A Race to the Top

What the lives of garment workers can teach multi-national brands and their customers

Fatima, Sokhaeng, and Usha are all garment workers making clothes for multi-national brands in factories across South and Southeast Asia. Fatima lives and works in Dhaka, Sokhaeng in Phnom Penh, and Usha in Bangalore. Their work is similar—cutting and sewing garments for eight or more hours per day, but their lives and the lives of their compatriots also vary in important ways. What can the lives of these women teach multi-national brands and their customers about how to create and maintain sustainable supply-chains, where people who make the clothes that the world wears are treated with respect and do more than just survive? In other words, how can brands, with the support of consumers, win the “race to the top” where all do well, rather than the proverbial “race to the bottom” where brands compete by getting as much out of their workers for as little as possible?

Fatima, Sokhaeng, and Usha are three of 540 women that Microfinance Opportunities has been tracking for the last eight months or so. We have been asking them about how they earn and spend their money, their daily schedules, whether they are happy, in pain, or suffered an injury, the conditions in their workplace, and any special events that happened in their lives. From this information we have been able to weave together the individual stories of the workers, as well as generate an aggregate picture of the lives of the women who make our clothes. You can find accounts of these stories here for Bangladesh, Cambodia, and India.

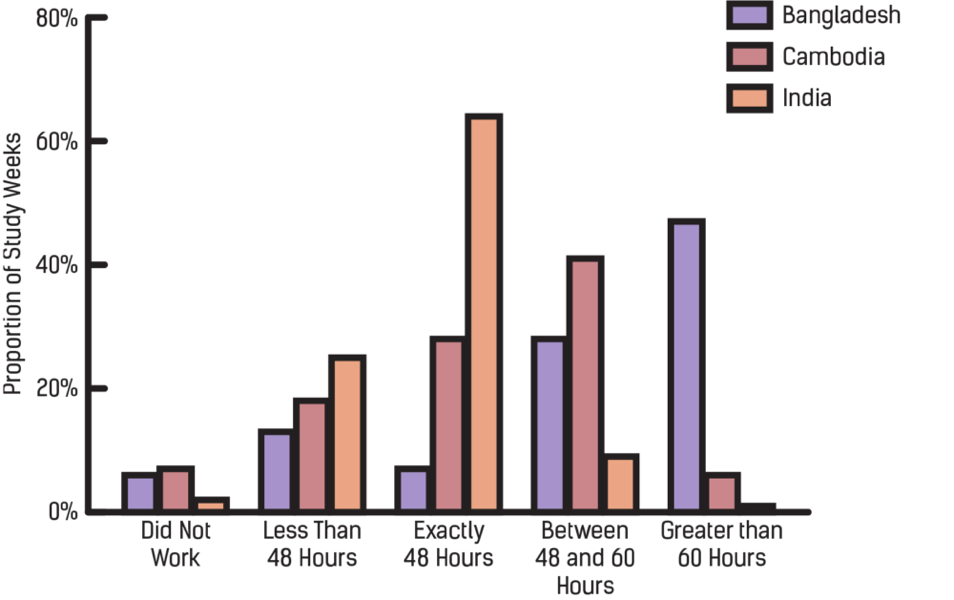

Fatima and others like her who are participating in the Garment Worker Diaries in Bangladesh often worked over 60 hours a week in the latter part of 2016 during the first few months of the study. In contrast, Usha and the other workers in Bangalore invariably worked 48 hours a week or less—still a lot but far less than the women in Bangladesh. The women in Cambodia fell somewhere in between—48- to 60-hour weeks were the most common in Cambodia. Furthermore, in both Bangladesh and Cambodia, the number of hours the women worked per week varied far more than they did in India, where the women consistently reported 48-hour weeks.

Figure 1: Hours Worked per Week

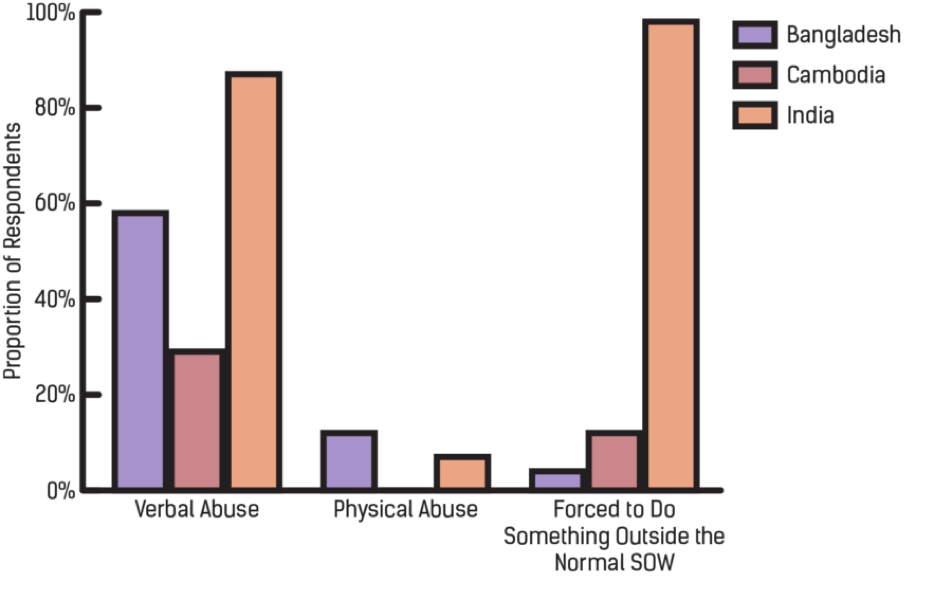

From the reports of how many hours they worked and how they varied from week to week, it looks like the women in India are the best off. But this is not altogether the case. Usha and her Indian counterparts reported far higher levels of verbal abuse in the workplace than did the women in Dhaka or Phnom Penh. And women in India consistently reported being forced to do more work than their allotted quota for the day. Meanwhile, women in Cambodia had the fewest reports of verbal abuse and no reports of physical abuse.

Figure 2: Reports of Abuse at Work

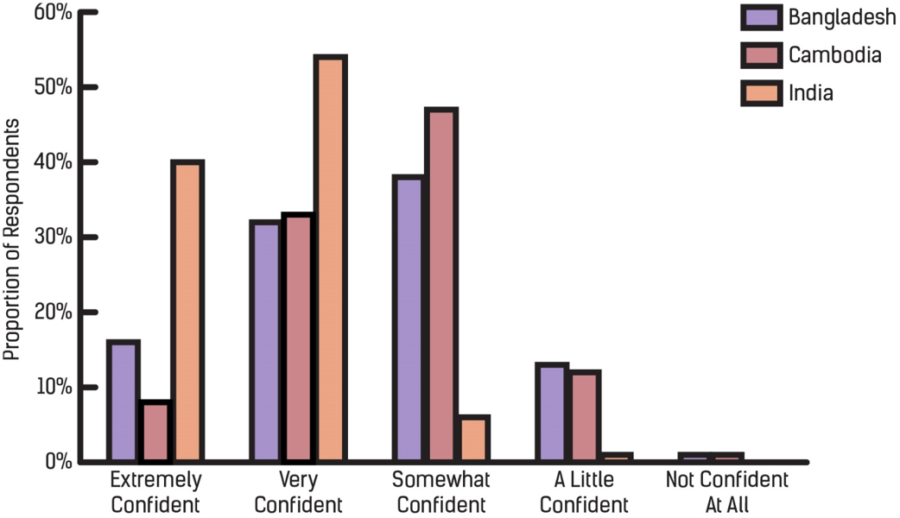

Further complicating the picture, women in Bangladesh and Cambodia participating in the Diaries study reported having mixed levels of confidence in whether they would be able to use the emergency exits in their workplaces in case of an emergency—almost 40 percent of Bangladeshi and 50 percent of Cambodian workers were only somewhat confident, while the Indian women reported the most confidence—over 90 percent reported they were extremely or very confident.

Figure 3: Confidence in Use of Emergency Exits

There may, of course, be differences across the countries in how the women perceive their situation, but even taking this possibility into account the differences across countries are so great that it is hard to fathom that they are simply due to differences in perception. What these findings suggest is that just because a set of factories in one country have worse conditions than factories in another country on one dimension does not mean that they have the worse conditions on all dimensions. So why can’t factories in Bangladesh and Cambodia and the brands that hire them have their workers work reasonable hours? Why can’t Indian factories stop the verbal abuse their workers suffer? Why can’t the Bangladeshi and Cambodian factories ensure that their workers can use designated exits in an emergency?

From a human rights perspective we can simply argue that the factories and the brands that hire them should stop treating their workers badly and adhere to some basic standards—higher than the best experiences of the women in our study. But these findings suggest that even by the lower standards of “business necessity” there is no justification for the behavior of the factory managers and the brands that hire them: other factories are able to treat their workers better in certain ways and stay in business, so why shouldn’t all factories be able to do so? In other words, there is no excuse for the treatment of the workers that the Diaries data are revealing, even by the lower standard of “we have to treat our workers this way just to stay in business.” It is time that the brands send this message loud and clear to factory managers, and that consumers ask the same of the brands. This way, maybe we can see the beginnings of a “race to the top.”