“My particular bugbear is feminist tees which were not made by women who were paid fairly for their labour. Check your tags and brands” posted actress Aisling Bea during Fashion Revolution Week.

Slogan T-shirts with female empowerment messages are everywhere now, from the We Should All be Feminists T-Shirt on the catwalk at Christian Dior to the myriad versions sold in the High Street to coincide with International Women’s Day, but the reality is that the fashion industry doesn’t empower the majority of women who work in it. Gender-based inequality remains a problem throughout the industry, from the highest levels of management to the shop floor and the factory floor.

When I met with the President of the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association in November, he told me that sexual harassment doesn’t exist in garment factories in Bangladesh, whereas statistics show around 60% of Bangladeshi garment workers have suffered from sexual harassment. Earlier this week, Fashion Revolution organised Fashion Question Time at the Houses of Parliament, hosted by Mary Creagh MP. The panellists debated whether, 5 years after the Rana Plaza disaster, the fashion industry was a better place for women to work. I put forward the question ‘The #MeToo movement is inspiring, but can it ever deliver freedom from discrimination and abuse for the millions of women who work in fashion supply chains?’

Lord Bates responded “there are two things that always work to lift people out of poverty: education for women and girls and female economic empowerment”.

Rushanara Ali MP added “we need to focus on the rights agenda as much as we do on economic empowerment to get results. We need to target our DFID aid efforts to this as mch as social and economic development. We have a female Prime Minister and I’d like to see us use our leadership globally”.

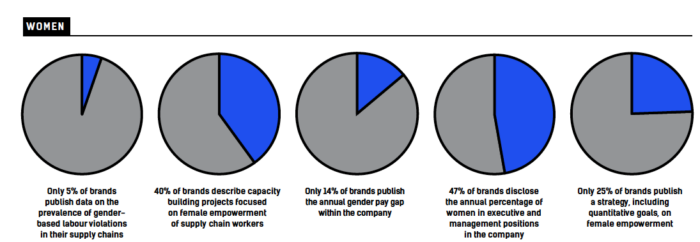

Research published this week by Fashion Revolution shows that gender-based inequality remains a problem throughout the fashion industry, from the highest levels of management to the shop floor and the factory floor. About 75 million people work directly in the fashion and textiles industry and about 80% of them are women. Many are subject to exploitation and verbal and physical abuse. They are often working in unsafe conditions, with very little pay.

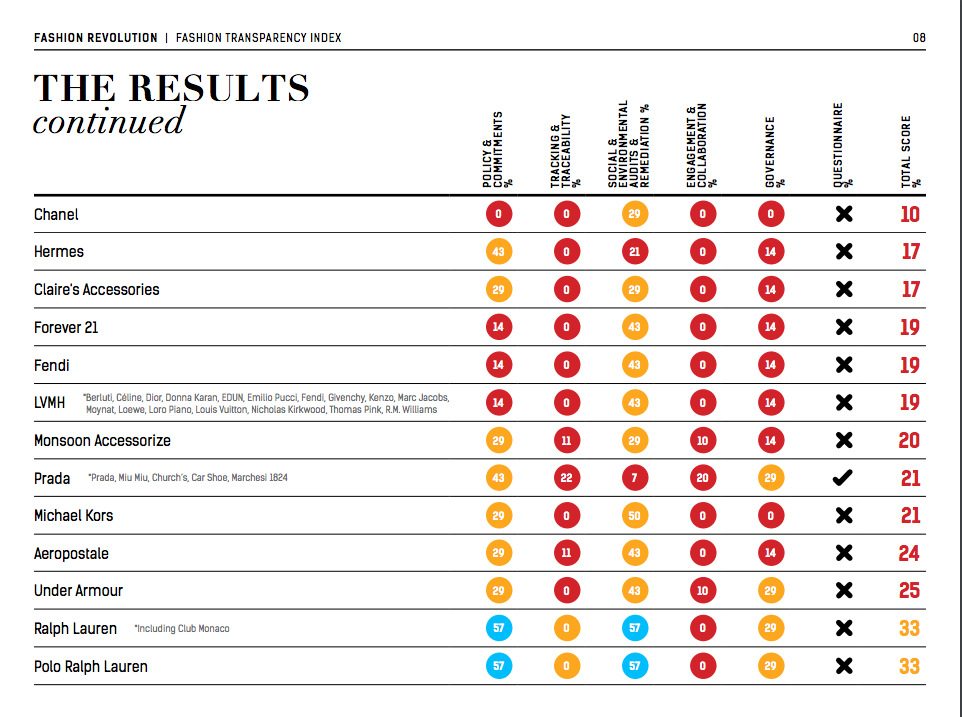

Fashion Revolution’s Fashion Transparency Index 2018 which reviews and ranks 150 major global brands and retailers according to their social and environmental policies, practices and impacts, throws a spotlight on how brands and retailers are tackling gender-based discrimination and violence in supply chains. The report specifically looks at how they are supporting gender equality and promoting female empowerment, both in their own company and in the supply chain.

Whilst, most brands publish policies on discrimination, harassment and abuse, the research show that only 37% of brands are publishing human rights goals. Without reporting on goals and, importantly, annual progress towards these goals, consumers have no way of knowing whether their clothing purchases are really helping to drive improvements for the women who are making their clothes.

Only 40% of brands and retailers reported on capacity building projects in the supply chain that are focused on gender equality or female empowerment, while just 13% publish detailed supplier guidance on issues facing female workers in their Supplier Codes of Conduct. Only 37 out of the 150 brands surveyed report signing up to the Women’s Empowerment Principles, an initiative by the United Nations Entity for Gender Equality, or publishing the company’s overall strategy and quantitative goals to advance women’s empowerment.

Meanwhile, just 5% of brands are disclosing any data on the prevalence of gender-based labour violations in supplier facilities, such as sexual harassment and other forms of gender-based violence, or the treatment and firing of pregnant workers.

Five years after the Rana Plaza collapse, women in Bangladesh are certainly working in safer conditions as a result of factory inspections and remediation, but little to nothing has been done to make them safer from harassment, violence and abuse. Brands need to do more than sell empowering T-shirts. They need to make sure their policies are put into practice, and not just in the visible places during fashion shoots or within their company, but also in their supply chains. The people making our clothes may not be visible, but every garment they make has a silent #MeToo woven into its seams.

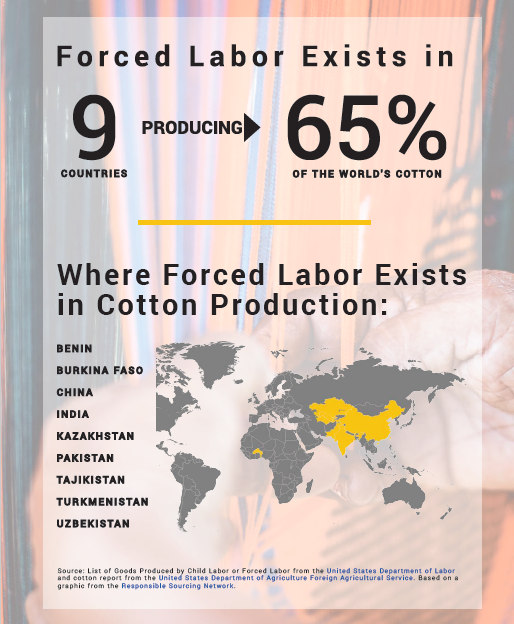

KnowTheChain have launched a ranking of 20 large clothing and footwear companies on their efforts to eradicate forced labor and human trafficking from their supply chains. Their Apparel & Footwear Benchmark Findings Report found only a small group of companies seriously addresses exploitation. Most companies have systems in place to monitor and react to forced labour and human trafficking, but few companies address systemic causes.

The four highest performing companies (Adidas, Gap, H&M and Lululemon) achieve scores above 60/100. Among the lowest performing companies are Hong Kong-based Belle International Holdings (0/100), Chinese clothing manufacturer Shenzhou International Group Holdings (1/100), and the luxury Italian fashion house, Prada (9/100). Across seven measurement areas, the average company score is 46 out of a possible 100. Overall, luxury brands including Hugo Boss, Kering (holding company of Alexander McQueen, Gucci, Stella McCartney and others) and Ralph Lauren score much lower than high street apparel retailers (such as H&M, Inditex or Primark), with none achieving an above average score.

This echoes the findings of Fashion Revolution’s Fashion Transparency Index, published in April 2016, where Prada, Ralph Lauren and other luxury companies received some of the lowest scores.

Longstanding public awareness and pressure, spurred from incidents of child labour in the footwear sector in the 1990s and grave health and safety incidents in Bangladeshi factories in recent years, has resulted in companies putting in place supply chain monitoring systems. However, these have a strong focus on first tier suppliers, while workers tend to be at the greatest risk further down the supply chain. Adidas, which ranked highest in the benchmark (81 out of 100 points), works in partnership with its first tier suppliers to support training for second tier suppliers and subcontractors, as well as develops models to address risks of forced labour in its third tier supply chain.

Forced labour in this sector occurs both at the raw materials level and during the manufacturing stages of apparel and footwear companies’ supply chains. The report finds that all companies benchmarked can improve in rolling out programmes that reach to all tiers of their supply chains. Companies are encouraged to promote direct hiring of workers where possible as well as to perform robust due diligence of third-party recruitment agencies. Companies are also encouraged to engage directly with supply chain workers outside the factory context, allowing companies to get a clearer picture of what is happening on the ground.

“Despite international and brand attention on worker issues for more than twenty years, many retailers haven’t addressed the deep seeded causes of worker abuse in their supply chains. Hopefully this benchmark will help them recognise that they need to do better by the people making their clothes and shoes,” said Killian Moote, director of KnowTheChain.

We can all put pressure on brands to address forced labour and other issues by asking the question #whomademyclothes as transparency is an essential first step towards improving conditions in the supply chain. Use the pledge at the bottom of Fashion Revolution’s home page to send a tweet to your favourite brand.