mines from dawn to dusk in order to earn enough to provide for his family and put bread on the table.

Although Angela has many fond memories of growing up in Santa Filomena, it was also a difficult and challenging upbringing. Working in the mines was one of the few jobs in the area and because of her father’s extensive hours he had very little time to spend with her growing up.

Angela spoke to us about the impact working as a miner had on her father.

“Being the daughter of a miner is a bit complicated because you do not get to spend much time with your father” she explains. “Mining wears them down a lot, they get sick and despite the fact that they extract gold they are not rich people as many believe. When they get sick sometimes there is not enough money for treatments. Sometimes there are accidents at work which one cannot survive, and you do not know if they will come out alive or dead.”

The fear for her father’s welfare is one Angela is very familiar with. Thanks to stricter regulations and help from Fairtrade, health and safety and working conditions in the mines have improved significantly over the years.

The organisation Sotrami came to the Atacama Desert mines near Santa Filomena in the 1980s. At that point the village was the home of many people who had been displaced by violence. The group started to work towards eliminating child labour and improving the conditions miners work in to reach international labour standards. The support of ethical jewellers such as Cred Jewellery have helped enable this change by providing demand for fairly sourced gold. Gradually over the years standards improved in the area, but it wasn’t until 2011 that the Fairtrade Minimum Price for Gold and Fairtrade Premium for Gold came into play, meaning that all workers now receive fair wages for their gold and money can be channelled back into the community.

The Fairtrade Premium has completely changed the way that miners and residents of Santa Filomena live. The desert’s high temperatures meant a supply of clean and safe water was unreliable. Water was delivered in a weekly ration of barrels which sometimes arrived unpurified, causing mass sickness. Since their partnership with Fairtrade, the area has improved dramatically. With the Fairtrade Premium fund, the community has experienced a huge change in infrastructure; a new road was built which means water can now arrive by the lorry load, there is now electricity, internet and cable channels, and children have much better access to education and health services.

Angela’s generation is one that has started to reap the benefits of improved conditions, both in the local community and down the mines. She recalls her childhood fondly, acknowledging the hardships but also the positivity and dedication to change her father installed in her. Over the years, many people have worked in incredibly dangerous conditions in order to provide for their families. As things continue to improve, it is important to remember the history of the mines, the resilience of those who worked in them and how improvement affects not only the local community, but is also a reflection on the world as a whole and the growing movement towards ethical and sustainable practices.

“My father, despite the little time he has, has always taught me that one has to move forward and that despite the adversities one must never give up” says Angela. “I can say I had the kind of childhood and adolescence that few can enjoy. Being the daughter of a miner, despite the difficult times, means I grew up knowing that a hero does not always have super powers, but in exchange of that, heroes give their lives for their families.”

Angela is currently working in a village shop in Santa Filomena studying for her University entrance exam. Competition for grants from low income families in the area is fierce, so despite being a top student it is unlikely Angela will have the opportunity to attend university. Cred is dedicated to supporting mining communities and improving prospects for young people. Cred funded Angela’s trip to the UK to give her the chance to experience life in another country and to spread the message of how the Fairtrade Premium benefits so many. This in turn will help raise awareness, so more people will choose Fairtrade which in turn will help university to be more than just a pipe dream for young people like Angela.

The Garment Worker Diaries is a yearlong research project led by Microfinance Opportunities in collaboration with Fashion Revolution and supported by C&A Foundation. We are collecting data on the lives of garment workers in Bangladesh, Cambodia, and India. Fashion Revolution will use the findings from this project to advocate for changes in consumer and corporate behavior and policy changes that improve the living and working conditions of garment workers everywhere.

Dozens of beige colored garment factories line the streets on the outskirts of Phnom Penh. Ten-foot high walls, metal gates, and security checkpoints at the entrances guard the compounds. Early in the morning, garment workers who live nearby leave their homes—often a 70 square foot room with an accompanying toilet—and enter these factories by the thousands to begin their workday. For the next eight to 12 hours, they cut and sew clothes for major clothing labels, who sell the finished products to you and billions of other people across the globe. When the workers emerge, many complain of headaches and chronic pain in their arms and backs, aggravated by the repetitive motions of their work. They perform this routine six days a week, and for their work, the government of Cambodia mandates that factory owners pay them a minimum of $140 per month, or seventy cents an hour based on a 50-hour workweek. The situations in Bangladesh and India are similar. Hundreds of thousands of workers labor long hours in the hope of receiving the minimum wage, which is set at $68 and $105 per month respectively.

Labor rights advocates say that workers in Bangladesh, Cambodia, and India often receive less than the minimum wage. Even if they do receive the minimum wage, the advocates say, it may not be enough for workers who need to pay housing costs and provide themselves and their families with food, health care, and other necessities.

If their wages cannot cover their necessities, how do they survive? Where do they get the money to cover basic expenditures? Do they choose between sending money to their families in rural villages and buying enough food to feed themselves for the week?

What goes on behind those big, metal gates? Do their supervisors encourage or berate them when a major clothing order is due? How frequently do they experience chronic pain from their work? What do they do when they are injured?

We are overseeing field researchers who are asking these questions to 180 garment workers per country in Bangladesh, Cambodia, and India. During the next 12 months, interviewers will visit the same set of garment workers each week to learn the intimate details of their lives. They will ask the garment workers about what they earn and buy, how they spend their time each day, and whether they experience any harassment, injuries, or suffer from pain while at the factory. The interviewers will learn about important events that happen in the workers’ lives too—from birthday parties and weddings to illnesses and funerals for family members and friends.

This data is a treasure trove—imagine what you would learn about a person by asking her detailed questions about her life each week, every week, for an entire year. Our job as researchers is to analyze it objectively and provide answers to the questions of what happens behind those factory gates and, more importantly, what happens after the workers leave them.

Our hope is that clothing companies, consumers, factory owners, and policy makers will be able to use the insights we identify to understand how the decisions they make affect garment workers’ condition. To this end, we are working with Fashion Revolution to get our data in front of change-makers who can influence the global clothing supply chain, the regulatory environment, and the social protections available to garment workers.

One of the most important agents of change is you—the consumer, the driver of trends and clothing orders. Over the course of the next several months, Fashion Revolution and our team will share findings from our project via social media, blogs, fanzines, reports, and exhibitions. We encourage you to stay informed of our work so that you too can be an advocate for the people who made your clothes.

Authors: Eric Noggle and Guy Stuart, Microfinance Opportunities

C&A Foundation is providing financial support for the Garment Worker Diaries. We are collaborating with Fashion Revolution to distribute the results. Our local partners are BRAC (Bangladesh), TNS (Cambodia), and Morsel Ltd. (India).

The garment industry in Cambodia moves a tremendous amount of money. Approximately $5.7billion in clothing and shoes were exported last year, [1] which accounts for as much as a 95% of all exports from Cambodia. Out of the 15 million inhabitants from Cambodia, the garment industry employs around 500,000 people, mostly women.

However, 90% of the owners and 80% of the managers in the garment factories are not Cambodians, but instead they are mostly Chinese, Taiwanese, Malaysian or South Korean.[2] Consequently, most of the revenue resides in a few foreign hands. Not only that, the rumors of corruption and government involvement to support factory owners are well spread out, and the police protection I could sometimes see at the gates of the factories accounts for it. We just need to take a quick look at the appearance of the factory building below, similar to a prison, with surveillance towers and barbed wire all around the walls. In order to visit the inside, special permits need to be issued, but they are very hard to obtain.

The media has already publicized the poor working conditions, but the problem became even more apparent after the protests in Phnom Penh (capital of Cambodia) in January 2014. The garment workers demanded a salary raise from the $80 (USD) to $160 per month, i.e. what workers claim as a living wage to cover basic needs (taking for granted that the worker lives with his/her family, since these wages are totally insufficient to pay a rent). [3] The police were armed in these peaceful protests and the protests ended up with four dead workers as a result of the police brutality. The salaries were increased to $100, far below the aforementioned living wage, and ridiculous if we consider the multi-million dollar profits of the Western brands that feed the system. Currently, around one year after the protests, the salaries can reach $120 (depending on the company), still insufficient when considering living costs in the country.

The protest in 2014 is not an isolated case: the previous year, in January 2013 there was a demonstration in which the workers asked their employer Kingsland (a Hong-Kong owned Phnom Penh based garment factory that supplies to Walmart and H&M), for the delayed salaries from September of the previous year 2012 4. That month of September, due to a decrease in the amount of workload, Kingsland asked its workers not to come to work with the promise of paying a 50% of their salaries during the off work period. However, the company was in bankruptcy and didn’t pay. All managers left or escaped the country – how could that be done without the aid of the government?-. It was not until March 2014 that Walmart and H&M agreed to pay a portion of (not all) of the debt to the workers.

GAP, Adidas, Hugo Boss, Nike – to name a few companies -, all participate in this assault against workers’ rights. It does not need to be on the front page of the newspapers every day. The data is available to whoever wants to know it. The existence of fair trade clothing brands is just the answer to a social issue and a matter of common sense. I want to believe that none of us would ever buy from these companies knowing what is really happening in these factories.

Here I summarize data not only from official sources (again, available on the internet and the provided links), but also from conversations with Cambodians that have worked, work at, or have friends that work in the garment factories:

Excessive overtime

Overtime is a common practice expected from the bosses, on top of the six days a week that garment workers go to the factories. Sometimes, workers need to work two shifts in a row when the production line requires so. Even though overtime is a normal practice in many developed countries, the office conditions are not quite the same. We are not talking about office work in a room with air conditioning here.

Office conditions

The environment in the factories is hot and toxic (and it gets worse during summer time) and deals with dangerous machinery. Even though accidents may not be frequent, they do happen. When they occur, from what I understood from more than one conversation with Cambodians, the managers hide the numbers and threaten their workers to not speak about the accidents.

Low salaries lead to malnutrition

It is a matter of basic math. Let’s take the common $100 monthly salary as the reference. The price of a meal at the food stands usually located at the doors of the factories varies from $0.75 to $1. The meal consists of rice, some vegetables, and a small piece of meat. That is, around $2.50 to $3 just for the three main meals of the day, and food that one would consider meager and of poor quality. In fact, malnutrition cases are frequent among the garment workers. That is, roughly $75 to $90 is the monthly amount required just to eat. Yet for expenses beyond food such as electricity, gasoline, and rent, they only have $10 – $25 left. Obviously, to live on a rent becomes impossible.

Fainting in the factories

Heat, suspended toxic particles in the air, lack or scarce ventilation, humidity, etc. All of that mixed together with malnutrition, has provoked many cases of fainting during working hours.

Most consumers look aside or are unaware of all of these issues when purchasing from one of the many brands that allow this to happen.

This is one of the dozens of trucks packed with people –yet treated like animals- who are driven to the factory, early morning, at 6am.

I wasn’t honored with a permit to enter any factory, but I could speak to some of the workers and workers’ friends. Among them, here below I expose the story of a girl who worked in a factory. She has asked me not to publish her name:

“I worked from July to September of 2014, during the summer holidays at university. The name of the factory is TaiEasy, located in Krakor district, Pursat province. I worked in the “product safety” department, verifying that the machines were in a good condition, but also doing administrative work. I earned $115 per month, and the company additionally provided us with 5kg of rice.

My schedule at work was from Monday to Saturday from 7am to 11:45am, and from 12:45pm to 4pm. However, except for Saturdays, we were asked to do overtime until 6pm or 9pm, depending on the day. And we would not get paid extra. What I could not understand is why the salary of my Vietnamese or Filipinoe colleagues was higher, even double or triple, than for us Cambodians. Most of the time it was us teaching them how to do their tasks when they came in as newcomers. And apart from the salaries, another difference between us Cambodians and the others were the holidays: Cambodians did not have any, just for the Khmer New Year and other national holidays. The other workers from other nationalities did have a few days of holidays, I can’t say how many days though.

My bosses were Chinese and Filipino. Especially the Chinese did not treat us Cambodians –not so much the others- very well. Even though they could not speak Khmer, they had learned a few pejorative ways to refer to us and to call our attention, always threatening us with getting fired when they thought we were too slow. Not only that but also we were only allowed to use the bathroom twice a day during working hours. I left the job when my summer holidays from university were over, but I still have friends working in the factories and the situation has not improved. “

This ex garment worker was back then studying to become an English teacher, and she is working as such now.

Governments from Western nations should be the ones making the move and drawing the border line, banning the import of all goods produced in countries were the workers’ rights and salaries do not reach a minimum or are not transparent. However, this does not happen and companies take advantage of it. For now, it is just in our hands to think twice what we buy, and what we support when buying it. It is a matter of common sense. Let’s not contribute. Let’s make a change.

References

1 http://thediplomat.com/2015/02/cambodias-garment-industryrollercoaster/

2 http://labourbehindthelabel.org/

3 As reference, a normal simple, insufficient- meal from a food stand in Cambodia costs around 1USD, i.e. 90USD a month, which is already the salary of many garment workers.

4 www.business-humanrights.org

Disclaimer: blogposts do not represent the views of Fashion Revolution

Fifteen minutes before the gray, 12-foot gate of the garment factory compound in Myanmar’s Hlaing Thar Yar industrial zone opens to release workers, vendors selling fried chicken on sticks and bags of nuts gather in anticipation. At a designated time, the guards roll back the gate and the vendors push their heavy carts up a steep hill and into the compound. If they hesitate, they are locked out as guards quickly close the gate behind them.

Minutes later, the gate is opened again, and workers rush down the hill to the dirt road, jostling for a place on the open transport trucks that will take them over rutted roads to packed apartments where they pay nearly a quarter of their wages to live. There, they can again access their mobile phones, which are prohibited from factory premises, where the heavy gate locks them behind steep walls from the start to the end of their daily shifts, six days a week.

The scene is repeated countless times across the vast industrial zone, where more than 700,000 workers toil, including 300,000 garment workers. Corporate brands from around the world source their clothes, shoes and other apparel to factories in Hlaing Thar Yar.

Most of the workers, like Lwin Lwin Mar, 34, migrated to Hlaing Thar Yar, 12 miles northwest of Yangon, from other areas in Myanmar. Lwin Lwin Mar came from Irrawaddy Delta in search of a job after the 2008 cyclone devastated the region. Aung Myint Myat, a co-worker of Lwin Lwin Mar from the Bago region, sends money back home to his relatives, as do many factory workers.

Both garment workers helped form a union at a 200-worker factory, standing up to massive employer resistance. Many workers were fired in 2015 for forming the union, but with the assistance of the Confederation of Trade Unions–Myanmar (CTUM), some workers returned to the job.

“The life of workers is very poor,” says Myo Zaw Oo, a CTUM organizer who helps garment workers form unions and helps solve their problems at the workplace. “Workers don’t know about their rights. They are very vulnerable,” he says, speaking through a translator.

Unions Seek to Ensure Labour Helps Shape the New Economy

Last year, Myanmar passed its first-ever law setting a minimum wage—$83 per month—yet employers do not always pay it. Nor do they follow the country’s minimal safety and health regulations or overtime laws, union activists say, making worker education a top priority for CTUM. Even the full minimum wage is not sufficient for workers to support themselves and their families, union leaders say.

After five decades of military dictatorship, political transformation has opened the country in the past few years, and union leaders have sought to ensure that workers are part of the process structuring the ensuing economic and cultural change.

Shortly after he returned to Myanmar in 2012 after nearly 30 years in exile, CTUM President U Maung Maung met with corporate leaders of international brands at a Washington, D.C., conference sponsored by the Solidarity Center and AFL-CIO. The meeting was part of a labor-backed process to ensure corporate accountability and respect for worker rights are embedded at the start of the foreign investment process in Myanmar.

“Labor needs to be involved from the start,” Maung Maung said at the conference. “I would rather have workers’ rights built in from the beginning rather than added on later.”

Helping Workers Form Unions Across Myanmar

Today, CTUM is spearheading union building at a rapid pace, with more than 60,000 workers forming unions since 2012, when Myanmar passed laws allowing the creation of unions. Factory-level union activists like Two Ko Ko, 32, are identified for leadership potential in CTUM, and invited to take part in training to build their skills.

Now an organizer with the Building, Woodworkers Federation–Myanmar, a CTUM affiliate, Two Ko Ko helps workers form unions at cement and plywood factories in Hmawbi, an hour north of Yangon, as well as at construction sites.

“Workers don’t understand that they have rights that are on the books,” he says. “Law enforcement is weak. Unions help make employers follow the laws.”

For instance, says U Lim Mg, union president of a 170-worker clay factory where workers formed a union in 2012, “the union is enforcing the 1951 Factory Act that governs hours and safety.”

The workers ground and mold clay to make floor and roof tiles and are exposed to heavy dust. But until they formed a union, the employer provided only flimsy paper masks. Now, they have proper protective equipment, says Two Ko Ko.

“I have seen much progress since the union has been at the workplace,” says Tin Tin Than, 43, who has worked as cleaner for 10 years at the clay factory. She says their collective bargaining agreement ensures the employer pays the minimum wage and provides transport to and from the factory.

Despite the many challenges, including strong employer resistance to unions and a broad lack of familiarity with fundamental worker rights, Myanmar union activists like Two Ko Ko are determined to help workers achieve decent wages, safe and healthy workplaces and respect at work.

“The best part of my job,” he says, “is when people recognize their rights and decide to form unions.”

By Tula Connell. Find out more at: http://www.solidaritycenter.org

Marcelo Ballesteros, age 50, has worked with animaná for two years now as the link between the company and the local artisans who live in more remote regions of the area. A retired marine, Marcelo now lives in the city of Salta, Argentina and was referred to animaná by a friend of the brand’s founder, Adriana Marina. Since he used to work with his father on pottery and crafted mats on handlooms as a child, he has prior knowledge of handicrafts. When Adriana asked if he would like to act as the connection between animaná and the artisans, Marcelo accepted the offer as an amazing chance to explore and meet new people.

“A day of work for me is never the same as the other.”

Generally, Marcelo’s day begins by preparing the vehicle, writing the waybill and noting the artisans he needs to visit. Sometimes, he explains, you can find them easily and sometimes not. If they are far off in the country feeding the llamas or sheep, it can take up 3 or 4 hours to walk from their houses. At times, Marcelo will sleep in the places he visits if the travel time makes it too difficult to get in and out in one day. Each exertive working day, however, is finished with a big smile because of the adventure lived.

Due to the diversity of locations and unstructured nature of the meetings, it is impossible to stipulate how long each visit will take. Marcelo describes these trips as traveling into the past where there are no mobile phones or televisions — just nature. Kids are the same color as their surroundings and always playing with their herds of llamas or sheep.

“You can feel the flowing streams. The sky is blue, and there is such a cleanness that you forget where you come from. You take some time and think that you are in an amazing place with amazing people, and that is when you realize that the way the village, that is so far from common luxuries, is able to give their touch to the world, is through their crafts.”

Marcelo’s work contributes to the people of the Andes by creating community links and building personal relationships. At times the artisans will travel to Salta and visit Marcelo at his home. He is always ready to assist them and makes sure they are aware of just how much their hard work is valued. What he enjoys most about this bond is being able to talk with the artisans and hear about their lives in the mountains. As he puts it, it creates a link of friendship that goes beyond the commercial.

His hope for the future is that travel routes can be open every month of the year because now, in the rainy seasons, it is impossible to access the remote areas. He also dreams of easier transport for the artisans into the city, as it is only possible now with a pickup truck and at an expensive cost. Still, Marcelo and animaná work tirelessly to bridge the distance between commerce and the local artisans, and through their dedication they are able to foster relationships that extend beyond business.

“Never stop dreaming.” -Marcelo Ballesteros