When Ubuntu Made first came to Maai Mahiu, we found a community of children with special needs and their mothers being mistreated and secluded. The stigma and lack of understanding surrounding special needs in Kenya means extremely limited access to essential services such as education, affordable healthcare, physical rehabilitation, and vocational training. This leads to limited opportunities for social inclusion, many social and economic issues for their families, and ultimately limits their ability to live the life of dignity that they deserve. Ubuntu first created the Ubuntu Special Needs Centre (SNC) to combat this stigma and injustice by providing therapy, education, and vocational training to youth with special needs in Maai Mahiu. Caring for these children had been a full-time job for their mothers, so soon after enrolling their children in the SNC their Mums started a new conversation with the founders: “Now that our kids are out of the house, can you help us do something productive with our time?”

The answer was a fashion line, initially imagined to create jobs for these Mums. Today, those same women have formed into a sisterhood revered in the community: women who provide for their families, purchase land, and venture into their own successful entrepreneurial efforts. Which is why it’s not simply about creating jobs.

“Plenty of people have been given opportunity, but they don’t feel empowered,” explains Zane Wilemon. “There’s something magical about our culture and creating a job within that; it then empowers the whole community.”

This conviction is what led Ubuntu Made to design and launch the Afridrille. At the intersection of customization and sustainability, the Afridrille merges customer experience with genuine connection. Based on the popular espadrille style shoe, their version marries modern on-demand manufacturing technology to an artisanal production process. Customers can choose from an incredible array of styles, choosing from a range of canvas colors, printed patterns, pattern colors, and African kanga linings. There are over 23,000 different design options, so each pair represents the personality of the individual customer. That means that each pair must be made to order, not produced in bulk in advance.

The key to making this process work is technology and expertise provided by Zazzle, a Silicon Valley company that makes customizing anything a possibility. They’ve applied their cutting-edge technology to enhance the customer design process and have dedicated hundreds of hours of senior staff time to help Ubuntu develop the new product, in a collaboration that re-defines what true “corporate social responsibility” represents today.

“At Zazzle we’re thrilled to extend our platform and technologies to Makers who craft products with soul, made from the heart. And there’s perhaps no better example of this than the Ubuntu Mums,” explains Jeff Beaver, Zazzle co-founder and Chief Product Officer. “Through our partnership with Ubuntu we’ve learned that providing economic opportunity is exponentially more impactful, and sustainable, than handouts or charity. These Afridrilles are more than just awesome shoes, they are a celebration of the human spirit, and every single pair empowers these Mums, their special needs kids, and their larger community. What’s better than that?”

Crowdfunding the product launch via Kickstarter allows Ubuntu to build up production capabilities, expand the skillset of their ‘Maker Mums’, and perfect a complex operating process with the support of the Kickstarter community.

“Never underestimate the power of the entrepreneurial spirit and what can happen when people collaborate on something bigger than ourselves,” says Wilemon. “With the support of Zazzle and an eager crowdfunding audience, together we will scale up production and empower thousands of women and families in Kenya.”

At Ubuntu, empowerment means more than providing handouts or even a sustainable job. It means offering people a chance to create their own lives and livelihood. Ubuntu Made pays above-market wages to all of our employees – up to 4 times as much as they would have been able to find elsewhere in the community. We also provide health insurance to all our employees and their families, a rarity in Kenya where less than 20% have access.

The job skills our Mums learn and the money they earn empower them to buy homes – more than half of Ubuntu employees are homeowners compared to 1% nationwide. They are able to provide for their families, and sometimes start their own enterprises. They earn more than money; they earn respect in their community. Together, by providing disabled children with the healthcare and education they need, we empower them to realize their fullest potential.

That’s empowerment. That’s Ubuntu in action.

In her own words Nisha is honest, hard working and devoted. Nisha is a 28 year old mother of one. She is also a sewing machine operator at the Echotex manufacturing facility in Dhaka, Bangladesh. 6 months in into her role, the biggest challenge she’s faced is picking up the necessary skills to meet the quality standards required to produce the first NINETY PERCENT collection of premium basics. Every working morning, she says goodbye to her 5 year old son and leaves her home in Shafipur, Gazipur district to catch the rikshaw to Dhaka and make your clothes.

Greatest Achievement:

Being a kind mother to my five year old son is my greatest achievement. It’s hard to find the words to express my love for my boy but I feel heaven’s peace when he runs into my arms for a hug. It makes me so proud to see my tiny boy keep himself neat and tidy and behave well around friends and neighbours.

Work highlight so far:

Completing NINETY PERCENT collection 1 is my greatest career achievement. It was a big challenge for me to make sure the finish was first class. NINETY PERCENT is exclusive product so I had to work hard to assure the quality. I learned a lot making collection 1 and I hope these skills will serve me well in future.

Best memory:

Catching fish as a child. I fished a pond near home in my native village of Bishnupur in the Gaibandha District. The best time to fish was late autumn when the water level was down and it was easier. All the boys and girls fished together then our mothers’ cooked the fresh fish for us.

Favorite place:

Cox’s Bazar – it’s the world’s largest natural sea beach. It’s an amazing feeling by the sea with the breeze and the sand. I’ve never seen any other beaches but I’m sure Cox’s Bazar is the best. Last winter the whole family went there, all the hotels and motels there are world class for all types of foreign and local tourists.

Best life advice?

My parents advised me to always be truthful. I’ve followed this advice at every stage of my life. Wherever I have been or done I have always been truthful. Actually, I think that’s my greatest achievement. It’s advice I passed on to my child – I think that’s why he is so well behaved.

The one thing you can’t live without?

My husband is my life partner – our marriage was arranged by our families. His name is Ashraful Alam and we’ve been living for 10 years. He feels my happiness and pain and tries to help me solve problems. We have a deep understanding of each other – our eyes can read each other’s hearts. My man is wonderful. He always takes care of me and shares what he thinks.

Where do you see yourself in 5 years?

In five years time I wish to be a team-leader. First of all I want to be the best most efficient employee I can – this will see me rise. My supervisor Mr. Azizul’s motivates me and boosts my self confidence. My first day in the job was a mixture of sadness, fear and happiness. I was sad because I thought I would be busy with no more free time to do what I wish. I felt fear because I didn’t know the job or the environment. I felt happy thinking about the money I would earn. Now I wake up in the early morning to complete my family tasks then say bye to my boy and leave for work. When I’m there, I complete my tasks, then return home at 5.30 pm to focus on my family again.

When are you happiest?

I become happiest outside of work when I’m with my family. We spend our time laughing, gossiping and doing lots of things. I love to play chess with my husband and cook – especially mutton curry. Before we go to sleep we always have cup of tea together at the end of the day. Making the tea for everyone is a special moment for me.

It is with immense pleasure and utter joy that we enter our fifth year with the launch of our manifesto.

Although as a team we toyed with the idea of writing a manifesto from our very first meeting in 2013, it was forgotten at some point, overtaken by numerous other ideas generated by an overactive creative team.

It’s time for a Fashion Revolution

We always knew the importance of a manifesto for Fashion Revolution – a vehicle to share our credo, our vision of the future. But the time wasn’t right; we had to focus and push for transparency as we knew this was the first step to transforming the fashion industry. We always knew we had it in us, but somehow it was a patient impulse. Nowhere near, not yet, a guttural roar waiting to erupt.

Five years on, we have seen the effect of our #whomademyclothes campaign. We have seen how the industry can and will respond to pressure from the people who buy their clothes and how transparency has become fundamental for building trust. Now is the time for us to expand our mandate. We will continue, always, to talk about transparency, but that’s just the start of the conversation and we are ready to delve deeper.

Industries, like movements, are made of people, and people are individuals. Each one of us unique, with different tastes and different priorities, and we wanted our manifesto to reflect that. Just as the act of selecting the clothes we wear comes down to a personal choice, so too does our view of what issues are important in the supply chain.

We met in earnest as a team in the late autumn, each of us armed with our favourite manifestos from the past (the Futurist Manifesto, to Li Eldekort, the Guerrilla Girls, the Sandino Manifesto, the Storm Society) and set out to shape our own manifesto with some strong and ambitious goals.

Our name itself, Fashion Revolution, is indicative of the fact that we can’t really come up with a lacklustre set of words to encourage change. We can’t just go for a boring step-by-step “we believe” kind of approach. Revolutions come with manifestos and manifestos incite revolutions so the challenge to be provocative, poetic, inspiring, idealistic and yet focussed on creating real change was one we all relished.

We wanted a Fashion Revolution Manifesto that would be the starting point to a journey of improvement, to further understanding, and we want the people who sign it to say ‘here I am, this is my statement too. This is the journey I am sharing with others who sign this because together we make an unstoppable movement for change’. These are the principles we will take with us into the future.

Above all, we wanted a manifesto that would motivate as many people as possible: fluid and romantic, yet erudite and articulate. We wanted our tone to be tough and uncompromising, but peppered with a language that allows spontaneity and dialogue. We wanted our words to speak volumes.

This is some of the thinking we played with as we riotously sat down to write.

Revolutionary idealism is inspiring.

We need to talk about Utopia.

If everything is achievable, what happens when we have achieved it?

Abandon the past to embrace the future.

Fashion is about change / Fashion is about to change

If it’s truly revolutionary then it should be provocative to challenge the fashion industry status quo.

Belief in fashion as an empowering force

The benefits of the change we are demanding are shared by as many people as possible

And then the quiet impulse roared. It erupted like a beautiful wild beast, spontaneously and in unison. Our teamwork, yet again, provided the perfect playground for creative conception and, as we played with words and concepts, stretching through history, savouring art, being rational and irrational, we came back to earth with something that felt right.

This is our dream.

Our Manifesto is the synthesis of us; the beautiful dress we choose to wear. We want our manifesto to be inspirational and aspirational. We want to accentuate the positive, whilst simultaneously exposing its negative shadow. We have no doubt that fashion has the potential for this metamorphosis within it, and we know from our experience over the past five years that change can happen if we relentlessly speak out and call for action.

Because ultimately this is what we want to achieve, a systemic and meaningful change that is inspired by people who wear clothes, with the people who make our clothes and for the environment we all share. A manifesto that belongs to everyone, that defies elitism, and that gives us all agency.

We want millions of people to sign it.

We want your signature to be a part of a global legacy so that every time something is unjust, or people are exploited and the environment is degraded, you can reach back to it and reiterate that you can’t stand for abuse, you signed the manifesto, you are ready for change. You are ready to stand up and be counted, and the more citizens that are willing to put their signature to these principles, the more we will be able to quantify the demand for a better industry.

We are setting our vision.

We are raising our voice. We can’t know now what will change as a result, or what its effect will be, but this is our Manifesto and we pledge to always speak truth to power: this is our tool to do so. We will take it to policymakers, we will send it to brands, we will ask designers and producers to hang it in their workplace, we will use it in colleges and at events. We will share it widely on our social media and ask our friends and partners to do the same. We will not stop until we see that behaviours have changed, companies have changed, legislation has changed, fashion has changed. Unlike passing trends, this manifesto is here to stay.

Manifesto for a Fashion Revolution will lead you to an all singing, all dancing, proactive and pirouetting technicolour dream of a manifesto, with words that beg to be shouted, with statements that open your eyes in surprise and others that make you shut them to meditate further. Because we love fashion and our manifesto is also a bit of a love song.

Fashion has the potential to transform the world

Our Manifesto will bring you right into our world and show you a better future, starting now: please sign it!

On 26th April 2017, Fashion Revolution’s Head of Policy, Sarah Ditty, spoke at a high-level meeting in the European Parliament “Remembering Rana Plaza – how can we create fair and sustainable supply chains in the garment sector?”

This event came the day before an important plenary vote by Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) on a report pushing rules to curb worker exploitation throughout fashion’s global supply chains.

Good news! The European Parliament passed the resolution 505 votes against 49 with 57 abstentions. The hope is that this will lead to laws, which will ensure better working conditions for the people who make our clothes. Read the speech that Sarah gave yesterday to the European policymakers in support of the report and #whomademyclothes

“Fashion Revolution was born out of the Rana Plaza factory collapse. It started with a group of a dozen designers, academics, writers, fashion professionals and concerned citizens who felt enough is enough. A big push for system-wide change was needed more than ever.

We have since grown to become the largest fashion activism movement in the world with teams in 100 countries, including most European countries. Fashion Revolution Week is a time when hundreds of thousands of people all around the world take to social media and the streets to ask one simple question: who made my clothes? We believe this simple question gets people thinking differently about what they wear. We believe this simple question has the power to push the industry to be more transparent. If brands and retailers are encouraged to answer this question, they must take a closer look at their supply chains.

Last April our campaign reached 159 million people globally through social media and our online media reach alone in April was over 22 billion across more than a thousand articles in the press and blogs.

During this week, we also encourage producers and workers to respond with the hashtag #imadeyourclothes allowing them to stand up, be seen and celebrated, and we ask brands and retailers to respond to #whomademyclothes in order to demonstrate transparency in their supply chain. We are seeing brands increasingly getting involved.

I am here today representing the hundreds of thousands of people who participate in Fashion Revolution’s call for a safer, cleaner, fairer and more transparent apparel industry — particularly young people — of which tens of thousands of us are residents and citizens of European countries, your constituents, to tell you how much we love fashion but that we don’t want our clothes to be made off the back of exploitation, poor working conditions, unjust trade and environmental destruction. That’s a price we truly do not want to pay or worse, to inflict on others. And we believe that the government’s role — at the European level — is crucial to ensure our clothes are never made in this way.

Through our movement we celebrate fashion as a positive influence while also questioning, at times scrutinising, the industry’s practices and raising awareness of its most pressing issues.

We aim to show that change is possible and encourage those who are on a journey to create a more ethical and sustainable future for fashion. But responsible purchasing decisions are not easy to make. As consumers, we just don’t know enough about the impacts of our clothing. This needs to change.

On Monday we launched the second edition of the Fashion Transparency Index. We have reviewed and ranked 100 of the biggest global fashion brands and retailers across a variety of market segments including high street to sportswear to luxury. Brands have been ranked according to how much information they disclose about their suppliers, supply chain policies and practices, and social and environmental impact.

Brands achieved on average 49 out of 250, which is less than 20% of the total possible points. And none of the brands on the list scored above 50% — proving that there is still a long way to go towards transparency.

Overall brands are publishing the most about their policies and commitments — with 98% of the brands publishing at least some relevant social and environmental policies. However, far more space is given to brands’ values and beliefs than to their actual actions and outcomes. Brands score far fewer points when you drive further into detail about the impact of their practices on the lives of workers in their supply chains and on the environment.

The good news is that 32 of the brands are publishing supplier lists, at least at the first tier — where they have direct sourcing relationships and where garments are typically cut, sewn and trimmed. This is an increase from last year when we surveyed 40 big fashion companies and only 5 were publishing supplier lists.

In the past year we have seen brands such as ASOS, Gap, Marks & Spencer, and several others publish factory lists. This is a welcome and necessary step forward. 14 out of the 100 brands are also publishing their processing facilities where clothes are dyed, printed, laundered and otherwise finished at an earlier stage of production.

However, no brand publishes its raw material suppliers so there is no way of knowing where our cotton, wool or other fibres come from, who produces them and under what conditions. Meanwhile only 34 of the 100 brands we reviewed have made public commitments to paying living wages to workers in their supply chains, and only four brands are reporting progress against this goal — progress that has been very slow.

Finally, I would like to stress just how difficult it is to find information about brands’ supply chain and sustainability efforts. Information is often found many clicks away from the homepage of brands’ websites; or you might have to trawl through a 300+ page annual report; or you might find information using all sorts of different industry jargon and presented with an array of different visuals. No wonder consumers find it all so confusing! How are we supposed to make informed decisions about what we buy when the information is either entirely absent or presented in such varied and complicated ways?

We hope the findings of the Fashion Transparency Index encourages more consumers to ask brands #whomademyclothes pushing for more disclosure about the products we buy and wear. We hope the Index influences brands and retailers to start disclosing more information about their suppliers, practices and impacts too. We believe it will.

We hope our research facilitates the good work already being done by NGOs and unions on the ground in producing countries, equipping them with clearer data. And finally and most importantly for today’s vote, we hope that our work demonstrates to you policymakers the pressing need not only for greater transparency from the industry but that this must be underpinned by mandatory due diligence and regulations that have real teeth so that there will be a “race to the top”— and so that the brands who are trying to do the right thing no longer face a market where brands are competing on the basis of the cheapest labour costs or the cheapest materials and processes but rather on the basis of quality, design and creativity.

We, Fashion Revolution, as a voice of thousands and thousands of everyday concerned European citizens and consumers, ask you to vote in favour of the report tomorrow. We hope this is the first step towards a fashion industry in Europe that values people, planet and profit equally.”

What the lives of garment workers can teach multi-national brands and their customers

Fatima, Sokhaeng, and Usha are all garment workers making clothes for multi-national brands in factories across South and Southeast Asia. Fatima lives and works in Dhaka, Sokhaeng in Phnom Penh, and Usha in Bangalore. Their work is similar—cutting and sewing garments for eight or more hours per day, but their lives and the lives of their compatriots also vary in important ways. What can the lives of these women teach multi-national brands and their customers about how to create and maintain sustainable supply-chains, where people who make the clothes that the world wears are treated with respect and do more than just survive? In other words, how can brands, with the support of consumers, win the “race to the top” where all do well, rather than the proverbial “race to the bottom” where brands compete by getting as much out of their workers for as little as possible?

Fatima, Sokhaeng, and Usha are three of 540 women that Microfinance Opportunities has been tracking for the last eight months or so. We have been asking them about how they earn and spend their money, their daily schedules, whether they are happy, in pain, or suffered an injury, the conditions in their workplace, and any special events that happened in their lives. From this information we have been able to weave together the individual stories of the workers, as well as generate an aggregate picture of the lives of the women who make our clothes. You can find accounts of these stories here for Bangladesh, Cambodia, and India.

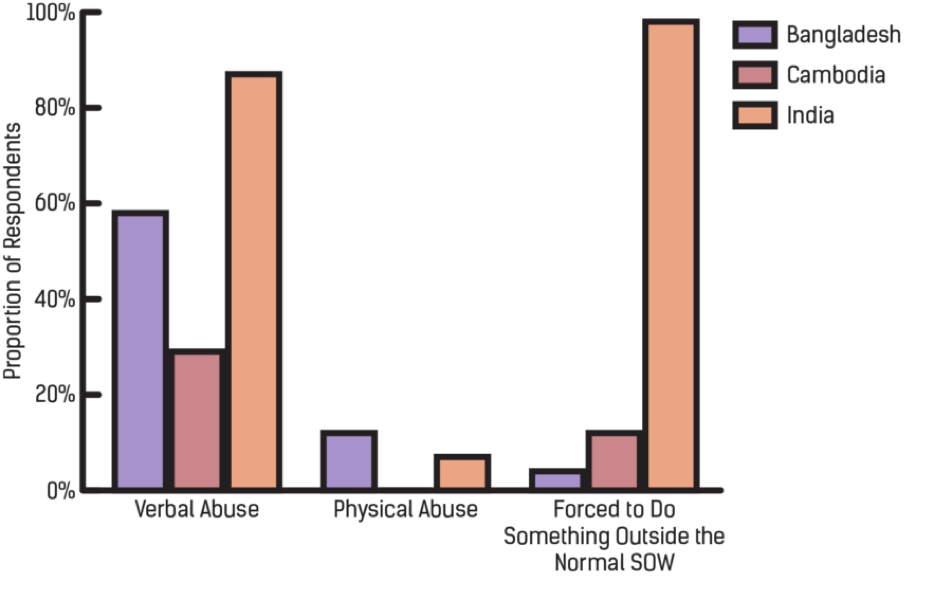

Fatima and others like her who are participating in the Garment Worker Diaries in Bangladesh often worked over 60 hours a week in the latter part of 2016 during the first few months of the study. In contrast, Usha and the other workers in Bangalore invariably worked 48 hours a week or less—still a lot but far less than the women in Bangladesh. The women in Cambodia fell somewhere in between—48- to 60-hour weeks were the most common in Cambodia. Furthermore, in both Bangladesh and Cambodia, the number of hours the women worked per week varied far more than they did in India, where the women consistently reported 48-hour weeks.

Figure 1: Hours Worked per Week

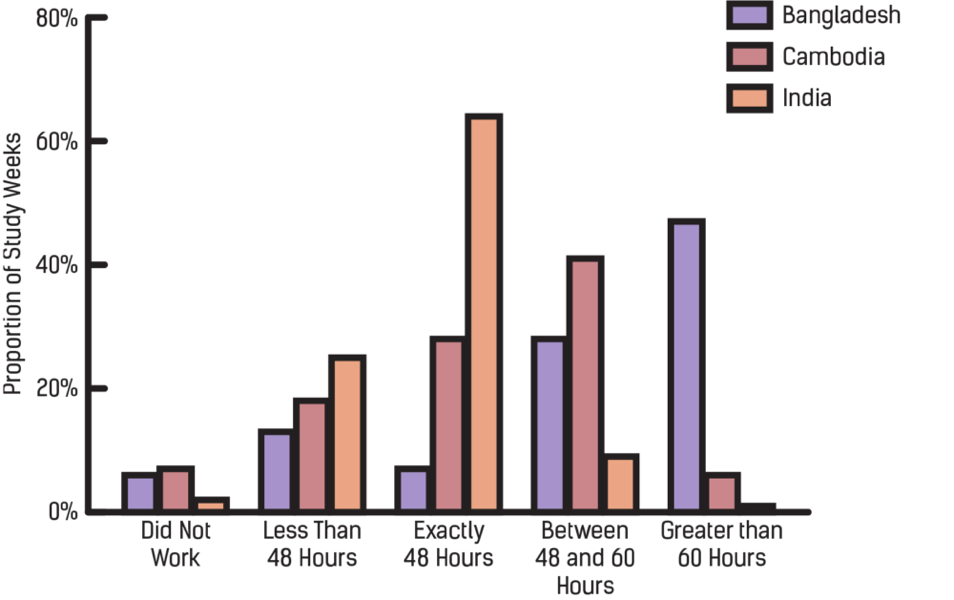

From the reports of how many hours they worked and how they varied from week to week, it looks like the women in India are the best off. But this is not altogether the case. Usha and her Indian counterparts reported far higher levels of verbal abuse in the workplace than did the women in Dhaka or Phnom Penh. And women in India consistently reported being forced to do more work than their allotted quota for the day. Meanwhile, women in Cambodia had the fewest reports of verbal abuse and no reports of physical abuse.

Figure 2: Reports of Abuse at Work

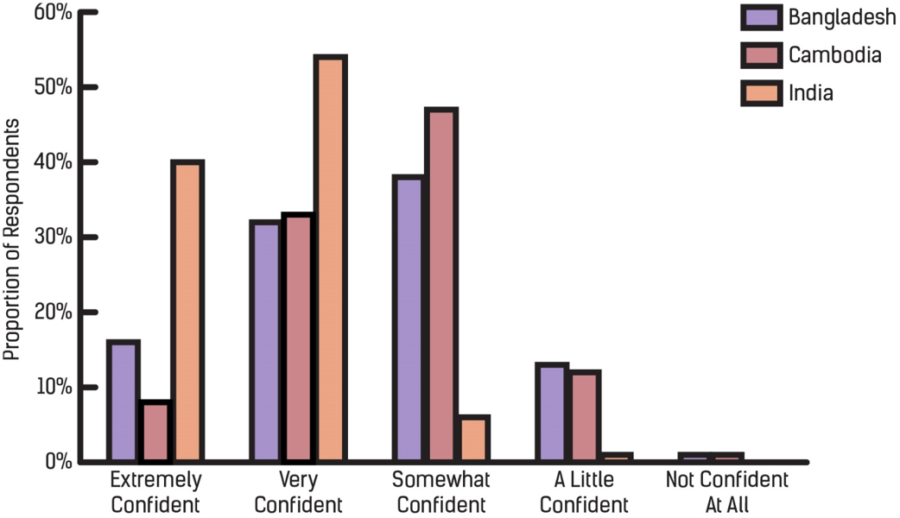

Further complicating the picture, women in Bangladesh and Cambodia participating in the Diaries study reported having mixed levels of confidence in whether they would be able to use the emergency exits in their workplaces in case of an emergency—almost 40 percent of Bangladeshi and 50 percent of Cambodian workers were only somewhat confident, while the Indian women reported the most confidence—over 90 percent reported they were extremely or very confident.

Figure 3: Confidence in Use of Emergency Exits

There may, of course, be differences across the countries in how the women perceive their situation, but even taking this possibility into account the differences across countries are so great that it is hard to fathom that they are simply due to differences in perception. What these findings suggest is that just because a set of factories in one country have worse conditions than factories in another country on one dimension does not mean that they have the worse conditions on all dimensions. So why can’t factories in Bangladesh and Cambodia and the brands that hire them have their workers work reasonable hours? Why can’t Indian factories stop the verbal abuse their workers suffer? Why can’t the Bangladeshi and Cambodian factories ensure that their workers can use designated exits in an emergency?

From a human rights perspective we can simply argue that the factories and the brands that hire them should stop treating their workers badly and adhere to some basic standards—higher than the best experiences of the women in our study. But these findings suggest that even by the lower standards of “business necessity” there is no justification for the behavior of the factory managers and the brands that hire them: other factories are able to treat their workers better in certain ways and stay in business, so why shouldn’t all factories be able to do so? In other words, there is no excuse for the treatment of the workers that the Diaries data are revealing, even by the lower standard of “we have to treat our workers this way just to stay in business.” It is time that the brands send this message loud and clear to factory managers, and that consumers ask the same of the brands. This way, maybe we can see the beginnings of a “race to the top.”

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Garment workers in Phnom Penh often live in housing blocks like the ones seen here—single rooms in dystopian looking concrete buildings. While the homes often have electricity and private bathrooms, there are many in less-developed areas of the city like these, which are located next to an informal trash dump. On average, a room in one of these buildings will cost 120,000 riels per month, equal to about $30.

Workers leave their homes early in the morning to walk to their factories. The factories vary in size and formality but they are often in walled compounds with large metal gates. Conditions in factories have improved over the years but many of our respondents report that they are concerned for their safety for various reasons.

Workers typically get a quick break for lunch and crowds of women will surround vendors like this one, snatching up her prepared lunch fare for a few thousand riels. Workers will also sometimes buy prepared breakfasts and dinners from vendors too.

After their shifts, which can last anywhere from eight to 12 hours, garment workers leave their factories and walk home. The women in the photo wear hats and long sleeves shirts to protect themselves for the sun. Some wear scarves or facemasks, which they use to try to limit dust and chemical smells they breathe in while working.

The women in our study will often purchase food for dinner on the way home from the factory. They do this almost every day—food will spoil if kept too long and most homes do not have refrigerators. The markets of Phnom Penh are loaded with fish, snails, chicken, and beef as well as fruits and vegetables. While many respondents cook using gas stoves, fish is best cooked over coals.

Long days at the factory followed by chores around the home tire our garment workers. The women in our study like to relax at the end of the day, if they have the time, and many enjoy watching television. However, many cannot watch for much longer than an hour—they have to sleep so that they are rested for another day of sewing clothes destined for Western markets.

Kampong Speu, Cambodia

Most garment factories in Cambodia are in Phnom Penh but they are also located in other provinces of Cambodia, including Kampong Speu. Life here is much different from life in Phnom Penh. Homes here are larger and similar in style to the home above.

Garment work is an important source of employment for young women living in this area but households often engage in other livelihoods too. For example, many households engage in some type of agriculture.

Buddhism is the national religion of Cambodia and evidence of its influence is visible throughout the country. One key example—many communities have a Buddhist temple similar to this one. It is a place for meditation and learning. Our respondents in Kampong Speu sometimes bring offerings to temples during religious holidays.

Religious and traditional beliefs are prevalent in this area. Figures, like the one shown here, guard homes from evil spirits. People hope that the figures will keep things like illnesses or curses into the home.

Bangalore, India

Our respondents in Bangalore live in a variety of types of homes. Some live in in single-family, detached homes like those in this community near the town of Mandya.

Others live in apartment buildings of various shapes and size. These apartments are located near the town of Bidadi, less than an hour away from Bangalore by car. The unpaved roads and construction show that this area is still developing.

Regardless of where respondents live, they are all bound by a schedule set by the factories. Each morning, the garment workers wake-up early to prepare themselves and their families for the day. They will often take a factory-sponsored transport to their jobs where they will work for eight hours.

After their shifts, the women stream out of their factories and board transports headed back to their homes. Some work conditions here are better than in the other countries we are studying, but the women in our sample report that their supervisors yell at them frequently.

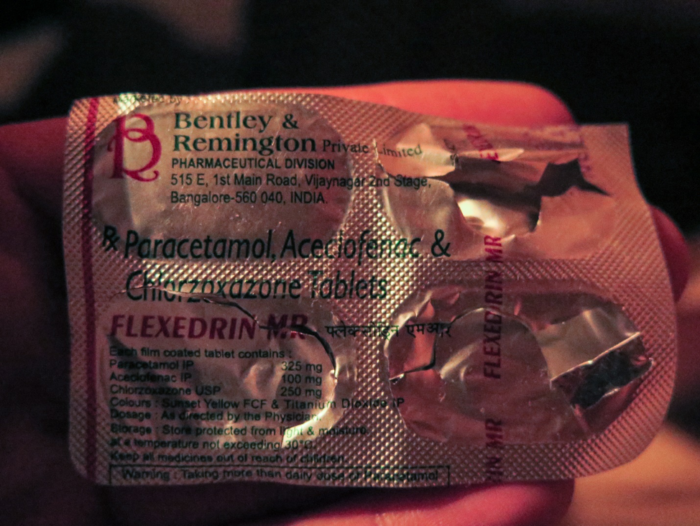

While the workers here often have shorter days than those in Bangladesh and Cambodia, the repetitive nature of their tasks takes its toll. Many workers complain of pain in the arms, back, and legs. One worker we visited had gone to the clinic and a doctor prescribed these painkillers.

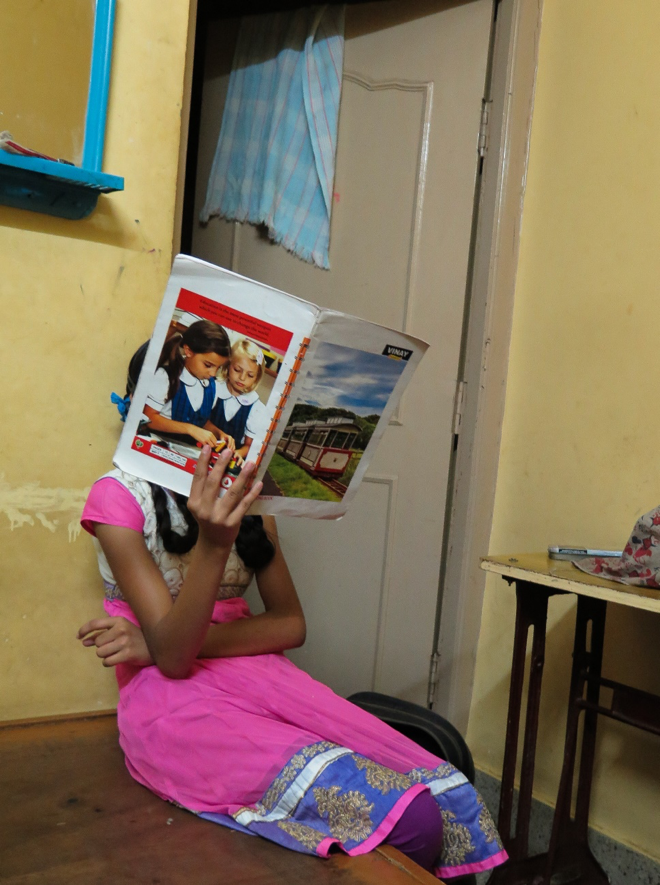

The women in our sample often do not get much leisure time—they have to cook and clean for their families and care for their children. In this photo, the daughter of one of our respondents studies. Outside the frame, her mother is keeping a watchful eye even as she conducts an interview with one of our enumerators.

Many of the respondents in our sample are Hindu and devout followers often have some kind of shrine in their homes. Images of gods, oil candles, and decorative flowers are common. At the end of a long day, some workers will say a quick prayer before beginning their routine again the next day.

Usha is a 32-year-old mother and a nine-year veteran of India’s garment industry. Compared to garment workers in Bangladesh, Cambodia, and workers within neighboring states in India, Usha is well-off.

She works an average of eight hours per day, six days per week in a factory on the outskirts of the city of Bangalore. She lives nearby in the village of Bidadi with her two daughters, son, and husband in a well-appointed home. Unlike some workers who only perform one task every day, Usha gets to perform many because her supervisors consider her one of the most experienced workers in the factory. Furthermore, her factory is relatively safe, with an on-site clinic and clearly marked exits.

But this is not Usha’s whole story. Weekly data collected from the Garment Worker Diaries show that Usha and women like her face meaningful issues in the workplace. Hardships include verbal and physical abuse and little room for career advancement. Even with variety in her work, she labors over a sewing machine each day, which is causing her chronic back pain. She has little hope of improving her station. Usha’s supervisors have told her repeatedly that a woman such as her, with so little education, cannot hope to be promoted.

The injustices do not stop on the factory floor. Usha has faced the consequences of India’s demonetization campaign, struggles to pay school fees for her children, and has a meaningful portion of her salary deducted to pay for social services that she struggles to use.

Thus, while Usha lives well in comparison to many garment workers, she still faces meaningful injustices. Without the chance to demand improvements in her station, is Usha facing the idiomatic “death by a thousand cuts”?

Read our full report, “A Thousand Cuts: Life as a Garment Worker in Bangalore.”

Read the summary (2 page pdf)

While this is the last country-specific interim report of this project, stay tuned as MFO and Fashion Revolution will be sharing photo essays and blogs and hosting a Twitter hour as part of Fashion Revolution week beginning April 24, 2017. Stay up-to-date with our Garment Worker Diaries project along the way. If you are interested in discussing any of our findings or have any questions for our researchers, please feel free to contact us at enquiries@mfopps.org.

A thin, grey mist spreads throughout the morning air in Akran, a small neighborhood in the manufacturing suburb of Savar, just outside of the city of Dhaka.

It winds its way through the streets, climbing buildings, depositing tiny dewdrops on windows, leaving faint wet splotches on the awnings that cover nearby market stalls. The mist presses onward to the outskirts of town until it reaches a residential area full of large, single-story stone dwellings.

These dwellings, divided into many separate units, hold small communities of Bangladeshi families. As the mist disperses and the morning’s sunbeams reach the homes, the inhabitants stir. They awaken and begin their morning routines: adults wash and dress themselves, cooking breakfast as the children prepare themselves for school. After their morning rituals, adults and older children make their way to agricultural fields, brick factories, and local bazars to try to earn a living, while multitudes of other workers, like Fatema and Halima, make their way to nearby garment factories.

Fatema and Halima politely greet each other on the main road to the Samair neighborhood, about a 30-minute walk away, where both women work at the same factory. After exchanging pleasantries, they begin their trek to their workplace, merging into crowds of workers as they walk towards the factory gates.

Fatema and Halima are two of the roughly four million garment workers employed in the ready-made garment (RMG) sector, Bangladesh’s largest export industry. They are also two of the 182 Bangladeshi women who have volunteered to participate in the Garment Worker Diaries, a yearlong project capturing data on the lives of garment workers.

Each week, a team of field researchers from BRAC—a development organization dedicated to empowering people living in poverty and the world’s large non- government organization—visits participating workers to ask detailed questions about their earnings and expenditures, working conditions, daily schedule, physical well- being, and major events that happened in their lives. Analyzing the data across weeks allows us to connect seemingly unrelated events to develop a holistic understanding of the economic realities that participants face.

Download and read the below report to find out how Fatema and Halima’s stories unfold against the backdrop of a society with slowly changing gender relations and an apparel industry that is sluggishly improving working conditions and pay.

Read the full report (pdf)

Read the summary (2 page pdf)

It is the first Saturday of July 2016, and the streets of Phnom Penh’s Meanchey district—an area concentrated with garment factories—are relatively calm.

It is late morning, and food vendors are preparing for the busiest time of the day: lunch. They put small helpings of rice, vegetables, and fish into little plastic bags, hastily organizing their offerings on top of their pushcarts for easy perusal. Their work is rhythmic: pack, tie, and place, pack, tie, and place. In front of them, motorbikes weave past each other, a scene of organized chaos with the mid-pitch hum of tiny engines as the soundtrack.

By noon, dozens of the factories that dot this area have opened their doors and thousands of garment workers are filling the streets. Girls and women pull off headscarves and facemasks even as the marching crowd kicks dust into the air. The market turns into a feeding frenzy as workers hastily snatch up bagged lunches for a couple thousand riels.* Some go back to the factory grounds to eat and rest. Others find informal bars and restaurants and watch TV. Pregnant workers stretch gingerly. Within the hour, they will all be back at their stations, cutting and sewing garments for a range of multi-national brands.

Sokhaeng’s story

Somewhere in the crowd, Sokhaeng stands near a vendor, debating between fish with a mango relish or rice and vegetables for her lunch. She will make her purchase and return to the sea of workers flowing in and out of factory gates.

Sokhaeng is one of the thousands of women who sit at a sewing machine for hours, turning pieces of cloth into garments destined for Western markets. She is also one of 187 women in Cambodia participating in the Garment Worker Diaries, a yearlong project capturing data on the lives of garment workers.

Sokhaeng’s story, which includes data from the first week in July 2016 to the second week in November 2016, is relevant because the data so far suggest that it is indicative of the experience of our sample of garment workers. She lives in a home that is typical for garment workers in Phnom Penh and has similar demographic and economic characteristics. Her experience in her factory is characteristic of those of the other women we interviewed and her day-to-day activities are reflective of the rhythms of these women’s lives. In other words, Sokhaeng’s story illuminates the experience of garment workers in our study generally.

To find out what Sokhaeng has done to scrape by on the low pay she receives as a garment worker, read the report below. Will she be able to afford her dream of becoming a beautician and provide for her family’s basic needs at the same time?

Read her story (pdf)

Read the summary (2 page pdf)

*On April 3, 2017, one U.S. dollar equated to roughly 4,000 Cambodian riels; one British Pound equated to roughly 5,000 Cambodian riels; and one Euro equated to roughly 4,300 Cambodian riels.”

Strikes, Rents, and Wages

During the last two weeks of 2016, as consumers in the United States and Europe were donning their new holiday outfits, the garment workers who made those clothes in the manufacturing hub of Ashulia in Bangladesh were being arrested by police, and factory owners sacked workers by the thousands.

The heavy-handed actions were a response to workers’ protests against high rents and low wages. Garments workers said they could not pay rent and purchase daily necessities like food, basic clothing, and medicine on the paltry minimum wage of $68 a month. In response, the Government of Bangladesh’s Minister of Commerce Tofael Ahmed announced that the government would ensure that rents in the Ashulia area would not increase for three years.

Unfortunately, new data from Microfinance Opportunities’ Garment Worker Diaries shows that current rent levels are driving garment workers to accumulate debt in order to provide basic necessities for themselves and their families. Consequently, the government’s promise to hold rents steady is unlikely to provide workers with financial relief.

Debt for the Renters

We are currently conducting weekly interviews with 181 female garment workers who live in manufacturing hubs throughout Bangladesh, including 16 who live in Ashulia. Two-thirds of the sample are responsible for paying their household’s rent. Women who do and do not pay rent share many similarities. The majority of the women are married, and they have comparable education levels and positions in their factories, although those who pay rent are slightly older. The women that are married live with their husbands and children in one room with no bathroom or formal cooking area; those that are not share similar spaces with other family members or other garment workers.

The economic behavior of these two groups is as different as their demographic characteristics are the same. The data make clear that rent is a huge burden for the two-thirds of women who pay it, demanding 40 percent of the value of a monthly paycheck on average. These women purchase goods on store credit more than twice as often as the women who do not pay rent, borrowing goods each month with a value equivalent to almost 20 percent of an average paycheck. The goods they purchase are not luxuries – they borrow basics like food, soap, and medicine for themselves and their families.

Women who pay rent use more cash loans too – they receive cash loans once every two months on average compared to once every four months for those who do not pay rent. Women who pay rent borrow loans that are almost three times the size of the ones that other garment workers borrow. At $37, these loans are roughly equivalent to our garment workers’ monthly rent.

Debt, In Cycles

Women do not acquire this debt haphazardly or in response to unusual events – their behavior is cyclical. In the weeks between monthly paychecks, women borrow goods from store vendors and take cash loans, using the cash to purchase basic goods they cannot get on credit and to pay rent for the upcoming month.

Their paychecks make them flush with cash but only for a moment – in addition to rent, they have to repay their outstanding loans from the previous month. After paying their rent and these loans, they are short on cash, and the cycle of taking on and repaying debt begins again.

Holding Rents: Nothing More Than a Platitude

This cycle has the makings of a catastrophe. An unexpected event, like a medical emergency, could be devastating for women already living on the financial edge. Women who lose their factory jobs may be unable to repay their debts, forcing them to borrow from riskier sources, and pushing them deeper into a debt trap.

From this perspective, the Government of Bangladesh’s promise to hold rents steady is nothing more than a platitude, a promise that while garment workers’ rent-induced stress may not increase, it will not be relieved in the near future. Instead, the workers will continue to exist in a status quo defined by the pressure of borrowing to make ends’ meet and working 60 hour weeks to ensure debts can be paid.

by Eric Noggle

The Garment Worker Diaries is a yearlong research project that is collecting data on the lives of garment workers in Bangladesh, Cambodia, and India. Microfinance Opportunities is leading the project with support from C&A Foundation. Fashion Revolution will use the findings from this project to advocate for changes in consumer and corporate behavior and policy changes that improve the living and working conditions of garment workers everywhere.

Follow the yearlong study on social media #workerdiaries

Los Diarios de los Trabajadores de la Confección es un proyecto de investigación de un año de duración liderado por Microfinance Opportunities en colaboración con Fashion Revolution y con el apoyo de C&A Foundation. Estamos recopilando datos sobre la vida de trabajadores de la confección en Bangladesh, Camboya e India. Fashion Revolution utilizará las conclusiones de este proyecto para abogar por cambios en el comportamiento de los consumidores y las empresas y por cambios de política que mejoren las condiciones de vida y de trabajo de los trabajadores de la confección en todo el mundo.

Docenas de fábricas de ropa de color beige se alinean en las calles de las afueras de Phnom Penh. Los complejos están protegidos por muros de más de 3 metros de altura, puertas metálicas y controles de seguridad en las entradas. Por la mañana temprano, los trabajadores de la confección que viven cerca salen de su casa – a menudo una habitación de 6,5 metro cuadrados con baño compartido – y entran en estas fábricas, contándose por miles los que comienzan su jornada de trabajo. Durante las siguientes ocho a 12 horas, cortan y cosen prendas para las grandes marcas de ropa, quienes le venden los productos terminados a personas como usted y a miles de millones más en todo el mundo. Cuando los trabajadores salen, muchos se quejan de dolores de cabeza y dolor crónico en brazos y espalda, agravados por los movimientos repetitivos de su trabajo. Realizan esta rutina seis días a la semana, y por su trabajo, el gobierno de Camboya ordena que los propietarios de las fábricas les paguen un mínimo de 140$ al mes, o setenta centavos la hora basándose en una semana laboral de 50 horas. Las situaciones en Bangladesh y la India son similares. Cientos de miles de trabajadores trabajan largas horas con la esperanza de recibir el salario mínimo, que está fijado en 68$ y 105$ al mes, respectivamente.

Los defensores de los derechos laborales dicen que los trabajadores a menudo reciben menos del salario mínimo en Bangladesh, Camboya e India. Incluso si reciben el salario mínimo, dicen los defensores, puede que no sea suficiente para los trabajadores que necesitan pagar los gastos de vivienda y proveer de alimentos, atención médica y otras necesidades a sí mismos y a sus familias.

Si su salario no puede cubrir sus necesidades, ¿cómo sobreviven? ¿De dónde sacan el dinero para cubrir los gastos básicos? ¿Eligen entre enviar dinero a sus familias en las aldeas rurales o comprar la comida suficiente para alimentarse durante la semana?

¿Qué pasa detrás de esas grandes puertas metálicas? ¿Sus supervisores les animan o les amonestan cuando hay una orden importante de ropa? ¿Con qué frecuencia experimentan dolor crónico a causa de su trabajo? ¿Qué hacen cuando se lesionan?

Estamos supervisando a investigadores de campo que están haciendo estas preguntas a 180 trabajadores de la confección por país en Bangladesh, Camboya e India. Durante los próximos 12 meses, los entrevistadores visitarán al mismo grupo de trabajadores de la confección semanalmente para conocer los detalles íntimos de sus vidas. Preguntarán a los trabajadores de la confección sobre lo que ganan y compran, cómo invierten su tiempo a diario, y si experimentan algún tipo de acoso, lesiones o dolencias mientras están en la fábrica. Los entrevistadores aprenderán también sobre eventos importantes que ocurran en las vidas de los trabajadores, desde fiestas de cumpleaños y bodas hasta enfermedades y funerales de familiares y amigos.

Estos datos son un tesoro: imagina lo que aprenderías sobre una persona haciendo preguntas detalladas sobre su vida semanalmente, cada semana durante un año entero. Nuestro trabajo como investigadores es analizarlo objetivamente y proporcionar respuestas a las preguntas de lo que sucede detrás de las puertas de esas fábricas y, lo que es más importante aún, lo que sucede después, cuando salen los trabajadores.

Nuestra esperanza es que las empresas de ropa, los consumidores, los dueños de fábricas y los encargados de formular las políticas puedan utilizar las ideas que identificamos para entender cómo afectan las decisiones que toman a la situación de los trabajadores de la confección. Para ello, estamos trabajando con Fashion Revolution para poner nuestros datos a disposición de los responsables del cambio quienes pueden influir en la cadena de suministro de ropa global, el marco normativo y las protecciones sociales disponibles para los trabajadores de la confección.

Uno de los agentes más importantes del cambio es usted: consumidor, impulsor de tendencias y comprador de ropa. A lo largo de los próximos meses, Fashion Revolution y nuestro equipo compartirán los hallazgos de nuestro proyecto a través de medios sociales, blogs, fanzines, informes y exposiciones. Le animamos a mantenerse informado de nuestro trabajo para así también poder defender a las personas que hicieron su ropa.

Autores: Eric Noggle y Guy Stuart, Microfinance Opportunities

C&A Foundation está proporcionando apoyo financiero para Los Diarios de Trabajadores de la Confección. Estamos colaborando con Fashion Revolution para distribuir los resultados. Nuestros socios locales son BRAC (Bangladesh), TNS (Camboya) y Morsel Ltd. (India).

Phann is a 40-year-old garment worker living in Phnom Penh with her husband, a security guard. Their rented room is typical for a garment worker—encased by concrete walls and covered by a tin roof with one bathroom and no kitchen. Since Microfinance Opportunities (MFO) began interviewing her in July, Phann has reported working long hours, making products for major clothing brands. She has worked 61 hours a week on average, including three weeks when she worked more than 70 hours, well above the 60-hour week maximum mandated by Cambodian law. Despite her illegal hours, she is paid 66 cents an hour according to our data, falling just short of the legal minimum wage of 67 cents per hour.

Phann, like the other 180 women participating in MFO’s Garment Worker Diaries in Cambodia, is hoping that 2017 will bring new money as the Government of Cambodia has mandated that factory owners increase the minimum wage from 67 cents to 73 cents per hour, equivalent to an increase from $140 to $153 per month [1].

Most of our diarists are positioned to receive that increase—approximately 68 percent report earning the minimum wage, if not higher. The other 32 percent of workers stand to be disappointed, according to a preliminary analysis of the data. They earn only 57 cents an hour on average, so far below the minimum wage that an almost 30 percent increase in their wages is unlikely.

Not only are they receiving less than the minimum wage, but the ways in which their earnings are calculated are often opaque, and their payment schedules are inconsistent. For instance, Mao—a 28-year-old garment worker living in Phnom Penh—received checks showing that she earned the minimum wage. During our first interview, she reported that the factory paid her $140, but she could not tell us how many hours she worked during the pay period. At that moment, we were hopeful she would be one of the garment workers who received fair wages for her work. Her next check was for $137.50, but she worked 250 hours during the pay period which equates to only 55 cents an hour. She fared better on her next paycheck, earning 68 cents an hour for 227 hours of work. However, by the time she received her fourth check, any pretense that she was receiving fair wages had disappeared. She earned $90 for 200 hours of labor, equal to 45 cents an hour.

At least Mao’s employer paid her. Chen, who works in another factory in Phnom Penh, worked 194 hours but was never paid as her employer absconded. She and her colleagues did everything possible to stop him: they attempted to block the exits to the factory to prevent his escape and sought a court order to detain him, or at least seize the assets of the factory, but those efforts proved unsuccessful. As of this writing, she has still not received any compensation for her work.

For women like Mao and Chen, and women like Phann who are paid fairly but work in excess of what is allowed by law, an increase in the minimum wage will not be enough to ensure their dignity. Brands and the Government of Cambodia must enforce the regulations that ensure fair wages and working conditions.

There has been slow progress in this regard, and a lack of transparency in the supply-chain makes evaluating the pace of progress difficult. Organizations like the Solidarity Center and Human Rights Watch are investigating working conditions to bring better transparency to the sector, but their main leverage point is to indict the reputation of the brands, a real but indirect threat to brands’ bottom lines. Consumers, with their ability to directly impact brands’ by altering their purchasing patterns, are the ultimate leverage point. For change to occur, you as consumers must demand transparency and fairness throughout the supply-chain.

To ensure dignity for these women, you must demand a fashion revolution.

[1] The legal minimum wage in Cambodia is $140 per month and is not typically reported as an hourly rate. The legal regular work week, before earning overtime, is 48 hours per week. For an average month, this equates to 67 cents per hour. The government has set the minimum wage in 2017 at $153, equal to 73 cents per hour.

The Garment Worker Diaries is a yearlong research project, led by MFO and supported by C&A Foundation, which is collecting data on the lives of garment workers in Bangladesh, Cambodia, and India. Fashion Revolution will use the findings from this project to advocate for changes in consumer and corporate behavior and policy changes that improve the living and working conditions of garment workers everywhere.